Abstract

## OBJECTIVE To raise awareness and understanding about the role of trauma in the development of substance use and to define and clarify the need for trauma-informed care within the treatment of patients with substance use disorders (SUDs).

## METHOD This article reviews the up-to-date literature on how and why traumatic life experiences promote a neurobiological vulnerability to development of SUDs and combines this with a discussion of the principles of trauma-informed care for SUDs, as well as a review of the role of stigma and structural violence as foundational concepts in the implementation of trauma-informed care for people with SUDs.

## RESULTS Shifting to a trauma-informed care paradigm in treating SUDs more effectively serves patients by improving patient experiences and accounting for a chronic disease model, wherein multiple episodes of SUD care are often necessary.

## CONCLUSIONS This article reviews the ways in which nurses and other service providers can increase SUD patient retention and decrease recurrence by understanding the role of trauma in the development of SUDs, exploring the role of stigma, and identifying and interrupting structural violence as it relates to SUDs. This article also offers actionable steps that all nurses can take now as well as areas for further inquiry into trauma-informed care substance use services.

Introduction

The correlation between adverse childhood experiences and later development of a substance use disorder (SUD) was found to be so consistent over the past 30 years, that in 2019, the American Society of Addiction Medicine updated their definition of addiction, “Addiction is a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences” (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2019). When we change our definition, and our narrative, about what causes SUDs, we have an opportunity to look at how we may best serve those who use substances or have SUDs. Moreover, we have an opportunity to treat and serve people with this disease using the trauma-informed paradigm.

Trauma-informed care has been extensively written about, but the literature about trauma-informed care in treating SUDs has been minimal in recent years. The existing work describing trauma-informed care showed increased patient retention and dropout rate decrease (Amaro et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2013; Hales et al., 2019). This discussion article introduces nurses to an overview of the theory, science, and practice of trauma-informed care in a SUD treatment setting. First, we will describe the neurobiology of trauma as it makes individuals vulnerable to developing SUDs. Then, we will describe the trauma-informed care theory. Next, we will apply the trauma-informed care paradigm in an SUD setting to show its effectiveness in shifting stigma (through language use) and structural violence (through procedural review and revision). Finally, we will offer initial actionable items for nurses and allies to consider to begin implementing trauma-informed care practices in their SUD treatments and offer further areas for inquiry.

The Neurobiology of Trauma and Substance Use Disorder

As mentioned earlier, a shift in the narrative about the cause of SUD is imperative because it helps determine new treatment and engagement pathways. The following review of neurobiology helps inform a cohesive narrative about the cause of substance use. This is in stark contrast to previous understandings of addiction that relied almost entirely on a hedonistic and stigma-inducing narrative: People who struggle with addiction do so because they simply enjoy pleasure too much (Foddy & Savulescu, 2006).

The original Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study was conducted from 1995 to 1997. The authors found that there was a direct correlation between traumatic childhood experiences and risk of substance use later in life (Dube et al., 2003). An ACE score of 4 or more was correlated with a 500% (fivefold) increased risk of developing an alcohol use disorder, and a score of 6 was correlated with a 4,600% (46-fold) increased lifetime risk of injected substance use (Felitti, 2003). The correlation was so strong Felitti (2003) wrote, “Our findings indicate that the major factor underlying addiction is adverse childhood experiences that have not healed with time and that are overwhelmingly concealed from awareness by shame, secrecy, and social taboo” (p. 554).

Subsequent research, seeking to understand this connection, has shown that trauma in early childhood alters the brain in ways that increase the risk of developing a SUD. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is widely connected to areas throughout the brain and is involved in a variety of functions related to executive function, the interpretation of events and construction of personal meaning, suppression of negative emotions, attribution of salience, and regulation of reward circuits (Kessler et al., 2020; Pujara et al., 2016; Zhang & Volkow, 2019). The mPFC typically has strong connections to the amygdala, a brain region which creates feelings of anxiety, fear, and anger when activated. The influence of the mPFC allows individuals to modulate their experience of negative emotions, but in those who have experienced early childhood trauma this connection is weakened. As a result they experience more negative emotions and have less control over them, which has been shown to increase risk of multiple SUDs, and greater reduction in mPFC-amygdala connectivity was found to increase the risk of return to use (Zhang & Volkow, 2019). The mPFC is also connected to the ventral striatum, a region which is involved in monitoring for and response to rewards (Pujara et al., 2016). Increased connection between the mPFC and ventral striatum has been found in both individuals with early childhood trauma and in those with cocaine and heroin use disorders (Hanson et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2010; Wilcox et al., 2011). This increased connection appears to reflect stronger reactions to cues suggesting possible reward and increased motivation to attain substances. Thus, ACEs appear to alter neurodevelopment in ways that increase emotional dysregulation and sensitivity to reinforcing substances and reward (Berridge & Robinson, 2016). Substance use triggers the release of dopamine throughout the brain, which both reduces negative emotions and activates the reward pathways, demonstrating how ACEs can prime young brains to develop SUDs later in life (Zhang & Volkow, 2019).

Moreover, it has been hypothesized that adversity increases baseline hypervigilance and the central threat response system for an unknown, though persistent, duration (Nusslock & Miller, 2015). This hypervigilance, in turn, gives rise to a global inflammation via inflammatory cytokines. Central nervous system inflammation allows reward sensitivity (akin to neural sensitization) in the basal ganglia (Nusslock & Miller, 2015). In other words, people who have experienced adversity may find substances far more salient than their healthy counterparts, especially when their brain is hypervigilant and with a special affinity toward that which seems to signal survival (Huys et al., 2014; Nusslock & Miller, 2015; Yoo et al., 2017).

In short, traumatic experiences, most especially during brain development, actually prime our brains to be hypersensitive to salience and reward, and confuse reinforcing substances for substances that ensure our survival. Understanding this pattern as neurobiological vulnerability instead of moralistic failing again reinforces the need to attend to people with SUD from a trauma-informed approach.

What Is Trauma Informed Care?

According to the seminal work of Hopper et al. (2010), trauma-informed care can be defined as

a strengths-based framework that is grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and that creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. (p. 82)

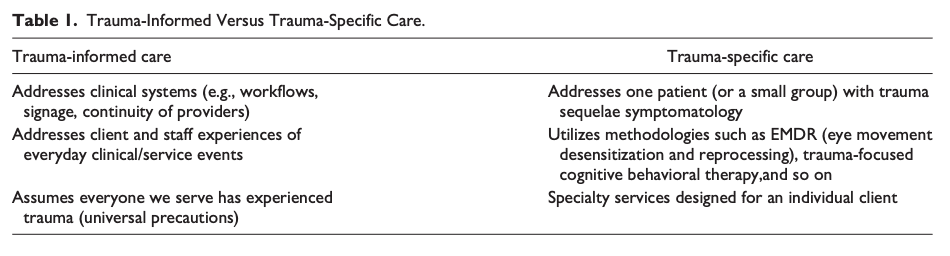

Unlike trauma-specific care, which attends to the symptoms of psychiatric sequelae of traumatic experiences for individuals (Trauma Informed Oregon, 2017), trauma-informed care asks that we change systems to ensure an experience of safety and empowerment for clients (see Table 1). Most specifically, trauma-informed care is vigilant about prevention of retraumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014) by naming the specific ways in which we can either harm or support clients based on their histories. Nurses can and do play a particularly poignant role in trauma-informed care because nurses have always been interested in the patient experience (Peplau, 1997).

Table 1. Trauma-Informed Versus Trauma-Specific Care.

Trauma-informed care is particularly meaningful within the context of SUD for a variety of reasons. Nurses and other service providers must understand trauma is common among people seeking services, and be especially attentive to providing a positive patient experience that does not evoke past trauma (Felitti, 2003; Hales et al., 2019; Merrick et al., 2018). This is important in the context of SUD services because clients may seek our services repeatedly as they build recovery capital (Decker et al., 2017; Hennessy, 2017; Laudet & White, 2008). The less likely they are to feel stigmatized and dehumanized, the more likely they are to return promptly on a recurrence of disease symptoms (Biancarelli et al., 2019).

Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

The key principles of trauma-informed care are safety, collaboration, empowerment, trustworthiness, and choice (Harris & Fallot, 2001). Each principle offers insight in systems design and highlights areas wherein we can attend to the patient experience. If we focus on safety and the client experience, we may be attentive to the way in which we arrange furniture in therapeutic offices and allow easy access to doorways for clients, prioritizing the safety of both clients and staff. If we consider psychological safety, we may arrange bathrooms differently for a urine sample collection, with the understanding that iatrogenic harm can come from the urine drug screen process for trauma survivors. An example of empowerment might look like participants self-authoring group agreements for process or psychoeducation groups. If we focus on collaboration we will write treatment paperwork, such as behavioral agreements, with patient input and voice. Moreover, we may begin to use the collaborative problem solving model for disruptive behavior (Greene, 2011; Greene et al., 2003). Choice in SUD may, for example, highlight the need for clients themselves to determine their treatment goals, versus a unilateral assumption that the end goal is cessation of all substances.

Foundations of Trauma-Informed Care for Substance Use Disorder: Battling Stigma

The foundation for a trauma-informed SUD workforce and clinical system is only possible when the stigma of addiction is actively acknowledged and resisted. According to Avery and Avery (2019), the stigma of addiction is the “negative attitudes towards those suffering substance use disorders that . . . are likely to impact physical, psychological, social or professional well being” (p. 2). Moreover, stigmatization was found by Fleury et al. (2014) to be “the strongest predictor of substance dependence” (p. 203). Researchers have identified multiple layers of stigma, each building on the other to vastly influence the lived experiences of people with SUDs and their families (Hatzenbuehler, 2017). First, there is the vast, far-reaching, and powerful structural level stigma such as policies, laws, and inequitable resource allocation for research (Hatzenbuehler, 2017). More intimately, there is interpersonal stigma; this type of stigma is damaging and includes the ill-treatment of a person who uses drugs by a police officer, health care professional, or clergy—the very people who are supposed to tend to and protect the vulnerable. And finally, personal stigma, the uniquely personal experience of low-self esteem and poor self-efficacy that can hinder attempts at recovery and self-transformation (Hatzenbuehler, 2017). Each layer of stigma compounds the others, ultimately prohibiting recovery and decreasing the health and well-being of the drug user (Hatzenbuehler, 2017), propelling them further away from the thing society most wants from them: recovery. A trauma-informed SUD system ensures that each layer of stigma is addressed but most specifically the interaction between staff and client.

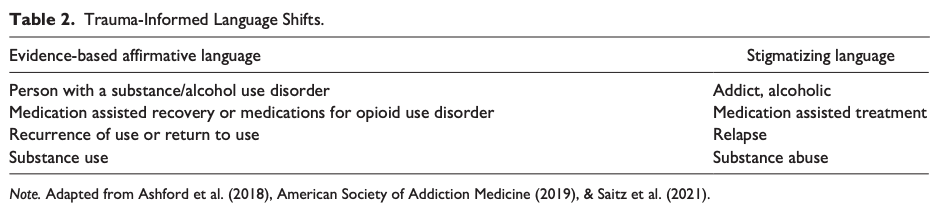

Language choice is one of the most important and actionable steps we as nurses can take today to decrease stigma against people who use substances. The data tell us that some specific words actually decrease stigma for people who use drugs, while other words that we might think of as innocuous are harmful to people who use or have used substances, because they bolster bias and stigma (Ashford et al., 2018; Wakeman, 2017). As researchers have identified, there may be appropriate locations to utilize words like addict and alcoholic (e.g., mutual aid meetings) but this language has no place in clinical practice (see Table 2). It is imprecise, and it allows us to think about addiction from a place of moralism rather than a place of clinical acumen. The word choices described in the attached table affirm human dignity and help reground us in our clinical knowledge, allowing us to move away from the interpersonal stigma that we know health care providers enact (Biancarelli et al., 2019).

Table 2. Trauma-Informed Language Shifts.

Foundations of Trauma-Informed Care for Substance Use Disorder: Structural Violence

Structural violence is defined as:

One way of describing social arrangements that put individuals and populations in harm’s way . . . The arrangements are structural because they are embedded in the political and economic organization of our social world; they are violent because they cause injury to people . . . neither culture nor pure individual will is at fault; rather, historically given (and often economically driven) processes and forces conspire to constrain individual agency (Farmer et al., 2006, p. 1686).

While an understanding of structural violence is imperative throughout health care, it is particularly important in the context of trauma-informed care for SUD for two distinct but intertwined reasons. First, trauma often originates within structural violence. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Violence Prevention explores in a 2019 briefing, one of the primary modes of preventing adverse childhood experiences is to address structural violence, such as poverty and wealth inequity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Thus, in order to understand trauma and toxic stress and its long lasting effects on our neurobiology, we must understand that traumatic experiences are not generally individual experiences but instead are shared experiences with a foundation in systemic problems such as racism, socioeconomic inequity, and gender based violence. One example highlighting the role of structural violence is reflected in the original ACES questions and asks about losing a family member to incarceration. African Americans and Blacks are disproportionately criminalized and incarcerated compared with their White counterparts based on systemic racism and historical criminalization (Bailey et al., 2021; Biancarelli et al., 2019; Jeffers, 2019).

Second, when we fully understand the way in which structural violence gives rise to traumatic experiences, we can then understand how best to transform our services to ensure that retraumatization based on structural violence is less likely to occur. For example, trauma-informed SUD services may be especially attentive to the implicit bias that White clinicians can, and do, exhibit with their Black, Indigenous, or people of color clients, most especially in the context of substance use, which is heavily stigmatized, creating a dual stigma (Ben et al., 2017).

Further Considerations and Implications for Practice

While an evidence base for trauma-informed systems changes and interventions grows, this article can offer both immediate implications for practice as well as further consideration and locations for inquiry. Conceptually, trauma-informed SUD services should rely heavily on the theory and practice of other humanistic paradigms, notably harm reduction and patient-centered care. Harm reduction “refers to interventions aimed at reducing the negative effects of health behaviors without necessarily extinguishing the problematic health behaviors completely” (Hawk et al., 2017, p. 1); it aligns well within trauma-informed care in that both highlight the need for collaborative and equitable relationships, and as well as a return of the control of the part of the service utilizer. Harm reduction methods were recently named as the public health model of choice by the Biden administration to limit overdoses and other harms associated with substance use (joebiden.com, 2020). Patient-centered care is a framework that highlights the needs of individual clients within sometimes overwhelming health systems; it aligns well with the trauma-informed paradigm because both highlight the need for easy access to systems as well as individual interventions based on patient need and vulnerability (Marchand et al., 2019).

Ideas for practice transformation can vary widely, and yet there are some immediate actionable steps that nurses can take to transform their practice. First and foremost, nurses must begin to use nonstigmatizing and more clinically accurate language to discuss clients who use substances and those who have SUDs. Second, all nurses (regardless of practice location, level of education, etc.) can interrupt harmful narratives that exist within health care about people who use drugs. For example, most nurses understand the concept of a patient who is “drug seeking.” We suggest that nurses immediately interrupt these narratives, both internally and externally and find ways to allow even the most challenging patients to feel safe. Interruption of this narrative may look like correcting a coworker who uses this term and offering data on the ways in which trauma creates a neurobiological vulnerability to addiction, or, attending specifically to the psychosocial needs of the patient in question and reminding said patient that there are some medications that disallow safety, such as opioids or benzodiazepines and that a denial of these medications is rooted in a desire to keep the patient safe.

The authors suggest the following examples of places we need to inquire in order to provide more deeply informed trauma-informed services within SUD services: patient experience of urine drug screens, withdrawal management setting strategies for psychological safety, patient experience of difficult conversations with providers and staff (e.g., referral to a higher level of care or denial of controlled substances). Moreover, the use of community participatory research is needed to most fully understand the needs of people using drugs and accessing SUD services.

Conclusion

As we enter into a new period of understanding SUDs based on the neurobiology of trauma and addiction, we must equally transform our services to meet the needs of people who use drugs and people who seek our support to cease drug use. We will need to address stigma, change how we think about (and refer to) people who use drugs, and understand the ways in which structural violence contributes to SUDs. SUDs services must forgo previous treatment paradigms, which relied heavily on harmful and reductive beliefs regarding both the cause of SUDs and the appropriate interventions, which were often based on models of accountability and criminalization despite a lack of evidence. Substance use services and the nurses who strive to provide compassionate, judgement-free services to clients with SUDs can and should embrace the trauma-informed paradigm.