Abstract

We aimed to identify the critical insights from empirical peer-reviewed studies on online romance fraud published between 2000 and 2021 through a systematic literature review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol. The corpus of studies that met our inclusion criteria comprised twenty-six studies employing qualitative (n = 13), quantitative (n = 11), and mixed (n = 2) methods. Most studies focused on victims, with eight focusing on offenders and fewer investigating public perspectives. All the victim-focused studies relied on data from the Global North, except for Malaysia. Five offender-focused studies used online data available in the public domain, and three derived their data from West Africa. Our review highlights offenders' techniques to deceive and manipulate victims, as revealed in these studies, and highlights some limitations of offender- and victim-focused studies. The dominant framework used across the studies was found to be the “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model.” While this framework provides a helpful way of considering the stages of victim involvement, it also faces some limitations, which we highlight. Our study reviews the current state of empirical knowledge on romance fraud and identifies certain gaps and biases in the literature. We argue there is a need for further research into online romance fraud to enhance our understanding of it both from the perspective of the offender as well as the experience of the victim. We also highlight the need for a more inclusive and greater range of regional and global diverse range of data sources and perspectives. Given the scale and impact of online romance fraud, we conclude that its study would benefit from a richer empirical engagement that recognizes it as both a regional and global phenomenon.

1. Introduction

I am lost and alone. “I have recently separated from my husband and, at 51, find myself in unfamiliar dating territory that bears no resemblance to the courting rituals of my twenties and thirties (Times, 2019).

The impact of technology-mediated communication on social interaction has been widely felt, and perhaps nowhere so much as in our dating habits and preferences. Romantic connections are increasingly being forged within online contexts rather than through personal connections (Dibble and McDaniel, 2021, Kwok and Wescott, 2020, Wiederhold, 2020), with the value of the online dating market standing at approximately $7.5 billion in 2021 (Grand View Research, 2021). In 2020, approximately 23% of individuals residing in the United States reported engaging in a romantic encounter with an individual they initially met through a dating website or application (Pew Research Center, 2020). Similarly, in the UK, 15% of citizens aged between 25 and 45 were estimated to be using online dating apps (Statista, 2021).

The shift towards online dating has stimulated attempts to exploit the public’s changing habits for criminal economic gain. Romantic deception for financial gain notably pre-dates the internet, for example, in the case of the 16th century so-called ‘Spanish prisoner scams’ (Gillespie, 2017, p.218). The subsequent expansion of online dating from around the end of the late 20th century and the increasing sophistication in fraudulent applications of technology more generally have, however, hugely increased their potential reach and ease of implementation. However, online romance fraud is distinct from other types of online fraud because the perpetrator intentionally tries to create an emotional connection or sense of dependence between themselves and the victim (Lazarus et al., 2022, Whitty, 2013a). ‘Online romance fraud’ as this type of offense is known, involves a situation where;

…scammers …use the development of love affairs as a toolbox to lure their victims into offering money to them. For scammers, it does not matter if the owner of the money is a man or woman; scammers consider victims to be ‘good clients’ inasmuch as they can steal funds from them without much ado. [Therefore] romance scams can be defined as the deployment of fake romantic relationships primarily for material ends (Lazarus, Button and Kapend, 2022, p.387).

The material rewards from online romance fraud for offenders can be substantial and have grown significantly in recent years. According to the US Federal Trade Commission, the losses incurred in 2021 amounted to more than $547 million, over six times the amount lost in 2017 (Fletcher, 2021). Notably, this figure represents an almost 80% rise compared to the losses incurred in 2020 (Fletcher, 2021). However, despite these spiraling losses merged with their psychological damage to victims, research into the practice has been somewhat limited. We, therefore, lack a detailed understanding of this type of fraud. In particular, we lack a clear overview of the extent of research into online romance fraud that has taken place and its key insights. That is the aim of this article.

We have systematically reviewed literature from the past two decades to identify the state of current knowledge about online romance fraud. No review on the topic exists, except for Coluccia et al.'s (2020) work, which primarily delves into the epidemiological and pathological aspects of the subject matter, summarizing findings from a set of twelve studies. Our focus and scope are different. We aim to sharpen the sociological eye on the topic through a systematic review. Systematic reviews go beyond traditional literature reviews to encompass systematic, structured, and explicitly described steps of gathering and analyzing relevant existing knowledge (Harris et al., 2014, Knobloch et al., 2011, Moher et al., 2009, Pollock and Berge, 2018).

In scrutinizing the type of empirical data and sources behind claims about online romance fraud, we concur with Harris et al. (2014) in recognizing that the caliber of empirical studies used in a systematic review shapes the quality and strength of recommendations derived from it. We recognize that online fraud comes in many forms (Ibrahim, 2016, Junger et al., 2023, Whittaker and Button, 2020). In our article, however, we conduct a systematic review to determine the extent to which empirical research supports broad assertions about online romance fraud in particular.The overall aims of this review are twofold: to better understand what existing empirical research into online romance fraud tells us. For example, does it offer unambiguous findings on perpetration methods or offender and victim type? And second, to analyze whether the online romance fraud literature shows any specific gaps or potential biases. For example, does the existing literature engage with offenders and their offending cultures, worldviews, and ideologies from various regions worldwide?

2. Method

2.1. Approach

Systematic reviews play an essential role in social research. Not only can they help in synthesizing current knowledge in a given field, but they can also identify problems within primary research that better shapes how future studies are conducted. By bringing together the attempt to address multiple questions that may be hard to answer within individual studies, they can also assist in generating more developed theoretical frameworks, or highlight limitations in prevailing ones. Such reviews are not without their limitations, however, in that the process that makes them rigorous and transparent may in the process leave out valuable insights that fall out of scope. In order to make a systematic review useful for its audience, it must be carefully crafted to meet specific standards. For the review to be effective, the purpose must be stated clearly and accurately; how it was conducted (in particular, the eligibility inclusion criteria for studies, how they were reviewed and selected, and the coverage limits); and a statement of what was found (Page et al., 2021).

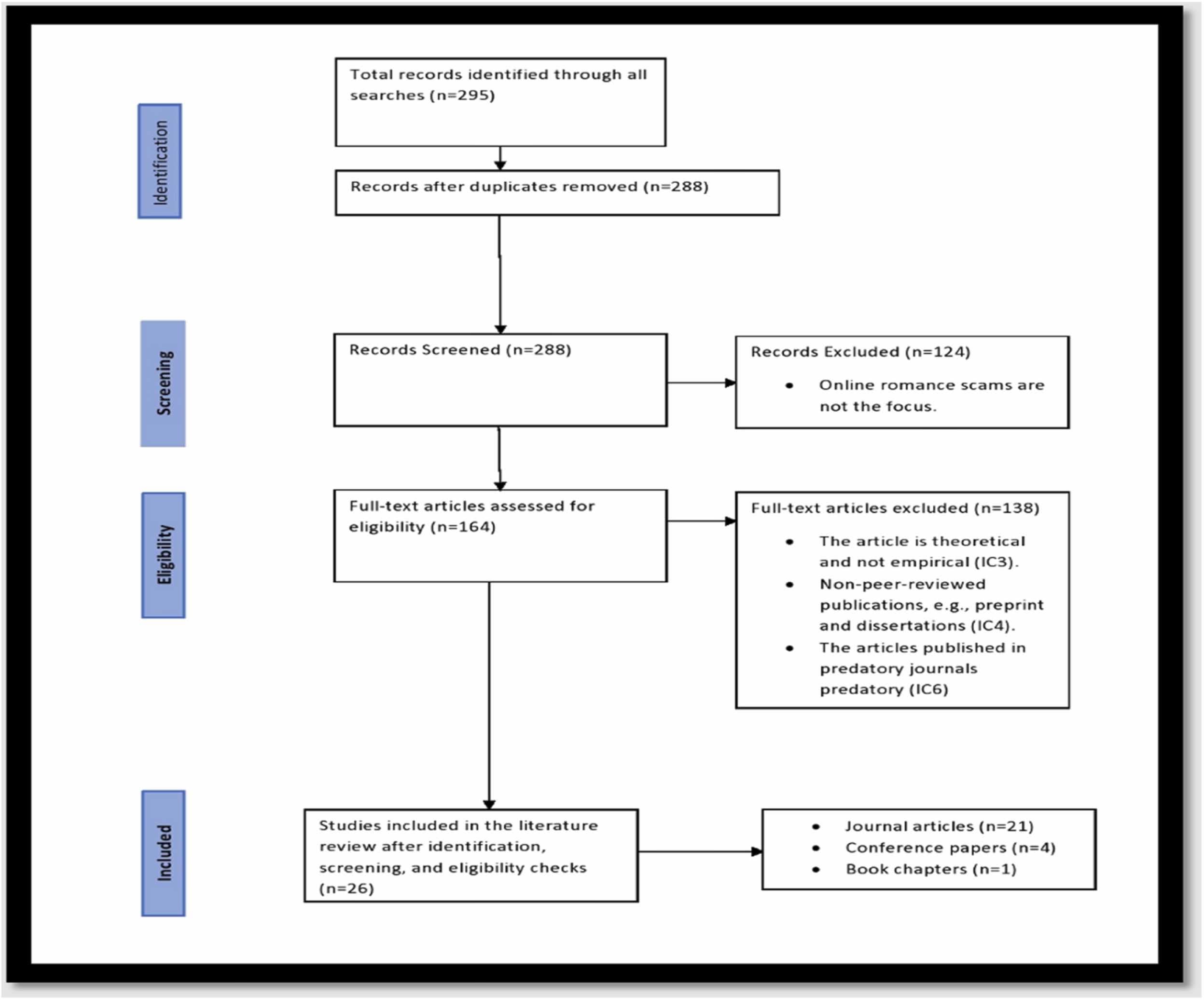

Systematic reviews can be undermined by a lack of transparency in the selection methods and a failure to explain what the selected studies imply, including evaluating their quality and the import of their findings. To ensure the robustness of the review, this study drew upon the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Bedenlier et al., 2020, Knobloch et al., 2011, Moher et al., 2009, Page et al., 2021, Page et al., 2022). Specifically, this study benefited from “the PRISMA 2020” guidelines, "which are applicable for mixed-methods systematic reviews that encompass both quantitative and qualitative studies" (Page et al., 2021, p.3). An advantage of using PRISMA is that it provides an evidence-based set of recommendations for more effective reporting of systematic reviews. PRISMA consists of a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow process centered upon the following stages (Bedenlier et al., 2020; Knobloch et al., 2011; Moher et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021):

Identification

Screening

Eligibility

Inclusion

Taken together, these are designed to ensure effective inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies selected within any review.

The inclusion criteria are shown in Table 1 below. First (IC1), we restricted our study to sources that were available online. This meant that any works not published in an online form were excluded. Second (IC2), we restricted the language of publication to English. Therefore, all works not published in English were excluded because the research team was not competent in other languages. Third (IC3), given the nature of the review, all the included studies had to be based on original empirical research: qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods. Fourth (IC4), while all empirical studies on online romance fraud included in this review were peer-reviewed publication outputs (e.g., book chapters and journal articles), we excluded dissertations and preprint papers. Fifth, we restricted our search to those published between 2000 and 2021 (IC5). Sixth, we also used quality criteria to assess the quality of the studies, e.g., to exclude studies published in predatory journals (IC6). Finally, all included studies had to be relevant to our topic of interest, as captured by our choice of search terms (IC7).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

Publications available online (IC1) | Publications unavailable online |

Publications in English language (IC2) | Publications not in English language |

Empirical research output except for preprints and dissertations (IC3) | Non-empirical research outputs, e.g., conceptual papers |

Peer-reviewed publications, e.g., journal article (IC4) | Non-peer-reviewed publications, e.g., preprint and dissertations |

Publications 2000-2021 (IC5) | Publications before 2000 |

Publications in non-predatory journals (IC6) | Publications in predatory journals |

Online Romance fraud-specific outputs, e.g., exemplified in their titles, keywords, abstracts (IC7) | Non-online romance fraud-specific outputs |

We chose to restrict our review to the period 2000–2021 because this coincided with the advent and subsequent growth of widely commercialized dating sites and apps (e.g., Tinder) and with the internet boom in many parts of the world, particularly in clusters where online romance frauds are often attributed to such as West Africa, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. Though the broad concept of ‘romance fraud,’ ‘fraud’ or ‘scams’ in general precedes the advent of internet technology (Gillespie, 2017, Lazarus, 2019), articles that focus on terrestrial offending in the context of romance (e.g., defrauding a spouse) are beyond the scope of this study. Instead, the focus here is on the new (digital) means of forming relationships, which have inevitably increased the opportunities for offending by allowing fraudsters and their victims to interact more easily and across greater geographical distances, as well as making the subterfuges easier, e.g., through profiles that bear no correspondence to the appearance, characteristics or even sex of the offender.

2.2. Information sources & article selection

Online romance fraud studies have been published in various forms (e.g., conference papers, journal articles, dissertations, books, and book chapters). Thus, we searched a range of sources such as Web of Science, Psych Info, IEEE Digital Library, SAGE, Wiley, and ScienceDirect, using commonly applied keywords relevant to online romance fraud that have been previously applied to the lexis of the fraud. For example, "romance scam," "sweetheart swindle," "romance fraud," "romance scammer," "dating scam," "love scam," and "romance fraudsters." The decision to include the word "romance," "love," "dating," or "sweetheart" was intentional to enable us to exclude studies on other forms of online scams or frauds. Although the terms scam and fraud are often used interchangeably in existing studies, we acknowledge that they should actually be treated as separate terms. In line with the argument that scams and frauds are distinct concepts, we will henceforth use the term "fraud" instead of "scam" unless explicitly citing another author's use of the term or the name of a specific theory. This strategy highlights the severity of criminal actions rather than risk trivializing them.

2.3. The data collection process

Two team members independently assessed the studies which met our inclusion criteria to extract the information relevant to our research aims. We first classified the studies according to their essential features – as outlined in Table 2 below. We then aimed to identify the study details that would enable us to draw conclusions about their findings and the state of research in this field (cf. (Bada and Nurse, 2021, Knobloch et al., 2011, Lopes et al., 2022; Moher et al., 2009), as also presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive and In-depth classification of the studies.

Levels | Variables |

Classification of studies: key features | [a] Publication year. [b] Publication venue (e.g., name of conference or journal). [c] Methods or approaches (e.g., quantitative survey, qualitative interview, or mixed methods) [d] Respondents (e.g., victims, perpetrators, law enforcers). [e] Location of participants/study [f] Size of data (e.g., n = 101). [g] Publication type (e.g., book chapter, conference paper, journal article). [h] Affiliations of authors, the geographical location of the affiliations |

Identification of key findings from studies | [a] Favored theoretical perspective and limitations. [b] Themes from offender-focussed studies, motives for romance fraud and limitations [c] Themes from victim-focussed studies, and limitations [d] Financial and psychological impact. [e] The meaning and uniqueness of romance fraud perpetration methods and fraudsters’ justifications. |

3. Results

3.1. Selection of articles

We initially found 295 publications from the following databases: Web of Science, Psych Info, IEEE Digital Library, SAGE, Wiley, Scholastica, and ScienceDirect. We eliminated duplicates, after which we were left with 288 articles. Based on the title, abstract, keywords, introduction, and conclusion, we then sought to remove any publications that were not, in fact, concerned with online romance fraud, which resulted in 124 articles being removed from the data (as shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow Chart of the Selection Process.Based on the title and abstract, we then checked against our inclusion criteria to ensure that all four were satisfied. No publications were removed following the application of IC1 and IC2. However, a further 116 outputs were discarded after IC3 was applied based on the absence, presence, and content of the method section. IC3 warrants that all publication outputs included in this review were based on primary qualitative and quantitative data sets. In turn, we removed eighteen publications that did not meet IC4. After this process, we re-examined the data by closely reading the methods sections of the remaining publications. No publications were removed following this check. We also used quality criteria to exclude studies published in predatory journals. Upon closer examination, we discovered that four studies were published in a predatory journal and therefore did not meet the quality criteria (1C6), so they were excluded. As a result, twenty-six empirical studies were identified for inclusion in this systematic review.

3.2. Article characteristics

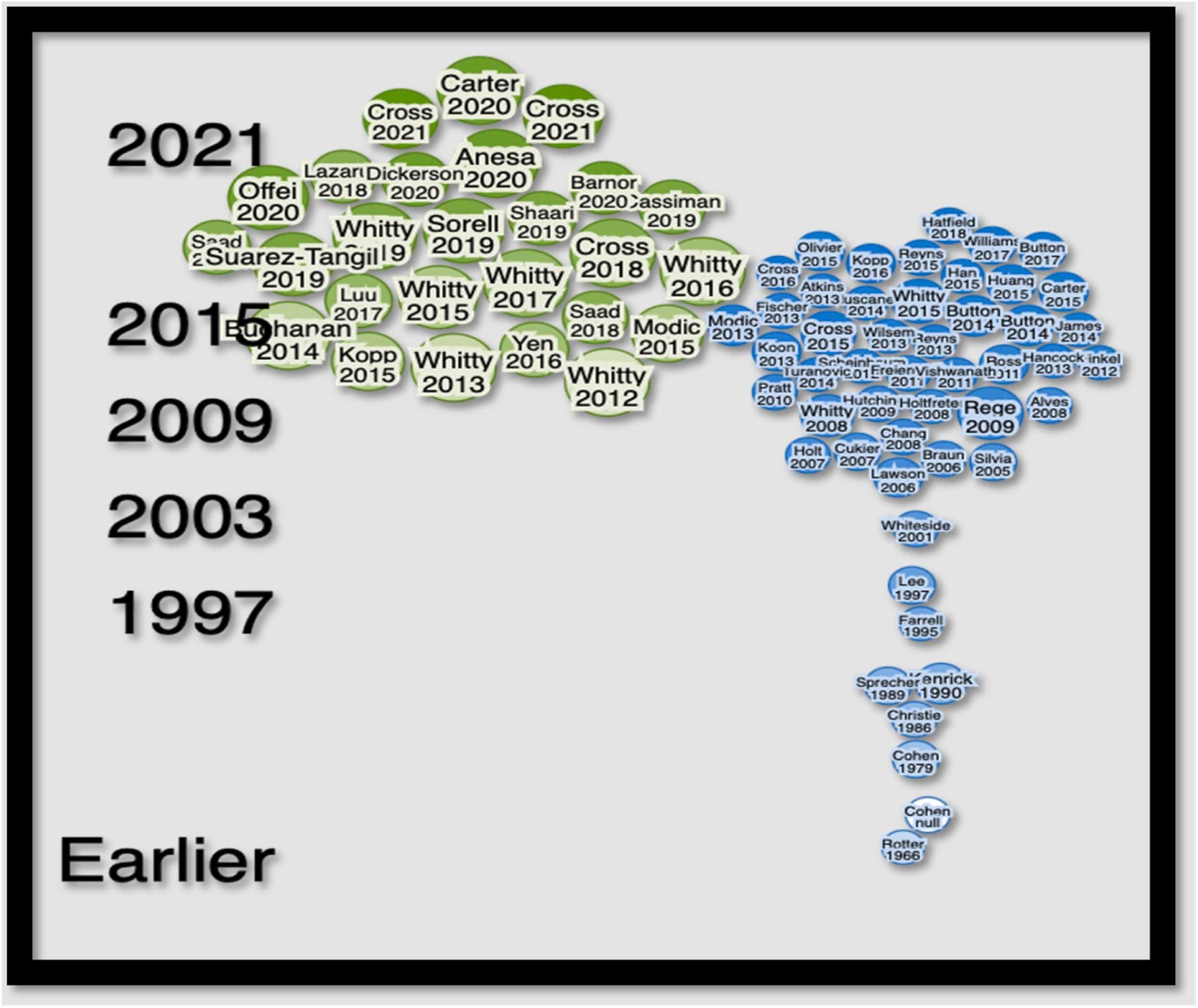

Fig. 2 displays empirical studies that examined online romance fraud published between 2012 and 2021. The green dots depict twenty-six empirical studies we included, while the blue dots represent the excluded ones. The arrangement of both green and blue dots in chronological order visually represents the timeline of the research conducted on this topic.

Fig. 2. Visual representation of studies.

Of the 26 publications identified, twenty-one were journal articles, one was a book chapter, and four were (peer-reviewed) conference papers. The 26 outputs involved 46 authors. One author, Whitty, appeared in nine of the twenty-six publications as co-author (five outputs) and sole author (four outputs). Two authors – Buchanan and Cross, were involved in three publications, co-authoring with others. Except for Abdullah and Saadi, who featured in two collaborative studies, the remaining authors featured in only one publication each, in four cases as sole authors. The authors' affiliations were based in only seven countries, with some uneven locations – possibly due to our inclusion criteria, which only covered English language publications and favored those countries with online repositories. The affiliation of the authors was as follows: the United Kingdom (11), Australia (9), the United States (5), Malaysia (3), Italy (1), Belgium (1), and Ghana (1). It is important to note, though, that this analysis is based on the professional affiliations of the authors rather than their countries of origin or nationalities. Consistent with this geographical bias, all studies focusing on the victims used data from the Global North, except for Malaysia, e.g., Shaari et al.’s (2019) study of victims of fraud in Malaysia.

3.3. Research approaches and data sources

Half the studies drew on qualitative approaches (13 studies), with a smaller number of quantitative (11 studies) and mixed methods (2 studies) approaches. The nature of the data varied across the studies. Some studies relied on online data sources available in the public domain, namely fake dating profiles (Kopp et al., 2015), offenders’ messages (Anesa, 2020), music lyrics (Lazarus, 2018), and suspected romance fraud adverts (Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). Another group of studies recruited participants directly for their qualitative (e.g., Barnor et al., 2020, Cross et al., 2018) and quantititave studies (e.g., Offei et al., 2020, Saad and Abdullah, 2018). Interestingly and innovatively, one qualitative study was based on a single online romance fraud case (Carter, 2020). All twenty-six studies we identified utilized varying data sources except for four studies (Saad and Abdullah, 2018, Saad et al., 2018, Whitty, 2013b, Whitty and Buchanan, 2016). Specifically, two qualitative studies (Whitty, 2013b; Whitty and Buchanan, 2016) used the same data, as did two quantitative studies (Saad and Abdullah, 2018, Saad et al., 2018). In this latter case, the two studies (i.e., Saad and Abdullah, 2018; Saad et al., 2018) were substantively similar, with one being a conference paper and the other being a journal article. However, we included both of them because the methods of analysis they used differed.

3.4. Focus of studies and methodological diversity

Among the fifteen studies focused on victims, the methods comprised eight qualitative, six quantitative, and one mixed method study. Eight studies focused on offenders (Anesa, 2020, Barnor et al., 2020, Cassiman, 2019, Kopp et al., 2015, Lazarus, 2018, Offei et al., 2020, Suarez-Tangil et al., 2019, Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). Of these, three studies conducted in Ghana involved interviews (Barnor et al., 2020), ethnographic work (Cassiman, 2019), and quantitative questionnaires (Offei et al., 2020). Five other offender studies used data available in the public domain (Anesa, 2020, Kopp et al., 2015, Lazarus, 2018, Suarez-Tangil et al., 2019, Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). The remaining three studies covered the general population, comprising two quantitative studies (Luu et al., 2017, Whitty, 2018) and one mixed-method study (Dickerson et al., 2020). Nineteen contributions were disseminated across nineteen distinct outlets. An additional three articles were featured in the "British Journal of Criminology" (Carter, 2020, Cross et al., 2018; Whitty, 2013b). Two articles each were in "Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking" (Whitty, 2018, Whitty and Buchanan, 2012) and "Security Journal" (Whitty, 2013a; Sorrel and Whitty, 2019). Again, our decision to exclude articles written in languages other than English may have influenced the publication outlets of the sample.

3.5. Theoretical frameworks and an inconsistency gap

While some of the twenty-six online romance fraud studies anchored directly on theories of crime, e.g., Barnor et al. (2020), Lazarus, (2018), and Saad et al. (2018), not all did (e.g., Kopp et al., 2015, Modic and Anderson, 2015). This suggests the lack of an effective “blueprint,” which Grant and Osanloo (2014) have argued should be a measure of evaluation of studies. Of those studies which did offer a theoretical background, some victim-focused studies explicitly favored the scammers’ persuasive technique theory (Cross et al., 2018, Shaari et al., 2019, Whitty, 2019), while others drew upon established crime theories such as the routine activity theory (e.g., Saad and Abdullah, 2018), the neutralization technique theory (e.g., Offei et al., 2020), and the moral disengagementmechanisms (e.g., Lazarus, 2018).Table 3 provides an overview of the 26 works, including key characteristics such as the approaches used, sample sizes employed, key findings, research questions, whether the studies focused on victims or offenders, as well as the institutional affiliation of the author(s).Table 3. Characteristics of the 26 empirical studies.

Year | Title of Article | Type of Outlet | Name of Outlet | Methodological Approach | Data Source | Size of Data (n = ) | Name of Authors | Affiliations of Authors | Geographical Affiliations | *Explicit and * *Implicit Research Questions | Findings |

2012 | The Online Romance Scam: A Serious Cybercrime | Journal Article | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | Quantitative | Victims | 2028 | Monica Whitty; Tom Buchanan | University of Leicester; University of Westminster | United Kingdom | * *To learn about the prevalence of online romance scams in Great Britain, how widely the crime is known, and how individuals are learning about it. | This research provides some descriptive statistics about knowledge of romance scams and its victimisation in the UK. Despite, at the time of publication, the scam being relatively new the authors suggest that an estimated 230,000 British citizens may have fallen victim to this crime. |

2013 | THE SCAMMERS PERSUASIVE TECHNIQUES MODEL: Development of a Stage Model to Explain the Online Dating Romance Scam | Journal Article | British Journal of Criminology | Qualitative | Victims | 20 | Monica Whitty | University of Leicester | United Kingdom | *To examine the persuasive techniques that scammers employ and consider whether previous theories on persuasion are adequate in explaining why victims are conned by this particular fraud. | The author finds that the elaboration likelihood model needs to adequately explain the scam. The near-win phenomenon provides a useful explanation for why some individuals remain in the scam. In addition, the author develops a new model called the “Scammer Persuasive Technique Model” to understand how the scam progresses, which seeks to explain why individuals get sucked into the scam and the carefully orchestrated steps that offenders take to defraud their victims. |

2014 | The online dating romance scam: causes and consequences of victimhood | Journal Article | Psychology, Crime, & Law | Quantitative | Victims - Online daters, Victim Support website | Study 1–85; Study 2–397 | Tom Buchanan; Monica Whitty | University of Westminster; University of Leicester | United Kingdom | *To examine why some individuals are willing to give up their personal savings for someone they have met online. | The work provides a novel insight into the characteristics and experiences of people affected by romance scams. A single psychological variable is associated with susceptibility to victimization in romance scams; the romantic belief of idealization. In addition, less emotionally stable males may be affected by fraud on an emotional level. |

2015 | The Role of Love stories in Romance Scams: A Qualitative Analysis of Fraudulent Profiles | Journal Article | International Journal of Cyber Criminology | Qualitative | Offenders -Fake dating profiles | 37 | Christian Kopp; Robert Layton; Jim Sillitoe; Iqbal Gondal | Federation University | Australia | * *To provide a qualitative analysis of fake online dating profiles | Fraudulent dating profiles are identified as following typical characteristics. The authors conclude that each profile analyzed in their study utilizes personal stories suited explicitly for the scam. They are typically detailed enough to “hook” the victim but leave enough ambiguity, which can be adapted in the “grooming” phase of the scam. As such, the authors suggest that once the scammer learns more about the victim, the story presented in the profile can be replaced with a better-matching story. |

2015 | Anatomy of the online dating romance scam | Journal Article | Security Journal | Qualitative | Victims - Posts on a public website, victims of fraud, SOCA officer | Study 1 – 100 Study 2–20 Study 3 – 1 | Monica Whitty | University of Leicester | United Kingdom | * *To outline the anatomy of romance scams | The model presented in this paper outlines the anatomy of a typical romance scam that encompasses five distinctive phases. In the first stage, an offender creates an attractive dating profile. In the second stage, the offender grooms the victim in preparation for the third stage. In the third stage, the offender requests money from the victim. In stage four, victims are sexually humiliated by the offender. Lastly, in stage five, the victim realizes they have been scammed. |

2015 | The online dating romance scam: The psychological impact on victims – both financial and non-financial | Journal Article | Criminology & Criminal Justice | Qualitative | Victims | 20 | Monica Whitty; Tom Buchanan | University of Leicester; University of Westminster | United Kingdom | *To learn about the impact this crime has on individuals. | The authors find that “victims” of romance scams are not only those that have lost money, but also those that have not lost money. The argument here is that both those had lost money and those that did not reported the same psychological impact. Furthermore, the authors find that in the case of those victims that did lose money, they experienced a “double hit” from both the monetary loss amount lost and the psychological impact. |

2015 | It's All Over but the Crying: The Emotional and Financial Impact of Internet Fraud | Journal Article | IEEE Security & Privacy | Quantitative | Victim perspectives | 6609 | David Modic; Ross Anderson | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | *To examine the emotional costs of victims. | The authors find that romance scams, from a broad range of frauds, have the highest emotional impact for victims. The authors also identify that offenders utilising advance-fee fraud modalities also seek to build a trusted relationship with potential victims, making the inevitable betrayal similar to romance scams. |

2016 | Case Study: Romance Scams | Book chapter | Understanding Social Engineering Based Scams | Quantitative | Offenders - Suspected romance scam adverts | N/A | Markus Jakobsson | Agari | USA | * *To describe romance scams and to perform an experiment to establish metrics around it | The authors, by using magnetic honeypot adverts posted to the Craigslist M4W category in the 100 “slowest” US cities, find that 58% of the responses received were traditional romance scams. They also find that affiliate marketing scams (20%) was a common type of scam in the responses to their advert. Lastly, the authors find that around 2% of the scammers will click on links in the authors responses, and that 5% will reply. |

2017 | Safeguarding Against Romance Scams – Using Protection Motivation Theory | Conference Proceedings | 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) | Quantitative | Public | 399 | Veronica Luu; Lesley Land; Wynne Chin | University of New South Wales; University of Houston | Australia; USA | *How do threat appraisals impact users’ intention to adopt protection mechanisms when using OD websites? How do coping appraisals impact users' intention to adopt protection mechanisms when using OD websites? | The authors examined the factors and processes leading to adoption intention of protection mechanisms in the broad domain of online dating. The findings from this study illustrate that the coping appraisal process, an individual’s assessment of their ability to use a protection mechanism and their confidence that it will be successful, generally has a greater impact on adoption intention than the evaluation of the threat. Attitude, the author’s identify was deemed to be a considerable influencer of adoption intervention, functioning as a mediator. |

2018 | Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims | Journal Article | Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | Quantitative | Victim perspectives | 11,780 | Monica Whitty | University of Melbourne | Australia | * *To report the psychological characteristics of romance scam victims | This study examined whether individual characteristics could predict whether somebody can become a romance scam victim by comparing victims with non-victims. The hypotheses was tested using standard forced entry binary logistic regression, with victimisation being the outcome variable. The author concludes that the model introduced in the study was statistically significant in predicting victimisation. Two of the findings, however, were in the opposite direction to what was predicted. |

2018 | Cyber Romance Scam Victimization Analysis using Routine Activity Theory Versus Apriori Algorithm | Journal Article | (IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, | Quantitative | Victims | 280 | Mohd Ezri Saad; Siti Norul Huda Sheikh Abdullah; Mohd Zamri Murah | Royal Malaysia Police; Center for Cyber Security Faculty of Information Science and Technology Bangi | Malaysia | *Is age influencing the tendency to become a victim of cyber romance crime? Is education level influencing the tendency to become a victim of cyber romance crime? Is marital status influencing the tendency to become a victim of cyber romance crime? Is monthly income influencing the tendency to become a victim of cyber romance crime? Is levels of cybercrime awareness influencing the tendency to become a victim of cyber romance crime? | This study finds that those Malaysians in the study aged between 25 and 45 were more likely to become romance scam victims. Furthermore, the authors find that most victims were educated, having either a degree or diploma and that both single and married people can become a romance scam victim. In addition, participants in employment and those considered to lack computer skills online fraud awareness were found to be more susceptible to romance fraud victimisation. Lastly, the authors argue that their study confirms the fundamental principle of RAT theory and its application to cybercrime research. |

2018 | Understanding romance fraud: Insights from domestic violence research | Journal Article | British Journal of Criminology | Qualitative | Victims | 21 | Cassandra Cross; Molly Dragiewicz; Kelly Richards | Queensland University of Technology | Australia | * *To illustrate the techniques that offenders use to ensure victim compliance with their ongoing demands for money | Using Tolman et al.’s (2009) typology of psychological mistreatment, the authors find evidence of eight of the nine types of abuse within romance fraud victims’ narratives. Victims within the authors sample reported economic abuse, isolation, monopolisation, degradation, psychological destabilisation, emotional or interpersonal withdrawal, and contingent expressions of love. As such, by looking at romance fraud through the lens of psychological mistreatment, they demonstrate that there is an overlap between domestic violence and romance fraud in terms of the types of psychological mistreatment. |

2018 | Victimization Analysis Based On Routine Activitiy Theory for Cyber-Love Scam in Malaysia | Conference Proceedings | PROCEEDINGS OF THE 2018 CYBER RESILIENCE CONFERENCE (CRC) | Quantitative | Victims | 280 | Mohd Ezri Saad; Siti Norul Huda Sheikh Abdullah | Royal Malaysia Police | Malaysia | * *To investigate the tendency factors that influence a victim’s susceptibility to romance fraud victimization | This study finds that those Malaysians in the study aged between 25 and 45 were more likely to become romance scam victims. Furthermore, the authors find that the majority of victims were educated, having either a degree or diploma and that both single and married people can become a romance scam victim. In addition, participants in employment and those considered to lack computer skills online fraud awareness were found to be more susceptible to romance fraud victimisation. Lastly, the authors argue that their study confirms the fundamental principle of RAT theory and its application to cybercrime research. |

2018 | Birds of a Feather Flock Together: The Nigerian Cyber Fraudsters (Yahoo Boys) and Hip Hop Artists | Journal Article | Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society | Qualitative | Offenders - Music lyrics in Public domain | 18 | Suleman Lazarus | Independent Researcher | United Kingdom | *What are the ethics of Nigerian cyber-criminals as expressed by music artists? Which techniques do artists deploy to describe their views on cyber-criminals? What might the justifications say about the motives for “cybercrime”? | The author finds that cybercriminals embody a powerful range of psychological mechanisms for disengaging moral control. Furthermore, the author argues that the oratory messages of hip-hop songs that legitimise the activities of cybercriminals may attract more followers that questioners, especially in the case of young people, thereby glamourising and normalising offending behaviour. |

2019 | Online romance scams and victimhood | Journal Article | Security Journal | Qualitative | Victims | 20 | Tom Sorrell; Monica Whitty | University of Warwick; University of Melbourne | United Kingdom; Australia | *Do victims actually share responsibility with the scammer for their losses? | This study argues that romance scam victims are more responsible for their losses the more that they ignore available counter-evidence regarding the legitimacy of the person they perceive themselves as having a relationship with online. Specifically, those that have been scammed a multiple of times or victims of long-term scams may not recognise all of the counter-evidence for what it is, because of the grooming process involved in the scam or through an addiction they develop with being the at the centre of intense romantic attention. Lastly, certain personality types, particularly those with antecedent loneliness and shyness, may not approach online dating profiles sceptically and instead often succumb to intense romantic communication. |

2019 | Online-dating romance scam in Malaysia: An analysis of online conversations between scammers and victims | Journal Article | GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies | Qualitative | Victims | 60 | Azianura Hani Shaari; Mohammad Rahim Kamaluddin; Wan Fariza Paizi; Masnizah Mohd | Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia | Malaysia | *To investigate the persuasive language strategies used as a modus operandi in the online dating romance scam. | The authors identify some common steps and persuasive language techniques used in romance scams, that positive politeness strategies are employed by the offenders initially which is later followed by negative acts towards the end of the relationship when the victims have either come to their senses or decided to end the relationship. The authors find that in the case of Malaysian victims the scammers adapted by using local names for people and places, that although apprehended suspects hold international passports they typically use a Malaysian partner to act in an official capacity, and that finally the use of Muslim names and religious phrases is a common strategy in romance scams targeting Malaysians. |

2019 | Who can spot an online romance scam? | Journal Article | Journal of Financial Crime | Quantitative | Public | 261 | Monica Whitty | University of Melbourne | Australia | *Those who score high on the Romantic Beliefs Scale will be less accurate at detecting fake from genuine profiles. Those who score high on a measure of impulsivity will be less accurate at detecting fake from genuine profiles. Those who score low on Consideration of Future Consequences will be less accurate at detecting fake from genuine profiles. Those who had not spotted a scam will be less accurate at detecting fake from genuine profiles. Those who have a shorter response time will be less accurate at detecting fake from genuine profiles. | The author finds that personality and behaviour predict accuracy in the human detection of romance fraud. Furthermore, belief systems and pre-dispositions can to some extent make them vulnerable to a romance fraud. Participant response times in completing the task was, however, found to be the strongest unique contributor as those that took longer were more likely to distinguish fraudulent profiles from genuine ones. Lastly, those participants that claimed to have spotted a scam prior to the study had better accuracy scores. |

2019 | Spiders on the world wide web: Cyber trickery and gender fraud among youth in an Accra Zongo.

Social Anthropology ,

27 (3), 486–500. | Journal Article | Social Anthropology | Qualitative | Offenders | N/A | Ann Cassiman, | University of Leuven | Belgium | * *To understand the connections between online and offline relationships in ‘Zongos’ in Ghana. To then explore the relationships that young men and women that inhabit these Zongos to understand how they disrupt the existing gender categories and features of marriage, gender roles and relations within Zongo communities. Lastly, to show how the economy of desire leads to the “frauding” of gender and race relations. | The author finds that the line between what is considered an acceptable or unacceptable trick is very thin. Secondly, the interviewees do not fear an increased control and surveillance of their activities because they are already “out there”. Lastly, the article finds that trickery can also generate what the author defines as “creative cultural moments”, that former colonial relations can subsequently be turned upside down in fraud. |

2020 | Lovextortion: Persuasion strategies in romance cybercrime | Journal Article | Discourse, Context & Media | Qualitative | Offenders (messages) | 49 | Patrizia Anesa | University of Bergamo | Italy | * What types of persuasion strategies are employed in online romance scams (ORSs)? How do they differ from other forms of scams? What discursive/linguistic practices can be identified to define models of ORSs? | The author finds that romance scam messages follow similar structural patterns that include processes which aim to arouse interest and build trust which subsequently leads to lapses in the target recipients’ judgements. The messages analysed in the study were found to project an ideal persona which embodies the desires of the recipient. Furthermore, the messages were found to groom the recipient into an emotional dependency on the offender. |

2020 | Rationalizing Online Romance Fraud: In the Eyes of the Offender | Conference Proceedings | AMCIS 2020 PROCEEDINGS | Qualitative | Offenders (Interviews) | 10 | Jonathan Nii Barnor Barnor; Richard Boateng; Emmanuel Awuni Kolog; Anthony Afful-Dadzie | University of Ghana | Ghana | * *To understand the triggers of online romance fraudsters' behaviours | The authors find an interplay of various socioeconomic factors behind the commission of romance fraud from the offenders perspective including: peer recruitment and training, poverty, unemployment, low level of education and low income. Secondly, the authors identify that offenders will depend on affordable and available technologies and network services. The authors also find that a lack of confidence in law enforcement provides ample opportunity for offenders to commit romance fraud. Offenders are found to possess basic computer and social skills which helps them in committing romance fraud. Lastly, offenders find justifications to make sense of their actions. |

2020 | Distort, extort, deceive and exploit: exploring the inner workings of a romance fraud | Journal Article | British Journal of Criminology | Qualitative | Victims | 1 | Elisabeth Carter | University of Roehampton | United Kingdom | * *To understand the grooming strategies used in romance fraud. | The author finds that in contrast to the narrative that victims fall for romance scams because of over-romantic ideations, victims may also employ poor decision-making practices because of the skill of the offender. Underpinning this research is the argument that in the context of romance fraud, responsive techniques that focus on protection and preservation can be used to mask financial requests that may otherwise appear alarming. |

2020 | Automatically Dismantling Online Dating Fraud | Journal Article | IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security | Quantitative | Offenders (fake dating profiles) and random sample of public dating profiles | 20,122 | Guillermo Suarez-Tangil; Matthew Edwards; Claudia Peersman; Gianluca Stringhini; Awais Rashid; Monica Whitty | King's College London; University of Bristol; Boston University; UNSW Cranberra | United Kingdom; USA; Australia | * *To understand the distinctions between scammer profiles and those of regular users on dating platforms. To design three independent classification modules which analyse different aspects of public dating profiles. Lastly, to synthesise the classifiers into an ensemble classification system. | The authors present a system for detecting fraudulent dating profiles. The uniqueness of their system is that it relies on a wide range of features that are difficult to evade, such as the text in the profiles as opposed to IP addresses which forum moderators typically check. The authors acknowledge that this system, however, is not full proof. Their supposition is that scammers could circumnavigate the system by cloning the profiles of legitimate dating users from different websites. |

2020 | How Do Individuals Justify and Rationalize their Criminal Behaviors in Online Romance Fraud? | Journal Article | Information System Frontiers | Quantitative | Offenders ("individuals with knowledge about online romance fraud.") | 320 | Martin Offei; Francis K. Andoh-Baidoo; Emmanuel Wusuhon Yanibo Ayaburi; David Asamoah | University of Texas Rio Grande Valley | USA | *How does neutralization influence the intention to commit online romance fraud? how does denial of risk perception interact with the effect of neutralization on the intention to commit online romance fraud? | The study finds that a denial of victim effect is used by offenders to justify their intention to defraud. It also finds that offenders realise it is difficult to justify that they can claim no responsibility and injury because the victim could demonstrate, where necessary, monetary and psychological losses and that the offender was responsible. |

2020 | Contextualised Cyber Security Awareness Approach for Online Romance Fraud | Conference Proceedings | 7th International Conference on Behavioural and Social Computing (BESC) | Mixed Methods | Public | 12 | Sara Dickerson; Edward Apeh; Gail Ollis | Bournemouth University | United Kingdom | * *To increase user awareness and provide real-time intervention on romance fraud inside of a dating platform. | The authors primary finding is that if advice about a potential romance fraud is given when a user starts their dating process online, it would in-turn benefit the users of dating platforms by reducing the likelihood for fraud to take place. When prompted, 100% of the experimental group stated that they read additional security information available on the dating platform. In the case of the control group, however, 0% viewed other security information. The authors also find that 100% of the respondents from the experimental group claimed to have learnt new information about romance fraud through an awareness message that was sent to them before they filled the questionnaire in. |

2021 | The Use of Military Profiles in Romance Fraud Schemes | Journal Article | Victims & Offenders | Mixed Methods | Victims | 2478 | Cassandra Cross; Thomas Holt | Queensland University of Technology; Michigan State University | Australia; USA | * *To examine the ways in which a military narrative is employed in romance fraud | The authors find that whilst gender was non-significant in who falls for the military modality used by romance fraudsters, there is instead a consistent relationship between loss of banking details and the risk of victimisation. A second finding is that victims who fall into low-income brackets are more likely to experience military romance fraud modalities and report economic loss. |

2021 | "I Suspect That the Pictures Are Stolen": Romance Fraud, Identity Crime, and Responding to Suspicions of Inauthentic Identities | Journal Article | Social Science Computer Review | Qualitative | Victims | 2671 | Cassandra Cross; Rebecca Layt | Queensland University of Technology | Australia | *What actions do individuals take in response to suspicions of inauthentic identities? How can this knowledge be used to improve future prevention messaging? | This article finds that complainants predominantly used an internet search to explore their suspicions, with many in addition also electing to conduct a reverse image search. The results in this study demonstrate the potential effectiveness in this strategy. Secondly, the results also demonstrated the use of fraudulent websites as evidence to support the inauthenticity of a profile. Whilst this was deemed as positive for the complainants, a negative consequence of this was the linking of innocent third parties (who’s identities had been used by offenders in their websites) via digital footprints to fraud through no fault of their own. |

4. Discussion

We now turn to our research questions and address what the studies told us about online romance fraud, gaps, and biases in the literature. In our discussion of offenders, the emphasis on the West African context is due to the sample pattern. All offender-oriented studies relied on online data sources, such as blocklisted dating profiles, fraudulent messages, and advertisements, except for three studies that collected data directly from participants on the ground in West Africa, providing insights through 'real-life' and contextualized testimonies. We discuss insights from offender and victim-oriented studies in turn.

4.1. Offender-focused studies mostly cast their gaze on West Africa

4.1.1. Targeting Westerners

Studies on offenders indicate that cybercriminals often target wealthy Westerners seeking romantic relationships, according to qualitative studies conducted in Ghana (Barnor et al., 2020, Cassiman, 2019). The studies suggest that cybercriminals underestimate the financial harm inflicted on victims from Western countries: they assume that these victims have access to safety nets, such as social welfare and benefits, available in Western societies. This applies to all online fraud victims, not just those who fall victim to online romance fraud. It is a part of the offenders' strategy to circumvent the feeling of guilt: 'the denial of injury' (drawing from the neutralization techniques theory proposed by Sykes and Matza, 1957). Offenders involved in online romance fraud also often participate in various other forms of fraud, such as Advance Fee Fraud (Barnor et al., 2020, Lazarus, 2018), suggesting that the boundaries between the two are not rigid.Even though, from the cybercriminals’ perspectives, Advance Fee Fraud is similar to online romance fraud in terms of its financial returns, romance fraud's effect on victims may differ. Romance fraud involves a level of emotional and sexual connection that is not typically present in other types of fraud and implies, therefore, a greater direct impact on victims. Offenders tend to trivialize the emotional distress experienced by victims of romance fraud as they do to victims' monetary losses. This could be because these offenders see online fraud perpetration as "a game," "hunting," and "not a crime" (Lazarus, 2018, p.70). Understanding the complexities of online romance fraud requires acknowledging the various factors involved, such as the mindsets, beliefs, and worldviews of the perpetrators.

4.1.2. Both men and women are offenders

Despite common assumptions that men predominantly perpetrate online romance fraud, recent literature highlights the significant involvement of women in the perpetration of online romance fraud. Broader discussions on online fraudsters in Nigeria (Lazarus and Okolorie, 2019, Lazarus et al., 2022) and Ghana (Newell, 2021, Warner, 2011) portray men as the main culprits. However, Cassiman's, (2019) anthropological fieldwork in Ghana, specifically on online romance fraud, revealed that offenders have revealed that women play active roles in online romance fraud as perpetrators. Women engage in online romance fraud seeking direct and profitable online contacts without relying on men for mentorship and support. This suggests that women play central roles in the online romance fraud industry, challenging traditional gender roles and stereotypes. This trend further corroborates gender-oriented research such as Krumbiegel et al. (2020), Lazarus et al. (2017), and Forkuor et al. (2020), suggesting a noteworthy shift in West Africa, where women are increasingly embracing career paths that men traditionally dominated. Thus, the role of gender and the implications of the perpetrators' sex for online romance fraud requires further exploration.

4.1.3. Gendered values and societal acceptance

Women who are online romance fraudsters are less socially accepted than men who perform the same activities, according to an ethnographic work conducted in Ghana (Cassiman, 2019). Many people in West African communities see them as transgressing gendered values and appropriate masculine virtues of trickery and disobedience. Society often associates masculinity with assertiveness and cunning, making it more acceptable for men to perpetuate fraud (Cassiman, 2019, Lazarus, 2018). Conversely, femininity is often associated with nurturing and caring, which makes it less acceptable for women to participate in activities such as online romance fraud. Research by Forkuor et al. (2020), Rush and Lazarus (2018), and Krumbiegel et al. (2020) reveals that West Africa still upholds patriarchal values when it comes to women's gender roles, despite some progress in recent years. It is important to conduct further research to understand better the gender cultures and expectations of women who engage in online romance fraud. Gender should be considered as a key theoretical starting point when investigating online crimes (drawing from the feminist epistemology of digital crimes, e.g., Lazarus, 2021, Marganski, 2020, Choi and Merlo, 2021).

4.1.4. The glamorization and social legitimacy of cybercrime

According to studies that discussed Ghanaian fraudsters by Cassiman (2019) and Nigerian fraudsters by Lazarus (2018), the glamorization of wealth plays a significant role in normalizing and legitimizing online romance fraud in West Africa. Fraudsters use displays of wealth, such as luxury cars and houses, to entice and recruit individuals in their local communities who view their wealth with envy and admiration. Rather than being condemned, fraudsters are often seen as resourceful and intelligent, further perpetuating the social legitimacy of their criminal activities (Cassiman, 2019, Lazarus, 2018). Studies within the broader field of online fraud in this region (Ibrahim, 2017, Lazarus et al., 2022) and specific to romance fraud (e.g., Cassiman, 2019, Lazarus, 2018) provide evidence supporting the social legitimacy thesis of cybercrime in West Africa. Recognizing the impact of glamorization and social legitimacy in cybercrime is crucial for identifying and preventing online romance fraud, particularly among vulnerable populations susceptible to such allurements.

4.1.5. Advantageous comparison

Online romance fraudsters often justify their actions by comparing themselves to other criminals, claiming their crimes are less dangerous than traditional crimes like robbery, rape, or murder (Barnor et al., 2020, Lazarus, 2018). They argue that they should not be called criminals and even question whether people who download movies from pirate sites are considered cybercriminals. This defense mechanism helps fraudsters justify their actions and reduce their feelings of guilt or shame. It also serves as a way to manipulate their victims into thinking that the harm caused by online romance fraud is minimal and, therefore, justifiable. Understanding these strategies for detecting and preventing online romance scams is crucial, particularly for vulnerable populations going through major life transitions, such as seniors, widows, widowers, and divorced individuals.

4.1.6. Seductive images and gender swapping

Individuals who commit online romance fraud use different methods based on the gender they pretend to be on their profile. Female profiles often use seductive photographs from the internet or of themselves to entice potential victims (Cassiman, 2019, Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). Female profiles also express their disinterest in money by stating they are the offspring of "a king or tribal leader" (Kopp et al., 2015, p.210). On the other hand, male profiles frequently focus on projecting an "elitist status" and boasting about their extensive travels to cultivate an enticing and glamorous persona (Anesa, 2020, p.4). The virtual world allows them to create fake online profiles and pretend to be someone they are not. The fluidity of the virtual world also enables them to swap genders in their fake online profiles, making it easier to target a broader range of potential victims and avoid detection. This tactic is particularly effective in online romance fraud, where emotional manipulation plays a significant role. Using seductive images and gender-swapping techniques, fraudsters can create the illusion of a romantic relationship with their victims and gain their trust more quickly. This, in turn, makes it more likely that victims will be willing to send money or provide other forms of financial assistance to their supposed ‘partner’. It is logical to suggest that the prevalence of deepfakes would worsen the fluidity of identity in online romance fraud perpetration and manipulation.1

4.1.7. Tailored tactics of fraudsters

Sophisticated online romance fraudsters employ tactics to customize not only their profiles but also messages to suit the characteristics and location of their potential victims (Anesa, 2020, Kopp et al., 2015, Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). They often acquire pre-written scripts for romance fraud from underground forums that are categorized based on the age, ethnicity, and gender of the targets. Unlike other types of fraud, online romance fraud does not rely on a standard script, making it more challenging to detect using traditional storyline-based filtering techniques (Yen and Jakobsson, 2016). Detecting and filtering this type of fraud requires a different approach since fraudsters tailor their pre-written messages to their victims' characteristics.

4.1.8. Colonial legacies

A grasp of colonial legacies is necessary for understanding the contemporary manifestation of online offending, in general, and in West Africa specifically (Lazarus and Button, 2022a, Lazarus and Button, 2022b). Online romance fraud studies highlight that the colonial legacy of extracting resources from the colonies and exploiting local people led some offenders to see defrauding Westerners as a justifiable business, according to three studies conducted in Ghana (Cassiman, 2019, Offei et al., 2020, Barnor et al., 2020). Some West African perpetrators hold the belief that defrauding individuals from Western nations serves as a means of retribution for the historical suffering endured by their ancestors at the hands of Westerners and Arabs during the era of the slave trade, as well as the exploitation and depletion of both human and natural resources. Hence, in some West African countries, online romance fraud is considered a civic virtue. In many cases, online romance fraudsters are respected members of their communities and enjoy a venerated status as skilled tricksters (e.g., Cassiman, 2019; Offei et al., 2020).

4.1.9. Skin color and ‘race'

Fraudsters often present themselves as white individuals, likely due to a preference for lighter skin color among potential victims, which is viewed as a core criterion of desirability (Suarez-Tangil et al., 2019). The preference for lighter skin color may reflect a hierarchy of desirability on specific dating sites, where skin color can be a prerequisite for accepting relationship requests. Thus, a distinctive feature of online romance fraud is that fraudsters do not impersonate, for example, people of African heritage or other groups with dark skin color but situate themselves in predominantly white Western nations and adopt light-skinned profiles.

4.1.10. Blaming and dehumanizing victims

Offenders use multiple neutralization techniques. For example, offenders often blame victims for their own suffering, with the term “greedy” used to describe them. By doing so, fraudsters deflect their own guilt for their fraudulent actions and are therefore able to rationalize their actions (Barnor et al., 2020, Offei et al., 2020). Online romance fraudsters also dehumanize their victims, often using derogatory names (Lazarus, 2018). For instance, perpetrators employ specific terminology to describe their criminal activities and victims. While offenders often self-identify as "hunters," they dehumanize their victims by labeling them "game animals" (Lazarus, 2018, p.70). The leading cause of this dehumanization is not the distance networked computers create between victims and offenders but the necessity for objectification so that offenders see their victims as foolish and equate them to mindless objects. Indeed, online romance fraudsters generally perceive victims as unintelligent groups of people with poor mental faculties and a slower ability to detect fraudulent relationships (Cassiman, 2019, Lazarus, 2018). Having discussed insights from offender-oriented studies, we will now shift our focus to studies that center on the victims. We will also discuss the model that is most frequently utilized in this category.

4.2. Victim-focused studies mostly cast their gaze on the West

4.2.1. “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model”

The "Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model" is extensively used in the research of online romance fraud. This theory has been utilized across three categories of studies: offender-focused (e.g., Anesa, 2020), public-focused (e.g., Whitty, 2019), and victim-focused (e.g., Cross et al., 2018). The model has also shaped many other studies we excluded in this study (e.g., Dickinson et al., 2023, Wang and Topalli, 2022). Since the model is most commonly used in victim-based studies, it is discussed here.Whitty and Buchanan’s research on romance fraud and the techniques offenders use to defraud victims has been the most influential to date (e.g., Buchanan and Whitty, 2013; Whitty, 2013a, Whitty, 2013b). Their research involved three phases. Firstly, they administered an online survey to 796 individuals from a dating website and 397 individuals from a support site for fraud victims. Secondly, they analyzed 200 reports from victims on a social support group. Finally, they conducted face-to-face interviews with 20 victims.Whitty identified seven stages of online romance fraud based on these studies.2The stages are (1) the victim’s motivation to seek an ideal partner, (2) the presentation of an ideal profile to victims, (3) the grooming process, (4) the sting, (5) the continuation of the scam, (6) sexual abuse, and (7) re-victimization. Together, these stages form the ‘scammers persuasive techniques’ model. This leads to identifying the three key scammers’ techniques: the ‘foot-in-the-door,’ ‘door-in-the-face’ and sexual image-based abuse techniques.The ‘foot-in-the-door’ involves initially asking for a small sum and then escalating crises requiring more extensive sums after gaining the victim’s trust. The ‘face-in-the-door' involves asking for an extreme sum of money initially. After the initial request, the victim is asked for less money to convince them to give away their funds. After the grooming phase, the perpetrator usually creates a crisis phase. This entails them purposefully inventing false information, such as the victim losing their parents, needing travel papers, or having a loved one in the hospital and being asked to pay money. One additional strategy offenders employ involves acquiring sexually explicit webcam recordings of the target individual through the pretext of a romantic attachment. Subsequently, the perpetrator employs this tactic to extort money from the target (i.e., image-based sexual abuse).The scammers’ persuasive techniques model tends to suggest that the risks associated with online romance fraud are more pronounced for particular groups (Whitty, 2013a, Whitty, 2013b). However, while everyone is potentially vulnerable, insights from privacy and security risk advice remind us that vulnerability is indeed a complex and dynamic concept (e.g., Boyd et al., 2021, Castańeda et al., 2021). Individuals or groups can experience varying levels of vulnerability that can change over time (Smith, 2021, Boyd et al., 2021, Castańeda et al., 2021). Despite its value in providing a streamlined account of the stages through which the fraud progresses in online romance form, the model nevertheless faces some limitations.

4.2.2. Theoretical limitations and implications of “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model”

4.2.2.1. Advance fee fraud or the Nigerian 419 fraud

While Nigerian 419 fraud or Advance Fee Fraud predates the “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model,” stages of Whitty’s model bears many similarities to Nigerian 419 fraud or Advance Fee Fraud. Advance Fee Fraud is a fraudulent scheme in which individuals are deceived into providing nominal sums of money for a significantly greater financial benefit (Adogame, 2009, Oriola, 2005). The Advance Fee Fraud, commonly known as 419, is historically associated with fraudulent activities originating from Nigeria (Lazarus and Okolorie, 2019). The term "419" in fraud literature originates from the Nigerian Criminal Code's section 419, specifically dealing with fraudulent activities. Based on these insights, it is logical that the historical backdrop to the “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model” in online romance fraud is indeed the Advance Fee Fraud or Nigerian 419 fraud in West African cybercrime literature. While there is some acknowledgment of the connection in Whitty, (2013a) and Whitty, (2013b), the relevance of Advance Fee Fraud or Nigerian 419 fraud and the legacy and contribution of the scholars mostly of West African descent (Ampratwum, 2009, Apter, 1999, Ebbe, 1997, Igwe, 2007, Oriola, 2005) who have investigated it could have been acknowledged. Neglecting Advance Fee Fraud literature in the dominant online romance fraud theory implies an overstatement of originality.3 It also reprises the exclusion of West African scholars, such as Igwe (2007), Adogame (2009), Ampratwum (2009), Apter (1999), Ebbe (1997), and Oriola (2005), from discussions of online fraud, as noted by Lazarus (2020) and Cross (2018). In general, criminology has paid limited attention to scholars writing on these topics from formerly colonized African nations (Cohen, 1988, Kalunta-Crumpton and Agozino, 2004) due to colonial forces that tend to value the West’s contributions over those of West Africa and the Global South (Cohen, 1988, Ibrahim, 2015, Lazarus, 2020). If the works of West African scholars had been duly acknowledged, it prompts the question of what changes or modifications could have been made to the "Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model."The insights derived from the Nigerian 419 fraud format hold significance in examining online romance fraud, as they provide a valuable understanding of fraudsters' motivations, epistemologies, ideologies, and worldviews, including the dehumanization techniques they employ (Igwe, 2007). This could potentially enrich the theoretical framework by shedding light on the operational aspects and reception of fraud, leading to a more comprehensive understanding. Additionally, this integration could enhance Whitty's comprehension of the effective strategies employed by con artists and enable a better appreciation of the challenges faced by victims. Thus, our critique is not simply of a historical bias in citations but a failure to engage with the insights provided by African scholars and incorporate them into the model.It is crucial to clarify that the centrality of the work of West African scholars in our argument is based on the similarities between the long-standing Nigerian 419 fraud format and Whitty's model. This emphasis is not grounded in the assumption that Nigeria has a higher prevalence of online romance fraud perpetrators than other nations worldwide, such as Malaysia and Bulgaria. Instead, our argument underscores that the "Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model" has all the hallmarks of the Nigerian 419 fraud thesis. Yet, the model overlooked prior scholarly works on the Nigerian 419 fraud, also known as Advance Fee Fraud.

4.2.2.2. Moving beyond psychological accounts

The focus on the experience of victims means that the “Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model is individualized and does not pay attention to the wider contextual drivers of fraudulent behavior. Therefore, it tends to identify psychological drivers of responsiveness to fraud from the information provided by the victims. It would be beneficial to extend our understanding of victimization beyond the psychological literature to consider the broader societal and systemic factors enabling and supporting fraudulent behavior.

4.2.2.3. Limited scope

The “scammers persuasive technique theory” focuses on scammers’ techniques to manipulate their victims as experienced by the victims studied. However, this victim-focused approach does not comprehensively address the underlying factors contributing to fraudulent behavior. The theory provides a general overview of standard techniques fraudsters use. At the same time, a number of these techniques might be employed beyond online contexts, given that offline and online are intertwined in online romance frauds. For instance, Whitty, (2013a) and (2013b) used many examples to illustrate the stages of online romance fraud; however, the model could have benefitted from more contextual examples, and case studies focused on the practical aspects of fraud. To truly comprehend online romance fraud, having the theory informed by a richer array of real-life examples would have been beneficial. Having addressed these challenges and the limits to using the “scammers persuasive techniques model”, we turn to the key findings from the victim-based studies.

4.3. Perpetration techniques

The victim-based studies, whether or not adopting the “scammers persuasive techniques model” as a framework, highlight a range of scamming techniques that put psychological pressure on their victims to respond. These can be summarised as follows:

a. Urgency or scarcity: Online romance fraud offenders use health emergencies as a tactic to request money from victims (e.g., Carter, 2020; Cross and Holt, 2021). Frequently, these perpetrators maintain that they are unwell or have encountered an incident, such as a car crash, which necessitates prompt medical aid beyond their financial means. This tactic is effective because it elicits sympathy from the victim and requires a rapid response. For example, the offender might claim that they need surgery at a hospital, and time is of the essence (e.g., Cross and Holt, 2021). Creating a sense of urgency pressures their victims into making a quick decision within a limited time window to avoid penalties or negative consequences.

b. Authority or credibility: Fraudsters may use false or misleading credentials and occupations, such as military profiles, to make them feel legitimate or trustworthy (e.g., Cross and Holt, 2021). They may claim to be a government official, a bank representative, or an employee of trusted organizations.

c. Establishing rapport: Fraudsters may use techniques designed to exploit their victims’ emotions or desires (e.g., Carter, 2020). For example, they may use sympathy or flattery to gain their victims’ trust.

d. Fear or intimidation: Fraudsters may also use fear or intimidation to coerce their victims into compliance. For example, they may threaten legal action or imply that harm will come to the victim or their loved ones (e.g., Buchanan and Whitty, 2013, Carter, 2020).

e. Phishing: Fraudulent actors may employ phishing techniques to deceive their targets into divulging confidential information, including financial particulars or login credentials (e.g., Cross and Holt, 2021; Cross and Layt, 2021). This may involve creating fake profiles on dating websites.

4.4. Gaps and potential biases in the literature

Our review identified several critical issues within the broad online romance fraud research field, which require further consideration.

First, aside from Barnor et al. (2020) and Cassiman (2019), none of the studies directly offered offenders’ perspectives or had any direct and in-depth engagement with actual offenders. For example, Offei et al.’s (2020) work gathered 320 responses from people at internet cafes, which are considered hotspots for online romance fraudsters. But some (or indeed most) of these respondents may not be online fraudsters because non-offenders also used these internet cafés in Ghana. Similarly, for assertions about online fraudsters, Lazarus (2018) used music lyrics allegedly authored by ex-cybercriminals and their allies. The authors of most or some of these lyrics may not be online fraudsters themselves. Of those studies which did offer something of the offenders’ perspectives, there was a reliance upon online data sources such as dating profiles (Kopp et al., 2015), “offenders’ messages” (Anesa, 2020), “scammers’ adverts” (Jakobsoon, 2016) and “scammers profiles” (Suarez-Tangil et al., 2020). For example, Kopp et al., 2015 used 37 blocklisted dating profiles to generate their analysis of online romance fraud offenders. While these methods provide insight into the self-presentation and tactics of offenders, they do not engage directly with these offenders to provide a deep understanding and comprehensive analysis of motivations, habits, and rationales. This limits our understanding of the characteristics of fraudsters and their “scamming techniques.”

Second, there appeared to be a lack of engagement with other fraud studies. Romance fraud was treated as an isolated phenomenon rather than one of a portfolio of options for fraud offered by the digital network. In addition, details of the operation method or perpetration techniques were sometimes missing. For example, Barnor et al. (2020) conducted ten face-to-face interviews and did not focus on how online romance fraud was merged with claims of supernatural powers. While some offender-focused studies (Cassiman, 2019, Lazarus, 2018) did mention cyber spiritualism, they did not engage with them in depth due to the specific scope of their studies.

‘Cyber Spiritualism’ is a term used to describe a situation where fraudsters invoke supernatural powers to aid their online fraud4 (Lazarus, 2019). In West Africa, some cyber fraudsters believe that the adoption of supernatural strategies, known as cyber spiritualism, is a means to enhance their success in defrauding individuals and organizations (Alhassan and Ridwan, 2021, Lazarus and Okolorie, 2019, Monsurat, 2020, Newell, 2021, Riedel, 2015). By the same token, some criminals believe that incorporating these supernatural tactics minimizes the likelihood of being apprehended by law enforcement agencies, as Lazarus and Okolorie’s (2019) study discussed. Following the rise of online romance fraud, such tactics are commonly employed by ‘Yahoo Boys' in Nigeria (Lazarus, 2019, Tade, 2013) and ‘Sakawa Boys’ in Ghana (Alhassan and Ridwan, 2021, Oduro-Frimpong, 2014). If individuals who commit online romance fraud believe that using supernatural strategies can increase their chances of success in defrauding their victims, these beliefs may have real consequences in terms of their practices and approaches (drawing from symbolic interactionists’ insights, such as Thomas, 1923; Thomas and Thomas, 1928).

The absence of the spiritual dimension of online romance fraud is noteworthy as it has been identified as a core aspect, at least of West African online fraudsters in the broader literature. For example, the literature has highlighted online fraudsters' spiritual beliefs and utilization of supernatural powers as a significant aspect to consider in Ghana (Alhassan and Ridwan, 2021, Oduro-Frimpong, 2014, Riedel, 2015), Nigeria (Lazarus, 2019, Lazarus and Okolorie, 2019, Melvin and Ayotunde, 2010, Tade, 2013), and Côte d′Ivoire (Newell, 2021). For other parts of the world, our understanding of online fraudsters' motivations and tactics, particularly romance fraudsters, is much sketchier. The skew towards publications originating from the Global North that the review identified – and was in part a consequence of the selection criteria employed – may explain these limitations in analyzing the cultural context of offender motivations. It is likely that the assumptions on the part of online romance fraudsters in the West African regions that invoking spells or releasing oratory postulations can effectively control victims is clearly crucial to understanding their motivations and modus operandi. Yet this and other cultural factors were only given limited consideration in the offender-focused literature that we identified for this review. Certainly, online romance fraud is a complex issue that requires both victim and perpetrator perspectives to be fully understood.

While victim-focused studies (e.g., Cross and Layt, 2021, Cross et al., 2018, Modic and Anderson, 2015, Whitty, 2013a, Whitty and Buchanan, 2016) have provided valuable insights into the phenomenon, it is critical to recognize their limitations. Online romance fraud involves both perpetrators and victims, who are two sides of the same coin. Focusing solely on victims restricts our understanding of the perpetrators, including their worldviews, ideologies, mindsets, and methods of operation. We need to advance our knowledge of both victim and perpetrator perspectives. By combining victim and perpetrator perspectives, researchers can develop more effective prevention, intervention, and enforcement measures considering the nuances of online romance fraud victimization. Filling these gaps would also help us better appreciate the vulnerabilities of romance fraud victims.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review suggested that a small body of research into online romance fraud has developed, which remains somewhat fragmented and lacks theoretical consistency. While some encouraging progress has been made, overarching theoretical insights are sparse, and the studies, by and large, do not particularly highlight the general and more specific features of online romance fraud compared to other online fraud types. A greater share of the studies we identified was qualitative, perhaps due to the challenges of accessing large, representative samples of victims (or those at risk) and perpetrators. They tend to be dependent upon small, relatively homogenous respondent groups. As a result, there is a lack of generalisability and reproducibility within available studies. In particular, as we have noted, there is limited attention to the full range of methods deployed by online romance fraudsters. There is also only limited acknowledgment of the relevance of the global nature of romance fraud and the specific regional influences which generate it, and the forms it takes. Though West Africa is a significant center for originating such frauds, more attention could be paid to how cultural factors specific to this region influence the motivations and methods of fraudsters there. Beyond this, we have little understanding of all of the fraud originating from other areas, which would enable a more complete global account and framework to be developed. The bias towards research publications originating in the Global North and the still niche research focus in this area, as indicated by the dominance of certain authors, comes through clearly from this review.