Abstract

Background: Involuntary civil commitment (ICC) is a court-mandated process to place people who use drugs (PWUD) into substance use treatment. Research on ICC effectiveness is mixed, but suggests that coercive drug treatment like ICC is harmful and can produce a number of adverse outcomes. We qualitatively examined the experiences and outcomes of ICC among PWUD in Massachusetts.

Methods: Data for this analysis were collected between 2017 and 2023 as part of a mixed-methods study of Massachusetts residents who disclosed illicit drug use in the past 30-days. We examined the transcripts of 42 participants who completed in-depth interviews and self-reported ICC. Transcripts were coded and thematically analysed using inductive and deductive approaches to understand the diversity of ICC experiences.

Results: Participants were predominantly male (57 %), white (71 %), age 31–40 (50 %), and stably housed (67 %). All participants experienced ICC at least once; half reported multiple ICCs. Participants highlighted perceptions of ICC for substance use treatment in Massachusetts. Themes surrounding ICC experience included: positive and negative treatment experience’s, strategies for evading ICC, disrupting access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and contributing to continued substance use and risk following release.

Conclusions: PWUD experience farther-reaching health and social consequences beyond the immediate outcomes of an ICC. Findings suggest opportunities to amend ICC to facilitate more positive outcomes and experiences, such as providing sufficient access to MOUD and de-criminalizing the ICC processes. Policymakers, public health, and criminal justice professionals should consider possible unintended consequences of ICC on PWUD.

1. Introduction

Involuntary civil commitment (ICC) for substance use treatment is legal and used by 38 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (Christopher et al., 2020a; Evans et al., 2020). Massachusetts’ statute for ICC is defined under General Law 123 as “Section 35,” indicating that a qualified person may request a court order for ICC for an alcohol or substance use disorder (SUD) (Massachusetts General Laws ch. 123, § 35, 2023). Petitions for ICC under Section 35 are executed in district courts and can be initiated by police officers, court officials, physicians, family members, guardians, or oneself.1 More recently, ICC has been used to combat challenges related to fentanyl entering the drug supply and has been used as a tool in post-overdose outreach programs for overdose survivors or their families to initiate petitions and facilitate entry into treatment (Carroll et al., 2023; Christopher et al., 2018; Tori et al., 2022). ICC is granted by the court if there is a likelihood of serious harm to oneself or others as a result of their SUD (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2019). Section 35 warrants further empirical investigation, as it has been frequently applied in Massachusetts (Christopher et al., 2015; Evans et al., 2020; Walt et al., 2022) despite mixed evidence on its effectiveness in improving treatment, reducing substance use or overdose mortality, and exacerbating feelings of psychological distress (Chau et al., 2021; Christopher et al., 2018; Lamoureux et al., 2017; Werb et al., 2016).

Several U.S and international studies suggest that ICC is a coercive process to those subjected to it through violations of individual autonomy and freedom (Chieze et al., 2021; Shozi et al., 2023; Silva et al., 2023). Diminished perceptions of autonomy often result in resistance to treatment processes, which has been demonstrated to reduce treatment effectiveness (Udwadia and Illes, 2020). Other major challenges arise with respect to legal coercion into treatment due to ethical and motivational concerns and the ongoing tension between the legal system and treatment providers (Mackain and Lecci, 2010). Research in the U.S. on ICC identifies a number of adverse outcomes, such as return to use, recidivism, fatal and non-fatal overdose, and feelings of psychological distress (Gowan and Whetstone, 2012; Lamoureux et al., 2017; Werb et al., 2016). Internationally, ICC is often framed as compulsory commitment to care or compulsory care (Israelsson, 2011; Israelsson et al., 2015; Mfoafo-M’Carthy and Williams, 2010). Much like the U.S., international programs often differ with respect to what societal challenges that civil commitment is used to address. For instance, some international compulsory programs focus specifically on drug use (Parker et al., 2022; Rafful et al., 2020) while others emphasis mental health (Mfoafo-M’Carthy and Williams, 2010; Shozi et al., 2023). Research internationally has also shown a range of negative outcomes for people placed in involuntary treatment, with some highlighting adverse effects like non-fatal overdose and risk of exposure to violence (Hall et al., 2015; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh et al., 2018; Rafful et al., 2018).

In Massachusetts, ICC facilities are overseen by the Department of Public Health (DPH), the Department of Mental Health (DMH), and the Department of Corrections (DOC) (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2019, 2023). DOC-run facilities may more closely resemble carceral settings rather than traditional treatment programs (Walt et al., 2022). Some research finds that people in SUD treatment view ICC as a better alternative to prison or overdose, while providers report ICC eases a family’s concerns about a loved one’s SUD, and forces needed screening and care initiation, even if ICC acts as an extension of the criminal justice system (Evans et al., 2020; Gowan and Whetstone, 2012). Limited research has been conducted with out-of-treatment populations who have recently experienced ICC; individuals in recovery and providers from healthcare institutions able to commit or receive committed patients may present biased views on ICC.

This study aims to contribute to the literature on ICC by qualitatively investigating the self-reported experiences and outcomes of a sample of people who use drugs (PWUD) subjected to the Massachusetts Section 35 court-ordered process, placement, and treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and design

The current study represents a secondary analysis of the Massachusetts Section 35 statute by utilizing qualitative data collected from a sequential mixed-methods rapid assessment study of PWUD conducted between 2017 and 2023 (Hughto et al., 2023; Shrestha et al., 2021, 2024). Individuals in our parent study were purposively and conveniently sampled through street-based recruitment and partnerships with community-based organizations (Benrubi et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022). Our recruitment process was comprehensive and involved environmental scans, including reviewing public health and surveillance data, conducting ethnographic observations, and meeting with community partners to identify recruitment locations. Strategies differed by study location, but all employed purposive sampling to recruit participants from high drug use, arrest, and overdose areas (Hughto et al., 2022). Following recruitment, prospective participants were screened for eligibility prior to providing verbal consent to participate. Eligible participants were: (1) 18 years old or older; (2) resided in one of fifteen high-risk overdose communities in Massachusetts, including Boston, Chicopee, “Cape Cod” (Barnstable, Dennis, Falmouth, Mashpee, Orleans, Truro), Greenfield, Lawrence, Lowell, New Bedford, “North Shore” (Beverly, Lynn, Peabody, Salem), Fitchburg, Salisbury, Quincy, and Springfield, and (3) had used an illicit drug in the last 30 days.

All enrolled participants completed a one-time survey. Following completion of the survey, about one-third of all participants were offered and consented to participation in a semi-structured interview with trained research staff if they demonstrated (via their survey responses) a willingness to discuss personal experiences pertaining to illicit drug use, treatment, housing and other related experiences. In the broader parent study, 303 participants completed a qualitative interview that explored questions related to participants’ substance use history and related experiences, unique or extensive substance use patterns, experiences of witnessed or personal overdose, experiences accessing harm reduction and treatment services, experiences with the criminal-legal system, and more. The current study focused specifically on a subset of interview questions within the larger interview guide that aimed at understanding participants’ perspectives and experiences with ICC through Section 35. If participants disclosed during the survey that they had ever been placed on a Section 35, they were then asked a variety of follow-up questions during the interview. For instance, participants were asked to elaborate on their ICC experience, such as: “What happened after you left the Section 35 facility?”, “What was your drug use like afterwards?” and “Has the Section 35 experience changed how you react in an overdose situation?” (See Appendix).

Interviews from the parent study spanned approximately 45 minutes, were audio-recorded, and professionally transcribed. Most interviews were conducted in English with few conducted in Spanish. Participants were compensated with gift cards or cash for their time and expertise, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University Medical Campus and Brandeis University. During interviews, study participants were informed they could take breaks as needed, refuse to answer specific questions if uncomfortable, and to opt-out at any point in the interview without retaliation for any reason. Our study follows the standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) to provide transparency across our data collection and analysis (O’Brien et al., 2014).

2.2. Analysis

All interview transcripts were imported into NVivo 20 (QSR, International, Version 20), and analyzed using inductive and deductive approaches. Prior to analysis, a codebook was created that mirrored core areas of investigation covered in the interview guide. Through discussion at weekly team meetings, codes were then inductively added to the codebook over time as new thematic areas emerged (Hughto et al., 2022). The initial coding was conducted using a rapid, first-cycle approach (Wicks, 2017). Following this, approximately 25 % of transcripts were double-coded by the research team to ensure consistency.

In the current study, we conducted a secondary analysis focused on understanding ICC experiences through the parent code “Section 35”. As mentioned above, if participants disclosed during the survey that they had ever experienced an ICC through Section 35, interviewers were instructed to probe further about the participants’ perceptions of said experience(s). Data from the aggregate Section 35 parent code were revisited within the existing NVivo data file. The first and second author implemented memo-writing, open coding, and focused secondary coding to inductively identify and parcel out subcodes relating to participants’ views and experiences of ICC within the broader Section 35 parent code (Cascio et al., 2019; Charmaz, 2006; Charmaz and Belgrave, 2015). Our coding approach was iterative whereby emergent themes were identified by both coders and refined for consensus throughout the coding process. Coders met weekly to reconcile discrepancies, discuss subthemes, reflect on their biases, positionality and to further conceptualize the data through intercoder consensus (Cascio et al., 2019).

2.3. Sample

Of 303 interviews conducted between 2017 and 2023, fifty-three met the initial criteria (self-reported experiences with Section 35) for inclusion in this analysis. Upon further review of transcripts, eleven participants were removed due to (1) lack of personal experiences of ICC or (2) conflating Section 12 (Mental Health ICC) experience with a Section 35 experience (Massachusetts General Laws ch. 123, § 12, 2023). Our final qualitative sample included 42 participants who experienced ICC through Section 35.

3. Results

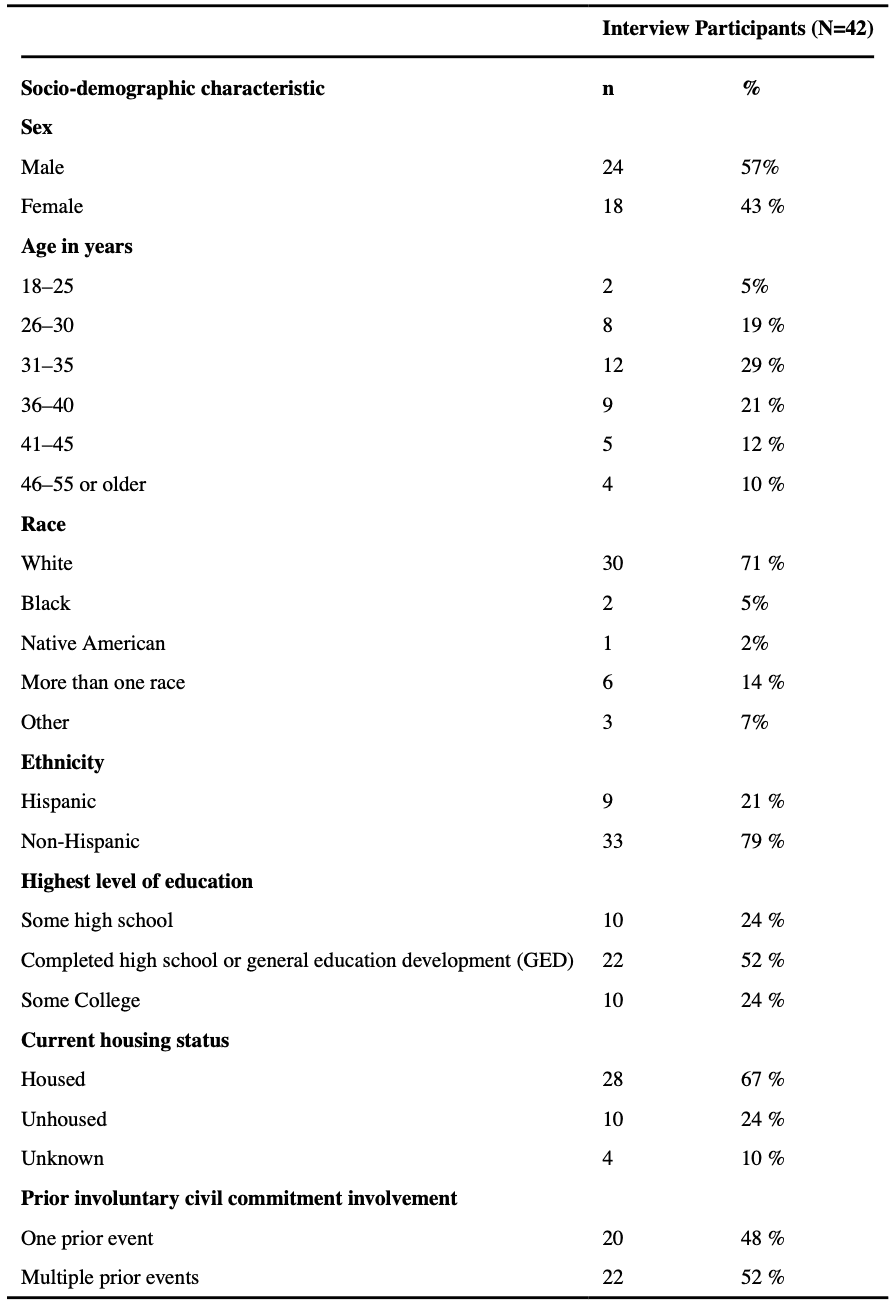

Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the sample. Participants were predominantly male (57 %), white (71 %), between the ages of 31 and 40 (50 %), and had stable housing (67 %). All participants experienced ICC at least once, and half disclosed multiple ICC experiences. These demographics provide a snapshot of the people in our sample who experienced ICC in Massachusetts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Self-reported socio-demographic characteristics of 42 interview participants with histories of involuntary civil commitment (ICC) in the state of Massachusetts, 2017–2023.

3.1. ICC experiences

Interviews with participants demonstrated diverse attitudes and experiences of ICC through their perceptions and knowledge of the ICC process in Massachusetts.

3.1.1. Positive experiences

Although most participants described ICC as coercive and harmful, a subset of participants described positive experiences. For instance, some participants identified the informal peer support they gained as a factor that helped them to engage in treatment while in ICC facilities. One participant shared:

I don’t think it was the facility. I think it was the fact that I found my peers. It was more peer support. I found people like me willing to give it a shot. – Male, Fitchburg

Some participants connected positive ICC experiences to the accessibility of fundamental basic needs such as food, personal freedoms like being able to smoke cigarettes, and ethical medical care like the ability to access medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) or other comfort medications to aid in detoxification from opioids. One participant recalled how her ICC experience improved her health:

It [DPH ICC facility] was awesome. We were able to smoke. I still got my methadone and I felt awesome there. I gained weight. You know? I feel much better. I felt like death before. – Female, New Bedford

Those who described positive experiences often highlighted the availability of mental health and SUD programming such as groups, counseling, and education in the facility. When comparing multiple ICC treatment experiences at a DPH-run ICC facility with that of a DOC-run ICC facility, one participant explained:

It [DPH ICC facility] was better run…organized groups, everything organized. I mean, you weren’t walking around with your jumpsuit on. Everything was better. The options, halfway houses, treatment plans afterwards, and, you’d meet with your counselor once every couple of days. It was more helpful. I mean, it wasn’t great, but it was a good, decent place. – Male, Mashpee

A subset of participants reported that they had self-initiated an ICC. They indicated that self-initiating ICC was typically used as a last resort when they felt constrained with no other option to receive care. For example, some participants described a lack of detoxification and SUD treatment availability in their community and indicated that they initiated ICC themselves to obtain services:

I had tried to go to the hospital and couldn’t get a bed and all, so that’s how I ended up [in ICC], I’m like I know how to get a bed, let me [ICC]. – Female, New Bedford

Relatedly, several participants reported self-initiated ICC as an effective means of avoiding incarceration, especially because detox during incarceration in Massachusetts would most likely occur without the aid of MOUD or tailored care, as noted by the following participant:

I did it [self-initiated ICC] because I knew I wasn’t getting out of jail, and I didn’t want to kick the dope in jail. I’d rather go, come off of it with nothing or on Suboxone [buprenorphine] or whatever then be feeling better and able to go to jail. – Male, Quincy

3.1.2. Negative experiences

Although some participants noted positive factors relating to ICC, frequently participants discussed negative ICC experiences, with some facility types being more problematic than others. Notably, participants emphasized concerns with medication access across sites and the stigmatizing effect of being placed in a carceral facility for SUD treatment as contributors to their overall negative experience.

3.1.3. Medication access

One major limitation cited by participants was the provision of MOUD during ICC, and this was not specific to the type of ICC facility experience (i.e., DOC- or non-DOC run). While some spoke positively about MOUD access, others described being given an insufficient dosage or denied MOUD entirely, causing disruptions to previously established medication regimens:

They’re [ICC facilities] starting to give people their methadone. If they’re on methadone, they’ll give you the methadone, but they’re not going to give you the full dose. If you’re on 200 milligrams, they’re gonna cut it and make it less. So yeah, they need to continue doing that, cause it’s clogging the system up… It’s clogging their infirmaries up…It’s making them work harder than people that are doing time that aren’t getting the medical care that they need. – Male, Lynn

Similarly, participants discussed challenges with medication access more broadly, citing that ICC facilities lacked the medications that would typically be provided to treat clients who primarily use substances other than opioids, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines. In these instances, participants noted that denying access to these medications resulted in severe health consequences, such as seizures:

They [ICC facilities] don’t care. I mean, you could be with people they’re withdrawing and if you withdraw from benzos or alcohol, you can have seizures and die coming off it and they’re not medicating people properly. So, people would have seizures. A kid actually had a seizure from them not medicating him, not being medicated properly, fell over and split his head open and got 15 staples in his head because they weren’t medicating him the right way. – Male, Boston

These concerns suggest that there are gaps in the medical treatment and a discontinuity of MOUD care that are created and exacerbated by the experience of ICC.

3.1.4. Criminalization

In addition to issues around medication access, some participants attributed their negative experiences to the similarities between their DOC-run ICC facilities and jail or prison. During the timespan of our study there were three DOC-run ICC sites in operation, and judges - not clinicians - decided upon placement there. Participants reflected on their experiences at these locations and listed comparable institutional processes to that of jail or prison, such as the requirement to wear correctional uniforms or pay for telephone calls:

They take you to a [DOC ICC facility], which is a prison and they lock you up in the Department of Corrections jail uniforms and it’s like jail. You have a canteen. You’re locked in there. There’s a razor wire fence around it. There are correctional officers. I got beat up by a correctional officer last time I was in there. It’s jail. – Male, Lowell

Further, many participants discussed insufficient access to mental health and SUD treatment at the DOC facility where they were placed for ICC. This disconnect contributed to the impression that they were being incarcerated for their substance use rather than being treated for a chronic condition during their ICC. One participant who was involuntarily committed multiple times explained:

It’s the worst experience [DOC ICC facility]. It’s not a treatment facility at all. They did absolutely nothing there for me. I sat there pretty much all the way for 40 days. I think, I’d seen my counselor twice the whole time I was there and food’s terrible, the staff were very rude and it was terrible. It wasn’t a level of care at all. Really, they just hold you there and they just release you at this, because they have to hold you for a certain amount of time and they just release you after you’re done. – Male, Salisbury

Notably, no participants from DPH or DMH-run facilities described comparable perceptions, treatment, or experiences of criminalization.

3.2. ICC outcomes

Participants linked several different outcomes to the experience of ICC, highlighting instances where coercive treatment was either ineffective in changing the participants’ circumstances, ineffective in reducing substance use, or was believed to elevate physical or social risk.

3.2.1. Ineffective treatment

Participants described being less invested in their treatment following ICC experience(s) and criticized the idea of forcing someone into treatment before they were ready, as noted by a participant from the North Shore area of Massachusetts:

Forcing somebody to get clean that doesn’t wanna get clean, you’re not helping anybody. You think you are but you’re not helping that person, you’re not…You’re just making it easier for them to overdose in three weeks when they get out, because they’re not ready to get clean. If you had to put them in handcuffs and shackles, and forcibly bring them into a treatment program, they clearly don’t wanna go, you know what I mean? So, I mean, they’re still ready to get high when they get out. - Male, Salem

Relatedly, participants noted that their readiness to receive treatment impacted the effectiveness of their experience. Several participants explained that, while their ICC petitioners may have been ready for them to engage with treatment, the participants themselves were not yet ready to do so. As a consequence, they did not fully maximize the resources and wraparound services available. One participant explained her perspective and detailed the ineffectiveness of her ICC:

At the time I wasn’t ready to stay clean so I didn’t use all their options that they were giving me. So, I’m sure that somebody that really does end up wanting help over there they can get a lot out of it. – Female, Lawrence

These statements reinforce that outcomes associated with ICC are dependent on a person’s willingness to engage with treatment and that coerced treatment like ICC may not be an effective alternative to voluntary treatment.

3.2.2. Increased use and overdose risk

In discussions about abstinence or substance use following release from an ICC facility, most participants felt it was common to return to using substances immediately after discharge. Some participants believed that experiencing ICC resulted in increased risks:

They’re so quick to section [ICC] people and shove them through a door and lock them up. Once they get out, these people just want to come out and use again, but heavier. Next thing you know it, you’ve got another fucking body. – Male, Lowell

Participants drew similar conclusions about overdose risk following ICC, linking their ICC experience with lowered tolerance and thus resulting in higher risk of overdose. One participant described how he felt that any potential benefit of ICC was eclipsed by the more dangerous outcomes following release:

I think it’s wrong [ICC]. It doesn’t help anybody. If anything, it brings you closer to fuckin’ killing yourself. It’s more hurtful than helpful I think for heroin addicts. I don’t know how, with booze…Like, if you’re not ready to get help, forcing somebody into a program isn’t doing anything but lowering their tolerance so they can come out and kill themselves unintentionally – Male, Lynn

Still, some participants described being abstinent from substances following their ICC experience(s). They noted in some cases, that it was the trauma of their ICC experience rather than a supportive treatment environment that motivated them to remain abstinent.

You know what the crazy thing is? Because I went through that awful, horrific thing [ICC], I stayed sober for like three years. So, sometimes, again, here’s the paradox, that like, sometimes that’s the best thing for an addict, is to sit through a living hell for three weeks or whatever it is and then maybe that pain is what keeps us sober. – Male, Mashpee

The increased risk of adverse outcomes post ICC as described by participants likely influenced perceptions of ICC as dangerous and ineffective.

3.2.3. Strategies for evading ICC

A prominent theme in participants’ discussions of the consequences of their ICC experiences was highlighted through participants descriptions of evading actors who enforced ICC. Participants described how knowledge of ICC shaped their decision-making processes, like avoiding contact with the police or leaving the state to circumvent an ICC. One participant detailed what he believed to be common knowledge of how to avoid the process. He stated:

Everybody knows, to beat a section [ICC], all you got to do is skip town for 72-hours. You know? That’s if you find out. You’ve got to have somebody on the inside. You’ve got to have a mole. – Male, Barnstable

Similarly, another participant discussed her ability to evade ICC following her pregnancy:

It [ICC] was right after I had my daughter, and they sectioned [involuntarily committed] me…I had been living in a family shelter while I was pregnant, because I got sober while I was pregnant, I did really good. And, then I had a huge incident during my pregnancy, but, after my daughter came, I ended up relapsing. But, I ran from it [ICC]…I was home by the end of the night. – Female, Boston

Participants also spoke about their hesitation in seeking help in an emergency because of fears associated with interacting with police. Police may wield ICC either in these instances or as part of post-overdose outreach visits to overdose survivors and their family. Because many police conduct post-overdose outreach in Massachusetts, they can petition the court to initiate ICC, and also are charged with enforcing ICC processes (e.g., civil arrest, transportation to facilities), participants linked ICC with an increased fear and avoidance of police. A participant explained his apprehension:

It used to be that people didn’t mind talking to the cops because it wasn’t like they were going to get in trouble for it, but now that everybody is so scared of [ICC]. I don’t even want to talk to the cops. Literally, if I overdosed, I would try to stay away from them for as long as it took for them—for the [ICC] to run out. So, if I overdosed, I’d disappear for a week. I’d leave town for a week because I wouldn’t want to get picked up on an [ICC]. – Male, Lowell

In turn, the fear of ICC as a consequence of substance use as described by participants served to facilitate opportunities to learn how to evade these processes.

4. Discussion

We documented varied experiences of ICC among PWUD in Massachusetts and examined how these experiences can inform future ICC adaptions and policies. For instance, some participants spoke about learning to evade an ICC entirely due to fear of the carceral system, while others referenced using ICC to their advantage to receive treatment on demand. These findings expand on prior ICC research (Christopher et al., 2018; Slocum et al., 2023) with diverse populations and provide more context on experiences and outcomes of ICC among PWUD in Massachusetts (Slocum et al., 2023). Results can inform policies and practices within the scope of licensed ICC treatment services in Massachusetts and beyond.

Our research identified several facilitators of positive ICC treatment experiences. Some participants spoke about peer support and new social bonds established within ICC facilities as motivating factors to engage with treatment and cited flexible policies as facilitating more pleasant experiences. Research finds that the development of therapeutic communities through communal group work and the establishment of social bonds with peers can be an effective means of cultivating an effective treatment atmosphere (Vanderplasschen et al., 2013). When site policies were more strictly enforced, the internalized stigma of drug use and trauma of a coercive environment amplified the negativity of the ICC experiences. Flexible policies and ethical care provision give participants autonomy in their day-to-day experiences, which increases readiness for and retention in treatment. Additionally, the experience of individuals who self-initiated ICC appeared to be different from those whose path was more fundamentally involuntary. This phenomenon supports the need for more readily available, on-demand, and low-barrier treatment options, instead of using ICC to access treatment.

The involuntary aspect of ICC, compounded by the carceral facilities into which participants in Massachusetts were randomly placed, are trauma-inducing, not trauma-informed approaches. PWUD often have traumatic histories with the criminal justice system (McKim, 2017; Walt et al., 2022) and may avoid processes like ICC as a means of preventing further exposure to psychological trauma (Baigent, 2012; Santucci, 2012). Continued research is needed to further examine the ethical considerations of coercive treatment as well as its ability to effect longitudinal treatment outcomes and mortality risk reductions to PWUD who are involuntarily placed into treatment (Christopher et al., 2020b; Coffey et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2020; Mackain and Lecci, 2010).

ICC disrupts established health and substance use patterns that may be risk-neutral or protective. Participants shared that ICC abruptly halted their substance use, which can change tolerance, increase risk of return to use, and cause fatal overdose following release from ICC. Other research from Massachusetts detected similar patterns of return to use (Christopher et al., 2018) and indicates that people completing involuntary treatment may be more likely to overdose than those who complete voluntary treatment (Messinger et al., 2022; Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2019). This is consistent with international literature finding that there is greater risk of overdose following compulsory treatment experiences (Hall et al., 2015; Rafful et al., 2018). By extension, an individual’s engagement with risk reduction services and access to preventative supplies (e.g., naloxone, sterile syringes) known to prevent morbidity and mortality (National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 2020) may also be disrupted by ICC. None of our participants described utilization of post-ICC discharge supports or harm reduction supply provision.

The common use of ICC in Massachusetts confirmed several known impacts of this process on public health and uncovered additional areas of concern. Participants who had distressing ICC experiences spoke to their disinterest in treatment and recovery programming, as prior research has also found (Klag et al., 2005). For some, fears of coercion through ICC—initiated by family or institutions like hospitals or police—made them less likely to seek help, call 911 in an emergency like overdose, and, as others have documented, to obtain treatment voluntarily (Christopher et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2018; Mackain and Lecci, 2010). In Massachusetts, as in many other states, an emergency call for overdose triggers a post-overdose outreach visit by a clinician or police-led team that may wield court-ordered ICC as an actionable resource (Carroll et al., 2023). The role of ICC in post-overdose outreach programming and, more fundamentally, of police in initiating and enforcing ICC for vulnerable populations like PWUD should be reconsidered, if the goals are to reduce overdose risk and encourage help seeking. Our findings highlight the continued need to improve the processes associated with ICC treatment, while also removing the pervasive fear of criminalizing or punishing people for their substance use. In removing the police and other aspects of the criminal justice system like the DOC from the ICC process, states like Massachusetts and countries that incorporate punitive mechanisms can transform ICC to a medicalized process. For instance, utilizing peer specialists, a model already in place for ICC related to mental health, could be adapted to facilitate substance use treatment (Rowe, 2013).

ICC facilities have documented challenges with accessibility to MOUD (Connery, 2015; Messinger et al., 2022), despite that it is guaranteed under Massachusetts law (Massachusetts General Laws ch. 123, § 35, 2023). Our findings further indicate that even when accessible, concerns regarding the quality of treatment persist. Our findings question the adequacy of ICC facilities to medically treat withdrawal from other substances like alcohol or benzodiazepines, which can cause serious health challenges. Standard, detoxification programs and emergency departments regularly treat withdrawal (Thornton et al., 2021; Wolf et al., 2020) and, in some countries and at least one U.S. state, community pharmacies may oversee withdrawal supports (Green et al., 2024; Haber et al., 2021). Taken together, the documented challenges call for changes in the ICC continuum: from screening and assessment of individuals at entry, to how treatment medications are prescribed and delivered within ICC facilities, to how individuals are equipped with referrals and harm reduction supplies to keep safe and promote ongoing treatment goals (Messinger et al., 2022). Revisions to existing policies are necessary to promote long-term benefits following ICC and mitigate potential harms of ICC.

This analysis has several limitations. While questions regarding ICC were posed, it was not the parent study’s sole focus; thus, some interview data were richer than others. Our sample was also recruited through community partner referrals and street-based outreach and only represents a portion of people who experienced ICC. Since our data are cross-sectional and enrollment in the study required participants to disclose active drug use, we only spoke with people who were still using substances following their ICC. Therefore, missing from our sample are people who experienced ICC who no longer actively use substances. This may be one reason why we heard more about negative ICC experiences in our analysis. Additionally, this was a secondary analysis that focused on Massachusetts and may not generalize to other jurisdictions or countries. Nuances of existing and newly updated ICC laws across U.S. states and territories are actively being catalogued (The Action Lab, 2024); expansion of these laws suggest that the experiences of PWUD may be of continued relevance. We also note that self-reported ICC experiences are subject to recall and social-desirability bias. Data were collected over five years and reflect lived experience at one point in time. Nonetheless, the major themes persisted throughout the period of inquiry and warrant consideration.

5. Conclusions

PWUD experience far-reaching health and social consequences beyond the immediate ICC effects. Areas of improvement and adaptation for ICC facilities, should they continue to exist in Massachusetts, include both ICC alternatives and changes to ICC initiation, orientation, operations, services provided, and safety policies. More research is needed with respect to self-initiation of, the ethics, and the setting of ICC, especially when facilities emulate carceral settings and may exacerbate previous traumas with incarceration.