Abstract

Due to historical and current systemic racial inequities, African American adolescents and emerging adults living in low-income urban communities bear the burden of higher rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and exposure to community violence. Both exposure to ACEs and community violence are linked to higher levels of substance use. However, limited research exists on how exposure to community violence exacerbates the association between ACEs and higher frequencies of substance use in adolescence and emerging adulthood. There is also a need to understand how community-level protective factors may weaken the relations between ACEs and higher rates of substance use. The current study focuses on two separate samples of primarily African American adolescents (n = 378; ages 12-17) and emerging adults (n = 218; ages 18-22) living in low-income urban areas in the southeastern United States. This study contributed to the literature by using hierarchical regression analyses to examine: (a) the association between ACEs and the frequency of substance use, and (b) the moderating effects of exposure to community violence and community recognition and community support on relations between ACEs and frequency of substance use.

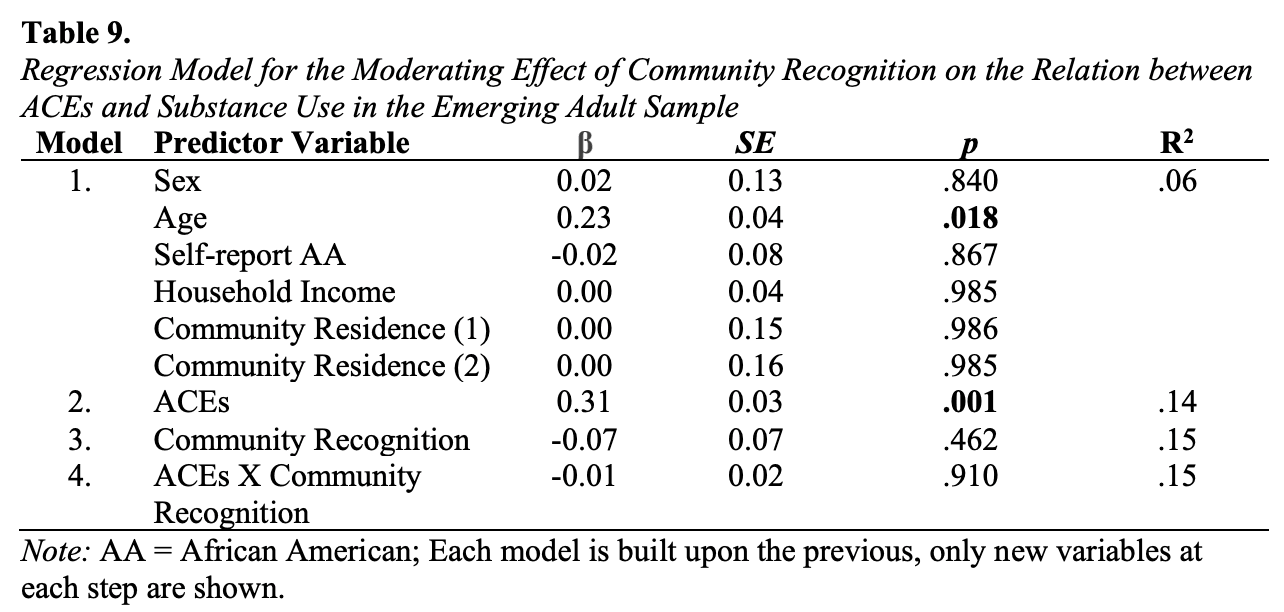

Literature Review

In the present study, I explored the extent to which community vulnerability (i.e., the burden of exposure to community violence) and community protective factors (i.e., community support and community recognition) moderate relations between ACEs and the frequency of substance use. My study focuses on two primarily African American samples of adolescents and emerging adults, respectively, living in low-income urban areas. The literature review begins with a brief description of the developmental stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood and the need to understand better how experiencing ACEs is related to substance use during these developmental timeframes. An overview of ACEs is then provided, including their prevalence in adolescence and emerging adulthood, association with socio-emotional and behavioral health, and how ACEs impact African Americans living in low-income urban areas. The next section explains the theoretical approaches to show how ACEs and substance use might be associated and the rationale for the potential moderating role of community violence exposure, community support, and community recognition. The current study draws from the Phenomenological Variant of Ecological System Theory (Spencer, 1997), the Social-Ecological Model (CDC, 2002), and the Ecological-Transactional Perspective (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006). The last section, it focuses on the importance of testing vulnerability and protective factors that may moderate relations between the experience of ACEs and substance use among adolescents and emerging adults is discussed with a focus on the potential role of community factors. Specifically, the potential role of exposure to community violence as a vulnerability factor and community support and community recognition as protective factors is described.

Emerging Adulthood and Adolescence

Adolescence is a critical developmental period of transitioning in various ways; socially, mentally, and physiologically. Transitions during adolescence also reflect the process of development in context in schools (e.g., middle to high school and high school to college transitions), within social networks (e.g., peer, family, and community networks), and in assuming new roles in work and living situations (Lerner & Castellino, 2002). During this period, adolescents start to expand their interest in different ways, for example through positive youth development opportunities and supportive relationships with peers and adults. However, adolescence is also a developmental period with an increased likelihood of risk-taking behaviors (e.g., substance use) (Boyer, 2006). The negative consequences associated with engaging in risktaking behaviors highlight the importance of identifying risk, vulnerability, and protective factors associated with these outcomes. The current study assesses the extent to which ACEs may be related to higher odds of engaging in substance use during adolescence.

Emerging adulthood is a period defined by neither adolescence nor young adulthood: it is the developmental period between those two that focuses on individuals ages 18-25 (Arnett, 2000). In adolescence, a majority of youth live at home, very few have children, and most are not married (Arnett, 2000). In contrast, for emerging adults, several different, home, school, and/or work contexts may be represented. Emerging adulthood is a period of a wide scope of possible activities (e.g., college/ higher education, work, and parenting) (Arnett, 2000). For example, by age 30, new norms are established with most emerging adults being parents and having a partner (U.S. Bureau of Census, 1997). The paths that emerging adults may follow are hard to classify due to the broad scope of tasks and life events occurring within this period. Thus, it is difficult to compare the experiences of emerging adulthood to other developmental stages. However, research shows that several risk behaviors peak during emerging adulthood including unprotected sexual activity and substance use (Claxton & Manfred, 2013; Schulenberg et al., 2001). The rise and peak in risk-taking behaviors in emerging adulthood may be due to individuals having more freedom and fewer constraints. Studying emerging adulthood in relation to ACEs is important to understand whether experiences of maltreatment and household dysfunction in childhood are related to higher rates of substance use during this developmental stage. Individuals in this age group may have stronger memories of and impacts associated with ACEs as compared to older adults because they are right over the threshold of adolescence.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

ACEs are defined as exposure to stressful and/or traumatic experiences that include household dysfunction, maltreatment, and other stressors occurring in children younger than 18 years of age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Typically, the total number of ACEs that youth experience up to the age of 18 is assessed to determine how cumulative experiences of childhood maltreatment and household dysfunction affect their socio-emotional and behavioral health. ACEs are categorized into three specific groups of experiences (i.e., abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction). Abuse includes experiences of physical or sexual abuse (i.e., being grabbed, slapped, pushed, and coerced into performing sexual acts). Neglect includes experiences of being abandoned and/or mistreated. Household dysfunction focuses on parental issues (i.e., divorce, domestic violence, and parent substance use disorders). ACEs can be traumatic and have negative lasting effects on children and adolescents including psychological and physical difficulties, risk-taking behaviors (e.g., substance use), and increased need for healthcare utilization (Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015). Considering the physiological and developmental ramifications, the experiences of ACEs may lead to the disruption of hormonal output and disrupt brain circuits and overall brain development (Short & Baram, 2019, Malave et al., 2022).

The occurrence of ACEs has been frequently reported among adult populations in the United States, and a number of studies linked the experience of ACEs to negative social, emotional, and behavioral consequences (e.g., Felitti et al., 1998; Pace et al., 2022). Studies assessing outcomes related to ACEs mainly focus on adult populations and include individuals across a broad age range. First examined by Felitti and their colleagues (1998), researchers identified positive relations between the total number of childhood ACEs occurring across the three categories (i.e., abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction) and adult health risk behaviors and chronic conditions (e.g., alcoholism and chronic depression). For example, in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) -funded Kaiser study (1995-1997), over 17,737 adults (ages 19 to 60 and above), a total of 13% of respondents experienced four or more ACEs, and 64% of the respondents experienced at least one ACE (CDC, 2021). In a separate study, a total of 214,157 adults (ages 18 to 65 and over) completed an annual survey between 2011 and 2014 using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which includes data about health conditions and risk factors. The survey findings showed that almost two-thirds reported at least one ACE and more than 25% experienced three or more ACEs. It is important to note that this study solely focused on abuse and household dysfunctions because items assessing neglect were not included in the BRFSS until 2019. (CDC, 2021). These findings highlight the high prevalence rate of ACEs reported by adults living in the United States.

Several meta-analytic reviews have assessed the relations between ACEs (i.e., assessing abuse, neglect, and house dysfunction) and negative outcomes and family functioning for adults. One specific systematic meta-analysis examined the relations between ACEs and health outcomes and included 96 studies (Petruccelli et al., 2019). Across these studies, regardless of baseline levels of adjustment, there was a significant association between the presence of a single ACE and all psychosocial/behavioral health outcomes (i.e., alcohol problems, illicit drugs, anxiety/panic, and depressed mood) excluding hallucinations (Petruccelli et al., 2019). A more recent meta-analysis included 63 studies and investigated the prevalence of ACEs in studies using the ACE International Questionnaire (Pace et al., 2022). Of the 63 studies, the average sample size across studies was 1,247 participants, and the results showed that, on average, 75% of the participants in the studies experienced at least one ACE (Pace et al., 2022). Given the literature, it is well-researched that adults are reporting ACEs.

Prevalence of ACEs in Adolescence

It is important to know the incidence of ACEs in adolescence and how they are related to socio-emotional and behavioral health outcomes during this developmental timeframe. For example, Broekhof and colleagues (2022) investigated the prevalence of ACEs in a sample of Norwegian adolescents. The sample was split almost evenly between boys (51%) and girls (49%) with a mean age of 15. These authors found that among 8,199 adolescents, nearly two-thirds of participants (66%) had experienced at least one ACE and within that group, 28% experienced more than one ACE. The most prevalent ACE category experienced was household dysfunction (62%) followed by abuse (18%) and neglect (7%). The biggest overlap between categories was neglect and abuse as 19% of youth reported experiencing both categories of ACEs (Broekhof et al., 2022). Overall, this study highlighted high prevalence rates of ACEs among a large adolescent sample.

Studies have also focused on American youth and examined the prevalence of ACEs among patients from a larger parent study, the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development 14 (ABCD) study (Nagata et al., 2022). Participants included 10,317 United States youth (49% female and 46% representing a racial and/or ethnic minority group). Results showed that 81% of youth reported experiencing at least one ACE (Nagata et al., 2022). Another study examined the prevalence of ACEs with a majority minoritized group. Burke et al. (2011) investigated the prevalence and outcomes of ACEs among youth living in low-income urban areas. In a sample of 701 youth (ages 0 – 21; 54% female), the majority identified as African American (58%), and nearly two-thirds of participants (67%) reported experiencing at least one ACE. Furthermore, 12% of the youth reported four or more ACEs. Additionally, in a study of 241 African American high school students living in Houston, Texas, 51% of youth reported 4 or more ACEs. The most frequently endorsed ACEs included a close friend or family member’s death (72%), physical aggression (56%), witnessing community violence (48%), and having parents divorced (47%) (Freeny et al., 2021). Overall, adolescents commonly reported ACEs; however, due to the possibility of youth not understanding their level of experiences with trauma, the actual rates of ACEs might be even higher than the reported prevalence rates (Burke et al., 2011).

Prevalence of ACEs in Emerging Adulthood

Due to adolescents commonly reporting that they experienced at least one ACE, it can be inferred that emerging adults would also have experienced high levels of ACEs. One study focusing on Latino/a emerging adults found that among the 1,065 individuals, 50% reported experiencing at least one ACE, and only 18% reported having no ACEs. Additionally, up to 30% of participants reported experiencing four or more ACEs (Forster et al., 2020). Along similar lines, in another study of 880 emerging adults (46% Latino/a), results found that 25% of the sample reported at least one ACE (Davis et al., 2021). The previous study provides information about the prevalence of ACEs among Latino/a emerging adult populations, however, there has been relatively little specific research on the prevalence of ACEs in emerging adulthood (18 – 25 years of age) in the United States.

Most studies focusing on the prevalence of ACEs in adulthood examined broader age ranges that did not primarily focus on emerging adults. One study examined the prevalence of ACEs among 284 emerging adults (Mage = 20) who attended college and lived in the northeastern United States (Nikulina et al., 2017). A total of 24% of students reported at least one ACE and 11% reported five or more ACEs (Nikulina et al., 2017). When examining a similar sample of 239 college students in the United States, consistent results were found (Karatekin, 2018). A total of 22% of students reported one ACE and 8% reported four or more ACEs (Karatekin, 2018). Although these studies inform us that ACEs are being experienced by emerging adults, the findings from college students cannot necessarily be generalized to the broader population of individuals in this age range. In particular, this sample is limited because it consisted of a Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) sample of college students and a substantial percentage of emerging adults are not in college (Arnett, 2000).

Although few studies in the United States examined the prevalence of ACEs among emerging adults in non-WEIRD populations, researchers from other countries have conducted these types of studies. In an emerging adult sample (n = 483) from Botswana, Amone-P'Olak (2022) found that 21% of participants reported experiencing one ACE and 13% reported experiencing two ACEs. Surprisingly, the rate of experiencing three or more ACEs rose to 40%, and 15% of emerging adults experienced five or more ACEs (Amone-P'Olak, 2022). In addition, Dar et al. (2022), examined the prevalence of ACEs among emerging adults (n = 693) in India. They found that the majority of participants (88%) reported experiencing at least one ACE, 33% experienced 2-3 ACEs, 26% were exposed to 4-6 ACEs, and 15% reported 7-10 ACEs. Along similar lines, Villanueva and Gomis-Pomares (2021) examined the prevalence of ACEs among emerging adults in Spain (n = 490). The results showed that divorce and/or parental separation was the most frequent ACE reported by 26% of participants, followed by household substance abuse (18%) and physical abuse (16%) (Villanueva & Gomis-Pomares, 2021). These few studies showed a high prevalence of ACEs (i.e., in the United States, Africa, Spain, and India) but also highlight the need for additional research in this area.

Relations between ACEs and Health Outcomes

Several studies showed the detrimental effects of ACEs on health outcomes among adults (e.g., Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2017). Felitti and colleagues (1998), found positive relations between the number of ACEs experienced in the three categories and negative health consequences and risk behaviors among 8,056 adults ranging in age from 19 to 92. Additional studies in the literature have also found an association between ACEs and health outcomes including substance use (Dube et al., 2003) a majority of females (i.e., 54%) and white (73% women; 75% male) participants. In addition, in a recent meta-analysis including 37 studies and 253,719 participants, the overall number of ACEs endorsed by participants was associated with an elevated risk for negative mental and physical health outcomes later in life (Hughes et al., 2017). Overall, across multiple studies investigating ACEs and health outcomes, there is a consistent finding that ACEs are associated with detrimental outcomes such as self-reported daily stress (Mosley-Johnson et al., 2021), depressive disorders (Chapman et al., 2004) and health anxiety (Reiser et al., 2014). Many studies examining ACE outcomes focus on adult populations, and more research is needed to better understand ACE outcomes in adolescent and emerging adult populations.

ACEs are not only associated with physical and mental health but also with risk-taking behaviors such as substance use. A scoping review examined the associations between ACEs and diagnosis of substance use in later life (Leza et al., 2021). This review included 12 studies with sample sizes ranging from 30 to 21,554 with primarily adult populations. The findings showed a positive association between reports of ACEs and the development of substance use disorders (Leza et al., 2021). The presence of negative health outcomes among adults who report ACEs highlights the importance of preventing ACEs and identifying risks and promoting protective processes earlier in life that may prevent later health issues.

Substance Use in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Substance use involves a wide range of drugs, including tobacco (e.g., cigarettes and cigarillos), alcohol (e.g., beer, wine, and liquor), inhalants, and drugs. Tobacco is a plant that contains a highly addictive chemical known as nicotine. Tobacco leaves are cured and fermented allowing for the product to be consumed in multiple ways such as smoked (cigarettes), chewed (chewing tobacco), and/or inhaled (snuff). Recently younger generations have been smoking tobacco electronically through e-cigarettes or vapes. Alcohol is categorized as a depressant that is made through the chemical change of fermentation that uses yeast and sugar. Alcohol can be fermented and applied to various beverages such as beer, wine, and liquor which are typically drunk. Inhalants are a substance category in which a solvents-producing vapor is inhaled to feel euphoric-like symptoms. The three major types of inhalants are aerosols, volatile solvents, and gases spray paints, hair sprays, and markers. Lastly, drugs as any chemical substance that may change how your body and mind work, legal or illegal. Substance use can include a variety of drugs that affect the mind and body in different ways potentially resulting in detrimental outcomes such as addiction or health alterations.

Substance Use in Adolescence

It has been consistently shown that adolescents use drugs that would be deemed illegal based on United States drug laws (CDC, 2022). The legal age for alcohol and tobacco use in the United States is 21. Other drugs such as inhalants are not regulated under drug laws in the United States. However, some states have laws to not sell potential inhalant products to people under 21 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2024). The legal status of drugs is complicated because drugs encompass a range of legally prescribed substances that can also be illegal. The way that adolescents engage in substance use is consistently changing, creating a need for continued research.

The most frequently used drug among adolescents is alcohol (CDC, 2023). Findings from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) showed that, among a nationally representative sample of adolescents, 29% reported underage drinking of alcohol in the past 30 days (CDC, 2023). Furthermore, using the same YRBS, 16,513 adolescents reported having their first drink that was more than a few sips before age 13 (CDC, 2023). Using a separate survey in 2002, further studies examining 8th, 10th, and 12th graders nationally for the Monitoring the Future Survey found that youth reported substantial alcohol use in the past 30 days (Windle, 2003). A total of 20% of 8 th graders, 35% of 10th graders, and 39% of 12th graders reported alcohol use in the past 30 days. While this indicates that alcohol is broadly used among adolescents, recently, nicotine vaping has been identified as one of the most used substances by youth using the 2022 Monitoring the Future Survey data (National Institute for Drug Abuse, 2022). For example, the percentage of 8 th graders who vaped nicotine (7.1%) was higher as compared to alcohol (6.0%) and cannabis (5.0%) use (Monitoring the Future, 2022).

Polysubstance use in adolescence most commonly includes tobacco/nicotine and alcohol (Surati et al., 2021), and some research focused on specific patterns of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine use. For example, Coulter et al. (2019) used a latent class analysis (LCA) to identify six classes of polysubstance use among 119,437 youth who completed the 2015 YRBS. The six classes identified were nonusers (62%), medium-frequency three-substance users (4%), high-frequency three-substance users (4%), experimental users (12%), marijuana-alcohol users (15%), and tobacco-alcohol users (4%; Coulter et al., 2019).

Potential Detrimental Consequences

Using substances during adolescence can have potentially detrimental short- and longterm consequences for physical and mental health, with some substances (e.g., illicit drug use) having greater health consequences than others (Larm et al., 2008). Further studies have shown that early substance use is associated with behavioral outcomes and changes in neurodevelopment. Neuro abnormalities have been found in white matter quality and brain structure volume among adolescents who reported 1-2 years of heavy drinking, defined as consuming at least 20 drinks per month (Squeglia et al., 2009). Furthermore, early, and more constant use of alcohol and marijuana has also been associated with risky behaviors. Guo et al. (2002) investigated the developmental association between alcohol and marijuana use in adolescence and risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood. In a longitudinal study following an urban sample of 808 adolescents for ten years beginning at age 10, Guo et al. (2022) found that adolescents’ substance use predicted risky sexual behaviors when controlling for early sexual behaviors. Additionally, marijuana users and binge drinkers were less likely to use protection and had significantly more sexual partners compared to non-marijuana users and nonbinge drinkers (Guo et al., 2002). These studies showed that the consequences of substance use during adolescence have multiple potential detrimental outcomes affecting behavioral, neurodevelopmental, and psychosocial outcomes.

The available evidence seems to suggest adolescents use substances in various capacities. The most used drug reported is alcohol, although it is considered illegal under United States drug laws. However, regardless of the frequency of substance use, it is linked to detrimental outcomes such as health and risky behaviors. Due to the potential consequences of early substance use, it is important to understand circumstances that may trigger it while also understanding the role of potential protective and vulnerability factors.

Substance Use in Emerging Adults

Studying substance use among emerging adults raises challenges because once individuals turn the age of 21, many substances are legal such as alcohol, tobacco, and nicotine. According to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health in 2018, more than one-third of emerging adults (aged 18 to 25) in the United States reported binge drinking in the past month and 1 in 11 emerging adults reported being a heavy drinker (i.e., binge drinking on five or more days in the past month). When looking at individual substances emerging adults report engaging in high rates of alcohol use (60%), illicit drug use (22%), and cannabis use compared to other developmental periods (SAMHSA, 2014). Additionally, about 2 in 5 emerging adults reported using an illicit drug in the past year (SAMHSA, 2018). About one-fourth of all heroin users are emerging adults in the United States (SAMHSA, 2014). In 2018 there were about 34.1 million emerging adults. Alcohol and marijuana are the most commonly reported used drugs among emerging adults (SAMHSA, 2018). Overall, it is known that emerging adults use substances, however, most research on prevalence examines substance use as it relates to substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2018).

There is evidence that emerging adults routinely use substances such as alcohol and illicit drugs (SAMHSA, 2005). In a related line of literature on substance use disorders, researchers showed that many emerging adults struggle with substance use disorders (Volkow et al., 2021). The 2018 National Survey of Drug Use and Health found that, among emerging adults, 1 in 7 have substance use disorders, 1 in 13 have illicit drug use disorders and 1 in 17 have marijuana use disorders (SAMHS, 2018). When investigating more hard-core drugs (i.e., cocaine), emerging adults also reported taking these types of drugs in the past year. In addition, about 1 in every 14 emerging adults have used hallucinogens, 1 in 17 have used cocaine, 1 in 125 have used methamphetamine and 1 in 200 have used heroin in the past year (SAMHS, 2018). Based on the evidence available, it seems fair to suggest that emerging adults are engaging in illicit drugs but not in high quantities.

Potential Detrimental Consequences

Generally, substance use has been correlated with negative outcomes affecting one's physical, mental, and/or emotional health. The literature on substance use consequences in emerging adulthood is limited due to most research focusing on adolescents and how substance use affects them into adulthood. This research focus contrasts with an approach that focuses specifically on emerging adults. Given the literature on emerging adults, it can be assumed that the consequences of substance use would be different due to the difference in life patterns and stressors. One study examined substance use (i.e., use of alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines, opiates, and tranquilizers) among emerging adults who identified as college students to investigate associations between this outcome and personality and gender (Kashdan et al., 2005). The sample included 421 emerging adults (53% women; Mage = 19) who identified as European (88%). For men, participants who smoked and drank alcohol were more likely to engage in marijuana use (Kashdan et al., 2005). The literature on substance use in emerging adulthood is limited for two possible reasons. One is that many drugs becoming legal during this development period and/or the other is the challenge of a representative sample of emerging adulthood. The current study addressed some of these limitations.

The literature surrounding substance use as it pertains to emerging adults is limited in many ways. Most of the literature focuses on adulthood, rather than breaking it into smaller portions such as emerging adulthood. Additionally, when the literature examines emerging adults, it solely focuses on college students which is not representative of everyone in this developmental period. However, the available literature shows substance use among emerging adults, particularly alcohol and marijuana. When examining the literature on the consequences of substance use among emerging adults, it suggests an association with personality outcomes, mental health, and deeper substance issues.

Association between ACEs and Substance Use in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Adolescence

Several studies showed associations between ACEs and substance use in adolescence. Studies addressed alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, illicit and other substances that included: (a) alcohol initiation and use (lifetime, past 30-days, daily, binge drinking, and intoxication) (Afifi et al., 2020; 2021; Broadbent et al., 2022; Dube et al., 2006; Duke, 2008; Meeker et al., 2021; Stritzel, 2022), (b) use of cigarettes and/or electronic vapor products (lifetime, past 30-days, daily) (Afifi et al., 2020; 2021; Broadbent et al., 2022; Duke, 2008; Stritzel, 2022), (c) cannabis use (past 12-months, past 30-days, daily) (Afifi et al., 2020; Duke, 2008), (d) illicit drug use (lifetime, past 30-days) (Dube et al., 2003; Stritzel, 2022), and (e) substance use other than alcohol or cannabis (Meeker et al., 2021). The studies are organized by the type of study framework they used (i.e., retrospective chart review, cross-sectional, and longitudinal).

In a retrospective review of medical charts for adult members of the Kaiser Health Plan in the United States (Mage = 55 for women and 57 for men; 74% white; 54% female), Dube et al. (2006) examined relations between 10 ACEs assessing three categories including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and alcohol initiation. The authors found that the presence of 9 ACEs, apart from physical neglect, was related to increased odds of ever drinking alcohol and that participants with the greatest odds of ever drinking alcohol were those with four or more ACEs. Among participants who reported ever drinking alcohol, all 10 ACEs were associated with a higher likelihood of initiating alcohol use during early adolescence (14 years old or younger), and 9 ACEs, except for physical neglect, were related to a higher likelihood of initiating alcohol in mid-adolescence (15 to 17 years). The strongest association between ACEs and alcohol use was found during early adolescence (Dube et al., 2006). In another study with the same sample, Dube et al. (2003) found that ACEs significantly increased the odds of initiating illicit drug use (i.e., “ever-used street drugs”) during early and mid-adolescence for each category of ACE scores, and more generally increased the odds of having drug problems or being addicted to drugs.

When using a cross-sectional approach to examine ACEs and substances, the findings support the retrospective results that there is an association between the two. Among a primarily white sample, (69.2%) of youth in 8th, 9th, and 11th grades (ages 12-19) who completed the 2016 Minnesota Student Survey (MSS), ACEs assessing abuse (i.e., verbal, physical, and sexual) and household dysfunction were associated with a higher likelihood of initiation of alcohol or cannabis use by age 14, daily alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use, and binge drinking in the past 30-days (Duke, 2008). With the addition of each ACE, the likelihood of early initiation of alcohol or cannabis use, daily alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use, and binge drinking increased from 30% to 48% (Duke, 2018). In a separate study using the 2013 MSS that was completed by 7 th and 9th graders (n = 79,339; 75% white; 26% reporting 1 or more poverty indicators), experiencing either any abuse, any household dysfunction, or a combination of both significantly increased the likelihood of initiating alcohol use by or before age 14 for boys and girls (Chatterjee et al., 2018). Similar findings among a primarily white (61%) group of adolescents of those reporting at least two ACEs had significantly higher odds of using alcohol, cannabis, or other substances, or being intoxicated during school (Meeker et al., 2021). Additionally, when examining this association in a minoritized sample, the total number of ACEs reported by youth significantly increased the likelihood of alcohol, illicit drug, and cigarette use in the past month (Stritzel, 2022).

This relationship of ACEs and substance use is also identified in non-American samples. Among Canadian adolescents ages 14 to 17 (52% female), except for poverty, spanking, and parents’ divorce/separation, all ACEs were significantly associated with past-12-months of alcohol use, binge drinking, and intoxication. Apart from spanking, all ACEs were significantly associated with both lifetime and past-30-day cigarette use. In contrast, electronic vapor products were significantly related to 6 ACEs that focused on household dysfunction, parents’ gambling and trouble with the police, and emotional abuse. Lastly, all ACEs, with the exception of spanking, were associated with past 12 months and past 30-day cannabis use (Afifi et al., 2020).

Several studies reported that ACEs and substance use are significantly associated, however, fewer studies used longitudinal data to inform the field on how this association works overtime. Broadbent et al. (2022) assessed the degree to which ACEs predicted lifetime use of alcohol and tobacco (i.e., cigarettes and chewing tobacco) across five waves of data (n = 482) where adolescents were 10-13 years old at the first and 15-18 years old at the last wave of data collection (70% white; 51% female). The measure of ACEs included eight items based on constructs in the Felitti et al. (1998) measure with some ACEs reported by adolescents (e.g., parental punishment and psychological control) and others reported by parents (e.g., self-report of depression, household financial difficulties, and divorce/instability in the marriage). When examining the relation between ACEs and substance use, there was a significant association between ACEs at Wave 1 and tobacco but not alcohol use at Wave 2 (Broadbent et al., 2022).

The literature on ACEs and adolescent substance use shows an association between the two. Specifically, the number of ACEs an adolescent report, the more likely they are to engage in substances across various timeframes (i.e., past 30 days, lifetime). However, there are a few limitations to the literature. The main limitation is the lack of diversity in the samples. Many of the samples included a majority white sample, leaving minoritized groups out or making up a small percentage of the sample. This creates a significant gap in the literature on the relations between ACEs and substance use. It is important to acknowledge in the literature that some measures used parent reports rather than adolescent reports. This may create a limitation due to not knowing if what the parent is reporting is accurate to what adolescents are engaging in substances.

Emerging Adulthood

Although relatively more studies focus on the adolescent population, some findings show a similar association between ACEs and substance use for emerging adults (Allem et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2018). One limitation of the literature is many studies on emerging adults focus primarily on college samples rather than samples that can be applied more generally to this age group (e.g., Forster et al., 2018). Prior studies have addressed the relations between ACEs and alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, illicit and other substances (e.g., Rogers et al., 2022). In a narrative literature review, Rogers et al. (2022) examined 43 studies, published from 1998 to 2021, that assessed the relations between ACEs and substance use in emerging adults. Most of the studies (29) focused on emerging adults living in the United States. Across the 43 studies examined, Rogers et al. (2022) found that ACEs were significantly associated with higher rates of substance use including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs across different timeframes (i.e., past 30-days to lifetime). The available evidence from this literature review suggests that ACEs, as a composite, are associated with substance use during this developmental period (Rogers et al., 2022). Further, longitudinal studies are needed to examine this association across time.

In one cross-sectional study, Shin et al. (2018) used LCA to examine the association between ACEs (i.e., assessing abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction) and substance use, among a primarily white (59%) sample of emerging adults (ages 18 – 25; Mage = 22; female 52%). Four classes of ACEs were identified including low ACEs (56%), high/multiple ACEs (16%), household dysfunction/ community violence (14%), and emotional ACEs (14%). Participants in the high/multiple ACEs group reported higher frequencies of alcohol-related problems and current tobacco use as compared to emerging adults in the other classes. Furthermore, those in the multiple ACEs class reported higher levels of increased tobacco use in emerging adulthood compared to participants in the low ACEs class (Shin et al., 2018). In addition, Allem et al. (2015) provided further evidence supporting the relation between ACEs and substance use including outcomes of alcohol, marijuana, tobacco/nicotine, and other illicit drugs in a Latino/a sample. ACEs were significantly associated with the substance use categories including past-month marijuana, cigarette, and hard drug use, and binge drinking. The data in cross-sectional studies showed an association between ACEs and substance use for emerging adults (Allem et al., 2015).

Researchers have also demonstrated longitudinal associations between ACEs and substance use in emerging adult populations. For example, Davis et al. (2021) assessed the degree to which ACEs predicted substance use patterns (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use, binge drinking, and opioid and non-opioid prescription drug misuse) across four waves of data (n = 2526) where emerging adults were 18 years old at the first wave and 22 years old at the last wave of data collection (54% female; 46% Latino/a). A quarter (25%) reported experiencing at least one ACE, using an ACE scale that incorporated emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing parental violence. Using latent transitional analysis (LTA), Davis et al. (2021) identified the degree to which emerging adults transitioned between classes over 3 years. Two groups were distinguished, participants who did not report ACEs compared to those who did report experiencing ACEs. Additionally, across time, three substance use classes were identified including the: (a) high all class (i.e., high endorsement of all substances, including prescription and opioid use), (b) binge, tobacco, cannabis class (i.e., high endorsement of tobacco, binge drinking, and cannabis but low opioid and prescription drug use), and (c) steady binge drinking class (moderate endorsement of binge drinking but no other substances). Participants in the ACEs group tended to stay in a riskier drug use class and were less likely to transition out of it, while also having a high proportion of youth identifying in the high all class. Those who reported high levels of ACEs reported greater earlier binge drinking; the same was found for opioid use. This study suggests that ACEs and substance use are associated, and youth tend to not move across classes once substances are used. Based on the evidence available in the literature, it seems to suggest that ACEs are associated with substance use, more specifically having an earlier and stronger onset of substance use.

Several studies examining the literature on ACEs and substance use within emerging adulthood focused on WEIRD, and college student samples (Forster et al., 2018). The literature using college students is informative, however, has its limitation of not being generalizable to the whole emerging adulthood population or developmental timeframe (ages 18 – 25; Arnett, 2000) and does not include emerging adults who are not attending college. For instance, Forster et al. (2018) examined relations between ACEs (physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and household dysfunctions) and substance use behaviors (past 30-day marijuana, alcohol, tobacco, and hard drug use) in college students. Study findings showed that the overall number of ACEs was significantly associated with college student substance and polysubstance use. Specifically, each ACE was associated with all substance use behaviors, except for verbal and physical abuse (Forster et al., 2018). Similar findings have been found in other cross-sectional studies on ACEs and substance use with college samples (Grigs et al., 2020; Kameg et al., 2020).

Current research showed that ACEs are significantly associated with substance use, specifically alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other substances (Rogers et al., 2022). However, there are many limitations to the literature on emerging adults. One of the primary limitations is the lack of generalizability, with most samples focused either on white individuals (Grigs et al., 2020) or college students (Forster et al., 2018). As Arnett (2000) argued not every emerging adult attend college, some go straight into the workforce or take other paths. It is important to acknowledge the number of ACEs reported in emerging adult populations in the literature. While previous literature has shown that ACEs are experienced by a majority of people, that is not reflected in the studies focusing on emerging adults (Dar et al., 2022). There may be several reasons for the relatively low number of ACEs reported in emerging adulthood relative to adolescence and adulthood because of the developmental period becoming relevant over the past couple of decades.

Theoretical Framework

The literature shows that poverty and related community-level structural factors (e.g., geographic isolation, high residential density and mobility, and low accessibility to resources and opportunities) are associated with higher levels of ACEs and exposure to community violence (e.g., Allen et al., 2019; Cronholm et al., 2025; Parker et al., 1988; Walsh et al., 2019). The CDC Social-Ecological Model describes community-level factors that can contribute to ACEs and exposure to violence. It is known that adversity disproportionately affects African Americans because of historical systemic oppression and intergenerational trauma (Hampton-Anderson et al., 2021). Further, there is a disproportionate representation of African American families in economically marginalized communities due to systemic racial inequities (e.g., racist housing policies – redlining, housing covenants, and economic disinvestment in communities) (Belgrave et al., 2022). Exposure to adversity is balanced by strengths and supports as discussed in the Phenomenological Variant of Ecological System Theory (P-VEST; Spencer, 1997). Both theories are an extension of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model which focuses on the complexity of systems at various levels that affect/surround an individual. Lastly, the transactional-ecological model highlights the interactive nature of risk and protective factors across contextual levels (Giovanelli et al., 2020).

PVEST

In the current study, I examined the association between ACES and substance use and the moderating roles of exposure to community violence and community-based developmental assets drawing from the PVEST (Spencer, 1997). Spencer (1997) builds on Bronfenbrenner’s original model by integrating individuals' intersubjective experiences (Phenomenological Variant of Ecological System Theory; PVEST). PVEST deals with the individual's views and how they understand and interpret the world around them. Variants in the model refer to the different ways that people see the world, emphasizing that this is different from person to person. Lastly, the ecological system refers to the sociocultural influences one may encounter that impact their development. The extension of Bronfenbrenner’s original model was used to help understand how individuals make sense of their experiences in support of intervention or needing support. PVEST also explains the resilience and identity of youth, given their understanding of themselves. The PVEST framework, explains that the risk exposure is balanced by opportunities for support. For example, those who develop in high-poverty environments, also have the support to buffer them from the negative influences of stressors. This support can be found in both internal and external developmental assets.

Spencer's (2006) model of PVEST focuses on five main components. For this thesis, I pulled from a portion of Spencer's model that emphasizes how risk and stress engagement can affect the coping response. PVEST uses the following five components: (1) risk contributors, (2) stress engagement, (3) reactive coping methods, (4) stable coping response and emerging identities, and (5) life stage outcomes to understand one's ability to interpret their circumstances. Risk in the model refers to potential threats that affect development. For example, growing up in low-income urban communities has the potential to contribute to higher chances of adverse consequences on physical health. Stress refers to the specific experiences of threat. Growing up in a low-income urban community, stress may result from the inability to have access to healthcare. Reactive coping methods refer to the maladaptive and adaptive strategies to address stress. Examples of maladaptive behavior can be substance use or aggression, while adaptive behaviors are positive coping skills.

The fourth portion of stable coping response refers to a constant response (e.g., one's identity) of the stress that isn’t easily changed. Here, one’s cultural role and identity may lead to awareness of poor health outcomes, mitigating the outcomes in low-income urban communities. Lastly, life outcomes refer to how the individual views, understands and interprets the challenges while being produced from one identity. Using all five components of the theory yields a mediation approach to the coping methods used to affect the relation between stress and response/life outcomes. The three components of the theory this paper pulls from are (1) risk, (2) stress and (5) life outcomes. Although PVEST’s main concept is to refer to the experiences through mediation, this paper draws from the importance that there is a connection between how stress engagement affects life outcomes. Relevant to the current study, I applied this to understanding how ACEs (stress engagement) were related to substance use behaviors (life outcome) in the context of African American youth living in low-income urban communities, with community violence exposure as a vulnerability factor and community recognition and support as a protective factor.

CDC Model

A secondary theoretical framework supporting the intentional focus on risk and protective factors is the Social-Ecological Model (CDC, 2002). The Socio-ecological model uses a nested four-level interpretation to better understand the occurrence of violence exposure and strategies for prevention of violence. From the lowest level to the highest level, there are: the individual level, the relationship level, the community level, and the societal level. The individual-level explains how individual risk factors increase the chances of being victimized or affected by violence or serve as promotive factors. The relationship-level examines how close relationships (i.e., friends or family) can affect the odds of elevated victimization or violent outcomes. The community-level examines the role of settings, and the risk and societal-level examines broad factors that create environments where violence is supported or deterred.

There is a range of factors that protect or put people at risk for violence exposure. In this model, the individual-level is nested within a relationship-level, which is itself is nested within the community and finally, societal levels (CDC, 2002). I applied this model by examining risk factors at the community and relationship levels, respectively, and how these opposing factors can affect the relation of ACEs that individuals experience and substance use behaviors. This model further expands the understanding of protective factors that may buffer the relations between ACEs and substance use. Assessing protective factors (e.g., community support) that moderate the relation between ACEs and substance use can explain which factors may weaken the impact of ACEs on externalizing behaviors. Relevant to the current study, I applied this model to understand how community violence exposure (risk factor) and community support and recognition (protective factors) affect the relations of ACEs and substance use in the context of African American youth living in low-income urban communities.

Transactional-Ecological Model

Another theory argues the importance of understanding transactional perspectives across different contexts. Originally proposed by Cicchetti and Valentino (1993), the TransactionalEcological model was used to explain how community violence exposure and child maltreatment combine to influence one's adaption and development. However, more recent iterations of this theory also consider protective factors and argue that one's development is influenced by the bidirectional effects of protective and risk factors across multiple contextual levels (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006). In the current study, I examined the transaction of two types of risk at two levels: ACEs (an individual-level risk) and community violence (a community-level risk). I will also examine the transaction between risk and protective factors across two levels: ACEs (i.e., individual-level risk) and community support and recognition (community-level protective factors).

Community Protective and Vulnerability Factors

In addition to assessing the direct effect of ACEs on substance use, it is important to simultaneously study how vulnerability and protective factors may moderate this association. Vulnerability factors occur across socio-ecological levels and strengthen the relation between a risk factor and a negative outcome. Protective factors are characteristics at any socio-ecological level that weaken the association between a risk factor and a negative outcome. In the current study, exposure to community violence was investigated as a vulnerability factor that would strengthen relations between the total number of ACEs and substance use in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Community-level factors (i.e., community recognition and community support for adolescents only) have the potential to serve as a protective factor that will weaken relations between the total number of ACEs and substance use in adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Community Vulnerability Factors

The literature shows that ACEs increase the risk of negative health outcomes including substance use in adolescence and emerging adulthood (Afifi et al., 2020; 2021; Broadbent et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2022). Studies have assessed the role of potential protective processes across socioecological levels in mitigating the impact of ACEs on health outcomes (Bergquist et al., 2024). However, there is a need to examine structural community risk factors that may exacerbate the relation between ACEs and health outcomes.

Prevalence Rates of Exposure to Community Violence

Community violence is defined as violence between unrelated individuals, who might or might not know each other, that takes place outside of the home (Dahlberg & Krug, 2006). Exposure to community violence can be indirect (witnessing) or direct (victimization) experiences of public acts of violence. Witnessing violence is the experience of seeing or hearing about incidents of violence that happened in the community whereas violent victimization is the direct experience of threats of harm or actual physical harm in this context (Richters & Saltzman, 1990).

Prevalence. Definitions of community violence vary, with the broader definitions increasing reported rates of exposure to violence (Overstreet, 2000). Broader definitions include knowing the victims and encompass both witnessing violence and violent victimization. Two subtypes of exposure to violence are typically described in the literature and include witnessing violence and violent victimization. Understanding that exposure to violence affects African Americans at an elevated level, it is important to acknowledge the prevalence in this population, specifically that up to 95% of African American youth have witnessed violence ranging from gun violence to physical attacks (Gaylord-Harden et al., 2011). Among 364 youth (Mage = 13) who lived in low-income areas, the most commonly reported incident was interactions with police (77%), and 24% reported being chased by gangs or other people (Taylor et al., 2016). Although few studies have assessed violence exposure among emerging adults, Ross et al. (2022) found that among 141 emerging adults ages 18 to 22 living in a low-income urban community, 92% reported witnessing one or more violent events and 63% reported being a victim. In addition, Zimmerman and Messner (2013) found among 2,344 individuals, within 80 neighborhoods, violence exposure was 74% to 112% higher for African American youth.

When looking at studies among youth living in higher-income areas, the prevalence rate for exposure to community violence was lower (Stein et al., 2003). When examining the difference between Baltimore's youth living in the inner- versus the outer-city (i.e., high socioeconomic-status youth in Ocean City, Maryland), findings showed some similarities and differences. In a sample of 403 inner-city youth and 435 outer-city youth ages 12 to 24, results showed that inner-city youth reported higher levels of victimization (17% of females and 42% of males reported their life had been threatened), knowing victims of community violence (67% knew of someone who had gotten shot), and witnessing community violence (31% witnessed someone being murdered) compared to the outer city group (Gladstein et al., 1992). Additionally, 95% of males and 75% of females in the inner-city group reported being touched by violence with slightly lower levels of 83% and 74% in the outer-city group (Gladstein et al., 1992).

Several studies found that exposure to community violence led to internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Lambert et al., 2021). Similar findings reveal a spillover effect in that exposure to community violence influenced a number of areas of youths’ lives (e.g., emotional health, academic achievement, and family) (Griggs et al., 2019). Exposure to community violence was also positively related to substance use (i.e., alcohol and drug use, and binge drinking) (Lee, 2012). For example, a study of 10,575 adolescents in three different countries (i.e., the US, Russia, and the Czech Republic) found that the frequency of substance use increased with the severity of exposure to violence (Löfving‑Gupta et al., 2017).

Perspectives on the Intersection of ACEs and Exposure to Community Violence

The Role of Exposure to Community Violence and ACEs

The available literature suggests a co-occurrence of exposure to community violence and exposure to ACEs among minoritized youth living in low-income areas, thus it is important to study how current levels of community violence exposure might exacerbate the relation between ACEs and substance use. Both ACEs and exposure to community violence are associated with detrimental consequences (Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998; Lambert et al., 2021). However, within the ACE literature, much of the current debate revolves around exposure to community violence being considered and measured as an ACE rather than as a variable that may influence the relations between ACEs and health outcomes on its own. The multidimensional ACE scales, which include exposure to community violence, have been examined in a few studies as a variable that would account for adversity in diverse settings (Anda et al., 2010). One study used LCA to identify patterns of ACEs that contained community violence exposure (Lee et al. 2020). Among 10,686 adolescents surveyed across five waves (1994 – 2009) into adulthood, four latent classes were identified; child maltreatment (17%), house dysfunction (14%), community violence (5%), and low adversity (63%). The community violence latent class was composed of individuals who had a high prevalence of witnessing or being directly victimized because of community violence before age 18. When comparing the community violence class with the low adversity class, there was no significant difference among members of either class in their odds of reporting anxiety and depression (Lee et al., 2020). These researchers believe that because a community violence latent class was independently identified as an ACE profile, it should be included to understand multifaceted ACEs. Cronholm et al. (2015) also examined how youth responded to ACEs when a more expanded version was used. They measured the “Conventional” ACEs but added expanded adversities. Expanded ACEs included living in an unsafe neighborhood, experiencing racism, history of foster care, and witnessing violence. Among 1,784 urban youth (45% white, 36% Black; 42% male), more than half reported at least one conventional ACE (73%) or expanded ACE (63%) and 50% reported both (Cronholm et al., 2015). However, only 14% reported an expanded ACE that would have been overlooked by the conventional ACEs. Lee et al., (2020) argued that additional constructs at the community-level need to be added to the original ACE scale, and Cronholm et al. (2015) agreed suggesting that it would create a scale that measures adversity sufficiently for all demographics.

Conversely, one could also argue that exposure to community violence should be examined as its own adversity and measured as something that may exacerbate the effect of ACEs on substance use and other detrimental outcomes. The literature clearly states that there are other predictors that are associated with mental and physical health problems (Finkelhor et al., 2015). It is well-researched that ACEs and community violence both are independently associated with detrimental outcomes, but little research assesses how one can exacerbate the other or even the interaction of the two. It is important to acknowledge exposure to community violence as its own entity. Although ACEs are measured in adulthood, the measure only asks for adversity occurring until age 18. When measuring adversity within adulthood, it looks different and there is no one set scale. If community violence was added to the ACE scale, the importance of measuring it could decrease once one turns 18. Exposure to community violence is an adversity that individuals encounter across the multiple stages of life and may affect their development whenever they experience it. It is possible for one not to experience community violence before the age of 18 but to then experience it after entering emerging adulthood (ages 18- 25). Thus, understanding how current levels of community violence exposure can exacerbate an already detrimental association between ACEs and substance use is important to examine rather than tying it to the predictor. Pulling from the CDC’s Social-Ecological Model (CDC, 2023), the model suggests that violence exposure in the community can spill over on the individual due to it being nested within and its influence on individual and relationship factors. Identifying relevant factors at the community level (i.e., community violence) allows for an understanding of the underlying systemic conditions that give rise to violence.

Community Protective Factors

The identification of protective factors that operate at the community level is critical to understand processes that can ameliorate the relations between the experience of ACEs and substance use among adolescents and emerging adults. Consistent with the social-ecological model (CDC, 2023), prior studies have assessed internal or individual factors (e.g., future aspirations) and external factors (e.g., peer, family, school, and community support) as potential moderators of relations between ACEs and health outcomes including internalizing and externalizing behaviors and substance use (Afifi et al., 2021). Longhi et al. (2021) highlighted that more focus is needed on the role of community factors as moderators of relations between ACEs and health outcomes. The identification of community protective factors can assist in creating interventions to reduce the impact of ACEs on substance abuse during the two key developmental periods. This section focuses on the literature examining the moderating role of community protective factors in related literature on relations between ACEs and health outcomes, with a focus on substance use.

Community support, as defined for the current study, refers to support provided by individuals outside one’s family that assist individuals to develop. Community recognition refers to the way neighbors recognize individuals and help develop social connections. To my knowledge there is no research on community support and community recognition as a protective factor; rather, related literature focuses on broader community aspects (i.e., collective efficacy, involvement in the community, and adult relationships). Although the previous literature does not align with community support and community recognition, it helps inform the way community level factors can affect ACEs and substance use.

Adolescent Studies

Adolescent studies have assessed the role of community protective factors in moderating the impact of ACEs on multiple health outcomes including internalizing and externalizing behaviors and substance use and abuse (Afifi et al., 2021; Bergquist et al., 2024; Lensch et al., 2021; Strizer, 2022). Community protective factors included collective efficacy and community involvement, and these constructs have been assessed in community and clinical samples. Several studies have also explored the role of protective adult relationships, including nonparental adult mentors, as moderators of the impact of ACEs on health outcomes among adolescents (Afifi et al., 2021; Brown & Shillington, 2017; Lensch et al., 2021). The role of protective adult relationships was examined in the context of both core mentoring (extended family who might provide emotional support) and capital mentoring (rooted in institutions and providing advice) (Gowdy et al., 2022).

Collective Efficacy. One community protective factor that has been widely examined is collective efficacy. Collective efficacy is defined in two ways: informal social control and social connectedness. The first construct assesses the willingness of community members to oversee youth and one another and assist in the presence of threats (i.e., informal social control), and the other focuses on unity and mutual exchange (i.e., social connectedness). Communities with high levels of collective efficacy have shared values and norms, where community members are willing to step in to address problems. Ohmer (2016) investigated the effectiveness of an intervention to increase collective efficacy with 20 individuals (9 youth and 11 adults; ages 16- 32; 70% African American) who lived in low-income communities with high levels of community violence exposure. Results showed that after the program, relations and trust within neighborhoods and social cohesion increased (Ohmer, 2016). Several researchers proposed that higher levels of social cohesion and/or informal social control may moderate the impact of ACEs on health outcomes (Bergquist et al., 2024; Stritzer, 2022).

Community. Focusing on community samples; in one study including 1,912 youth (ages 12 to 18; 50% male; 47% Latino/a, 34% African American, 15% white), Stritzer (2022) examined three-way interactions between ACEs, peer variables assessing peer substance use and unstructured socializing, and neighborhood collective efficacy (i.e., a composite measure comprised of informal social control and social cohesion), and substance use outcomes. Among youth who reported a high total number of ACEs and had peers who used substances, those living in neighborhoods with lower versus higher levels of collective efficacy endorsed higher frequencies of smoking cigarettes. This finding may reflect high levels of parental monitoring and active intervention to address peer and individual adolescent behavior. In contrast, for youth with a high total number of ACEs and higher levels of unstructured socializing, those who lived in neighborhoods with higher versus lower levels of collective efficacy reported higher frequencies of drinking. The author noted that higher levels of collective efficacy may also lead to more trust by adults and less monitoring which could increase rates of drinking (Stritzer, 2022). The way that collective efficacy exerts a protective effect may also differ based on the substance (i.e., smoking cigarettes versus alcohol).

Clinical. For clinical samples, in a study of youth involved with the justice system in Southeast Texas (n = 519; ages 14 to 16; 54% white), Bergquist et al. (2024) assessed whether higher levels of moderated relations between ACEs and a composite measure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (i.e., substance use, anger and irritability, depression and anxiety, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideation). Bergquist et al. (2024) only addressed one aspect related to collective efficacy in their assessment of prosocial community connections that focused on the prevalence of community ties. Significant negative associations were found between prosocial community connections and both ACEs and the composite measure, which showed the promotive role of this community factor. However, prosocial community connections did not moderate the relationship between ACEs and internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Bergquist et al., 2024).

Involvement in the Community and Positive Youth Development Opportunities

Community involvement for adolescents plays a protective role in health outcomes. Community involvement can range from volunteering to positive activities such as sports or clubs (Afifi et al., 2021; Rosenberg et al., 2014). Community involvement can improve health outcomes and strengthen positive youth development. The positive youth development framework emphasizes the importance for youth to engage in their environment in ways that allow for productivity and constructive outlets while also building upon youths' strengths and positive outcomes (Shek et al., 2019). Using a positive youth development framework, involvement in the community may act as a moderator to buffer the relation between ACEs and substance use for adolescents.

Community. Considering community samples, Afifi et al. (2021) examined promotive factors associated with decreased alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis use among adolescents who had experienced ACEs. The sample contained 1002 adolescents (14 – 17 years of age) from Canada who were split almost evenly (52% females). Youth who volunteered once a week or more were more likely to report not using substances (i.e., a composite measure of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use) in the past 30 days as compared to youth who volunteered on a less frequent basis. Youth who agreed or strongly agreed that they felt motivated to help their community were less likely to report substance use in the prior 30 days as compared to youth who were neutral or disagreed with this statement. In addition, youth who participated in school-based extracurricular activities other than sports or physical activities 1 to 3 times a week were more likely to report no substance use in the past 30 days as compared to youth who participated less or more frequently in these activities (Afifi et al., 2021). This suggests that when youth are engaged in activities in/or around the community, it can buffer the association between ACEs and substance use.

Clinical. When examining the association of protective factors on ACEs and substance use among a clinical sample, the findings appear to be similar. Among 350 youth (85% white, 70% male; ages 14 to 17) involved in the juvenile justice system, youths’ involvement in positive activities (e.g., working out, playing sports, being a part of an organized activity like a team or club, having a current or past job, and having done volunteer work) moderated the relation between ACEs (e.g., physical and sexual abuse) and depressive symptoms (Rosenberg et al., 2014). Thus, the effect of ACEs on depressive symptoms was mitigated for youth who reported higher versus lower involvement in prosocial activities (Rosenberg et al., 2014).

Protective Adult Relationships

One aspect that benefits positive development and has been studied deeply is the external support of mentoring. Mentors are people not within your immediate family who can help youth achieve a multitude of things. For example, people who provide mentorship could come from the school setting and the community. Mentorship for adolescents has positive outcomes. Miranda-Chan et al. (2016) followed 2,495 youth in grades 7 to 12 across 15 years to examine healthrelated behaviors of adolescents into adulthood. Results showed that having a naturally occurring mentor during adolescence was associated with positive health outcomes in young adulthood, including psychological well-being, less criminal activity, and greater education attainment (Miranda-Chan et al., 2016). This study informs the literature, showing that when adolescents connect with mentors naturally during the grades of 7 to 12, they have a better chance of positive outcomes later in young adulthood.

When examining mentorship, some researchers divided it into two categories: core and capital mentoring (Gowdy et al., 2022). Core mentors are typically extended family who might provide emotional support, and capital mentors are rooted in institutions and provide social capital and advice but are not connected to the family. When studying core and capital mentors, one study of 4,226 adolescents found that Black youth reported receiving more core mentoring as compared to capital mentoring. Furthermore, the level of parental resources and resourced neighborhoods predicted the frequency of capital mentoring (Gowdy et al., 2022). This study shows the importance of better understanding the presence of access to and the protective function of core mentoring for Black youth living in economically marginalized urban communities, and if the lack of capital mentoring is rooted in systemic issues. Most important is understanding how this category of mentoring may buffer the impact of ACEs on health outcomes.

Relatively few studies have examined the role of community protective factors in moderating relations between ACEs and substance use (Afifi et al., 2021; Brown & Shillington, 2017; Forester et al., 2017; Lensch et al., 2021). These studies are reviewed below and divided into studies focused on community and clinical samples.

Community. For studies focusing on community samples, Forester et al. (2017) found that among almost 80,000 ninth and eleventh graders (75% white), positive student-teacher relationships moderated the relation between ACEs and the non-medical use of prescription medications. Students experiencing higher numbers of ACEs who reported higher versus lower levels of positive student-teacher relationships were less likely to engage in the non-medical use of prescription medications. Along similar lines, Afifi et al. (2021) investigated the role of trust in adults in school and also within the community. Among Canadian adolescents who had a history of ACEs, those who reported having versus not having a trusted adult in the community and at school were more likely to endorse not using substances in the past 30 days.

Clinical. For studies focusing on clinical samples, among 1054 youth (55% female; ages 11-17; 38% white; 27% African American; 24% Latino/a) who were assessed for child maltreatment, Brown and Shillington (2017) assessed direct and moderating effects of protective adult relationships on associations between ACEs and substance use and delinquency. For substance use, no main effects were found for protective adult relationships, however, a significant ACEs x Adult Protective Relationships interaction was found. The relation between ACEs and substance use was stronger for youth with lower versus higher rates of protective adult relationships (Brown & Shillington, 2017). For delinquency, a main effect was found in that protective adult relationships were negatively associated with delinquent behaviors, but protective adult relationships did not moderate relations between ACEs and delinquent behaviors. Along similar lines, Lensch et al. (2021) examined the protective effect of role models. Among 429 youth (73% male; ages 13-17; 42% Latino/a, 34% white; 17% African American) involved in the juvenile system, Lensch et al. (2021) examined the direct and moderating effects of non-parental adult role models on the odds of the occurrence of one health outcome (i.e., either substance abuse or psychological distress) or the co-occurrence of both outcomes. With ACEs included as a covariate, the presence of non-parental role models was related to lower odds of having one outcome as compared to neither outcome. The presence of non-parental role models did not moderate the relation between a high ACE score and the odds of either having one outcome or co-occurring outcomes (Lensch et al., 2021).

Limitations

Some studies that examined the protective role of community-level factors in moderating relations between ACEs and substance use for adolescents appear to contradict each other. For example, when investigating the role of collective efficacy, some studies appear to present it as a strength (Ohmer, 2016), but other literature suggests it does not have a protective effect (Bergquist et al., 2024). However, the literature suggests that being involved in additional activities (i.e., after-school activities and/or positive mentoring) would buffer the association between ACEs and substance use in both clinical and community samples (Afifi et al., 2021; Miranda-Chan et al., 2016; Rosenberg et al., 2014). Although the data suggests a protective effect across several studies (Afifi et al., 2021; Miranda-Chan et al., 2016; Rosenberg et al., 2014), more research is needed that focuses on African-American youth. Lastly, the literature on protective adult relationships adds insights into the importance of adolescents having community-level role models. When examining the constructs individually, there is some evidence that there are community-level factors that can serve as a protective factor in mitigating the association between ACEs and substance use (Ohmer, 2016). However, there are two main limitations in the current literature. The main limitation of the existing literature is the lack of generalizability to minority adolescents. Many of the samples were primarily white samples. Another limitation of the literature to date is the lack of available studies that focus primarily on community-level vulnerability and protective factors and do not examine various substances (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use) but instead focus only on one specific substance (Forester et al., 2017). In addition, several studies incorporate the school context, which can be argued to be its own category. The current study addresses these limitations by focusing on a sample of primarily African American adolescents living in urban, low-income areas. An additional strength of the current study is focusing on community support and community recognition independently rather than combining the two constructs.

Emerging Adult Studies

The literature on the role of community protective factors that may moderate the impact of ACEs and health outcomes is limited. To my knowledge, no literature focuses on the role of community-level protective factors. This is a significant limitation. The current study addresses the gap by investigating the role of potential protective factors at the community-level in moderating the relation between ACEs and health outcomes.

The Current Study

ACEs are associated with negative outcomes such as substance use in adulthood. These outcomes range from mental health to physical health to risk behaviors. More specifically, ACEs have been associated with substance use in both adolescence and emerging adulthood. It has been well-researched that ACEs disproportionately affect African Americans; specifically, people residing in low-income communities. To buffer this association, it is important to understand how protective factors at the community level function. However, the literature is limited due to only focusing on additive factors such as programs. This creates a problem of understanding protective factors that may buffer the association of ACEs and health outcomes in studying minoritized youth living in low-income areas. There is also a need to examine the role of community-level risk factors in exacerbating the relation between the experience of ACEs and substance use outcomes. In particular, the literature shows that African American youth and young adults living in low-income urban communities disproportionately shoulder the burden of community violence exposure in the United States (Belgrave et al., 2022). African American adolescents and emerging adults who live in low-income urban neighborhoods are more likely to bear the burden of high rates of community violence due to systemic racial inequalities that create community-level structural risk factors (e.g., geographic isolation, economic disinvestments, high resident mobility, and low access to resources) which are at the root causes of community violence exposure (Belgrave et al., 2022). This informs the current study due to the samples including a majority of African American adolescents and emerging adults who live in low-income urban areas. These individuals are not a risk factor due to their race/ethnicity, however, due to the circumstances surrounding them. This study advanced the understanding of the interaction of ACEs and community violence and its association with substance use. Additionally, the current study investigated the role of protective factors at the community-level and how they can buffer this association.

Aims and Hypotheses

Based on empirical theories and literature linking stress engagement of ACEs to externalizing behaviors such as substance use and the need to identify vulnerability and protective processes associated with this relation, the present study proposed the following models, and associated aims and hypotheses.

Aim for Model A: This model examined the association between ACEs and substance use, and the degree to which exposure to community violence moderated this association.

Hypotheses for Model A: Model A tested the moderating effects of the vulnerability factor (exposure to community violence) on the relation between ACEs and substance use for adolescents and emerging adults.

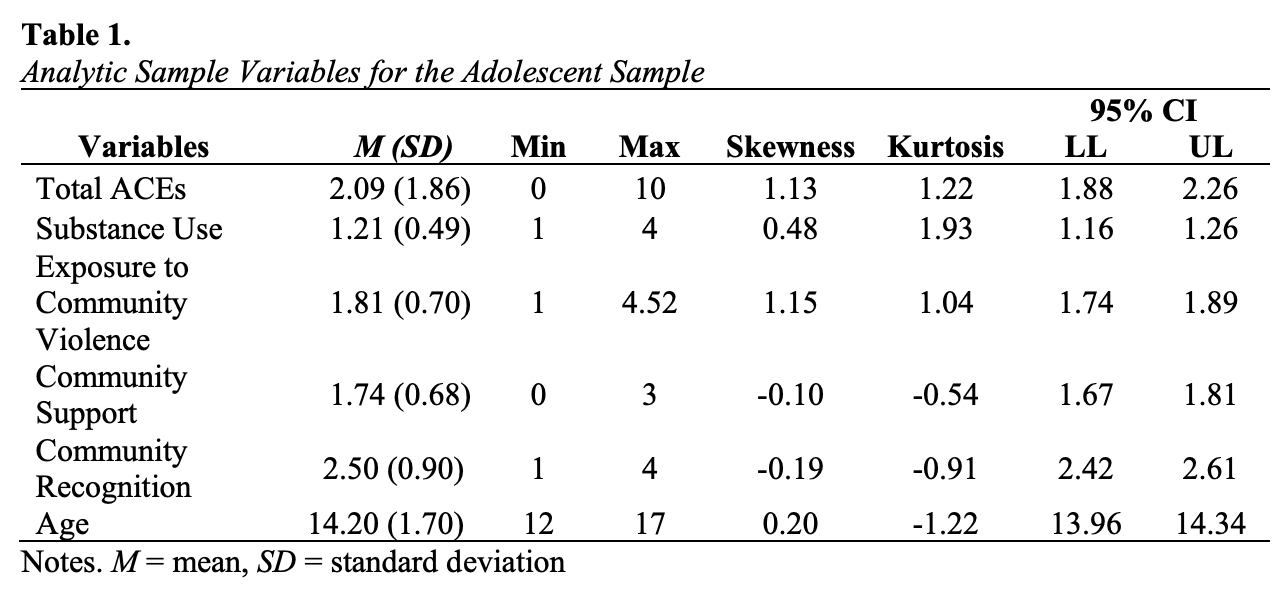

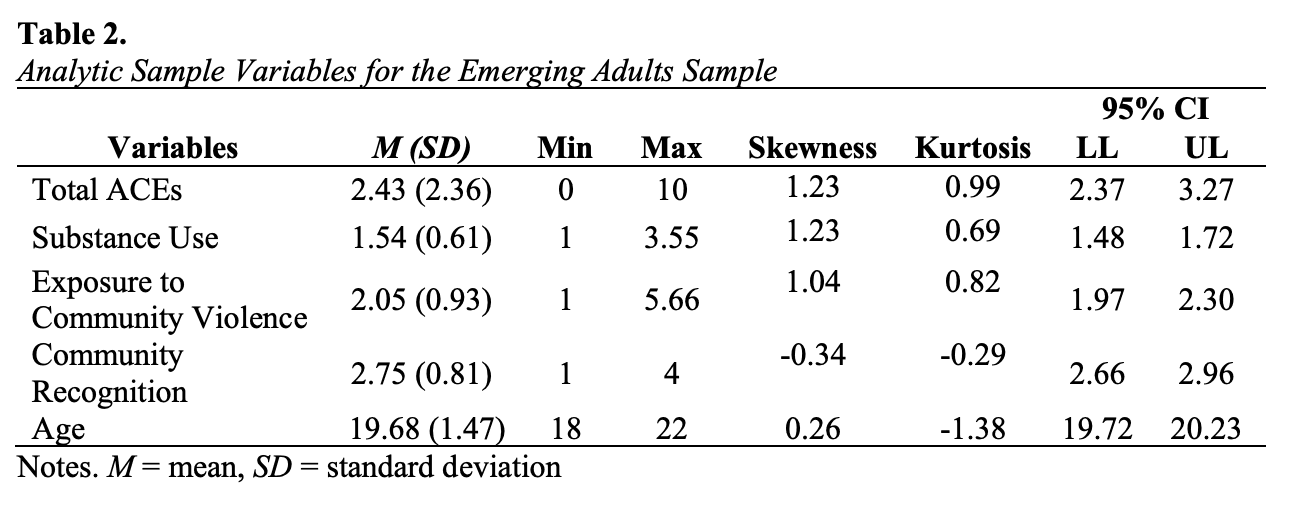

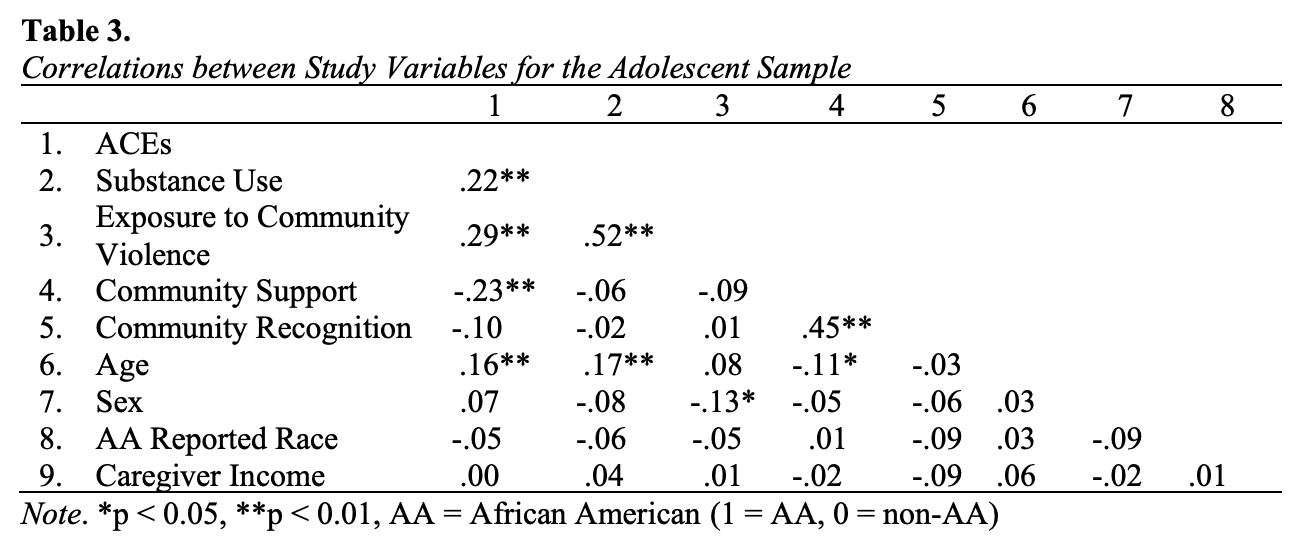

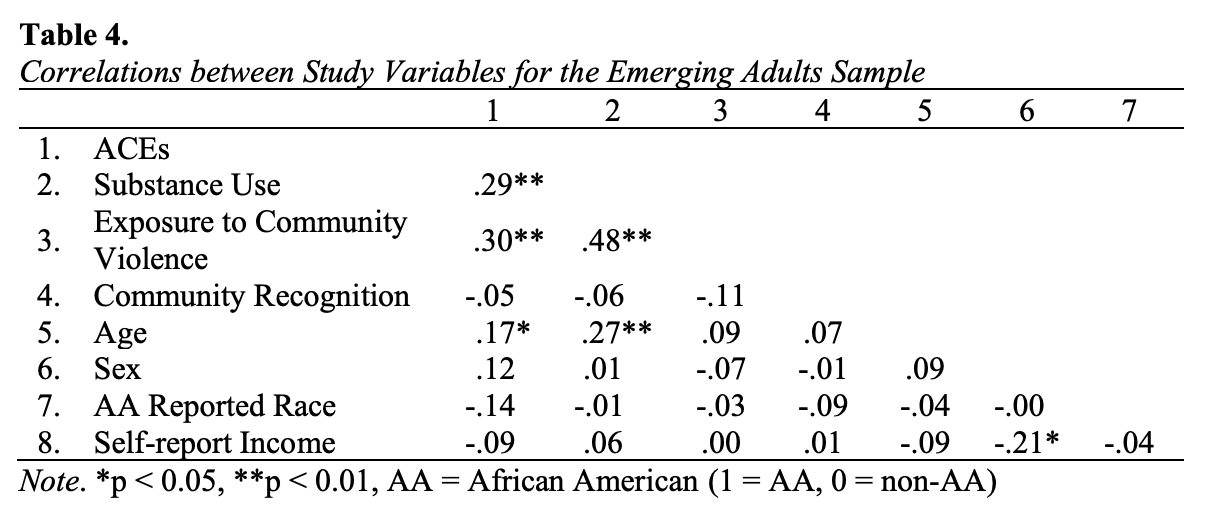

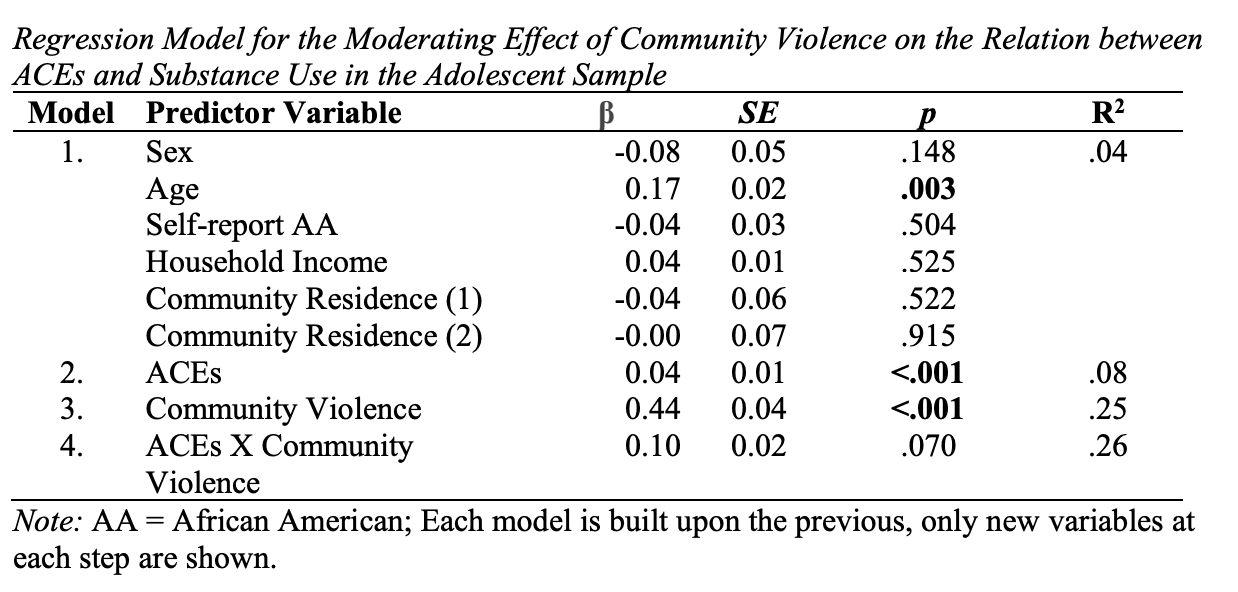

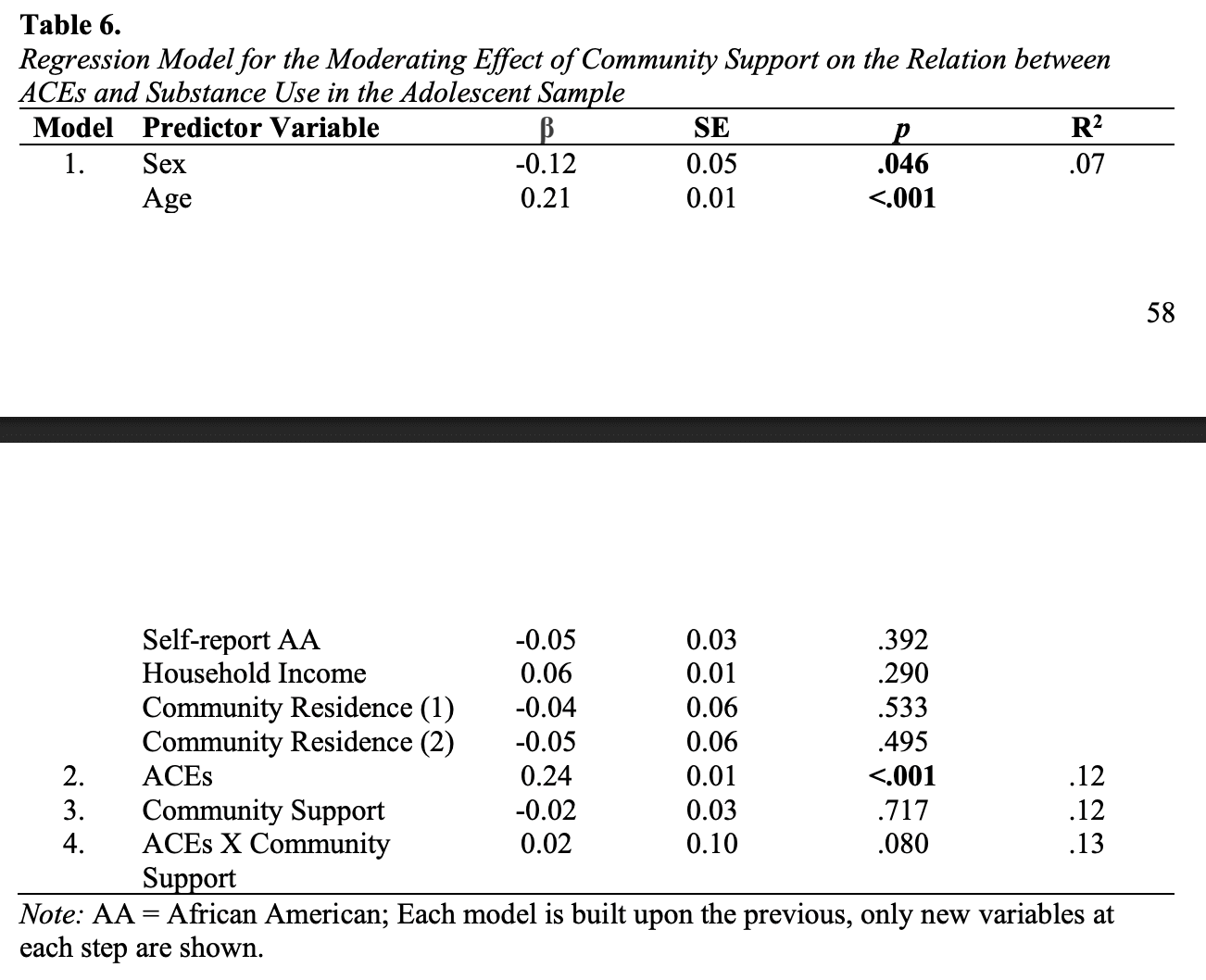

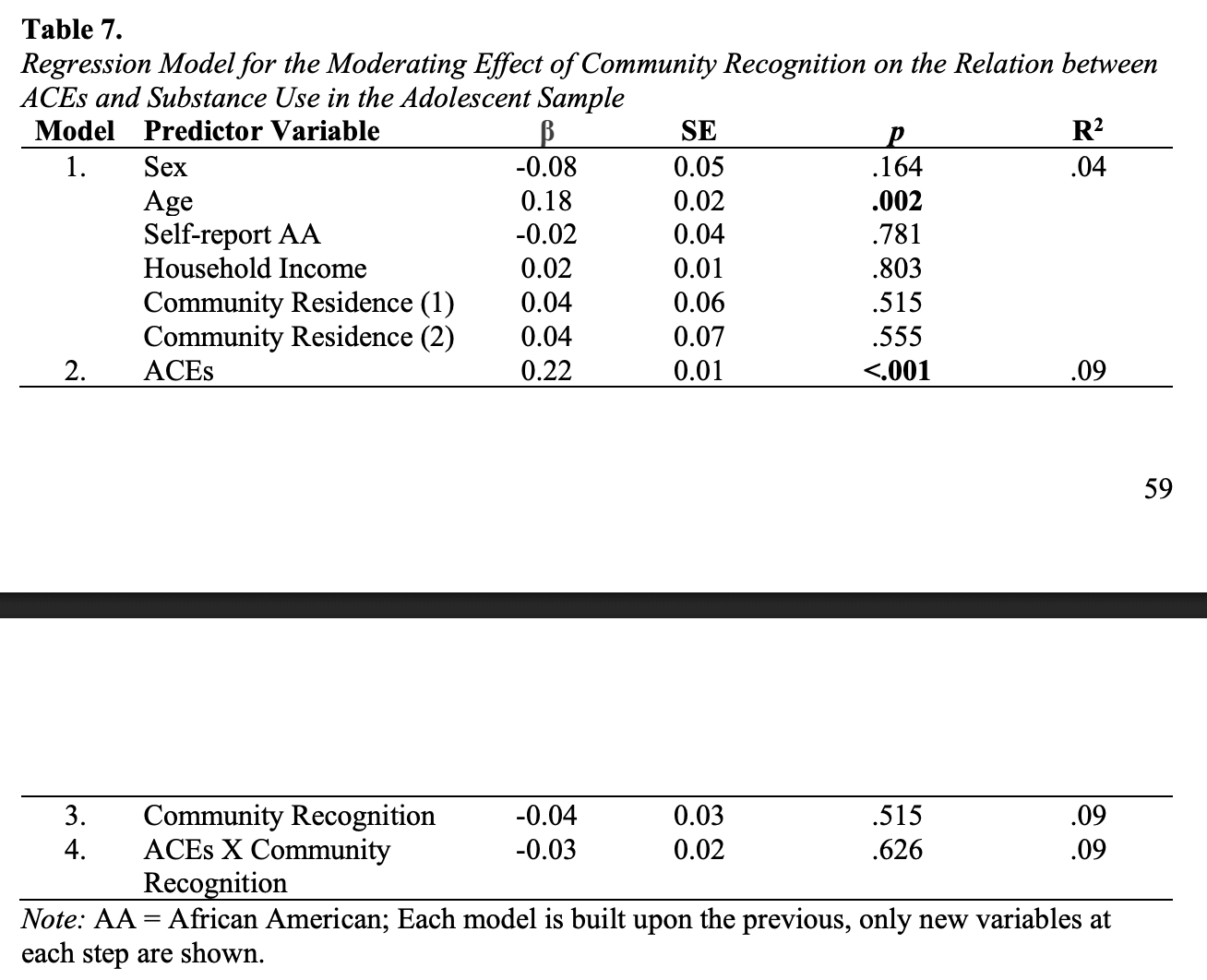

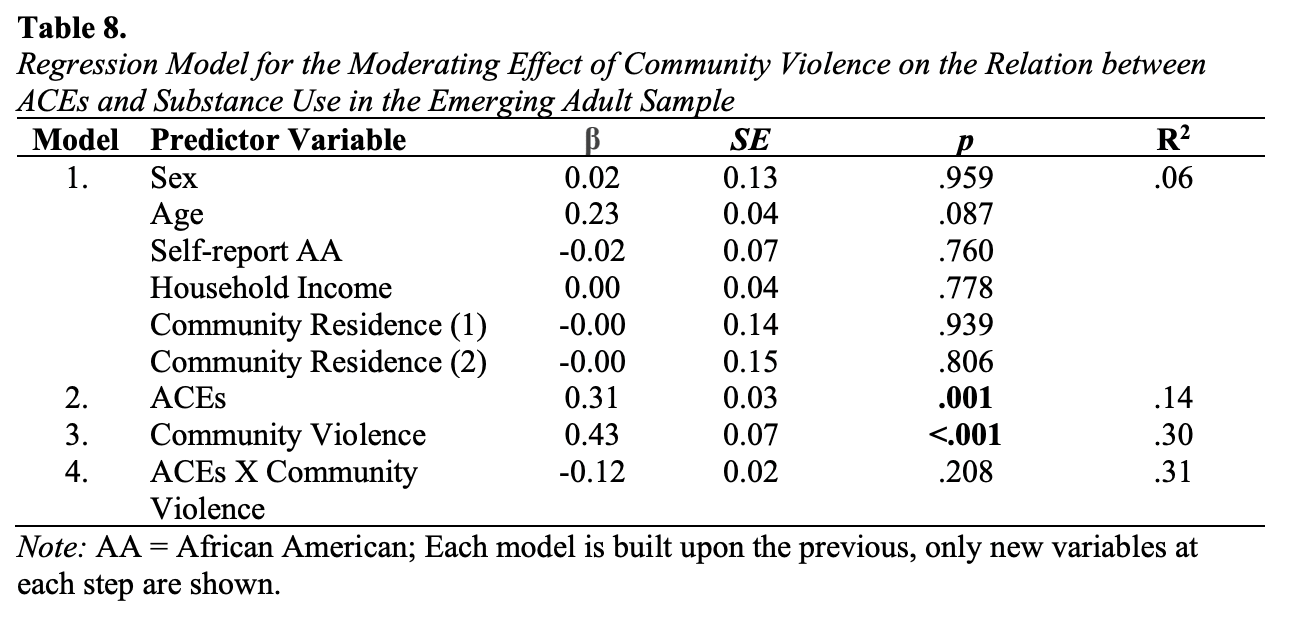

Hypothesis A1: Higher levels of ACEs will be positively associated with substance use in both adolescents and emerging adults.