Abstract

Purpose Risk-taking is thought to peak during adolescence, but most prior studies have relied on small convenience samples lacking participant diversity. This study tested the generalizability of adolescent self-reported risk-taking propensity across a comprehensive set of participant-level social, environmental, and psychological factors.

Methods Data (N = 1,005,421) from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health were used to test the developmental timing and magnitude of risk-taking propensity and its link to alcohol and cannabis use across 19 subgroups defined via sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, population density, religious affiliation, and mental health.

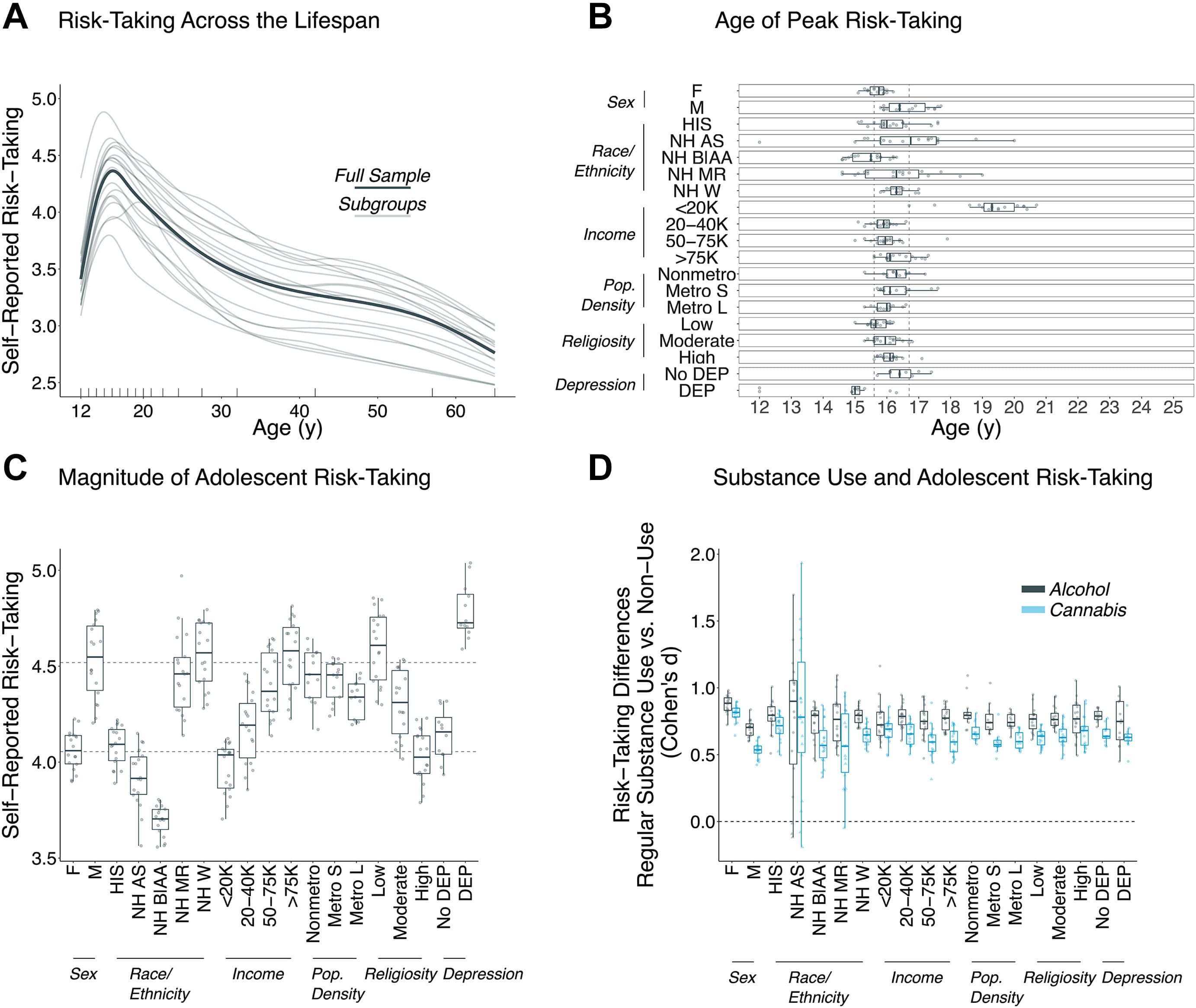

Results The developmental timing of a lifespan peak in risk-taking propensity during adolescence (15–18 years old) generalized across nearly all levels of social, environmental, and psychological factors, whereas the magnitude of this peak widely varied. Nearly all adolescents with regular substance use reported higher levels of risk-taking propensity.

Discussion Results support a broad generalizability of adolescence as the peak lifespan period of self-reported risk-taking but emphasize the importance of participant-level factors in determining the specific magnitude of reported risk-taking.

Adolescence, particularly mid- to late-adolescence (15–20 years old), is considered to be the period of the lifespan with the highest risk-taking and sensation-seeking behaviors [1,2]. While likely adaptive (e.g., promoting independence from caregivers) [1], this lifespan peak in risk-taking confers vulnerability to accidental fatalities and substance use disorders [1,2]. Prior large-scale epidemiological research has examined population patterns and social determinants of adolescent substance use [3]. However, most prior research on dispositional measures of adolescent risk-taking propensity and sensation-seeking, precursors to substance use and thought to be more generally relevant to all adolescents [2,4], has relied on relatively small university-based convenience samples lacking participant diversity in social, environmental, and psychological experiences. Thus, the generalizability and inclusivity of current theories of adolescent risk-taking and its associated vulnerabilities remain unknown. Clarity on the real-world generalizability of this theory is essential to current efforts to address youth mental health [5], through for example, identifying broadly applicable developmental periods for intervention and prevention efforts and the increasing number of targeted studies of adolescent risk-taking and substance use (e.g., Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, ABCD [6]). Toward current field-wide goals of 1) explicitly testing the generalizability of mechanisms of health and disease across diverse populations [7] and 2) establishing inclusive theories of mental health risk in youth [8], the current project used national survey data to test the generalizability of adolescent peaks in self-reported risk-taking propensity and its link to substance use across a comprehensive set of participant-level social, environmental, and psychological factors (19 total subgroups defined via levels of biological sex at birth, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, population density, religious affiliation, and mental health).

Methods

Public data (N = 1,005,421) were drawn from the 2002–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), an annual survey representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian population (12-years-old and older) of the United States. NSDUH procedures were approved by the RTI International Institutional Review Board, and participants provided informed oral consent.

Linear and nonlinear (spline) models were fit to a self-reported risk-taking propensity measure, consistent with prior work with NSDUH [9] and also supporting inferences from related work in adults [10] (sum score of two items: “[I] get a kick out of doing things that are dangerous”, [I] like to test [myself] by doing risky things”; association among scores: φc = 0.587; see Supplementary Material). Leveraging the very large size and participant diversity of the NSDUH data and with the goal of informing future smaller targeted studies of adolescence with expanded risk-taking and sensation-seeking metrics, variation in this risk-taking propensity measure was independently examined across a comprehensive set of participant-level factors (biological sex at birth, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, population density, religious affiliation, and mental health; 19 total population subgroups). Through this framework, primary study aims were to characterize the generalizability across social, environmental, and psychological factors of (1) lifespan peaks in self-reported risk-taking propensity during adolescence (ages at peak risk-taking determined via nonlinear lifespan trajectories) and (2) the association between adolescent risk-taking and regular (at least weekly; see Supplementary Material) alcohol and cannabis use. To ensure reproducibility and robustness, models were run on individual NSDUH study years, and inferences were drawn on results that reproduced across independently assessed NSDUH years (2002–2019). NSDUH guidelines for inclusion by study year are reflected in population density and depression-defined subgroups only using a subset of NSDUH years. All other analyses included all 18 years of NSDUH data. See Table S1 for a complete list of analysis variables, corresponding NSDUH variable names, and frequencies. All statistical models were run in R version 4.2 with the survey package version 4.1, which used analysis weights, replicates, and stratum distributed with public access data from the 2002–2019 NSDUH to account for the complex survey design.

Results

Replicating basic science studies of adolescent development [1], self-reported risk-taking propensity followed a nonlinear trajectory across the lifespan, with a robust peak during mid-adolescence (∼16-years-old) for the full sample (Figure 1A). Importantly, however, expanding this foundational work to consider a wide range of participant-level social, environmental, and psychological factors, independent models assessing the 19 population subgroups demonstrate a high degree of generalizability of this mid-adolescent peak, with 18 of 19 subgroups having peaks (median across NSDUH years) in risk-taking propensity occurring between 15 and 18 years old (Figure 1B; 87.3% of all NSDUH year by subgroup combinations). In contrast, the magnitude of the peak (average value from 15–18 years old) in self-reported risk-taking propensity widely and significantly varied (p's < .05 corrected [for 6 comparison categories], uncorrected p < .008) by population subgroup (Figure 1C). For example, adolescent males reported higher risk-taking propensity than females, and white adolescent participants reported higher risk-taking propensity than other racial/ethnic groups (Figure 1C). However, across all population subgroups, higher levels of self-reported risk-taking propensity between 15–18 years old significantly (p's < .05 corrected, uncorrected p < .003) disambiguated adolescents who regularly (weekly; see Supplementary Material) use cannabis or alcohol from non-using adolescents, with a high degree of consistency and generalizability in the magnitude of these differences (Figure 1D). A broader, graded pattern of self-reported risk-taking propensity differences was observed when comparing both adolescents specifically, as well as the full sample of participants, among those with regular substance use, nonregular use, and nonuse (see Supplementary Material).

Figure 1 Self-reported adolescent risk-taking propensity across population subgroups in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (A) Nonlinear lifespan models averaged across 2002–2019 NSDUH of self-reported risk-taking for the full sample (all participants; dark line) and for 19 population subgroups, analyzed individually (light lines). Vertical tick marks on x-axis indicate coded ages available in public NSDUH dataset (Supplementary Material). (B) Age of peak risk-taking (maximum value from nonlinear fit) from individual subgroup models from (A). Each dot indicates one NSDUH study year (2002–2019). Eighteen out of 19 population subgroups have an average peak (median across NSDUH years) between 15–18 years old, 87.3% of all year by subgroup combinations. Dashed line indicates range of year-to-year variability from the full sample. (C) Magnitude of adolescent (15–18 years old) self-reported risk-taking by subgroup. Dashed line indicates range of year-to-year variability. Apart from population density, omnibus differences among all population subgroups within a given category (sex, race/ethnicity, income, religious affiliation, depression) were statistically significant (p < .05, corrected [for six comparison categories]; uncorrected p < .008) across all NSDUH study years. (D) Standardized differences (Cohen's [d]) on self-reported risk-taking between adolescents (15–18 years old) who report weekly (or more) alcohol (dark blue) or cannabis (light blue) use compared to non-using adolescents for each population subgroup, adjusted for all remaining variables (see Supplementary Material). Circles display NSDUH year by subgroup combinations with corrected significance for users greater than nonusers (91.1% of all combinations for cannabis, 94.6% for alcohol; p < .05 corrected [for 19 population subgroups], uncorrected p < .003). Triangles display effects that do not exceed this significance threshold. Dashed line indicates 0 (no effect).

Discussion

We demonstrate that a lifespan peak in self-reported risk-taking propensity during adolescence and its link to substance use is generalizable and independently observed across a comprehensive set of social, environmental, and psychological participant-level characteristics, including subgroups based on biological sex at birth, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, population density, religious affiliation, and mental health. This work thus supports the potential broad applicability and real-world utility of intervention and prevention efforts that build from central theories emphasizing risk-taking as a general vulnerability factor (e.g., for substance use) for adolescents [1–3,11]. In parallel with models that highlight ongoing development of cognitive processes [12], the generalizability of observed lifespan peaks in risk-taking propensity during adolescence may help clarify broadly applicable but developmentally specific behavioral features through which to tailor intervention and prevention efforts. Importantly, however, unlike the developmental timing, the magnitude of adolescent risk-taking notably varies across individuals according to relevant social, environmental, and psychological factors, with patterns that mirror results seen in adults [10,13]. Such response patterns and engagement in self-reported risk-taking for an individual adolescent that vary according to contextual factors highlights the value of personalized approaches to assessment and intervention [14]. Future work expanding these efforts towards personalized approaches should also consider intersectional perspectives (multiple, overlapping identities within an individual that may be related to historical patterns of inequity, marginalization, and racism) that are particularly relevant for culturally and equity-informed assessment, intervention, and policy related to adolescent health [15].

Limitations of this study include the use of brief self-report data. Such brief risk-taking items embedded within very large, population-representative surveys allowed the current project to test the generalizability of adolescent risk-taking propensity across a comprehensive set of participant-level social, environmental, and psychological factors that have not been possible in prior smaller targeted studies of adolescent risk-taking. The insights from the current work are supported by recapitulating prior observations of adolescent peaks in risk-taking propensity, an association with substance use, and population patterns from adults. Nevertheless, the insights from the current work should be expanded with comprehensive self-report and objective measures in future targeted studies. We suggest that complementary approaches in targeted studies of adolescence and the large-scale, representative national survey data presented here provide a well-suited means towards addressing growing concerns regarding reproducibility and generalizability in developmental sciences [16,17], as well as to foster additional studies on risk-taking measurement. For example, in line with previous work, we note that dispositional measures of risk-taking propensity and sensation-seeking appear only moderately associated with behavioral manifestations of risk-taking [18]. Expanding the current results with multiple levels of analysis (e.g., neuroimaging, simultaneous behavioral and clinical assessments [19]) and timescales (e.g., ecological momentary assessment [20]) will likewise support improved rigor and reproducibility.

In summary, the current project leveraged large-scale (N > 1 million) national survey data to test the generalizability of a foundational theory of the adolescent period. Results demonstrated that across 19 independent subgroups spanning levels of key social, environmental, and psychological factors, mid- to late-adolescence is consistently the period of the lifespan with the highest self-reported risk-taking behaviors, and these may confer risk to substance use. Future work with complementary, targeted cohort studies of adolescence and large-scale, representative data can further refine these results and accelerate generalizable and inclusive translation of developmentally informed intervention and prevention efforts.