Abstract

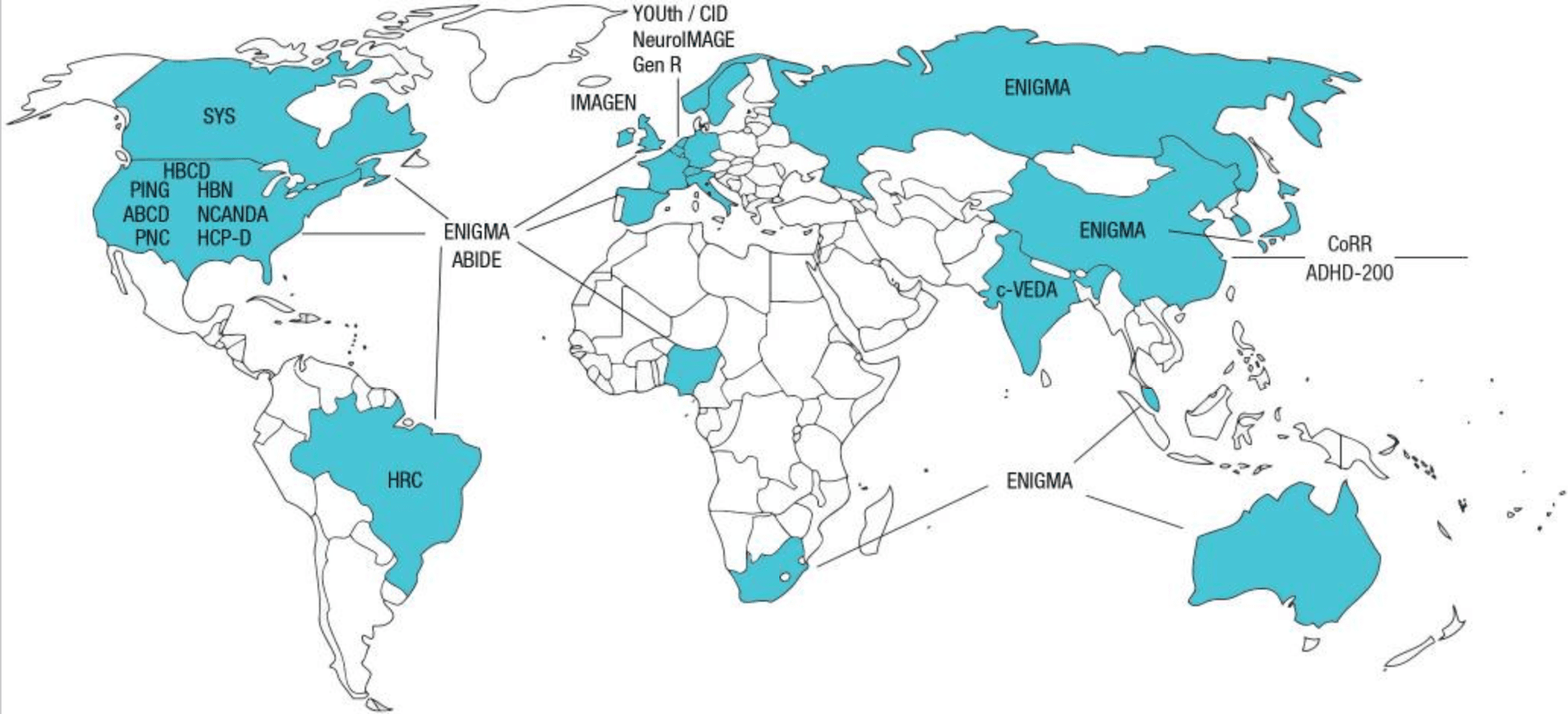

The number and size of open-access developmental data sets that include brain and behavioral information have dramatically increased in recent years (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). These collaborative initiatives represent a new era of science that democratizes data access, facilitates scientific discovery, boosts statistical power, enhances reproducibility and replication, and can inform policy (Rosenberg et al., 2018). However, to use these data responsibly, we must consider the broader social context, the dynamic and interactive process of development, and the strength and limitations of the data when formulating our research questions, designing statistical models, and interpreting our findings. Here, we use the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the largest longitudinal study of brain development and youth health in the United States to date, to suggest best practices for responsible data use. To be developmentally informed and responsible users of these data, we must consider (a) the heterogeneity of experiences within the broader social context in which development occurs and (b) the potential for adaptation to the environment and developmental change.

Introduction

The number and size of open-access developmental data sets that include brain and behavioral information have dramatically increased in recent years (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). These collaborative initiatives represent a new era of science that democratizes data access, facilitates scientific discovery, boosts statistical power, enhances reproducibility and replication, and can inform policy (Rosenberg et al., 2018). However, to use these data responsibly, we must consider the broader social context, the dynamic and interactive process of development, and the strength and limitations of the data when formulating our research questions, designing statistical models, and interpreting our findings. Here, we use the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, the largest longitudinal study of brain development and youth health in the United States to date, to suggest best practices for responsible data use.

Existing, ongoing, or planned data sets including structural and functional neuroimaging data from approximately 500 or more children or adolescents. These data sets, which represent both prospective and retrospective samples, are the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study (ABCD; United States); Healthy Brain Network (HBN; United States); Lifespan Human Connectome Project Development (HCP-D; United States); National Consortium on Alcohol and Neurodevelopment in Adolescence (NCANDA; United States); Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition, and Genetics (PING; United States); Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC; United States); Saguenay Youth Study (SYS; Canada); High Risk Cohort Study for the Development of Childhood Psychiatric Disorders (HRC; Brazil); Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE; United States, Germany, Ireland, Belgium, The Netherlands); Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta Analysis (ENIGMA; worldwide); IMAGEN (England, Ireland, France, Germany); Youth of Utrecht (YOUth; part of the Consortium on Individual Development, or CID; The Netherlands); Generation R (Gen R) Study (The Netherlands); NeuroIMAGE (follow-up of the Dutch arm of the International Multi-Centre ADHD Genetics, or IMAGE, project; The Netherlands); Consortium on Vulnerability to Externalizing Disorders and Addictions (c-VEDA; United Kingdom, India); Consortium for Reliability and Reproducibility (CoRR; China, United States, Canada, Germany); ADHD-200 (United States, China); and HEALthy Brain and Child Development Study (HBCD; United States). Although samples are distributed across the globe, African, Middle Eastern, South Asian, Oceanian, and Central and South American populations are underrepresented. Data-collection efforts in these regions and others will be important for ensuring diverse, representative samples that will allow researchers to uncover general principles of the developing brain. (The map outline is courtesy of Wikimedia user Loadfile and is edited with permission from Rosenberg et al., 2018.) |

To be developmentally informed and responsible users of these data, we must consider (a) the heterogeneity of experiences within the broader social context in which development occurs and (b) the potential for adaptation to the environment and developmental change.

Consider the Broader Social Context in Which Development Occurs

The ABCD Study focuses on a cohort of nearly 12,000 participants who were 9 to 10 years old at baseline and are currently being followed for 10 years. Youths and their families provide rich details about their environmental experiences and undergo extensive phenotypic, cognitive, genetic, emotional, health, and neuroimaging assessments. These data provide an unprecedented opportunity to advance our understanding of how the culmination of different experiences interact with changing biology across development. Yet the ABCD Study does not capture the full spectrum of experiences or environments that may influence a youth’s development (e.g., structural inequality). Moreover, the sample is not representative of the U.S. population on sex, race, ethnicity, education, and household income (Compton et al., 2019; Dick et al., 2021; Garavan et al., 2018), which can limit the ability to generalize findings across and between youths from diverse groups (cf. Heeringa & Berglund, 2020). Therefore, it is important to consider measured and unmeasured meso-level factors (e.g., neighborhood influences) and macro-level factors (e.g., systemic or structural factors) when examining developmental trajectories or outcomes, particularly with open-access developmental data sets that may be used by scientists from many disciplines.

Development does not occur in a vacuum and is influenced by complex multifaceted processes. Youths live in multiple social contexts (e.g., family, neighborhood, region) and hold multiple identities (e.g., racial, cultural, gender). Therefore, studies that focus on single environmental factors (e.g., median neighborhood income) fail to capture the considerable heterogeneity in youths’ experiences and environments (Cohodes et al., 2021; Finkelhor et al., 2007) and their contributions to development (Foulkes & Blakemore, 2018; Hong et al., 2021). Large, publicly accessible data sets such as the ABCD Study include a wealth of assessments capturing different aspects of youths’ experiences (e.g., culture and environments) that may relate to developmental outcomes (Barch et al., 2018; Hoffman et al., 2019; Zucker et al., 2018). In addition to acknowledging that no measures will fully capture the relevant environment or experiences, we should consider utilizing multifactorial or multiple separate variables to estimate context and experience to enhance accuracy in measurement and interpretation. Further, we should avoid using any single variable (e.g., race, which is a social construct; Trent et al., 2019) as a proxy for other sociodemographic issues (e.g., marginalization) and avoid overly simplistic conclusions when examining development.

Structural and cultural racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression and inequity shape youths’ day-to-day experiences and influence their development (Neblett, 2019; Syed et al., 2018). Although the ABCD data include some self- and parent-report assessments of youths’ exposure to different forms of inequality (e.g., discrimination, resource insecurity, neighborhood disadvantage), many of the manifestations of structural inequality, privilege, and power are not measured (Cole, 2009; del Río-González et al., 2021). It is therefore important to situate our research in the broader social context and exercise caution when making claims about developmental findings. We should be careful to acknowledge unmeasured factors that may influence our findings given that not all critical factors are measured.

Consider the Potential for Adaptation to the Environment and Developmental Change

Development is a dynamic, interactive process in which a youth’s changing biology adapts to environmental challenges encountered in various developmental stages and contexts (Gottlieb, 1991; Greenough et al., 1987; Karmiloff-Smith, 2009). When there is a deviation in the expected environment (e.g., absence of primary caregivers, childhood maltreatment, institutionalized care), some evolutionarily conserved mechanisms may be maladaptive for that current environment (Casey et al., 2010). Thus, outcomes that could be interpreted as unfavorable in one environment may actually reflect an adaptive process suited to meet the demands of another environment (Amso, 2020). It is therefore important to acknowledge that a given outcome may be favorable or unfavorable depending on the individual’s current and/or past environment.

Moreover, how youths respond to the same environment or experience can be quite different. For example, although some early life experiences (e.g., physical abuse, exposure to community violence) can increase risk for psychopathology, many children who experience adversity do not develop mental health or behavioral problems (Kessler et al., 2010; Masten, 2001). The heterogeneity in outcomes following certain early life experiences highlights the limits in using variables within only one level of analysis (e.g., environment, genetics) as predictive criteria. Recent advances in predictive modeling underscore the need to utilize variables across multiple levels simultaneously so as to capture the youth more holistically (Rosenberg et al., 2018). However, even when multilevel approaches are used, accuracy of prediction is low across developmental periods (e.g., using childhood experiences to predict adult behavior; Salganik et al., 2020). Therefore, we should be cautious when using predictive modeling. Furthermore, given the limitations of predictions across developmental stages, we must recognize the potential real-life implications of making such predictions (e.g., stigmatization that results in the narrowing of opportunities).

Youths are constantly adapting, and change remains possible. Research shows that the brain is plastic throughout life, with heightened potential for change during sensitive periods (Bavelier et al., 2010; Fu & Zuo, 2011). Ample time in a different environment can have profound effects on outcomes (Chetty et al., 2016). And interventions can mitigate the effects of early-life experiences (Gee & Casey, 2015). Thus, deterministic claims should not be made on the basis of a single time point using cross-sectional observational data or on the basis of multiple time points within a circumscribed developmental period. Moreover, we should be modest with our conclusions about development and avoid deterministic language in our interpretation and communication of findings (e.g., “incorrigible youth,” “diminished” ability for change).

Best Practices for Responsible Use of Open-Access Developmental Data

Given our own knowledge of the data and of the rich array of factors that influence development, some of which may be unmeasured, we must approach our science with humility. We suggest the following best practices for responsible use of open-access developmental data:

Respect the youths and families whose lives form the basis of the research data.

Consider whether we and/or members of our research teams have the knowledge needed to thoughtfully and thoroughly address questions regarding the influence of social context on developmental outcomes.

Practice awareness and appreciation for the heterogeneity of youths’ experiences and environments when formulating developmental research questions and analyses.

Utilize multifactorial or multiple separate variables to estimate context and experience to enhance accuracy in measurement and interpretation.

Situate findings in the broader social context by noting that some important factors may not always be measured.

Avoid using causal or deterministic language, either explicit or implicit, based on a single time point using cross-sectional observational data or based on multiple time points within a circumscribed developmental period.

Be modest with conclusions regarding observed associations even when using large developmental data sets, given all youths’ potential for change.

Recognize that outcomes that may be viewed as unfavorable in one environment may actually reflect an adaptation in another environment.

Consider how our findings may be misinterpreted as deterministic, to the detriment of other groups or individuals.

Conclusion

With big data comes big responsibility. Large, open-access, longitudinal data sets with deep phenotyping (e.g., ABCD Study) provide the opportunity to conduct multifaceted research. However, we must consider the strengths and limitations of these data, be mindful of how we include data in statistical analyses, and be cautious about how we interpret the results of these statistical analyses even when they are conducted rigorously. This Data Brief underscores the importance of considering the heterogeneity of youths’ experiences within the broader social context in which development occurs. Development is a multifaceted and dynamic process, and researchers must also consider the potential for adaptation and change among all youths. These considerations may enhance accuracy in the use and interpretation of open-access developmental data and mitigate potentially harmful narratives. We as scientists have an opportunity and an obligation to use these data to inform policy and to promote positive change in academic, health, and social outcomes for all youths.