Abstract

New models integrating clinic-based care with community-based services for people with substance use disorder could reduce the time to stable remission and support recovery.

It’s been more than 50 years since the United States launched a "war on drugs." History has demonstrated the ineffectiveness of "tough-on-crime" drug-use policies, including laws requiring mandatory minimum sentencing for possession of illicit drugs. Meanwhile, advances in the recognition of substance use disorder (SUD) as a treatable medical condition have led to the development of lifesaving evidence-based pharmacotherapies and psychosocial interventions.

Further advancement in treating SUD will require both shortterm and long-term strategies. Many evidence-based protocols still rely on short-term interventions typically delivered over 12 weeks. But increasing the likelihood of sustained remission often requires years of complementary efforts addressing broader social needs alongside ongoing clinical care.

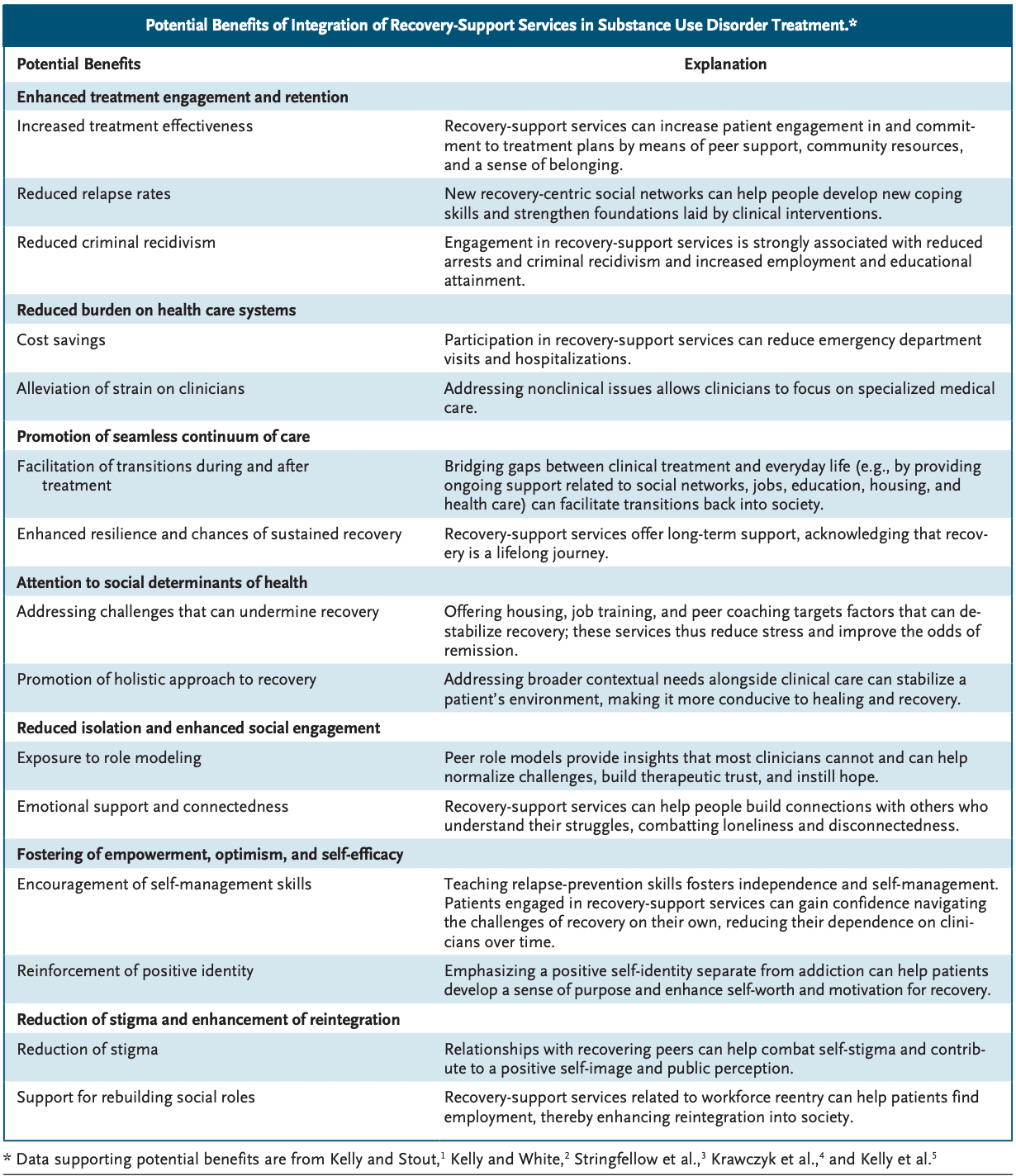

People remain at risk for SUD recurrence for years after initial remission.1 After treatment initiation, it takes people an average of about 8 years — and four or five treatment or support-group engagements — to achieve sustained remission and an additional 5 years before their risk of meeting SUD criteria drops to that among members of the general public. Addiction treatment has therefore broadened to encompass a continuity-of-care–based approach that builds on extensive advances in clinical treatments (e.g., extended-release medication for opioid use disorder [MOUD]) and includes long-term recovery support in the community. New models integrating clinic-based care with community-based services provide a more holistic approach that could reduce the time to stable remission and support recovery.

When a person with SUD enters treatment, the situation may be likened to a building on fire, with clinicians implementing critical short-term interventions to extinguish the flames. After the fire is out, however, attention to scaffolding and building materials is necessary for people with SUD to rebuild their lives in a safer and more secure environment that helps prevent the fire from restarting. Policies focused on criminalization of drug use, such as those leading to arrests for drug possession, can block access to the “permits” and materials needed to begin rebuilding (e.g., by increasing the chance that people will be denied employment and educational opportunities). Linkage to supportive environments and long-term services that provide access to this kind of “recovery capital” can enhance “fireproofing” by creating conditions that facilitate healing and resilience and reduce the risk of SUD recurrence.

A growing array of highly cost-effective, community-based recovery-support services in the United States is helping to catalyze and sustain long-term healing. These services include online and in-person offerings from mutual-aid organizations (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and Women for Sobriety), recovery-coaching or peerbased services that help connect patients treated in emergency departments (EDs) to clinical and community programs, recovery street outreach programs, mobile clinics, overdose-prevention sites, EDs, treatment courts, SUD clinics, and primary care offices — vary widely, the active therapeutic ingredients are similar across settings. Such services and venues are organized by and populated with peers in recovery from SUD who can inspire patients and instill hope, model recovery pathways, provide emotional and structural support, and share emotionregulation and other coping skills.

New research confirms the value of recovery-support services as extensions of clinical services. Peercoaching models, for example, can bolster the historically suboptimal uptake and long-term use of MOUD (at least half of patients discontinue use within 6 months). initial remission. The Overdose Prevention Strategy of the Department of Health and Human Services recommends recovery-support services for this purpose. Peer workers are often reexposed to SUD-conditioned triggers, however, and trauma-informed peer supervision and other institutional supports may be needed to sustain these models.

A Cochrane review of studies of interventions for primary alcohol use disorder, which one of us coauthored, found that clinical linkage to mutual-aid recoverysupport services leads to rates of continuous abstinence and remission that are 20 to 60% higher over 3 years than those achieved with other evidence-based treatments (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy). Widely implementing such services could reduce U.S. health care costs by an estimated $15 billion per year. Similarly, over a 2-year period, people with SUD who were randomly assigned to live in recovery residences were 52% more likely to be in remission and 86% less likely to have been involved in the criminal legal system than those assigned to live at home and receive usual SUD services and were 57% more likely to be employed; placement in recovery residences generated an estimated $30,000 in savings per person over the 2 years.

Such clinic–community integration could accelerate healing among people with SUD and help more people join the ranks of the 23 million or so adults living in recovery in the United States (9.1% of the adult population). Quality of life and functioning among people who have access to a one-stop shop for recovery resources and services provided by peer recovery support centers become equivalent to those among members of the general public after an average of approximately 5 years (rather than the average of 15 years observed in previous studies among people in recovery). Clinical and peer-based support services are being integrated at the city (e.g., Philadelphia) and state (e.g., Connecticut) levels, which has led to clinical, public health, and economic efficiencies.

Positive findings from these initiatives have inspired proposed legislation that would require appropriation of at least 10% of federal SUD block-grant funding to implementation of recoverysupport services and the establishment in 2021 of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Office of Recovery. Medicaid and state departments of public or mental health are increasingly paying for services such as recovery coaching, although such funding remains suboptimal and should be increased. Stigma and custom continue to lead to underpayment of both the recovery-support and clinical SUD workforces, and role definitions and quality and performance benchmarks for recovery-support services are needed to improve reimbursement structures.

The 2024 White House National Drug Control Strategy embraced greater interagency collaboration to expand payment for these services, but the extent to which the new federal administration will maintain this approach is unclear. Further evidence on recoverysupport services should be forthcoming; the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in partnership with other National Institutes of Health sponsors, recently launched the Recovery Research Networks initiative to establish multistakeholder groups to build infrastructure, train researchers, and document effective approaches in this area.

These developments mark a new phase in society’s understanding of SUD. During the past 50 years, approaches for addressing SUD have shifted away from the criminal legal system to the clinic — and they are now shifting toward greater clinic–community integration. Although additional drug-policy reforms are critical, and there have been examples of re-criminalization and public health policy reversals, these shifts reinforce the need to continue to build on clinical stabilization and other medical interventions. Incorporating recovery-support services as a component of SUD treatment infrastructure is essential. Doing so could help reduce people’s susceptibility to SUD recurrence by keeping the fire extinguished and increase the odds that some of the most vulnerable members of society will not only survive, but ultimately thrive.