Abstract

## Purpose The purpose of the study is to establish prospective relationships among school mean levels of substance use, developmental risk and resilience factors, and school discipline.

## Methods We linked 2003–2014 data from the California Healthy Kids Survey and the Civil Rights Data Collection, from more than 4,800 schools and 4,950,000 students. With lagged multilevel linear models, we estimated relationships among standardized school average levels of six substance use measures; eight developmental risk and resilience factors; and the prevalence of total discipline, out-of-school discipline, and police-involved discipline.

## Results School mean substance use and risk/resilience factors predicted subsequent prevalence of discipline. For example, a one–standard deviation higher school mean level of smoking, binge drinking, and cannabis use was associated, respectively, with 16% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 14%, 18%), 18% (95% CI: 16%, 20%), and 21% (95% CI: 19%, 23%) higher subsequent prevalence of total discipline. A one–standard deviation higher mean level of community support and feeling safe in school was associated, respectively, with 21% (95% CI: 18%, 23%) and 9% (95% CI: 7%, 11%) lower total discipline. Higher violence/harassment was associated with 5% (95% CI: 4%, 7%) higher total discipline. Peer and home support, student resilience, and neighborhood safety were not associated with total discipline. Nearly all associations remained, attenuated, when we restricted to out-of-school and police-involved discipline.

## Conclusions Schools with students who, on average, have higher substance use, less school and community support, and feel less safe in schools have a higher prevalence of school discipline and police contact. The public health implications of mass criminalization extend beyond criminal legal system settings and into schools.

Implications and Contribution Using a data set linking student health and discipline measures, this study provides empirical evidence that schools' average levels of student substance use and developmental risk and resilience factors longitudinally predict school discipline and school-based police contact—outcomes that characterize the school-to-prison pipeline. |

Over the past decade, the intersections of public health and mass incarceration have reached the forefront of public health discourse. Researchers and practitioners now understand that social determinants of health disparities (namely racism and social class) are intertwined with exposure to mass incarceration. Less has been documented, however, about the public health implications of a closely related trend, the school-to-prison pipeline, which describes a set of policies and practices that make it more likely for some adolescents to be criminalized and ensnared in the legal system than to receive a quality education. These policies and practices include zero-tolerance disciplinary policies; airport-style security and surveillance; increased presence of police in schools; and increased use of school discipline (suspensions, expulsions, and police referrals/arrests) in response to student misbehavior. However, more broadly, the school-to-prison pipeline, understood as auxiliary to mass incarceration, is one articulation of an expanded carceral state. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate a public health implication for these trends. We establish, for the first time, longitudinal relationships among school average levels of adolescent substance use and other developmental risk and resilience factors and the prevalence of school discipline—an initiating component of the school-to-prison pipeline.

The expanding carceral state, the school-to-prison pipeline, and school discipline

As a metaphor, the school-to-prison pipeline is constitutive of the neoliberal transformation of the state in the late 20th century and the “organized abandonment” it entailed. Government withdrew from social provision and managed the consequences of that retrenchment (poverty, unemployment, civil unrest, disinvestment in public education and public health, and so forth) by investing in systems of criminalization, behavioral surveillance, and punishment. From the perspective of a critical sociology of punishment, civic institutions, like schools, transformed to internalize carceral logics. The function of schools to educate, cultivate, and meet the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional health and developmental needs of students was displaced to administer the carceral flow of a racialized, criminalized population.

As a set of policies and practices, the school-to-prison pipeline comprises direct and indirect pathways from schools to the criminal legal system. The direct pathway is through the growing presence of police in schools. A new phenomenon beginning in the 1990s, there are now at least 20,000 police officers employed in schools nationwide, a nearly 40% increase from 1997. The number of school-based arrests increased 300%–500% since the 1990s, resulting in hundreds of thousands of referrals to the legal system each year. The indirect pathway is through substantial increases in the use of suspension and expulsion to deal with misbehavior in schools. Out-of-school suspensions have more than doubled over the past 40 years, and students are more than twice as likely to be arrested in the month they are removed from school compared with months when they are not removed. These policies have been borne disproportionately by adolescents of color. Black students are more than three times likely to be suspended or expelled than white students, controlling for socioeconomic status and misbehavior. Indeed, racialized disparities in school discipline likely contribute to the overrepresentation of Black people in the criminal legal system.

The growth and development of these direct and indirect pathways from schools to the criminal legal system was fueled by racialized, manufactured fears of “juvenile superpredators” and the introduction of “zero tolerance” policies in schools in the 1980s. Zero-tolerance policies, mirroring the U.S.'s “tough on crime” approach to politics and governance, mandate the use of exclusionary discipline (i.e., suspension, expulsion), often regardless of the severity of or context surrounding an incident. By 1997, 75%–90% of schools in the U.S. had enacted zero-tolerance policies. However, although the potential health and developmental implications of this carceral turn in public education have been theorized, they have been understudied empirically in population data.

Hypothesized adolescent health predictors of school discipline

Most empirical research on determinants of school discipline focuses on the role of economic disadvantage, racial composition of schools/communities, racially discriminatory application of school disciplinary policies, and teacher training. These studies find, for example, that schools in districts with higher levels of economic disadvantage have higher school discipline and arrest rates than those with less economic disadvantage and that poorer students are at greater risk for school discipline than wealthier students. Racialized disparities in school discipline are worse for black students in more integrated schools, and the proportion of black students in schools is positively associated (and the proportion of white students negatively associated) with school discipline rates.

Despite this substantial evidence for sociodemographic determinants, there is little epidemiological research on how public-health–related factors may pattern the distribution and determinants of school discipline. However, theory and evidence from previously unconnected bodies of research provide strong reasons to expect that the social determinants of adolescent health and well-being are intertwined with the social determinants of the school discipline component of the school-to-prison pipeline. For example, adolescent externalizing problems (e.g., disruptiveness, aggression) are highly comorbid with internalizing problems (e.g., depression and anxiety), and both are associated with substance use, which is a prototypical zero-tolerance infraction for school discipline/arrest. Externalizing problems and substance use, in turn, are associated with school truancy and arrest. Community economic disadvantage and exposure to violence are associated with childhood and adolescent behavior problems and substance use.

Moreover, there are numerous structurally distributed and socially determined developmental risk and resilience factors that likely play a role in school discipline. For example, supportive parenting practices were associated with lower likelihood of adolescent substance use and suspensions among a small sample of eighth-grade students. Peer attitudes toward substance use and peer misbehavior are predictors of adolescent substance use and suspension. School- and community-level supports such as positive school climate, student sense of belonging, and community youth programs positively influence adolescent health and may mitigate the harmful effects of school discipline [37].

However, prior research on these factors, in addition to only partially examining unconnected components of hypothesized pathways, primarily involves small or single cross-sectional samples, includes only self-reported school discipline measures, and/or permits only between-student (rather than between-school) comparisons. The latter limitation is particularly relevant because school discipline's role in the school-to-prison pipeline is theorized as an institutional mechanism of structural racism and criminalization. If, inter-relatedly, the school-to-prison pipeline is also an institutional mechanism for responding to adolescent health and developmental needs, we would expect schools with greater such needs to have higher levels of school discipline.

Because testing this hypothesis requires studying an institutional (schools) rather than an individual (students) level of analysis, we needed a unique data structure in which (1) student substance use and developmental risk and resilience factors could be aggregated to the school level, (2) these school-level aggregates could be combined with multiple sources of data on school prevalence of discipline and school district covariates, and (3) the number of schools was sufficiently large enough to ensure adequate variation in the predictors and outcomes. To our knowledge, such a data structure did not exist. We therefore created one by linking multiple data sources to establish empirical relationships between the aforementioned factors and school discipline/school police contact. We hypothesize that schools' average levels of substance use, depressed feelings, and individual, peer, family, school, and community risk and resilience factors will be associated with the prevalence of school discipline/school police contact.

Method

Data

We linked 11 years of repeated cross-sectional data from California from three sources: school discipline prevalence data from the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC), adolescent health and well-being data from the statewide California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS), and demographic data on California school districts from the American Community Survey (ACS).

The CRDC is the singular national survey of public schools in the U.S., collecting data on education and civil rights issues, including school discipline. Before 2011, the CRDC was a stratified random, representative sample of all U.S. public schools. Thereafter, the CRDC surveyed all public schools (N = 97,172 nationally). Responses come from designated school officials and official records (response rate = 98%–100%). Most research using the CRDC describes the sociodemographic variables that are associated with school discipline in a specific school year.

The CHKS is the largest survey of its kind in the U.S.: approximately 85% of public school districts in California participate. Districts administer the CHKS to all fifth-, seventh-, ninth-, and 11th-grade students, who participate anonymously. The survey asks about students' behavior, experiences, and attitudes related to their school, health, and well-being. The sampling strategy and psychometric properties of CHKS measures have been described in depth elsewhere. Average student response rates are typically >70%. We used 11 consecutive waves (2003–2005 through 2013–2014) of the CHKS.

The ACS Education Tabulation is a custom tabulation of ACS data for the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) containing publicly available demographic data for U.S. school districts. The data files are updated annually and based on ACS five-year estimates.

The CRDC contains unique NCES school identifiers, which we matched to CHKS unique County-District-School codes, using tables provided by the NCES. We linked school district demographic data from the ACS by the NCES school identifier.

Measures

School discipline and police contact

We constructed three measures of school discipline from the CRDC: total discipline (our primary outcome of interest) and two components of total discipline: out-of-school discipline and police-involved discipline. We chose the latter two outcomes to take full advantage of the longitudinal structure of our data linkages and determine whether school policing is a distinct outcome.

Total school discipline 2009–2014

In 2009, the CRDC began collecting detailed information on school discipline. In addition to expulsions and out-of-school suspensions, schools reported total in-school suspensions and police-involved discipline (school-based arrests and police referrals). We divided the sum of in- and out-of-school suspensions, expulsions, and police-involved discipline by total enrollment to create a total discipline prevalence proportion.

Out-of-school discipline 2003–2014

Historically, the CRDC collected limited data on school discipline. Schools reported the total number of expulsions and out-of-school suspensions that occurred in the reporting period. We divided the sum of these totals by total enrollment to create out-of-school discipline prevalence proportions.

Police-involved discipline 2009–2014

Given the direct role that police play in criminalizing students, we were interested in whether police-involved discipline alone was predicted by adolescent health and well-being. We created prevalence proportions of school-based arrests and police referrals divided by total enrollment.

Adolescent substance use and developmental risk and resilience factors

Schools are the primary unit of analysis in this study; we calculated the school mean or proportion of student responses to each measure described in the following. To facilitate comparisons across measures, we then standardized those values (i.e., calculated Z-scores) across all schools for each survey year. In the following, we describe the raw items and measures before standardization. Table A1 presents item composition, scoring, means, and standard deviations for all measures.

Substance use and depressed feelings

The CHKS asks students how many times in the past 30 days they had at least one drink of alcohol, binge drank (defined as four drinks for girls and five drinks for boys per drinking occasion), used cannabis, smoked a cigarette, or used a variety of other drugs (smokeless tobacco, inhalants, cocaine, methamphetamines, or amphetamines, ecstasy, LSD, or other psychedelics, any other illegal drug). Alpha coefficients range from .90 to .98. Students were also asked how many times in the past 30 days they felt depressed.

Community, home, peer, and school social support and student resilience

Students were asked several questions, scored from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (very true), about their home, school, and community environments; their friends; and themselves. We took the school mean of student responses to the items from each domain to create school-level summary measures for community (8 items), home (8 items), peer (5 items), and school (9 items) social support and student resilience (12 items). Example items for community support include the following: “Outside of home and school there is an adult who really cares about me,” and “…who tells me when I do a good job.” Example items for home support include the following: “A parent or adult in my home is interested in my schoolwork” and “…talks to me about my problems.” Example items for peer support include the following: “A peer my age really cares about me” and “…helps when I'm having a hard time.” School support items include the following “At my school, there is a teacher or some adult who listens when I have something to say” and “…notices when I'm not there.” Student resilience items represent self-efficacy, self-awareness, empathy, and problem-solving. Items include “I can work out my problems” and “I feel bad when someone gets their feelings hurt.” Alpha coefficients for these items ranged from .79 to .96.

Violence/harassment and school safety

Students reported how much they agreed that they felt safe in their schools and neighborhoods, scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Finally, students were asked 18 questions about the number of times in the past 12 months they experienced violence and harassment in schools, scored from 0 (zero times) to 3 (four or more times) [47]. Example items include having been shoved, slapped, hit, or kicked; been afraid of being beaten up; been in a physical fight; and had mean rumors or lies spread about them.

Potential confounders

Given the role of racism and social class in the school-to-prison pipeline, we theorized that several school-level and school-district–level variables confound the prospective relationships among adolescent health, risk/resilience factors, and school discipline. These included the school percentage of Black students; school district median age and median income; and the percentages of school district residents who were unemployed, had a high school degree, and identified as Black.

Analysis

In a first set of unadjusted models, we fit multilevel linear models regressing each school discipline measure on each standardized health and well-being factor, lagged by one year. These models included random intercepts for school and controlled for year. In a second set of adjusted models, we added the confounding variables described previously, lagged by one year, to each model. Model coefficients for standardized predictor variables can be interpreted as the change in outcomes associated with a one–standard-deviation increase in the predictor. All analyses were conducted in R, version 3.6.

The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University and University of Texas at Austin.

Results

After linking to the CRDC for the years 2003–2014, the CHKS contained data from 4,840 schools and 4,950,633 students. The sample of student respondents attending these California schools was 30% White, 7.4% Black, 6.3% American Indian/Alaska Native, 10.6% Asian, 3.3% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 43% Latinx. The mean prevalence of out-of-school discipline, total school discipline, and police-involved discipline was 19%, 32%, and 2%, respectively (Table A2). Figures A1-A4 present the means or proportions of all measures over time.

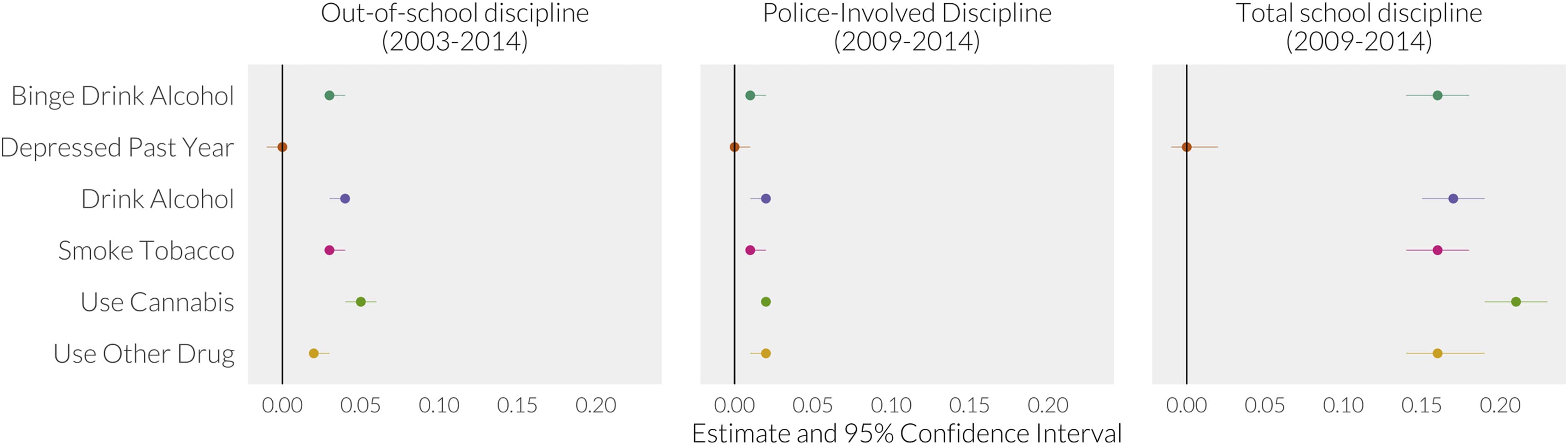

Figure 1 presents results from 18 adjusted multilevel linear models regressing the three school discipline measures on the six standardized, lagged school-level measures of substance use and depressed feelings. Table A3 presents unadjusted and adjusted coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each relationship. Higher school mean levels of binge drinking, drinking, and tobacco, cannabis, and other drug use were associated with higher school prevalence of discipline measures in the subsequent year, relative to schools with lower mean levels of substance use.

Figure 1. Results of 36 adjusted linear multilevel models regressing three school discipline measures on six lagged measures of substance use and depressed feelings.

Estimates for the associations between substance use and out-of-school discipline ranged from .02 (other drugs, 95% CI: .016, .03) to .05 (cannabis, 95% CI: .04, .06). That is, a one–standard-deviation higher school mean level of cannabis use was associated with a 5% higher prevalence of out-of-school discipline in the subsequent year. For total discipline, estimates ranged from .16 (smoked tobacco, 95% CI: .14, .18) to .21 (cannabis use, 95% CI: .19, .23). That is, a one–standard-deviation higher school mean level of tobacco use was associated with a 16% higher prevalence of total discipline in the subsequent year. For police-involved discipline, estimates for binge drinking and tobacco use were roughly .01 (95% CIs: .01, .02) after rounding and for cannabis, other drug, and alcohol use, approximately .02 with narrow CIs.

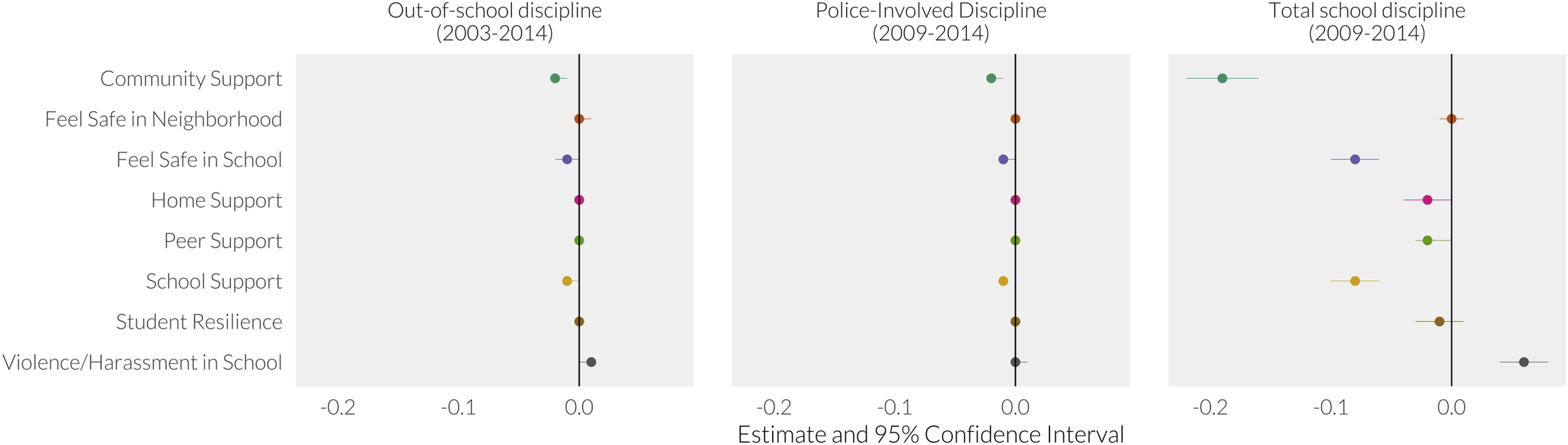

Figure 2 presents results from 24 adjusted multilevel linear models regressing the three measures of school discipline on the eight measures of risk and resilience factors. Table A4 presents unadjusted and adjusted coefficients and 95% CIs for each relationship. Schools with higher community and school support, and with more students reporting feeling safe in school, had lower prevalence of school discipline measures in the subsequent year. A higher school mean level of violence/harassment was associated with higher prevalence of school discipline measures in the subsequent year. Peer and home support, student resilience, and feeling safe in one's neighborhood were not associated with school discipline measures.

Figure 2. Results of 48 adjusted linear multilevel models regressing three measures of school discipline on eight lagged measures of risk and resilience.

For out-of-school discipline, estimates ranged from -.02 (community support, 95% CI: -.02, -.01) to .01 (violence/harassment in school, 95% CI: .0, .01). Estimates for total discipline were stronger, ranging from -.19 (community support, 95% CI: -.22, -.16) to .06 (violence/harassment, 95% CI: .04, .08). For example, a one–standard-deviation higher school mean level of community support was associated with a 19% lower prevalence of total discipline in the subsequent year. For police-involved discipline, estimates ranged from -.02 (community support, 95% CI: -.02, -.01) to -.01 (school support, 95% CI: -.01, -.01).

Discussion

In a longitudinal data set linking school mean health and discipline measures across the most populous U.S. state, we provide the first empirical evidence that schools' average levels of student substance use and developmental risk and resilience factors are predictors of school prevalence of suspensions, expulsions, and school-based police contact—outcomes that characterize the school-to-prison pipeline. Our findings are consistent with theory and evidence from previously unconnected bodies of research that the social determinants of adolescent health and well-being are intertwined with the social determinants of the school-to-prison pipeline. Findings suggest that at an institutional level, schools with students who—on average—engage in more substance use, have less school and community support, and feel less safe in school have a higher prevalence of school discipline and school-based police contact. Future research should confirm whether this institutional pathway also reflects an individual-level pathway, by linking student-level health and discipline data.

Our main findings are as follows: (1) Schools with higher average levels of substance use had between 16% and 21% higher prevalence of total discipline in the subsequent year than schools with lower levels of substance use; (2) Schools with higher average levels of violence and harassment had 5% higher prevalence of subsequent total discipline than schools with lower levels of violence and harassment, and schools in which students reported higher average levels of feeling safe in school, school support, and community support had 9%–21% lower prevalence of total discipline. Nearly all associations remained, attenuated, when we restricted to out-of-school and police-involved discipline.

These findings are not surprising. However, the persistence and pervasiveness of the school-to-prison pipeline, and the school discipline practices that constitute it, suggest that it remains essential to provide social movements, policymakers, parents, teachers, and students with empirical evidence that challenges the assumption that these practices work as intended and without collateral consequences. These policies and practices may in fact criminalize and punish students with health and developmental needs.

It is likely that students exposed to material and psychosocial deprivations conducive to substance use and mental health problems are more likely to get into trouble at schools. It is also likely that they attend schools that rely on suspensions, expulsions, and police (rather than counselors, social-emotional learning specialists, or social workers) to manage the consequences of those very same material and psychosocial conditions. At the school and community levels, investments in school policing, school securitization, and criminalization likely come at a cost of disinvestment in school and community supports and services that could mitigate the root causes of disciplinary issues. For example, in New York City schools, there are twice as many police officers as social workers and psychologists combined and nearly twice as many police as school counselors. Indeed, in the present study, school and community support and feeling safe in school were negatively associated with school discipline and police contact, but home and peer support and student resilience were not associated with school discipline and police contact. This may suggest that the appropriate targets for intervention are community and school contexts, rather than peer or parent individual-level factors.

It is also likely that exposure to high levels of suspension, expulsion, and police contact in schools creates or exacerbates material and psychosocial conditions conducive to adolescent substance use, mental health problems, and worse developmental risk and resilience. For example, the American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force found that zero-tolerance policies, which result in school discipline/police contact, are developmentally inappropriate for adolescents and may “create, enhance, or accelerate negative mental health outcomes by increasing alienation, anxiety, rejection, and breaking of healthy adult bonds”. We plan to explore the potential for such reciprocal relationships in future research.

The purpose of the present study was to empirically establish school mean levels of adolescent substance use, depressed feelings, and developmental risk and resilience factors as independent predictors of a key component of the school-to-prison pipeline—school discipline and police contact. However, this is undoubtedly not the full story. Substantial empirical evidence and gray literature find flagrant racialized disparities in the school-to-prison pipeline, suggesting that the associations identified in the present study are also likely racialized. We plan to determine, in future research, the extent to which that is the case and whether the racialized criminalization of both substance use and the consequences of community and school disinvestment help explain these documented disparities.

Our findings should be interpreted considering several limitations. First, by aggregating to the school level, discipline prevalence proportions may reflect multiple suspensions, expulsions, or police contacts for the same student. However, we do not believe that the presence of such students in a school would systematically bias other students' responses to the CHKS. Second, the CRDC did not require data reporting on school discipline for years before 2013–2014, and roughly 15% of California schools did not participate in the CHKS, which may result in informative missingness for some schools (if their failure to report or participate was related to high rates of the outcome or predictors) and random missingness for other schools (if they chose not to report or participate due to unfamiliarity with survey procedures). Third, the CRDC does not contain information on the reasons for reported school discipline, specific discipline infractions, or the severity of the actual behaviors that triggered disciplinary measures. Fourth, the CHKS is a school-based sample and thus does not include adolescents who were not attending school; therefore, students who had already been suspended, expelled, or incarcerated are underrepresented, likely resulting in more conservative estimates for associations with substance use, depressed feelings, and risk and resilience factors reported herein. Fifth, we examined a large number of associations in this analysis, which increases the probability of finding some to be statistically significant even if the association is due to chance. However, given that we only tested strongly theorized relationships, we do not believe that the universal null hypothesis and thus adjustments for multiple comparisons were warranted. Finally, data from the CHKS are self-reported.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the school-to-prison pipeline is intertwined with adolescent health and well-being. As a field now engaged in the study of mass incarceration and its collateral consequences, public health should extend its gaze beyond the walls of jails and prisons and into other institutions, particularly schools, where disinvestments in social and public health infrastructures are implicated in the processes of criminalization that contribute to an expanding carceral state.