Abstract

A wealth of research demonstrates that harm reduction interventions for substance use (SU) save lives and reduce risk for serious infectious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis C, and other SU-related health conditions. The U.S. has adopted several harm reduction interventions at federal and state levels to combat SU-related harm. While several policy changes on the federal and state levels decriminalized interventions and further support their use, other policies limit the reach of these interventions by delaying or restricting care, leaving access to life-saving interventions inconsistent across the U.S. Federal and state policies in the U.S. that restrict access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), criminalize possession of drug paraphernalia, prevent syringe service programs and overdose prevention centers from operating, and limit prescribing of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) pose significant barriers to harm reduction access and implementation. This paper aims to bridge publications and reports on current state and federal harm reduction intervention policies and discuss policy recommendations. Federally, the DEA and SAMHSA should expand certification for methadone dispensing to settings beyond dedicated opioid treatment programs and non-OTP prescribers. Congress can decriminalize items currently categorized as paraphernalia, permit purchasing of syringes and all drug checking equipment using federal funds, amend the Controlled Substances Act to allow for expansion of overdose prevention centers, protect Medicaid coverage of PrEP, and expand Medicaid to cover residential SU treatment. At the state level, states can reduce regulations for prescribing MOUD and PrEP, decriminalize drug paraphernalia, codify Good Samaritan laws, and remove restrictions for syringe service program and overdose prevention center implementation. Lastly, states should expand Medicaid to allow broader access to treatment for SU and oppose Medicaid lock-outs based on current SU. These changes are needed as overdose deaths and serious infectious disease rates from SU continue to climb and impact American lives.

The severity of substance use morbidity and mortality in the U.S.

In 2023, 48.5 million Americans aged 12 or older met criteria for a substance use disorder, including both alcohol and drug use disorders. Additionally, fatal drug overdose is a leading cause of injury-related death in the U.S.. Over 105,000 substance use-related deaths occurred in 2023 alone, a 307% increase over the last 20 years. Additionally, over 65.9% of people who died in 2023 from an overdose had at least one potential opportunity for intervention, defined as a potential bystander physically nearby before or during the overdose, past substance use treatment, witnessing a fatal drug overdose, a mental health diagnosis, a prior overdose, or recent release from a correctional institution or inpatient substance use or mental health facility. Racial disparities in overdose deaths have emerged in recent years, with 2022 data showing overdose death rates declining among White Americans and increasing for all other racial and ethnic groups. Disparities in overdose deaths are most pronounced among Black Americans and Native Americans, reaching 1.4 times and 1.8 times the rate of White Americans, respectively. Unfortunately, overdose deaths among sexual and gender minority (SGM) adults is relatively less-studied, with a recent systematic review calling for more research after finding only one study from 2001 investigating overdose mortality in SGM populations. Others have found that while mortality is less studied, SGM adults are more likely than cisgender and heterosexual adults to use both prescription and illicit opioids, suggesting a potential unstudied disparity in overdose deaths. More research examining risk factors for fatal overdoses is needed, and future research should specifically investigate overdose risk and fatalities among individuals across multiple racial and sexual and gender identities.

Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, is the current driver of overdose deaths, with over 75.2% of overdose deaths involving fentanyl in 2023. Fentanyl has been increasingly present in other opioid-based and non-opioid illicit substances (e.g., stimulants) since 2013, causing unintentional use by persons who are unaware of fentanyl adulteration in their drug supply. While much of the focus of public policy has centered around opioid overdose prevention, methamphetamine and cocaine overdose deaths are rapidly increasing each year independent of the presence of fentanyl, increasing 317% from 2013 to 2019. Additionally, xylazine, a veterinary sedative, is also adulterated in the illicit drug supply, and death rates involving xylazine continue to increase each year. A recent analysis utilizing methods by a 2017 CDC study estimated a total economic cost of the opioid epidemic at $2.7 trillion in 2023, with $1.1 trillion (41%) from opioid overdose deaths, $1.34 trillion (39%) lost in quality of life, and $277 billion (10%) from healthcare costs, labor productivity, and criminal legal system-related costs.

Injection drug use rates have risen in the past ten years, with current estimates indicating that 3.6 million adults injected drugs within the last year. Many people who inject drugs report sharing needles or drug injection equipment with others, putting themselves and those they share needles with at high risk for hepatitis C (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Increased injection drug use has led to an increase in serious infectious disease rates, being referred to as a dual epidemic by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. HCV infections have increased 124% between 2013 and 2020 after decades of a steady decline in new cases, largely due to the increase in injection opioid use. The economic burden of HCV infections in the U.S. is estimated at $10 billion per year from direct medical costs, reduced quality of life, and work productivity.

While HIV infection rates in the U.S. remain stable (i.e., between 37,000 to 40,000 new infections each year), HIV infection rates specifically among people who inject drugs have increased. A 2018 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examining HIV risk behaviors among people who inject drugs reported that one in three injection drug users reported using a syringe in the past year that had been used by someone else. In 2020, one in fifteen people who acquired HIV acquired it through injection drug use. During this time, uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV transmission remains low among persons who inject drugs. Lifetime HIV-related medical costs are estimated at $420,285 in direct medical costs and $120,000 in loss of productivity per HIV infection. Lastly, hospitalizations for severe injection-related infections have increased, including infective endocarditis, sepsis, bone and joint infections, and skin and soft-tissue infections. While national monitoring of this increase has been limited, a 2018 study using public health data sources estimated that there were 98,000 hospital visits due to serious injection-related infections a yea.

Frameworks to address substance use problems

There are two prevalent substance use treatment approaches within public policy: abstinence-only and harm reduction. The abstinence-only model aims for sustained cessation of all substance use. An underlying belief of the abstinence-only model, particularly pronounced within the U.S., is that drug use is morally wrong and therefore, people who use substances should be punished. This belief is reflected in current U.S. criminal legal policy which criminalizes substance use at both the federal and state level. The abstinence-only model has been the primary model utilized within substance use treatment settings and historically has been framed within policy and practice as the only appropriate approach to address individual and societal substance use in the U.S.. Data from substance use treatment providers indicate that often abstinence-only group (e.g., 12-step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous/Narcotics Anonymous) attendance is required and acceptance of non-abstinence goals from providers remains low for illicit drug use.

Alternatively, a harm reduction approach moves away from abstinence as the primary goal, acknowledging that people may not desire total abstinence from substances. A harm reduction approach aligns with research that demonstrates that incremental behavioral changes are more sustainable over time. The harm reduction model centers the people who use substances as experts in what positive change may look like, with the goal of improving health and wellbeing overall. Many harm reduction interventions achieve this by focusing on minimizing negative consequences of substance use such as overdose, serious injection-related infections, employment issues, and interpersonal conflict.

Harm reduction approaches are needed for several reasons. First, people who use substances may be interested in treatment, but have different recovery goals than total abstinence, such as reducing their use, engaging in safer use behaviors (e.g., stopping injection use or syringe sharing), and increasing their self-efficacy and social support. Because abstinence-only programs require a commitment to total abstinence, substance use treatment has traditionally been accessible to only a small number of people. Second, the harm reduction approach has been shown to prevent a return to use. Returning to substance use post-treatment and returning to treatment are both common occurrences, regardless of substance use goals. The abstinence-only model pathologizes any return to use as a recovery failure, which often results in feelings of guilt, self-blame, and a perceived loss of control. These feelings have been shown to increase the likelihood that an individual will disengage from treatment or engage in prolonged use. Common treatment policies enforce this further by requiring abstinence and terminating persons from care who test positive for substances, potentially increasing harm during a critical time point when more recovery support is needed. In sum, harm reduction allows for flexibility in what recovery looks like, incorporates the individual’s values and goals, and focuses on areas of functioning impacted by substance use identified by the individual, all of which show efficacy in sustaining long-term behavioral changes and improved well-being. These strengths of the harm reduction approach are missing from the abstinence-only model.

The efficacy of harm reduction interventions (HRIs) for illicit substance use, U.S. policy, and barriers to HRI expansion

Federal and state public policy have shifted over time to recognize harm reduction interventions (HRIs) as evidence-based practices and support expansion of these efforts as a key component of opioid use and overdose strategy plans. Many of these approaches were first conceptualized and piloted by people who use substances in response to government inaction on these issues, often risking potential legal problems. Despite the current legal and public health shift, federal and state HRI policies vary significantly, creating a patchwork of accessible HRI interventions across the US. Naloxone, PrEP, and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD; e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone) are all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), so people who use drugs can legally access them in any state. However, federal and state regulations involving prescribing and receipt of medications such as methadone and buprenorphine create significant access barriers. The legality of other HRIs such as syringe service programs, overdose prevention centers, and drug checking equipment vary by state and have complex nuances making the legality of utilizing these services and obtaining these supplies unclear.

Harm reduction-related substance use treatment

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD)

Efficacy of MOUD

There are several FDA-approved MOUD which function by alleviating withdrawal symptoms and blocking the agonist effects of other opioids. Opioid agonist medications such as methadone (full-agonist) and buprenorphine (partial-agonist) are considered the gold-standard treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD). Both methadone and buprenorphine have substantial evidence demonstrating reductions in returning to opioid use and overdose rates, as well as increased treatment retention and quality of life. Naltrexone, an injectable opioid antagonist, is used to treat both opioid and alcohol use disorders. A systematic review on the use of naltrexone for OUD concluded that naltrexone reduces opioid use and rates of return to use, although more studies are needed. High rates of attrition before and after naltrexone administration are common, in part because naltrexone is an antagonist medication that requires opioid detoxification and withdrawal before initiating naltrexone treatment. Additionally, an important limitation of extended-release naltrexone injection is that patients develop decreased opioid tolerance and risk potentially fatal overdose, if they return to non-medical opioid use after discontinuing naltrexone or if they try to overcome the naltrexone opioid blockade.

To further illustrate, studies have shown no significant reduction in overdose risk for individuals taking naltrexone compared to non-medicated controls, while others have shown that naltrexone treatment is associated with lower fatal opioid overdoses and similar non-fatal overdoses compared to treatment with other medications . Future research needs to address barriers to treatment initiation and completion to better determine the effectiveness of naltrexone for opioid use. All MOUD are associated with a reduction in HCV and HIV infections through reductions in injection-related and sex-related risk behaviors, in addition to increased adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy and an increased probability of viral suppression. Research on the cost effectiveness of MOUD measured by mortality, quality of life-adjusted years, and medical and criminal legal system costs indicates that compared to no treatment, lifetime cost savings per person were $100,000 for methadone, $60,000 for buprenorphine, and $40,000 for naltrexone.

Current federal and state policies regarding MOUD

While MOUD are legal to obtain, there are several policies that regulate prescribing and dispensing methadone and buprenorphine. For buprenorphine, prescribers were federally required to apply for a waiver on their Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) license (e.g., the X-Waiver), complete additional training, and had limits on the number of patients they could prescribe the medication to until December 2022. Now, prescribers are not required to obtain an X-Waiver, meaning any practitioner with Schedule-III prescriptive authority can prescribe buprenorphine. However, while federal regulations have shifted to remove barriers to buprenorphine, policies in several states further regulate buprenorphine and restrict access. As of September 2024, twelve states currently include outdated X-waiver provisions in existing buprenorphine prescribing policies. Additionally, several states include restrictions beyond federal requirements which limit patients’ ability to obtain buprenorphine such as visit frequency requirements, mandated counseling (including length and number of sessions), restrictions on the format or content of the counseling, additional drug testing beyond federal requirements, noncompliance policies, and restrictive dosing regulations.

Methadone, in contrast, can only be prescribed by certified providers within federally certified clinics referred to as opioid treatment programs, where the medication must also be dispensed. While methadone cannot be filled in the pharmacy for persons with opioid use disorder, methadone can be filled at the pharmacy when prescribed for pain management. This practice is not common in countries other than the U.S. where methadone can be dispensed at a pharmacy for opioid use disorder or pain. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recently finalized rules enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic that allow up to 7 days of take-home doses of methadone during the first 2 weeks of treatment, 28 days of take-home doses of methadone for patients following one month of treatment, removed counseling prerequisites, and allowed initiation of methadone treatment via telehealth if video is used.

Several states go beyond federal methadone requirements by stipulating new centers file a certificate of need to open a new facility; additionally, Indiana has a limit on the number of facilities in the state, and Wyoming has a moratorium on opening new facilities. Other facility-related barriers include obtaining a pharmacy license or registration, pharmacy regulation adherence, pharmacist service requirements, and state zoning restrictions. Further, several policies impose burdens on patients including daily attendance in clinic for dosing of methadone and engagement in a behavioral treatment program, making it difficult to maintain employment or other responsibilities. These treatment requirements are more restrictive than prescribing full-agonist opioid medications like morphine or oxycodone. Other barriers to receipt of methadone across states include requiring specific frequencies of patient visits, mandated counseling (including length and number of sessions), restrictions on the format or content of the counseling (e.g., restrictions on telehealth), restrictive criteria beyond federal requirements for take-home doses, prohibiting and/or requiring special authorization for specific dosage levels, and requirements for additional urine drug screenings beyond federal requirements. Finally, restrictive policies from Medicaid may also require prior authorization or the failure of other pharmaceutical interventions in order for patients to qualify for methadone treatment, further impeding the ability of both patients and providers to access these medications.

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for MOUD

While methadone and buprenorphine are considered gold-standard treatments due to the longstanding evidence of their impact on mortality, nonfatal overdose, treatment retention, and quality of life, several policies remain that create barriers to the distribution of these medications. Federally, the restriction of methadone dispensing to opioid treatment centers, which require daily clinic attendance, limits access significantly and is a stark contrast to patients with chronic pain who can receive methadone through their pharmacy. At the state level, policy barriers for methadone also remain on the opioid treatment center level, such as additional certifications to open an opioid treatment center, pharmacy-related regulations (e.g., obtaining a pharmacy license or registration, pharmacy regulation adherence, pharmacist service requirements), and zoning restrictions. State policies for both methadone and buprenorphine that impact patients directly include visit frequency requirements, mandated counseling (i.e., length and number of sessions), format- or content-related restrictions for counseling, additional drug testing beyond federal requirements, noncompliance policies, and restrictive dosing regulations. Specifically for methadone, state policies also place additional restrictions beyond federal requirements on take-home doses.

Federally, the government should expand methadone dispensing to settings other than specific opioid treatment programs such as pharmacies and expand prescribing to office-based addiction specialists, primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. This will allow for broader access to an efficacious treatment modality, potentially increasing uptake of treatment and reducing burden on the healthcare system. If this recommended change is made, Medicaid Part D policy should be revised to include coverage of methadone dispensed by pharmacies. Currently, Medicare Part D does not cover methadone dispensed in pharmacies to treat opioid use disorder, but does cover methadone dispensed in pharmacies for pain.

Additionally, state policies on restrictions for buprenorphine and methadone should be amended to align with federal policy by removing requirements shown to create barriers for access to medications for opioid use disorder (e.g., frequency of visits, mandated counseling, format or content-related restrictions for counseling, dosage limits, additional urine drug screenings, non-compliance policies) and the operations of opioid treatment programs (e.g., state certifications, zoning laws, additional pharmacy regulations).

Overdose prevention harm reduction interventions

Drug checking equipment and services

Efficacy of drug checking equipment and services

Fentanyl test strips, originally developed to detect fentanyl in urine samples as part of urinalyses, are now available over-the-counter in some states as a type of drug checking equipment to identify the presence of fentanyl in one’s drug supply. Recent studies show that use of fentanyl test strips reduced frequency of illicit opioid use, solitary drug use, and frequency of drug injection among persons at high risk for opioid overdose, such as sex workers who use opioids and people who inject drugs. Xylazine, a sedative with anesthetic properties used in veterinary settings, has recently appeared in the drug supply and has been implicated in overdose deaths across the U.S.. Recent testing of newly developed xylazine test strips has demonstrated that they are acceptable in detecting xylazine in drug samples and are now available for purchase in some states. Qualitative research has shown that people who use drugs are concerned about undesired exposure to xylazine and are interested in using xylazine test strips. Now that xylazine test strips are available for purchase online and in-person in some states, research examining the impact of xylazine test strips on behavioral outcomes is needed. Additionally, future research should evaluate the cost savings of utilizing test strips in relation to substance use and overdose outcomes.

While test strips offer a low-cost option for detecting substances present in illicit drugs, more sophisticated drug testing services from harm reduction agencies are increasingly being offered in the U.S. using onsite testing technologies such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, reagent testing, Raman spectroscopy, fentanyl immunoassay test strips, and paper spray mass spectrometry. Several sites also offer confirmatory offsite testing using mass spectrometry technology (e.g., gas or liquid chromatography), high performance liquid chromatography, reagent testing, and nuclear magnetic resonance. In addition to informing persons who use drugs about their supply, some programs offering drug testing services have also partnered with government public health entities utilizing data collected to inform broader communication to persons in the community about new substances detected. More information on organizations in the U.S. providing drug checking services can be found in Park and colleagues’ survey. As programs continue to pilot drug testing services, research on their impact on substance use and overdose outcomes are needed.

Current federal and state policies regarding drug checking equipment

Federal policy on drug paraphernalia does not explicitly list drug testing equipment as an example of paraphernalia, making it likely that possession is not prohibited on the federal level. In 2023, Senate Bill S.2484, Expanding Nationwide Access to Test Strips Act, was introduced in the Senate to clarify this issue by excluding drug checking equipment broadly from the federal drug paraphernalia statute. It was then referred to the Committee on the Judiciary where it remained unresolved until the end of the Senate term in 2024. Similarly, the House of Representatives Bill H.R.3563, STRIP Act, was introduced in 2023 and exempts the possession, sale, and purchase of fentanyl-specific drug testing equipment from criminal penalties. It was referred to the Subcommittee on Health under the Committee on Energy and Commerce. Now that the 119 th Congress has convened, a new bill would have to be introduced in the House of Representatives or the Senate. Federal funds from the CDC and SAMHSA can be used to purchase fentanyl test strips as of 2021.

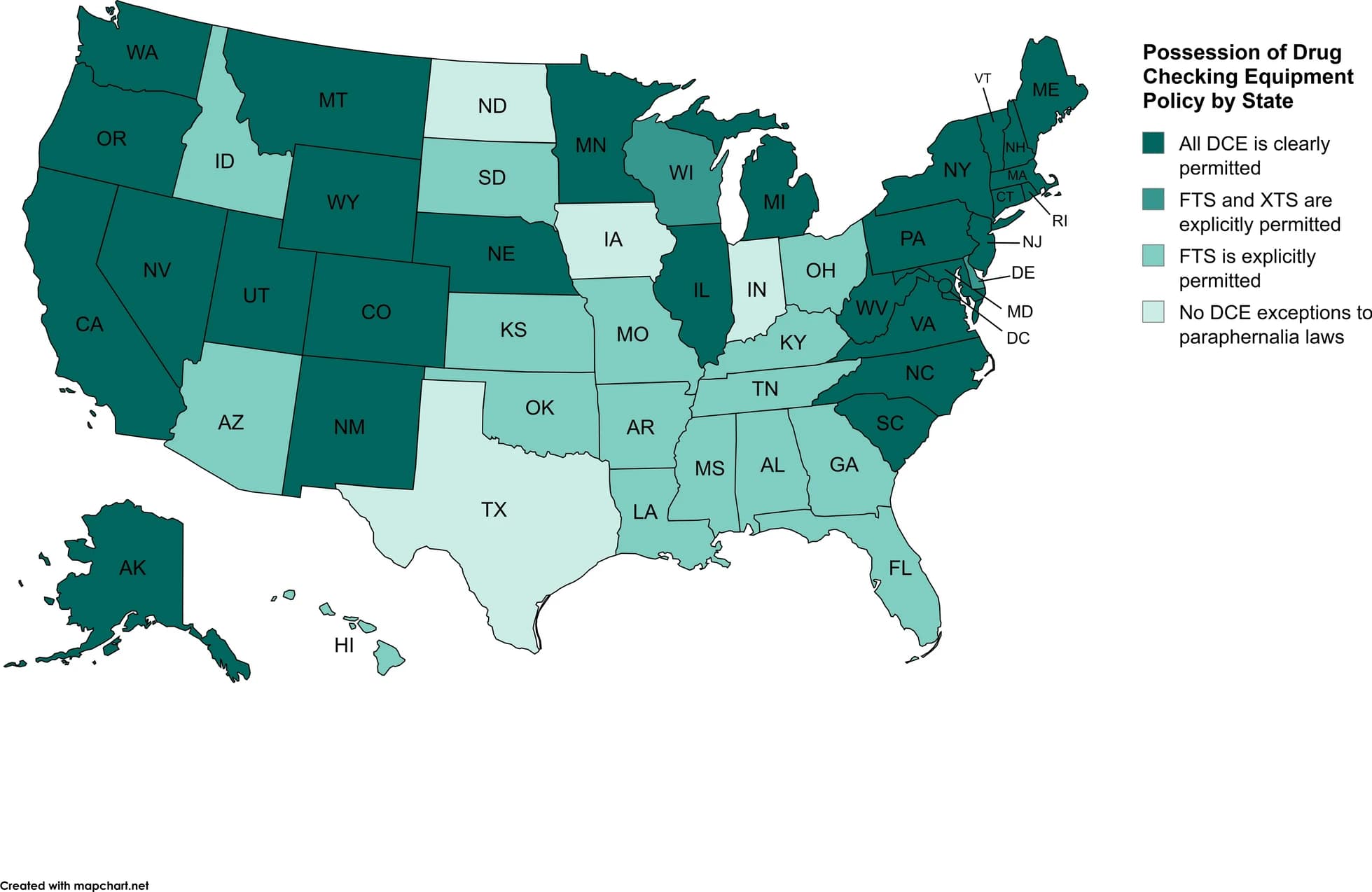

State laws regarding the possession of fentanyl and xylazine test strips vary (see Fig. 1). Possession of drug paraphernalia is a criminal offense in most states, which often includes drug checking equipment in the definition of drug paraphernalia. However, due to the rapid increase in fentanyl-related overdose deaths, state governments responded by passing legislation to permit the possession of fentanyl test strips. A total of 44 states and Washington D.C. clearly permit the possession of fentanyl test strips and, in response to xylazine-related overdose trends, two states explicitly permitted xylazine test strips, making possession of xylazine test strips legal in a total of 30 states. Specific policies related to drug checking equipment are nuanced, with 28 states and Washington D.C. explicitly excluding all drug checking equipment from drug paraphernalia laws, while 18 states provide specific drug paraphernalia exemptions to test strips or equipment meant to detect specific substances such as fentanyl, synthetic opioids broadly, xylazine, and/or other specific drugs. In the 4 states where fentanyl or xylazine test strips are not explicitly permitted (e.g., Indiana, Iowa, Texas, and North Dakota), drug testing equipment is included in their drug paraphernalia laws and possession is most likely a criminal offense.

Fig. 1 Possession of Drug Checking Equipment Policy by State as of August 2024

Other state policies regarding possession of drug checking equipment include exemptions for participants and/or staff of syringe service programs, protection against charges for drug checking equipment under Good Samaritan laws, and policies regarding free distribution of drug checking equipment. Most states have enacted Good Samaritan laws which protect persons who overdose and/or witnesses of overdoses from criminal liability for possession of controlled substances or drug paraphernalia when seeking medical assistance during an overdose. Currently, 39 states and the District of Columbia cover drug checking equipment under their current Good Samaritan laws. Due to the nuance of drug checking equipment exemptions related to staff and participants of syringe service programs, it is recommended that interested individuals refer to The Network for Public Health Law’s fact sheet, which is updated each August.

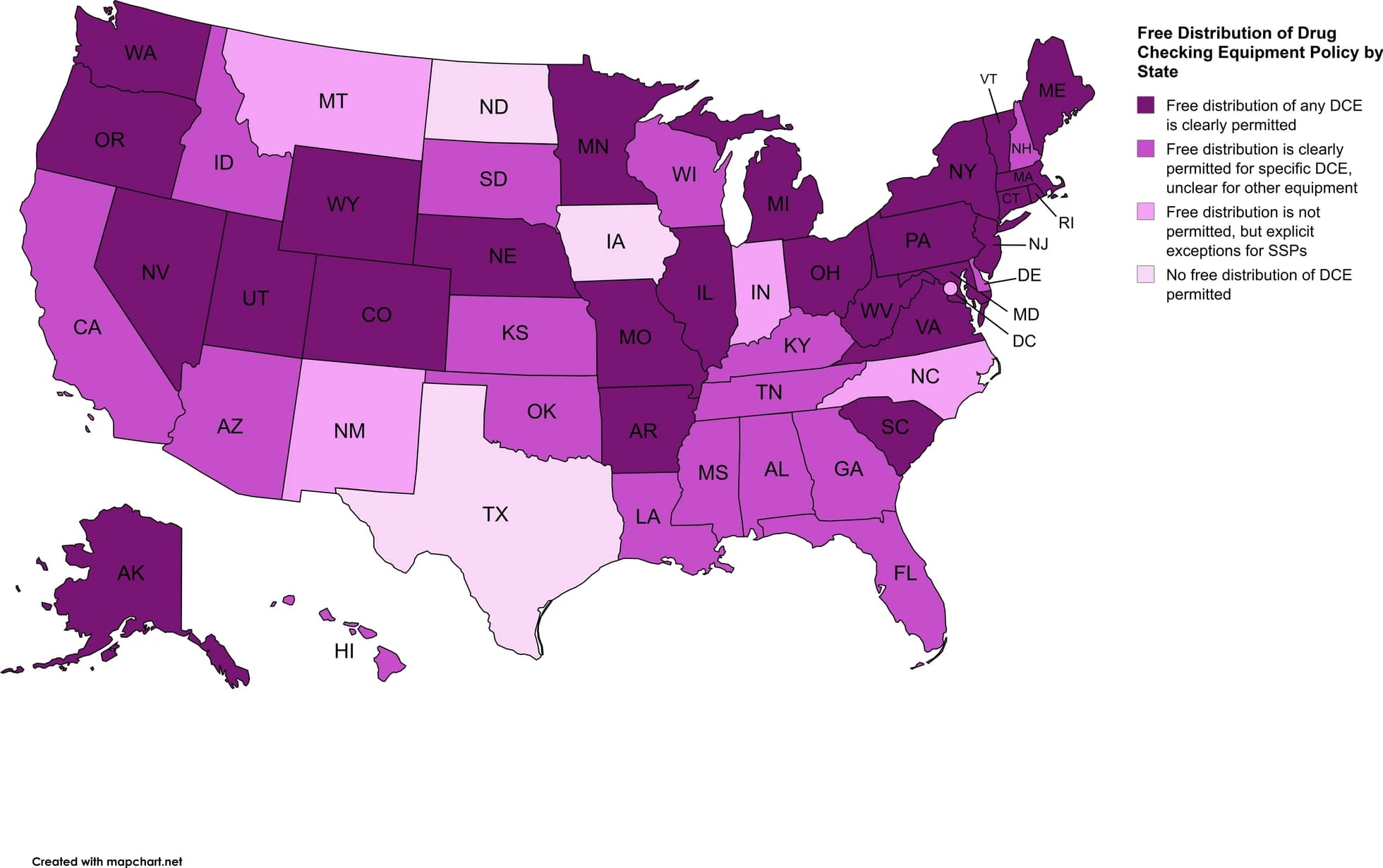

Policies regarding free distribution of test strips varies by state as well (see Fig. 2). As of August 2024, 26 states permit free distribution of any drug checking equipment, 17 states limit free distribution to specific equipment, 4 states and Washington D.C. generally do not permit free distribution of drug checking equipment clearly but have explicit exceptions for syringe service programs, and 3 states do not permit free distribution (2 of these states do not authorize syringe service programs generally, so no exceptions would exist). Examining policies regarding free distribution in context of the legality of drug checking equipment shows inconsistency state-to-state. For example, California permits possession of any drug checking equipment, but free distribution is limited to equipment specific to fentanyl, ketamine, and gamma hydroxybutyric acid. Alternatively, Arkansas permits possession of fentanyl test strips only, but free distribution of any drug checking equipment is permitted. The Network for Public Health Law states that lack of clear legalization of possession and free distribution of drug checking equipment does not equate to those activities being illegal, pointing out the free distribution of drug checking equipment via public health entities in states where it is not clearly legal to do so. They recommend modifying or repealing current laws for clarity regarding criminalization. Overall, this demonstrates the complex and sometimes confusing nature of drug policies in the U.S. as states grapple with the rapid rise of overdose deaths due to fentanyl and other adulterating substances.

Fig. 2 Free Distribution of Drug Checking Equipment Policy by State as of August 2024

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for drug checking equipment

While it is promising that most states now permit fentanyl test strips to prevent further harm from overdose deaths, several states provide exemptions of particular equipment, the source of the equipment, or the context in which the equipment is used rather than providing exemptions for drug checking equipment broadly. New legislation providing additional exceptions to specific drug testing equipment would need to be passed in response to emerging trends in drug adulterants and overdoses. Overdose deaths involving fentanyl started to increase in 2013 and accounted for over 67.8% of total overdose deaths by 2017, but most state legislative responses followed 4 to 6 years later. Additionally, while several states explicitly permit free distribution of specific drug checking equipment (e.g., fentanyl test strips), distribution of other drug checking equipment (e.g., xylazine test strips) remains unclear. Providing exemptions for certain equipment and/or entities who can distribute it, rather than legalizing the equipment broadly, limits the ability for people to use the equipment to reduce risk from unintentional overdoses involving adulterated substances. Considering the rapid proliferation of trends in overdoses and the lengthy legislative process, broad changes are needed.

The federal drug paraphernalia statute (i.e., 21 U.S. Code § 863) and individual state statutes include devices used for smoking or inhaling drugs as paraphernalia, despite evidence that these practices are safer than injecting substances in context of preventing the spread of infections (i.e., HIV, hepatitis). Decriminalizing all drug paraphernalia federally would prevent legal concerns about possessing syringes, clarify that drug checking equipment possession is legal, and smoking and inhaling-related devices and may reduce harm. Additionally, federal policies allowing the use of federal funds to purchase fentanyl test strips should be expanded to all drug checking equipment. States should also consider repealing drug paraphernalia laws and decriminalizing the possession, distribution, and sale of items currently considered as drug paraphernalia (e.g., syringes, drug testing equipment, smoking and inhalant devices) to reduce barriers to evidence-based harm reduction interventions. At minimum, state paraphernalia laws should exclude drug checking equipment from current drug paraphernalia laws and prohibit additional restrictions on drug checking equipment from local jurisdictions. While most states have passed legislation excluding drug testing equipment to some extent (e.g. fentanyl test strips), more widespread and comprehensive policy changes are recommended, as the lengthy legislative process cannot keep up with the changing nature of overdose in the U.S. The rapid proliferation of fentanyl and xylazine adulteration in the drug supply within the last decade and the delayed legislative response demonstrates this. Excluding drug checking equipment broadly allows for swift reduction of harm. To this end, the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association provides a guide for state policymakers to introduce legislation authorizing possession, distribution, and sale of drug checking equipment, allow state funds for these activities, and prohibit local jurisdictions from passing policies in conflict with state legislation.

Naloxone

Efficacy of naloxone

Naloxone is a medication that can rapidly reverse opioid overdose-induced respiratory depression and death from secondary cardiac arrest. It is available in the U.S. as a nasal spray and as an injectable medication. While primarily administered by trained medical professionals since its development in 1970, overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs have been developed to distribute naloxone and provide training on overdose prevention, recognition, and responses to laypersons who may witness an opioid overdose. An umbrella review of systematic reviews concluded that OEND programs effectively reduce opioid overdose-related deaths. Cost-effectiveness analyses examining naloxone distribution to laypersons and first responders resulted in savings of $15,950 per quality-adjusted life years gained.

Current federal and state policies regarding naloxone

Historically, naloxone was only available by persons at risk for overdose requesting the medication from their medical provider, due to requirements that prescribers must have examined, diagnosed, or treated the person the medication is being prescribed for. By 2017, all states passed policies to provide greater access to naloxone through third-party prescribing, in which anyone who may be a potential bystander can request naloxone from prescribers, or standing orders, in which pharmacists can dispense naloxone directly to the public. While naloxone is still available through standing orders, prescriptions from providers, and community distribution, the FDA has since approved the nasal spray version of naloxone for over-the-counter purchase, removing a critical policy barrier to access. The nasal spray for naloxone is currently covered by Medicaid and is on the Medicaid preferred drug list, which encourages the prescription of several drugs, in 38 states as of 2024. However, more research is needed to determine access to naloxone at local pharmacies, as previous data suggests many pharmacies do not have naloxone in stock.

As stated above, Good Samaritan laws protect people who overdose and/or witnesses an overdose from legal consequences when seeking or providing emergency services. As of April 2024, all states but Kansas and Wyoming have Good Samaritan laws, most of which were passed in 2015 or later. However, state laws vary by who they protect (e.g., a witness versus the person experiencing the overdose), what potential crimes they protect against (e.g., low-level drug offenses, possession of paraphernalia), and the stage of the criminal legal process (e.g., arrest, prosecution, or providing an affirmative defense of an allegation during court proceedings). In a small number of states (Alabama, Indiana, Maine, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin), only the witness seeking assistance is provided protection against legal consequences. Additionally, in 25 states and the District of Columbia, protection against arrest and prosecution is provided for low-level drug offenses, whereas the policies in remaining states that have Good Samaritan laws only provide protection against prosecution for this crime. All but two states (Arkansas and South Dakota) provide protection against possession of drug paraphernalia charges under Good Samaritan laws by explicit legal protection or due to policies generally allowing possession of paraphernalia if there is no intent to sell it. Other policies pertaining to the conditions of Good Samaritan laws can be found in Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association’s review.

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for naloxone

While several barriers to naloxone have been removed (e.g., prescriber abilities, over-the-counter access, Medicaid coverage), barriers on the state level remain concerning Good Samaritan laws. The remaining states which have not codified Good Samaritan laws should enact this policy to ensure rapid overdose responses. Currently, in states which have Good Samaritan laws, the variability in protection against legal consequences prevents these laws from successfully accomplishing what they were enacted for, which is to prioritize the personal safety of the person overdosing by removing concerns of legal consequences. Therefore, states should amend their policies to ensure both witnesses and people experiencing an overdose are protected at the earliest stage (e.g., arrest) from low-level drug offenses and possession of drug paraphernalia.

Overdose prevention centers (OPCs)

Efficacy of OPCs

Overdose prevention centers (OPCs), also known as supervised injection sites or safe injection facilities, are another harm reduction approach to preventing overdose. OPCs are facilities in which people can use drugs under medical supervision to reduce overdose risk while removing fear of criminal prosecution. OPCs aim to reduce infectious disease transmission by providing sterile injection devices, safe disposal of injection devices, screening for infections and diseases, and connect persons to treatment through referrals to health and substance use services. Systematic and scoping reviews on OPCs have concluded that OPCs provide a safe environment to use drugs, reduce drug use behaviors associated with infection and disease transmission (e.g., syringe sharing), reduce risk for both fatal and non-fatal overdoses, and increase access to substance use and health-related services. OPCs also positively impact the surrounding environment by reducing public drug injections and the number of syringes left in public spaces without increasing crime in the area. OPCs have been in operation in Europe as early as 1986 and have demonstrated effectiveness. Additionally, the few OPCs open in the United States demonstrate that operating an OPC in the U.S. is feasible, saves lives (e.g., all overdoses at the facility were nonfatal), reduces emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and does not increase crime in the area. Future research examining the cost-effectiveness of overdose prevention centers in the U.S. is needed as no data was publicly available at the time of writing.

Current federal and state policies regarding OPCs

The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (Pub. L. 91–513, 84 Stat. 1236), referred to as the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. § 856), declares that it is unlawful to manage any place for the purpose of using a controlled substance. This federal policy was enacted in the 1980’s to prevent “crack houses”, where persons would purchase and use crack. Citing concerns about federal challenges, several bills on the state level authorizing OPCs have been vetoed. See the Drug Policy Alliance’s summary for the status of policies passed and being considered at the state and local levels to explicitly authorize OPCs as of December 2024.

Furthermore, enforcement of policies surrounding OPCs in the U.S. remains unclear as OPCs have opened and only one court case has been brought to the federal level to challenge their opening as of December 2024. The first OPC opened in 2014 in an undisclosed urban area of the U.S. without authorization from state or local entities. The Philadelphia city council voted in favor of opening an OPC in 2019, but halted plans after the U.S. Department of Justice declared that the opening of the facility is in violation of the Controlled Substances Act. The Third Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the U.S. Department of Justice in 2024 (United States v. Safehouse), finding that the Philadelphia OPC would violate 21 U.S.C. § 856 and stating that change can only occur if Congress amends the current policy to exclude OPCs from the statute. However, the case remains ongoing as Safehouse has filed another appeal. Most importantly, because the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, the current ruling that the Safehouse OPC cannot open only applies within the Third Circuit’s jurisdiction (e.g., Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware), leaving the larger question of whether OPCs violate U.S. federal law unanswered. More details about the status of the case as of December 2024 can be found in the brief from the Drug Policy Alliance. In 2021, the city of New York was the first city in the U.S. to authorize the opening of OPCs, and two are open as of 2024. In 2021, the state legislature of Rhode Island authorized a pilot program for OPC and opened their first OPC in December of 2024. Lastly, Vermont passed legislation in 2024 to authorize the operation of OPCs.

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for OPCs

Significant policy barriers remain on the federal and state levels that prevent the opening and operation of OPCs. On the federal level, all OPCs currently opening or operating are at risk of legal challenge by the U.S. Department of Justice under 21 U.S.C. § 856, as seen with the United States v. Safehouse case. Since that court case remains open on appeal, the legality of OPCs federally remains unclear. Some states and local jurisdictions have comparable statutes to the Controlled Substances Act, but whether state policy will be enforced is also unclear, as there have been no known OPCs that have been challenged by state or local entities. Other than Rhode Island and Vermont, which have authorized OPCs on the state level, all other states have not authorized OPCs, and some state and local governments have passed legislation explicitly banning OPCs. Federal and state policies should be amended to allow for the establishment of a nation-wide network OPCs that reduce substance use-related harm (e.g., overdoses, infectious diseases) and increase treatment initiation. Congress should repeal 21 U.S.C. § 856 to ensure OPCs can legally operate in the U.S. and ensure that state-level policies authorizing OPCs will not be federally challenged. Additionally, all states should pass legislation explicitly authorizing OPCs to operate, repeal state policies modeled after the Controlled Substances Act, and prevent local jurisdictions from enacting policies prohibiting OPCs at the local level. These recommended policy changes will remove current OPC-related policy barriers and allow for a significant opportunity for people who use substances by ensuring a safe environment that protects them from fatal overdoses and criminal legal concerns, provides crucial health-related services, and connects individuals interested in recovery with referrals to treatment.

Infection prevention harm reduction interventions

Syringe service programs (SSPs)

Efficacy of SSPs

Syringe service programs (SSPs) are community-based programs that provide access to sterile needles and syringes, safe disposal of used syringes, safer use education, health-related testing, and referrals similar to overdose prevention centers. SSPs are effective in reducing transmission of HIV and HCV, reducing injection drug use overall, and increasing the likelihood of individuals entering substance use treatment . Research on the cost-effectiveness of SSPs and other harm reduction strategies in reducing cases of HCV among persons who inject drugs found a total of $363,821 in incremental cost savings per HCV case avoided. Efforts to increase the availability of SSPs in non-urban areas is needed.

Current federal and state policies regarding SSPs

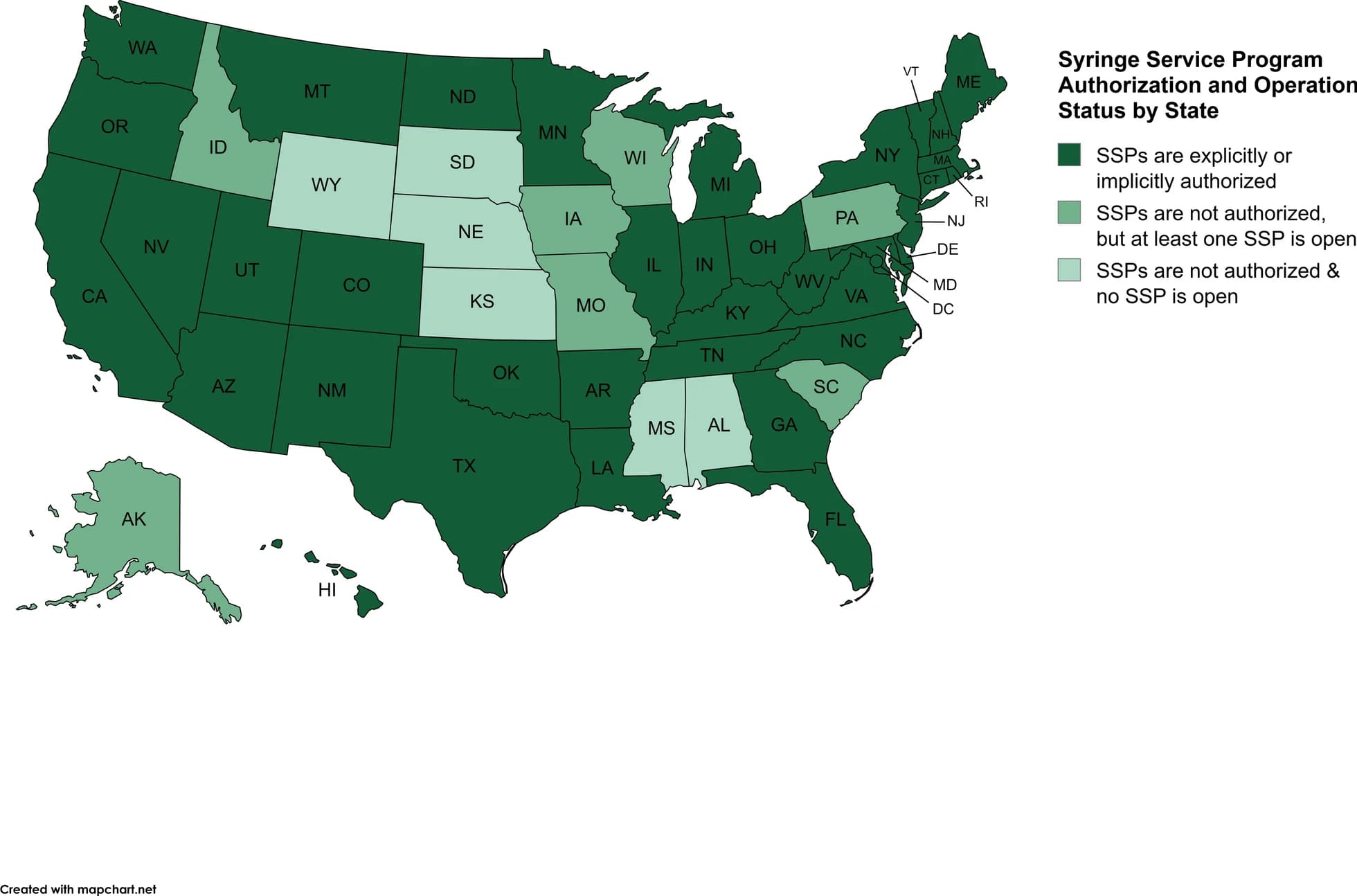

Following Congress’ lift on the total ban on the use of federal funds to support SSP activities in 2016, several federal entities now support funding of syringe service program infrastructure, training, and general operations due to the various health–related services they provide (e.g., screenings for infections and diseases, medical and substance treatment referrals). Despite federal support, policies vary on the state and local levels regarding authorization to operate, requirements to involve law enforcement in implementation, and requirements for SSP participants. SSPs are authorized implicitly or explicitly by statutes, regulations, or executive orders in 37 states and the District of Columbia. However, local jurisdictions have additional authority in 11 states by requiring authorization (California, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and West Virginia). Three of these states also permit termination of SSPs from local jurisdictions (Indiana, Kentucky, and Maryland). Seven states (i.e., Alaska, Idaho, Iowa, Missouri, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Wisconsin) that do not authorize SSPs have at least one SSP currently open that publicly acknowledges providing syringe services. Comparing policies to implementation of overdose prevention centers (described above) and SSPs, it is clear there is a difference between state policy and actual practice. Figure 3 below depicts the current status of SSP authorization and operation in each state. Currently, policies in 10 states require consultation or communication with law enforcement before an SSP is implemented (California, Colorado, Georgia, Maine, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia). The CDC recommends collaboration with law enforcement agencies.

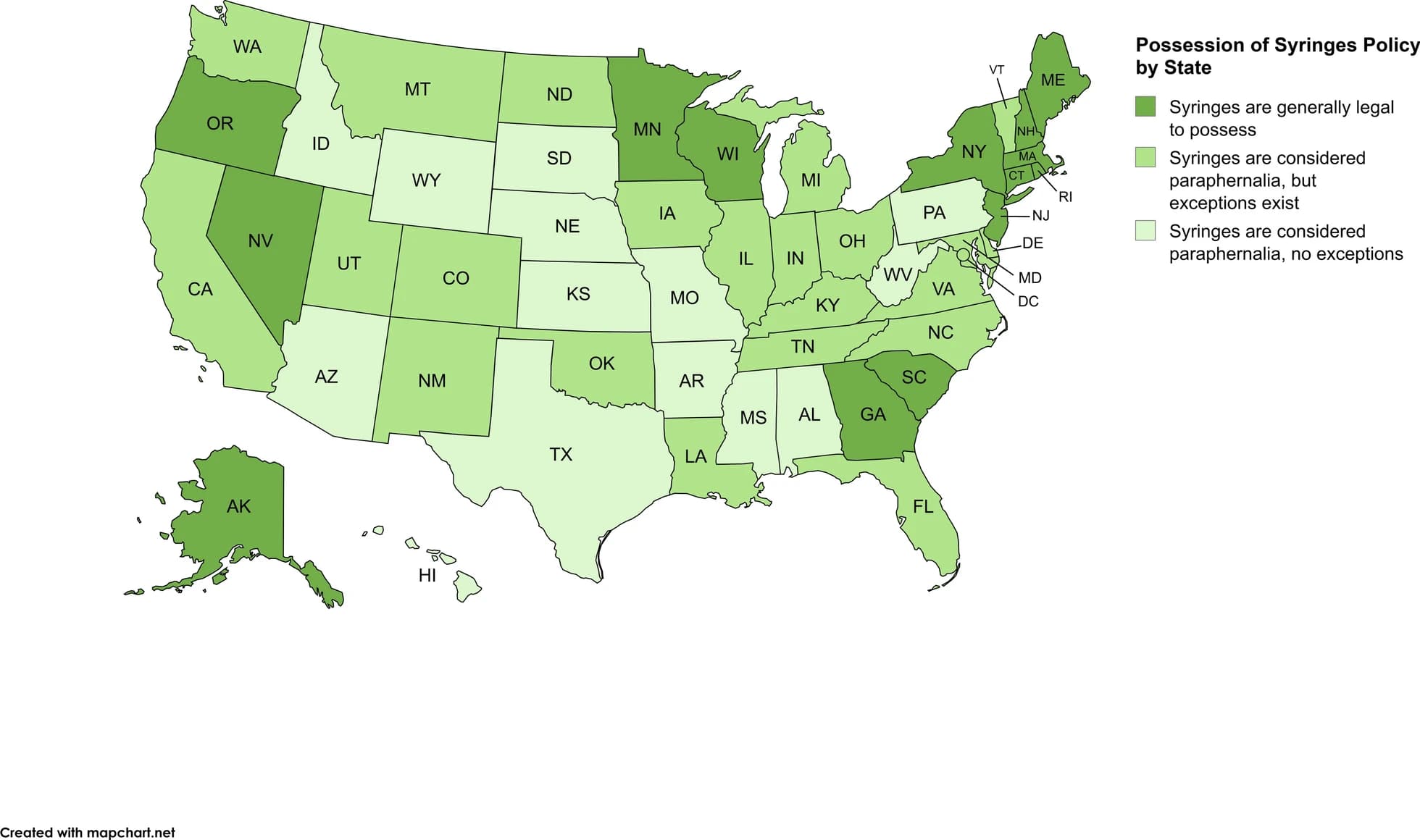

Fig. 3 Syringe Service Program Authorization and Operation Status by State as of April 2025

Policies beyond the authorization of SSPs further regulate and restrict access to SSPs. Several states restrict operations of SSPs by requiring program participants to register personal information as part of enrollment and/or specific identification for employees, volunteers, and/or participants. Additionally, syringes themselves are often considered drug paraphernalia. Federal policy on drug paraphernalia does not explicitly list syringes but defines paraphernalia in a way that describes syringes: “any equipment, product, or material of any kind which is primarily intended or designed for use in …injecting, ingesting, inhaling, or otherwise introducing into the human body a controlled substance” (21 U.S.C. 863), making federal policy on syringe possession unclear. Federal funding for SSPs cannot be used to purchase syringes themselves if funding is distributed by the Department of Labor, Health and Human Services, or Education, but can be used for other SSP-related costs, and other federal agency funds can be allocated for syringe costs. At the state level, drug paraphernalia laws include syringes in their definition in 36 states and the District of Columbia; however, 22 of these states and the District of Columbia have exceptions for persons who use drugs under specific circumstances (e.g., syringes are from SSPs, public health programs, are for disease prevention purposes, or possession is permitted when there is no intent to sell). A total of 14 states provide no exceptions for syringes under current paraphernalia laws. In the remaining 14 states, syringes are legal to possess because they are not included in current paraphernalia definitions or in rare cases the state does not have a law criminalizing paraphernalia. See Fig. 4 for the legal status of possession of syringes. Similarly, additional policies specific to syringes for SSPs include requiring the exchange of used syringes or needles in order to receive new ones and requiring syringes to be able to be traced back to the SSP they were received from. See the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association’s review for additional policies beyond authorization and possession of syringes (e.g., distribution policies for SSPs) in your state

Fig. 4 Possession of Syringes Policy by State as of April 2025

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for SSPs

Despite decades of evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of SSPs in reducing substance use-related harm through infection and disease prevention and the connection to important health and substance use treatment, federal and state policies limit the reach of SSPs. On the federal level, the remaining policy barriers are the current legal definition of drug paraphernalia that describes syringes and the inability to directly purchase syringes using federal funds. On the state level, numerous policies serve as barriers. Thirteen states do not authorize SSPs and within seven of these states, SSPs currently operating may be subject to legal challenges because there is no corresponding policy authorizing their operations. The various authorization policies (and in some cases lack thereof) are systems-level barriers which impede the swift and successful implementation of SSPs. Additionally, states that authorize SSPs have program participant requirements (e.g., registration, identification as a participant, syringe exchanges) that place an unnecessary burden on persons who inject drugs, despite CDC recommendations to provide anonymity and remove program requirements. Lastly, several state drug paraphernalia definitions include syringes. Though several policies provide exceptions for syringe possession, the burden of proof remains on the person who uses drugs to provide a defense recognized as permissible in that state (e.g., identify themselves as an SSP participant, show syringes were received from a public health entity, or demonstrate syringes are for personal use or disease prevention).

As stated in the drug checking equipment section above, Congress should amend 21 U.S.C. 863 to decriminalize possession of all drug paraphernalia, thereby explicitly permitting possession of syringes. At minimum, Congress should amend 21 U.S.C. 863 to explicitly exclude syringes from current drug paraphernalia definitions. In addition, federal funding policies should be amended to permit the purchasing of syringes directly.

States should pass legislation to authorize the operation of SSPs. All states should review and amend current policies as applicable to include the following changes: preventing local jurisdictions from restricting the opening and/or operations of SSPs locally and removing burdensome participant requirements such as registration, special identification, and used syringe exchange policies to allow anonymity and ease of access. In addition, states should decriminalize possession of drug paraphernalia, or alternatively, remaining states that criminalize possession of syringes should amend current paraphernalia laws to exclude syringes across all contexts, which would remove the need to pass policies providing exceptions for possession. These recommended changes will remove current barriers to allow persons who use drugs to engage in safer injection practices, thereby reducing harm.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

Efficacy of PrEP

PrEP is a series of oral and injectable medications that prevent HIV infection for people at risk of exposure through sex and injection drug use. When taken once daily as prescribed, oral PrEP medications are effective in reducing HIV infections between 75 to 86% among men who have sex with men and sexual partners of people living with HIV. However, a systematic review of knowledge and uptake of PrEP among persons who inject drugs demonstrates that while awareness of and willingness to use PrEP is high, uptake remains low. More research is needed to determine PrEP’s effectiveness in reducing HIV among heterosexual men and women and people who inject drugs. CDC clinical practice guidelines on PrEP identify persons who inject drugs as a priority group for PrEP receipt. Overall, the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, a U.S.-based non-governmental organization focused on promoting healthcare for HIV, hepatitis, and other transmissible diseases, estimates that increasing long-acting PrEP in addition to current oral-only PrEP would lead to a 10-year medical cost savings of over $4 billion.

Current federal and state policies regarding PrEP

Federally, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) has assigned an “A” grade to PrEP for qualifying adults and adolescents, indicating that it is a highly recommended method of preventative care. This guidance from USPSTF ensures that under current guidance, PrEP is free under almost all insurance plans, allowing for free access to medication as well as medical visits and tests needed to receive the medication. At the state level, however, some states limit access to PrEP not through insurance coverage of PrEP but through limiting the ability of advanced practice providers (APPs; e.g., nurse practitioners [NPs], physician assistants [PAs]) to prescribe the medication without the supervision of a physician through “scope of practice” recommendations. In states that limit the ability for APPs to prescribe PrEP independently, access to PrEP is necessarily limited by the supervising physician’s knowledge of and willingness to prescribe PrEP. Specifically, research has found that in states that gave APPs greater scope of practice, there were more prescriptions for PrEP written by NPs and PAs. As of 2019, 27 states had laws that allowed NPs to practice independently without restrictions, including the ability to prescribe medications like PrEP, increasing public access.

Remaining policy barriers and policy recommendations for PrEP

Federally, PrEP continues to be covered by Medicaid as the time of writing. However, a recent federal court case (Braidwood Management Inc. v. Becerra, No. 23–10,326 (5 th Cir., June 21, 2024)) is challenging the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) mandate to cover preventative care, including medications like PrEP. In June 2024, a federal appeals court ruled against the ACA coverage but, as of the current writing, only gave an exemption for preventative care coverage to the plaintiffs in the case. Portions of the case are currently under consideration by the U.S. Supreme Court, specifically questioning whether the USPSTF is legally allowed to make legally binding recommendations. If the USPSTF is found to be unconstitutionally appointed, the ruling could eliminate Medicaid coverage of many preventative care treatments, including PrEP. As a result, it is recommended that Congress take action to amend the ACA to enshrine protected coverage of preventative treatments generally and PrEP specifically.

As noted above, states that give APPs greater scope of practice to prescribe PrEP find that there are more prescriptions and greater uptake of PrEP. Therefore, it is recommended that states increase the scope of practice for APPs to include prescription of PrEP. Additionally, states can move to expand or establish state-wide assistance programs for PrEP to reduce the cost of the medication for patients, even if they do not have insurance coverage.

Expanding Medicaid to cover substance use treatment

Finally, while the scope of this paper focused on harm reduction interventions and related policy barriers, changes to Medicaid polices are needed to increase access to substance use treatment broadly and ensure coverage for persons who use substances. Expansion of Medicaid has resulted in decreased opioid-related hospitalizations in expansion states, likely due to better medical treatment and expanded access to medication (e.g., buprenorphine, PrEP). Persons who have Medicaid coverage are more likely to seek out regular care and rely less on emergency departments, lowering the burden on medical providers and the economic system as well. Additionally, state Medicaid expansion is associated with reductions in opioid overdose deaths and all-cause mortality. As of February 2025, 10 states have not adopted Medicaid expansion. All states should expand Medicaid to increase access to substance use treatment for the most vulnerable people in society. States should also oppose changes to Medicaid that may require regular drug screening or work requirements to qualify or lock individuals out of coverage due to substance use.

Second, the Institute of Mental Diseases (IMD) exclusion policy that restricts Medicaid coverage for residential substance use treatment should be amended to allow for greater patient access to comprehensive substance use care. Currently, states may apply to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for Section 1115 waivers to cover residential treatment services, and as of October 2024, IMD payment exclusion 1115 waivers have been approved across 37 states and 5 more are pending approval. Rather than force states to request exceptions to federal policy and thus give variable access to care based on the state in which a patient resides, Congress should act to allow Medicaid to broadly cover the treatment of substance use disorders across the U.S., enhancing equitable care.

Conclusion

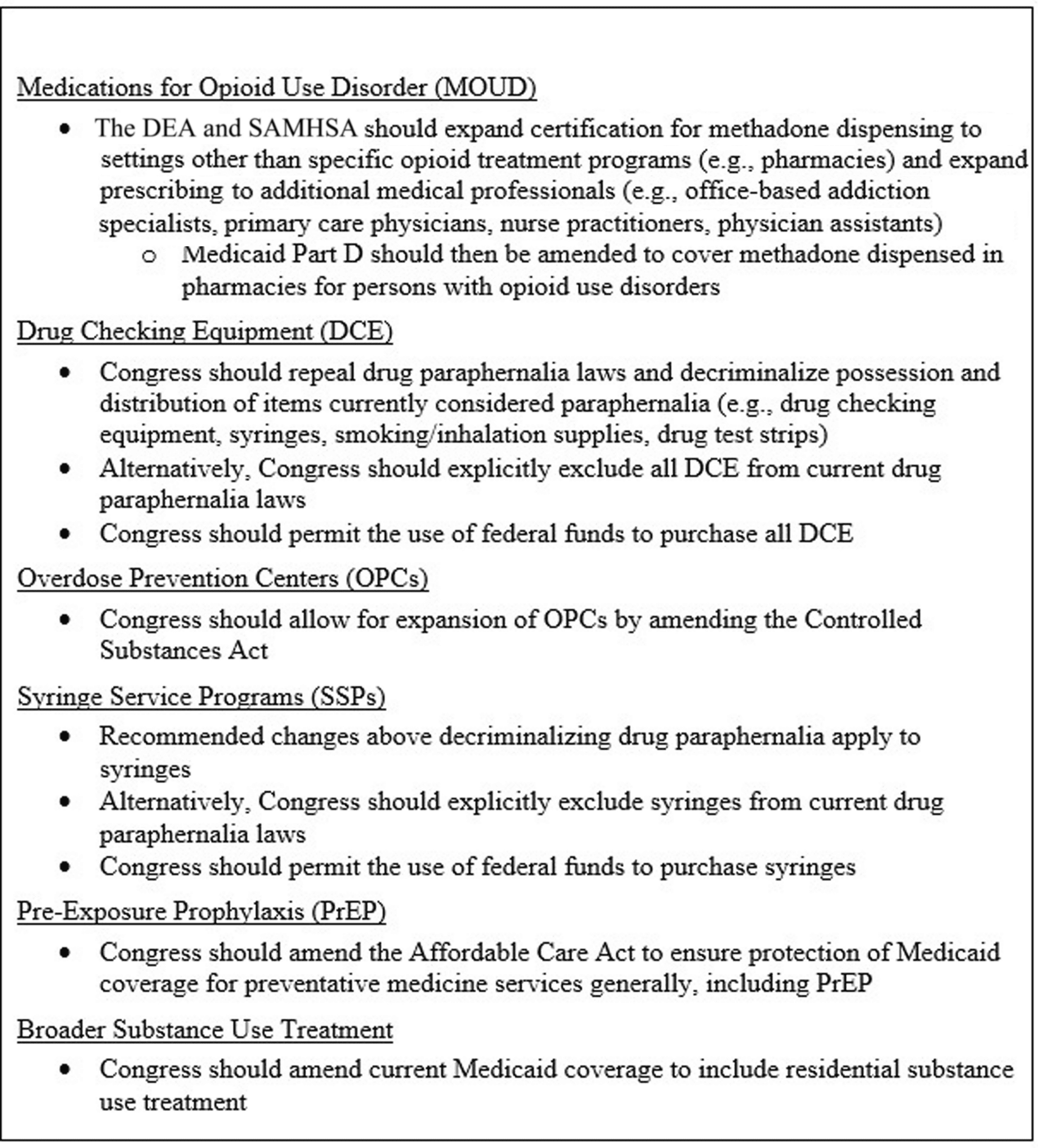

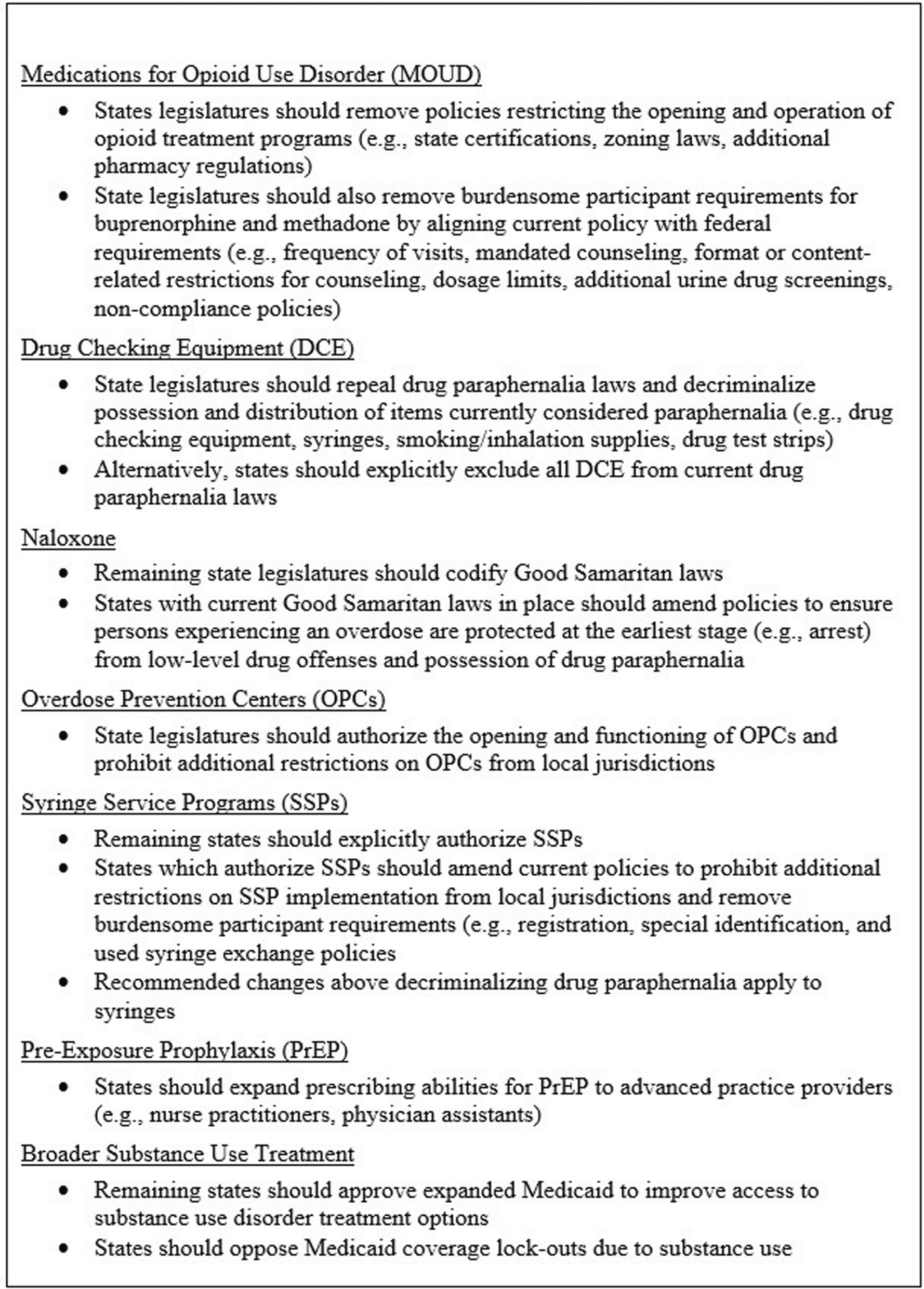

Substance use and injection drug use both pose significant health and mortality risks within the U.S. Despite readily available harmreduction and treatment options, there are significant barriers that reduce or prevent their uptake. Therefore, policy reform is recommended to remove access barriers to efficacious, lifesaving harm reduction interventions. Recommendations noted above are summarized in Figs. 5 and 6 below. In sum, while opioid and injection drug use are at the center of a public health crisis within the U.S., there are still substantive steps that both governmental officials and policy makers at the local, state, and federal levels can take to reduce substance use-related harm through evidence-based interventions and improve the physical and mental health of the population at large.

Fig. 5 Summary of Federal Policy Recommendations

Fig. 6 Summary of State Policy Recommendations

Abbreviations

ACA: Affordable Care Act

APPs: Advanced practice providers

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

DEA: Drug Enforcement Administration

DCE: Drug checking equipment

FDA: Food and Drug Administration

HCV: Hepatitis C virus

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HRIs: Harm reduction interventions

MOUD: Medications for opioid use disorder

OEND: Overdose education and naloxone distribution programs

OPC: Overdose prevention centers

PrEP: Pre-exposure prophylaxis

SGM: Sexual and gender minority

SSP: Syringe service program

SU: Substance use

SAMHSA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration

SSP: Syringe service program

USPSTF: U.S. Preventative Services Task Force