Abstract

## Background and objectives Planning and implementing prison-based substance use disorder (SUD) interventions are challenging. We wanted to understand why and how people in correctional settings (CS) use drugs and to explore what policies, environmental, and interpersonal factors influence substance use among incarcerated people. Using the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) framework, we proposed a thematic map with intervention functions to reduce substance use in CS.

## Methods We used the Framework Method of qualitative analysis. We did snowball sampling for the incarcerated people with drug use (PWD) and convenience sampling for the staff. The in-depth interview sample comprised 17 adult PWD, three prison administrative, and two healthcare staff. We determined the sample size by thematic data saturation. We followed a mixed coding approach for generating categories, i.e., deductive (based on the BCW framework) and inductive. The study constructed the final theoretical framework by determining the properties of the categories and relationships among the categories.

## Results We identified eleven categories aligned with the BCW framework. The themes were prison routine, interpersonal dynamics of the incarcerated population, exposure to substance use, attitude of staff towards PWD, experience with prison healthcare, willingness (to reduce drug use) and coping, compassion, drug use harms, conflict between staff and residents, stigma, and family/peer support. The BCW framework aided the identification of potential intervention functions and their interactions with the organizational policies that could influence PWD's capability-opportunity-motivation (COM) and drug use behavior (B).

## Conclusion There is a need to raise awareness of SUD prevention and intervention among decision-makers and revisit the prison policies.

Highlights

Substance use in correctional settings has personal, interpersonal, social, structural, and policy-level determinants.

Behavior change wheel (BCW) provides a framework for understanding substance use in prison context.

We identified potential intervention functions and their interaction with organizational structure and policy.

Our analysis revealed the scope of peer and family engagement in the care of people who use drugs in prisons.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) in correctional settings is 3 to 4 times that of the general population (Fazel et al., 2017). Criminalization of drug use and possession, drug-related offenses, and re-incarceration contribute to the higher rates of SUD in correctional facilities (Factors linked to reoffending: a one-year follow-up of prisoners who took part in the Resettlement Surveys 2001, 2003 and 2004-NICCO, n.d). Nonetheless, the relationship between drug use and crime is complex and non-linear (de Andrade, 2018). The incarcerated population who uses drugs/alcohol (PWD) during incarceration have a higher risk of contracting and transmitting blood-borne and other infections, not only while in the prisons but after release into the community (Azbel & Altice, 2018; Baussano et al., 2010; Larney et al., 2018). They also have higher odds of death due to overdose and other causes following prison release (Binswanger et al., 2007; Farrell & Marsden, 2008). Substance use might threaten the security and stability of the prison and increase the risk of violence in prisons.

Previous research showed that prison-based treatment of SUD might reduce substance use, chances of relapse, and reoffending (Pearson & Lipton, 1999). However, the primary studies for this meta-analysis were from North America and Western Europe. Another narrative review of studies on behavioral interventions for incarcerated females with mental illness did not find evidence of effectiveness (Perry et al., 2019). Nevertheless, some interventions, such as the opioid agonist maintenance treatment (OAMT), have been shown to reduce drug use and high-risk behavior within the prisons, reduce the risk of drug overdose mortality, and increase engagement in treatment after prison release (Hedrich et al., 2012).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that its member states provide evidence-based, right-based treatment in custodial settings. They consider prison health a component and continuum of public health (International Standards for the Treatment of Drug Use Disorders, n.d). Therefore, the International Standard for treating SUD and universal health coverage must also apply to PWD (International Standards for the Treatment of Drug Use Disorders, n.d).

Despite the health and social burden, preliminary evidence of effectiveness, and an international mandate to provide high-standard healthcare in prison settings, access to evidence-based SUD treatment is limited, even in high-income countries (Prison and drugs in Europe: current and future challenges, 2021; National Academies of Sciences, 2019). Data is largely unavailable from low and middle-income countries (LMIC). According to a report from nine South American countries, only 1–20 % of prisoners had access to mental health treatment (Almanzar et al., 2015). However, the authors did not specify SUD treatment. Data from the World Mental Health Survey suggested that 1 % of people who use drugs/alcohol receive minimally evidence-based treatment for SUD in the LMIC (Degenhardt et al., 2017). When the availability and access to SUD treatment are severely limited in the community, one would imagine the access to be further restricted in the prisons. The reasons for the reluctance to provide access to SUD treatment must be investigated.

The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) is a behavior change intervention framework that helps design interventions for behavior change in a specified population. The BCW framework helps researchers identify intervention functions and organizational policies that can change behavior (Michie et al., 2011). The BCW framework posits that to engage in (or disengage from) a behavior (B), a person must be psychologically and physically capable (C), and have opportunities (O) and motivations (M) to do such behavior. Interventions, structural changes, and policy measures facilitate (or challenge) behavior change by influencing capability, opportunity, and motivation. The BCW framework has been used successfully to understand and improve hearing aids, antibiotic use, and COVID-19-related health/social behaviors in specific populations (Barker et al., 2016; Duan et al., 2020).

We used the BCW framework and COM-B model to understand substance use behavior (why and how people in correctional facilities use drugs) and to explore what organizational policies, external environment, and interpersonal factors influence substance use among incarcerated people. Finally, we proposed a thematic map with intervention functions to reduce substance use in correctional settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Research team and reflexivity

We had a multidisciplinary research team of psychiatrists (AG, DB, PKM), social workers (RRP, DS, RN), and public health experts (PKM, JV). The supervisors (AG, PKM, RRP, and DB) had more than ten years of qualitative research experience, and the research staff (DS, RN, JV) had at least two years of research/clinical experience. All supervisors were MD, Ph.D., or both; the research staff had at least a master's degree in their respective fields. All research staff were women. For four months, they received induction and experiential training (e.g., conducted pilot interviews and analysis) on qualitative research. All research staff lived in the accommodation provided by the prison administration and conducted interviews within the prison settings. We conducted six training sessions for the prison medical staff and met the prison administration to establish working relationships and collaboration. The research staff interacted, explained the research goals, and developed rapport before conducting in-depth interviews (IDI). None in the research team was directly involved in the care/treatment of participants or the organizational decision-making. The team ensured the participants' privacy and confidentiality owing to the research topic's sensitive nature and the prison context. Our study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India (IEC 03/2021-1916).

2.2. Study design

2.2.1. Theoretical framework

We used a Framework Method of qualitative analysis. The Framework Method is a systematic method of categorizing and organizing qualitative data using deductive and inductive approaches. We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines for reporting our methods and results (Tong et al., 2007).

2.2.2. Participant selection and setting

There were two groups of participants- prisoners with drug use and prison staff. We did snowball sampling for the individuals with drug use and convenience sampling for the staff. The latter ensured representations from medical and administrative staff. All participants were approached face-to-face; no one refused to participate in the study. The final sample for the IDI comprised 17 adult incarcerated participants with substance use, three prison administrative staff, and two healthcare workers. We excluded participants with severe mental illness and cognitive impairments. The study obtained medical details from prison health records. The study was done in a single-central prison in Haryana (a north Indian state). The prison can house 1500 people. However, during the research, there were around 1200 residents. More than 80 % of them were under trial. The correctional facility has one health center with two nurses, one pharmacist and technician, and two medical graduate doctors who work on alternate days. The health center has a 20-bed inpatient facility. The medical doctors were not trained to deliver SUD treatment. Opioid agonist maintenance treatment (OAMT) was not available.

The study conducted interviews in May 2022.

2.2.3. Data collection

The first step was generating the interview guide. AG, JV, RN, and DS had a brainstorming session to enlist the topics and questions, keeping the BCW framework and research question in mind. In the next stage, we excluded redundant questions, and grouped and arranged similar questions to ensure a natural flow of the interview. Finally, we consulted the BCW framework again to avoid leaving out potential topics. We also ensured the questions were open-ended and simple, and “controversial/challenging” questions were kept at the end. PKM, RRP, and DB then gave feedback on the interview guide. The study prepared the final guide after two iterations by incorporating comments from other authors. Please see Supplementary 1. The study audio recorded interviews. The research staff also kept field notes to record additional impressions and analytic thoughts. At the beginning of the interview, researchers asked participants to briefly provide demographic and substance use details. After that, researchers followed the interview guide. The duration of IDIs was approximately 45 min. Research staff prepared transcripts of the interviews, which aided in data immersion. We adhered to thematic data saturation principles. JV checked all transcripts. However, transcripts were not returned to the participants for their comments/corrections.

2.2.4. Data analysis

The analysis was conducted by JV and RN, who also performed the data IDIs and transcription (n = 11). After familiarization with the data, JV and RN performed coding of the transcribed substantive content, values, and emotions. We followed a mixed coding approach, i.e., deductive (based on the BCW framework) and inductive (any new emerging codes). At the initial stage, the researchers coded ten IDI transcripts line-by-line. They used descriptive, in-vivo, and process coding. The inter-rater agreement between JV and RN was estimated as kappa 0.644 (p < .0001). The level of agreement was moderate. They combined common and recurrent codes and formed categories aligned with the BCW framework. AG examined the coding and categories; face-to-face discussions with AG resolved the discrepancies between JV and RN. AG generated a code dictionary. JV and RN re-examined the data, refined the codes/categories, and labelled them with descriptive phrases. Subsequent coding was based on the code dictionary; however, the research team recorded and discussed new emergent codes with AG. We used the Delve software for the coding/analysis. This software aided in charting the voluminous data and included references to the illustrative quotations.

Based on the BCW, we constructed the final theoretical framework by determining the properties of the categories and relationships among the categories through discussion and consensus between JV, RN, and AG. A narrative summary described the components of the theoretical framework, and other members of the research team and supervisors reviewed and verified the summary.

3. Results

The study recruited seventeen (17) incarcerated participants with a history of current (n = 12) or past drug (n = 2) and alcohol (n = 3) use. Most of them reported polysubstance use. Some used opioids (n = 9), cannabis (n = 4), and alcohol (n = 8). The mean duration of substance use was 28 months. The mean age of the participants was 28.6 years; the mean prison stay was 18 months (range 4–36 months). Some participants were imprisoned for crimes related to their drug use, a few committed crimes unrelated to their drug use, and one was sentenced under narcotics drug law. All incarcerated participants were men. This was not as per the study design, but the male: female to male ratio in prison was 30:1. We could not find incarcerated females with substance use. Among the participants, 12 were under trial, and five had received their prison sentences. We also interviewed three prison administrators and two healthcare staff. They were in service for a mean duration of 12 years.

We identified eleven categories (themes) aligned with the BCW theoretical framework.

3.1. Prison routine

Participants described their daily routine at the prison. We identified monotony in the routine. The day starts with personal hygiene activities and breakfast. A few prison residents would visit places of worship, while others prayed in barracks. Some residents kept themselves busy by cooking food in the barracks.

“I wake up at 11 a.m. to take a bath. I visit Gurudwara inside the jail. Barracks are closed by 12 pm. Then, the gates open at 3 p.m. We go to the canteen and work at the factory. I cook my food with the groceries my family provides.”

(IDI_IN_3)

Participants shared their views regarding their daily routines. They expressed boredom and lamented the limited number of activities available, incentives, and autonomy. A few participants work at the canteen while others work at the bakery. They were paid Rs.30-40 INR (0.36-0.48 USD) daily for their work. Money was directly credited to their accounts to avoid “misuse.” However, prison residents would use this money to purchase basic amenities from the jail canteen.

“I exercise daily; I have made dumbbells out of mud, and I use them for exercise; this helps me to pass my time in jail, but it is difficult; there are not many things to do.”

(IDI_IN_5)

One of the medical officers elaborated on the other avenues for engaging the prison population, such as tailoring, musical instruments, and the library. Occasionally, the prison administration organized cricket matches for prison residents. Although the narrative shared by the prison staff had some commonalities with those shared by the incarcerated participants, the account portrayed by the staff showed prison routine in a more positive light, which seemed to contradict somewhat the views shared by the incarcerated participants.

“The gurudwara is inside the prison premises. They can go to the Gurudwara. They go to the temple. There is also a library and a school inside. There is also another music school. There are all kinds of musical instruments there in the music school. So, everyone is free. They can do whatever they want while they are incarcerated.”

(IDI_PO_1)

3.2. Dynamics of prison life/life in prison

An incarcerated person's life in jail is governed by rigid rules that direct how they eat, sleep, and socialize. To understand the life of an incarcerated person, it is very important to explore interpersonal prison dynamics. In prison, people meet, spend time together, and share an emotional bond with fellow incarcerated people. They develop a brotherhood and listen to each other with a we-feeling; the peer network might influence substance use behavior.

“It is an impact of company one keeps. Like brotherhood, some would not like to indulge in the wrong activities. They prefer physical activities, such as jogging; they would go to gyms, etc. Whoever stays with such a person may follow the same schedule and learn similarly.”

(IDI_ _IN_04)

A new prison entrant must integrate into a group in the prison community. The integration requires conformity with the groups' norms and loyalty to the group members (Drake et al., 2014). Therefore, substance use in a particular group might influence the behavior of the incarcerated population who want to be affiliated with such groups. On the other hand, people who used drugs before incarceration were inclined to select a group that fostered substance use.

“If a person uses a substance, he would encourage others to try it. He motivates the other person to try it once and says he will enjoy it a lot! If the other person does it once or twice, they will start liking it and develop a habit.”

(IDI_ IN_04)

According to one of the jail administrators, there is bullying among the incarcerated population. Some command, while others follow their commands. Similarly, a few gangs and leaders purposefully involved “innocent inmates” in drug use. Once they develop SUD, the “leaders” would manipulate them to do forced labor.

“There are these leader guys who will lure people to get addicted to drugs and alcohol; they give them drugs for free till the other person becomes habitual. Then, the leader guys will make them do their chores, such as washing clothes.”

(IDI _PO_02)

“One inmate provides drugs to another. He persuades the other to consume it once or twice. When the other person gets addicted to the drug, he is forced to fulfill the wish of the one who gets him drugs. Like this, several inmates get addicted and get into trouble, they do all these to earn money, and innocents who were not into this also fall prey to this.”

(IDI_PO_03)

3.3. Exposure to and practice of substance use

Incarcerated participants had varied reasons for substance use. Some participants with drug use problems have mentioned that drugs benefitted them. They were stress-free and could sleep after taking drugs. Although some wanted to stop, they failed because of cravings and social isolation.

“I get a nice sleep- no tension, no worry”

(IDI_IN_06)

“It is not good for my health. I want to stop, but I cannot. I have the urge to do it. I feel alone, away from family; I have no friends. But I need to change my mind.”

(IDI_IN_04)

“The problem is, my body was tremulous, and I could not sleep if I did not take drugs. I was feeling restless; there was so much depression! I was sweating severely. So, I contacted one boy here, and now I take drugs whenever needed.”

(IDI_IN_01)

Some participants mentioned having less access to substances inside the prisons. However, they claimed drugs were available at a higher cost (than in the community) and were more adulterated. Therefore, they would require increasing the quantity, further increasing the cost. Adulteration and higher doses might have more harmful consequences. Some manage to access drugs when they go out for court hearings.

“Not even rich people can afford to continue using substances; they use 2gm heroin a day and keep on increasing the quantity; they keep on increasing potency and quantity, which cost them more than ten thousand rupees per day; who can afford that?”

(IDI_IN_04)

“Due to this heavy dose, bad quality of drugs or continuous consumption, they get seizures.”

(IDI_PO_02)

Inside the prison, incarcerated people could earn 8000 (USD ∼100) per month. Although this was meant for buying necessities, some people would use this for buying drugs and alcohol. Sometimes, the group helped each other to fund their substance use.

“I get access to cigarettes from the canteen. I get money and buy cigarettes and consume up to 7-8 cigarettes daily.”

(IDI_IN_12)

“Yes, sometimes family. Otherwise, my friend and I share the expenses to buy drugs. Someday he bears them, and on other days I do.”

(IDI_IN_02)

3.4. The attitude of prison administrators towards PWD

The views expressed by the staff ranged from caring/understanding to distant/disengaged or even hostile. Some staff held negative and stigmatizing views and used stigmatizing labels for PWD. Some conceived substance use as a voluntary and controllable behavior that an individual could choose to stop if they were willing to do it. They tacitly recommend an authoritarian approach to reduce substance misuse.

“Look, people with substance use can only be convinced with love; try to make them understand its consequences; if we shout at them, punish them, they would get angry, irritated, and aggressive and do the opposite of anything you say.”

(IDI_IN_03)

“Yes… they get drugs here in some or the other way; they climb up the walls somehow and manage to get it. Their thinking is so different from ours. These drug addicts are uneducated, so they do not understand the consequences of drug use.”

(IDI_PO_1)

“Not so many people give up, but some people are stubborn and do not listen.”

(IDI_PO_2)

3.5. Experience with prison healthcare

Most incarcerated populations lamented inadequate access to standard healthcare services and the unavailability of essential medications in the prisons. They complained about healthcare workers' attitudes towards PWD. The unavailability of opioid agonist maintenance treatment (OAMT) and inadequate linkage to hospital-based OAMT posed challenges in treating opioid use disorder.

“The services are enough here, but how they are delivered is not good. I have had dental issues since childhood, but they gave me a painkiller here. How does that help with dental caries? There is a way for everything.”

(IDI_IN_11)

“I go to PGI (public-funded hospital) for OST treatment. For the past 3 months, I visited 3 times for this treatment there.”

(IDI_IN_13)

“Sometimes we have to send inmates for outside consultation because most drugs are unavailable here, such as buprenorphine and OST therapy. These are not available at the local pharmacies. So, we send the inmates to a psychiatrist at the local hospitals. They can get medications from there.”

(IDI_PO_3)

One administrative staff complained about the limited availability of mental healthcare in the prisons and the lack of training for the existing staff to deal with mental health and drug use problems at the individual level.

“We face difficulties with inmates with mental health, stress issues. Anytime they can harm themselves. The chances are more when they use drugs.”

(IDI_PO_1)

3.6. Willingness and coping strategies

Some incarcerated participants were motivated to quit substances and willing to seek help for their substance use, but the limited availability of treatment thwarted their attempts.

“Mental health professionals play a very important role in motivating their clients to get rid of maladaptive behaviour and enable them to change it to positive one, but there is no one here.”

(IDI_PO_03)

“Through counselling, I would be able to quit substances.”

(IDI_IN_06)

“I will try to quit substance use and will not indulge in any crime.”

(IDI_IN_10)

A few believe they could stop using drugs after prison release; they thought social cues and relationships would affect their chances of drug use in the community.

“I know when I will go outside, I will leave it automatically.”

(IDI_IN_04)

“If I get the right companionship. I may try to quit substances.”

(IDI_IN_05)

3.7. Empathy and compassion

Perpetrators of crimes are assumed to have psychopathic traits, suggesting a general lack of empathy towards families and strangers (Skeem et al., 2011). In prison, people, despite being from different backgrounds, got involved with each other and shared an emotional bond. They would develop empathetic relationships with their fellows. They would help each other during crises and distress. They demonstrated components of affective and cognitive empathy.

“We took care of him because he was upset. He was mentally disturbed, so we cared for him……. we helped him bathe today… After that, we gave him food…. We listened to him and tried to make sense of what he said.”

(IDI_IN_03)

3.8. Consequences of substance use (drug use harms)

PWD experienced several drug use harms, direct or indirect. The direct consequences of substance use are health issues (mental and physical), personal issues, like family problems, and troubles in professional life. The indirect consequences of drug use are stress in family members, financial crisis, caregiving burden, and accidents. PWD in our study sample acknowledged drug-related harms to themselves and their families.

“For instance, whenever I feel heavy-hearted/emotional, I take drugs… then I hurt myself.”

(IDI_IN_10)

“Now I have to go and start from zero, now let us see because seven years have already passed inside, let's see when the release will be made, because earlier it was such that when I used to take drugs, my expenses, my family's expenses, could not be met, now it is that I have stopped….”

(IDI_IN_04)

One of the prison healthcare staff suggested how the knowledge of drug-related harms could be reflected during a counselling session; however, they did not specifically comment on the style of counselling- directive, authoritative vs. open, and empathetic.

“We tell him about the negative impact of substance use on them and what are the impacts on their family and how it causes a financial burden on them. And so, the patients are counselled in that way.”

(IDI_PO_01)

3.9. The conflict between prison administration and prison residents (prison administrator's experiences)

To prevent recidivism, staff-offender relationships and understanding and improving the prisoners' social situation are considered core issues (Järveläinen & Rantanen, 2019). The incarcerated participants expressed mixed views regarding their relationship with the prison staff. Some indicated a constant bargain between the prison residents and staff, whereas others discussed a non-understanding and non-supportive relationship. However, the staff contradicted the views expressed by the incarcerated participants with PWD, supported by instances to foster increased engagement with the incarcerated people. They seemed to categorize prison residents (good vs. bad) and might implement differential treatment for PWD.

“I behave properly so that they also behave cordially with me.”

(IDI_IN_07)

“They do not behave well. I am here, caught in jail; I attempted to kill myself three times. No one ever listens.”

(IDI_IN_08)

“Some inmates are good here. Inmates play cricket, and our superintendent also plays with them. Those using drugs are stubborn; they do not engage.”

(IDI_PO_02)

3.10. Stigma

Structural and public stigma against PWD frequently emerged during our discussions with the prison officials. Stigma is referred to as discrediting, devaluing, and shaming of PWDs because of their characteristics or attributes. Public stigma against PWD is fostered by believing that PWD can control their drug use, which is dangerous, and taking a moral approach to viewing PWD instead of a public health approach. Internalized stigma is when PWD tend to subscribe to the negative beliefs harboured by the general public. Incarceration adds to the stigmatizing experience. Sometimes, the behavior of healthcare workers generates a sense of shame and embarrassment in the PWD.

“If they do not get drugs, they may behave inappropriately with us as well; we do not spare them.”

(IDI_PO_01)

“Yes… they get drugs here in some or the other way; they climb up the walls somehow and manage to get it. Their thinking is so different from ours. These drug addicts are uneducated, so they do not understand the consequences of drug use.”

(IDI_PO_01)

“Not so many people give up, but some people are stubborn and do not listen.”

(IDI_MO_2)

“Few of them cuts their veins, they harm, and when they get into withdrawal, they do all kinds of these nasty things.”

(IDI_PO_03)

“They manipulate everyone. They somehow hide drugs with them and consume these later.”

(IDI_PO_03)

“Sometimes when we ask for medicines for our drug use, the doctors make us feel embarrassed.”

(IDI_IN_08)

3.11. Family and peer support

The need for family support frequently emerged during the IDIs.

“Mother, father, and everyone at home (sister) come to meet me. Attends phone calls twice daily, 5 minutes each.”

(IDI_IN_12)

“My sister meets me twice a month, and I call home twice for 5 minutes in the morning & 5 minutes in the evening.”

(IDI_IN_02)

One of the participants expressed concerns for the family and children. They expressed loneliness and longings to reunite with family members. Some incarcerated participants expressed disappointment and a sense of helplessness because of a limited chance of meeting family members.

“Sir, please get me out of jail! My life has been ruined; my wife has filed a complaint against me. I want to go outside to see my children. I always stare at the gate while sitting. I feel depressed sometimes; there is hardly enough sleep during the night. I eat whatever tablet I get from here. I mostly sleep after 1-2 hours of taking those pills.”

(IDI_IN_09)

“My mother usually comes here every 15-20 days. But now she is unwell, so I rarely call her.”

(IDI_IN_11)

“I met my wife once only. Later on; she died of illness.”

(IDI_IN_06)

However, interpersonal problems and negative comments from family members could trigger drug use in PWD.

“One day, I fought at home… My mother used to taunt me by telling me that I drink so much milk and eat ten bananas each day… she said, ‘what would you achieve by doing all this?’ This hurt me… After that day, I started using drugs. I started taking drugs if she did not want me to become anything.”

(IDI_IN_03)

“I went to meet them once… initially… My son was young. His maternal grandmother did not let me meet and commented, ‘You are dead to me.’ There was one incident… during a communal feast in 2018, I happened to cross paths with my wife and son. I tried talking to my wife and asked her to return, but she refused. I tried giving my son some money… he did not take it, and my son could not recognize me, and he said to his mother, ‘I am feeling hot here… let us go home’. I saw this and felt very uncomfortable; I thought, let me do drugs; no one wants me here.”

(IDI_IN_05)

3.12. Thematic Map

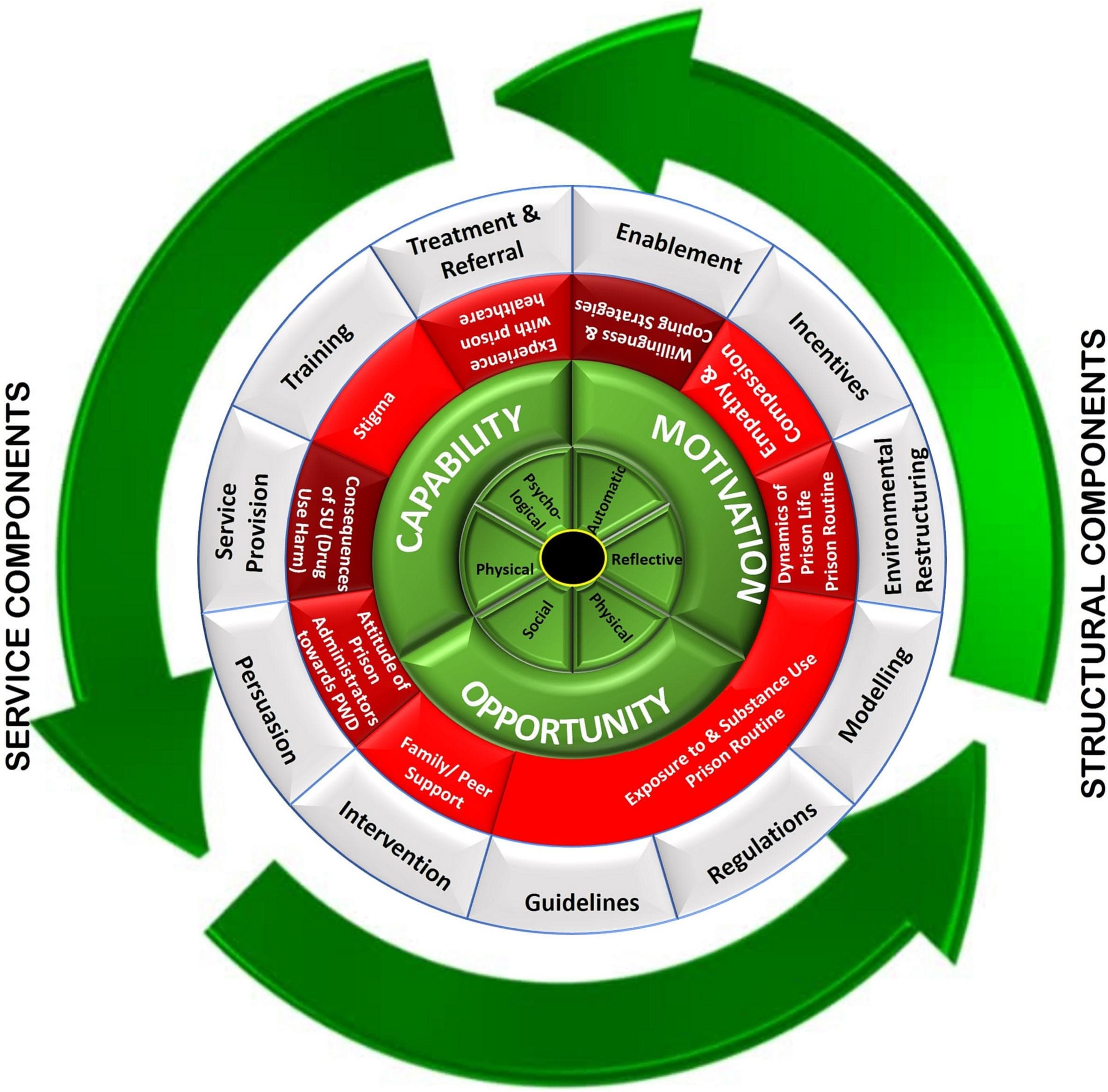

We used the BCW framework to explore the complex relationship between interventions directed at changing individual prison population's substance use and policies enacted by the authorities that might enable or prevent such behavior change (Michie et al., 2011). The themes derived from the qualitative analysis indicated the key roles of capability (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M) to bring about an individual's substance use behavior (B). Skills to address coping, stress, and stigma might enhance the capability. In contrast, reduced exposure, decreased availability of drug use, and increased peer/family support could enable an individual to initiate and sustain reduced substance use. Raising motivation at a personal level, interpersonal compassion/empathy, and engaging in prison routines might, directly and indirectly, influence people's motivation to change substance use. A prison policy that supports the structural and service components could facilitate the implementation of the COM-B at the individual level. Guidelines and regulations to limit the availability and risky practice of substance use, environmental restructuring to create an engaging prison routine, incentivization through a compassionate attitude towards prisoners, service provisions for treatment and harm reduction, and training of prison staff to deliver evidence, and right-based treatment for SUD, reduce stigma against PWD- were the key organizational and structural components to drive the individual-level change in substance use. Please see diagram 01 for the COM-B and prison policy components and their potential interactions to bring about an individual-level behavior change.

4. Discussion

Our qualitative framework analysis revealed eleven themes about the reasons and attitudes of the incarcerated participants for substance use and motivations for change; the analysis also revealed the perceptions of the prison administrative and healthcare staff towards substance use and PWD and their treatment. Additionally, we discovered interpersonal relationship and conflicts between the incarcerated participants and the prison staff. Using our thematic map and the BCW framework, we identified potential intervention functions and policy organizations that could influence components of COM and might reduce substance use behavior (B) in PWD (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Contextual characteristics and intervention strategies using the behavior change wheel framework.

Prison interventions to reduce substance use should be considered a complex intervention (Skivington et al., 2021); it is multi-component (individual, prison healthcare infrastructure, training of prison staff); it targets a range of behaviors (substance use and high-risk behavior in the prison population, facilitates engagement in prison routines); it focuses at multiple levels (skills training, reduced access to substances, and increased access to treatment for SUD, reduced structural and internalized stigma against PWD). Our analysis showed that contextual and individual-level variables to change substance use among the incarcerated population were interrelated and interdependent, suggesting that prison healthcare for PWD must be recognized as a complex system (Plsek & Greenhalgh, 2001). For instance, the reduction of substance use in PWD required raising individual-level awareness of harms due to drug use and motivation (the process of enactment), which must be enabled by the availability of motivational counselling and an operational prison healthcare system (dependent process), which further was dependent on a non-stigmatizing and public health-oriented disposition of the prison administration (dependent socio-cultural issues). Another example of the system's complexity could be the reduction in opioid use and risk behavior dependent on access to OAMT, which was further determined by the administration's attitude towards OAMT and treatment and policymakers' willingness to invest in prison healthcare.

No LMIC literature exists on the reasons and perceptions of substance use in correctional settings. No global literature has attempted to use the BCW framework to propose intervention functions and changes in organizational policies. Our study has addressed these knowledge gaps. Previous studies from the UK and Danish prisons showed how the custodial imperative of compliance with prison protocols, safe containment, and “zero tolerance” could come in conflict with the right-based and evidence-informed SUD treatment/care imperatives (Kolind et al., 2010; McIntosh & Saville, 2006). The article from Denmark additionally identified conflicts between the drug treatment providers and prison administrative staff imposing restrictions on the SUD treatment choice and disciplinary sanctions (Kolind et al., 2010). Our analysis also revealed interpersonal conflicts between PWD and prison staff and the overarching dominance of the custodial imperative reflected by punitive structural policy, limited access to medical care, antagonistic attitudes of prison staff, and constraints to engage the prison residents in a therapeutic mode. However, we identified empathetic peer relationships in PWD and the need for continued family support- unique to Indian settings. Strong family involvement in healthcare (and mental healthcare) and family-centered decision-making are characteristics of South Asian culture (Ito et al., 2012). Hence, our findings might also apply to other South Asian countries.

The strength of our study lies in our adherence to the reporting standard, reflexivity, transparency, sample and saturation, co-coding, and stakeholder engagement.

4.1. Implications

Our study showed that the research evaluation and implementation of interventions for substance use in prisons should adopt a complex intervention approach. At the individual level, access to psychosocial treatment to raise motivation and skill building to reduce drug use and medical treatment for withdrawal and OAMT, promote interpersonal compassion and empathy, access to an engaging prison routine, and need for the family and peer support were identified as critical components of prison-based SUD interventions. At the structural level, the essential components were improved interpersonal relationships between prison staff and PWD, reduced availability of drugs, provision of harm reduction and SUD treatment, and training to address structural stigma. Previous research on the effectiveness of interventions, such as cognitive behavior therapy, motivational interviewing, peer support, and network-based treatment, which are standard of care for community-based SUD interventions, showed mixed results (Stein et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2020;Newbury-Birch et al., 2018;Prendergast et al., 2017). We believe the reason for the divergence of evidence in prison vs. community settings is a result of the non-adoption of a complex intervention and systems perspective. This could also explain the sub-optimal implementation of prison-based SUD intervention programs (Prison and drugs in Europe: current and future challenges, 2021; National Academies of Sciences et al., 2019). Our study may encourage future researchers to plan, evaluate, and implement prison-based SUD intervention within a complex intervention framework. We understand that implementation of such intervention would be resource-intensive, and scaling up might be beyond the system's capacity, even in high-income countries (Kothari et al., 2002). In Indian settings (or in Southeast Asia), engaging PWD peer networks and family in the custodial SUD treatment process might be possible, which could partially address the resource constraints.

Our study showed prison administration must provide access to and evidence, and right-based preventative and treatment services for PWD. Alongside, mental health screening and treatment must also be incorporated. Although training and capacity building of prison healthcare staff is essential to make SUD care available and sustainable, a collaboration and linkage with community care providers will ensure care continuity post prison release. Collaboration with social agencies and peer networks will help with the isolation and discrimination reported by PWD and their rehabilitation and recovery after release.

We did not explore SU prevention in our research; however, our study suggests that early screening and brief interventions for those with substance misuse, and initiating treatment for those with preexisting SUD might prevent development of SUD and restarting substance use in prisons, respectively. Reducing access to illegal drugs and improving access to essential medications (e.g., OAMT) will complement and support SU prevention strategies.

4.2. Limitations

All participants in our study were men. Drug use among incarcerated women is prevalent and presents unique challenges, such as a higher stigma, association trauma, violence, and mental health problems. Thus, they need a prison policy that supports gender-sensitive care (Zurhold & Haasen, 2005). However, our study cannot provide insights into substance use behavior change in incarcertated females. Our study results reflected policies, service provisions, attitudes, and behavior of a single prison system from LMIC. Therefore, the results might not be generalizable to well-resourced settings from high-income countries. Although we used one of the most well-accepted and validated behavior change taxonomy, the BCW, researchers have argued that the variability between people, context, interventions, and their interactions has been neglected in BCW (Zurhold & Haasen, 2005). We did not co-create the codes and themes with the participants; we might have missed the unique perspectives and experiences of the PWD and prison staff in our themes and theoretical framework (Marlett et al., 2015; Ogden, 2016). Although an accepted methodology, data saturation to determine the sample size in qualitative research is based on an uncertain predictive claim on the non-emergence of new information that could only be tested if the data collection continued. We did not include prison policymakers and missed the top-down, bureaucratic viewpoints on substance use and policies to address the same; hence might have missed critical feedback on prison policy. The research participants could have provided more insights; however, the tendency to give socially desirable response from the prison staff to avoid conflicts (with the higher administration), participants' perception of policy changes as something very challenging to implement, and thus outside the purview of the discussion, and participants might have thought it was “not their job” to think and talk about policy changes- were a few potential reasons for not finding themes directly addressing prison policy. Nevertheless, the findings and implications of our study must be communicated to the prison policymakers to enable long-term structural and systemic changes in the CJS. Our analysis was restricted to measures to reduce substance use in prison; however, one must recognize that substance use, medical, and psychosocial issues persist after prison release, and there must be a continuity of prison and community healthcare (Hoffman et al., 2023). Our analysis did not explore aspects of post-prison-release. We did not examine the themes by under-trial vs. sentenced prisoners; they might have different concerns. Finally, the initiation and sustenance of these service and structural components would require funding, administrative, and logistical support from the policymakers. However, we did not include policymakers in this study.

4.3. Conclusion

Prison-based interventions to reduce drug use should use a complex intervention perspective targeting a range of behaviors at multiple levels. Effective implementation of such interventions requires understanding the beliefs, attitudes, and practices of the prison staff, healthcare system, and policymakers. The behavior change wheel (BCW) framework aided our understanding of substance use in correctional settings. The same framework might be helpful in planning, evaluating, and implementing prison-based SUD interventions in the future. There is an urgent need to raise awareness of SUD prevention and intervention among prison policymakers, staff, and healthcare workers; the prison policies must be revisited and adapted to deliver the right-based and evidence-based treatment for incarcerated persons with drug use.