Abstract

The United States is an outlier in juvenile sentencing practices, often subjecting youth offenders to extreme and lengthy punishments. While the Supreme Court over the past two decades has been slowly narrowing the nation’s use of such sentences against children through a series of cases known as the Miller Trilogy, this progress came to a sudden halt in the 2021 case of Jones v. Mississippi. However, in surprising turn of events, the Supreme Court’s recent national display of restraint has not stopped sentencing reform efforts in the states. Contrary to the current Supreme Court, states in the U.S. have preserved the values and precedents set by the Court in the Miller Trilogy. Today, over half of the states in the United Sates have abolished the harshest sentence a child can receive through a combination of legislative and judicial efforts that prevails despite political differences. The trends in recent years of state reform display a renewed hope for the status of juvenile sentencing in the face of present Supreme Court inaction.

Chapter One: Introduction and Purpose of Thesis

Adolescence is a period of life which many remember as a vulnerable time of their lives. People may make questionable and reckless decisions that they would never repeat as they mature and become adults. Young people often experience mental health issues, but there are not adequate societal structures in place to manage one of the most at-risk groups of youth. The lack of support has severe consequences for juveniles in the criminal justice system who can be harmed by current sentencing practices.

Consider a hypothetical teenage boy, James. James has not grown up with an affluent upbringing. Where he lives, extra-curricular school programs are underfunded and he is likely to spend time in the company of his peers smoking and drinking, as millions of teens do every year. . In his city, 1 in every 119 people will be a victim of violent crime, and 1 in 25 people will be victims of a property crime. In addition, James and his friends consume media on television and in video games that cause him to believe that carrying a gun with him wherever he goes is the only way to keep himself safe. He is invited by a friend to drive around with a man both older than and unfamiliar to James, to smoke marijuana. Under the influence of these drugs, a heated argument breaks out in that confined space. When the stranger in the driver’s seat that James just met reaches down for something, James’ friend shouts that he has a gun and demands that James use his own weapon to shoot. Faced with what he thinks is a life-or-death situation, James draws his weapon, and shoots and kills the driver. When he is arrested, the state determines that for his crime, he must be tried as an adult and thus subject to the same penalties if he is found guilty. The jury, however, does not believe his story. He is found guilty and through chance and chance alone, James was born in one of the 23 states that still permits juveniles to be sentenced to a sentence of life without parole for the crime of homicide, including those murders like James’ that weren’t premeditated. He is sentenced to life without parole and spends the remainder of his life in prison for a crime he committed as a legal child.

Though James’ is not real and never endured a life behind bars for this crime, his story is loosely based on the true story of a Tennessee teenager who almost faced the same fate and whose story and court triumph will be discussed later in this thesis. Yet, the first important thing to note is that James’ story could happen to any teenager in America still residing in states where lengthy juvenile sentencing remains acceptable practice in the criminal justice system. The United States Constitution promises protection for every citizen against “cruel and unusual punishment.” Yet when an adolescent’s mind has yet to finish maturing, sentencing them to juvenile life without parole raises profound legal questions. Some argue that juvenile life without parole is indeed cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. Although the United States Supreme Court has not taken this position, it is noteworthy that some state courts and legislatures have recently begun to revisit the question of juvenile life without parole.

The Definition of Juvenile Life Without Parole and Its Role in the U.S. Juvenile Justice System

Juvenile life without parole, often referred to in scholarly works as JLWOP, is a sentencing scheme that 1) requires a sentence of life rather than a term of years, and 2) the person sentenced to be under eighteen years of age,6 the age at which a person is considered a legal adult in the United States. Juveniles are subject to life without parole sentences when they undergo the process of transfer, a mechanism in the American criminal justice system that allows for a child who commits serious and violent offenses to be moved from juvenile court to the adult criminal justice system for their prosecution. Many prosecutors and prosecutorial agencies support the transfer of some juveniles to adult court is because they believe the process serves as a specific and general deterrent that will dissuade the defendant and the general population of youth from reoffending or committing severe crimes. Nevertheless, some research studies have determined that juvenile transfer is actually associated with slightly higher rates of recidivism amongst the population of those juveniles prosecuted through the adult court system. By 2010, juvenile life without parole sentences could only be given to those juveniles found guilty of homicide offenses.

Children sentenced to JLWOP are in fact sentenced to die in prison for crimes they committed in their youth. While the Supreme court banned automatic life without parole sentences for juveniles sentenced as adults, for the same and similar violent crimes, youth in the United States who are transferred to adult court may face a different situation. These juveniles may be sentenced to lengthy automatic life with parole sentences and de facto life sentences of fifty years or longer for crimes that they committed when they were under the age of 18. Many argue that these sentences are functional equivalents of life sentences for juvenile offenders. Studies have shown that incarceration severely shortens life expectancy, with some estimates arguing that for every year of prison, two years are shaved off of an inmates’ life expectancy compared to the national average. A negative linear relationship between life expectancy and prison time was also found in a 2013 study with data taken from New York State parole administrative databases spanning the years 1989 to 2003. Researcher, Dr. Evelyn Patterson found that five years in prison increased the odds of death by 78% and took ten years off of their expected life span at the age of thirty. Both of these examples indicate the bleak prognosis for youth incarcerated for decades. Notably, the study also indicates that sentences of forty, fifty, and sixty years are considered by some to be the functional equivalent of life sentences for these juveniles because they spend the majority of their years in prison. Consequently, their chances of dying in prison is a more certain reality.

It is important to mention that of 197 countries, the United States is the only country in the entire world that sentences its children to life without parole. In fact, sentencing children to die in prison is condemned by international law. Article 37(a) of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international human rights treaty setting out the civil, social, economic, political, health and cultural rights of children states that, “No child shall be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below eighteen years of age” functionally outlawing the practice as a matter of international law. The United States, a member state of the United Nations signed onto the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, yet every year in the United States, juveniles as young as the age of thirteen are subject to JLWOP sentences for their crimes.

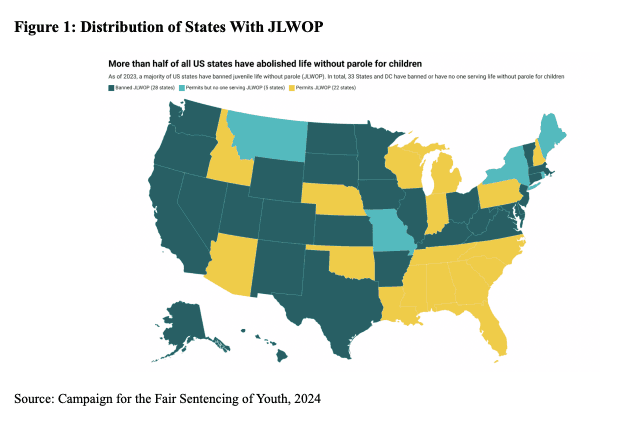

Today, only twenty-eight states have banned the sentencing practice of life without parole for juvenile offenders. Of the remaining twenty two states, the majority are concentrated in the southeastern United States, yet the state that houses the highest number of youths serving JLWOP sentences is Michigan. An additional five states, New York, Rhode Island, Maine, Missouri, and Montana, have yet to ban the practice, but have no incarcerated individuals residing in the state and serving this sentence (See Fig. 1). Nevertheless, according to the Sentencing Project, a prominent activism organization that advocates for decarceration and fair sentencing, according to 2020 data, 1,465 incarcerated individuals across America are serving JLWOP sentences. So long as life without parole exists as a sentencing option for children, this number only has the potential to increase.

The Important Differences Between Adult and Juvenile Brains

That “young and dumb” reputation, popularized in media and anecdotes exists for a very scientific reason that undermines the rationale for the practice of juvenile life without parole. While juveniles are certainly not dumb, they lack fully developed reasoning and processing skills, and practitioners and scientists largely agree that the juvenile mind processes things differently than an adult’s mind would in several key aspects. These professionals that these important differences should make a juveniles less legally culpable for their actions than adult offenders. The consensus among neuropsychiatrists today is that the adolescent brain lacks a fully developed sense of impulse inhibition until the age of twenty-five. This is well above the age of thirteen, the earliest that a juvenile can be deemed old enough to serve a life sentence without parole for their actions, actions which were likely influenced by an underdeveloped perception of impulse control and consequences. This is because teenagers’ prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that prompts logic and reason in decision making, is less developed than it is in adults. Instead, in situations of high pressure, they rely on the limbic system, a group of systems in the cerebrum of the brain that command the intensity of emotions including fear, anger, and the fight or fight response. As a result, teens are more susceptible to quickly become angry, experience intense mood swings, and make decisions based on “gut” feelings that can all influence the elements of a crime when it is committed.

To prove guilt in criminal justice proceedings, two foundational elements must be established to demonstrate culpability, the actus reus, the guilty act, and mens rea the guilty mind. Mens rea requires that the defendant knowingly and intentionally, to a rational mind, committed a criminal act. Yet, given that juveniles’ brains are not yet fully developed, fundamentally lack a proper impulse inhibition, and subconsciously rely on the limbic system that triggers actions on “gut” feelings, under these legal definitions their ability to have the same mens rea as adult offenders is substantially reduced. Therefore, a widely accepted defense against the attempt to prove mens rea, is that juveniles possess what is known as diminished capacity. Diminished capacity is defined by the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University as the “theory that a person due to unique factors could not meet the mental state required for a specific intent crime”24 under which would fall the crime of homicide, the only crime for which a child can receive the sentence of life without parole for.

In fact, the findings of many psychological studies have implied that changes in the brain’s function that allow for future rational decision making rely markedly on maturation alone.25 This implies that it is simply a matter of a few years’ time for many juvenile offenders to develop the decision-making abilities that could alter entirely their behaviors in the kinds of situations that led to their imprisonments of life without parole. It is for this reason why many psychologists, activists, and legal professionals believe in a child’s increased capacity for change and rehabilitation compared to that of a similarly situated adult offender. Additionally, that would make sentences like JLWOP both inhumane and unnecessary for them. Life without parole sentences exist to incapacitate those that the criminal justice system believes to be a permanent threat to society, and opportunity for parole is revoked due to belief by a judge or jury that the defendant is permanently incorrigible. However, the concept of permanent incorrigibility for youth directly contradicts the previously mentioned scientific evidence and is widely disputed due to the intersection of neuropsychological study of brain development and population studies on incarcerated juveniles.

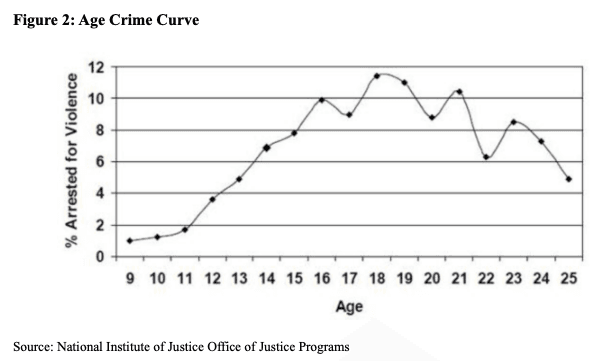

What is most commonly referred to as the age-crime curve (See Fig. 2) can be found consistently across incarcerated populations across the nation and in Western populations as a whole.26 These curves demonstrate that offending amongst juvenile populations tends to increase from early childhood, peaks between the ages of fifteen and nineteen, and decrease in their early twenties.27 By the age of twenty five, rates are often at about half of what they were at the peak of the curve.28 According to research conducted by criminologists Jeffrey T. Ulmer and Darrel Steffensmeir of Pennsylvania State University, this age-crime curve trend occurs for two primary reasons. Firstly, twenty-five is widely agreed upon to be the age at which the brain stops developing, and changes in the prefrontal cortex that affect risk-taking, impulse control, emotional maturity, and rational decision-making fully form these elements in the adult mind.29 Secondly, natural life-course events such as employment, increases in income, marriage, and children become increasingly pertinent to the mind with age. Events such as these make the potential consequences of committing a crime far more riskier and unappealing, and can act as a age-related deterrent to criminal activity in the mid-twenties.30 These factors contribute to a natural drop in likelihood to reoffend, and given that the brain of a teenager who has been incarcerated in their youth has yet to finish developing, they retain malleability for reform during their time in prison. Thus, the idea that a child is “permanently incorrigible,” when they retain a capacity for change and decreased likelihood for re-offense if they commit a crime during their child due to natural biological changes is largely unfounded. Critics argue that to have this idea reinforced by the pervasiveness of juvenile life without parole sentences in the United States is to directly defy what science has found to be true of youth and their capabilities for reform.

The History of Juvenile Justice Policy and Life Without Parole in the U.S.

The state of criminology’s views on the brains of juvenile delinquents, however, was not always so forward thinking and forgiving, and it informed many of the sentencing schemes juveniles are presently subject to, including juvenile life without parole. Prior to much of the recent research that informed present day knowledge on the deficiencies of the juvenile brains, many people characterized these children as a new, dangerous threat named by criminologists as “superpredators.” In 1995, criminologist and Princeton professor, John DiIulio gained national attention when he published an article coining the term “superpreadator” to describe a type of remorseless child criminal who would overrun the country and increase crime rates. Though this theory was purported when crime was at an all-time decade low,31 DiIuilo argued that by 2010, if criminal justice policy did not impose harsh penalties, the number of juveniles in custody would increase threefold. This theory was reinforced by criminologist, James Fox, who stated that “Unless we act today, we’re going to have a bloodbath when these kids grow up.”32

The practice of sentencing juveniles to life without parole began in the “tough-on-crime” era of the 1970s, a time during which it was a priority of lawmakers to reduce rising crime rates.33 However, between the 1970s and 1990s, the youth was often considered and accounted for in court by a defense of infancy, requiring the state to prove that a child is capable of forming mens rea and to overcome the presumption that a child lacks the mind to consider the wrongfulness or consequences of their criminal act.34 Though this defense was not accepted in juvenile courts, it held great weight and value in the defense of children who were accused of committing violent crimes.35 However, the statistically significant increase in media coverage and sensationalism of juvenile violent crime in the 1990s, which resulted in a rising level of fear among the public, caused the adoption of more punitive juvenile crime.36 With the perception of this alleged looming threat, legislators advocated for a “tough on crime” approach in their campaigns and their lawmaking. Across the country, legislators passed new statutes that broadened the crimes for which a juvenile could be transferred to adult court, and thus, subjected more children to adult sentencing schemes such as juvenile life without parole.37 Criminologists Fox and DiIuilo, founders of the theory, later admitted that the prediction of a juvenile superpredator epidemic turned out to be wrong. They now acknowledged that their suprepredator myth “contributed to the dismantling of transfer restrictions, the lowering of the minimum age for adult prosecution of children, placing thousands of children into an ill-suited and excessive punishment regime.”38

Though the United States remains the only nation in the world to have retained the practice of sentencing juveniles to life without parole, limitations have been placed upon after reforms that occurred in the last two decades. Prior to 2005, children as young as twelve were subject to these adult sentencing protocols imposed on them out of fear driven by the super predator myth. As a result, children as young as sixteen years old could be sentenced to the death penalty. Yet between 2005 and 2012, the severity of punishment for juveniles would diminish from the possibility of the death penalty to juvenile life without parole exclusively for crimes of homicide. While this is still behind the standards and ethics of justice held by the rest of the world, the three Supreme Court cases that contributed to this progress are significant for the way they changed the American perspective on juvenile sentencing and for the way it has influenced state judicial action towards reform.

A Brief Overview of the Miller Trilogy Caselaw and Juvenile Life Without Parole

Perhaps the most significant series of juvenile justice cases affecting life without parole are Roper v. Simmons (2005), Graham v. Florida (2010), and Miller v. Alabama (2012). Together these cases are commonly known as The Miller Trilogy of cases, and they transformed the landscape of juvenile sentencing in the United States. All of these cases rely heavily on portions of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution bars the government from imposing “cruel and unusual punishment” on a defendant.39 The term “cruel and unusual” has evolved over the course of centuries of court cases and legal proceedings. Today it refers to punishment that is significantly harsher than punishments inflicted on similar crimes. In Solem v. Helm (1983) a 1983 Supreme Court case, this definition was expanded to encompass the disproportionality of a sentence for its crime.40 The latter is especially pertinent in the Miller Trilogy of cases, as proportionality of sentence is a key factor in determining what is an acceptable punishment for youth who commit similar crimes to adults with fully-developed brains.

The Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution guarantees a right to “due process” of law, the right to every citizen to be afforded equal procedures of law before their “life, liberty and property” can be deprived.41 The Due Process Clause is also the guarantee protecting individuals from cruel and unusual punishment imposed by state governments through what is known as the incorporation doctrine, a mechanism that allows parts of the first ten amendments to the Constitution are made applicable to the state governments’ actions. Both of these constitutional amendments will be paramount to understanding the oral arguments and the Supreme Court’s decisions in the Roper, Graham, and Miller cases to be discussed further detail later in this thesis.

The first of these cases, decided in 2005, after seventeen-year-old Christopher Simmons was sentenced to death for the murder of Shirley Crook and battled his case in appeals for nearly ten years, Roper v. Simmons (2005) determined that the death penalty for minors was unconstitutional.42 The decision overturned a 1989 case Stanford v. Kentucky (1989) that relied on a finding that a majority of Americans did not consider the death penalty for minors to be “cruel and unusual.”43 In Roper, however, The Supreme Court found the execution of minors to be unconstitutional,44 a historic Supreme Court decision changing the standard of juvenile justice and justice in America and a whole. The Court’s decision in Roper v. Simmons would mark one of the first cases to consider, and most importantly question, the role of evolving standards of decency, society’s changing views informed by social and scientific factors, in it criminal jurisprudence. The lives of 72 death row inmates sentenced to their demise as minors, including defendant Christopher Simmons, were saved with the ruling of that Supreme Court decision.45 The press and the legal community noted that the ruling advanced the civil rights of minors sentenced to death, spurring additional advocacy and research that would lay the foundation for the remainder of the Miller Trilogy cases to follow in that decade.46

Roper’s impact on other juvenile sentencing schemes raised additional questions in the years following its ruling. In 2009, the case of Terrence Graham, convicted of armed home burglary and sentenced to life without parole by a Florida state court, came before the Supreme Court. It was the first case after the landmark ruling of Roper v. Simmons that reached the Supreme Court, and to apply the same Eighth Amendment arguments presented in Roper v. Simmons. Upon his appeal, Graham and his attorneys argued that the imposition of life without parole on a juvenile violated the Eighth Amendment.47 The Supreme Court’s ruling for Graham in this case would be the first to significantly restrict the application of JLWOP sentences, and the first to apply Eighth Amendment principles to a sentence other than execution for juveniles that was left constitutional for adults. Once more, the Supreme Court’s decision in this case would rely on evolving standards of decency, with a renewed emphasis on and inclusion of scientific findings of the differences between adult and juvenile brains in the majority opinion of Justice Anthony Kennedy.48

Miller v. Alabama (2012) would further build upon the progressive curtailing of harsh juvenile sentencing brought about by cases Roper and Graham. Argued and decided in 2012, Miller v. Alabama handled the case of Evan Miller and Colby Smith. Miller, at the age of fourteen, and Cole brutally murdered victim Cole Cannon by beating him with a baseball bat and lighting his trailer on fire. Miller was then transferred from his county’s juvenile court and processed through the criminal court to be tried and sentenced with the crimes of capital murder and arson, for which he was subject to a mandatory life without parole sentence triggered by the state of Alabama’s sentencing scheme which required those convicted of the crime of capital murder in the criminal court to a mandatory life sentence, regardless of their age.49 Miller challenged the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, which affirmed the lower court’s decision. The Supreme Court agreed to hear Miller’s case which posed the question of whether the mandatory imposition of a life without parole sentence on a juvenile violated the Eighth Amendment’s protections against cruel and unusual punishment. Notable for the way it built upon the foundations of legal reasoning in Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida, the decision of the Supreme Court in Miller would expand protections for juveniles, barring mandatory life without parole sentences from being given to children.50 Miller v. Alabama marked a new and noteworthy area or progress in challenging severe youth punishment in that it was the first case to scrutinize mandatory sentencing schemes for youth and the second landmark case to narrow the application of juvenile life without parole.

Over time, however, the composition of the Supreme Court changed from a court with a majority of justices who distinguished between juveniles and adults with respect to Fourth and Eighth Amendment claims to a more conservative court that did not. This conservative court will be shown to have vastly different ideas on the role of the Court in defining juvenile justice policy, the value of science and evolving standards of decency in deciding a case, and on adhering to the precedents set by Roper, Graham, and Miller. The justice who pioneered progress and authored all three Miller Trilogy opinions, Anthony Kennedy, retired from the Court in 2018,51 and three other justices had either retired or passed away by the year 2020, when the Supreme Court heard it’s fourth landmark JLWOP case, Jones v. Mississippi (2021).

In stark contrast with the Miller trilogy cases, the majority on the Supreme Court in Jones refrained from narrowing the application of JLWOP sentences. The case derived from the crime of appellant, Brett Jones who stabbed his grandfather to death at the age of fifteen.52 A clarification on Miller in a 2016 Supreme Court case stated that Miller only allows the imposition of JLWOP in the cases of “those whose crimes reflect permanent incorrigibility.”53 After a dispute regarding whether the consideration of this factor in court proceedings would entitle Jones to parole, the Supreme Court heard Brett Jones’ case. Though it was completely within the power of the Supreme Court to take another step forward towards the abolition of a sentencing structure that has been condemned by the rest of the world in the fashion of their predecessors, the Supreme Court ruled against Brett Jones.54 Furthermore, it ruled against even increasing the standard of protections offered to juvenile offenders to ensure that the sentence can be rarely used.

Thesis Purpose and Plan

This thesis intends to establish that while the Miller Trilogy was not without its flaws, it set forth a clear direction for the future of JLWOP in the United States. These cases also recognized the importance of scientific findings of adolescent brain development and the way they should factor into youth sentencing. The thesis will also argue that Jones v. Mississippi is a definite outlier for the Supreme Court, which has previously prioritized the safeguards for youth in sentencing, and that Jones represents a distinct deviation from the precedents the Supreme Court has historically held in high regard. Additionally, this thesis will argue that Jones v. Mississippi is the death of evolving standards of decency in Supreme Court Eighth Amendment cases, and is therefore a step back for a potential future of abolition for juvenile life without parole sentences. In order to provide a thorough understanding of why this is and where hope for abolition lies in the wake of a changing stance on JLWOP from the Supreme Court, this thesis will examine three things. Firstly, it will examine the oral arguments and conclusions of the Supreme Court in the Miller Trilogy of cases, the progress it spurred, and the way it would influence future federal and state juvenile life without parole policy through a mixture of original case analysis and academic literature review. To highlight the contrast in the Court’s legal reasoning, adherence to precedent, and value for evolving standards of decency such as scientific findings and social leanings between The Miller Trilogy and Jones v. Mississippi, this thesis will do the same for Jones. In pointing out the ways in which the federal Supreme Court has changed its jurisprudence, and examining the dangerous implications that accompany the conclusions 23 made by the Supreme Court in this case, the first primary argument of this thesis is that the United States is unlikely to see the abolition of JLWOP in the near future through federal judiciary action due to the ideological priorities of the Supreme court’s current members.

This is not to say there is no hope for reform. In fact, the second primary argument that this thesis will make is that in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent inaction on the issue, initiatives by the states over the last decade indicate an increasing potential for abolition by the states well before JLWOP can be abolished or further restricted federally. This thesis will demonstrate that patterns in the more progressive spirit of the Miller Trilogy have continued to live on in the actions of state legislatures and courts, continue to rely on the precedents set by the Miller Trilogy to narrow and even abolish disproportionately lengthy sentencing for juveniles.

The analysis will rely upon case studies of two states that have changed their youth sentencing policies. Connecticut and Tennessee are chosen due to their position on opposite ends of the political spectrum. Connecticut is a liberal state whose approach to these policies is similar to that of the Supreme Court when deciding The Miller Trilogy. On the other hand, Tennessee’s policies are more like those favored by the conservative Court in Jones. Two cases and two bills across these two states will be analyzed and examined as a part of this case study research. Before the two senate bills were introduced in Connecticut, State v. Riley was a 2015 case in which the Connecticut Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether a life sentence without parole may be imposed on a juvenile homicide offender in the exercise of the sentencing authority’s discretion after Miller v. Alabama was decided. The eventual ruling of the case by the Connecticut Supreme Court’s majority provides valuable commentary on the ethical reasoning and legal direction many courts across the country were taking post-Miller, deciding that the state’s present interpretation of Miller was “unduly restrictive.”55 A probe into the legislation that followed, Public Act No. 15-84, S.B. 952 will find further similarities with the approaches taken in the Miller Trilogy by the Supreme Court.

Though a number of states have yet to ban JLWOP sentences through legislative action such as Connecticut, other states have sought to reduce harsh juvenile life sentences and revive Miller Trilogy values post-Jones through court action. This approach is exemplified by the 2022 case of the State of Tennessee v. Tyshon Booker (2022). Despite the narrow interpretation of the 8th Amendment and discarding of Miller Trilogy values in the most recent Jones v. Mississippi (2021) case, the Tennessee Supreme Court relied on the broad construction and increasingly liberal arguments of the Miller Trilogy to decide on this case. The court acknowledged in their ruling that crucial Miller Trilogy principle that “youth matters in sentencing” and argued that extreme sentencing must be “imposed only in cases where that sentence is appropriate in light of the defendant’s age.”56 Supported by polling research conducted by the Pew Research Trust and Data For Progress on opinions surrounding extreme sentencing for youth, the findings from these case studies will reveal that Americans across the with different political preference support less restrictive policies so that children will not spend their lives in prison for crimes they committed in their youth. This is a factor that both supports the driving forces behind the states’ sentencing reform and that indicates a potential for further sentencing reform in upcoming years.

Finally, this thesis will review policy suggestions and potential constitutional challenges that can be pursued to eliminate the practice of juvenile life without parole throughout America. Drawing on a range of academic sources, suggestions for possible mitigation efforts and constitutional challenges against life sentences for juveniles are explored. Additional research from various national organizations and social scientists on interactions between evidence-based policymaking and public opinion will be used to build upon these suggestions to create potentially viable policy solutions.

The nation’s history and the federal government’s adherence to continuing JLWOP demonstrates an overall lack of belief in its youth, and of the rehabilitative capabilities of a justice system that is not entirely retributive. However, this thesis will also shed light on the changing tides of thought in America away from the lengthy detention of juveniles, towards reform. In addition, the thesis will argue that the likelihood for total abolition JLWOP lies in the actions of the states, and it will provide recommendations and constitutional challenges to this sentence and others like it for those lawmakers and legal professionals whom juveniles facing disproportionate sentencing rely upon.

Chapter Two: From Atkins to the Miller Trilogy

In the United States, the function of the Supreme Court through its power of judicial review is not only to interpret and uphold the Constitution but to do so in a way that ensures the promise of equal justice for all under the law. In an early and consequential case, the Supreme Court recognized its power of judicial review in 1803 in Marbury v. Madison.57 The ruling upheld the Court’s power to declare laws in violation of the Constitution. Over time, the Court would declare laws unconstitutional in the area of criminal. Notably, the Bill of Rights provides guarantees for defendants against any state action that may violate their rights to fair trials and sentencing. Amendments Five through Eight of the U.S. Constitution all provide protections for criminals, including those sentenced and incarcerated under the age of eighteen. Only recently has the Court applied some of these constitutional protections to questions pertaining to juvenile justice.

In the tradition of the Supreme Court’s practice of abiding by stare decisis, the cases of the Miller Trilogy set a clear and predictable progression in juvenile sentencing, with each case building upon the legal reasoning laid of prior cases, and narrowing the extent to which minors could be subject to extreme punishment. Contemporary legal scholars John R. Mills and his coauthors agree that the Miller Trilogy marked transformational changes in the criminal justice system but also in Eighth Amendment legal theory and application.58 As this chapter will explain, both the oral arguments and rulings of the Miller Trilogy signified the important way in which social science inherently can inform our understanding of the meaning of cruel and unusual punishment as applied to juveniles. This line of case law was interrupted when the Court decided Jones v. Mississippi, a case that adopted more punitive standards for juvenile punishment.59

Aktins, Diminished Capacity and Evolving Standards of Decency

It is important to understand the reasoning provided by the affirming and dissenting judges in the Miller Trilogy and the consequences for the subsequent Eighth Amendment cases. As previously stated, relying upon and abiding by the precedent set by similar and applicable cases that had previously come before the court is common practice by courts and fundamental to maintaining the tradition of stare decisis that guides judges in their decision making. An earlier case of the most significance for the Miller Trilogy and excessive juvenile punishment was Atkins v. Virginia (2002).60

In 1996 petitioner Daryl Renard Atkins was convicted of armed robbery, abduction and capital murder. For his crimes, he was arrested and brought to trial, and he underwent a psychological evaluation that revealed Atkins suffered from mental disability. Despite these findings being brought to light during the trial by the expert defense witness who conducted the evaluation, the jury found Atkins guilty and sentenced him to death. Even after this information of Atkins’ diminished mental capacities was presented to the jury in a second sentencing hearing, they again sentenced him to death.61

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari to Daryl Atkins, agreeing to hear his legal challenge that sentencing the mentally disabled to death was unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment’s cruel and unusual punishment clause. The court, in a 6-3 ruling authored by Justice Stevens, agreed with the case brought by Atkins,62 basing its reasoning on various grounds relevant to the discussions of Roper, Graham, and Miller. One of the primary reasons why the court made the determination to firstly, grant a writ of certiorari in this case is in part due to what Justice Stevens describes as a “dramatic shift in the state legislative landscape that has occurred in the past 13 years,”63 namely that some states had outlawed the death penalty. This is particularly significant because it demonstrates the Supreme Court’s acknowledgement of evolving moral and legal standards in the states as a determining factor in the acceptance and decisions made in this case, something that can be seen throughout the Miller Trilogy of cases. This reference to state evolving standards is noticeably absent from Jones. The court did not limit this this application of the change in the states to their decision to grant cert, but in their decision to bar the application of the death penalty on mentally disabled individuals.

Stevens cited precedent from the previous Warren Court that set the tone for the Miller Trilogy’s approach to juvenile life without parole in a quote that states, “The basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment is nothing less than the dignity of man . . . The Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society."64 Other rationales presented in the Court’s opinion regarding the unconstitutional imposition of the death penalty for the mentally disabled include the concept of the proportionality of a sentence in relation to the then existing mental state of the defendant. Additionally, the majority in Atkins identified several principal aspects of the mentally disabled described by both modern child psychologists and the Court in the Miller Trilogy’s decisions. These include “significant limitations in adaptive skills such as communication, self-care, and self-direction;”65 the tendency of these individuals to “often act on impulse rather than pursuant to a premeditated plan; and the likelihood that in group settings they are followers rather than leaders.”66 The Supreme Court in Atkins would associate all of this with the concept of “diminished capacity,” the theory that due to the unique qualities of a mentally disabled person’s mental state, they cannot meet the mental state required for a specific intent crime. The origins of these concepts in Atkins are crucial to understanding their reappearance in the Miller Trilogy, specifically the standard they set for the court’s rulings on juvenile sentencing.

Miller Trilogy Oral Arguments

The oral arguments provided by the attorneys of the victorious parties in the Miller Trillogy, beginning with the case of Roper v. Simmons, play a vital role in the formation of a definition for “cruel and unusual punishment” for juveniles, and of a definition the “evolving standards of decency” so crucial to understanding the departure taken later by the Supreme Court in Jones v. Mississippi. Contained in the three oral arguments and rulings of Roper, Graham, Miller, and Jones, are three factors lending themselves proving evidence of cruel and unusual punishment and evolving standards of decency. The first is the comparison of foreign and domestic criminal justice, indicating that the United States is an outlier due to its extremely punitive youth sentencing. The second factor is the prevalence of the reasoning that the direction of domestic of policy changes, growing sentiment from the states embodied in judicial and legislative initiatives, indicate evolving standards of decency. Additionally, scientific findings drawn by many of these notable institutions and organizations are often made front and center in the determination of the cruelty of life without parole and the death penalty. The use of these scientific findings is the third factor across all three cases used to advocate against death and JLWOP sentences because the science supports the reduced culpability of youth and a theory of the disproportionality of lethal or life sentences. The combined trend of these three factors being prevalent across all three cases scientific, is particularly notable, however, for the way they would and continue to align with the circumstances surrounding juvenile life without parole in a post Jones world.

The successful arguments in the Miller Trilogy line of cases are rooted in the applicable parallels between the legal concepts put forward in Atkins in defense of mentally disabled criminals, and also the unique conditions of juveniles and the how the nation and world has responded to them in criminal justice policy. The case in which comparative criminal justice policy was relied upon most heavily was Roper v. Simmons, the case in which the respondent, convicted juvenile murderer Christopher challenged his death penalty sentence. One of the primary reasons provided to the Supreme Court in the oral arguments delivered by Christopher Simmons’ attorney was that nowhere else in the world was the death penalty legal for a minor.67 Rebutting Justice Scalia’s questions of whether the United States should yield to the rest of the world, simply because it has abolished the death penalty for juveniles, the respondent’s attorney responded that there exists “a constitutional test that looks to evolving standards of moral decency that go to human dignity.”68 The attorney emphasized the fact that the United States was the only remaining nation in the world to execute those who committed crimes as children, a significant fact that is relevant to the determination of the constitutionality of a criminal punishment. Though no other case after Roper relied heavily on comparative juvenile justice policy, at this moment in time, the circumstances of JLWOP sentences are consistent with arguments supporting the abolition of the death penalty for juveniles in Roper was argued.

A frequent strategy utilized by the attorneys in the Miller Trilogy and Jones oral arguments focused on the situating the evolving standards of decency in juvenile sentencing in trends of domestic law and policy change. In 2004, when the case of Roper v. Simmons was brought forth to the court, thirteen states had abolished the death penalty for all convicted criminals.69 A 2004 Juveniles News and Developments article on the Death Penalty Information Center reported that 31 states had banned the practice of executing juveniles prior to the oral argument date in October,70 and a further 14 states had laws requiring the minimum possible age of execution ne 18 years of age.71 The secondary argument provided in Roper that would reappear in future debate on disproportionate juvenile punishment highlighted state legislation as an indicium of evolving standards of decency. As the attorney for respondent Christopher Simmons made clear in his argument, no state which enacted age-specific amendments to their death penalty laws lowered the age, and no state that barred the death penalty for children, reinstated it.72 “The movement, addressed by the Court in Atkins, has all been in one direction,” the attorney stated. Pairing this trend with the precedence set in Atkins with scientific support, the respondent’s conclusion was that the combination of these factors created “scientific, empirical validation for requiring that the line (for the death penalty) be set at 18.”73 In other words, there was both legislative action and institutional support that was informed by the concept of evolving standards of decency.

Four years later, in Graham v. Florida, following the precedent established in Roper, a very similar argument can be observed in the case presented by the petitioner. In 2009 at the time of oral argument, all but five states in America permitted juveniles to serve life without parole sentences,74 which can be perceived as overwhelming support for the JLWOP sentence in all circumstances. The Roberts court affirmed this notion with their own on this trend, indicating an appreciation of the sentence from the states, “the fact that it has been allowed for so long and imposed so rarely, as the States themselves have admitted, is strong evidence of societal consensus.”75 Nevertheless, Graham’s attorney acknowledged that states that primarily utilized the JWLOP sentencing only for the crime of homicide. The attorney for Graham took the point a step further and contended that it is instead evidence that this behavior from the states indicated the unusuality of the punishment, a necessary prong to prove that a sentence violated the protection from cruel and unusual punishment in the Eighth Amendment.76

When attorney Bryan Stevenson brought fourteen-year-old Evan Miller’s case to the Supreme Court in 2012,77 advocating for a ban on life without parole sentences for juveniles under the age of fourteen and mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles, he too focused on evolving standards of decency based on the states’ policies. Before Miller was decided, 39 jurisdictions allowed the imposition of life without parole sentences on children,78 During the oral argument, the Supreme Court’s conservative justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito used this statistic in their questioning of the petitioner. Justice Scalia in particular noted that because the enactment of such a punishment on juveniles was still possible in so many jurisdictions in America it indicated the states’ standards of decency. He said, “the American people, you know, have decided that that's the rule. They allow it. And the Federal Government allows it.”79 Though rebuffing this idea was no easy feat for Bryan Stevenson, he was still able to offer a point lending itself towards the standards of many states. Stevenson stated, “The States that have actually considered, discussed, and passed laws setting a minimum age for life without parole have all set that minimum age above 15. That's my primary argument. Thirteen States have done it; all of them except for one have set it at 18.”80

Present across all oral arguments of the Miller trilogy and Jones was the integration of scientific evidence to compel the court to reduce the severity of punishments that youth were receiving such as the death penalty and JLWOP sentences. Roper v. Simmons was argued on the heels of much of the scientific evidence mentioned earlier in this thesis that identified the inherent qualities of reduced culpability and potential for rehabilitation that juveniles possess. Attorney Waxman, arguing for criminal defendant Christopher Simmons described these pieces of evidence as changing “the constitutional calculus for much the same reasons the Court found compelling in Atkins,”81 which were essential to the proper interpretation of the Constitution in regard to the sentencing of juveniles. In Roper, the scientific evidence was not as perhaps developed as it is today, but the attorney for Simmons was able to persuade the court of several things. Firstly, he was able to confirm that juveniles have diminished moral capability, based on the research of the time that, and he argued that “here adolescents -- are less morally capable. They are much, much less likely to be sufficiently mature to be among the worst of the worst.”82 This second sentence additionally implies that the possibility of becoming “the worst of the worst” happens after this maturity is obtained at adulthood, presently supported by science, a concept supported by adolescent psychology83 In order to explain to the Court the factors that should inform a possible age-related spectrum of developmentally-driven culpability, Simmons’ attorney said, “every scientific and medical journal and study acknowledges that 16- and 17- year-olds are the heartland. No one excludes them. And what we know from the science essentially explains and validates the consensus that society has already developed.”84 Notably, this argument underscores the evolving standards of decency, and it pushes the idea of immaturity to the legal definition of adulthood, which is in many states is still currently placed at 18 years of age. Additionally, this declaration that the ages of 16-17 are the “heartland” of adolescence also aligns with the trend of crimes peaking at that age range in the age-crime curve.85 The age-crime curve, measuring the susceptibility towards criminal activity, reaches a peak around the age of 16 (See Fig. 2), consistent with both Christopher Simmons’ specific case and also the general youth population.86

The attorney for Terrence Graham also made important references to scientific evidence in the oral arguments Graham v. Florida.87 Though they did not feature as prominently, the science cited in the oral argument and opinions of Roper v. Simmons was used to support the petitioner’s argument in Graham, in the context of advocating for the ban of JLWOP sentences for those children who commit non-homicide crimes. The unconstitutionality of the penalty of life without parole for a child who has not committed a homicide was substantiated by attorney for the petitioner Bryan Gowdy, when he argued that the sentence is “cruel because of the inherent qualities of youth.”88 The “inherent qualities of youth” included those defined by scientists in scholarly articles published at the time, such as one published in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, that identified the existence of deficits in rational decision-making abilities and impulse inhibition in juveniles aged 11-18.89 Additionally, the attorney stated, “this sentence clearly falls on the line of being cruel because it tells an adolescent, for an adolescent mistake, you can never live in civil society.”90 The identification of an “adolescent mistake” rather than a general mistake implies that it is a separate kind of mistake from the kind that can be made as an adult due to these scientific factors, and highlighting the uniqueness of the mistakes that juvenile defendants make. To conclude his argument, Attorney Gowdy provided an answer rooted in in response to judges’ questions about whether in cases of juvenile sentencing the Court should adopt a categorical approach or one that would process juveniles and determine their culpability on a case-by-case basis. He stated, “Based… on what scientists have told us, the categorical approach is the most logical approach because we can't tell which adolescents are going to change and which aren't,”91 given the nuances of the adolescent mind development across that specific population of individuals.

Much in the same way as Attorney Bryan Gowdy relied on science to display the cruelty and disproportionality of JLWOP sentences, Bryan Stevenson, attorney for petitioner Evan Miller also offered scientific evidence up to the Court to prove that mandatorily sentencing a fourteen-year-old to juvenile life without parole was “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eight Amendment. Given the court’s reliance on these psychological findings in the previous two cases of the Miller Trilogy, Roper and Graham, he opened his argument by identifying the “internal attributes and external circumstances that preclude a finding of a degree of culpability.”92 Additionally, Attorney Stevenson laid these facts and the court’s recognition of them as a foundation for an argument which the court later accepted, namely, that the sentence of life without parole for juveniles may be cruel and unusual in certain circumstances, regardless of the manner of the crime. Of the Court’s decision he said,

these deficits in maturity and judgment and decision-making are not crime-specific. All children are encumbered with the same barriers that this Court has found to be constitutionally relevant before imposition of a sentence of life imprisonment without parole or the death penalty93

Once again central to a Supreme Court JWLOP oral argument was the stance that to impose such a sentence would be stripping children of their chance to rehabilitate when the science suggests that this is not only a possibility for them to do so, but a likelihood. Evan Miller’s attorney argued, “even psychologists say that we can't make good long-term judgments about the rehabilitation and transitory character of these young people”94 suggesting that the Court err on the side of caution and provide children with the benefit of the doubt in sentencing.

Across the Miller Trilogy, the combined trends of leveraging advancing scientific finding and forward legislative movement in these oral arguments are important. Those that the court were persuaded by would remain constitutionally significant for the definition of acceptable sentencing for youth. Aside from the strength they would garner from acceptance in the Supreme Court’s rulings, they would and continue to align with the circumstances surrounding JLWOP when Jones v. Mississippi was decided in 2021, and even in the present day.

Chapter Three: The Court’s Changing Jurisprudence from Miller to Jones

The Miller Trilogy Rulings

In agreeing with these specific points made by the attorneys during the oral arguments for the Miller Trilogy, the Supreme Court set forth legal precedent in each of their rulings in these cases, binding in future federal, state, and trial court cases, that became more accepting of scientific conclusions regarding the adolescent brain and appropriate juvenile sentencing standards. The conclusions in each of these cases shapes the acceptable punishments of youth convicts today, and the Miller Trilogy opinions laid out a blueprint for the interpretation of scientific evidence used by judges as they further defined cruel and unusual punishment for juvenile offenders. The discussion below will explore the noteworthy trends in the Supreme Court’s conclusions in the Miller Trilogy and their subsequent consequences for the law and youth sentencing practices.

Before the holdings and dicta of the rulings can be explored, it is necessary to examine the trends in the Court that decided them, namely, the makeup of those seated on it and their backgrounds. Five justices on the Supreme Court were present for the entirety of the Miller trilogy. Liberal-leaning Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer, consistently joined the majority by agreeing or concurring with the majority. Conservative-leaning justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia always dissented, and the fifth justice, often considered centrist, was Anthony Kennedy. The rest of the justices would join in with their input on juvenile sentencing after the decision in Roper. It is notable that in the decade during which all three Miller Trilogy cases were decided, the Supreme Court was not more conservative than the general America public that it served. A ten-year longitudinal study conducted by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) studied the makeup of the court and the shifts in the court’s political alignment based on its most centrist judge over time. Their study reported that in 2010, during the time between the Graham and Miller decisions, “with Kennedy as the median [justice], the court’s rulings put it in an ideological middle ground roughly halfway between Republicans and Democrats.” In addition, “the estimated ideological position of the court with Kennedy as the median falls almost exactly at the position of the average American.”95 Given the integral role played by societal norms and sentiments towards the interpretation of cruel and unusual punishment, the fact that the court’s political alignment was so similar to that of the public may have been a factor in their acceptance of these standards of decency offered to them by the scientific and legal communities advocating for diminished extreme sentencing for youth.

Of the Supreme Court’s majorities in these ruling there was one judge whose opinions and attitudes championed juvenile sentencing reform and cannot be overlooked in this analysis. Authoring the landmark cases of Roper and Graham, the first two out of the three Miller Trilogy opinions, the presence of Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court was central to the understanding of permissible juvenile sentencing and the establishment of the importance of “evolving standards of decency” to the understanding of the Eighth Amendment. During a time that many legal scholars would argue the political spectrum of the Supreme Court justices was far more prone to ebb and flow across their decisions in cases with different political impacts,96 Justice Kennedy was appointed to the Supreme Court by Republican conservative President Ronald Reagan in an effort to “to appoint only those opposed to... the 'judicial activism' of the Warren and Burger Courts,"97 whose decisions were regarded by conservatives as too progressive. Given this public promise, there is reason to believe Justice Kennedy was appointed out of belief that he would abide by these intentions when replacing the original nominee Robert Bork. In spite of this, Justice Kennedy’s opinions on the landmark Miller Trilogy demonstrated a considerable act of judicial activism, and a willingness to move outside of the boundaries of one’s political affiliation following his neutral interpretation of the Eighth Amendment, and its implication for juvenile sentencing schemes. Legal scholars who have analyzed his work, identify trends in his decisions, namely that “when Justice Kennedy was assigned to write a majority opinion, he wrote more often on the side of criminal defendants than for the government.”98 The presence of a figure with such a record on the Supreme Court during the processing of juvenile criminal cases notably left a more progressive impact on sentencing, as he was a consistently a staunch advocate for the rights of youth defendants.

The first of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinions was authored in the case of Roper v. Simmons and affirmed many arguments by Christopher Simmons’ lawyer (discussed previously in this chapter) during oral argument. These include the weight of international and state policies as indicia of evolving standards of decency as well as the importance of scientific evidence when structuring acceptable and constitutional juvenile sentencing standards. In response to the first point offered by Christopher Simmons’ attorney, the Supreme Court’s majority in Roper placed considerable value on the arguments calling for America’s international isolation in juvenile sentencing protocols to be a driving factor in determining the unconstitutionality of the death penalty for children. In his majority opinion, Justice Kennedy wrote, “Our determination that the death penalty is disproportionate punishment for offenders under 18 finds confirmation in the stark reality that the United States is the only country in the world that continues to give official sanction to the juvenile death penalty,”99 not only acknowledging America’s outlier status, but also affirming that this type of evidence offered in support of juvenile sentencing reform is both acceptable and constitutionally significant. In fact, evidence of a tradition of affirming this type of evidence is provided in the Roper decision following this statement: “Yet at least from the time of the Court’s decision in Trop, the Court has referred to the laws of other countries and to international authorities as instructive for its interpretation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of ‘cruel and unusual punishments.’”100 The statement both emphasizes the presence of a Supreme Court precedent that prioritizes the incorporation of international standards in the interpretation of the Eighth Amendment more generally and also extends that precedent to the Supreme Court decisions regarding juvenile life sentences.

The Supreme Court opinions in the Miller Trilogy also highlighted the importance of domestic policy changes in shaping the concept of evolving standards of decency in Eighth Amendment doctrine. Consistent throughout the opinions was an emphasis on the arguments offered to them comparing a particular state and its codes with the criminal codes of the rest of the United States. Beginning in Roper, the Court drew parallels between the state of the nation’s death penalty policies at the time of the Atkins decision, which famously ruled to narrow the usage of the death penalty by deeming the execution of the mentally disabled, unconstitutional. At the time of Roper only three years later, Justice Kennedy noted that, “30 States prohibit the juvenile death penalty, comprising 12 that have rejected the death penalty altogether and 18 that maintain it but, by express provision or judicial interpretation, exclude juveniles from its reach.”101 By drawing that parallel, Kennedy emphasized the weight that domestic shifts in criminal justice laws have for Supreme Court rulings as a matter of precedent. This is confirmed as Kennedy’s further argued that “the same consistency of direction of change has been demonstrated”102 and that the Court did “still consider the change..” from the last case to consider the death penalty for juveniles to this case “…to be significant.”103

In Justice Anthony Kennedy’s second majority opinion written for the Miller Trilogy in Graham v. Florida, additional emphasis is laid on the importance of considering nationwide domestic policy change, but in Graham this is in respect to sentences of life without parole for juveniles. As previously noted, the profile of state policy looked different in Graham than it did in Roper, with a majority of states permitting life without parole sentences for juveniles. In addition, federal law permitted the sentence for juveniles, as mentioned by Justice Kennedy in the majority opinion for Graham v. Florida.104 In fact, the Supreme Court found evidence of a national consensus against the sentence in this case to be “incomplete and unavailing.”105 However even in the Court’s rejection of the notion that such evidence existed in this case as strongly as it did in Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court’s majority still indicates the importance of using this kind of policy-based evidence in forming evolving standards of decency. To begin their opinion, the majority in the court quoted the Atkins opinion, stating, “The analysis begins with objective indicia of national consensus. ‘[T]he clearest and most reliable objective evidence of contemporary values is the legislation enacted by the country’s legislatures,’”106 outlining the role that state policy changes are intended to have in Supreme Court decisions determining the constitutionality of juvenile life sentences.

Authored by Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, the opinion in Miller v. Alabama, determining the unconstitutionality of mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles, also establishes a doctrinal necessity for the Supreme Court to factor state policy on JLWOP into the formation of evolving standards of decency. Justice Kagan recognizes and still rejects the State of Alabama’s argument that “because many States impose mandatory life-without-parole sentences on juveniles, we (The Court) may not hold the practice unconstitutional.”107 On the contrary, though 29 jurisdictions at the time allowed mandatory life without parole for juveniles processed and convicted as adults through court proceedings, she and the justices that comprised the majority in this case assert that the State’s case was weaker than the argument of national consensus that was rejected in Graham by Justice Kennedy. This weakness was due to the difference in nature that the consistent and unreduced use of JLWOP by the states for homicide crimes at the time of Miller compared to Roper and Graham, and for the way that Miller was not imposing categorical bans on a sentence.

A principal factor that Justice Kagan influences the Court’s decision for convicted juvenile defendant, Evan Miller is scientific evidence. Rather than focusing on national consensus to form evolving standards of decency, the Court’s reasoning was informed by evolving standards of decency and defining the proportionality of punishment for a juvenile. Though only one case set into precedent the application of international consensus, and two set into precedent the application of national consensus, all three Miller Trilogy cases indicate that scientific evidence regarding the status of the juvenile mind and its inherent differences from adults, should shape the ruling of a case.

Beginning with Roper, the Supreme Court weighed and incorporated evidence of youth’s poor impulse inhibition and rational decision-making skills with legal notions of reduced culpability. Based on the Supreme Court’s determination in Atkins v. Virginia that capital punishment must only be reserved for “a narrow category of the most serious crimes”108 in Roper, Justice Anthony Kennedy identified three reasons rooted in the biological differences between juveniles under the age of 18 and adults that “demonstrate that juvenile offenders cannot with reliability be classified among the worst offenders.”109 The three unique qualities of youth that Justice Kennedy names in the Roper opinion were, a “lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility;” a vulnerability and susceptibility for “negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure;” and finally, the character of juveniles is not fully formed and in fact “transitory.”110 Therefore, these qualities made the punishment of death for them cruel and unusual, when for adults it was and remains presently considered acceptable. However, the majority did not just blindly accept these factors based on the arguments posed by the attorney for Christopher Simmons. Instead, they relied upon various contemporary studies that revealed and corroborated this evidence. In fact, Kennedy quoted from accredited sources such as the peer reviewed, American Psychologist and renown psychologists such as Erik Erikson.111 In incorporating these sources into its decision to support their holding, the Supreme Court drew support from the science of adolescent psychology and its inherent effects on juvenile culpability. This research asserted: “Once the diminished culpability of juveniles is recognized, it is evident that the penological justifications for the death penalty apply to them with lesser force than to adults.”112

However, as was much later noted by Attorney Bryan Stevenson in his oral argument for Miller v. Alabama, these deficits exist in minors regardless of the crime. The Supreme Court would affirm this through their application of scientific evidence in Graham v. Florida years before to exclude non-homicide crimes from being subject to JLWOP sentences. Echoing the research deemed crucial to deciding the unconstitutionality of the death penalty for children, Justice Kennedy made repeated reference to those three unique qualities of juvenile offenders deemed constitutionally significant to narrow the forms of punishment a child could endure. As referenced above, they include a lack of maturity, vulnerability and susceptibility for detrimental influences and outside pressures, and the still unformed character of juveniles. 113 Building upon the precedent set in Roper, and the arguments offered by Terrence Graham’s attorneys, the majority opinion concluded: “No recent data provide reason to reconsider the Court’s observations in Roper about the nature of juveniles. As petitioner’s amici point out, developments in psychology and brain science continue to show fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds,” by applying these differences as a definitive matter of importance, fact, and compulsion crucial to answering constitutional questions about JLWOP.114 Once more, there is a clear pattern of scientific citation to support their ruling for Graham in this case. Secondarily, the science informed the justices when drawing the line of what they considered to be the only acceptable application of life without parole sentences for juveniles. Anthony Kennedy wrote, “to justify life without parole on the assumption that the juvenile offender forever will be a danger to society requires the sentencer to make a judgment that the juvenile is incorrigible. The characteristics of juveniles make that judgment questionable.”115 As will be discussed below, this holding, based upon the evolved standards of decency driven by science would be of great importance in Jones v. Mississippi.

Finally, in Miller v. Alabama those inherently unique qualities of youth that informed the holdings in Roper and Graham would prevail in an absence of state policy change acting as indicia towards evolving standards of decency. Though brief in her remarks, Justice Elena Kagan who wrote for the majority in this case concluded that mandatory life without parole sentencing schemes for youth were not only incompatible with the holdings of Graham and Roper, but they were also unjust given the role those deficits play in juvenile impulse inhibition and rational decision-making processes. Before rendering their decision on mandatory JLWOP sentences, the Court interpreted precedent and affirmed Attorney Bryan Stevenson’s arguments. Reflecting on Miller in the context of Graham, the Court says,

Graham insists that youth matters in determining the appropriateness of a lifetime of incarceration without the possibility of parole… And in other contexts as well, the characteristics of youth, and the way they weaken rationales for punishment, can render a life-without-parole sentence disproportionate.116

After arguing that the Graham decision made the death penalty and life without parole analogous sentences for juveniles due to their unique characteristics, Justice Kagan and the majority outlined the logic for their ruling within this framework. Because the death penalty requires individualized sentencing, and the Graham court concluded that JLWOP could be akin to the death penalty, the majority wrote, “Such mandatory penalties, by their nature, preclude a sentencer from taking account of an offender’s age and the wealth of characteristics and circumstances attendant to it.”117

In conjunction with Graham, Miller v. Alabama set into precedent numerous views on JLWOP and made mandatory several standards for review when sentencing juveniles. Firstly, the psychological differences in children make life sentences for them akin to capital punishment. Due to this, a juvenile life sentence penalty must be subject to the highest standards of review by lower court sentencing bodies. Moreover, as in Miller, the review must also be subject to the precedents set in death penalty Supreme Court cases.118 Secondly, not only does juvenile status matter in sentencing, but the Supreme Court in Graham and Miller stated that in many cases, youth status precludes the application of certain sentences for certain minors.119 In other words, the unique factors of youth are the most paramount factor for consideration when sentencing, and is enough to render a punishment disproportionate.120 For the Supreme Court, these factors make interpretation of the Eighth Amendment different for juveniles and adults. Thirdly, and most pertinent to Jones v. Mississippi the Supreme Court set the precedent that the punishment of life without parole for juveniles is only acceptable for the children found “permanently incorrigible” by the courts that hear their case.121 Moreover, the Court has even acknowledged that this concept of “permanent incorrigibility” is difficult to discern as a quality present in youth at all.122 All three cases, Roper, Graham, and Miller did not only set important legal precedents for hearing these juvenile-related Eighth Amendment cases, but also created procedural and ethical standards regarding the way that they decide them. Namely, these procedural and ethical standards taking into account changing societal standards in addition to modern scientific findings about the juvenile brain that culminate in a general standard of behavior imposing as many protections for youth in sentencing as possible.

Jones v. Mississippi (2021) and the Downfall of the Miller Trilogy

In Jones v. Mississippi, the Court rejected evolving scientific findings about the unique sentencing needs of juveniles that provided support for its rationale in the Miller Trilogy line of cases, which included Roper v, Simmons, Graham v. Florida, and Miller v. Alabama, as discussed above. The attorney for Brett Jones, who at fifteen years old stabbed his grandfather to death and was subject to JLWOP in Mississippi, called on the court to recognize the unique qualities of youth and the implications that they have on sentencing, and honor the holdings of these previous cases. Jones v. Mississippi, however, resulted in a very different outcome. The Supreme Court, just nine years after their landmark decision in Miller, ruled instead in favor of the state of Mississippi.

Between Miller v. Alabama and Jones v. Mississippi, the Court decided another case, Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016), that is important to understanding the arguments presented in Jones. At the time, the Supreme Court was comprised of the same justices seated at the bench in Miller, with Justices Sotomayor, Ginsburg, Kagan, Breyer, and Roberts joining Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote for their majority. Montgomery v. Louisiana established that Miller retroactively applied. Crucially, though, Montgomery stated that “Miller did bar life without parole . . . for all but the rarest of juvenile offenders, those whose crimes reflect permanent incorrigibility.”123 In this case, the majority’s rationale ensured that this severe punishment was given as rarely as possible for convicted youth. They reiterated this point several times throughout Montgomery. While emphasizing the matter of permanent incorrigibility, the Court also stated,

Louisiana suggests that Miller cannot have made a constitutional distinction between children whose crimes reflect transient immaturity and those whose crimes reflect irreparable corruption because Miller did not require trial courts to make a finding of fact regarding a child’s incorrigibility… That this finding is not required, however, speaks only to the degree of procedure Miller mandated in order to implement its substantive guarantee.124

This determination was considered to have opened the door for and even encouraged the implementation of this official fact finding of “permanent incorrigibility” in the states’ courts, or the constitutional challenge compelling one in Jones.125

Brett Jones’ attorney attempted to emphasize this point 2021, relying on the precedent set by Miller and calling on the types of arguments used by the litigators that came before him and the holdings in the Miller Trilogy and Montgomery. Although the argument focused on procedure, Attorney Shapiro drew upon both the scientific community’s conclusions on adolescent psychology, and the evolved standards founded upon them. He opened his argument by stating, “Settled law recognizes the scientific, legal, and moral truth that most children, even those who commit grievous crimes, are capable of redemption,”126 as a basis to advocate for that higher standard of review to their cases. Though the justices questioned him on whether this deviated from the original intention of the Eighth Amendment, the attorney for defendant Brett Jones argued that a mandated implicit or explicit finding by a sentencing judge of whether a given defendant fits within the “permanent incorrigibility” rule was the natural and practical edification of a rule already set into precedent in Miller and Montgomery.127 Despite the precedents established by the holdings of the Miller Trilogy, and however frequent that emphasis on a necessity for only the “permanently incorrigible” to be sentenced to JLWOP, the Court was not persuaded by these arguments.

The Supreme Court that heard the Miller Trilogy oral arguments was a very different court than the one that had heard the oral arguments in Jones v. Mississippi. The Court that decided the Miller Trilogy and Montgomery was nearly evenly split, with Kennedy as the median justice. The conservatives were John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Antonin Scalia while the liberal wing originally included John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and David Souter. After the retirements of Souter was replaced by Sotomayor and Stevens was replaced by Elena Kagan. By the time of Jones v. Mississippi, the Supreme Court had a strong conservative majority made up of six justices: Clarence Thomas, John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy ConeyBarrett. Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion denying the petitioner’s request in this case.