Summary

Effective October 1, 2021, the Juvenile Restoration Act permits people who have served at least 20 years of a sentence for a crime that occurred when they were under the age of 18 to file a motion for reduction of sentence. This report documents the progress that has been made implementing the Act and its successes over the first year.

More than 200 individuals are eligible for consideration under the JRA, with approximately 160 eligible individuals represented by OPD and its legal partners. To represent its clients, the OPD’s Decarceration Initiative has assembled a team of Assistant Public Defenders, law school clinics, and pro bono attorneys, who often work collaboratively with social workers, re-entry specialists, or other experts. Working with their clients, the multidisciplinary legal teams normally develop release plans connecting clients with community re-entry organizations that support their transition from incarceration to freedom.

The Juvenile Restoration Act is predicated on research showing that most people who commit serious crimes as children eventually mature, become rehabilitated, and can be safely released. The operative statute permits a court to reduce a person’s sentence only if it determines that the person would not pose a danger to public safety and that the interest of justice would be better served by a reduced sentence.

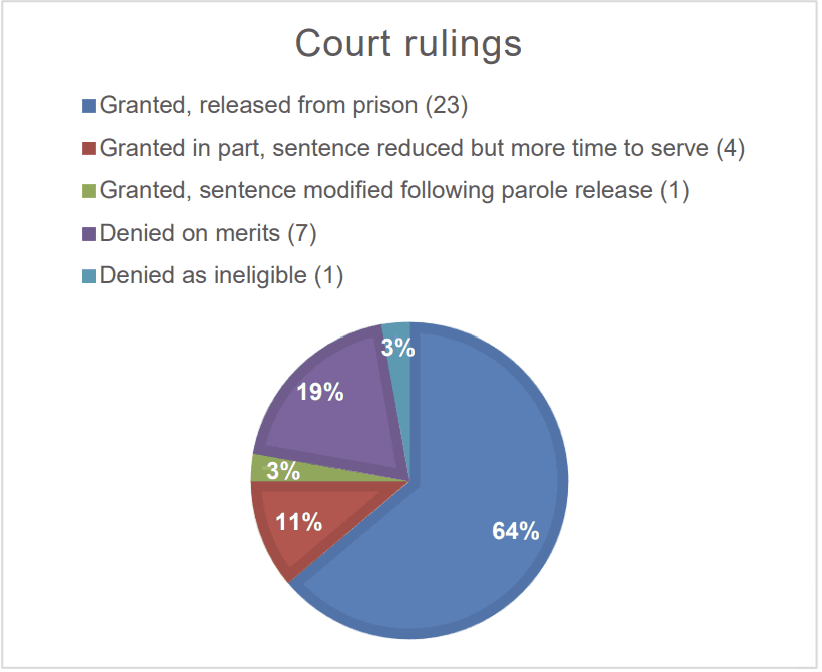

Consistent with what the research predicts and the legislature intended, courts in the first year since the Act took effect have reduced sentences and released people in the majority of cases decided. Courts have ruled on the motions filed by 36 people. They released 23 of those individuals from prison. In four more cases, courts granted the motion in part and reduced the duration of the sentence, but the individual has more time to serve before being released. In seven cases, the court reached the merits but denied the motion. In one case, the court denied the motion without a hearing because it found that the client was ineligible to file a motion – a decision that has been appealed. Finally, in one case, the individual was released on parole after the motion was filed but before the hearing; in that case, the court modified the sentence to place the individual on probation with conditions designed to maximize his chances of success.

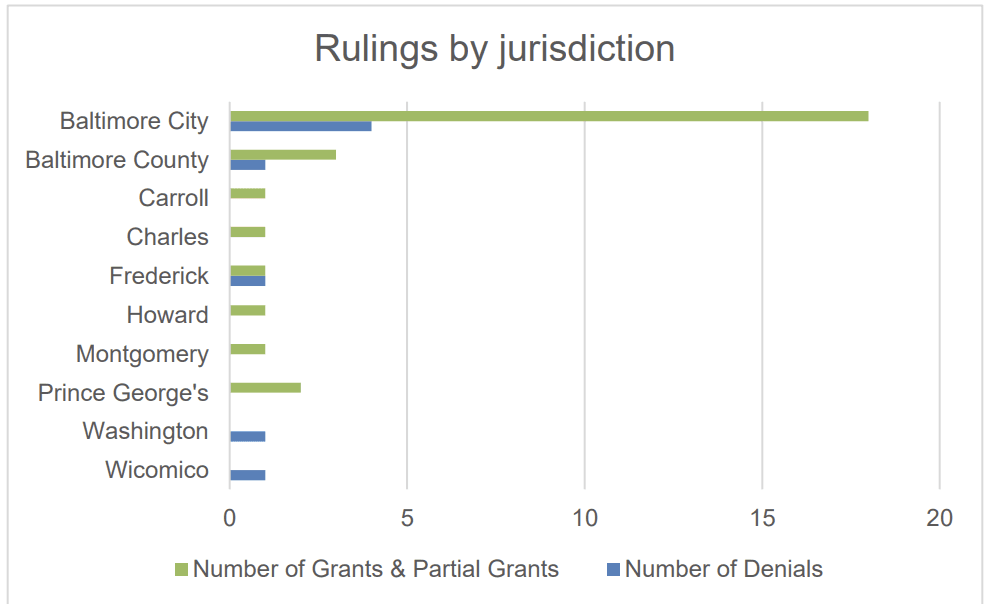

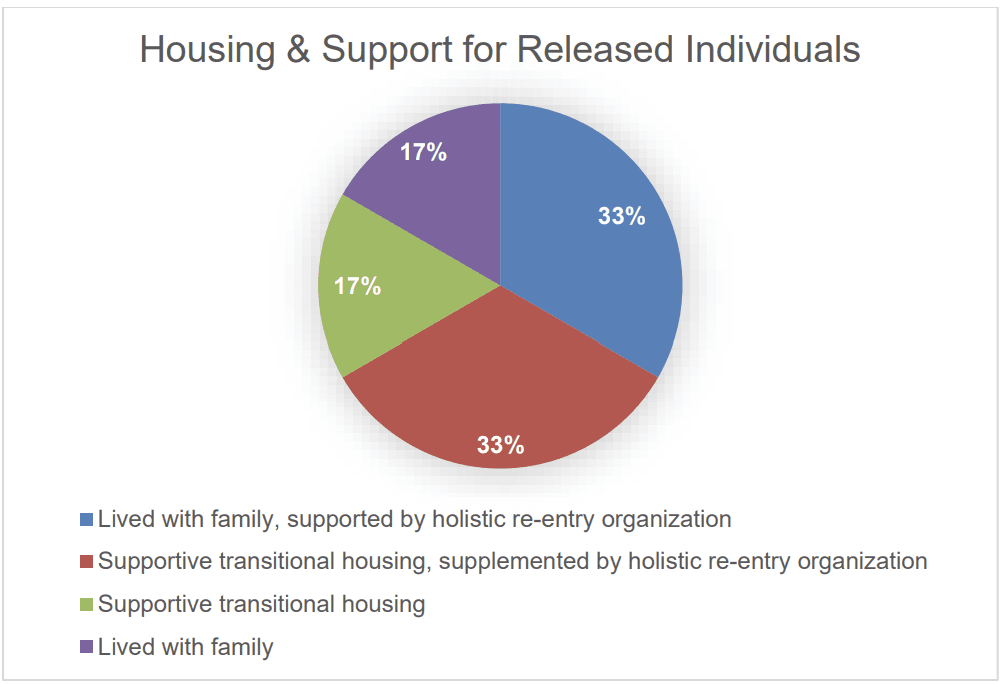

Almost two-thirds of the motions decided so far were in Baltimore City cases. The next three jurisdictions with the most rulings on these motions are Baltimore County (4 motions), Frederick County (2 motions), and Prince George’s County (2 motions), with six other jurisdictions having one ruling each. Most of the individuals who were released were connected with organizations that provide holistic re-entry services, some in conjunction with transitional housing. In the group released so far, half lived with family after their release, and the other half initially lived at a transitional housing program.

The first year of the Juvenile Restoration Act shows that, with an available court mechanism and robust re-entry planning and support services, many individuals who have served long sentences can be safely released. The General Assembly should expand on the success of the JRA by expanding eligibility for sentence reduction consideration to people who were emerging adults (18 to 25 year olds) at the time of the crime and older prisoners who have similarly served long prison terms. Funds should also be invested in implementing these recommendations and encouraging reliance on community based services where incarceration is no longer necessary for public safety.

What the Act did

The Juvenile Restoration Act of 2021 created two statutes that did three things.

Criminal Procedure Article § 6-235 addressed sentencing for children tried as adults by (1) prohibiting courts from imposing sentences of life without parole on juveniles tried as adults, making Maryland the 25th state to ban this punishment; and (2) providing that mandatory minimums no longer apply to children sentenced as adults.

Criminal Procedure Article § 8-110 allows a person who was convicted as an adult when they were a minor and who has served at least 20 years of a sentence imposed before October 1, 2021, to seek a sentence reduction. It provides that “[n]otwithstanding any other provision of law, after a hearing under subsection (b) of this section, the court may reduce the duration of a sentence imposed on an individual for an offense committed when the individual was a minor if the court determines that: (1) the individual is not a danger to the public; and (2) the interests of justice will be better served by a reduced sentence.”1 In making this determination, § 8-110 directs the court to consider the following factors:

(1) the individual’s age at the time of the offense;

(2) the nature of the offense and the history and characteristics of the individual;

(3) whether the individual has substantially complied with the rules of the institution in which the individual has been confined;

(4) whether the individual has completed an educational, vocational, or other program;

(5) whether the individual has demonstrated maturity, rehabilitation, and fitness to reenter society sufficient to justify a sentence reduction;

(6) any statement offered by a victim or a victim’s representative;

(7) any report of a physical, mental, or behavioral examination of the individual conducted by a health professional;

(8) the individual’s family and community circumstances at the time of the offense, including any history of trauma, abuse, or involvement in the child welfare system;

(9) the extent of the individual’s role in the offense and whether and to what extent an adult was involved in the offense;

(10) the diminished culpability of a juvenile as compared to an adult, including an inability to fully appreciate risks and consequences; and

(11) any other factor the court deems relevant.2

The statute requires the circuit court to hold a hearing on the motion where the individual and the State may present evidence, and the victim or a representative has the right to be heard. If the court denies the motion or grants it only in part, than the individual may file a second and third motion three years after the previous ruling.

The Purposes of the Act

The legislative history indicates that the General Assembly was motivated by the following information and concerns when passing the Act.

The diminished culpability of adolescents and their greater capacity for change

The judiciary has come to recognize that adolescents are less culpable for their criminal acts than adults and more capable of change as they age and mature. The Supreme Court has noted that “(1) juveniles lack maturity, leading to ‘an underdeveloped sense of responsibility,’ as well as ‘impetuous and ill-considered actions and decisions’; (2) juveniles are more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and peer pressure due, in part, to juveniles having less control over their environment or freedom ‘to extricate themselves from a criminogenic setting’; [and] (3) the personality of a juvenile is not as well formed as that of an adult, and their traits are more transitory and less fixed.” 3

As a result, the traditional justifications for punishment apply with less force to juvenile offenders. The case for retribution is not as strong because of the lesser culpability of children. Harsh sentences are unlikely to deter other juveniles because “the characteristics that make juveniles more likely to make bad decisions also make them less likely to consider the possibility of punishment, which is a prerequisite to a deterrent effect.”4 The need to incapacitate the wrongdoer to protect public safety diminishes and disappears as children mature and become rehabilitated. Finally, a “meaningful possibility of release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation” 5 incentivizes and thereby promotes rehabilitation.

The very low recidivism rate

Research has confirmed that most adolescents who commit serious crimes “age out” of criminal behavior and become law-abiding adults.6 This is particularly true of adolescents convicted of serious crimes, such as sex offenses and murder. “A meta-analysis of over thirty studies conducted over the past twenty years found that the recidivism rate for juvenile sex offenders is less than three percent” and that “among those juvenile offenders who did reoffend, the vast majority did so within three years of their first offense.” 7 Likewise, a recent study from Philadelphia found that among 174 people released after being sentenced to life without parole for murder committed when they were under 18 years old, only six (3.5%) were re-arrested, with only two of these cases (1%) resulting in a new conviction. 8

The need to redress severe racial disparities

In the Juvenile Restoration Act’s Racial and Equity Impact Note, the Maryland Department of Legislative Services (DLS) acknowledged the appalling racial disparities in which children get charged as adults and which children receive more severe sentences.

Citing data from 2019 (the most recent pre-pandemic year), DLS noted that “African American youth, or 10- to 17-year-old children identified as Black, are more than seven times as likely to be criminally charged as adults than their White peers in the State.”9 Although Black children comprised only 32% of Marylanders ages 10 to 17, they comprised 81% of children charged as adults.10 Additionally, approximately 80% of people serving 10 years or more in Maryland prisons are Black.11 “Given existing data and scholarly research,” the Racial and Equity Impact Note informed the General Assembly, “the [Juvenile Restoration Act] has the potential to reduce the inequitable impacts on Black youth criminally charged as adults in the State.”12

The science of adolescent development

The judiciary’s recognition of the lesser culpability of adolescents is rooted in science. Adolescents are immature both in their emotional development and in the physiology of their brains. This makes them less mindful of the potential consequences of their actions, less able to effectively regulate strong emotions, more impulsive, more likely to take risks, and more susceptible to negative influences from peers and adults.

Preparing for Implementation

Shortly after the passage of the Juvenile Restoration Act, the Maryland Office of the Public Defender (OPD) established the Decarceration Initiative to coordinate representation of indigent people eligible to file a motion for reduction of sentence under the Act, and to advocate for the adoption of similar “look back” provisions authorizing the reduction of sentences for other individuals who have served lengthy periods of incarceration.

The OPD’s Decarceration Initiative partnered with the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, the Family Support Network, former Baltimore City State’s Attorney Gregg Bernstein, and other organizations and advocates to prepare to represent eligible individuals on motions for reduction of sentence. This leadership group guided much of the initial work.

With help from the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, the OPD began the process of identifying eligible individuals and informing them of the new law and its potential relevance to their sentence. As of September 2022, approximately 160 eligible indigent individuals have received representation through the OPD.

The Act took effect at a challenging time for the OPD. In addition to its high caseloads, the pandemic had created a backlog of cases awaiting jury trials. To increase its bandwidth, the OPD and its aforementioned partners recruited dozens of pro bono attorneys and teamed up with law school professors and clinics from the University of Baltimore School of Law, the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, and the American University Washington College of Law to provide representation to eligible individuals.

Next, the OPD developed and presented training curricula and resources for legal teams (attorneys, social workers, paralegals, core staff, and others) working on these cases, and conducted bi-weekly drop-in meetings on Zoom. Finally, in July 2021, the OPD began assigning legal teams to represent individual clients.

Preparing the Motion for Sentence Reduction

The first step for an eligible individual to be considered for a sentence reduction is to file a motion in circuit court, typically to be decided by the sentencing judge if they are still on the bench. The motion typically addresses the legal background of the JRA, the factual circumstances unique to that client, the factors the court is required to consider under CP 8-110, and the proposed release plan.

To prepare the motion, a legal team typically meets with their client multiple times, gathers information from the court, prison and parole files, and contacts family members or close friends of the client. In some cases, the team may retain a psychologist to conduct a psychological evaluation or risk assessment of the client.

As part of preparing the motion, the legal team and the client typically develop a proposed release plan for meeting the client’s needs if they are released. OPD’s forensic social workers and reentry specialists have played a vital role in identifying client needs and connecting them with relevant services. Although not required by the Juvenile Restoration Act, these plans are an important part of helping the client to be successful on the outside and they build upon proven practices established with the “Unger defendants.”

Planning for Re-entry

People who were incarcerated as children and have been locked up for decades sometimes lack the life skills needed for independent living. They may have never lived on their own, paid rent, had a bank account, cooked food for themselves, or gotten a driver’s license. They also may not have the identification documents they need, like a birth certificate or a Social Security card, in order to receive income or services.

The world has also changed while they were imprisoned in unanticipated ways, large and small. Advances in technology are particularly challenging. Most job applications are done online, as are many other transactions. Smartphones are ubiquitous and used as phones, to text, as cameras, as wallets. Many stores have self-checkouts, which can cause a lot of anxiety among clients unaccustomed to them and terrified of being accused of shoplifting.

People incarcerated long-term often face chronic health conditions that create additional challenges, including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, liver disease and cancer. They need to sign up for medical insurance, access primary care, and obtain prescriptions or medical supplies in the community. Many have to learn self-management skills for conditions like diabetes after relying on care from correctional medical providers in the Chronic Care Clinic. It is important to ensure continuity of any ongoing medical care, from daily medication to dialysis or even nursing care.

Pre-release re-entry planning

Re-entry planning is crucial for both the success of the motion and the success of the client. It requires assessing the needs of the client, identifying resources to meet those needs, and developing a release plan that can guide the client’s transition home and provide sufficient services and support.

For OPD clients, the legal team often includes a social worker from OPD’s Social Work Division or a re-entry specialist from its Community Engagement Reentry Project, who provide their expertise in release planning and experience assisting clients who have served lengthy prison sentences.

The Social Work Division’s licensed clinicians conduct comprehensive biopsychosocial assessments and utilize validated screening and assessment tools to determine a diagnosis (or diagnoses) for individuals with mental health and/or substance use disorders. In addition to identifying appropriate treatment for inclusion in the release plan, these assessments provide valuable background information for the motion and, where appropriate, the social worker may serve as a witness at the hearing.

Community Engagement Reentry Project staff utilizes its knowledge and connections with community service providers to ensure that clients are connected with the full range of services that they need. This may include treatment services, employment and workforce development, life skills training, GED and college planning, vital documents retrieval, housing, food security, clothing, technology training, transportation, and peer support.

DPSCS’s Social Work and Case Management Units have helped with this process by ordering birth certificates for prisoners who may be eligible for a sentence modification, conducting initial release planning with them, and working with OPD social workers on cases where the client has special needs. Many DOC Social Workers have known these same individuals for years through their participation in groups and workshops. When a court date and potential release date is scheduled DOC Social Workers can provide pre-release services to prepare individuals for release.

Connecting clients with community-based services and support

The release plans developed rely on the expertise, resources, and dedication of organizations within the community that have committed to assisting individuals returning home from prison. These include:

Re-entry service providers such as No Struggle No Success in Baltimore, The Bridge Center at Adam’s House in Prince George’s County’s, and Anne Arundel County Police Department's ReEntry & Community Collaboration Office.

Supportive transitional housing programs, such as T.I.M.E. Organization (“Teaching, Inspiring, Mentoring & Empowering the Minds of Tomorrow’s Leaders.”) in Baltimore, High Hopes also in Baltimore, The Way Homes in Anne Arundel County, and the Damascus House RISTORe Program (Rehabilitating Individuals So They Overcome Recidivism) in Prince George’s County.

Peer support and mentorship in meetings held by the Living Classrooms’ First Monday Empowerment Group and H.O.P.E. (Helping Oppressed People Excel), where members provide emotional and practical support for each other as they navigate the challenges of adjusting to life outside prison.

The Hearing

The Juvenile Restoration Act requires that the court hold a hearing on a motion for sentence reduction. After a motion is filed, courts have generally been scheduling hearings around two to six months later. In the wake of the pandemic, these hearings are sometimes done in person, sometimes via videoconference technology, and sometime through a hybrid of the two. At that hearing, the individual who filed the motion and the state are permitted to present evidence, and the victim or a victim’s representative has the right to notice and an opportunity to present a statement.

The movant's presentation

Counsel for the person filing the motion (i.e., the movant) usually begins with an opening statement summarizing the reasons to grant the motion and addressing any matters that may be of special concern to the judge. Counsel then normally calls witnesses, often to speak about the defendant’s character and growth and/or the release plan, and presents other documents and information that may be relevant. After the state’s presentation and any statement by a victim or victim’s representative, counsel for the movant normally responds to points they’ve raised. Additionally, the person seeking a sentence reduction has an opportunity to address the court in allocution at the end of the hearing.

The state's presentation

The state’s approach to these motions differs depending on the jurisdiction. The State’s Attorney’s Offices (SAOs) in Baltimore City and Prince George’s County, which together have the majority of these cases, have established units to review requests for sentence reduction on a case-by-case basis, supported such requests where they believe it is in the interest of justice to do so, and opposed motions where they belief release is not presently warranted. They often take an active role in recommending that certain community re-entry organizations be made a part of the release plan. Elsewhere, SAOs routinely oppose these motions for sentence reduction.

Statement by the victim or a victim's representative

SAOs make efforts to contact the victim or a family member to notify them of the hearing and ascertain their position on the request for sentence reduction regardless of whether they’ve formally requested notification of such hearings. A victim or victim’s family member is never required to attend the hearing. In cases where the SAO has reached a victim or victim’s representative, some opt not to participate at all, others don’t attend but ask the Assistant State’s Attorney to relay a written or oral statement to the judge, and still others attend the hearing. When a victim or a victim’s family members present their position to the court, these positions have varied widely. Some staunchly oppose any relief. Others speak about the impact of the crime but defer to the court as to the request for sentence reduction. Still others, having learned of the person’s remorse and rehabilitation, support release and use the hearing as an opportunity to convey to the person forgiveness and hope that they will lead a good life in the future.

Results and Trends

Statewide results

In the first year of the Juvenile Restoration Act, courts have decided 36 motions.13 In 23 of these cases – almost two-thirds – the courts granted the motion and released the defendant from prison. In four more cases, courts have granted the motion in part and reduced the duration of the sentence, but the individual has more time to serve before being released. In seven cases, the court reached the merits but denied the motion. In one case, the court denied the motion without a hearing because it found that the client was ineligible to file a motion; an appeal is pending. Finally, in one case, the individual was released on parole after the motion was filed but before the hearing; in that case, the court modified the sentence to place the individual on probation with conditions designed to maximize his chances of success.

Results by jurisdiction

Baltimore City has both the most JRA eligible cases and the most motions decided (22). More than eighty percent (80%) of those rulings granted the motion in whole or in part. The next three jurisdictions with the most rulings on these motions are Baltimore County (4 motions), Frederick County (2 motions) and Prince George’s County (2 motions), with six other jurisdictions having one ruling each. Aside from Baltimore City, the numbers of rulings in these jurisdictions is too small to suggest a trend or pattern.

Initial housing and support for released individuals

Twenty-four (24) of the individuals granted sentence reductions have been released: twenty-three (23) as a direct result of the sentence modification, and one (1) who was released on parole and subsequently had his sentence modified by the court. Twelve (12) of these individuals lived with family; twelve (12) went to a transitional housing program. Twenty (20) of the released individuals (approximately 83% of those released) received holistic re-entry support through a transitional housing program, a re-entry organization, or both.

Recidivism

At the end of the first year of the Juvenile Restoration Act, none of the 24 individuals who were released have been charged with a new crime or found to have violated probation. 14

Success Stories

What follows are short interviews with some of the people who have been released as a result of the Juvenile Restoration Act. To protect their privacy and that of their families, we are not using their full names, and are using photographs run through a filter. Interviews have been lightly edited for brevity. It is worth mentioning that nearly all of those we interviewed knew others who remained incarcerated and deserved a chance at life outside of prison but did not meet the specific JRA eligibility criteria. They hoped that those individuals would one day get that opportunity as well.

K.M.

K.M. was sentenced to life plus 30 years in prison for a crime he committed when he was seventeen. He was incarcerated for more than 37 years. In the years preceding his release, correctional officers commended him for helping to resolve conflicts and prevent violence in the prisons where he was incarcerated. In early 2022, he was released at the age of 55 pursuant to the Juvenile Restoration Act. Because he had struggled with addiction in the past, he went from prison to TIME Organization’s transitional housing program. After graduating from the program, he now lives with his sister.

What are you doing now?

I’m working at a PRP, a psychological rehabilitation program, as a field agent, going into the community and finding people who need help. I’m also working part-time for the Mayor’s Office going into hot spots and encourage people who are using drugs or are homeless to accept resources we have to help them get off the streets.

What were you looking forward to most when you were released?

Being with my family, and trying to establish and rebuild relationships with my daughter, and grandbabies. That’s the most important thing, rebuilding these relationships with family members, the ones who are still alive.

What advice would you have for others acclimating to life after release?

Patience. You’ve got to have patience. Everything is not going to go the way you want it to go. I’m fortunate to have a lot of family support and friend support, but some guys don’t. I had TIME to help me, and I’m trying to put myself in a position where I can help other people when they come out.

What was the best thing about coming home?

Probably my sister. We fought so hard for me to get out, and when it happened, I saw the relief on her face. And since I’ve been home, we’ve had the best time.

What do you hope to be doing in five years?

I want to have my own PRP. I want to get my AA degree and become an addictions counselor. My main focus would be guys who are in prison, because there’s a big drug problem in prison.

What would you like legislators to know?

There are a lot of brothers in there who deserve a second chance. There’s a lot of crime in the streets now, but I guarantee that if some people got a second chance, they’d help turn that around.

W.H.

W.H. was sentenced to life plus 30 years in prison for a crime that occurred when he was sixteen. After serving more than 30 years, he was released in the late spring of 2022 at the age of 47.

What are you doing now?

I’m living in a transitional home right now. I’m also doing some prisoner advocacy work for an organization called Life After Release in Prince George’s County.

What were you looking forward to most when you were released?

To be honest, not knowing if this would be a reality, I couldn’t think in terms of “I want to do this, I want to do that.” I just wanted to be free, to be with my family, to have options after being in a place where we didn’t have options.

What’s been challenging?

Learning how to shop. When I got home, Mr. Mitchell from NSNS took me to Walmart, and seeing all these people and all this stuff was overwhelming. So he took me and walked me through each aisle and showed me what was there, and broke down how to look through clothes and find ones that would work. In prison, we got issued clothes and didn’t really have options.

Registering for Medicaid and getting my health insurance together, getting acclimated to a computer and using passcodes. I tell people, if you don’t know, please ask questions. I tell my family and friends, don’t assume that I know something, walk me through the steps. Even crossing the street – learning to use crosswalks again. You have the mindset “I don’t want to break any laws” and so I’m extremely careful.

What do you hope to be doing in five years?

My wife lives in Georgia. We want to open up a re-entry program and transitional home there for people leaving prison.

What would you like legislators to know?

That a child is a child, regardless of the crime that he’s committed. And I’m not saying people shouldn’t be held accountable for the crimes they’ve committed. But I think one of the worst things they can do is put a child in an adult facility. It doesn't rehabilitate them. I was fortunate that some older people in prison encouraged me and helped me, but most people don't have that experience.

J.B.

J.B. was sentenced to life in prison when he was seventeen years old. He was released pursuant to the Juvenile Restoration Act after serving more than 26 years. About two weeks after he was released, he started working as a facility maintenance technician for a vehicle rental company.

What are you doing now?

I’m currently living in a transitional home owned by the Damascus House Foundation. I was recently moved to a lower-level home that provides me with more freedom, but still gives me structure and support. I am also working over 50 hours per week as a facility maintenance technician.

What were you looking forward to most when you were released?

Being able to walk out the front door and have the freedoms I did not have on the inside, like the ability to reconnect with family, go to the fridge, take walks, and walk in the grass. There is not one thing you look forward to more because everything is precious.

What advice would you have for others acclimating to life after release?

Don’t try too hard. If you let it happen, it will happen. Also, your worst day on the outside is ten times better than any day on the inside. When you’re in as long as I was, you learn to be appreciative of everything. Some people say I am doing too much with working over 50 hours per week, but I am just trying to do what needs to be done to have a good life.

What was the best thing about coming home? Being able to connect with people who matter to me. I am able to see these people at dinner rather than in a visiting room.

What do you hope to be doing in five years?

I hope to be off probation and truly be clear. I really enjoy my current job. I like being able to work directly with people and complete a variety of different tasks throughout my day. There is room for advancement in my current job, so I hope to stay here.

What would you like legislators to know?

There is a ton of value in the people serving life sentences. These individuals can provide value to the workforce and can help stabilize the community. We don’t want to see today’s youth go through what we went through. It is helpful to have someone in these communities telling youth directly their experiences, so they do not make the same mistakes.

G.G.

G.G. was sentenced to life suspended all but 50 years in prison for a crime he committed when he was sixteen. He was incarcerated for more than 28 years. In early 2022, he was released at the age of 44 pursuant to the Juvenile Restoration Act. He went from prison to living with his wife.

What are you doing now? I’m currently in barber school. I am also investing in real estate. When I am not in school or investing, I attend community events where I cut hair for students and the homeless, and I provide people with physical training.

What were you looking forward to most when you were released? There isn’t one particular thing you look forward to doing the most; you want to do everything.

What advice would you have for others acclimating to life after release? I would prepare for release beforehand. When doing my boxing training, I don’t give advice before they get into the ring; I train them. Therefore, I am not going to give you advice before you get into the ring of life. You must train before you are released to understand how this world has changed.

What was the best thing about coming home?

I’m not in prison; I’m free! I get to spend time with my wife. I now have the ability to grab my desires and can take my life into my own hands. I have the opportunity to prove those who doubted me wrong and prove I am anew.

What do you hope to be doing in five years? I hope to be financially free. I also hope to help the community and those who are still incarcerated. I want to travel, stay healthy, eat good food, and create stronger relationships.

What would you like legislators to know? Give those that are deserving a second opportunity. If they prove they are deserving, they should be provided a second chance.

J.P.

J.P. was sentenced to life in prison for a crime he committed when he was seventeen. He was incarcerated for more than 38 years. In early 2022, he was released at the age of 56 pursuant to the Juvenile Restoration Act. He went from prison to living with his wife.

What are you doing now?

I’m currently working as a tailor. I have lived with my wife in our own place since I was released.

What were you looking forward to most when you were released? When I found out I was going to be released I almost jumped out of my skin. I was very grateful and thankful to have a second chance at life. It was a breathtaking experience and a tremendous blessing.

What advice would you have for others acclimating to life after release? I would tell them to just breathe and take your time. I would also tell them to take it all in one moment and event at a time.

What was the best thing about coming home?

Being able to spend quality time with my wife and family. I also enjoyed being able to eat great food.

What do you hope to be doing in five years?

I hope to be off probation and to fully regain my citizenship as a free person. With respect to my career, I hope to be a peer recovering specialist who helps those with alcohol and drug issues. I want to promote the overall well being of these individuals.

What would you like legislators to know?

This legislation allows for people to have a second chance at life. It allows them to give back to communities and to share their life experiences with others. If we are able to turn one life around, it makes it all worth it.

Next steps

The first year of the Juvenile Restoration Act shows that, with an available mechanism, courts are able and willing to identify individuals who have been rehabilitated after serving a long period of incarceration and can be safely released. Robust re-entry planning and support services both support court decisions to reduce the terms of incarceration and promote successful transition back to the community. OPD recommends the following common sense measures to further reduce unnecessary incarceration and encourage successful returns home.

Allow other rehabilitated individuals to seek sentence reduction

Emerging adults (18 to 25 year olds):

There is broad agreement that the age at which brain development is “complete” is approximately 25 years old.15 The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has recognized that “although adolescents may develop some adult-like cognitive abilities by late adolescence (roughly age 16), the cognitive control capacities needed for inhibiting risk-taking behaviors continue to develop through young adulthood (age 25).”16 “The neuroscientific evidence,” their report explains, “bolsters the argument that adolescents—including young adults in their 20s—are neurologically less mature than adults,” which “adds strength to the understanding that adolescent wrongdoing is unlikely to reflect irreparable depravity.”17 The report notes that “[w]hile older adolescents (or young adults) differ greatly in their social roles and tasks from younger adolescents, it would be developmentally arbitrary in developmental terms to draw a cut-off line at age 18.”18 And yet, this is what the Juvenile Restoration Act currently does. To better align the law with the science, the General Assembly should pass legislation to give rehabilitated people who committed crimes when they were emerging adults – neurologically, still adolescents – a similar opportunity to file a motion for reduction of sentence after they’ve been incarcerated for a substantial period of time.

Older prisoners:

There are approximately 630 people in Maryland prisons who are 60 years of age or older and have served at least 15 years.19 Most of these individuals can be safely released. The Justice Policy Institute has observed that “[o]lder prisoners pose a low public safety risk due to their age, general physical deterioration, and low propensity for recidivism.”20 Releasing older rehabilitated prisoners would save the state the high costs associated with caring for prisoners as their health deteriorates from a combination of age and the harsh conditions of imprisonment.21 It is also the humane thing to do. No one should spend the last weeks, months or years of their life in the bleak environs of a prison hospital ward unless absolutely necessary to protect the public, and it almost never is necessary. We should be better than this. The General Assembly should enact legislation to allow older prisoners who have served a substantial period of time to file motions seeking their release from incarceration.

Increase funding for organizations that implement these statutes

Releasing non-dangerous prisoners is much less expensive than keeping them incarcerated. The money saved can be invested in ways that promote public safety. Financially, this is a no-brainer. That said, it is important for the state to invest the resources necessary to implement such reforms effectively. Litigating motions for reduction of sentence, including release planning, requires lawyers, social workers, re-entry specialists, funds for experts, and appropriate support staff. A successful transition from prison to life in the community requires adequately funded re-entry organizations and, for some individuals, supportive transitional housing. Investing in these services today will save the state millions of dollars it would otherwise waste keeping non-dangerous people imprisoned.