Abstract

Although a long line of research has examined the association between mental health and offending, previous literature primarily focused on the uni-directional path from mental health problems to offending, or vice versa. Also, there is still much to learn about how different types of victimization are related to the link between the two. To examine these questions, a series of fixed-effect models were employed to examine (1) the assessment of the relationship between mental health and violent offending and (2) the mediating role of experienced and witnessed victimization in that relationship. The results show a significant relationship between mental health and violent offending, while differences were found between the two types of victimization. Limitations and future research suggestions were discussed.

One outcome commonly investigated through a criminological lens is that of violent offending. Through these investigations, several correlations of violent offending have been established. One such correlate that has been shown to influence violent offending is experiencing mental illness (Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Whiting & Fazel, 2020). This correlation was first established in the early 1990s (Monahan, 1992; Monahan et al., 2001; Swanson et al., 1999), and has continued to be examined among researchers today (Whiting & Fazel, 2020).

Despite the longstanding relationship between mental health and violence, several unresolved issues warrant further research. First, previous studies primarily focused on the uni-directionality of this issue. For instance, mental health problems themselves were frequently considered as an individual characteristic that predicts criminal behavior rather than the outcome of criminal behavior. However, there is emerging literature examining both directions of influence (Testa & Semenza, 2020; Wiesner & Kim, 2006). Second, the majority of the research relied on self-reported mental health symptoms. Although the subjective perception is critical in psychological well-being, there may be differences between the mere use of general self-rated psychological symptoms and clinically significant measures, which need further investigation. Third, the role of victimization (e.g., two types: experienced and witnessed victimization) in the mental health-violence association has not been deeply investigated while testing its meditating impacts. There have been consistent findings on the victim-offender overlap, suggesting the important role of victimization when investigating long-term changes in violent offending (Berg & Schreck, 2022; Jennings et al., 2012). Also, people with mental illness are at significant risk to experience victimization (see de Vries et al., 2019; Desmarais et al., 2014 for meta-analyses), and there is also a broad body of literature that demonstrates how victimization can impact mental disorders (Macmillan, 2001; Resnick et al., 1997; Robinson & Keithley, 2000). In particular, along with experienced victimization, there is a relatively limited understanding of whether or how witnessed victimization may affect the link.

Taken together, considering that, “mental health may be seen as either the cause or the consequence of offending, although very few longitudinal studies have looked at reciprocal analytical models” (Reising et al., 2019, p.4), the main purpose of this study is to examine the bidirectional association between mental health and violence over time, utilizing a subsample of serious adolescent offenders who participated in the Pathways to Desistance Study. The Pathways to Desistance Study comprehensively covers various aspects of adolescent offenders, allowing for a thorough examination of the time-varying changes in individuals’ violent offending and mental health problems. We also investigate the role of two different types of victimization (i.e., experienced and witnessed) in the association. Fixed effect models are employed to adjust observed and unobserved time-constant characteristics that may be associated with the key variables of this study while controlling for relevant time-varying factors (Allison, 2009). By doing so, we aim to shed light on the two-way relationship between mental health and violence. Specifically, we emphasize the mediating roles that victimization plays in this connection. This effort is intended to provide valuable insights that can be used to guide intervention and prevention strategies in important areas of public health.

Literature Review

Developmental and Life Course Approach

There are several reasons to suspect that mental health and violent offending are connected. From a developmental and life course perspective, it is reasonable to suspect that they are significantly associated throughout the life course, as the developmental and life course perspective examines the long-term changes of individuals’ behaviors, factors associated with different stages of the life course, and the effects of life events on individual development (Moffitt, 1993; Smith et al., 2015; Thornberry et al., 2014). Given that the developmental and life course approach especially concerns within-individual changes (Farrington, 2003), it would be beneficial to consider the two paths between mental health and violent offending. For instance, juveniles who indicate an increase in mental health problems over time might experience an increase in violent offending, both due to the direct influence of mental health and other factors that occur during that time period. Similarly, on the other side of the spectrum, an escalation in the perpetration of violent offenses among juveniles could worsen their mental health problems, both directly and indirectly, during their adolescent years.

For that potential third factor between mental health and violent offending, prior research highlighted experiencing or witnessing victimization as important factor for the individual’s life course. Specifically, prior studies found that people with mental disorders are significantly more likely to experience victimization when compared to the general population (Khalifeh et al., 2016; Latalova et al., 2014). For example, in a systematic review of 30 studies, Khalifeh et al. (2016) established that people with mental illness had a sixfold higher odds of being victimized when compared to the general population. This is especially concerning when considering the consequences of experiencing victimization, such as hindering social relationships or exacerbating mental health symptomology (Hines & Douglas, 2009), significant predictors of both violent offending and victimization (Silver et al., 2011). In addition to experiencing victimization, scholars have also established a link between witnessing victimization and heightened mental health outcomes (Clark et al., 2008; Howard et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2006, 2013). Witnessing victimization is considered a source of strain and causes negative emotions (Agnew, 2007; Lee & Kim, 2018), which can affect mental health and behavioral outcomes. Therefore, it may be especially important to consider in studies examining mental health and violent offending, as this could also be a linking mechanism. Perhaps for these reasons, research has also established that there is considerable overlap between violent offending and victimization for people with mental illness (Silver et al., 2011), aligning with one of the most established trends in criminological research, the victim-offender overlap. There are diverse explanations for the victim-offender overlap. For instance, routine activity and lifestyle theories propose that the same factors increase both victimization and offending. While general strain theory proposes that victimization can lead to subsequent offending, viewing victimization itself as a significant life event (see Agnew, 2007; Berg & Schreck, 2022; Jennings et al., 2012).

The Path From Mental Health to Violent Offending Through Victimization

Past research indicates that mental health and violent offending are linked. In fact, scholars have consistently shown that people with mental disorders are more likely than the general population to commit acts of violence (Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Monahan et al., 2001; Whiting & Fazel, 2020). Most often, studies hypothesize that the presence of a mental disorder, and related characteristics (e.g., withdrawn, limited interest, poor concentration and selfesteem, and high stress), may impact individuals’ ability to recognize risky situations (see Silver et al., 2011), and potential consequences associated with risky behaviors. More specifically, scholars argue that in times of heightened symptomology, which is sometimes connected to having a mental illness, functional impairment—or the inability to recognize risky situations—may increase the likelihood of being involved in deviant behavior (see Hiday et al., 2001; Silver et al., 2011). Alternatively, it is also possible that those experiencing mental illness may be engaging in maladaptive coping techniques, such as heightened substance usage, that can lead to risky situations (see Meyer, 2001; Ryan et al., 2014). Perhaps a related consequence, prior research has also found that this population are more likely to be rejected by prosocial peers thereby increasing the odds of associating with delinquent friends (Obeidallah & Earls, 1999). This, in turn, may escalate the probability of engaging in future offending behavior.

As research has already found that increased mental health symptomology is significantly associated with both violent offending (Teasdale et al., 2006) and experiencing violent victimization (Maniglio, 2009; Silver et al., 2011), a question that remains is if and how these associations differ over time, and how predictors may differ across the life course. Relatedly, people with mental health issues may also find themselves in situations that are conducive to victimization experiences. Indeed, as stated above, research has already established that this population sometimes has the inability to recognize risky situations and deploy target hardening behaviors to reduce the likelihood of experiencing victimization (Silver et al., 2011). This may be linked to prior findings from research that has already connected heightened rates of victimization for this population to lack of guardianship (Teasdale et al., 2021), engagement in risky behaviors (Hiday et al., 2001), and heightened perceptions of being a suitable target, particularly during times of heightened symptomology (Silver et al., 2011). Of note, these same risky behaviors that influence victimization for this population, also impact violent offending for people with mental illness (see Monahan et al., 2001; Silver et al., 2011). Because of the established connection between mental illness, victimization, and violent offending, research has begun to investigate the link between violent offending and violent victimization for people with mental disorders, an important investigation given the large body of criminological research that highlights the substantial overlap between offenders and victims (Berg et al., 2012; Jennings et al., 2012. For example, using the MacArthur Risk Assessment Study, a longitudinal study of people with mental illness, Silver et al. (2011) found that 13% of their sample had committed violent offenses, 19% had been a victim of violence, and approximately 6% were involved in both—violent offending and victimization. Others have examined how violence impacts the victimization for people with mental illness, consistently finding that violent victimization significantly heightened the odds of engaging in violence (Hiday et al., 2001; Silver, 2002). Finally, some scholars have even concluded that victimization is an important predictor of violence for people with mental health problems (Hiday et al., 2001). In fact, this relationship remains robust even when adjusting for demographic, clinical, and situational factors (Silver et al., 2011). Despite findings highlighting the relationship between violent offending and victimization among people with mental health issues, there is more work to be done to disentangle the mechanisms of how mental health, victimization, and violent offending are connected, since the studies cited above (e.g., Hiday et al., 2001; Silver et al., 2011) focus on an adult population of people with clinical diagnoses of mental illness.

The Path From Violent Offending to Mental Health Through Victimization

On the flip side of this focus, an increasing number of studies also explores the impact of engaging in violent offending on mental health. It is speculated that deviant lifestyles and consequences associated with antisocial behavior (e.g., arrest and confinement) are related to continuous failures in various domains of life (e.g., poor academic achievement and unstable employment) and rejections from interpersonal relationships, increasing risk of poor psychological well-being (Wiesner, 2003). Jolliffe et al. (2019) analyzed a sample of adolescents aged 11 to 16years and found that delinquent behavior was significantly related to later mental health issues. Such findings were consistent with an investigation of persistent offenders regarding their mental health problems. Reising et al. (2019) report that individuals who are showing persistent offending trajectories are more likely to be depressed.

Other research finds linkages between experiencing and witnessing victimization to delinquent (Baglivio et al., 2015) and violent behaviors (Fox et al., 2015). Relatedly, mental health consequences of victimization are especially pronounced among adolescents (Hawker & Boulton, 2000). Indeed, a growing area of research relates to understanding how stressful experiences, such as experiencing victimization, may impact the onset of a mental disorder (Reijntjes et al., 2010; Reijntjes et al., 2011). In the context of this area of research, researchers have demonstrated that experiencing victimization can significantly impact mental health problems (Stadler et al., 2010), with a recent meta-analysis noting that out of 28 studies reviewed, experiencing victimization was a significant contributor to poor mental health outcomes (Goemans et al., 2023). Scholars have also demonstrated that witnessing victimization as an adolescent (such as family violence, for example) significantly contributes to the emergence of heightened stress, which often contributes to the emergence of internalizing or externalizing disorders (Turner et al., 2006). More specifically, previous work has established that witnessing victimization is linked to heightened levels of specific mental disorders such as depression (Turner et al., 2006), substance abuse/dependence (Kilpatrick et al., 2003), or post-traumatic stress disorders (Kilpatrick et al., 2003). As Kilpatrick et al. (2003) note in a National Institute of Justice brief, there is an established link between victimization and mental health consequences.

Method

Data

The current study analyzed data from a subsample of serious adolescent offenders who participated in the Pathways to Desistance Study. The Pathways to Desistance Study is featured in its comprehensive investigation of the long-term changes in adolescent offenders who were mostly found guilty of felony offenses. The data was collected in two sites, Maricopa County in Arizona (n=654) and Philadelphia County in Pennsylvania (n=700), and a total of 1,354 adolescents have participated. The baseline interview indicated that survey participants were ages between 14 and 18 years old, and they were ethnically diverse with 41% African American, 33.5% Hispanic, and 20% Caucasian. The majority of the participants were males (86.4%) and were born in the United States (93.9%). After initial data collection, the following surveys were conducted every 6months for the first 3 years, and then annually interviewed for an additional 4 years. In sum, the Pathways to Desistance Study is comprised of 11 waves of the longitudinal panel data spanning from 2000 to 2010. This study focuses on the first seven waves of the Pathways to Desistance Study, including the baseline and follow-up interviews with 6months terms. The retention rate at wave 7 is 91% and at wave 11 is 84% (Mulvey et al., 2014). Among the total 1,354 participants in the PTD dataset, the number of completed interviews varied as follows: 1,262 at the 6-month follow-up, 1,261 at the 12-month follow-up, 1,230 at the 18-month follow-up, 1,230 at the 24-month follow-up, 1,232 at the 30-month follow-up, and 1,238 at the 36-month follow-up.

Measures

Key Variables. Violent offending variety proportion was assessed by a part of the Self-Report of Offending instrument (Huizinga et al., 1991). A total of 11 offenses were classified as violent offenses, and separate questions were asked regarding each offense committed during the last 6months. The count of different types of violent offenses committed during this period was divided by 11. This calculated number represents the variety proportion of violent offending. Variety scales are frequently used in the field of criminology as a common method of examining offending since it has higher reliability and greater predictive validity relative to frequency measures and a higher correlation with official criminal measures compared to other types of selfreports (see Piquero et al., 2013; Sweeten, 2012). Given the interdependency between variety, frequency, and seriousness, “the greater the variety of deviant acts admitted, the greater their frequency and the greater their seriousness, in general” (Farrington, 1973, p.108). The higher the value, the greater variety of offenses the youth engaged in. The example items included beating up somebody badly needing a doctor, being in a fight, and killing someone (Hampton et al., 2014; Lee & Kim, 2022; Piquero et al., 2013; Walters, 2014). The averaged internal consistency of the measure was .74 across waves.

Mental health was measured by the use of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), which consists of nine subscales (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism) of an individual’s mental health symptoms with 53 items. The results from confirmatory factor analysis report that each subscale of mental health symptoms is a single factor solution. This study used the number of subscales on which the participant reaches clinical significance (Davis et al., 2017; DeLisi et al., 2016; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Piquero et al., 2016), which was created based on the BSI manual. So, the ranges of the variable are 0 (none of the nine subscales reach clinical significance) to 9 (all of the nine subscales reach clinical significance).

Mediating Variables. The current study adopted two types of victimization as mediating variables. Both experienced and witnessed victimization were measured using the Exposure to Violence Inventory (Selner-O’Hagan et al., 1998). Experienced victimization was assessed in a total of six items, and example questions included “In the past 6months, have you been chased where you thought you might be seriously hurt?” and “In the past 6months, have you been beaten up, mugged, or seriously threatened by another person?” The sum of six items was dichotomized to indicate 0 as none-experienced victimization, and 1 as experienced victimization. Witnessed victimization was questioned by seven items and the example question is “In the past 6months, have you seen anyone get chased where you thought they could be seriously hurt?” and “In the past 6months, have you seen anyone else get beaten up, mugged, or seriously threatened by another person?” Witnessed victimization was also dichotomized as none or witnessed. Both experienced and witnessed victimizations were repeatedly measured across all seven waves used in the current study.

Control Variables. We included nine time-variant covariates as the control variables of the estimation. Control variables were selected based on prior research that identified their relevance to violent offending, victimization, and/or mental health (DeLisi et al., 2016; Piquero et al., 2016). Gang membership indicated the status of the participant’s gang membership for the last 6months (no coded 0, yes coded 1). Part of the Parental Monitoring inventory (Steinberg et al., 1992) was adopted to assess the Parental monitoring variable for this study. Four questions on a 4-point Likert scale (“doesn’t know at all” to “knows everything”) asked about their primary caretaker’s behavior such as setting up a time to be home on weekend nights, which represents that higher scores indicate greater parental monitoring. Parental warmth and hostility were measured by questions from the Quality of Parental Relationships Inventory (Conger et al., 1994). Questions about parental warmth and hostility were asked separately about their mother and father. Parental warmth is measured by items such as “How often does your mother let you know she really cares about you?” and “How often does your father tell you he loves you?” Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores representing more parental warmth. Items for parental hostility are such as “How often does your mother get angry at you?” and “How often does your father throw things at you?” There are a total of 42 items, 21 items for maternal and paternal respectively, and responses ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with higher scores indicating greater hostility. Unsupervised routine activities were measured by using the questions from the “Monitoring the Future” questionnaire (Osgood et al., 1996). Items questioned the respondent’s activities in the absence of an authority figure and the number of nights spent on fun activities. The higher score indicates more unsupervised routine activities. Alcohol use was assessed by a questionnaire that asked about a frequency of alcohol drink consumption in the recall period. In addition, participants were asked how many times they used marijuana during the recall period.

Analytic Strategy

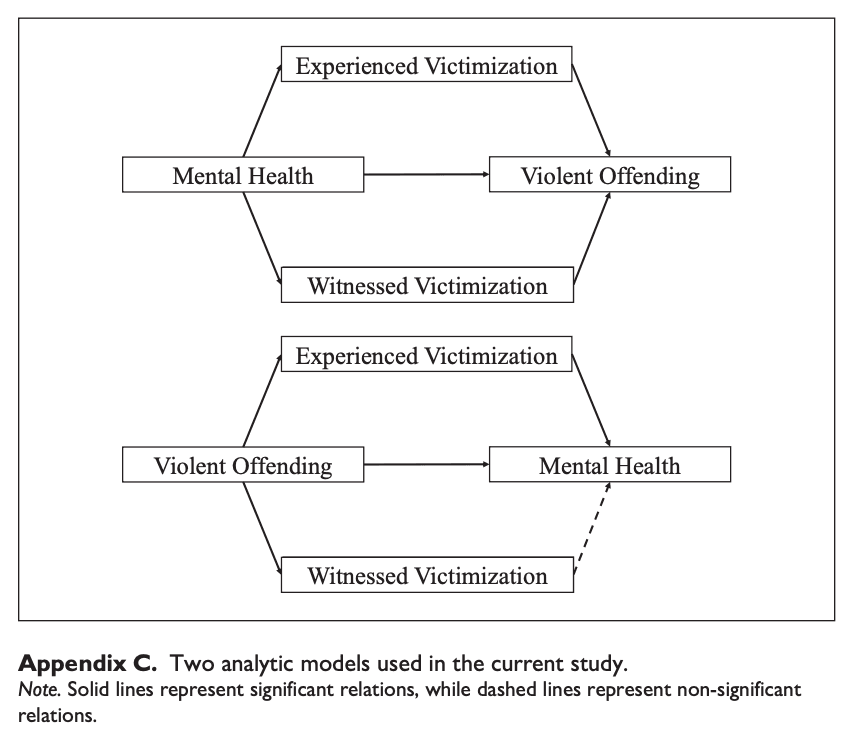

We adopted the following steps to examine the bi-directional relations between violent offending and mental health with the consideration of mediating roles of experienced and witnessed victimization. We employed repeated measures across the first seven waves of the data for estimation. First, we provided descriptive statistics of all dependent and independent variables, which shows the general information of the study participants. Second, we used conditional fixed-effect logistic regression models to assess the effects of mental health and violent offending on mediators. For a better presentation of the findings, we re-organized the results from the separate models into a single table. Panel A shows the effect of mental health on mediators, and panel B shows the effects of violent offending on mediators. Third, we adopted fixed-effect models to examine the impact of mental health on violent offending. More specifically, fixed-effect models were specified into four models that start with a basic model without mediating variables, model 2 included experienced victimization with all factors from model 1, model 3 included witnessed victimization with all factors from model 1, and model 4 included two mediating variables with all control measures. Therefore, fixed effects of key variables (i.e., violent offending and mental health), mediating, and control variables were considered in the models. Fourth, since the current study mainly focused on bi-directional relations between mental health and violent offending, the last step adopted the same analytic steps from the previous examinations with a different analytic direction, which is from violent offending to mental health. The current study mainly adopted fixed-effect models for the main analytic approach, since fixed-effect models have the advantage to examine the changes within a person while controlling for observed and unobserved time-invariant individual characteristics (Allison, 2009). Therefore, such benefits of fixed-effect models allow us to focus on longitudinal changes in violent offending and mental health without potential biases from preexisting individual differences. Missing responses were handled by using the multiple imputation techniques.

Results

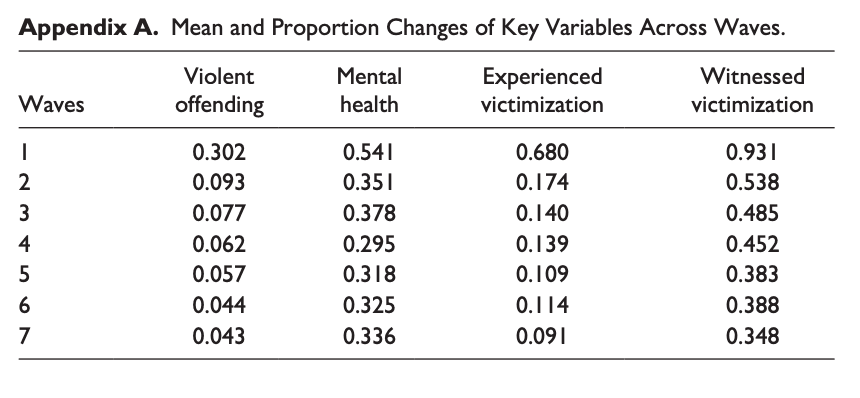

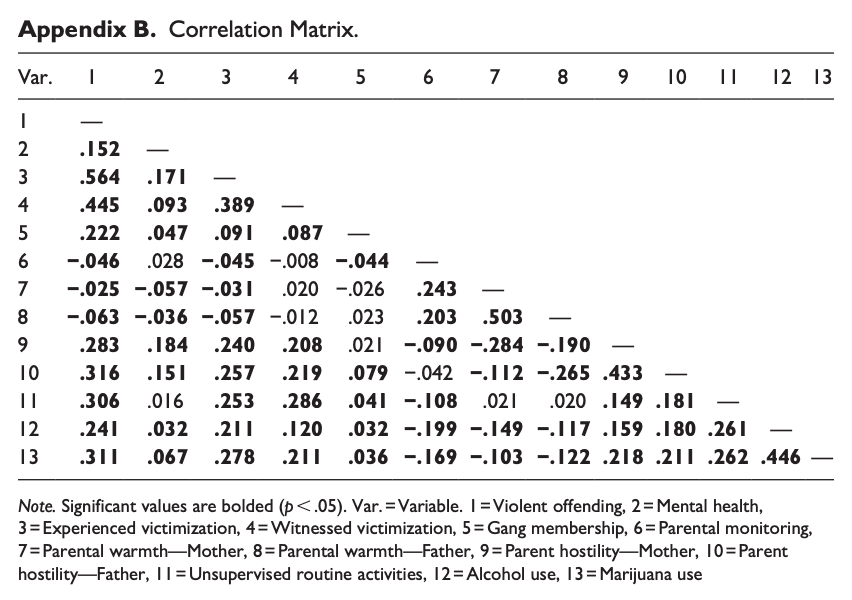

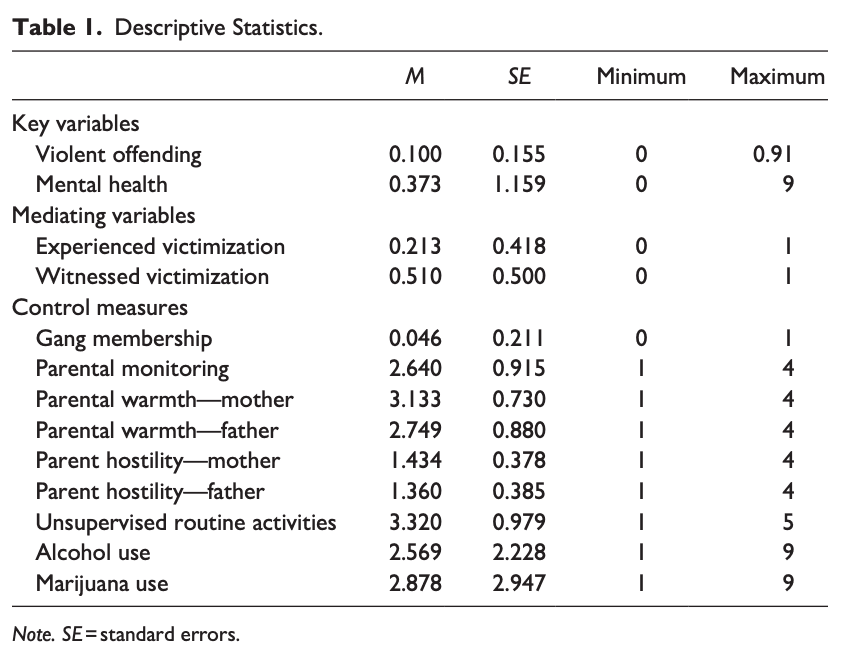

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of all variables examined in the study. The mean score of the variety proportion of violent offending was 0.100 with a standard deviation of 0.155, while mental health was 0.373 as the mean and 1.159 as the standard deviation. Two types of victimization were used as mediating variables, and witnessed victimization (M=0.510, SD=0.500) was more prevalent than experienced victimization (M=0.213, SD=0.418). In addition, the correlation matrix shows all the pairwise correlation coefficients between the study variables, and most indicate the statistical significance (see more details in the Appendix A).

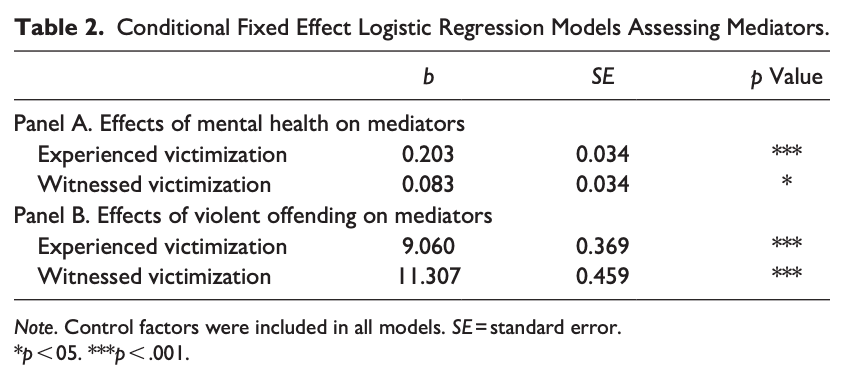

Table 2 reports the effects of mental health and violent offending on mediators. The results indicate that mental health was associated with an increase in experienced and witnessed victimization, and similar findings were identified when examining the effects of violent offending on both types of victimization. Additionally, we conducted the Sobel tests to assess the statistical significance of the mediators (Sobel, 1982). The results from the Sobel Tests indicated that experienced (z=5.872) and witnessed (z=2.418) victimization indicate significant mediation effects when mental health predicts violent offending, while experienced (z=5.550) victimization was only significant when violent offending predicts mental health.

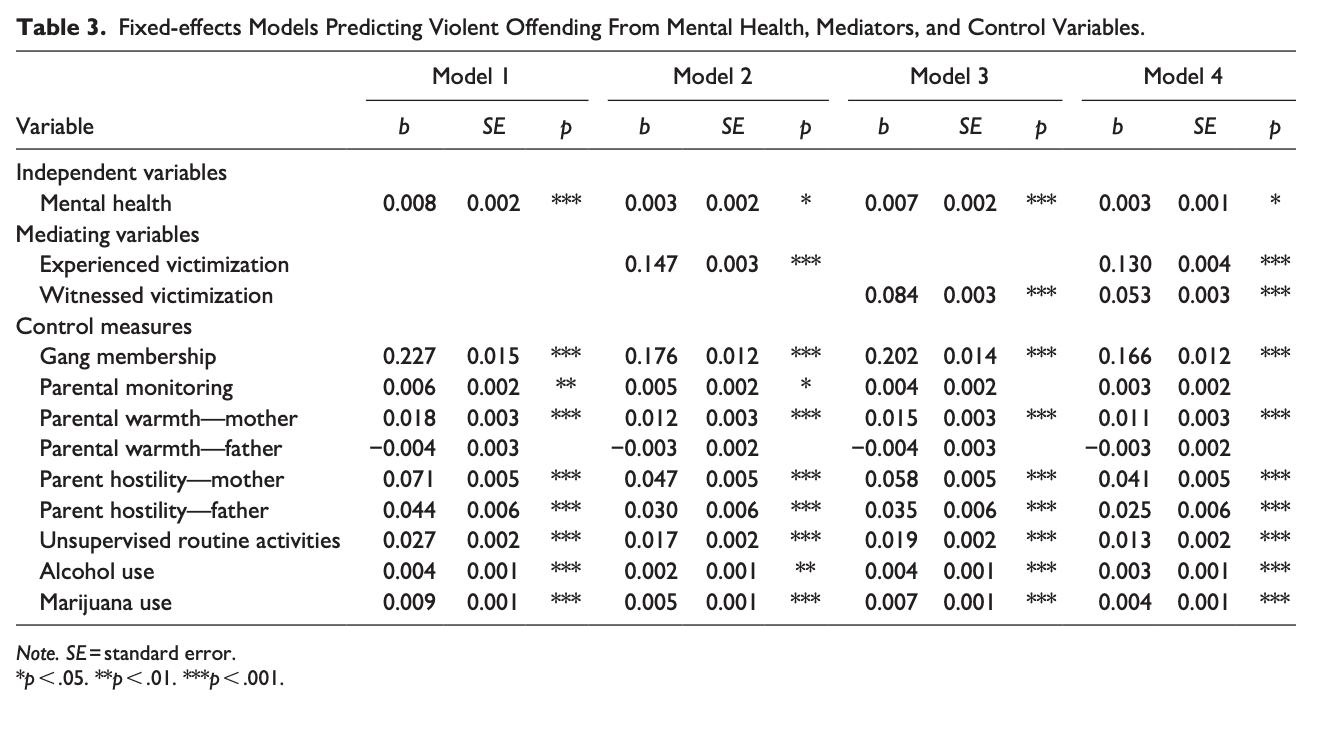

Tables 3 and 4 organized the results from the series of fixed-effect models examining the bi-directional examinations between mental health and violent offending. Initially, Table 3 presents the results from the analytic models that predict violent offending from mental health and mediators. Model 1 shows that mental health was significantly associated with violent offending. The following model included experienced victimization, and both were statistically significant, while the beta coefficient of mental health decreased from .008 to .003. In model 3, witnessed victimization was added to the Model 1, and the results showed that mental health and witnessed victimization were both associated with the increase of violent offending. The beta coefficient of mental health decreased to .007. The model 4 examined the influence of mental health with both experienced and witnessed victimization. The final model also indicated that violent offending was associated with mental health and two types of victimization, suggesting both direct effects of mental health on violent offending and indirect effects through both experienced and witnessed victimization.

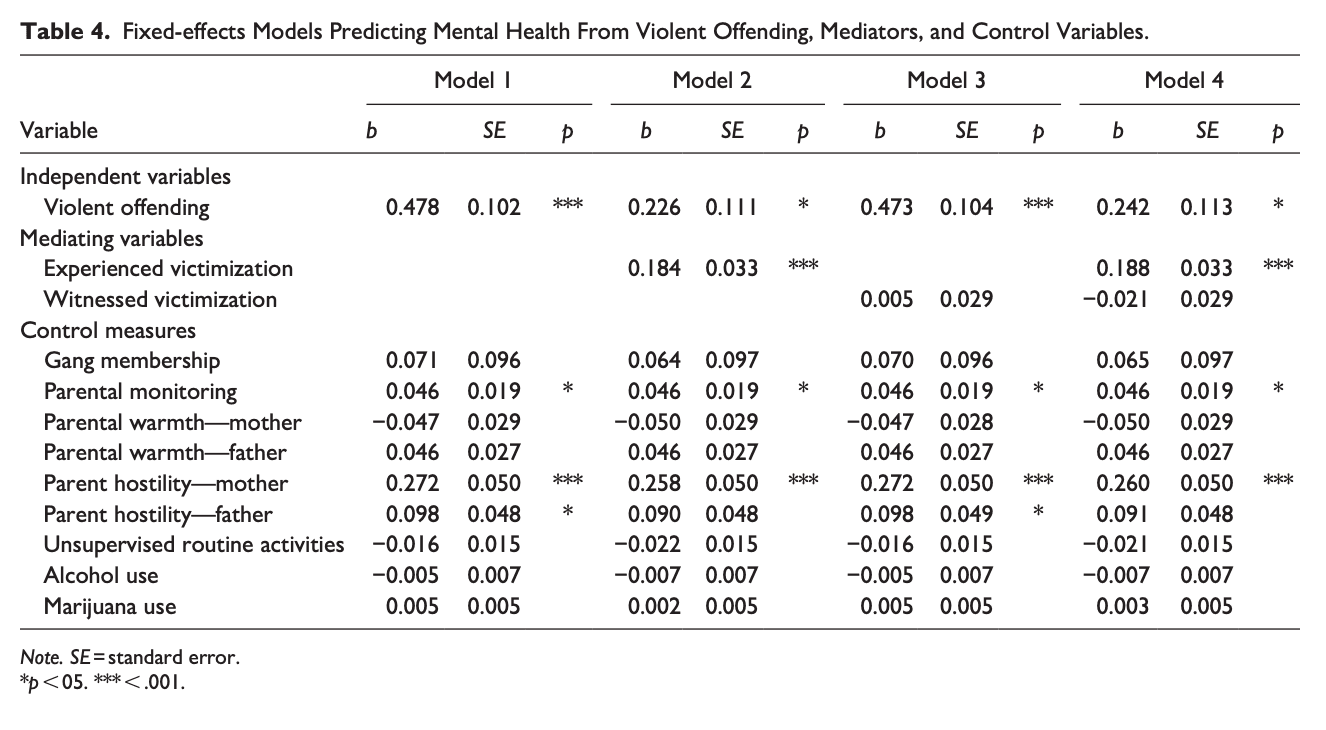

Table 4 presents the effects of violent offending on mental health. In model 1, violent offending significantly increased mental health symptoms. Models 2 and 3 introduce experienced and witness victimization to the models. When experienced victimization was added to model 2, both violent offending and experienced victimization were statistically significant, and the beta coefficient of violent offending decreased from .478 to .226. In model 3, only violent offending was significant, while witnessed victimization was not, suggesting solely the direct effect of violent offending on mental health. The final model incorporated both mediating variables, experienced and witnessed victimization, yielding results similar to model 2 and 3. This indicates the direct influence of violent offending on mental health, with only experienced victimization showing significant indirect effects.

Discussion

There has been substantial attention on the role of mental health in the explanation of violence. The majority of findings support the idea that individuals with mental health problems are more likely to perpetuate violent offending (Choe et al., 2008; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Monahan et al., 2001; Whiting & Fazel, 2020). While such findings suggest an important insight, there is a growing question of whether they just as much support the bidirectional relationship between mental health and violent offending. In addition, when considering the repeated empirical support for the overlap between victimization and offending (see Jennings et al., 2012), assessing the role of victimization on the relationship between mental health and violent offending could suggest further insight into the connections.

Based on such background, the current study aims to assess whether the bi-directional links exist between mental health and violence. Additionally, we examined whether victimization mediates the relationship between mental health and violent offending. The results of the current study support the mutual direct impact of mental health on violent offending among late adolescents. However, the varied manners in which experienced and witnessed victimization affect each directional influence warrant further attention and discussion.

Initially, the overall impact of mental health on violent offending was significant, while not substantial throughout the process. Mental health was directly and indirectly associated with violent offending, but stronger effects were derived from both types of victimizations and other control factors such as gang membership and parental hostility. Similar findings were found from previous studies that the presence of mental health problems is related to diverse characteristics, which is associated with the potential increase of deviant behaviors (Kroll et al., 2002; Lynch et al., 2017; Obeidallah & Earls, 1999). This suggests that narrowing attention to the direct effects of mental health might mislead the comprehensive influences of mental health on violent offending. On the other side of the investigation, violent offending provides dominant explanations for mental health problems. More specifically, violent offending maintains a significant impact on mental health directly and indirectly through experienced victimization. It is plausible to assume that the perpetuation of violent offending might lead to negative collateral consequences in the long-term (Drury et al., 2020; Wiesner, 2003).

Second, it is interesting to note that experienced and witnessed victimization needs to be separately classified, especially when examining mental health as an outcome. The findings of the current study indicate that only the experienced victimization mediates the impact of violent offending on mental health, although prior studies also suggest supportive evidence for the significant role of witnessed victimization (Clark et al., 2008; Howard et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2006, 2013). There are potential explanations for this result. Since the participants in the study were serious adolescent offenders, witnessed victimization might no longer be traumatic or stressful experiences that exacerbate or cause mental health problems. On the contrary, in the case of investigating the impact of mental health on violent offending, the significant roles of both experienced and witnessed victimization is noteworthy. The findings may indicate that for individuals with mental health issues who are vulnerable to stress, both types of victimization may worsen their psychiatric conditions by serving as a source of strain, thereby affecting their behavioral outcomes. Considering the tendency that adolescents who are directly victimized are at greater risk of witnessed victimization (Zimmerman & Posick, 2016), it may not be surprising that exposure to direct or indirect violence is related to maladaptive behavior among youth with clinical signs of mental health problems. The results highlight the necessity of paying extra attention to the different types of victimization and their role in the developmental phases of at-risk adolescents (see Agnew, 2002; Baron, 2009).

Third, the results of the study suggest that understanding needs to be extended to developmental changes of individuals who experienced victimization, perpetuate violent offending, and suffer mental health problems at certain points in time. Whether mental health problems proceed to violent offending or not, with a long view of an individual’s life course, we can expect that adolescents are more likely to offend, exposed to more victimization, and worsen their mental health, when they are involved or exposed to any of those life events since all are associated with each other. Such findings are in line with the central tenet of developmental and life-course criminology that emphasizes the importance of comprehensive and integrative approaches for understanding an individual’s offending and antisocial behavior (Farrington, 2003).

Last but not least, the results of the current study hold significant policy implications. Given the bidirectional relationship between mental health and violent offending, it is suggested that treating mental health problems be a fundamental part of rehabilitative procedures. Whether or not the offender reports mental health issues, addressing these problems is crucial, as offending itself potentially increases subsequent mental health issues. Previous studies indicate that a considerable number of jail inmates and prisoners report mental health problems (Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017), yet most of them do not receive proper mental health treatment, consequently leading to increased subsequent offending (Al-Rousan et al., 2017; Fazel et al., 2016). Moreover, extended attention to the various forms of victimization is recommended. While the current study’s findings partially support witnessed victimization’s mediating effects, it still significantly correlates with violent offending. Another study examining prisoners’ vicarious victimization revealed that it increases negative criminal justice outcomes (Daquin et al., 2016). The nature of witnessed victimization suggests its prevalence across diverse contexts, including local communities (Drakulich, 2015), and individual networks (Vogel & Keith, 2015). Hence, emphasizing attention to witnessed victimization could prove beneficial, even in situations where experienced victimization is rare.

The current study is not without limitations. First, the findings of the current study need extra caution since the study sample is comprised of adolescent offenders who are found guilty, which is important to note when attempting to generalize findings. In addition, this study used the clinical significance of mental health problems, which is a more rigorous measure than most mental health measures, such as self-reported mental health symptoms. This approach has benefits that allow capturing the various mental health symptoms in a single indicator, as well as a more objective measure of mental health problems, but that ultimately are limited to explaining serious mental health problems that are clinically diagnosed as problematic. Also, the mental health measure we employ covers nine subscales, such as somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobia, and paranoia, and psychoticism. The following study that focuses on a specific type of mental health symptoms is necessary since it is questionable to expect the same results from our comprehensive indicator, or symptom-specific findings. Additionally, extending the research to include other types of mental health disorders such as anti-social personality/conduct disorder, bipolar disorder, and narcissism would be beneficial for a better understanding of the relationship between various mental health problems and violent offending. Lastly, future work should extend our findings into gender-specific effects. There are several studies that report the gender differences in mental health symptoms, victimization, and violent offending (Broidy, 2001; Compas et al., 1988; DeHart et al., 2014; Dornfeld & Kruttschnitt, 1992; Jang, 2007; Lynch et al., 2017). We expect that examining gendered effects could enhance our understanding of the questions from this study.