Abstract

## Background Research shows that the prevalence of substance use disorders among the prison population is high globally. Although prisons are highly controlled environments, access to drugs and other substances in prison remains a major problem. Yet, previous research is focussed mainly on the Western context, with the studies generally reporting on lifetime prevalence without reference to whether the disorders are manifest even within the controlled environment.

## Aims To estimate the prevalence of substance use disorders evident while in prison in Ghana and associated risk indicators. For these purposes, substance use disorder was defined by any indication of dependency, or escalating use or socially problematic use during the 12 months of imprisonment prior to the interview.

## Methods The study involved 500 adults (443 men and 57 women) in a medium-security prison in Ghana who had served at least 1 year of a prison sentence. Participants' alcohol use disorder was assessed separately from other substance use disorders which included cannabis, cocaine and other stimulants using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI); it is a structured interview and diagnostic tool for major psychiatric and substance use disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-10.

## Results Two percent of the 500 participants had used alcohol to the level of alcohol use disorder, and 6% had other substance use disorders in 12 months prior to interview and while in prison. Cannabis (4%) and stimulants (3%) were the most frequently reported substance use disorders. Logistic regression model estimates indicate that younger age, prior offending and alcohol use dependence were significantly associated with such disorders in prison.

## Conclusion In spite of efforts to prevent substance use in prison, nearly one in 10 of these prisoners were using alcohol or illicit drugs to a level indicative of substance use disorders. Our findings suggest that prioritising brief assessment may help identify those in most need of clinical help to limit their alcohol and illicit substance use problems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research shows that people with substance use disorders are overrepresented in prison (Fazel et al., 2006; UNODC, 2019; Winter et al., 2016), and almost half of new prison entrants have an alcohol use disorder (Fazel et al., 2017). It is also recognised that convicted prisoners with substance use disorders are more likely than convicted prisoners without such disorders to be young, using heroin or crack cocaine or other substances daily in the 6 months before incarceration, intoxicated while committing a crime, or using substances to relieve insomnia, boredom or as a coping mechanism (Bukten et al., 2020; Kolind, 2015; Rowell-Cunsolo et al., 2016).

The general paucity of data on the prevalence of substance use disorders in Ghana prevents an accurate assessment of this problem in the general population, and little is known about substance use disorders in prisons in Ghana (Bird, 2019). One study reported that over two-thirds of prisoners had abused substances, with cannabis being the most commonly used substance (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2020). Another prison study in Ghana reported that substance users are youthful, poor, unemployed and previously incarcerated with substance-related offences (Omane-Addo & Ackah, 2021). Reasons cited for drug use were boredom, stress and boosting appetite (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2020). Similar reasons, such as boredom, coping mechanisms, depression, harsh prison conditions and lack of meaningful activities, addiction, peer pressure and overcrowding have been found in other studies (Boakye et al., 2022; Rowell-Cunsolo et al., 2016; Skowroński & Talik, 2018). Parimah et al. (2020) found that prisoners convicted of possessing cannabis for personal use for the first time were likely to have used substances within the past 30 days; about a third had used cannabis and nearly one fifth had used other drugs. The authors further reported an association between recidivism and other substance use. Reoffending rates have been reported to be higher among people who were substance-involved than those who were not (Bennett et al., 2008). These studies, however, focussed on substance use rather than substance use disorders.

It is generally more difficult to access illicit substances inside prison than outside, and for many substance users in custody, incarceration results in their stopping the use of substances or using them less frequently (Carpentier et al., 2018). Yet, there is evidence that some incarcerated persons continue to access their preferred substances in prison and are likely to experiment with new ones (Carpentier et al., 2018; Rowell-Cunsolo et al., 2016). It is possible that, in spite of searches, new prison entrants may bring prohibited substances to prison (George et al., 2009; Trestman & Wall, 2018), but access to substances in prison is probably more likely through contact visits, mail, court trips, inadequate searches, use of drones, tennis balls or staff involvement (Ferrigno, 2015; Global Prison Trends, 2015; Payne, 2006; Trestman & Wall, 2018). Prisoners who are considered high-ranking in the prison community have power and usually are in gangs and in control of the drug trade in prisons (Trestman & Wall, 2018). Drugs or trafficking activities may be bartered for valuable commodities and/or to pay drug debts (Trestman & Wall, 2018).

By contrast, being in prison for some is an opportunity to address some of the complex health and social problems, including alcohol or other substance use problems or disorders, because of access to rehabilitation and other health-related programmes/interventions which otherwise are usually not accessible to these people (Carpentier et al., 2018; Snow & Levy, 2018). To effect and mandate such therapeutic outcomes, alternative pathways to imprisonment have been developed to deal with incarcerated persons with substance and alcohol problems. These may include Drug Court-mandated supervised treatment programmes and later community supervision under court orders that provides a safe management structure for the substance problems, especially when offence-related, together with reintegration into the community; this approach has been shown to reduce recidivism (Global Prison Trends, 2015), but still many slip through this net and may even be harder to manage and treat.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of substance use disorders despite being resident in a medium-security prison. Substance use disorders here refer to dependence on illicit drugs and substances such as cannabis, heroin, cocaine, amphetamines and other stimulants. The study also examined alcohol use disorder and other major psychiatric disorders as risk indicators of substance use disorders. It is the first major study that examines the prevalence of substance use disorders (i.e., dependence on illicit drugs) while serving a sentence in a Ghanaian prison and the factors associated with these disorders.

2 METHODS

2.1 Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) Committee on Human Research, Publications and Ethics Committee (CHRPE/AP/190/18).

2.2 Study setting

The study was conducted in the only medium-security prison in Ghana. The prison was established in 1960 and holds over 3000 men and women in the facility which is well above its capacity of 717 (Ghana Prisons Service, 2013). At the time of the study, there were 3250 people held in the facility. The prisoners are from various parts of the country and usually serving sentences for serious indictable offences such as murder, sexual assaults, major violent crimes, economic crimes and drug-related offences, including human trafficking. The history and reach of the prison make it a very important facility in the prison system of Ghana.

2.3 Participants

The sample of 500 (443 men and 57 women) represents 15% of the 3,250 people held in the prison at the time. The inclusion criteria for the study were that participants should have been sentenced and have been incarcerated for at least 12 months. An announcement of a mental well-being survey, inclusive of alcohol and/or other substance use, was made by the prison officers at the prison yards daily for a week before the data collection commenced. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study. Persons who expressed interest completed the participant consent form prior to taking part in the study.

2.4 Measures

Sociodemographic data, including age, sex, occupation, marital status and religion, were recorded. The study also recorded details of prison status, duration of stay in prison and type of offence(s) committed. In assessing prior offending, offenders were asked whether it was their first time in prison or if they had been previously incarcerated and if yes, how many times. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, Version 6) was used as the structured diagnostic screen for the presence or absence of mental health problems. This instrument has been used to examine the patterns of mental disorders in other prison populations with characteristics similar to the sample in the selected prison for the present study (Naidoo & Mkize, 2012). The MINI instrument was designed as a brief structured diagnostic interview for the major psychiatric disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and DSM-5 and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (Lecrubier et al., 1997). The MINI instrument assesses alcohol use disorder separately from other substance use disorders which comprised illicit drugs such as cannabis, heroin, cocaine and other stimulants. Studies on validity and reliability show that it has high reliability and validity (Amorim et al., 1998). All questions are scored by circling either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The study used varied timeframes to measure mental disorders. The timeframe for major depression was 2 weeks, for generalised anxiety disorder it was 6 months (Sheehan et al., 1998) and for any substance disorder it was 12 months.

2.5 Procedure

Data collection occurred in the multipurpose yard in the prison. The interviews were conducted by the first (GD) and second author (WAD) and assisted by trained research assistants with a background in psychology. Prison staff were constantly present, but at a distance from where the interviews took place; this ensured the safety of the participants and the researchers while allowing the interviews to be confidential.

Participants were informed about the aim of the study. Participation in the research was voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any point during the research without consequences and of the confidentiality of the information being obtained from them. Limitations on confidentiality, such as the researchers' obligation to report an intention to self-harm or cause harm to others, were discussed with participants. Participants were assured that their responses would not be linked to their prison records and that the information gathered would be used solely for the research and subsequent publication. They were also informed that participation in the research would have no bearing on their incarceration status except in the most general terms, perhaps providing valuable insights into the subject of the research. Verbal and written consent were obtained from participants prior to completing the questionnaire and the MINI screening instrument.

All the researchers were proficient in at least two other local languages besides English. For participants who did not speak English fluently, the questions were translated into their local languages (e.g., ‘Twi’, ‘Ewe’ and ‘Ga’). To ensure accuracy in the responses the researchers administered and completed the questionnaires with the responses provided by all participants. Participants were compensated for their time by providing them with toiletries for participation at the end of the entire data collection process. This was to ensure participation was voluntary. Each interview lasted approximately 20–25 min.

2.6 Analytic strategy

We analysed the data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 28 (SPSS, 2021). We checked the data for consistency, outliers and missing values. We first estimated the prevalence of alcohol use disorder and other substance use disorders (illicit drugs) separately among the sample. The variables were dichotomised, and the odds ratio (OR) was employed to measure the strength of the relationship between the outcome (illicit drugs) and the risk indicator variables based on 95% confidence interval (CI). The logistic regression model was then used to estimate the association between the risk indicators and substance use disorders (i.e., dependence on illicit drugs).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic characteristics

The age range of the sample was between 20 and 60 years, with a mean age of 30.01 years (SD = 13.87). The largest group (n = 244, 49%) was aged between 31 and 50 years. Most of the participants were married (n = 274, 55%); the rest were either divorced (n = 19, 4%) or single (n = 178, 36%). About half (n = 263, 52%) had lower-level education, while 7% (n = 36) had tertiary education. Almost all (n = 482, 97%) had been convicted and sentenced to prison for the first time. They were serving sentences variously for theft (n = 63, 13%), robbery (n = 101, 20%), murder (n = 105, 21%), defilement (n = 97, 19%), possession of narcotics (n = 56, 11%), rape (n = 4, 1%) or other serious offences (n = 78, 16%).

3.2 Prevalence of substance use disorders

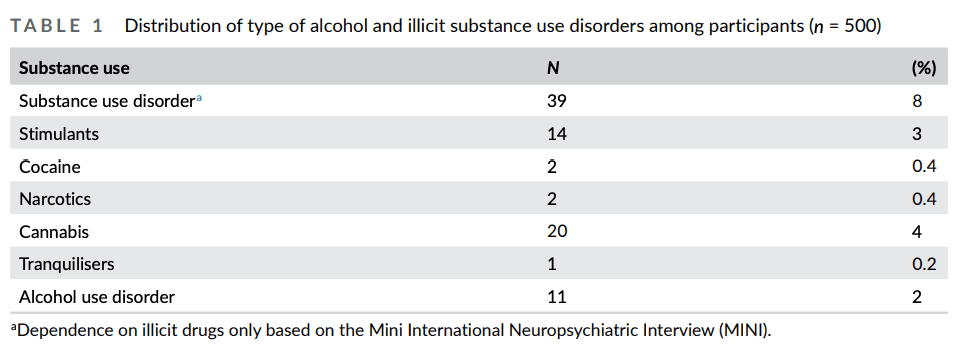

Table 1 shows the patterns of substance use disorders in the sample. Despite being in prison, 8% of the participants had used alcohol or illicit substances (e.g., cannabis, cocaine) in prisons during the 12 months prior to interview to a level consistent with substance use disorder. Broken down by licit and illicit substances, only 2% of the 500 participants reported alcohol use/or dependence at the time of the interview, while 4% and 3% reported cannabis stimulant use, respectively, at some time during the year in prison.

TABLE 1. Distribution of type of alcohol and illicit substance use disorders among participants (n = 500)

3.3 Risk indicators of substance use disorders in prison

We estimated two logistic regression models. Model I estimated the relationship between sociodemographic variables and substance use disorders (i.e., dependence on illicit drugs or alcohol use disorder). Major psychiatric disorders were included in to estimate their relationship with substance use disorders.

Table 2 shows that none of the psychiatric disorder indicators was significantly related with substance use disorder. Of the sociodemographic factors, only age (31–50 years) had a statistically significant association with substance use disorder (OR = 12.91, 95% CI [1.70–98.06]). That is those aged between 31 and 50 years are 12.91 times more likely compared with those who are 30 years and below of being dependent on illicit substance. Alcohol use disorder (OR = 15.46, 95% CI [4.08–58.57]) was associated with substance use disorder. Prisoners with a prior offence history had over three times the odds compared with those with no prior offence history of having a substance use disorder (OR = 3.66, 95% CI [1.07–12.47]).

TABLE 2. Logistic regression results showing the odds of sociodemographic characteristics and major psychiatric conditions relating to substance use disorders

ABLE 2. Logistic regression results showing the odds of sociodemographic characteristics and major psychiatric conditions relating to substance use disorders4 DISCUSSION

Our findings show that the prevalence of substance use disorders among those serving a sentence in the only medium-security prison in Ghana is about 10%, despite adequate staffing and a rather high level of security. All the previous studies in Ghana reporting a high prevalence rate of substance use were conducted in a camp prison or central prison, which are known to have inadequate staffing levels and are relatively low-security facilities (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2020; Omane-Addo & Ackah, 2021; Parimah et al., 2021). Although this prevalence figure is low compared with most reports on prisoners internationally, others have used a different approach to measurement and are generally reporting lifetime prevalence. In our study, the MINI questionnaire was used to assess substance use disorder among the offenders which is a brief diagnostic instrument, hence providing structure and validity to the assessment unlike previous studies that used non-standardised self-reported questionnaires developed by the authors or used screening tools to assess substance use. Of most importance, the MINI questionnaire as used in our study measured the 12-month prevalence of substance use disorders while offenders were incarcerated, whereas the previous studies had no such time restrictions in estimating substance use. Boys et al. (2002), for example, reported similar prevalence for cocaine (9.3%) and cannabis use (6.4%) when they assessed substance use initiation whilst in prisons in England. Our findings also confirm evidence from previous studies in prisons in Ghana and the global literature suggesting that cannabis is the most commonly used substance in prison (Carpentier et al., 2018; Lukasiewicz et al., 2007; UNODC, 2019).

Consistent with previous studies, age, reincarceration and alcohol use disorder were significantly related to illicit drug use disorders. Both our study and a study in France using the MINI questionnaire found that younger–middle-aged people in prison (30–50 years) were more likely than older ones (above 50 years) to have substance use disorders in the last 12 months (Lukasiewicz et al., 2007). A national study in England reported similar but more nuanced results about age of substance use initiated in prison (Boys et al., 2002). This study found that although older people (40+) were less likely to initiate substance use in prison compared with younger people (16–20), those aged 21–29 were also significantly more likely than those aged 16–20 to initiate substance use. Compared with adults, young people are more likely to be daring and to engage in high-risk behaviours (Boakye, 2013). They are, therefore, more likely to experiment with hard drugs and substances compared with adults. Another reason may be that young people may find adjusting to the harsh prison conditions especially challenging and, therefore, more likely to use drugs as a coping mechanism compared with older people (Boys et al., 2002).

In the current study, offenders who had been in prison before were more likely to report having a substance use disorder. A study in the USA reported that prisoners who were diagnosed with substance use disorder had the highest rate of rearrest upon release than those with no substance use disorder or mental health problems (Zgoba et al., 2020). The findings suggest incarceration of persons with substance use disorders may not be an effective response to addressing their risk of (re)offending. A targeted court-supervised treatment for substance and/or alcohol use disorders could be more effective in addressing the risk of recidivism and (re)incarceration.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to use a large sample size to estimate the prevalence of substance use disorder evidence during imprisonment in Ghana. We used a standardised psychiatric diagnostics instrument to assess substance use and major psychiatric disorders. Although an effort was made to ensure participants' anonymity and confidentiality, it is possible that the presence of prison officers, even if at a safe distance, may have impacted on the low rate of substance use disorders recorded in this study and true figures may be higher. Until effective treatment models supplant more punitive approaches, the likelihood of underreporting would persist. Participants may be concerned about the implication of disclosing their dependence on prohibited substances in prison. In addition to the 12-month prevalence of substance use/dependence, it would have been useful to assess participants' substance use/dependence prior to their incarceration. It would be important to know the extent to which these men and women were merely being resourceful in maintaining their substance use disorders and the extent to which the prison environment was drawing in new cases.

5 CONCLUSION

We assessed the prevalence of substance use disorders in a medium-security prison in Ghana and found that about 10% of incarcerated persons were using alcohol or illicit drugs that put them over the threshold for a substance use disorder active while in prison. It is the first study to use a standardised tool that supports DSM/ICD classification to assess alcohol and/or substance use disorders evident and active while under imprisonment in Ghana. The findings suggest the need for a rigorous and comprehensive assessment of alcohol and/or substance use disorders in prisons to help prioritise interventions. As shown, younger people in prison are especially likely to have a substance use disorder, as are those who had prior prison experience. In Ghana specifically, it is hoped that the passage of the Narcotics Control Commission Bill will lead to investment and provision of drug and alcohol services in prisons to ensure that the appropriate support and effective intervention are available to all those in need of them. The new provisions will need robust research evaluation.