Abstract

This study examined the association between internalizing and externalizing mental health and prosociality across four developmental transitions. The effects of parent–child interactions on mental health and prosociality were also explored. The data from a community sample of 10,703 children on mental health, prosociality, child maltreatment, parent–child relationships, parental mental health, and socioeconomic status were derived from the Millennium Cohort Study to cover the developmental periods from early childhood to late adolescence (ages 5, 7, 11, 14, 17). Adjusting for covariates, latent trait-state-occasion and cross-lag modeling were deployed. The results indicated that internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms, and prosociality were more trait-like throughout adolescence. Only within-person increase in externalizing symptoms predicted decrease in subsequent within-person prosociality from middle childhood to late adolescence. Parent–child conflict and maltreatment had deleterious effects on children’s prosociality and mental health. Mental health professionals should screen for both possible mental health problems and deficits in prosociality. Interventions aiming to improve the quality of parent–child relationships could be beneficial for the development of child mental health and prosociality.

Epidemiological studies have recently documented a spike in internalizing and externalizing mental health problems in child and adolescent populations (Bor et al., 2014; Collishaw, 2015). This evidence is in line with existing knowledge that suggests that many symptoms emerge during these crucial years of lifespan development (Blakemore, 2019). Internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms are broad terms used to encompass emotional/affective (e.g., anxiety, depression) and behavioral (e.g., hyperactivity) symptoms of mental health (A. Goodman et al., 2010). Although child and adolescent mental health symptoms have been connected to both high and low prosociality (Scourfield et al., 2004), very few studies have comprehensively examined the extent to which development in mental health symptoms is related to prosociality in child and adolescent populations. Prosociality, defined as voluntary behavior that aims to benefit another person (Eisenberg et al., 1999, 2015) by caring, showing empathy, and offering psycho-physical assistance. (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020), is a quality that is highly sought after in most societies (Carlo & Padilla-Walker, 2020). However, there is a paucity of studies on life-course interindividual and intraindividual differences in the links between mental health symptoms and prosociality accounting for the impact of the quality of the parent–child relationship.

Developmental theories suggest that the transactional relationships between parents and children are significant predictors of children’s psychopathology (Hudson & Rapee, 2001) and prosociality (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Spinrad & Gal, 2018). Nevertheless, an additional issue, that is frequently disregarded by extant studies, is the role of the quality of parent–child interactions when examining the longitudinal links between mental health symptoms and prosociality. Therefore, in this study, we sought to address these evidence gaps from an early life-course developmental perspective by distinguishing between trait and state mental health symptoms and prosociality.

The Directionality Between Internalizing and Externalizing Mental Health and Prosocial Behavior

Even though there is substantial evidence suggesting that prosociality may predict mental health symptoms, empirical evidence has also emerged indicating that mental health symptoms may also predict prosociality. In general terms, multiple studies have found that prosociality predicts lower mental health symptoms. For example, Haroz et al. (2013) showed that prosociality predicted lower anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents. Similarly, other studies with young children and adolescents indicated that prosociality predicted less depressive symptoms (Perren & Alsaker, 2009) or that deficits in prosociality during childhood predicted a higher risk for the development of emotional mental health symptoms in adolescence (Donohue et al., 2020). In short, one strand of research supports a unidirectional effect from prosociality to mental health symptoms, with higher prosociality predicting lower mental health symptoms.

In contrast, evidence coming from other studies indicates that the directional relationship between symptoms and prosociality is more complex than it seems. Specifically, a recent study found a reciprocal relationship; that is, early prosociality predicted lower externalizing problems and depression predicted lower prosociality (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015). The study by Davis et al. (2016) also indicated a negative reciprocal relationship. Surprisingly, though, some studies found that higher mental health symptoms were predicting higher prosociality (Plenty et al., 2015; Von Dawans et al., 2012), while other studies (McGinley & Evans, 2020; Nantel-Vivier et al., 2014; Schacter & Margolin, 2019) illustrated that adolescents with high levels of prosociality exhibited high mental health symptoms. Given the conflicting findings of preceding empirical evidence, this study sought to address this issue by examining the long-term association of prosociality and mental health symptoms across the formative early years from a latent state-trait perspective.

It is a well-known fact that familial factors have been connected to multiple developmental outcomes and can exert either a protective or harmful influence on children’s mental health symptoms (Bayer et al., 2011; Katsantonis & Symonds, 2023). This idea is conceptually reinforced by the Relational-Developmental Systems theory (Lerner et al., 2015), which suggests that individual children’s development is influenced by and influences parents’ behavioral patterns (Lerner & Castellino, 2002). Thus, we would be remiss to not include relevant familial covariates of internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms and prosociality.

Parent–child interactions have long been linked with child psychopathology (Hudson & Rapee, 2001). In this study, three types of parent–child interactions are considered, namely, child maltreatment, parent–child conflict, and parent–child closeness. Child maltreatment is conceptualized here as verbal and/or physical aggression (Straus et al., 1998). Parent–child closeness and parent–child conflict are two characteristic dimensions of parent–child relationships, according to the conceptual and analytical framework of Driscoll and Pianta (2011). Parent–child conflict refers to quarrels, disagreements, and conflict emotions (e.g., anger; Laursen et al., 1998). In contrast, parent–child closeness is very similar to the concept of attachment, which includes secure relationships with parents characterized by warmth, caring, and communication (Ge et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2019).

Evidence has revealed that early parent–child conflict is a non-negligible predictor of increasing mental health symptoms (Flouri et al., 2018; Parkes et al., 2016). Other studies have also demonstrated the deleterious influence of harsh parental discipline (Bøe et al., 2014; Flouri et al., 2018) on child mental health symptoms development. In addition, studies indicate closeness with parents reduces the likelihood of developing mental health symptoms (Ge et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2019). Fewer studies have connected parent–child closeness with better prosociality (Ferreira et al., 2016), while greater parent–child conflict (Li, 2021) and maltreatment (Yu et al., 2020) have been linked with less prosocial behavior. Yet, the question remains whether these three indicators of parent–child interactions would predict children’s and adolescents’ stable mental health symptoms and prosociality.

Developmental Considerations

From a developmental perspective, children’s and adolescents’ mental health symptoms display, as expected, significant variation across time with most children displaying low levels of mental health symptoms, and some children exhibiting high or moderate levels of mental health symptoms (Flouri et al., 2018; Papachristou & Flouri, 2020). Yet, these kinds of studies cannot quantify to what extent mental health symptoms are trait-like or subject to situational flux. Similarly, developmental studies suggest that prosociality is more malleable to change, requiring some time before it can become more consistent. Prosociality is subject to increase across childhood and early adolescence with adolescents scoring typically higher on prosociality measures (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Malti & Dys, 2018). Although early prosociality skills emerge in the second year of life (Brownell, 2013), prosociality becomes more refined when children are 5 years old (Grueneisen & Warneken, 2022). A meta-analysis has shown that the association between prosociality and internalizing mental health symptoms is stronger in early adolescence but wanes afterwards (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020).

The above raises the question of the extent to which mental health symptoms are stable or fluctuating across the formative years and how stable and occasion-specific prosociality may be connected to mental health symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence. In this study, we distinguish between four major developmental transitions (early to middle childhood, middle childhood to early adolescence, early to middle adolescence, and middle to late adolescence). Different milestones are achieved in each period and children are required to adjust to new expectations (primary vs. secondary vs. post-compulsory schooling, puberty, cognitive and emotional development, etc.; Berk, 2012; Sawyer et al., 2018; Symonds et al., 2016). Thus, the present modeling allows us to disentangle the developmental relationship between mental health symptoms and prosociality across 12 years of life while accounting for the role of the parent–child relationship.

A Latent State-Trait Perspective on Mental Health and Prosociality

Previous evidence did not consider that mental health symptoms and prosociality may be saturated by both a trait-like and an occasion-specific variance. Hence, a Latent State-Trait theory (LST) approach can help disentangle trait from occasion-specific variance.

It is logical to assume that children have a past level (either high or low) of mental health symptoms and prosociality and cannot be assessed in a situational vacuum, as the LST would claim (Steyer et al., 2015). Specifically, according to the basic tenet of LST, human affect, cognitions and behaviors (Geiser, 2020; Steyer & Schmitt, 1990) at a specific time point (called latent states [St ]) are a function of a stable disposition (trait [T]), an occasion-specific residual that captures the effects of situational influences and/or the interaction between person and situational influences (Ot ), and measurement error (εt ; Eid et al., 2017).

In this study, the LST modeling decomposes the variance in children’s mental health symptoms and prosociality into three latent components. The first is a time-invariant latent (trait) factor that reflects children’s stable dispositions toward mental health symptoms and prosociality, while the second is an occasion-specific time-varying (residual) latent factor that reflects children’s temporary developmentally sensitive deviations from the latent trait capturing, thus environmental-situational changes across occasions. Hence, relevant covariates should be included in the LST modeling to adjust the trait- and occasionspecific estimates for environmental-situational influences. Finally, the third latent component is the measurement error of the occasion factors.

Aims and Hypotheses

Informed by the reviewed evidence, the following hypotheses were formulated as guidelines. Given that previous research indicated that the relationship between mental health symptoms and prosociality may be more complex than that covered by simple unidirectional effects, the first hypothesis was that internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms and prosociality would be reciprocally related in the transitory developmental periods between childhood and adolescence (H1). Second, given the importance of warm and accepting parenting behaviors, we expected that early parent–child conflict and physical and psychological maltreatment would be negative predictors of prosociality and positive predictors of mental health symptoms (H2). Finally, it is hypothesized that parent–child closeness would be a positive predictor of prosociality and a negative predictor of mental health symptoms (H3).

Materials and Method

Data Set and Sample

The data come from a community sample of 10,703 children (50% females) from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS; https:// closer.ac.uk/study/millennium-cohort-study/). Most of the children belonged to the White ethnic group (82.15%). Other ethnic groups represented were the following: Pakistani and Bangladeshi (7.35%) and Black or Black British (3.27%), among others. The present sample comprises families and children who were interviewed at ages 5 (early childhood), 7 (middle childhood), 11 (early adolescence), 14 (middle adolescence), and 17 (late adolescence). An unbalanced sample design was adopted to account for longitudinal attrition. Predictors of longitudinal attrition included child sex, ethnic minority status, and lower parental occupation status, among others (Mostafa & Ploubidis, 2017).

Measures

Internalizing and Externalizing Mental Health Problems and Prosocial Behavior. The parent-reported scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; R. Goodman, 1997, 2001; R. Goodman et al., 2000) were utilized across all waves. Although the SDQ scales are not specialized measures of a specific mental health disorder, the SDQ scales exhibit good sensitivity and specificity to detect symptoms of child psychopathology (Cocker et al., 2018). The SDQ has been designed based on the diagnostic criteria of the American Psychiatric Association (A. Goodman et al., 2010) and the scales can accurately predict some of the most common internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms in child and adolescent populations in Britain (accuracy ranging between 89% and 95%; A. Goodman & Goodman, 2011; R. Goodman et al., 2000). Each scale of the SDQ is made up of five items. A sample item for the emotional scale is “Nervous or clingy in new situations.” A sample item for the conduct scale includes, “Often fights with other children.” A sample item for the hyperactivity scale is “Easily distracted, concentration wanders.” A sample item for the peer problems scale includes, “Rather solitary, tends to play alone.” A sample item for the prosociality scale is “Helpful if someone is hurt.” SDQ items were scored using a 3-point scale: 1 = not true, 2 = somewhat true, and 3 = certainly true. Appropriate reverse-scoring was conducted by the MCS team when deriving the scaled scores. The summed composite of each scale’s items ranges from 1 to 10. The composite scores per scale were utilized as indicators. An index of internalizing symptoms is formed as the summed composite of the emotional symptoms and the peer problems, while an index of externalizing mental health symptoms is formed as the composite of conduct problems and hyperactivity (A. Goodman et al., 2010). Prosociality was measured using the prosociality scale of the SDQ.

Child Physical and Psychological Maltreatment. The Straus Tactics Conflict scale (Straus, 2013, 2017) was administered to primary caregivers when the children were aged 5 years old. This scale measures harsh disciplinary practices and indexes physical and psychological maltreatment (Straus, 2013). A sample item is “Smack [the child].” The item response options range from “never” (1) to “daily” (5).

Parent–Child Relationship—Closeness and Conflict. The Parent–Child Relationship short form Pianta scale (Pianta, 1995) was administered to both caregivers when the children were 3years old. An index of closeness was computed as the average of the primary and secondary caregivers’ scores on the closeness subscale, while an index of conflict was computed as the average of the scores on the conflict subscale. A sample item for the closeness scale is “[the child] openly shares his or her feelings and experiences with me,” while a sample item for the conflict scale is “[the child] easily becomes angry with me.”

Covariates. In addition to the main variables, we introduced theoretically relevant covariates into the modeling to minimize the possibility of confounding bias. These covariates were the following.

Child’s Ethnicity. A six-category variable coded using the UK Census classification. It was recoded to reflect the ethnic majority (1 = “White,” 0 = “otherwise”).

Socioeconomic Status. A five-category variable indexing families’ income was coded using the Organisation for Economic Cooperation’s equivalized quintiles ranging from 1 = “lowest” to 5 = “highest.” The variable was derived when the children were aged 5 years old.

Family Mental Health Problems (PMH). The Kessler 6 (K6) scale (Kessler et al., 2003, 2010), which is designed to screen general population samples for serious mental illness, was administered to both the primary (>97% natural mothers) and secondary (>91% natural fathers) caregivers when the children were aged 5years old. An index of each family’s mental health symptoms was extracted in this study as the average of both parents’ K6 scores. A sample item is, “During the last 30days, about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?.”

Statistical Analyses

A modified version (Eid et al., 2017) of the Trait-State-Occasion (TSO) model (Cole et al., 2005) was estimated. This model allows the statistical analyst to disentangle and calculate the proportion of stable time-invariant and occasion-specific variance, and to estimate cross-lagged and first-order autoregressive relationships that control for stable dispositions (LaGrange et al., 2011; Luhmann et al., 2011) for externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and prosociality. In the state-trait modeling, the autoregressive effects are also called “inertia” (Eid et al., 2017) since they describe within-person changes or stability.

The univariate TSO modeling was conducted in the first instance separately for internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and prosociality to calculate the trait- and occasionspecific variances. In contrast to the classical parameterization of the TSO model (Cole et al., 2005), we followed the revised LST that proposed a reparameterization with freely estimated trait loadings instead of constrained to unity (Eid et al., 2017; Steyer et al., 2015). By squaring the standardized regression coefficients for trait (Tt ) and occasion (Ot ), we computed the proportion of state variance in externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and prosociality that was accounted for by the latent trait and latent occasion residuals at each time point since all latent components were uncorrelated (Prenoveau, 2015, 2016).

Although the random-intercept cross-lagged model (RI-CLPM) has become a popular state-trait model for testing reciprocal relationships (Usami, 2021), it assumes that the latent trait loadings are constant over the course of the development (Hamaker et al., 2015). However, this specification is incompatible with the revised LST, which suggests that, although changes in stable traits take longer to manifest, it is still possible that the construct under study can be malleable to change following learning, genetic programming, or life events (Steyer et al., 2015). Since the modified TSO adheres to the revised state-trait theory (Eid et al., 2017; Luhmann et al., 2011), the univariate TSO models were reconfigured into an extended TSO with within-wave correlations and cross-wave lagged regressions (LaGrange et al., 2011; Luhmann et al., 2011). The cross-lag effects are also known as “spillover” or “carry-over” effects (Mulder & Hamaker, 2021) from one occasion-specific factor (Ot ) at time t x – 1 to that of the other variable in the system at time t y . The latent trait factors were correlated to account for stable individual differences. The familial covariates were introduced as predictors of the latent mental health symptoms and prosociality traits.

Since TSO modeling is performed under the structural equation modeling framework, all TSO models were estimated using the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator. Missing data were handled with full-information maximum likelihood (FIML; Enders, 2022). Models’ fit was evaluated using the conventional cut-off indices with values close to/above .95 in comparative fit index (CFI) along with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean residual (SRMR) values below .06 and .08, respectively, being considered as indicators of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To compare nested models, we evaluated each model based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978) since the BIC performs better compared to the conventional fit indices in selecting the “true” population model (Bollen et al., 2014). Lower BIC values indicate better-fitting models (Kline, 2023). Given the large sample, minor effects could reach statistical significance; thus, we set the alpha level at .01 and placed emphasis on the interpretation of standardized effect sizes to gauge the strength of the associations (Khalilzadeh & Tasci, 2017). Finally, we accounted for the MCS sampling weights, stratification, and clustering in the modeling. Pre-processing of the datasets was conducted in Stata 16 (StataCorp., 2019), while TSO modeling was performed with Mplus 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

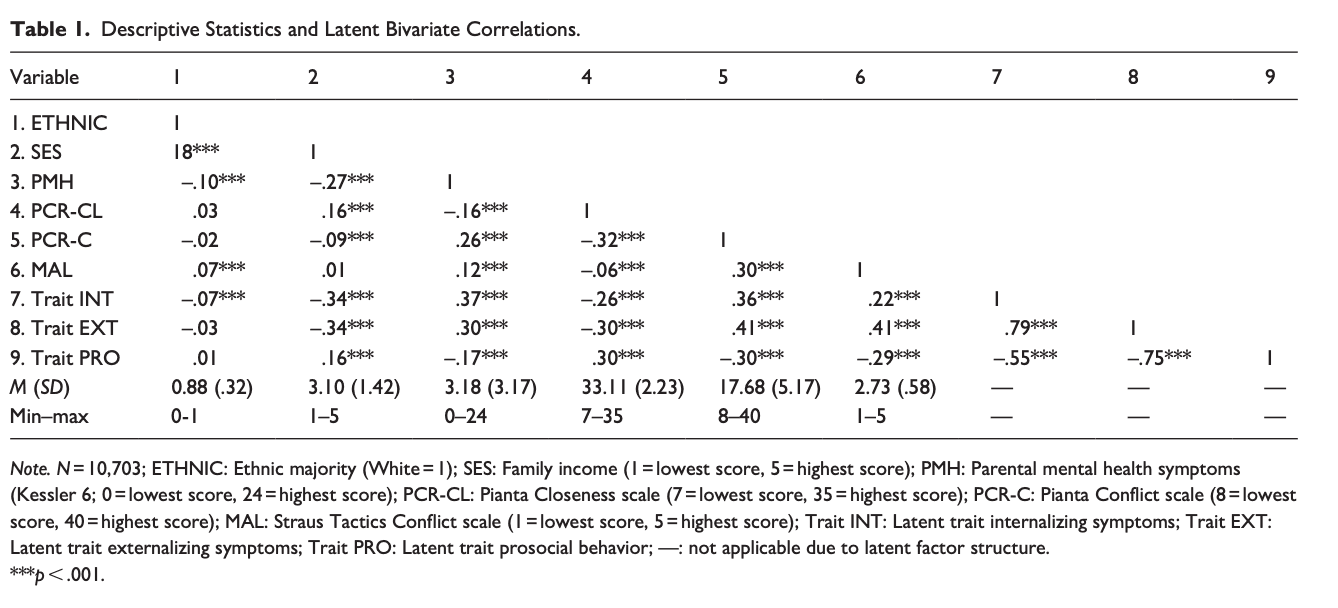

Descriptive statistics, such as means and SDs, and bivariate correlations were calculated for the main outcomes and covariates (Table 1). The psychometric properties of the measures are reported in the supplementary materials.

Variance Partitioning in Trait- and OccasionSpecific Components

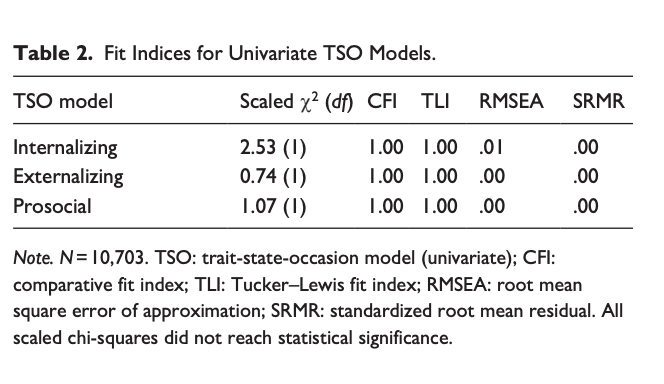

In the first instance, univariate TSOs displayed a good fit to the sample covariance matrices according to the fit indices (see Table 2).

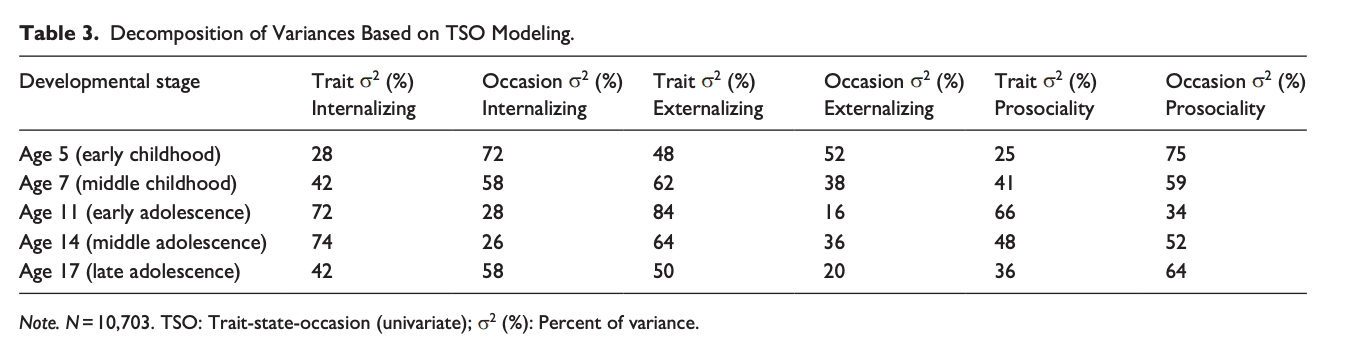

Based on the TSO modeling, it appears that internalizing and externalizing are more trait-like throughout adolescence, whereas prosociality tends to be more oscillating rather than trait-like across childhood till early adolescence (less than 50% of the variances explained by trait factor) and, afterward, it is transformed into a more trait-like psychological construct that is still highly susceptible to situational flux. Both internalizing and externalizing symptoms are more trait-like. The decomposition of variances into states and traits is presented in Table 3.

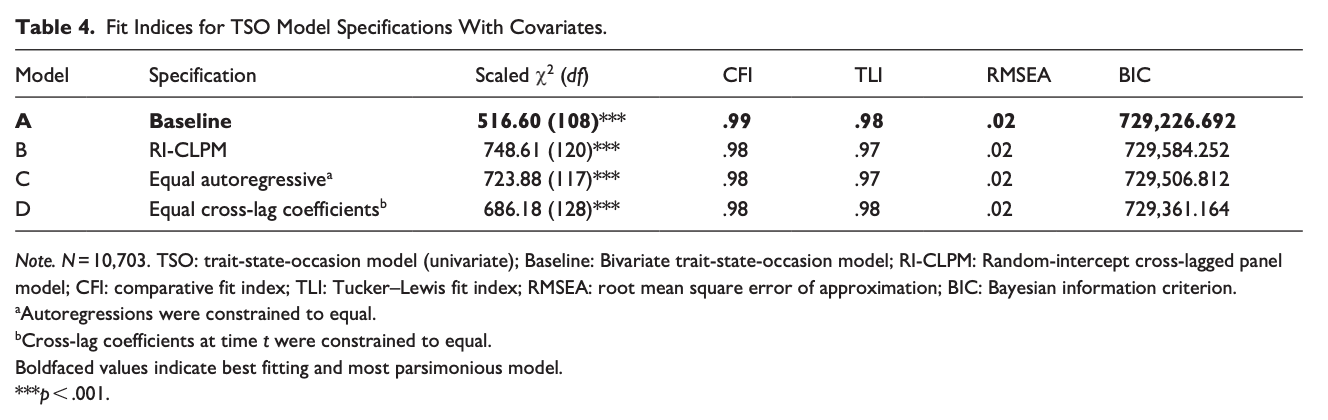

Within-Person Developmental Links Between Mental Health Symptoms and Prosociality

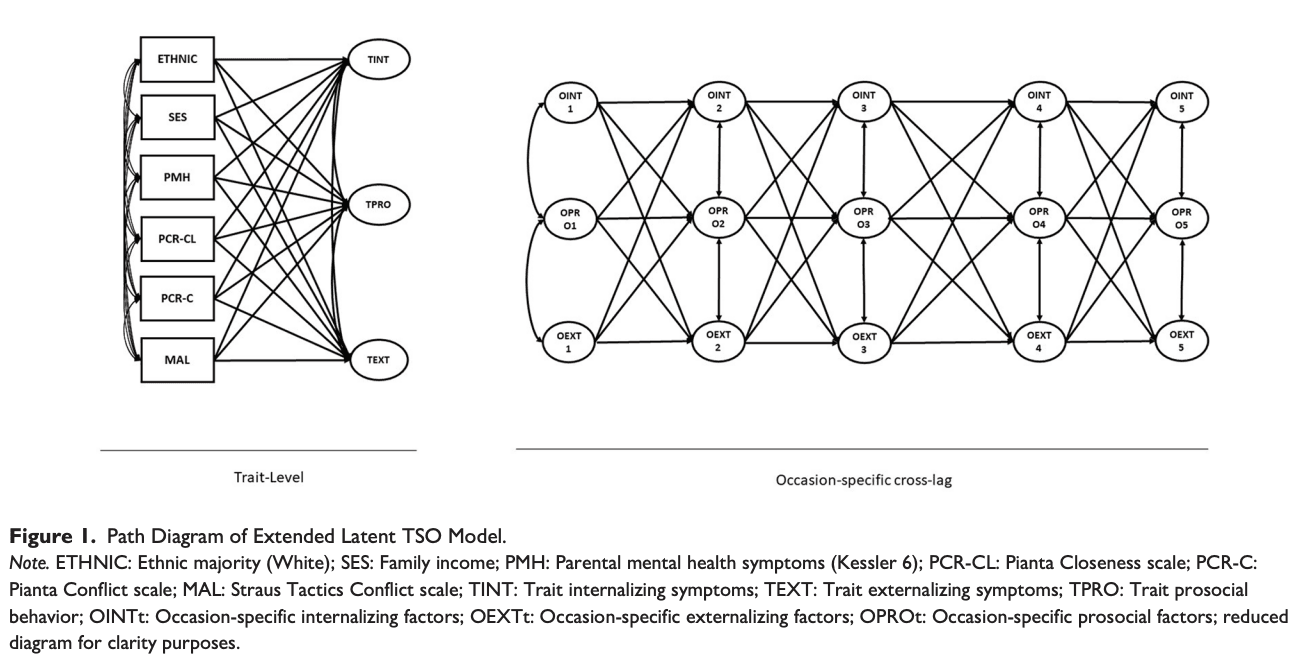

The univariate TSO models were reconfigured into an extended TSO model as shown in Figure 1. Four alternative model specifications were estimated to determine which model formulation was the best. The first model (Model A) was a baseline unconstrained model. The trait factor loadings were constrained to unity resulting in a second model (Model B), which was the random-intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al., 2015). In addition, equality constraints were imposed on the autoregressive parameters in Model C. Finally, the assumption of equal cross-lag coefficients within-wave was tested in Model D. As can be seen in Table 4, Model A is the most parsimonious solution. Thus, the estimates based on Model A are reported.

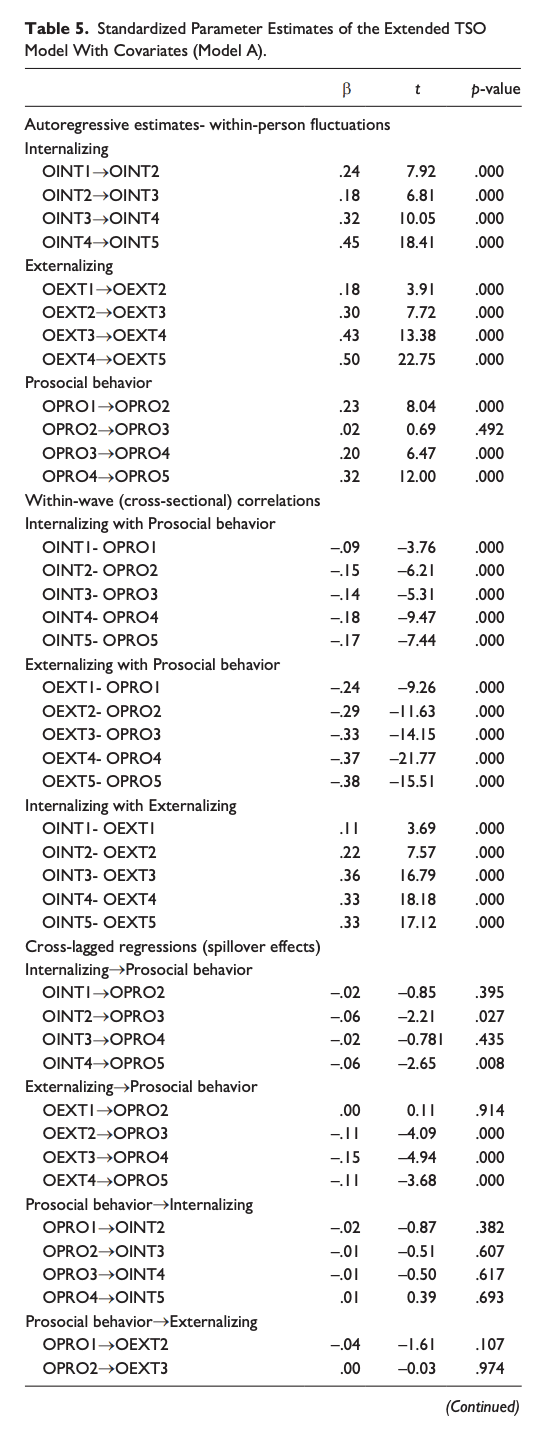

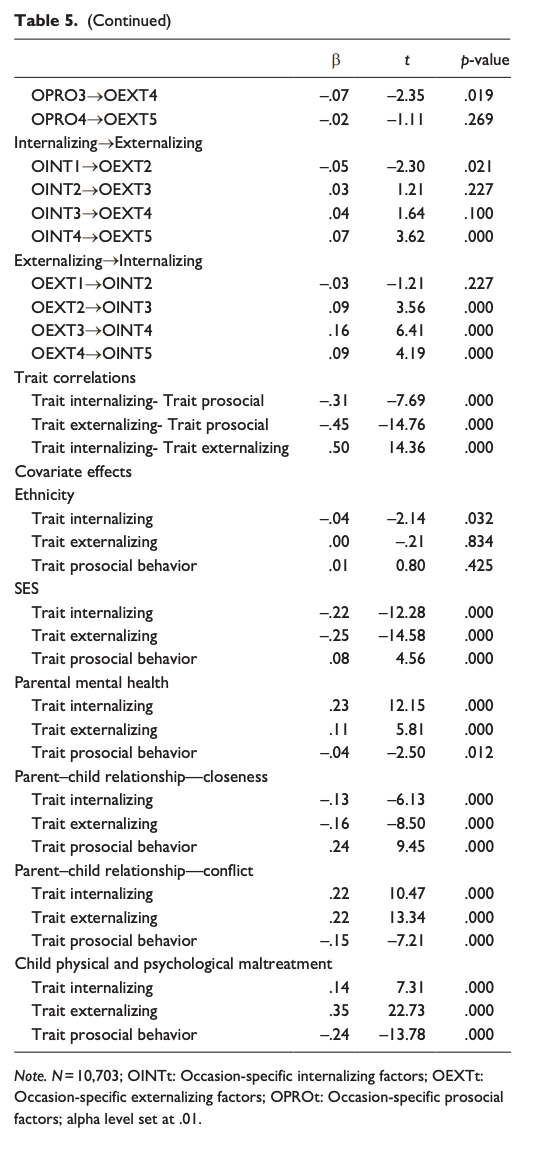

Adjusting for covariates, the extended TSO model indicated that prosociality latent occasion at time t was always cross-sectionally correlated with reduced internalizing and externalizing mental health problems at time t after partialling out the stable trait-like proportion of the variances. The internalizing and externalizing latent traits were negatively correlated with the latent trait of prosociality, which indicated that on average children’s stable mental health problems were decreasing as children’s stable prosociality was becoming more refined from childhood to adolescence. Greater occasion-by-occasion externalizing deviations from the latent trait predicted less prosociality over time, whereas the effects of within-person internalizing changes did not practically predict changes in later prosociality. Earlier within-person prosociality changes did not exert appreciable predictive effects on later internalizing or externalizing mental health symptoms. All in all, the present evidence suggests that only within-person externalizing mental health symptoms are substantial risk factors against prosociality. The directional nature of the relationship between prosociality and mental health symptoms seems to be unidirectional.

Regarding the familial covariates, we found that there was no evidence of the impact of ethnicity on mental health symptoms and prosociality. A social gradient in prosociality and mental health symptoms was found, indicating that greater socioeconomic status (SES) predicted greater prosociality and lower mental health symptoms. Greater parental mental health symptoms were predictive of greater child mental health symptoms but had a non-substantial effect on prosociality. Parent– child relationships characterized by closeness predicted greater prosociality and lower mental health symptoms, while relationships defined by conflict and physical and/or psychological maltreatment predicted greater mental health symptoms and lower prosociality. The parameter estimates are comprehensively shown in Table 5.

Discussion

The developmental links between mental health symptoms and prosociality in the early life course are far from clear. In addition, extant studies exploring the relationship between internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms and prosociality reached inconclusive results regarding the directional nature of this association. Furthermore, the role of parent–child interactions is largely overlooked, even though developmental theory suggests that parenting behaviors influence children’s developmental outcomes (Lerner & Castellino, 2002). Thus, we deployed advanced TSO modeling (Cole et al., 2005; Eid et al., 2017) coupled with nationally representative data to estimate the associations between internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms and prosociality, and to explore the effects of parent– child interactions from early childhood to late adolescence. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined these developmental relationships across the formative years.

The Relation Between Mental Health Symptoms and Prosociality

The findings of the modeling indicated that internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms in children and adolescents were more trait-like in adolescence rather than subject to situational flux. In contrast, prosociality appeared to be influenced more by situational circumstances during childhood, while it became more stable in early adolescence, confirming theoretical tenets suggesting that prosociality becomes more refined later in adolescence (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Malti & Dys, 2018).

Although preceding evidence indicated that prosociality is a negative predictor of mental health symptoms (Donohue et al., 2020; Haroz et al., 2013; Memmott-Elison et al., 2020; Perren & Alsaker, 2009), the within-person transient longitudinal findings suggested that the regression coefficients from earlier prosociality to subsequent internalizing or externalizing mental health symptoms were very weak and did not reach statistical significance at the .01 level, adjusting for the covariates. This finding is unique since a substantial corpus of evidence has come to light indicating an appreciable predictive effect of prosociality on internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms (Donohue et al., 2020; Haroz et al., 2013; Perren & Alsaker, 2009).

Regarding the flow of effects from transient internalizing and externalizing symptoms to prosociality, we found that only transient (within-person occasion-specific) changes in externalizing mental health symptoms were predicting lower prosociality, and this effect held only from middle childhood onward. Although a meta-analysis suggested that the association between prosociality and internalizing symptoms was stronger in early and middle adolescence (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020), our cross-sectional findings did not confirm this since the cross-sectional transient correlations were of negative but of similar magnitude throughout the developmental period. The longitudinal results also did not confirm this since the coefficients from early internalizing to later prosociality were very weak and did not reach statistical significance.

Thus, the above finding is incongruent with previous evidence suggesting a reciprocal relationship between mental health symptoms and prosociality (Davis et al., 2016; Padilla-Walker et al., 2015). Hence, H1 was rejected. In short, this means that children and adolescents with high prosociality scores usually displayed lower mental health symptoms cross-sectionally, but this occasion-specific beneficial effect is not consolidated longitudinally. It ought to be noted, though, that the present approach decomposed the state mental health and prosociality variances into stable and transient components, which means that we looked at changes separately within and between individuals over time which is not compatible with previous approaches.

Moreover, we inspected the latent trait correlations, which described children’s general dispositions (Luhmann et al., 2011) toward mental health symptoms and prosociality. The trait correlation describes the relationship between children’s symptom and prosociality levels across the whole developmental period (ages 5 to 17), which is conceptually similar to a correlation between “averaged” symptom and prosociality scores. Some preceding studies indicated that high prosociality may exhibit cooccurrence with high mental health symptoms (Nantel-Vivier et al., 2014; Plenty et al., 2015; Schacter & Margolin, 2019; Von Dawans et al., 2012), that is, the association might be positive. However, the present modeling results did not support this. The extended state-trait modeling revealed that the correlations between the latent trait prosociality and internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms were negative and reached high statistical significance. The trait-level correlation was slightly stronger for externalizing symptoms, which is in line with past findings (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020). This suggests that individuals who consistently demonstrate high prosociality from age 5 to age 17 generally tend to have low internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms. In other words, children and adolescents who have an innate dispositional mechanism to be highly resilient and have low scores on mental health symptoms usually have high prosociality from early childhood to late adolescence. This reinforces the need to teach young children the value of prosociality in terms of empathy, kindness, being helpful if others are hurt, and volunteering, since this may have a buffering effect against the development of mental health symptoms. Nevertheless, given the absence of strong and statistically significant withinperson regression coefficients from prosociality to internalizing and externalizing symptoms (see Table 5), we need to also place emphasis on other factors (e.g., parent–child interactions, SES), beyond prosociality, to improve children’s and adolescents’ mental health in the community.

The Role of Parent–Child Interactions in the Development of Mental Health Symptoms and Prosociality

Most importantly, we also examined the impact of the parent– child interactions on children’s stable dispositions for internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms, and prosociality. The analyses revealed that high-quality parent–child interactions in the form of increased closeness, reduced conflict, and physical and psychological maltreatment can be very important protective factors against internalizing and externalizing symptoms and can foster increased prosociality.

Our findings corroborate with previous results from survey (Laursen et al., 1998; Lougheed et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2019) and behavior genetics (Burt et al., 2005) studies showing that having a conflicting parent–child relationship (e.g., struggling with each other, sneaking or manipulative child behavior, bad mood) can harm children’s mental health and has been linked with membership to high-risk developmental trajectories. Similarly, being physically and/or psychologically maltreated has been linked with greater mental health difficulties (Coe et al., 2020) and reduced prosociality (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005; Yu et al., 2020). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of studies exploring the links between closeness and mental health symptoms, and prosociality, but the few studies suggest a protective effect (Ge et al., 2009), which is also confirmed here. However, past research has not clarified to what extent these early childhood parent–child interactions were predictive of stable internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and prosociality across the early years (ages 5–17). In other words, greater closeness has sustained long-lasting benefits, while greater conflict and maltreatment have deleterious long-lasting effects.

Covariate Effects on Mental Health Symptoms and Prosociality

Although not of main interest here, the following were found regarding the covariates. Specifically, a social gradient was identified in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, which confirmed preceding evidence (Katsantonis & Symonds, 2023; Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2018). In contrast to past evidence (Piff et al., 2010), we found that higher SES was connected to greater prosociality in the long term. Finally, we noticed a relatively small effect of family mental health symptoms on both stable child symptoms and prosociality. In contrast to earlier evidence in the United Kingdom (Johnston et al., 2013), this suggests weak support for a hypothesis of intergenerational transmission of mental health.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has some significant strengths. For instance, the large representative sample, the long-term longitudinal design spanning the early formative life course, and the advanced analytic techniques are among the advantages of this work. Nevertheless, the present approach also has some limitations. For example, the sample is not diverse enough and does not represent all ethnic groups. In addition, we recognize that the measures utilized are not perfect indicators of mental health symptoms and prosociality, though, it is hard to counterargue that robust representative samples spanning 12 years of the early life span are hard to come by. In addition, the relations between mental health symptoms and prosociality merit further investigation with other established measures and clinical populations to cross-validate the present findings. Finally, an adolescent self-report may have provided more reliable data on adolescents’ internalizing symptoms (Sourander et al., 1999).

Implications

The present findings have significant implications for practice and research. Given that many researchers and organizations invest in mental health interventions that target social-emotional skills and prosociality (Bohlmeijer et al., 2021; Datu et al., 2022; Totzeck et al., 2020; Weare, 2010), the present results would suggest that we need more effective interventions for long-lasting impact.

In addition, within-person prosociality did not appear to have any within-person protective long-term effects on internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms in this community sample. Thus, we need future robust longitudinal studies to extend and deepen the current findings and identify which, if any, aspects of prosocial behavior might be beneficial for different groups of children and which other variables could promote resilient or psychopathological outcomes. Furthermore, the study found that within-person externalizing symptoms (disobedience, fighting, lying, cheating, being overactive and distracted) predicted reduced within-person prosociality over time. As a tentative suggestion, educators and parents could consider clearly outlining social norms and school rules to improve good relationships and minimize environmental distractions.

Based on the current findings, it is also suggested that familybased parenting training interventions may be appropriate, especially in high-risk settings, to reduce the risk of mental health symptoms and prosociality deficits. Finally, knowledge of the current developmental findings is also pertinent for mental health professionals, since the modeling results would indicate that thorough screening for mental health symptoms and prosociality difficulties should be accompanied by a screening of the parent– child interactions.