Abstract

Background: Opioid use disorder is one of the most severe forms of substance use disorder and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Opiate overdose deaths in the US are increasing every year, claiming over 100,000 lives in 2022. Psychological trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder are major health problems in the United States and may contribute to the development of an opiate use disorder. The purpose of this study was to examine the association of psychological trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder with opiate use disorder. Methods: This study used a retrospective design with a convenience sample size of n = 150 participants diagnosed with opiate use disorder or substance use disorder from a drug treatment center in urban Pennsylvania. Retrospective data was collected on demographic characteristics, trauma exposures, diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder, opiate use disorder, and substance use disorder. Demographic data was gathered using a demographic survey, psychological trauma exposure was documented using the self-reported Life Events Checklist, and a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, opiate use disorder, and substance use disorder was confirmed as documented in the medical record by mental health providers. Results: Persons with psychological trauma exposure >5 are more likely to develop opiate use disorder, Chi-Square (χ2 = 5.17, df = 1, p = 0.023). Conclusion: Our study showed that psychological trauma exposure may lead to opiate use disorder, emphasizing the importance of identification of psychological trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis as part of trauma-informed strategies during the treatment of persons with opiate use disorder to help prevent disability and death.

Introduction

Opiate use disorder (OUD) is defined as a pattern of opioid use leading to problems or distress that may result in physical and psychological dependence attributed to complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, environment, and life experiences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), 2020). Risk factors for opiate use disorder include adverse childhood experiences (ACES), psychological trauma exposure, younger age of first use, co-occurring mental health disorders, and diminished availability of recovery resources and mental health services (ASAM, 2020). Recreational opiate use and OUD may result in increased morbidity and mortality. Opiate overdose deaths in the US are increasing every year, claiming over 100,000 lives in 2022 (American Medical Association, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (CDC), 2020; National Institutes of Health, 2023). OUD is a subcategory of substance use disorder (SUD). SUD is a complex brain disease characterized by the uncontrolled use of a substance despite harmful consequences. Examples of types of substances include opiates, cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana, alcohol, etc. (APA, 2013).

Trauma exposures are a common occurrence. The results of a worldwide survey study by Benjet et al. (2015) reported that over 70 % of respondents reported a traumatic event, and 30.5 % of respondents were exposed to four or more PTEs in their lifetime. A trauma exposure is defined as an encounter with a negative event that may lead to an emotional response that overwhelms a person's mental capacity to process and integrate the event such as violence, sexual assault, a terrorist attack, or a natural disaster. Trauma exposure can lead to a trauma -or- stressor-related disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The DSM-5 criteria for PTSD include direct or indirect exposure to a traumatic event, followed by a total of eight symptoms in four categories including, intrusion, avoidance, negative changes in thoughts and mood, and changes in arousal and reactivity (APA, 2013). However, people's lives can be negatively impacted by symptoms that don’t meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder. For example, experiencing psychological trauma exposures can manifest with symptoms that don’t meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder, but these symptoms can cause significant impairment in function and health depending on the number of trauma exposures. Trauma exposures may consist of psychological trauma exposure (PTE), trauma and stress-related disorders including PTSD, and adverse childhood experiences (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2022). This study will focus on PTE and PTSD. Persons with a history of PTEs, PTSD, and comorbid SUD may experience a more complicated and costly course of treatment including chronic physical and mental health problems, poorer social functioning, higher rates of suicide attempts, increased risk of violence, as well as poor treatment adherence and outcomes (Watkins et al., 2022). Based on these findings, some studies support integrated trauma treatment for veterans with co-occurring PTE, PTSD, and SUD (Blakey et al., 2022).

While the relationship between PTE, PTSD, and SUD is well documented (Brady et al., 2021, p. 123)., these factors are understudied concerning OUD (Bernardy & Montaño, 2019). Several studies have reported that 52 % of persons diagnosed with OUD also screened positive for comorbid PTSD (Hassan et al., 2017; Hooker et al., 2020; Shiner et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2016). Other studies have reported that veterans with concurrent PTSD treatment remained in OUD treatment longer (Meshberg-Cohen et al., 2019; Mills et al., 2018).

While some studies have shown a high rate of PTSD among SUD clients, none have specifically studied the influence of PTE on OUD. Bernardy and Montaño (2019) notes that difficulties in determining the rate of PTE among OUD clients result from OUD diagnosis being grouped with SUD diagnosis. This has limited our knowledge of the extent of PTE among persons suffering from OUD. Understanding the influence of PTE on OUD is crucial for the formulation of targeted interventions that support the prevention, treatment, and recovery of PTE and OUD. The purpose of this descriptive study is to examine the influence of PTE on the development of OUD in an urban treatment facility in Pennsylvania and to provide foundational work for future interventional studies involving PTEs and OUD.

Aim 1: Describe the demographic characteristics of OUD and SUD participants.

Aim 2: Examine the associations between PTE and PTSD diagnoses of OUD and SUD participants.

Aim 3: Examine the number PTE of occurrences in OUD and SUD participants.

Theoretical framework

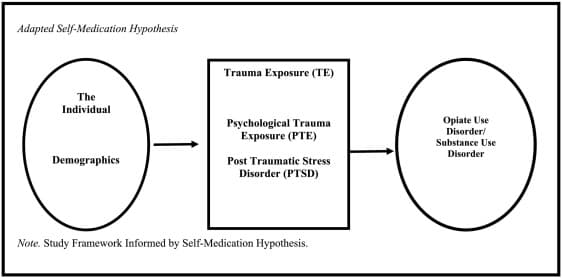

The “self-medication hypothesis” (SMH) of substance use disorder states that persons may self-medicate with substances to attempt to manage emotional dysregulation and/or distressful emotional symptoms (Khantzian, 1997). The purpose of the “self-medication hypothesis” (SMH) is to explain the relationship between distressing emotional states and the development of SUD. The theory structure is linear and is consistent with a health model. The overall assumption about the theory is that substances are consumed selectively, based on their pharmacological effects to lessen emotional reactivity or distress. Another assumption of the theory is the disease model of addiction. The “SMH” uses concepts of person, distressing symptoms with maladaptive coping, and substance use disorder.

These concepts are similar to those of interest to professionals caring for clients in recovery from SUD. Although not explicitly stated, it can be inferred that the concept was defined as a human comprised of biological, psychological, and social factors since the “SMH” was formulated by a psychiatrist in 1997. Distressing symptoms are defined as affective symptoms of anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation. Maladaptive coping is defined as, “characteristic patterns of defense and avoidance that both reveal and disguise the intensity of their suffering, their confusion about their feelings, or how they are cut off from their feelings” (Khantzian, 1997). SUD is defined as the compelling, progressive, and deteriorating use of addictive substances that can lead to a loss of function, relationships, and life (Khantzian, 1997) (Fig. 1). The “SMH” describes one possible relationship between distressing symptoms and SUD, however, other clinically relevant circumstances were missing. For example, the “SMH” attributed distressing symptoms to mental health conditions, such as diagnosis of PTSD, depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia. However, people’s lives can be negatively impacted by symptoms that don’t meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder.

The adapted SMH framework’s concepts comprise the individual, TE, and OUD/SUD. The individual concept includes demographics and TE concepts consist of PTE and PTSD. The maladaptive coping concept includes OUD/SUD (Fig. 2).

Materials and methods

The study employed a chart review of participants from the outpatient substance use facility at the drug and alcohol division of Crozer Chester Medical Center (CCMC) in the city of Chester, Pennsylvania. An exempt IRB approval from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) and CCMC was obtained.

A convenience sample size of n = 150, comprised of 75 OUD clients and 75 SUD clients was used to collect data from the medical records of the most recently admitted clients. The sample size was met by counting backward until the target sample size was met starting from April 2022. All identifiable information was removed or redacted. The investigator manually reviewed subjects' medical records for inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as, collected data for variables of interest over two weeks, and stored an encrypted and locked file.

An investigator-developed demographic survey was used to collect demographic data and “The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) was used to measure PTE. The demographic tool assesses gender, age, as well as race, and ethnicity. The LEC-5 is a self-report screening tool that measures potentially traumatic events in a respondent's lifetime. The LEC-5 assesses exposure to sixteen events known to potentially result in emotional distress or PTSD. The LEC-5 includes one additional item assessing any other extraordinarily stressful event not captured in the first sixteen items” (Weathers et al., 2013).

The LEC-5 does not have a recognized scoring method. However, the respondents designate levels of exposure to each type of possible traumatic event included on a 6 categorical scale. The categories are “happened to me”, “witnessed it”, “learned about it”, “part of my job”, “not sure “ or “doesn't apply” The categories of “happened to me” and/or “witnessed it” will be counted as PTE if selected. PTE occurrences will be counted as 1–17, as the number of items detailed on the LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013). Psychometrics are not currently available for the LEC-5 (Gray et al., 2004).

Results

Demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. In a sample size of n = 75 OUD, the clients' ages ranged from 18 to 63 with an average participant age of M = 37.12 (SD = 10.52), 51 % were female, 49 % were male, 21 % were African American/Black, 73 % were White, Non-Hispanic, and 5 % were Hispanic/Latino. In the SUD group (n = 75), the clients' ages ranged from 18 to 73, with an average participant age of M = 46.64 (SD = 14.14). In this group, 41 % were female, 58 % were male, 55 % were African American/Black, 43 % were White, Non-Hispanic, 1 % were Hispanic/Latino, and 1 % were Asian.

Psychological traumatic experiences

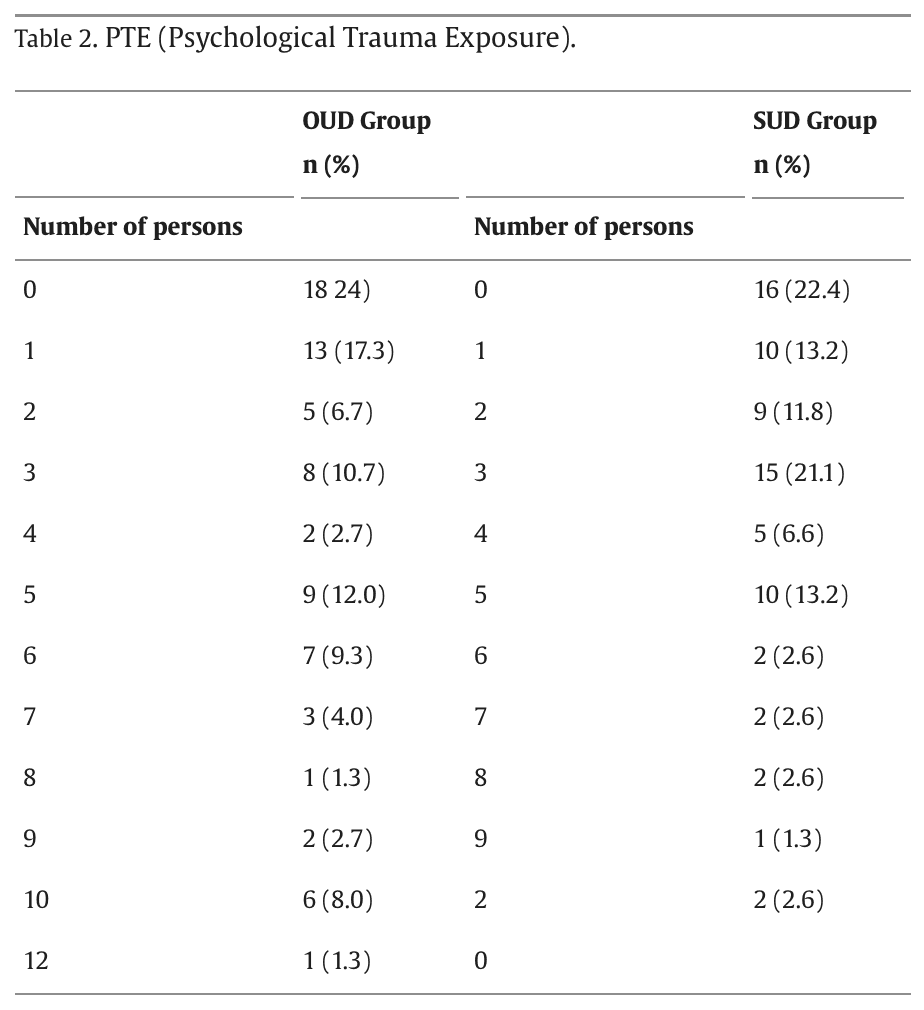

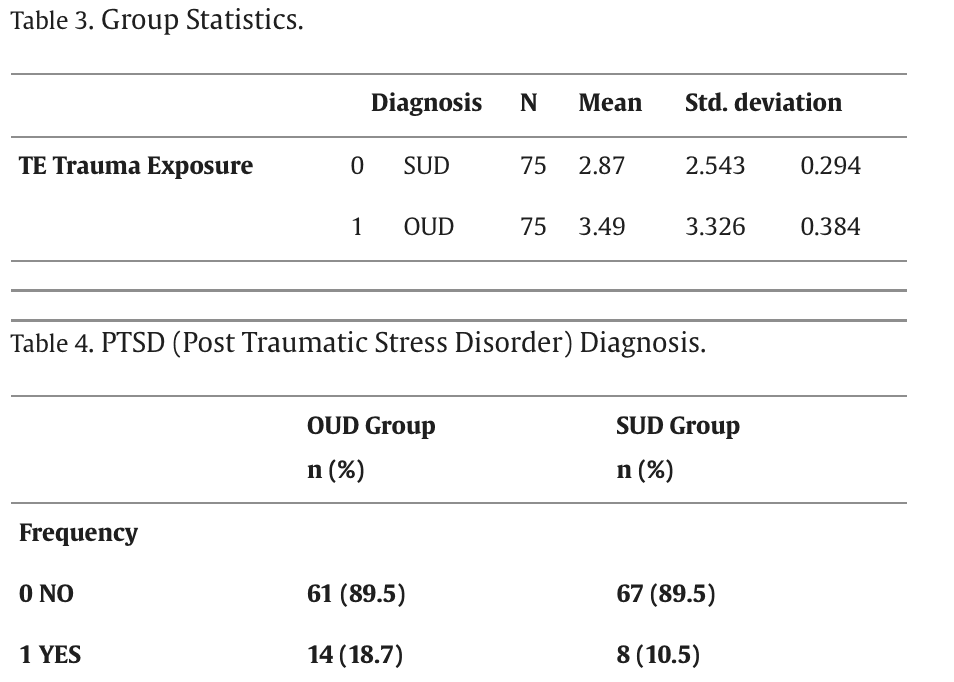

As noted in Table 2, the majority of participants reported experiencing at least three traumatic events. There was not a significant difference in the PTE scores for OUD, N = 75 (M = 3.49, SD = 3.33) and SUD, N = 75 (M = 2.87, SD = 2.54); t (148) = −1.296, p = 0.98. However, these results suggest a trend that supports PTE may influence the occurrence of OUD, based on higher PTE mean scores in the OUD group when compared to the PTE mean scores in the SUD group (Table 3). Regarding the diagnosis of PTSD, there was not a significant difference in the number of participants diagnosed with PTSD in either OUD or SUD groups, Chi-Square (χ2 = 1.918, df = 1, p = 0.166) (Table 4).

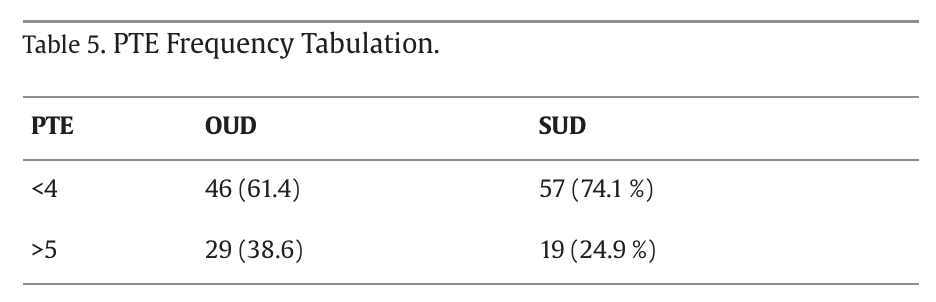

An odds ratio did not show a significant relationship in the trauma scores between the OUD and SUD groups, (χ2 = 1.684, df = 1, p = 0.194). However, a PTE score of > four is associated with a higher risk of poorer mental health outcomes (SAMHSA, 2018). A chi-square test of independence showed that there was no significant association of TE 0 < 4 between SUD and OUD groups, Chi-Square (χ2 = 1.407, df = 1, p = 0.236). Although, further scoring revealed that participants with PTE > five are more likely to develop OUD, Chi-Square (χ2 = 5.17, df = 1, p = 0.023). A frequency tabulation revealed that among clients with a TE > five, OUD was 38.6 % (N = 29), and SUD was 24.9 % (N = 19) respectively (see Table 5).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of psychological traumatic experiences (PTE) on the development of opiate use disorder (OUD) in an urban treatment facility in Pennsylvania.

Aim One: Demographic Findings

Demographic findings of OUD participants revealed a mean age of 37, 51 % female, and predominantly White. These results are consistent with prior research on OUD demographics in the U.S., showing that OUD treatment is associated with older age and Caucasian race (Brorson et al., 2013; Bullinger et al., 2022). However, our results regarding the number and percentage of African Americans in OUD treatment are not consistent with current research that indicates OUD rates are similar for both Blacks and Whites (3.5 % for Blacks, 4.7 % for Whites) or the community demographics for the study site (Gramlich, 2022; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020).

Aim Two: Trauma Exposure

Our results indicated that 75 % of OUD participants experienced one or more traumatic events. These results align with other studies (Rosic et al., 2021; Keyser-Marcus et al., 2016). However, the percentage of co-occurring PTSD diagnoses within the OUD (18.7 %) group was lower than expected when compared to other studies, which have reported that 41 % of OUD clients have a lifetime history of PTSD and 33.2 % meet the criteria for a current PTSD diagnosis (Dahlby and Kerr, 2020).

Aim Three: Influence of PTE on OUD

Our study found that PTE may influence the occurrence of OUD based on higher PTE mean scores in the OUD group than in the comparison SUD group. Study results were significant on the influence of PTE on OUD when TE > 5. These findings are in line with emerging studies. A recent study by Rosic et al. (2021) showed that trauma and PTSD are prevalent among patients with OUD, stressing the importance of integrating addiction and mental health services for this population. Furthermore, Santo et al. (2022) found that childhood trauma exposure was a common, independent risk factor for OUD.

Racial Disparities

The study's racial findings did not reflect the community demographics or the emerging post-pandemic demographic data on OUD prevalence. The study site's community demographics report a 69 % African American population and a 17 % Caucasian population. Therefore, one would expect the racial makeup of study participants to reflect the community demographics and the study's racial demographics to be higher than the national average. Possible disparities may exist within the pool of available jail court referrals for OUD treatment, indicating that persons of color may be incarcerated rather than offered OUD treatment in place of incarceration. Other possibilities include ineffective or lack of community marketing of services at the Drug & Alcohol unit, implicit bias, and community mistrust. This phenomenon supports future research on when and where these disparities occur.

Unexpected Findings

The lack of a significant association between PTE and OUD in some of the analyses is unexpected, given previous research on PTE and SUD. Several factors may have contributed to this finding, including the small sample size and underreporting of PTE and PTSD in the sample data.

Implications

Measuring PTE in persons with OUD is crucial for the formulation of targeted interventions that support high-quality outcomes for individuals and families recovering from OUD. Our study found higher PTE scores in persons with OUD, emphasizing the importance of identifying PTE and PTSD and implementing trauma-based and trauma-informed strategies during OUD treatment planning. This study also indicated that the small number of PTSD diagnoses observed in the OUD sample is inconsistent with public domain statistics and prior research on PTSD and SUD, highlighting the need for structured evaluations for the assessment and diagnosis of PTSD as a best practice initiative.

Limitations

Our study limitations include threats to the internal validity selection of subjects. This study used a convenience sample of two groups from a single site, limiting its generalizability to that site. Although selection bias did not occur, random sampling and random assignment to groups may increase the possibility of result generalization to other populations. This study also used a descriptive retrospective design, which fits with the scheme of available studies and fills the gap of the lack of studies on the influence of PTE on OUD. Although this design establishes precedence, causality cannot be determined. Finally, the study's limitations include the use of paper medical records that required hand data collection and tabulation.

Implications for Future Research

Implications for future research from this study include examining how PTE predicts OUD using a larger sample size, either as a descriptive design with broader generalization, correlational, or experimental study. Further research is also needed on social determinants of health (e.g., housing and food instability, community violence, adverse childhood experiences) and disparities among OUD individuals. Future research should also expand on other outcome variables that are important to the OUD population and use a site with electronic medical records for data collection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found evidence of a significant relationship between PTE > 5 and OUD, as well as some insignificant findings. While these insignificant findings may seem counterintuitive given existing research on PTE and SUD, they do underscore the complex nature of the relationship. Further research is needed to better understand these phenomena.