Abstract

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) has been recognized as a chronic, relapsing disorder. However, much of existing SUD care remains based in an acute care model that focuses on clinical stabilization and discharge, failing to address the longer-term needs of people in recovery from addiction. The high rates of client’s disengagement and attrition across the continuum of care highlight the need to identify and overcome the obstacles that people face at each stage of the treatment and recovery process. Peer recovery support services (PRSS) show promise in helping people initiate, pursue, and sustain long-term recovery from substance-related problems. Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, the goal of this article is to explore the possible roles of peers along the SUD care continuum and their potential to improve engagement in care by targeting specific barriers that prevent people from successfully transitioning from one stage to the next leading eventually to full recovery. A multidimensional framework of SUD care continuum was developed based on the adapted model of opioid use disorder cascade of care and recovery stages, within which the barriers known to be associated with each stage of the continuum were matched with the existing evidence of effectiveness of specific PRSSs. With this conceptual paper, we are hoping to show how PRSSs can become a complementary and integrated part of the system of care, which is an essential step toward improving the continuity of care and health outcomes.

Introduction

Severe substance use disorders (SUD) have been recognized as chronic, relapsing disorders from which people can recover and lead productive lives through long-term treatment, continuing care, and recovery support.1-5 The substantial change in understanding the nature of addiction as a chronic rather than an acute illness or a moral failure calls for a change in social perceptions, substance use prevention, treatment, and outcome expectations.2,6

Existing SUD treatment approaches are still largely based in intensive or acute care models that focus on reducing symptoms, clinical stabilization, and subsequent discharge. Single, unlinked treatment episodes are followed by brief “aftercare” services, upon which treatment relationships end and the person is expected to achieve long-term recovery on their own.7,8 As such, this model of care seems unable to address the needs of people in recovery from severe and chronic SUD who often go through several episodes of care and cycles of remission, relapse, and treatment reentry before achieving sustained recovery.9-11 Unsuccessful outcomes of this model identified at different stages—such as difficulty engaging in treatment, lack of referral to the next step in the continuum of care, high rates of treatment dropout and relapse, and disconnection from post-treatment services—demonstrate the need to shift from the acute care model to a chronic care model of SUD treatment and to better integrate services across treatment modalities.7,8,12

Recognizing this long-standing treatment gap, recent calls have been made to develop a comprehensive SUD prevention and care continuum as a tool to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness and quality of healthcare delivery by estimating the proportion of people progressing over time through sequential steps along a continuum.13,14 A similar cascade of care for HIV was successfully developed and applied to track people from the moment they are diagnosed with HIV to achieving sustained viral suppression, highlighting the main gaps in healthcare along the way.15 Based on this model, Williams and colleagues developed the Cascade of Care for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), a framework which identifies critical gaps in care and informs the development of targeted interventions. Application of this model allows measurement and improvement in the quality of OUD healthcare services and population health outcomes.16,17 This model reflects clients’ attrition across all the stages, from prevention and diagnosis, to treatment engagement, initiation of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), treatment retention, and remission.16 Unlike the HIV cascade of care, the official data to populate most of the steps of the hypothetical cascade of care for any SUD embedded in a recovery-oriented system of care are lacking.14 However, the gaps between current care and recommended treatment goals are evident from the research.

Many people who are at risk for developing SUD often go untreated although they could benefit from secondary prevention, early screening and, if needed, connection to services.16,18 The official data for 2018 show that in the U.S. among the 21.2 million people diagnosed with SUD who needed treatment, only 11% actually received it at a specialty facility (i.e., a hospital, a drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility, or a mental health center).19 Furthermore, even when this small proportion of people diagnosed with SUD gets connected to services and initiates some kind of specialty treatment, low treatment retention is a major barrier that stands in the way of maximizing treatment benefits and is associated with increased relapse, readmissions, and mortality.12,20 Finally, among the people who do complete SUD treatment, roughly half of them resume their drug use within a year of discharge and are rarely connected to aftercare services.7

These findings show that the long process of care is prone to major disengagement and attrition and how challenging it is to provide continuing care without losing people down the road or delaying their progress through sequential stages, which can have detrimental and sometimes fatal consequences for the person. Once these gaps in care are identified, there is an urgent need to identify the underlying barriers that people with SUD face at each stage of care and recovery, leading to the development of ways to overcome them and improve continuity of care.

Recovery Support Services

In contrast to the currently dominant acute care model, a sustained recovery management model of SUD treatment takes into account the relapsing and chronic nature of addiction.21-24 At the core of this model is the need for continuing care and helping people get and stay engaged in a full continuum of care until achieving sustained recovery. Sustained recovery management is a framework for “organizing treatment and recovery support services to enhance early pre-recovery engagement, recovery initiation, long-term recovery maintenance, and the quality of personal/family life in long-term recovery”.24 It seeks to extend recovery support beyond the stabilization of the clinical symptoms and offer on-going recovery support across different stages of the care continuum and recovery.7 This is especially important for the people who have low recovery capital, including low resources and motivation to engage and stay in recovery.25,26 With the shift from acute care to the sustained recovery management model, SUD services would focus on achieving long-term recovery of their clients as their ultimate goal. In practical terms, significant changes in the continuum of care would need to be made, including intensifying the outreach and linkage efforts, enhancing motivation for change in the pretreatment phase, intensifying in-treatment recovery support services to enhance treatment retention and adherence, and providing assertive linkage to communities of recovery during and after treatment.7,22

A key component of the Sustained Recovery Management Model is Peer Recovery Support Services (PRSS), one of the most widely implemented types of recovery support services. Peer Recovery support is non-clinical assistance by persons with lived experience of similar conditions to initiate, pursue, and sustain a person’s long-term recovery from SUD.27 The core competencies of the peer specialists in this process are to promote hope and motivation for change by sharing their lived experience of recovery, establish a caring and collaborative relationship with their peers, support their recovery planning, and link them to available resources and supports. They also provide help in situations of crisis, build the skills to enhance recovery, and promote advocacy and personal growth.28 These services are provided in a variety of settings and are designed to support people through different stages of recovery before, during, and after treatment. This is why their service roles can vary from outreach and engagement to recovery coaching, case management, supplemental medical and social services, to recovery checkups.27

The current evidence speaks to the promise of PRSS improving access, retention in care, and other treatment and recovery outcomes.29,30 By focusing on long-term recovery rather than being limited to medical stabilization and remission, PRSS have the potential to be complementary and an integrated part of the SUD continuum of care.27,31 In order to know how these services should look and when to offer them, we need to know about people’s needs and the obstacles they are facing in the process of recovery and in receiving healthcare. A qualitative study showed that people’s priorities and needs change at different stages of recovery, indicating that there are factors beyond achieving abstinence that are necessary pillars of recovery, such as employment, family/social relations, and housing.32

Based on a comprehensive review of the literature, the goal of this article is to explore the possible roles of PRSS across the SUD care continuum, and their potential in closing the treatment gap by helping people meet their needs and overcome specific individual, social, and environmental barriers generally known to be associated with each stage of the continuum. We develop a multidimensional framework of SUD care continuum based on the adapted model of OUD cascade of care and recovery stages, within which we will match the known barriers at each stage of the continuum with the current evidence of effectiveness of specific PRSS.

Methods

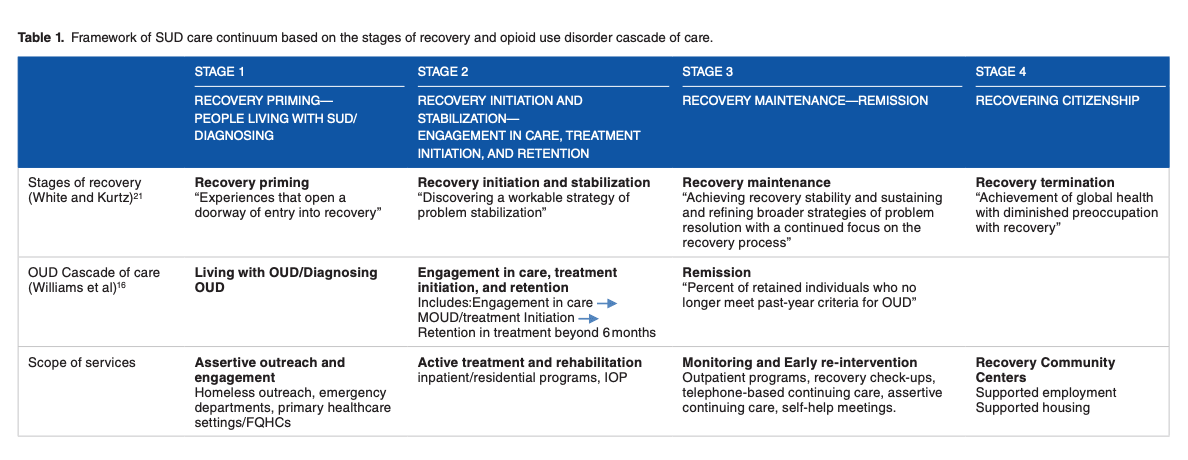

To set the basis for our multidimensional framework of SUD care continuum, we matched the stages of recovery33 with the stages of the adapted OUD cascade of care16 based on the authors’ operating definitions of each stage (Table 1). For the purpose of this article, we are focusing on people who are living with SUD, both those who may be undiagnosed and in need of treatment as well as those diagnosed with SUD. Therefore, we will adapt the OUD cascade of care to the purpose of the article and disregard the prevention stages of this model. Following the last stage of the OUD cascade of care defined as remission, we will describe an additional stage of recovering citizenship as the ultimate goal of the SUD continuum of care. Overall, we define 4 stages of our model and acknowledge that the proposed SUD continuum is not a linear process for many people, as it is prone to attrition, skipping and overlapping of different stages, and reengaging in care. Next, to reflect gaps in the SUD continuum of care, we turn to the available literature and national survey data for some insight about the prevalence and dropout rates at different stages of care. After that, we map the factors that are generally documented in the literature as barriers onto each stage of care and recovery. Finally, we look at the existing evidence on PRSS to see how peer support can target these barriers and improve transition from one stage of the care continuum to the next until achieving stable recovery.

Table 1. Framework of SUD care continuum based on the stages of recovery and opioid use disorder cascade of care

Stage1: Recovery Priming—People Living With SUD/Diagnosing

The first stage of our framework is recovery priming, defined as “experiences that open a doorway of entry into recovery.”33 This stage corresponds to the first few stages of the OUD cascade of care, in which people are undiagnosed or unaware of their substance use problems or when they are diagnosed with SUD but not linked to health care for a variety of reasons. In an effective continuum of care, people who are in need of care and are in a pre-recovery stage need to be successfully connected to treatment services and supports in order to initiate their recovery process. The scope of services provided at this stage are typically assertive outreach and engagement of persons with alcohol and substance use problems.

Official data from the 2018 national survey show that only 11% of people with SUD received specialty treatment, indicating suboptimal outreach and engagement of the population of people who need care.19 The same trend is seen for people with co-occurring disorders, among whom only 7% received both substance use and mental health care, with almost half of them receiving no care at all.19 It also indicated that 95% of those who did not receive SUD specialty care did not feel that they needed it in the first place.19 Published research has shown that the majority of people drop out in the first couple of steps of the enrollment process.34 The 45% of people who make the call requesting services do not make it to their first assessment appointment, whereas an additional 32% of them dropout after completing their intake assessment, failing to enroll in the program or initiate the actual treatment.34 These findings show that there is a major gap in the continuum of care in the pre-treatment phase, highlighting disconnection from the healthcare system and the importance of offering outreach to people in need of SUD treatment and increasing efforts in engaging them in care.

The main factor that the NSDUH survey identifies as a barrier to receiving SUD treatment among people with SUD was not feeling the need for treatment in the first place.19 However, among a very small proportion of the national sample who did not receive treatment despite perceiving the need for it, the main barriers include not being ready to stop using and not being able to afford expensive treatment without healthcare coverage. Other barriers include the lack of knowledge and information about where to get treatment, as well as fear of stigma at the workplace and in the community.19,35

Waitlists and appointment scheduling delays,36-38 presence of a comorbid psychiatric condition,37,39,40 recent history of arrests,40 unemployment and economic barriers,41 homelessness,42,43 and lack of childcare and transportation35 are all factors identified as barriers to engagement in treatment services and recovery initiation.

Many of these disabling factors seem to be more pronounced among women with SUD who are less likely over their lifetime to enter care as compared to their male counterparts.44 Some of the specific barriers to treatment entry that women face include pregnancy, lack of services for pregnant women, fear of losing child custody, fear of prosecution, lack of childcare, trauma histories, and greater social stigma compared to men.44

Research has documented that minorities are less likely to engage in substance use care. Although readiness to enter treatment did not differ by race, Blacks were least likely to report contact with any treatment modality, including detox, compared to Latino and White populations.45 An important qualitative study by Venner and colleagues35 looked into the barriers that Native Americans face in order to seek treatment and support for alcohol-related problems. Besides many of the generalizable barriers already mentioned, this study revealed important obstacles specific to this population, with the majority of participants identifying a mismatch between the already limited treatment options available and their own cultural beliefs and preferences.

Taking all of this into consideration, there is no doubt that people need significant support and close guidance right at the beginning of their recovery journey. A growing body of evidence highlights the importance and potential of PRSS to overcome many of the barriers at this stage. Results of a pilot study of substance use in rural women with HIV, for example, suggest that a brief peer-counseling intervention may increase participants’ acknowledgment that their alcohol and other substance use is problematic and their readiness to take steps towards achieving sobriety.46 Kamon and Turner47 report that people receiving help from peer recovery coaches at one of Vermont Recovery Network’s peer-run Recovery Centers scored better on multiple dimensions of recovery capital, including services, housing, health, social, family, substance use treatments, and mental health and legal outcomes. They also had higher motivation to become and stay abstinent compared to the time before receiving recovery coaching. They report that working with recovery coaches changed their pattern of using medical services, by decreasing the use of intensive levels of care and increasing access to primary care services that are more viable and cost-effective for the system.47 Peer recovery coaches can also be helpful in bridging the child welfare system and substance use treatment by providing outreach, engagement, and navigation services to parents and caregivers during the first 60 days of their referral to treatment.48 The group referred to the program with peer support was reached more easily for the initial appointment and initiated services quicker and at a higher rate than the group who received the standard program without peer support.48

Several studies have looked at the impact of peer outreach to meet people generally disconnected from the system. Peer-led outreach mobile intervention had a positive impact in facilitating access and utilization of SUD treatment services, specifically detox and residential programs, among female sex workers who use drugs.49 Similarly, assertive peer outreach efforts to identify active opioid users in urban areas, engage them in conversation about heroin use and the possibilities of treatment, have been shown to be effective for linking active opioid users to detox and MOUD treatment.50 In the emergency department setting, peers’ conversations about readiness to change and risk factors, and their support in the process of linkage to MOUD treatment, resulted in shorter median time to initiation of MOUD among people who survived an opioid overdose.51

Stage 2: Recovery Initiation and Stabilization—Engagement in Care, Treatment Initiation, and Retention

The second stage of our model is recovery initiation and stabilization that entails “discovering a workable strategy of problem stabilization”33 paired with the OUD cascade of care stages of engagement in care, treatment initiation, and retention.16 The scope of service provided in this stage of the care continuum typically include active treatment and rehabilitation in inpatient/residential and intensive outpatient settings.

Even when people are connected to services, staying in treatment until completion poses a significant challenge on its own. Treatment retention has been consistently reported over the years to be a universal challenge across different care settings.12,20,52 Dropout rates vary significantly by population treated, substance of choice, and treatment characteristics.12 They range between 20-70% for inpatient programs,53 23-50% for outpatient programs,20 and around 50% for office-based opioid treatment programs.54 It is extremely important to improve the rates of treatment retention and completion as it represents the achievement of personal recovery goals and is associated with reducing substance use, mortality and relapse while increasing quality of life and social functioning.12,20,52,55

There are a number of factors that act as barriers to treatment retention. Having psychiatric co-morbidity is associated with not only higher odds of treatment dropout but also shorter stays in treatment.56-58 Demographic characteristics such as younger age,54,59-61 homelessness,62 having a history of physical or sexual abuse,63 unemployment, Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity, and being positive for Hepatitis C54,61,64,65 have all been associated with early disengagement from substance use treatment. Insufficient or lack of functional social support from families, friends, and faith communities66,67 and continued substance and polydrug use58 have all been found to be predictors of early treatment dropout.

Several qualitative studies reveal clients’ reasons for treatment cessation. One study suggests that the most common reason for disengagement from buprenorphine treatment is an involuntary discharge due to disagreement with program staff (cited by 17% of clients), or lack of adherence to program rules and expectations, such as insufficient attendance (17%) and drug positive urines (9%).59 Another common reason that might explain issues with attendance is perceived inflexibility of the program and its incompatibility with life obligations (17%).59 Both clients and clinicians agree that limited connection with the program staff (i.e., weak therapeutic alliance), as well as clients’ lack of motivation and readiness for change pose significant obstacles to staying in treatment.66,68-70 The absence of daily activities, the lack of emotional support, and learning how to deal with negative feelings during treatment have been shown to be particularly important for young adults who are in treatment.71 In relation to that, it has been shown that greater use of positive coping strategies is a significant predictor of longer stay in treatment.72

There is limited research on the role and impact that PRSS might have on treatment retention, completion, and overcoming common barriers in this stage. The findings from the Texas Access to Recovery program for a criminal justice population showed that longer treatment retention and higher completion were associated with the provision of direct recovery support services, including individual recovery coaching, relapse prevention group, recovery support group, spiritual support group, life skills group, and marital/family counseling in combination with treatment.73 Furthermore, Blondell and colleagues found that a brief single-session peer counseling intervention during detox treatment resulted in greater likelihood of treatment completion and clients not leaving against medical advice.74 The 60 days of peer support for substance-using parents as part of their referral process to substance use care increased the length of stay in treatment, but did not increase treatment completion, indicating perhaps that longer presence of peer support and guidance is needed for optimal outcomes.48 One study looked at the effects of peer-provided case management on treatment relationship and engagement early in the treatment process for clients with severe mental illness, among whom 70% had a co-occurring SUD.75 It was found that clients perceived higher positive regard, understanding, and acceptance from peer providers than from regular case managers, which in turn predicted higher motivation for treatment and attendance of AA/NA meetings.75

Stage 3: Recovery Maintenance—Remission

The next stage of the care continuum covers the phase right after treatment completion and discharge. It is defined as Recovery Maintenance, that implies “achieving recovery stability and sustaining and refining broader strategies of problem resolution with a continued focus on the recovery process.”21 The Recovery Maintenance stage corresponds to Remission, as the last stage of the proposed OUD cascade of care defined as “percent of retained individuals who no longer meet past-year criteria for OUD.”16 The primary goal at this stage is to effectively transfer people after completing an initial phase of higher intensity treatment (usually residential or intensive outpatient) to some form of lower intensity continuing care, also known as “stepdown care” or “aftercare”76,77. This is a stage in which they would receive active support in their recovery efforts and change of lifestyle.

Given the chronic and relapsing nature of severe SUDs, continuing to provide care and support after treatment is necessary to maintain the benefits of the initial phase of care, enhance quality of life and adherence,78 prevent relapses, and thereby reduce the likelihood of treatment reentry.8,77,79 The scope of continuing care services necessary in this stage includes monitoring and early re-intervention via recovery management checkups,9 assertive continuing care,80,81 telephone-based continuing care,82,83 and self-help meetings,77 as well as other types of recovery support.8

Even though it is well known that over half of people relapse in the first 3 months following treatment discharge,84,85 the connection to aftercare services that could help people sustain long-term recovery is low or non-existent.7,76,86 In the absence of official data on the national level, the dropout rates from continuing care are inconsistent among studies, ranging from 25% to 90%.8

Among the reasons for such low engagement in continuing care is the passive referral process and lack of proactive staff efforts to connect people who are leaving treatment to aftercare services. These referrals are often times limited to staff verbal encouragement and rely on people’s motivation to follow the recommendations to attend these sessions.8 In addition, most people who leave treatment early, against medical advice, or get discharged from the program do not receive referrals to continuing care sessions as part of their discharge plan. This lowers even more the likelihood of their initiating continuing care.87

Although the research on predictors of aftercare participation are largely inconsistent, some studies have found that higher geographical distance to the location of continuing care services88 and low pre-treatment motivation89 represent obstacles to connecting with these services. On the contrary, longer duration of initial residential treatment and higher satisfaction with it emerged as positive factors for attending 12-step and individual counseling aftercare.90

Several studies looked into the role that PRSS could play in a more proactive referral process to continuing care. Timko and colleagues conducted a series of studies comparing intensive to standard referrals of clients in outpatient programs to 12-step groups. Intensive referrals, which involved counselors connecting people with 12-step peer volunteers for active guidance and companionship, resulted in higher attendance and involvement in 12-step groups, and better substance use outcomes than a standard referral procedure involving only verbal encouragement and information about the meeting schedule.91-93 These findings align with the previous study indicating that systematic encouragement and community access facilitated by peers has an important role and is a much more successful strategy to connect people from outpatient programs to AA meetings.94 A study by Manning and colleagues also showed that active referral strategies during inpatient treatment are more effective in increasing client’s post-discharge attendance of 12-step programs. This was especially the case if the referral is provided by 12-step peers sharing their own experience with the program, compared to the doctors providing a referral.95 These findings show how important it is to connect people to aftercare services while they are still in higher intensity treatment. They also highlight peers’ potential to help people overcome initial prejudice about self-help groups by sharing their own experience of participating in them as an example of a successful recovery story.

A body of evidence shows that having peer support during inpatient treatment increases chances of successful recovery upon discharge. A brief peer counseling intervention during detox is associated with increased self-help group attendance after discharge and initiation of professional outpatient care following the referral.74 Furthermore, adding peer social engagement and support to the conventional care for people with co-occurring psychiatric and SUDs significantly increases people’s levels of relatedness, social functioning, self-criticism,96 and engagement in outpatient care following inpatient discharge, compared to receiving treatment as usual.96-98 One study showed that people with co-occurring disorders who participated in the Friends Connection peer-led support program had longer community tenure (i.e., periods of living in the community without rehospitalization) than a comparison group.99

Different types of recovery community programs and recovery community centers (RCC) have been developed recently by the recovery community itself as an additional setting for providing peer recovery support and in response to community needs. Early findings are promising, in that this model could serve as an organizing community hub for providing peer-to-peer activities and a variety of recovery and support services to the people at different stages of care and recovery – “from engagement and increasing readiness to stabilizing recovery and sustaining and growing recovery”.100 Preliminary data from two PRO-ACT RCCs show improvements in housing and employment and mitigation of mental health symptoms.100 In 2016, a hybrid model of RCC was developed to provide both recovery coaching and harm reduction services, such as syringe exchange. 101 The preliminary evaluation showed that this model could be a feasible and effective way to engage people who inject drugs.101 Additionally, an American Indian community-driven program has shown that attendance at voluntary self-help groups and support from family and friends increased as a result of PRSS.102 Service users also reported gains in important components of recovery, including stable housing, employment, and improved health during the 6-month participation in this program.102 The community recovery maintenance program, PROSPER, encompasses an array of peer-to-peer social support activities for people in recovery who have been incarcerated. It showed excellent results for participants who had increased self-efficacy, perceived social support, quality of life, and decreased perceived stress.103

Stage 4: Recovering Citizenship

As part of people achieving sustained recovery and remaining separated from substance use social dynamics, they need to return to the local community within which they might have disrupted relationships, and within which they have been stigmatized.104 Therefore, recovery from addiction includes not only achieving diagnostic remission of symptoms and global health, but also “rediscovery or development of an authentic self, a reconnection or reformulation of family, and a new social contract with one’s community and culture.”104

With this in mind, we choose to define the last stage of our model as Recovering Citizenship, suggesting that by enabling people to have responsibilities, roles, rights, resources, relationships (the “5 R’s”) and a sense of belonging in the community, they are afforded opportunities to recover within society rather than outside of it.105 We believe that having spaces where people can participate, contribute, and exercise full citizenship while striving to achieve this stage of recovery is crucial for ending social marginalization and breaking intergenerational patterns of detrimental substance use.

Several long-term follow-up studies obtained data on recovery prevalence that vary from 30% to 70% depending on the study sample characteristics and criteria for recovery.22 Some people with the most severe and chronic SUD may need guidance in reconnecting to society and regaining the 5 R’s. Very few studies available have explored the role of PRSS in this process. Rowe and colleagues106 compared a citizenship intervention, consisting of a group component and a peer support component, with standard services for persons with criminal justice histories and co-occurring serious mental illness and SUDs who were participating in outpatient programs. Although the effect of peer support could not be independently analyzed in this study, they found that the participants of the citizenship program had significantly reduced their alcohol use over 6 and 12-month periods when compared to standard treatment alone.106 But most importantly, they achieved significant changes in their lives in the community, such as getting a job or becoming recovery leaders and advocates themselves.107 Another example of a program that envisions citizenship as an essential stage of recovery is the “Recovery Association Project” in Portland, Oregon whose peer services were offered to support the development of effective citizenship skills through leadership training, reducing stigma around recovery, and providing a range of supports to sustain individual recovery.108 The program showed high satisfaction among the participants and ability to sustain recovery by significantly reducing their substance use and relapse 6 months after program participation.

In this last stage of recovery, RCCs are places where people in recovery through their work as peer mentors play a valuable role by sharing their knowledge, skills, and lived experience with their peers in need of recovery support. This is a position that allows them to practice their citizenship and establish a new social identity as an insider rather than an outsider, as a community asset rather than a community burden.104

Discussion

It is well known that engaging and retaining people in the SUD continuum of care is a challenging process prone to disengagement and attrition. The Sustained Recovery Management model, and in particular PRSS, are focused on the need for providing continuing care and helping people get and stay engaged in a full continuum of care until achieving sustained recovery. The present article intends to contribute a practical way of thinking about PRSS as targeted interventions, meant to address people’s needs and barriers at each stage of the SUD care continuum, and as an integrated part of substance use services. In order to know how PRSS should look and when to offer them, we need to be aware not only of where the major gaps in the cascade of care occur, but also what the underlying factors are that contribute to these gaps. Both of these components should be able to inform the development of targeted peer support interventions for recovery from SUDs. Understanding the roles and benefits of peer support is even more important in the light of the recent efforts to widely implement and professionalize peer supports, as indicated by state-level certifications for recovery coaches across the country, as well as the fact that PRSS are becoming billable through Medicaid and other payors.

In general, we found ample evidence that peer recovery support is successful in closing these gaps and helping people transition from one stage of the care continuum to another by addressing some of the barriers that people face. The available evidence shows that PRSS are especially effective in the initial stage of recovery priming, by increasing people’s risk perception of negative consequences of harmful substance use, their readiness and motivation for change, their recovery capital, and ultimately by helping them take the first steps to starting treatment. However, we could benefit from more research on culturally and gender-specific PRSS in order to address many of the barriers that minorities and women in particular are facing in the initial stages of treatment and recovery initiation.

Despite low treatment retention and completion rates and a number of known predictors of early treatment dropout, including a number of demographic and program characteristics, we conclude that more research is needed that would explore the role and potential of PRSS in fostering treatment alliances and overcoming obstacles that individuals in treatment face.

Furthermore, PRSS seem to be a successful alternative approach to standard medical referral after discharge. However, more research is needed on the specific barriers to continuing care as well as the mechanisms of action of peer support in this stage of care. We also need more insight into peers’ roles in helping people in recovering citizenship, as the last stage and an ultimate goal of the SUD continuum of care.

Based on the review of the literature, being a minority, having psychiatric comorbidity, low motivation and readiness for change, and lacking basic resources such as housing, employment or transportation are common factors of treatment disengagement across the care continuum. We note that more research is needed in developing and implementing PRSS interventions to target especially these barriers. In addition, we described the evidence of how integration of PRSS could address barriers in the continuum of care for both OUD as well as other SUDs (e.g., linkage to MOUD for people with OUD vs. connecting people to mutual support groups for alcohol and other substance use). We acknowledge that there are important differences worth exploring in the ways peers can support people who use different types of substances.

Research in the mental health field has identified several mechanisms by which links between peer support and positive outcomes are established. Instillation of hope through positive self-disclosure, role modeling of self-care, and navigation of services are among the most important mechanisms of action of PRSS for people with mental illness.75,109 In other words, peers instill hope that recovery is possible, offer their own example of successful recovery and foster people’s self-efficacy, and finally show them how to do it and what resources are available to them.109 In addition to these, we believe that there is at least one more mechanism of action specifically applicable and relevant to SUDs in the recovery priming stage, where people need help with acknowledging and understanding their substance use as problematic prior to finding the strength and willingness to take first steps to overcome it.

In this paper, we are bringing together two bodies of literature and two different approaches to responding to SUD that rarely communicate or refer to each other’s findings: the medical approach that focuses on symptoms and has as an ultimate goal improvement of clinical outcomes, and the recovery approach that looks beyond individual clinical stabilization and focuses on a broader social context in which both addiction and recovery take place, with increased quality of life and functioning as an ultimate goal of SUD treatment. While we acknowledge that individuals seldom experience recovery as a linear process that therefore cannot be captured in stages, the substance use field is operating on a stage-based model for services that need to be oriented to certain discrete tasks. In this context, we show that discrete phases of recovery are compatible and aligned with the stages of the recently developed OUD cascade of care, a necessary tool to systematically evaluate the quality of healthcare delivery at a population level. By doing so, we counter the common perception of recovery as something that comes only after medical treatment. Aligned with previous views, we show that recovery starts with the first glimpse of one’s acknowledgment of having a substance use problem and wanting to do something about it, and it arguably ends with achieving sobriety and “enhanced quality of personal family life in long-term recovery.”24

By showing that these two models are compatible, and with the pending task of developing a SUD cascade of care, we are hoping that this paper contributes to the discussion of what kind of outcomes we want to use to reflect the quality of a healthcare system for SUD and to set its targets. The way we define a successful healthcare system should go well beyond medical completion, appointment attendance, or adherence to program rules, as these measures do not provide significant information about recovery, improved quality of life, and enhanced functioning in the community where likely lie the triggers of relapse. If we limit our efforts to achieving medical remission only, we would be forgetting the importance of structural changes in one’s life in the community that need to happen in order to break the cycle of addiction, such as being back with one’s family, getting a job and stable housing, completing education, etc. Our position is that besides reduction or elimination of symptoms, other indices of recovery should be included in order to evaluate the impact healthcare systems can have for people with SUD as the field moves steadily towards achieving a fully recovery-oriented system of care.110,111