Abstract

This analysis provides the first known in-depth qualitative inquiry into if and how juvenile court judges take the psycho-social immaturity and development of adolescents into consideration when making attributions of adjudicative competency of offenders in juvenile court. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty-seven U.S. juvenile court judges, followed by grounded theory analysis. Competency evaluations from psychologists and the juvenile’s age, history, awareness, and mental capacity influence judicial determinations of competency. Although data show that understandings of adolescent development do play a large role in shaping judges’ understandings of juvenile behavior—particularly related to emotional control, irrational behavior, lack of maturity, and social susceptibility—most judges only connected these characteristics to juvenile offending. Although cognizant that juveniles exhibit attributes that diminish competency-related abilities as part of their adolescent development, the majority of judges still stated that adolescent development is not important to them in assessing juvenile competency, potentially demonstrating a cognitive disconnect on these issues. These results indicate approaches to how judges might think about juvenile competency decisions (“building blocks” vs. “holistic” models) and the need for more direct education and training of judges on the role of adolescent development in competency.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there have been vocal concerns about whether juvenile competency to stand trial in juvenile delinquency proceedings can be effectively measured by the Dusky two-prong test.1 According to this test, a juvenile must first understand the charges and legal proceedings that are mounted against him, and, second, he must also be able to assist his lawyer in his own defense.2 Regardless of jurisdiction, a judge evaluating a juvenile’s competency may examine the juvenile’s maturity.3 This may include an assessment of the juvenile’s ability to understand the long-term consequences of his actions and decisions in court, and his susceptibility to being excessively influenced by others, including his lawyer.4 Each of these competency-related abilities is dependent on the juvenile’s psycho-social maturity and developmental status and, particularly, changes in the juvenile’s cognitive abilities resulting from neurological changes in adolescence and early adulthood.5

An appreciation of the extent to which a juvenile offender possesses competency-related abilities, especially by the juvenile judge ultimately making the competency determination, is necessary to ensure that the juvenile offender’s case can be adjudicated without coercion in a “developmentally appropriate way.”6 Therefore, understanding the ways in which juvenile judges consider research on adolescent development that is likely relevant to juvenile competency determinations is integral to ensuring fair and equitable outcomes for juvenile offenders. Further, this understanding may assist states that are considering developing or modifying juvenile competency statutes, as well as help in the design of more tailored and effective educational programs for judges on these issues.7

This Article, which is exploratory as the first of its kind in in-depth qualitative analysis, considers the attitudes of juvenile judges regarding competency to stand trial in relation to their understandings and perceptions of adolescent development and psycho-social maturity. Presenting a qualitative analysis of twenty-seven interviews with a national sample of juvenile judges, we reveal the factors that judges find influential in determining juvenile competency,8 judges’ understandings of existing research on adolescent development,9 and judges’ views on the influence of age on competency and developmental-maturity-related abilities.10 We find that although data show that research on and understandings of adolescent development do play a large role in shaping judges’ understanding of juvenile behavior,11 the majority of judges only connected these characteristics to offending and did not suggest that adolescent development is important to them in assessing juvenile competency.12 Thus, the data presented indicate that many judges consider juvenile competency as largely unrelated to adolescent development and do not see a connection between the two.13 This research does have limitations, as it only portrays the views of twenty-seven self-selected individuals, sampling was not nationally representative, and it is unknown how the views presented here may actually impact juvenile competency determinations in practice. As such, future studies, particularly those that use research designs with experimental components that may provide methodological triangulation on these issues, are warranted.

Nonetheless, we argue that the fact that many judges in our study do not consider adolescent development as relevant to competency determinations, yet still indicate that juveniles exhibit attributes due to adolescent development that diminish competency-related abilities, shows a cognitive disconnect in judges’ perceptions on how adolescent development may affect competency.14 In response, in order to adjudicate juvenile cases in a “developmentally appropriate way,” these results indicate the need for further research and more direct education and training of judges on the role of adolescent development in not only offending, but also in competency.15 This analysis provides the first in-depth empirical qualitative inquiry on how juvenile judges perceive research on adolescent development and how it might affect the competency evaluation process.

I. JUVENILE LEGAL COMPETENCY

Competency to stand trial is a legal protection put forth to ensure that a defendant receives a fair trial.16 Standards of competency for criminal defendants were formalized in the landmark case Dusky v. United States, which established that competency to stand trial in criminal court involves two elements: (1) defendants must be able to assist their attorneys in mounting their defenses, and (2) defendants must fully understand court proceedings and the charges against them.17 This is contrasted with legal capacity, which is a person’s ability to make particular legal decisions such as entering a guilty plea or entering into a contract, and legal culpability, which is a person’s blameworthiness for a criminal act and to what degree he should be held responsible.18

In criminal court, adult defendants are typically declared incompetent due to severe mental illness or an intellectual disability.19 In the juvenile court setting, competency to stand trial played no role until 1967.20 The legal rights of juveniles were not originally viewed as relevant within the juvenile court system given its rehabilitative purpose.21 The juvenile court system was a product of the Progressive Movement beginning in the late nineteenth century, which pushed for the creation of an independent legal system for youth that was neither criminal nor adversarial in nature.22 The first juvenile court was established in 1899 in Cook County, Illinois, and by 1928, all but two states had a juvenile justice system.23 The initial purpose of the system was to rehabilitate juvenile offenders and protect children from maltreatment.24 Particularly, the creation of an independent system for juvenile offenders was built upon the principle that age and immaturity rendered juveniles less culpable compared to adults and, hence, capable of becoming good members of the community if offered suitable rehabilitation.25 Thus, treatment and protection of the child were considered the best responses to delinquent behavior, as opposed to traditional punishment.26

The latter half of the twentieth century saw a gradual increase in legal protections for juveniles generally and their rights found within the adult court setting. Initially, Dusky only applied to defendants tried in criminal court and did not extend to juvenile defendants in juvenile court.27 However, In re Gault established juvenile rights to a fair trial and due process, including a right to an attorney, the right to be protected against self-incrimination, the right to an appeal, and most importantly in this context, the fundamental right to competency to stand trial in juvenile court.28 The constitutional right of competency to stand trial and the potential extension of the Dusky standard suddenly became relevant to juveniles and a meaningful aspect of the juvenile justice adjudication process.29

As competency to stand trial has become a significant component of juvenile justice, issues have been raised as to how the Dusky standards of competency should be practically applied to juveniles. While competency requires that juveniles be able to understand the nature of their charges and assist in mounting a defense, states have been largely silent regarding whether Dusky standards should apply equally to defendants in juvenile court.30 Although several states have formally implemented statutes regarding competency to stand trial in juvenile court, around twenty states continue to process defendants in juvenile court without a well-defined statutory competency standard.31 Among the states that have adopted juvenile competency statutes, thirteen have adopted the Dusky standard almost verbatim, while eighteen states have adopted a version of the Dusky standard.32

The addition of the Dusky standard to juvenile law has left many questions unanswered, particularly whether developmental immaturity should be integrated into competency standards.33 While both adults and juveniles can be mentally ill or disabled, one unique and pertinent feature of the juvenile population is that their adolescent development, as well as their psycho-social immaturity, has the potential to influence competency.34 A few states, such as Arkansas and Florida, have juvenile competency statute provisions related to developmental immaturity.35 However, despite these statutory provisions, juvenile judges have no real guidelines on how to consider the impact of developmental factors, such as age and maturity, on adolescent development in competency determinations, either apart from or alongside the Dusky standard.36 It is also unclear whether judges in these states actually consider adolescent development.37 Judges in other jurisdictions either are not tasked with weighing adolescent development in juvenile competency evaluations or may take such information into account at their own discretion.38

II. ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO COMPETENCY

Research in the fields of neuroscience and psychology on the development of the human brain has produced new insights on and explanations of adolescent behavior in the last twenty years. For adolescents, certain brain regions mature much later than others; for example, the limbic system, implicated in emotional responses to stimuli, matures quickly during the teen years.39 However, the frontal areas, which are responsible for skills associated with executive function, such as controlling inhibition, judgment, decision-making, and planning, do not finish development until an individual is around twenty-five years old.40

This time difference in structural and functional maturation between the limbic system and frontal areas results in an “immaturity gap” between adults and juveniles.41 Although juveniles show similar reasoning ability and general intelligence levels as adults by the mid-teens, their decision-making abilities are significantly worse: compared to adults, juveniles have heightened responses to emotional stimuli and increased impulsivity.42 Juveniles tend to take more risks than adults, in large part due to the heightened value placed on reward and high susceptibility to peer and authority influence.43 Planning abilities of juveniles tend to improve with age, suggesting that rash, impulsive behavior commonly seen in juveniles is the result of the developmental mismatch between the limbic system and frontal lobe.44

In the last twenty years, there has been at least a partial return to the rehabilitative goal of juvenile court, due in large part to an increase in acceptance of research on adolescent development.45 Criminality in youth is thought to be a reflection of impulsivity, poor decision-making, and inability to think about long-term consequences.46 Juveniles make riskier decisions and think less about consequences, which may lead to offending.47 Inhibition control, short-term memory, and processing speed are also stunted during adolescence, which can lead to anti-social behavior fueled by reward and peer influence.48 Therefore, recent research empirically confirms the principles upon which the juvenile justice system was originally built: that age and inexperience make juveniles different from adults and accordingly less culpable.49 The use of research on adolescent development in major Supreme Court cases such as Roper v. Simmons, Graham v. Florida, and Miller v. Alabama has signaled a legal shift toward acknowledging the differences between juveniles and adults in psycho-social maturity, and these cases have removed the most retributive punishments: the death penalty and life without the possibility of parole for juvenile offenders.50

Yet, the same behaviors and tendencies associated with the “immaturity gap”51 that have signaled a legal change in understanding juvenile culpability and punishment have implications for juvenile competency as well.52 Particularly, maturity of judgment in legal contexts is significantly affected by adolescent development.53 Although there might not be substantial differences between the cognitive abilities of “average” adolescents and adults, those cognitive abilities do not specifically help youth with competency-related behaviors for trial.54 For example, a juvenile’s ability to understand the long-term consequences of his actions and decisions in court; his ability to avoid being unduly influenced by others including his lawyer and the judge; the maturity of his decision-making related to waiving legal rights or taking pleas; and his ability to understand legal jargon, the legal process, the charges against him, and the weight of legal decisions are all potentially impaired by the adolescent immaturity gap.55 Each of these competency-related capacities depends on the juvenile’s current developmental status and cognitive abilities, which in turn are directly influenced by the psychological and brain changes that take place in adolescence and early adulthood.56 These capacities, as well as knowledge of trials and legal concepts, appear to be lacking for a huge number of adolescents across age groups and particularly for children under sixteen.57

A few studies have used “competency screening” measures to assess the abilities of juveniles, but these often fail to consider maturity and psychosocial abilities.58 The use of the MacArthur Competence Assessment ToolCriminal Adjudication (MacCAT-CA) as a proxy for competency has shown mixed results when used in juvenile populations.59 The MacCAT-CA has three subcategories thought to measure cognitive aspects of competency: Understanding (the ability to understand the law); Reasoning (the ability to reason in legal proceedings and with respect to legal decisions); and Appreciation (the ability to appreciate legal consequences).60 Although several studies have shown little difference in juvenile and adult competency scores using the MacCAT-CA, some research has found that juveniles between ten and fifteen years old are often incompetent according to this measure.61 Children between nine and twelve years old who have been administered the MacCAT-CA are often significantly more compromised than older adolescents, although the MacCAT-CA may not be able to effectively measure the long-term consequences of Understanding and Appreciation abilities for older juveniles.62 Indeed, older adolescents have shown they cannot weigh long-term consequences, which is exemplified by their readiness to accept “bad” plea bargains for the sole purpose of ending a case.63

Ultimately, research has indicated that juveniles are generally able to understand the words said in court proceedings, but, across all ages, are often unable to properly interpret their legal effect; adolescents possess everyday “competency,” but the inability to be aware of the consequences of decisions and think long-term are signs that psycho-social development can impair abilities necessary for full adjudicative competency.64 Accordingly, whether a juvenile is ruled competent while exhibiting these shortcomings has immense legal significance and potential repercussions and can lead to adjudication involving coercion.65 The Dusky standard, as extended to juvenile proceedings in In re Gault, holds that individuals must be competent to stand trial in order for the proceedings to be fair.66 Yet the inability to help oneself or one’s defense lawyer, susceptibility to undue influence by one’s lawyer, and inability to understand court proceedings handicap the offender and increase the likelihood of an unfair legal outcome.67 If a juvenile lacks the ability to satisfy either or both of the Dusky competency standards due to developmental immaturity, the juvenile’s decisions over the course of the trial could be detrimental to his future.68 Yet, as discussed above, competency screening measures and judicial determinations of competency have not to date actively and effectively taken psycho-social maturity into account to ensure fair and equitable outcomes for juveniles.69

III. JUVENILE JUDGES AND DETERMINING JUVENILE COMPETENCY

Juvenile judges, using evidence, their own opinions, and competency evaluations from psychologists or clinicians, are the individuals who make the ultimate rulings whether or not juveniles are competent to stand trial.70 When looking at competency evaluations, juvenile judges tend to put significant weight on the opinions of a clinician or psychologist who conducts a competency evaluation.71 Age sometimes increases a judge’s likelihood of declaring incompetence, with younger juveniles being more likely to be ruled incompetent, although results are inconsistent.72 For example, within a sample of Chicago juvenile offenders, roughly 27% of incompetent juveniles were less than twelve years old, compared to only 11% of competent juveniles.73 Similarly, in a study of juvenile offenders in Los Angeles, juveniles younger than fifteen years old were more likely to be ruled incompetent than older juveniles.74 Evidence of a mental health issue, such as a psychiatric diagnosis, has also been known to be influential to juvenile judges’ competency decisions.75

Yet there is far less evidence about the influence of developmental maturity on juvenile judges’ competency decisions. A survey of juvenile judges and defense attorneys from seven states showed roughly 75% of judges did not believe that a youth’s developmental immaturity significantly affected competency.76 Conversely, Cox et al., utilizing experimental vignettes, found that judges considered juvenile psycho-social maturity to be significant to judicial determinations of competency for adolescents between twelve and seventeen years of age.77 Thus, the limited evidence that exists on how judges prioritize adolescent development in competency decisions uses quantitative research designs and is conflicting.

Marked changes have occurred in the last twenty years as the justice system, including the Supreme Court, has used research on adolescent development in rulings to recognize key differences in psycho-social development between juveniles and adults.78 However, judges’ attitudes may affect the ways in which they view and rule upon juvenile competency, which may correspondingly shape caselaw.79 Juvenile judges have been recognized as the main individuals who dictate the philosophy of the juvenile justice system.80 A juvenile judge is responsible for ensuring that the court treats juveniles fairly and has the means to offer effective services and treatment to juveniles.81 Therefore, juvenile judges’ appreciation of the role of adolescent development in making competency determinations is both practically and philosophically important.

Overall, it remains unclear how adolescent development may fit into competency determinations for judges.82 There is no national standard for juvenile competency, nor unanimity about the influence of developmental immaturity on juvenile competency amongst juvenile judges.83 Utilizing semi-structured interviews with twenty-seven juvenile judges from across the U.S. and grounded theory methods, this study examines juvenile judges’ perceptions of the factors that affect juvenile competency to stand trial, particularly their understandings and perceptions of adolescent development and psycho-social maturity.84 Specifically, we were interested in determining if, how, and why judges take psycho-social immaturity into consideration when making attributions about juveniles’ adjudicative competency, whether or not judges’ attitudes toward adolescent development and competency related to one another, if judges had been trained on these issues, and if such attitudes might negatively impact the adjudication of cases in juvenile court.85

IV. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research uses qualitative methodology, which allows for complex descriptions, detailed understandings and contextualization of the experiences being studied, and a grounded theory approach.86 Ultimately, our data consist of semi-structured interviews with twenty-seven juvenile court judges from sixteen different states, collected from January 2018 to March 2018. This study has been approved by the authors’ institutional review boards (IRBs).

A. Participant Selection

Purposeful random sampling was used for this research.87 The purposeful sample for this study is a random selection of judges from across the U.S. who sit on juvenile courts and hear juvenile delinquency proceedings. Only juvenile judges whose mailing addresses were publicly available were accessible for study selection, resulting in targeting only thirty-nine of the fifty states. Further, no previous time on the bench, experience with competency, or previous knowledge of adolescent development, neuroscience, or psychology, was required of judges to participate in the study.

Purposeful sampling, which allows for the methodical selection of participants who can provide valuable information relevant to the study’s focus, is a commonly used theoretical sampling technique that provides cases to deeply study the research questions and allow for the emergence of grounded theory.88 While random sampling is often used to provide representativeness and generalizability to a sample and research questions,89 neither were goals of this research, and this study instead used purposeful random sampling, rather than purposeful sampling, for two main reasons.

First, the intent of this research was not to focus on the views of judges in one particular state because juvenile competency is a national issue that affects all juvenile judges in all jurisdictions.90 Therefore, we believed our research questions were relevant to judges from across the United States, and a deep, emergent understanding of these issues, which is the goal of grounded theory research,91 required participants from several states. Since we chose to sample juvenile judges from the across the United States, purposeful random sampling was used because it would be impossible to contact every juvenile judge in the country. There are thousands of judges that review thousands of cases in juvenile courts across states, meaning that every judge who fit the selection criteria could not be contacted or interviewed.92 Therefore, as described below, we chose to randomly select counties and fifteen judges from those counties in order to provide a methodical sampling technique for each state that would provide a feasible sampling strategy. Second, although judges’ jurisdictions did not appear to affect their views in this research, we also wanted to allow for data collection from many jurisdictions in order to allow for and record those differences in views by jurisdiction if present.93

The initial goal for the research sample was between twenty and thirty judges, the model size for grounded theory to reach theoretical saturation.94 The selection of judges for this research occurred in two stages. First, juvenile judges in the state of Georgia were targeted. These interviews served as a pilot for the interview protocol, and a random selection of fifteen judges were sent an interview request via U.S. mail. Juvenile judges in Georgia were targeted at this stage because Georgia has a Council of Juvenile Court Judges that makes the mailing addresses of all juvenile judges in the state available online in one location.95 Once those judges were contacted and some of them interviewed, the protocol was slightly amended for clarity (but no changes to content), and the second stage of selection was undertaken.

Second, a random selection of juvenile judges in thirty-eight other states were targeted. Eleven states (Delaware, Alaska, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont) and the District of Columbia were omitted from the sampling because there was either no public posting of these states’ juvenile judges or the mailing addresses of posted judges were not publicly available. A random sample of seven counties from each of the remaining thirty-eight states was tabulated; then, a random sample of fifteen juvenile judges from across those seven counties for each state was collected from online court websites. Judges were contacted via U.S. mail to request participation. In total, 570 judges were targeted from these remaining thirty-eight states.

Combined with the fifteen judges targeted from Georgia, this study targeted 585 judges from thirty-nine states by mail. This number of judges (585) was targeted in order to obtain a sample of twenty to thirty judges as a model sample size for this grounded theory study. Previous research interviewing state court judges has shown that the interview request response rate for judges is traditionally around 5%,96 meaning that contacting 585 judges was likely necessary to secure the participation of between twenty to thirty judges. In all, twenty-seven of the 585 judges contacted agreed to participate, resulting in a 5% response rate.

B. Data Collection

Sources of data include semi-structured interviews with judges fitting the selection criteria above. The courthouse mailing addresses of targeted judges (N=585), which are publicly available online, were collected, and judges were contacted via U.S. mail with interview requests. Each interview request included a letter with information on the study and contact information for the first author, including email address and phone number. Interviews were scheduled, conducted via telephone, audio-recorded, and transcribed. Verbal consent from participants was also gathered before beginning the interviews.

C. Interview Protocol

Interviews lasted on average thirty-two minutes and ranged in length from thirteen minutes to one hour and three minutes.97 They included areas of questioning, noted below, that allow for the development of grounded theory.98 There was one interviewer, Dr. Colleen Berryessa, who completed all twenty-seven interviews. She was trained via cognitive pretesting, which involves testing the interview instrument with colleagues by asking them to “think aloud” about each interview question to make sure questions are being interpreted as intended.99 She was also trained in dialogic engagement, which involves discussing different points of view on the interview process and protocol with experts in the current methodology and substantive topics of study in order to better attune the interview protocol and process to the research population and study goals.100

Judges were asked several “opinion and values” questions so that they could describe their thoughts about factors that they may consider in determining or evaluating juvenile competency, including things most important in determining adjudicative competency for juveniles, thoughts on reports and opinions of psychologists in these contexts, and other related questions. “Knowledge” questions were asked to seek an understanding of judges’ knowledge of research regarding how juveniles behaviorally, socially, and emotionally develop during adolescence. “Experience and behavior” questions were asked to explore past experiences with research related to adolescent development and training on such issues.

In addition to open-ended prompts, a series of questions from Bradley et al.101 (some of which are not presented here due to space constraints), were asked to assess judges’ opinions on the influence of age on competency-related abilities, as well as when full brain development occurs; judges were asked to provide an age or age range as a response to each of these questions.102 Finally, “background and demographic” questions were asked to identify and capture judges’ basic demographics that could have influenced their perceptions as they relate to the current research.

Table 1. Selected questions asked to assess judges’ opinions on the age of full brain development and the influence of age on competency-related abilities from Bradley et al.

At what age do you think the human brain fully developed?

At what age is a person old enough . . .

a. to understand court proceedings and utilize an attorney in his/her own defense?

b. to weight long-term consequences of trial such as considering plea bargains?

c. to avoid being unduly influenced by authority figures (such as attorneys)?

D. Data Analysis

A grounded theory approach was used to analyze the data.103 Dedoose software was used to organize, store, and code the data in a multi-step process. First, open coding was used, which is the initial process of iteratively organizing data into preliminary themes observed in the data, after twelve interviews were conducted.104 Next, following full data collection, axial coding was used, described by Strauss and Corbin as the process of “reassembling data that were fractured during open coding.”105 During this stage, themes established during open coding were grouped into categories by examining the data to determine how categories are related.106 Finally, selective coding was used, in which the main theoretical patterns were developed by comparing and interpreting categories of data to illuminate the ways in which categories from axial coding are connected, as related to the study’s research focus.107

Further, interrater reliability of the coding scheme was calculated during the coding process to validate the coding scheme. Interrater reliability involves the coding of the data by multiple individuals during data analysis and helps to establish the rigor of a qualitative study’s coding scheme.108 Three independent co-coders coded and analyzed a random sample of nineteen transcripts to calculate the interrater reliability of the coding scheme. Initial interrater reliability was confirmed (Cohen k=0.72), and inconsistencies were remedied through discussion between co-coders. Slight changes were made to data in this piece for readability, but none altered the essences of the presented quotations.

E. Demographics

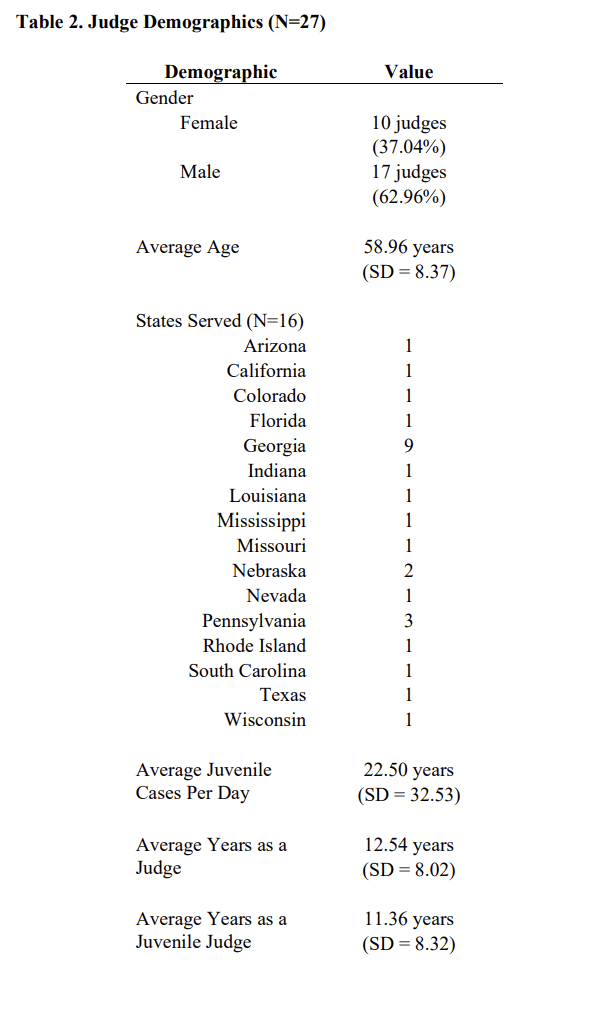

Basic demographics of the twenty-seven interviewed juvenile judges can be found in Table 2. Although social demographic categories (e.g., gender, age, etc.) have been found to potentially influence judges’ views and philosophies,109 none of the demographics collected in this study, including the particular states in which judges served, appeared to be connected to or influence any specific themes observed in the data related to this study’s research focus. Judges were from sixteen different states. All judges handled juvenile offenses in delinquency proceedings and held juris doctor degrees.110

V. RESULTS

Based on the findings, we present five main themes, further divided into sub-themes, that speak to the nuances of the perceptions of juvenile judges on adolescent development in relation to their determinations of competency.111 The first main theme focuses on the perceptions of juvenile judges on the range and importance of factors that they consider in determining juvenile competency (A. Factors that Influence the Determination of Juvenile Competency).112 The second overarching theme focuses on judges’ understandings of existing research on adolescent development and how they believe it generally affects juvenile behavior (B. Perceptions of How Adolescent Development Influences Juvenile Behavior).113 The third main theme examines if, how, and why judges consider adolescent development as important in determining juvenile competency (C. Judges’ Application of Adolescent Development to Juvenile Competency).114 The fourth general theme discusses a series of questions judges were asked concerning at what age juveniles develop competency-related abilities (D. Opinions on Age of Competency-Related Abilities).115 The final theme examines judges’ previous training on and exposure to adolescent development research in legal contexts, as well as their levels of knowledge on and hope for future training on these issues (E. Training on Adolescent Development and Psycho-social Maturity). 116

A. Factors that Influence the Determination of Juvenile Competency

1. Age

Judges reported taking age into account when evaluating a juvenile’s competency, but many did not consider it the most important factor in their determinations. Emphasis was placed on responding to the juvenile in what the judges considered to be an age-appropriate manner, particularly if the juvenile is thirteen years old or younger. Several judges commented that young children might be unable to meet the standards of competency based on cognition and context. Judge 7 linked age to immaturity: “There are some children that may come before the court at very early ages because there are some acute issue[s] going on, but because of their age, they may well be deemed not competent to stand trial just because of their age.”117 Further, most judges believed that the restoration of youth competency (which includes meetings and exercises with a restoration counselor, as well as waiting a period of time in order for a youth to become competent enough to stand trial) for young children was unnecessary and something that judges sought to avoid. As Judge 2 explained, “If you’re 13 years old and you do something, why do I want to put you somewhere for a year or two to get you competent so I can get you back in and then sentence you? That works against solving the problem.”118

2. Awareness

Judges emphasized awareness as important to their considerations of juvenile competency. “Awareness” was described as behaviors that demonstrate to a judge a juvenile’s ability to meet the standards of competency. As such, awareness was considered necessary by judges because “if your goal is to punish someone, then you want to be sure they understand, you know, what it is that is going on and [ . . . ] why they’re being punished.”119 Judge 22 explained what he looked for when assessing awareness:

One is, does the child understand who he is working with? As to an attorney and a judge and so forth. And two, is he able to understand that whatever brought him into court could lead to consequences for him or her? And if he doesn’t know who he’s working with or that there are consequences to things happening in court, I guess beyond those two, we have to take another approach.120

In describing awareness, judges mentioned the importance of certain features and behaviors of a juvenile such as a juvenile’s demeanor in the courtroom and during interviews and conversations with judges. Behavioral cues, judges noted, also bear on juvenile competency, as they are often indicative of how well a juvenile understands court proceedings and can assist his defense lawyer. Several judges also mentioned paying attention to statements made by juveniles about why they had committed criminal acts and the responses that juveniles give when asked awareness-related questions by psychologists during competency evaluations. Finally, a juvenile’s interactions with his attorney were also described to be a key measure of juvenile “awareness.” Judge 12 gave an example of a tell-tale statement:

In the courtroom, you’ll see the child say, ‘Well, I know I did this,’ and the attorney can’t stop them, or ‘I know I’m a bad kid.’ And so, we wind up having statements that show that they don’t understand their rights or that there’s a process and that process could be beneficial to the outcome of their situation.121

3. Evidence and History

The “narratives” of juveniles were highlighted as important for judges in determining competency for the purposes of contextualizing them and their behavior. Judges acknowledged the possible influences of a juvenile’s background and experiences with neglect, abuse, and maltreatment that may affect why a juvenile is in court. For example, one judge stated that she liked to take background into account “because part of the decision-making for me is always, where’s that child going to be for the next period of time? And so, I certainly don’t want to send them to a place that might be detrimental to their well-being.”122

Judges vocalized an interest in obtaining a “fuller picture” of the juvenile in competency determinations, including a juvenile’s background, particularly the psychological and social context in which he is situated. Judges discussed some of the ways in which they are able to obtain this “fuller picture,” such as accessing school records and speaking to parents, case officers, psychologists, and the adolescent’s school to learn about behavior outside of the courtroom. The importance of understanding this background was noted by Judge 4, who explained:

You have a better understanding and perspective on how to handle delinquency cases because a lot of times, you know, children make bad decisions. A lot of times, it’s because of their environment or the way they were brought up or what’s going on in the home and a lot of times that can be changed or affected when they’re very young. But if it’s not caught, then a lot of times these are the same kids that [grow up to] be what we would call a delinquent.123

4. Mental Capacity

The mental capacity of juveniles came up frequently as important pieces of evidence in competency determinations. Capacity, in this context, speaks to the youth’s legal capacity to make particular legal decisions, such as entering a guilty plea or entering into a contract; such capacity can be affected by mental disorder, intellectual disability, or other factors.124

Judges particularly took capacity as it relates to mental health into consideration, often being “particularly concerned about . . . [the] competency of children with special needs.”125 Many judges stated that a juvenile’s mental ability influenced or even often determined whether a judge would decide to move forward with adjudication; particularly intellectual disability, meaning an IQ below 70, was seen as compelling evidence to reject competency. If a child does not have appropriate mental capacity, then he or she will not be able to understand court proceedings, assist his or her attorneys, or communicate effectively, all key elements of competency. Judge 20 gave an example of a previous case in which a defense lawyer did not believe his older juvenile client was competent, but the juvenile was discovered to have high-functioning autism during the competency evaluation. Interestingly, that diagnosis was considered, but ultimately the child was ruled competent, as the judge believed that the diagnosis did not affect the child’s intellectual capacity. Judge 20 stated that such a diagnosis helped both the judge and the lawyer to understand the juvenile’s behavior and tailor the court proceedings to his social and affective deficits.

5. Evaluations

Information collected and reported by psychologists in evaluations was reported by many judges to be most important in competency decisions. In deciding how best to handle the juveniles that come before them, judges frequently use the reports to get a sense of whether competency may be a potential issue. Evaluations were also viewed as a means through which judges could get information while still protecting the child. Judges were aware of the potential for error and the intimidating effect of trying to consider competency without the evaluations.

The evidence found within these evaluations was considered essential for a subset of judges, who acknowledged that they lacked the “expertise and the knowledge to evaluate a child’s or a person’s ability to understand.”126 Yet, for many, evaluations are only one of many pieces of evidence taken into account when determining juvenile competency. A few judges asserted that “no one area is going to be sufficient all unto itself in my opinion.”127 Particularly, trust in the results of an evaluation was important to the weight a judge would give these evaluations. Judges had different expectations for the accuracy and contents of these reports, although many repeatedly mentioned length and amount of detail as greatly important. Some judges typically receive shorter reports, but most who placed high value on evaluations expected longer, more in-depth reports. These judges wanted to see the evaluators describe their methods and provide their sources of information about the child. Clarity in results was also a common desire of judges, along with observations, justifications of results, and for some judges, evaluators’ recommendations for treatment.

Ultimately, the performance of an evaluator is incredibly important to juvenile judges, and some judges appeared suspicious of the methods used by evaluators and the results of evaluations in their jurisdictions. As one judge stated, “Sometimes the evaluation is only as good as those who are arranging it, providing the information, and their understanding of it.”128 Judges who expressed a high amount of trust in reports stated that they only trust these reports at the level they do because they are most often being performed by evaluators with whom they have worked for a significant period of time. Judge 15 expressed that “there are some clinicians I probably have a little bit higher level of confidence in than others, partly because of how much time I’ve spent with them.”129

B. Perceptions of How Adolescent Development Influences Juvenile Behavior

1. Increased Social Susceptibility

Judges stressed that the continuing psychological and neurological development of the juvenile brain makes juveniles more susceptible to the influence of their peers and authority figures compared to adults. Particularly, judges considered peer pressure to be a partial explanation of offending behavior. Judges generally regarded many of the juveniles that come before them not as “criminals,” but young people who have fallen prey to bad influence and would not have otherwise offended if not for their peers. Judge 23 offered an example:

This juvenile, by himself alone would never have done this, but this group of kids in this particular situation, he got caught along, went along with what everyone else was doing, was part of it and then something horrible happened. So, I think it has a big effect on how juvenile offenders and how they— why they do the things that they do. A good example would be . . . kids tearing stuff up, doing things that are just totally illogical. Usually, many times it’s in a group.130

The influence of research on the social susceptibility of juveniles manifested in judges taking a more sympathetic and understanding view of juveniles and their behavior. Rather than taking a punitive approach, Judge 2 suggested that the more judges understand social susceptibility, “the more we know that we shouldn’t hold [juveniles] to the same standard, especially if there’s a group of people.”131

2. Irrational Behavior and Immaturity

Judges also indicated a belief that the rebellious and greater risk-taking behaviors exhibited by juveniles are the result of adolescent development. Judges consistently repeated scientific findings showing that juveniles are more likely to take risks due to lack of impulse control and incomplete frontal lobe development, which is knowledge they have procured from previous trainings. They stated that they often assess how the brain could increase irrationality in adolescent behavior. Judge 6 explained that “there’s no question to me that juveniles and adolescents, because their brains are not fully developed at this point, will make rash or irrational acts and actions that they themselves may not make once they’re 28, 29, 30 and their brains are more fully developed.”132

Judges also explained how an appreciation of this research has led them to adapt their methods of handling juveniles in court. Judge 24 explained that she has worked to simplify the court process for juveniles in her court because of the recognition that juveniles lack the ability to “reason through things and understand consequences long-range.”133 Specifically, she talked about how it influences standards she sets for juveniles that come into her court regarding probation and how she makes terms less stringent than she would for adults. Although she talked about adjusting the court process based on her knowledge of adolescent development, it is worth noting that she did not mention adjusting her lens regarding competency; she ascribed competency related to adolescent development as being relevant to or involved in “the more serious crimes,” while within the juvenile court setting “we don’t see a lot of competency [issues].”134

Finally, judges largely remained cognizant of the fact that criminal behavior of juveniles might be especially emotion-driven. One judge described juveniles as being “more emotionally than pragmatically driven” and later expressed beliefs that juveniles’ “brain development is going to be secondary to their emotional response to things, whether it’s other kids pressuring them, getting upset, reacting, not thinking it through. I just think it’s so intertwined . . . their brain is not as great a resource as it will be later on.”135 Instead of veering toward punishment, their enhanced understanding of juveniles’ developmental immaturity has led these judges to take an approach that is more focused on helping juveniles. As Judge 25 put it, “We expect them to do stupid things. It’s how you limit the potential consequences when you do those stupid things—that’s key.”136

3. Lack of a Developed Value System

Judges frequently referenced the character of juveniles when discussing the influence of adolescent development on behavior. Character was described by judges as an individual’s morals, value systems, and how those morals and value systems influence actions. Juvenile behavior was often discussed in terms of the societal impact; a juvenile’s immaturity is harmful not only to them, but their community as well. Juveniles are less able to meet societal expectations, such as “empathy, the ability to see things from another person’s perspective or to understand the consequences in terms of how their conduct affects other people” because of their adolescent development.137

However, judges regarded juveniles’ lack of developed value systems and poor character not as fixed but merely the result of juveniles’ developmental immaturity. Judge 13 tied together the biological and social elements of this juvenile character development, saying, “I think of it as probably more heavily influenced environmentally than biologically, but it’s all part and parcel of the brain.”138

C. Judges' Application of Adolescent Development to Juvenile Competency

1. Judges Who Do Not Consider Adolescent Development Important to Competency

Surprisingly, despite its influence on their understandings of juvenile behavior, adolescent development had a mixed influence on judges’ determinations of competency. Although judges universally expressed beliefs in findings showing the lack of developmental and behavioral maturity in juveniles, sixteen out of twenty-seven (59.3%) said that adolescent development and the immaturity gap bears no influence on their decisions on competency. These judges viewed adolescent brain and psychosocial development as disconnected from competency. For example, Judge 9 explained that “I don’t know that [information on adolescent development] helps me at all understand juvenile competency. In fact, I truthfully, when it comes to that research, I don’t think any of the research I would’ve seen would explain or help me understand juvenile competency any better.”139

Judge 4 had previously spoken about his experiences of learning about research on adolescent development in prior judicial training and was able to explain the process of brain maturation over time. Research does play a role in his consideration of juvenile behavior generally, as he stated, “We have to consider [research on adolescent development] . . . That’s one reason why they’re juveniles, because you assume that their brain hasn’t totally developed and they make rash decisions without thinking sometimes about different things. So yeah, you have to consider that.”140 Yet, when asked about the potential relationship between juvenile competency and adolescent development, he explained that “competency is different from brain development. . . . That’s a different issue altogether.”141 While he viewed brain development as influential to juvenile decision-making in offending, he did not consider adolescent development as relevant to determinations of juvenile competency; instead, he viewed impaired decision-making as an explanation of why a juvenile was in the courtroom in the first place. This response particularly reflects the sentiments of the other fifteen judges who said that adolescent development bears no influence in their competency decisions. Judge 26 similarly felt that:

Brain development in and of itself doesn’t necessarily affect competency. There might be other things within the section of brain development, if you have intellectual—an intellectual disability, a brain injury, something like that. But I think that’s a little bit different than just, kind of, adolescent brain development. That I think, there’s a whole lot of differences to that kind of adolescent brain development.142

Indeed, although overall judges indicated the importance of a juvenile’s “awareness,” meaning behavioral cues and a juvenile’s demeanor that demonstrate to a judge a juvenile’s competency,143 these judges did not appear to connect how a juvenile’s awareness in competency was relevant to adolescent development. Instead, judges appeared to believe that adolescent development was only connected to criminal actions that result in a juvenile’s presence in court, while competency focuses on awareness as it relates to mental capacity and understandings of the legal process. For example, Judge 20 explained that competency is about “whether or not right now, they’re mentally stable enough to communicate with their attorney to proceed the trial,” while “[adolescent development] research mostly deals—with just consequences and acting in the moment versus thinking about risk and actions have consequences and things like that.”144 Similarly, Judge 19, commenting that competency is a legal but not a psychological concept, stated that during competency evaluations, “you’re asking a psychologist to . . . help you make a determination using terminology that doesn’t mean anything from a psychological perspective.”145

When asked about the possible connection between research and competency, some judges were surprised at the very idea that there could even be a tangible connection between the two. Judge 13 expressed that it was entirely novel to him: “I’ve never thought of that, I’ve generally thought of them as, well—except for very young children, I tend to think of those as independent variables.”146 Judge 10 began to see training differently after being asked about a possible connection between competency and adolescent development. He believed that more training should be given on competency within the context of adolescent development because the relationship was “an area that we all kind of are uncertain about and I never really thought of it as much—you’re making me think more as to how [competency] relates to the adolescent brain.”147

2. Judges Who Consider Adolescent Development Important to Competency

The eleven of the twenty-seven (40.7%) judges who drew a link between competency and adolescent development view brain development as having a “domino effect” on a juvenile’s competency-related abilities, meaning more competency-related abilities are accrued as the brain matures. These judges believe that juveniles, given their limited maturity, have limited understanding that should be taken into account in competency. According to Judge 23:

If their brain function is such that they can’t really control their behavior, at least don’t have the ability to appreciate what it is they’re doing, who it might affect and the consequences, then I think you have to take that into account when you’re determining [competency] . . . So, I think it’s all part of a better, or bigger picture.148

Adolescent development even makes some judges question the competency inquiry itself. Judge 19 emphasized uncertainty “about whether competency is even an appropriate yardstick to apply in juvenile cases.”149

Overall, there are two main dimensions along which adolescent development affects these eleven judges’ views on juvenile competency. First, research on adolescent development has played a notable role in the way that these judges analyze the behavior of juveniles and understand their motivations in the court process.150 Judges go into the courtroom setting with the knowledge and understanding that juveniles have poorer cognitive function skills, judgment and decision-making capabilities, and behave less rationally; as they work, judges try to make sense of the world from the viewpoint of juveniles and the decisions that they are making.151 They then use this understanding as an explanation of behavior, and this explanation then plays a role in how the judge will respond to them in competency-related matters. Judge 7 explained her mental process: “How does a brain affect how one thinks and how one perceives their world and their environment, and how they evaluate what other people do, that’s all part of brain function. You put those kinds of perceptions together and that’s where kids’ behavior comes from.”152

Second, knowledge on adolescent development has led judges to take different approaches when interacting with juveniles in the court setting; in particular, they are more likely to favor using their discretionary powers to tailor the court process to fit the individual child and account for their continuing development. If judges are unable to effectively tailor the process around a juvenile’s deficits related to adolescent development, then competency is questioned. This might involve cautioning attorneys on the social susceptibility of a juvenile or repeating consequences of legal decisions in order for juveniles to understand the full weight of such choices. As Judge 27 explained, “When the kid first comes into court, you know, we need to be figuring out how we are adjusting our language, how we’re adjusting our form, how we’re adjusting our conversation, you know, all of that we need to do in terms of what the research is saying.”153 Overall, understandings of adolescent development have changed the ways that these judges view juvenile behavior and how juveniles might not understand the legal process. Judge 2, a judge who worked as a juvenile judge for the entirety of his career, criticized others for not taking information about adolescent development into account in competency determinations: “I think the more we know about it, the better decisions we’ll be able to make. . . . I think that is inherently wrong for the child, it’s inherently wrong for society when you see how their brains develop.”154

D. Opinions on Age of Competency-Related Abilities

Judges were asked their opinions regarding the age at which individuals gain certain features of competency: the ability to understand court proceedings, the ability to weigh the consequences of trial, and the ability to not be unduly influenced by authority figures, particularly one’s attorney. Additionally, judges were asked at what age they thought the brain fully develops. Every judge who gave a response (twenty-five total) said that the brain developed at the age of twenty-four years old or later. They relied heavily on their previous training and exposure to research as an explanation for their views (“from what I read and heard, the brain development reaches its sort of physical maturity at about age twenty-four”).155 A gap in adolescent and brain development between the sexes was believed to play a role as well, with judges believing that women’s brains mature faster than men’s, explaining the “bone-headed” behavior seen more often in boys.156

Even though all responding judges believed that brain development finishes in an individual’s mid-twenties, most judges’ answers were much lower than that when asked about the age at which a youth acquires different competency-related abilities. Over half of judges felt that a juvenile’s understanding court proceedings was not dependent on age alone and instead was dependent upon the individual child. These judges indicated that they would not strike down competency automatically based on age, even for very young children. Their answers tended to reflect their viewing competency on a case-by-case basis, regardless of age. Ultimately, sixteen judges gave an answer that fell within the range of adolescence (thirteen to sixteen years old), with the rest indicating older ages.

Sixteen judges viewed juveniles sixteen years of age and older as able to weigh the consequences of trial. However, eleven responses were ages between twelve and fourteen years old. Those who believed that only older youth, sixteen years of age or older, could handle these consequences believed that younger children are largely unable to emotionally and cognitively process what a trial entails. The ability to avoid being unduly influenced by authority figures, particularly attorneys, was seen to develop primarily once an individual is past eighteen years of age for about half the sample. For these judges, this ability develops once an individual is able to “think for themselves.” However, over half of judges believed that the ability to resist undue influence from authority figures, like other competencyrelated abilities, should be determined more on a case-by-case basis; these were the judges who primarily answered below the age of eighteen for this prompt. For example, Judge 12 felt that “there are some fifteen-year-olds that are really confident, then there’s thirty-year-olds who can’t stand up for themselves.”157

Regardless of the age at which they believed the brain fully develops, judges’ answers and overall views on these questions indicated two perspectives regarding these competency-related skills. On one side, some judges seemed to view these competency-related abilities as “building blocks” that, with additional information, might “check enough boxes” that a juvenile understands the legal process, the role of his attorney, and other consequences of trial enough to be determined competent. These judges tended to view things on a “case-by-case basis.”158 Judge 8 listed “the learning of mental age” and “social development” as more informative of a child’s ability to handle trials, more so than age. Judge 4 expressed confidence that youth can possess these abilities, saying that “you can have some young kids who know what an attorney is and know how to deal with the attorney and effectively communicate with an attorney. And then you got others that cannot. So, I think at a younger age, sometimes that’s possible.”159 Interestingly, the large majority of judges discussing this “building blocks” model of competency were those that indicated that considering adolescent development is not important to them in competency determinations.

On the other side, other judges, particularly those who tended to give higher ages to these questions, saw competency as requiring several different layers of understanding legal consequences and processes, many of which they argued are not possible in young kids. Judges, moving away from the “building blocks” perspective, argued that all features related to competencyrelated abilities need to be present to indicate juvenile competency. Age played a larger role in their beliefs in competency generally, not on a case-by-case basis. Judge 21 felt that only those older than twenty-one years old could understand court proceedings. From his perspective, “If you say the word ‘fully’ and that’s the problem, because fully, younger people can, you know, in the system, they can utilize it, but they can’t ‘fully’ understand and ‘fully’ utilize it.”160 The large majority of judges discussing this “holistic” model of competency were those that indicated that considering adolescent development is important to them in competency determinations.

E. Training on Adolescent Development and Psycho-social Maturity

Judges reported that they gained their knowledge about adolescent development and developmental science from a variety of sources, the most common being local judicial trainings (seventeen judges or 63%). Trainings were most often part of national or state conferences. Six judges had attended seminars held during the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges conference. The amount of time allotted for these trainings is often sparse; training sessions typically last between forty minutes and two and a half days. In addition to conferences, many judges had attended seminars, usually at the county level for judges, attorneys, and other legal actors, held by mental health professionals on these issues, usually during a lunch in the courthouse (thirteen judges). Judges had also received literature and pamphlets on these issues through conferences and seminars, some of which they refer back to often (thirteen judges). When asked about the content of trainings, seminars, and other information judges had received on adolescent development as part of their judgeships, the overwhelming sentiment was that this information was about adolescent development as it relates to juvenile offending, not juvenile competency.

A few judges also commented on learning about adolescent development from personal experience. Six judges considered their having raised children as beneficial to their understandings of adolescent development. For example, Judge 8 explained, “Some of my own experience both as a dad of two kids and going through that, as well as other children I’ve seen over the years, sort of reinforces what we’ve learned.”161 Judge 25 viewed parenting as helpful in shaping his approach in the courtroom, saying, “I always felt that experience of putting yourself in the shoes of a parent and how you deal with this child, when in doubt, I usually go for that.”162 In these situations, parenting helped judges observe adolescent behavior within an everyday context; their experiences with children in the courtroom are easier because of this, as they are familiar with this behavior and able to easily attribute it to developmental immaturity.

In interviews, judges were asked to rate their knowledge of research on adolescent development. Judges tended to rate their knowledge in terms of four categories: (1) a general rating of one’s knowledge, (2) knowledge as compared to judicial peers, (3) knowledge as compared to the general public, and (4) knowledge as compared to experts on the topic. In response to the general rating of one’s knowledge, nineteen judges rated themselves as higher than six on a general scale from one to ten, showing a tendency to view themselves as very knowledgeable. When comparing themselves to other judges, judges rated themselves highly with an average around 8, suggesting that they may view themselves as more aware of these issues than their colleagues. In comparisons to the general public, the ratings were also high, with the lowest score being a seven and the highest a ten. Comparisons to experts yielded the lowest ratings, with an average of one.

These rankings reflect a pattern throughout the interviews, namely, that the judges expressed confidence in their knowledge. Judge 19 stated that, “I would say I am more open to these concepts [than] most judges. . . . People can know things and they don’t influence how they try to do their work. I’m very influenced by this information.”163 Judge 25 referred to his faith in this research as his having “drank the Kool-Aid early on.”164 Despite expressing confidence in their knowledge, there was overwhelming support for receiving more information about adolescent development. All except one judge held a strong belief that they would still benefit from additional training. They expressed eagerness to be informed of changes in the field and new research findings. As Judge 4 put it, “That’s why you have continuing education. Because, you know, at the minimum you need to be refreshed on it, because you forget, and you need to understand, and you need to know, and research is always changing.”165 Judges were also specific about what they desire to learn. They desire more scientific information about development, as well as guidance on how to treat juveniles effectively within the juvenile justice framework as related to development. They also sought help in figuring out how to respond to and resolve cases in ways that are most beneficial to the juveniles and even how to adjust the juvenile system and their courtroom in response to this research.

While judges indicated that they valued training for themselves, more emphasis was placed on ensuring that their colleagues were properly educated about adolescent development. Judges viewed some of their colleagues critically and in great need of training on these issues. For example, Judge 25 described them as “pay[ing] lip service” to the idea of developmental science,166 while Judge 14 explained how some of the other judges “believe that we should come down on these kids like a ton of bricks.”167 Judge 10 explained the resistance in the judicial “field” to this new information: “It’s science and sometimes judges in the criminal justice systems come kicking and screaming into accepting what really is acceptable science.”168 Increased training was seen as a means through which their colleagues could become oriented towards seeing juveniles as these judges do.

VI. DISCUSSION

Through these in-depth interviews with a sample of twenty-seven judges from across the U.S., we uncover a range of explanations regarding if and how juvenile judges consider adolescent development in determinations of juvenile competency.169 Although data show that research on and understandings of adolescent development do play a large role in shaping judges’ understandings of juvenile behavior, particularly related to emotional control, irrational behavior, lack of maturity, and social susceptibility,170 most judges only connected these characteristics to the underlying reasons for offending behavior and not to juvenile competency.171

This research does have a few limitations. First, although twenty-seven interviewees for a qualitative interview study is large for research on judges,172 this research still only portrays the views of twenty-seven individuals.173 Second, our sample was from sixteen different states, yet was not nationally representative, and for most of the sixteen participating states, only one judge was interviewed from each state.174 Conversely, juvenile judges from the state of Georgia were overrepresented in this study.175 However, as mentioned above, the state in which judges served did not appear to have any connection with their views (e.g. Georgia judges did not appear to express any particular opinions more than other judges).176 That said, our data are not fully nationally representative,177 and we do not know how the views found in this sample may align with those of other juvenile judges across the country.

Third, as discussed in other qualitative research on judges, our interview request may have resulted in a self-selected sample.178 Particularly, these judges may be individuals more likely to be interested in participating in a study on competency than other judges. However, taking these limitations of the sample into account, representativeness is not the goal of qualitative research, and the data from our diverse range of juvenile judges did reach theoretical saturation regarding the themes presented above.179 Finally, we have discussed the views expressed by judges on adolescent development and juvenile competency,180 but we do not have data on how these views may actually impact juvenile competency determinations in practice.

With these limitations in mind, this research produced four main takeaways. First, juvenile judges reported considering the same types of factors when determining juvenile competency as those discussed in the existing literature on judicial views of juvenile competency.181 Although some judges were somewhat suspicious of competency evaluations and many considered them only one piece of the puzzle, opinions put forth in competency evaluations by psychologists or clinicians were described by judges as important to their determinations,182 which is similar to previous literature.183 A juvenile’s age, although described by many judges as considered on a case-by-case basis, was also considered impactful.184 Particularly, similar to Cox et al. and Baerger et al., most judges believed that some very young children likely will not have the awareness to understand legal proceedings or aid their attorneys and therefore may not possess competency-related abilities.185 Finally, evidence of a psychiatric diagnosis or issues with mental capacity has also been known to influence juvenile judges’ competency determinations.186 Our data corroborated the importance of mental capacity in judges’ determinations of juvenile competency.187

Second, our research suggests that juvenile judges are very aware of psychological and neurological research on adolescent development and the corresponding immaturity gap between adults and juveniles.188 They repeated commonly accepted research on these issues and even knew the names of particular brain regions related to adolescent development, such as the prefrontal cortex and limbic region.189

Judges also appear to be very influenced by their understandings of adolescent development when thinking about their own responses to juvenile offending, with the majority believing that it should guide their decisions on how to address juvenile behavior in court.190 These views appeared to be at least in some way influenced by judicial trainings or seminars on adolescent development related to juvenile offending that the large majority of judges in this sample have previously taken.191 Indeed, judges highlighted that they had found the information in these previous learning opportunities helpful, interesting, and imperative in their rulings and in those of their colleagues.192

Overall, judges’ sentiments on adolescent development and its effect on juvenile behavior, particularly offending, mirror the historical philosophy of the juvenile justice system: that age and inexperience make juveniles less culpable for their actions compared to adults and more likely to be rehabilitated.193

Third, although very aware of research on adolescent development and cognizant of the effects it may have on juvenile behaviors related to emotionality, social susceptibility, risks, and judgment,194 juvenile judges were divided on whether adolescent development is important (or unimportant) to determining juvenile competency, with the majority conveying that they saw no real relationship between the two and do not consider it.195 This division supports the limited quantitative research that shows conflicting results on whether judges believe adolescent development and psycho-social maturity is significant to consider in juvenile competency considerations, 196 and this research provides much needed qualitative data that suggests many judges see these concepts as separate, unrelated issues.

Those judges who do consider adolescent development important to competency determinations recognize that juveniles have poorer cognitive function skills, behave less rationally, and should be treated differently than adults during court proceedings.197 Particularly, these psycho-social deficits signal to judges to take different approaches when interacting with juveniles in the court setting, using their discretionary powers with caution and working to tailor the court process to the developmental status of the juvenile in order to make sure they are understanding the legal process.198

On the other hand, it was surprising that sixteen judges saw no connection between adolescent development and juvenile competency,199 as the literature provides evidence that the same behaviors and tendencies associated with the juvenile immaturity gap also have implications for juvenile competency.200 Particularly, juvenile judges recognized how psycho-social deficits associated with adolescent development can affect a juvenile’s judgment and decision-making,201 which are known to significantly influence competency-related abilities, such as a juvenile’s ability to understand future consequences and the weight of his decisions in court.202 Yet most did not recognize these deficits as potentially causing problems for juvenile competency.203 Judges identified key differences between juveniles and adults in their cognitive abilities,204 but these judges generally did not recognize how these differences could affect behaviors related to trial, such as understanding and processing legal proceedings.205 Additionally, although acknowledging that juveniles are significantly more socially susceptible than adults,206 the majority of participants did not discuss or understand how this susceptibility to peer or authority pressure might cause a juvenile to be unduly influenced by others, such as his lawyer and the judge.207 Judges also accepted the immaturity gap between juveniles and adults208 but did not recognize how this immaturity may impair competency-related abilities, such as understanding what it means to waive legal rights, take pleas, or the meaning of legal jargon, legal process, and the charges mounted against them.209

Further, the dissimilar ways in which judges understood age as related to competency and adolescent development were particularly interesting and illuminating.210 Literature indicates that both younger and older adolescents have a demonstrated lack of knowledge regarding trials and legal concepts, as well as the inability to weigh long-term consequences.211 Yet many judges felt that a juvenile’s competency is not necessarily dependent on age or developmental status but should be determined on a case-by-case basis.212 These judges said they would not find a juvenile incompetent automatically based on age or any one factor, even for very young children.213

Indeed, although indicating that brain development does not stop until the mid-twenties, the large majority of judges that indicated that adolescent development is not important to them in competency determinations appear to view individual competency-related abilities, such as the ability to understand court proceedings, weigh the consequences of trial, and not be unduly influenced by authority figures, as “building blocks” that might build a case for the judge that a juvenile is competent to stand trial, regardless of age.214

The ways in which these judges discussed competency allude to the “competency screening” measures that gauge juveniles’ abilities to “understand,” “reason,” and “appreciate” in different categories and ways in order to determine whether a juvenile is competent, regardless of age.215 However, the MacCAT-CA, which uses these three subcategories to measure the cognitive aspects of competency, has been found to be inconsistent in its ability to effectively measure competency across all ages.216 This may suggest that this “building blocks” model may not be an effective method in determining competency, as just “checking boxes” to build a case for competency can leave out other important competency-related abilities and indicators, such as age and developmental status, that are not measured by this method.

Fourth, the fact that many judges do not consider adolescent development as relevant to competency determinations,217 yet still indicate that adolescents exhibit attributes due to adolescent development that diminish competency-related abilities,218 appears to show a cognitive disconnect. We argue that a likely reason that this disconnect exists for over half the judges in this study might be because judges have not yet been taught to think about competency as a psychologically- or developmentally-related concept, and instead, have been only taught to think of offending as a concept related to these issues. To highlight, several judges stated that “competency is different from brain development”219 and “brain development in and of itself doesn’t necessarily affect competency.”220 “You’re asking a psychologist to . . . help you make a determination using terminology that doesn’t mean anything from a psychological perspective,”221 said one judge. For these judges, competency is about “whether or not right now, they’re mentally stable enough to communicate with their attorney to proceed to trial,” while “[adolescent development] research mostly deals . . . with just consequences and acting in the moment versus thinking about risk and actions have consequences . . . .”222

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH