Abstract

Treatment rates for alcohol use disorder (AUD) are low1 (eg, 7.6% in 20192). The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 evidence-based medications for treating AUD (MAUD) since 1949.3 To improve use of MAUD, the American Psychiatric Association released guidelines for pharmacological treatments of patients with AUD in 2017.4 However, little is known about prevalence and associations of using MAUD among US adults with AUD.

Methods

Data were from 42 739 adults 18 years and older who participated in the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), providing representative data among US civilian, noninstitutionalized populations,2 including sociodemographic characteristics, past-year emergency department (ED) visits, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and receipt of mental health care and any alcohol use treatment (eg, at a specialty facility, ED, private physician’s office, self-help group). Using DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, NSDUH assessed past-year illicit drug use disorder, AUD (DSM-IV dependence or abuse category), and major depressive episode. NSDUH data collection (through personal visits, using audio computer-assisted self-administered interviews) was approved by the institutional review board at RTI International. Respondents provided verbal informed consent.

The 2019 NSDUH is the first nationally representative survey asking respondents with past-year receipt of alcohol use treatment to report whether they used medications (eg, acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone oral/long-acting injectable formulations) prescribed by a physician or other health care professional to help reduce or stop alcohol use. The weighted response rate of the 2019 NSDUH was 45.8%.2

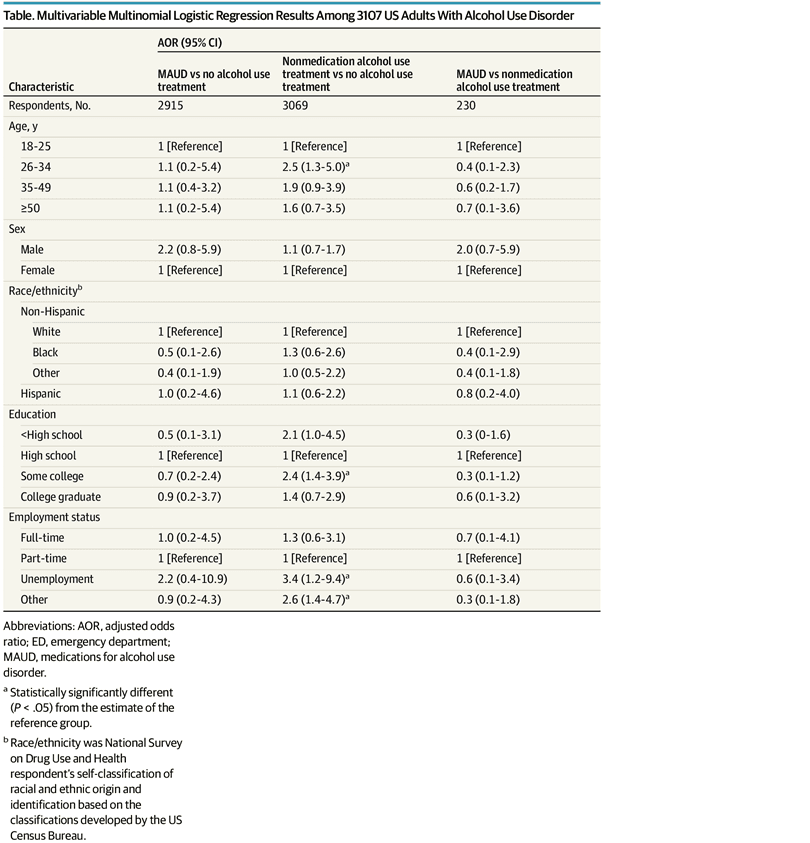

We estimated prevalence of MAUD among US adults with AUD. Multivariable multinomial logistic regression modeling was applied to examine associations of using MAUD and differences between using MAUD and receiving non-MAUD alcohol use treatment. We used 2-sided t tests to calculate P values, and significance was set at a P value less than .05. SUDAAN software version 11.0.1 (RTI International) was used to conduct analyses, accounting for NSDUH’s complex design and sampling weights.

Results

Of 42 739 included adults, 22 807 (53.4%) were female. Among US adults in 2019, past-year prevalence of AUD was 5.6% (95% CI, 5.3-6.0), or 14.1 million persons (95% CI, 13.2-15.1). Among the 14.1 million adults with past-year AUD, 7.3% (95% CI, 5.8-8.8), or 1.0 million persons (95% CI, 0.8-1.2), reported receiving any alcohol use treatment in the past year, and 1.6% (95% CI, 0.9-2.3), or 223 000 persons (95% CI, 127 000-319 000), reported using MAUD. Among the 7.9 million adults with past-year alcohol dependence, 2.7% (95% CI, 1.6-3.8) reported using MAUD.

Among adults with past-year AUD, compared with those with no alcohol use treatment, using MAUD was associated with residing in large metropolitan areas (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 6.2; 95% CI, 1.6-24.0), frequent ED visits (3 or more times; AOR, 6.6; 95% CI, 1.7-25.5), alcohol dependence (AOR, 16.1; 95% CI, 1.8-149.2), and receiving mental health care (AOR, 10.6; 95% CI, 3.1-35.9) (Table). Compared with receiving nonmedication alcohol use treatment, receiving MAUD was associated with residing in large metropolitan areas (AOR, 5.9; 95% CI, 1.3-26.2), frequent ED visits (3 or more times; AOR, 8.9; 95% CI, 2.0-38.6), and receiving mental health care (AOR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.2-15.8). Receiving nonmedication alcohol use treatment was associated with having an ED visit (AOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1-3.2), alcohol dependence (AOR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.4-4.9), receiving mental health care treatment (AOR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.6-3.9), and having illicit drug use disorder (AOR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.7-4.6).

Table. Multivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression Results Among 3107 US Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder

Discussion

Although guidelines suggest that patients with AUD should be prescribed MAUD and brief counseling as initial therapy or referred for more intensive psychosocial interventions,3,4 we found that among an estimated 14.1 million adults with past-year AUD in 2019, only 1.6% (or 223 000 persons) used MAUD. Thus, despite the availability of medications with demonstrated efficacy, MAUDs are rarely prescribed to and used by adults with AUD.

Use of MAUD may be associated with greater AUD severity. Adults receiving MAUD were more likely to report receiving mental health care and having more frequent ED visits, consistent with the associations of cooccurring psychiatric and medical disorders with greater AUD severity.5,6 Adults with AUD who receive mental health care or ED services or who reside in large metropolitan areas may have greater access to MAUD. For those receiving nonmedication alcohol use treatment, using MAUD may improve treatment effectiveness. Although NSDUH is subject to recall and social-desirability biases, our results highlight the urgent need for improving access to and use of MAUD among adults with AUD.