Abstract

The prevention of fraud against older adults and other age groups, has been the subject of limited research with very few systematic attempts to map different tools and strategies that are used. This paper using the UK and South Korea as a starting point, but other countries too, maps some of the most common tools and strategies used to prevent frauds that target older adults. It develops the first comprehensive typology of strategies built upon the degree to which they embrace modern technology. It shows much of the prevention used is low tech, but high-tech solutions rooted in the fourth industrial revolution technologies are emerging and growing. The paper draws these different strategies and tools together to offer a holistic model for the prevention of fraud against older adults for further debate and utilisation by professionals.

1. Introduction

Individual fraud victimisation in many industrialised countries has become one of the biggest crime risks individuals face. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) in the year ending September 2022, showed fraud accounted for 41% of all crime (ONS, 2023a). Older adults are often viewed as being particularly vulnerable to fraud – although evidence from the CSEW shows they are at least in terms of victimisation, not the highest risk group (see later section). There is nevertheless plenty of anecdotal evidence and research illustrating the devastating impacts of fraud on some older adults (Alves and Wilson, 2008; Button et al., 2014, 2021; Cross, 2016a). Consequently there have been plenty of initiatives to prevent fraud in general and particularly against older adults. There has, however, been no attempt at mapping the diverse preventative measures aimed at protecting individual older adults from fraud, other than one broader attempt at applying the 25 techniques of preventions at fraud in general (Button and Cross, 2017). This paper seeks to provide the first typology of the different tools and strategies which are used to prevent fraud against older adults with particular reference to the level of sophistication of technology used in them. The research is built upon the two countries the UK and South Korea, which are both countries with ageing populations and a significant fraud problem. The typology also illustrates any evidence which exists supporting whether they actually work. The paper ends by drawing together all these strategies to illustrate a model of how these could all be applied together to prevent fraud against older adults (see Fig. 7).

The paper begins by exploring the problem of fraud against older adults, before examining the limited literature evaluating fraud prevention measures either specifically directed at older adults or frauds they are frequently victims of. After setting out the methodology the paper then identifies a wide range of schemes and products directed at fraud prevention. It then groups them according to the level of technology involved, with particular reference to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the level of technology involved. Finally, the paper sets a holistic model for the prevention of fraud against older adults.

2. Older adults, fraud and prevention

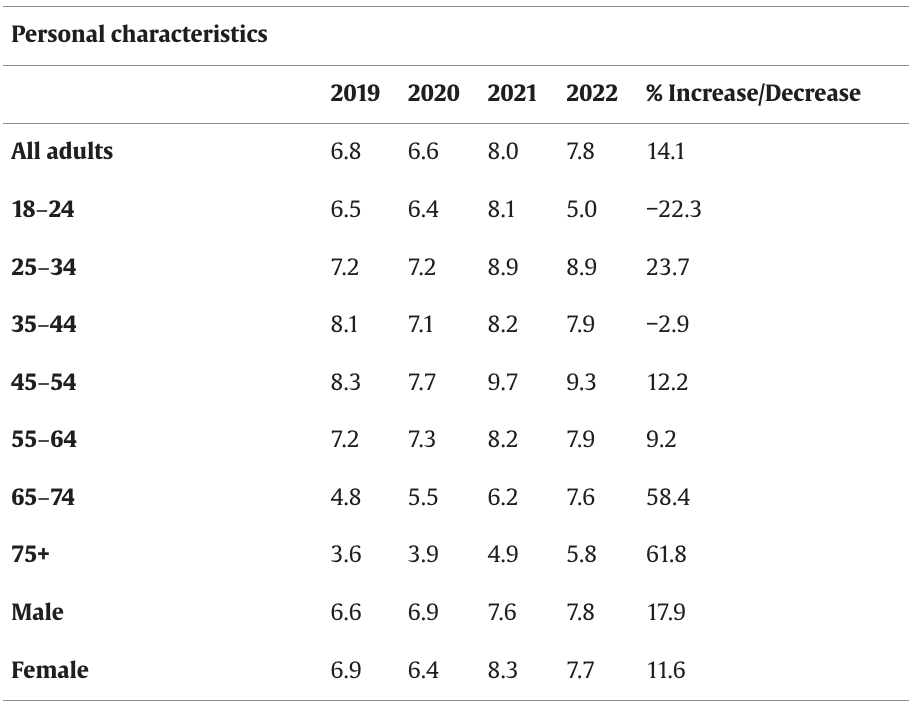

Table 1 illustrates rates of fraud victimisation among older adults in England and Wales between 2019 and 2022. The overall victimisation rate was 7.8% in 2022, which compared to 7.6% for 65–74 year olds and 5.8% for over 75s. The most at risk group was actually 45–54s, at 9.3%, but what is interesting is over this period the two groups with the biggest increase in victimisation are the 65–74 age group (58.4% increase) and over 75s (61.8%). The impact of the pandemic, likely contributing to this increase among older age groups (Kemp et al., 2021).

Table 1. CSEW fraud victims by age group 2019-22 Year ending March (ONS, 2023b).

2.1. Losses to fraud

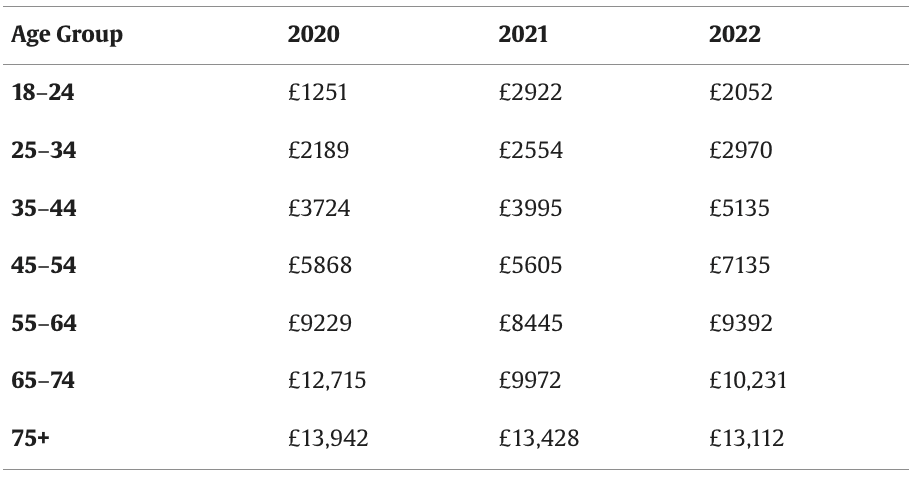

Older adults may not be the most at risk group, but they tend to lose more. Table 2 shows as the age rises so does the average losses, with the 65–74 and 75+ losing the most. Many of these are in positions in life where its harder to recover from losses, dues to fixed pensions.

Table 2. Average losses by age group reported to Action Fraud 2020–2022 Group 2020 2021 2022 (FOI Request).

2.2. Frauds and scams

Fraud and scam are often used interchangeably to describe deceptive behaviours that cause a person some form of financial loss. They are often used as synonyms, although some have noted differences between the two. For instance, Button and Cross (2017) note scams can be deceptive behaviours which cause a loss, which are clearly unethical, but lawful; whereas frauds are always unlawful. Another term important to grasp in this context is financial abuse, which is also a term with much debate on the scope, but generally considered to cover the improper or illegal exploitation or use of funds/resources of an older person (Fealy et al., 2012). It is also usually more associated with those close to the older adult such as family, carers or professionals working with them. Cybercrime is a much broader concept that covers both economic, psycho-social and state cybercrimes (Ibrahim, 2016). This article is only interested in the former along with frauds, scams and financial abuse.

There are a number of methods of fraud and cybercrime which are common vectors for defrauding them. Doorstep frauds/scams: rogue tradesmen who massively overcharge for their services and/or conduct works not required or to a poor standard (Phillips, 2016). Financial abuse of older adults by carers, relatives or friends (Dalley et al., 2017). Telephone scams, where there is high pressure sales of worthless goods or service, particularly investments; impersonation scams that trick victims into transferring money and vishing, where sensitive personal information is sought (Benbow et al., 2022; Carter, 2021; Choi et al., 2017; DeLiema et al., 2020a; 2020b; Lee, 2020; Payne, 2020). Postal scams which utilise fake lotteries, bogus charities and investment schemes to name some touted through traditional mail (Rebovich and Corbo, 2021). The Authorised Push Payment Fraud (APP) where the victim is deceived into authorising a payment to a criminal via impersonation is another common fraud (National Fraud Authority, 2011; Age UK, 2023). Identity frauds: where victims are impersonated to use their financial credentials or identity fraudulently frequently occur (Cifas, 2022; DeLiema et al., 2021). Finally, there are also cyber-frauds covering a wide range of scams using email, the internet and social media (Button and Cross, 2017; Age UK, 2015). Covid-19 has also pushed many older adults towards technological services they didn't previously use which has opened up many more fraud and cybercrimes against them (Benbow et al., 202; Hakak et al., 2020).

Many older adults are lucrative potential targets, as large numbers have lifesavings, retirement pots and investments. Some are also more at risk to fraud victimisation as they fit a trait where there is evidence that makes them more likely to be fraud victims such as suffering cognitive impairment, experiencing health problems, living alone, lonely and a lack of social networks (Alves and Wilson 2008; Cross, 2016b; DeLiema 2018; DeLiema et al., 2018; Duke Hana et al., 2015; James et al., 2014; Judges et al., 2017; Lee and Soberon-Ferrer, 1997; Peterson et al., 2014; Ueno et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2022; Xiang et al., 2020).

3. Fraud prevention literature

This paper will reveal a large number of different initiatives that are and have been used to prevent frauds and scams against older adults. There is, however, very little high-quality evaluation of many of these schemes, as Prenzler (2020, p83-84) notes, regarding the 19 fraud prevention projects found, documented in 24 studies in a systematic review:

Given the size and growth of the fraud problem, it would be reasonable to expect a large number of well-documented intervention studies aimed at demonstrating successful antifraud strategies. However, this does not appear to be the case. The fraud literature has been characterised by descriptive statistics of the dimensions of the problem, and analyses of victim and offender characteristics and opportunity factors, with very little on prevention, especially in terms of applied projects.

Many of the studies on fraud prevention are also directed at organisational and financial statement related fraud (Button et al., 2023a, Button et al., 2023b). The strategies and tools to prevent fraud against older adults that will be explored, many lack evidence of their effectiveness in preventing fraud. This doesn't mean they don't work, rather there is no evidence that proves they do, which raises an important question the authors will return to later in the discussion, over whether it is even necessary to be sure such schemes work using the highest quality evaluations available. This section will briefly explore the smaller body of knowledge that has offered some evidence of effective fraud prevention schemes, however weak. Before this is done it is important to note what is meant by high quality evidence a scheme works.

Sherman et al. (1997, 1998) were able to provide a comprehensive analysis of hundreds of crime prevention projects using the Maryland framework to determine what works in preventing crime and what does not. The Maryland framework has roots in medicine and the use of very high quality evaluations ranging from assessments before and after an intervention has been introduced, through to randomized control trials. This scientific analysis has fundamentally influenced the approach many governments and law enforcement agencies take in their effort to develop effective crime reduction strategies (Sherman et al., 2002; College of Policing, 2022). However, as this section will show the limited literature on fraud prevention generally does not use a methodology that fits this scale. Instead for many there is no evidence or other forms of evaluation are used, some of which evaluate a different issue related to the impact on fraud, such as confidence in spotting frauds or stopping scam call and utilise different methodologies rooted in: literature based studies; views of practitioners or offenders, based upon their past experience through interviews or surveys; experiments with students, members of the public or victims to test whether certain schemes work or not; the use of an existing dataset (such as credit card transactions, with known fraud and correct) which is then tested to produce tools/algorithms to detect/prevent fraud; and surveys of victims and non-victims along with prevention methods and security behaviours they use, to test statistically between the two groups which of these measures may have an impact on victimisation.

The focus of this section will be specific fraud prevention studies relevant to older adults, but it's important to note there are other relevant studies targeted more generally, beyond the scope of this review (see for example Edwards et al., 2017; Leukfeldt and Yar, 2016). One of the most common fraud prevention initiatives relates to fraud awareness training. These measures essentially seek to raise awareness of scams in an individual so they can spot them and avoid falling victim. In one scheme developed and evaluated by Age UK (A UK NGO providing support to older adults) they implemented an awareness raising strategy. The scheme was evaluated using surveys of older adults, telephone interviews with partners and interviews with key stakeholders. The evaluation showed some positive results in terms of increasing the awareness of scams among older adults, improving the feelings of safety and that they were more likely to report scams, among others. However, the evaluation did not explore if it had any impact on victimisation and did not conduct a Maryland level evaluation exploring before and after.

Other research by Mears et al. (2016) suggested that the better educated and more financially secure gain more from awareness raising measures. There is also research which has looked at how older adults are victimised and noted the need for tailored messaging to meet the needs of specific segments of older adults, the types of fraud they are at risk of and the importance of using established forums and networks to disseminate these messages (Oliveria et al., 2016; Xiang et al., 2020). A review of fraud awareness messaging in multiple jurisdictions based upon the views of experts also noted how the use of real case studies of victims was seen as more effective in preventing investment fraud. Studies using experimental research found an important message for potential victims is to not rush financial decisions and postpone them; they found being in a high state of arousal when making such decisions increases the likelihood of being victimised (The Board of The International Organization of Securities Commissions, 2015; Kircanski et al., 2018.

In some initiatives the awareness raising measures amount to much more deeper training. In one scheme in which potential victims received Outsmarting Investment Fraud (OIF) training they were contacted three days later by a skilled telemarketer to ask if he could send information about a proposed investment, of which 18% who had received the training did, compared to 36% in the control group who hadn't received the training (Shadel et al., 2010). Although clearly a positive the experiment didn't involve a test of victimisation and was only three days after the training.

Reverse boiler rooms have also been used in some schemes where the authorities conduct fake scams calls to potential victims to see if they are susceptible. This has also been used for websites, fake phishing emails, leaflets etc. In one study several experiments were undertaken where potential victims were given fraud awareness training and then several days later telemarketers pretended to be scammers and contacted them with a fake scam to determine if the now trained potential victims would still be susceptible, alongside a control group with no training. Those who were victims of the scam were then offered further help to try and prevent them doing so again (AARP, 2003). The various experiments showed response rates to the scams could fall by half in some cases.

In another scheme (Project Sunbird) in Australia through the use of financial intelligence to determine payments being made to West Africa, the police wrote to these potential victims warning them to stop paying fraudsters. As a result of this intervention, 73% stopped sending money after the first letter, and 87% after the second letter (Cross, 2016b).

Call blockers have also become a tool to prevent telemarketing fraud. There are a variety of products and apps available and they do vary in how and the amount of scam/nuisance calls they block. In one scheme, however, the use of Truecall's technology (which essentially blocks all but approved numbers - and there are variations on the system), in an experiment with 1084 devices fitted found 99% of scam and nuisance calls were blocked, 99% of those in the scheme also felt happier as a result of the calls being blocked and the scheme claimed a 32–1 return on investment (National Trading Scams Team, 2020). Another evaluation of the same product found positive results too (Rosenorn-Lanng and Corbin-Clarke, 2020, p 91). Both these evaluations provide clear positive evidence of the benefits of call blockers, but again there is no evidence they actually reduce victimisation – although one could theorise the reduced opportunities would have an impact.

Another important type of intervention which has been advocated and evaluated is the specialist training of those professionals who work with older adults to spot potential fraud victimisation or financial abuse to report such behaviours or if feasible to intervene to stop victimisation. There have been a variety of schemes targeted at roles such as social workers, healthcare workers and bankers to name some. In a large experimental study AARP Public Policy Institute (2019) developed a programme of training for bank staff to recognise financial exploitation in older adults and to intervene by reporting it, with 82 participating branches and ultimately 1816 participants (bank staff) allocated to control and experimental groups. The experimental group were much more likely to report abuse and saved $900,915 compared to only $54,384 in the control group. In a study of medical professionals who were trained to recognise financial exploitation a study illustrated a positive view of the programme and 6 months after the programme with 24 of those completing questionnaires (from 67 who agreed to take part in the evaluation) had identified 25 patients vulnerable to financial exploitation (Mills et al., 2012, p 358).

It was noted earlier isolation and mental health issues were associated with increased risk of fraud victimisation. Social prescribing, where individuals are referred to non-clinical services to enhance their well being, such as fitness clubs, arts groups, social groups to name some, have been identified as a potential solution for some problems with some evidence they have a positive impact, but like so many of the measures already discussed in this section no evidence they impact upon fraud victimisation rates (Cooper et al., 2022).

4. Aims, methods and gap

4.1. Aims and background to research

It is first important to note this research emanates from a research fund from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (Grant number ES/W011085/1) aimed at developing better relations between the UK and South Korea. The theme the authors secured funding under was ageing and technology. Both countries have ageing populations and South Korea is considered be one of the most advanced countries in technological innovation (Dayton, 2020). These countries therefore provided a useful contrast to explore the different measures that have developed to prevent fraud against older adults. The aim of this paper was not comparison, but using these two countries as the starting point to map measures and tools to prevent fraud. As the exercise developed strategies from other countries were noted which were not in use in the UK or South Korea, which were also added to the database. The main aims of this paper were:

•

to map the products and strategies which are used to prevent fraud against older adults (or frauds they frequently are victims of);

•

to secure any evidence that they may work;

•

and to assess their technological development.

4.2. Methods

To achieve these aims a variety of methods were undertaken. First of all, a literature review was conducted seeking research related to fraud prevention specifically for older adults and then more widely relating to prevention directed at frauds that older adults often are victims of. This review noted a wide range of strategies and these were then used to partly populate an Excel sheet of known schemes preventing fraud, with particular reference to older adults. As was noted earlier in the literature review only a small number of studies were found evaluating fraud prevention in general and even less for older adult frauds. The only attempt at mapping a wide range of fraud prevention tools for individual victims was the Button and Cross (2017) study. This literature review confirmed a clear gap in the literature.

Alongside the literature review the researchers visited some of the websites of key organisations working with older adults or the prevention of fraud, such as Age UK, Action Fraud, Cifas to name some. Various Google searches were also conducted using search terms such as ‘fraud prevention’, ‘scam prevention’, ‘phishing prevention’, ‘cybercrime prevention’, ‘call blockers’ etc. Every time a scheme or product was found it was noted in the database with a variety of entries to describe and classify the scheme/product. Particularly for commercial products once a reasonable sample and range were identified no further additions were made. For example, anti-virus products are offered by multiple companies and there was little need in this project to find all providers, rather it was just important to note one as representative of many such products. All distinct products and schemes found were noted in the database. As was established earlier this project started from the basis of exploring the UK and South Korea. The search, however, led the authors to other schemes and products in other countries, particularly the USA which were not found in the two countries. These were also added. In total the researchers identified 106 schemes and products which are directed either specifically at fraud prevention against older adults or a fraud they are victims of in significant numbers. The following results section will explore these schemes and products in more depth.

4.3. Fourth industrial revolution

Before this analysis is presented, however, it is also important to briefly explore the concept of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR). The reason for this is the researchers were particularly interested in the extent to which the technologies associated with 4IR are being applied to fraud prevention. Schwab (2017) argues the first industrial revolution was associated with steam power and mechanisation; followed by the second where electrical power was utilised on a mass scale; and the third industrial revolution which was characterised by electronics and informational technology applied to automation. Building upon the third industrial revolution Schwab (2017) argues there is a 4IR occurring encompassing significant advancements in technology, proceeding at pace, around three broad areas:

●

Physical: autonomous vehicles, 3 d printing, advanced robotics, drones and new materials.

●

Digital: ‘the internet of things’, block-chain, big data, artificial intelligence etc

●

Biological: genetics, synthetic biology (Schwab, 2017).

The researchers were particularly interested, given South Korea is at the forefront of some of these technologies, which of these new and developing technologies were being directed at fraud prevention, particularly older adults (Chung and Kim, 2016). The subsequent analysis therefore also considers the level of technology involved in some of the preventative techniques.

5. The methods of prevention

There have been a variety of attempts at classifying crime prevention, with one of the most famous Clarke's 25 techniques of prevention, which under five broad categories of: increasing the effort, increasing the risk, reducing rewards, reducing provocations and removing excuses unfold another 5 categories each (Smith and Clarke, 2012). Measures found in this research can be mapped into the categories, but many are left blank, such as reducing provocations and assisting compliance, because Clarke's scheme is orientated towards many volume crimes undertaken by opportunistic offenders. While such an approach may work for workplace frauds where there are many potential opportunistic offenders, individual frauds against older adults are often perpetrated by organised crime groups and dogged fraudsters (often based abroad) determined to be successful, so measures which assist compliance are redundant (see Button et al., 2023a, Button et al., 2023b). One of the aims of this project was also to explore technological solutions linked to the 4IR to preventing fraud, so this was an important element in the classification the authors have created.

The sections below explore the variety of schemes and products found preventing frauds against older adults specifically or more generally for frauds they tend to be targeted with. It explores in three parts largely according to the degree of technology utilised before a brief examination of partnership. Some common measures which often illustrate strong resilience to fraud, such as strong family networks were beyond the scope of this research. Included in the table is also a note on evidence of whether they work. As was noted earlier the Maryland scale offers a means to evaluate whether measures have an impact on fraud. Some measures had no such evidence, others had indirect evidence. For example, there have been studies to evaluate whether spam detection works in preventing unwanted emails, but these do not demonstrate whether they reduce fraud – although one could infer that it is likely. These nuances in evidence of whether they work are explored in the figures below. Where there are websites listed in the tables all have been saved at Button et al. (2024) should they no longer be live.

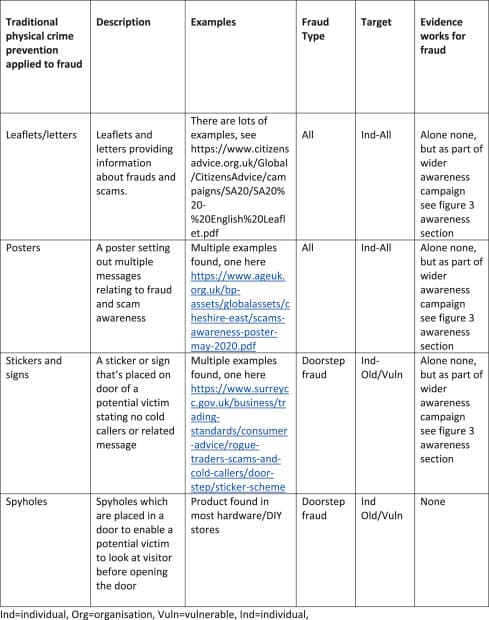

5.1. Traditional products and solutions rooted in traditional crime prevention with limited use of modern technology

The researchers identified a variety of products and schemes which used very little technology and could be considered as rooted largely in the technologies and modus operandi of the first and second revolutions. This included physical products such as stickers, spyholes, awareness raising measures rooted in letters, leaflets and public meetings; and the use of staff who interact with older adults to look out for older adults. These initiatives are very common in more general crime prevention too, such as locks, shutters, awareness through to neighbourhood watch to name some. This section sets out some of these measures applied to frauds against older adults using four sub-divisions: physical crime prevention, traditional crime prevention, awareness raising measures and non-technological applications applied by third parties. Fig. 1 begins this section exploring some of the physical measures which are used of where there is no high quality evidence any of them work.

Fig. 1. Traditional physical crime prevention applied to fraud.

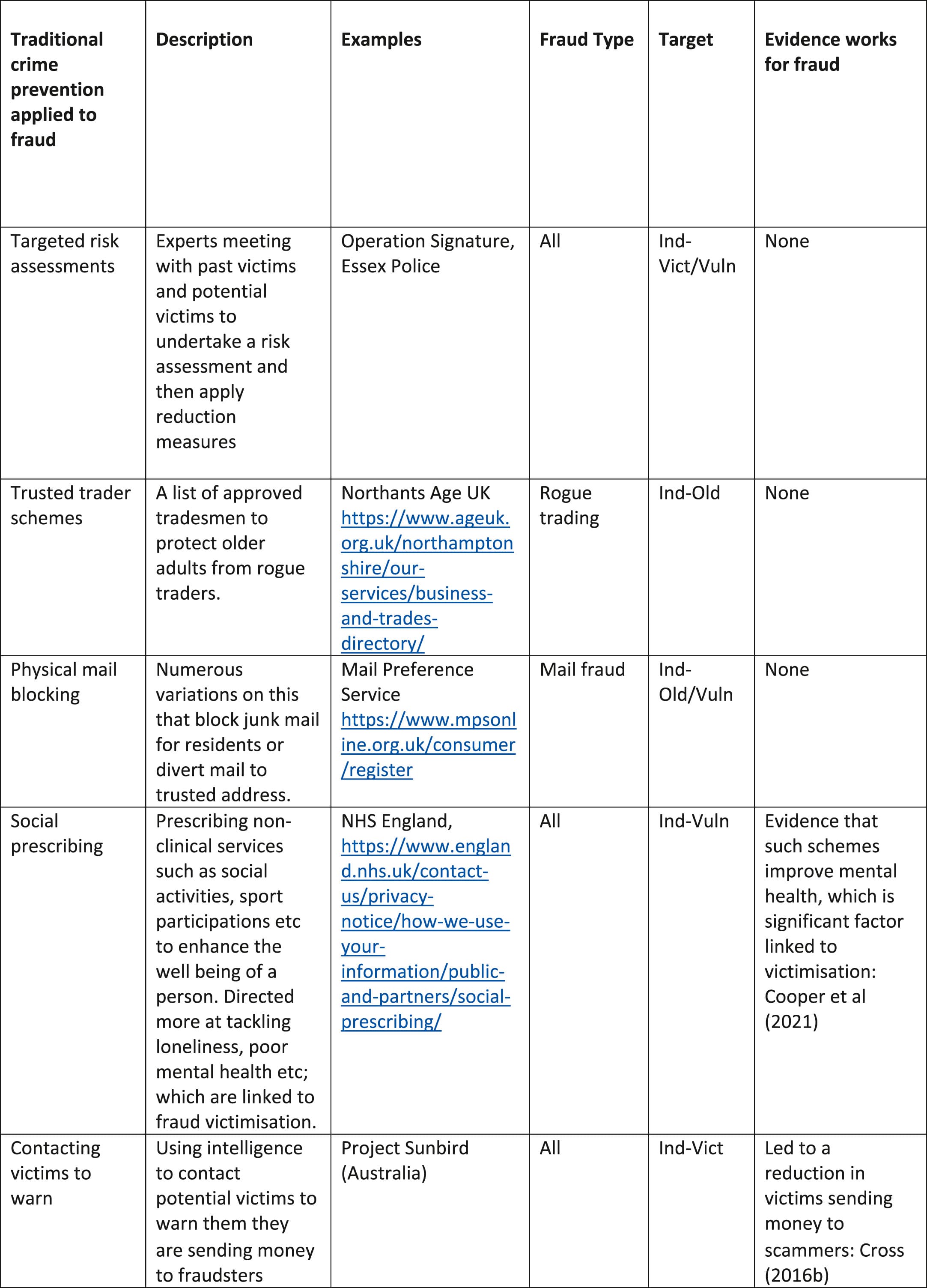

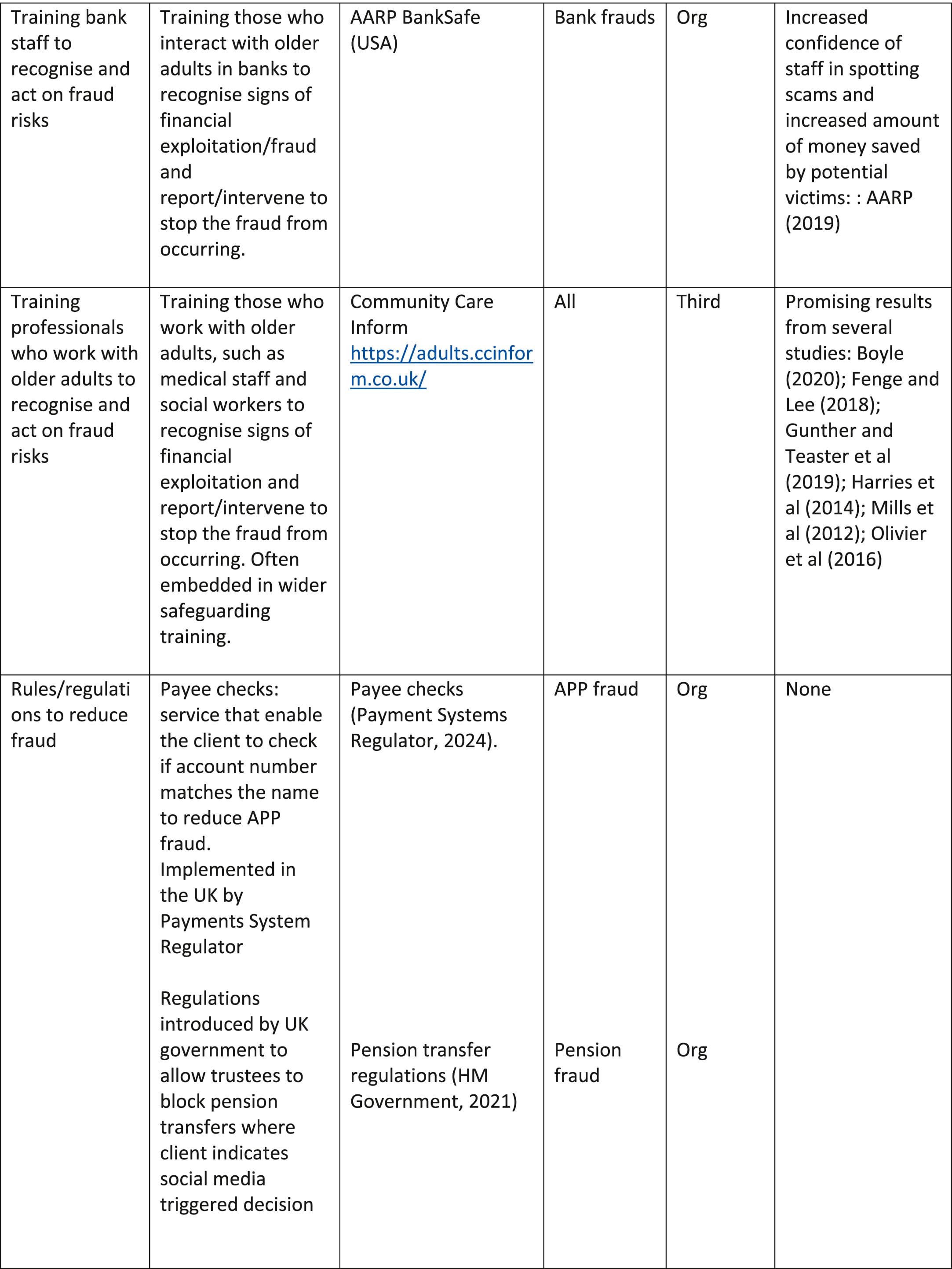

The next set of strategies and tools are also low tech, but not actual physical products in Fig. 2. They include a range of strategies which are used with and by individuals to try and prevent fraud victimisation. Visiting victims and potential victims to conduct a risk assessment relating to fraud and then implement a variety of strategies to reduce the risk is one example of such a scheme. There are also examples of trusted trader schemes where lists of vetted and reputable service providers are provided and then older adults (or others) can choose to use these, reducing the risk of experiencing a rogue trader. Another traditional method is the provision of a service to block junk mail – although this is unlikely to stop determined fraudsters who may secure list of potential victims through other means. There are also services where mail can be redirected so that mail can be vetted. This is usually for older adults who have significant dementia. Also listed is social prescribing which tackles problems such as mental health and isolation, which indirectly – given the links to fraud – provides a form of social crime prevention. With these strategies, other than Project Sunbird and social prescribing there is not much research evidence to show they have a real impact on fraud. This figure also includes some measures discussed earlier which have been evaluated such as warning victims and training bank staff to recognise fraud.

Fig. 2. Traditional crime prevention applied to fraud (Cooper et al., 2022; Cross, 2016b; AARP Public Policy Institute, 2019; Boyle, 2020; Fenge and Lee, 2018; Gunther and Teaster, 2019; Harries et al., 2014; HM Government, 2021; Mills et al., 2012; Oliveria et al., 2016; Payment systems Regulator, 2024).

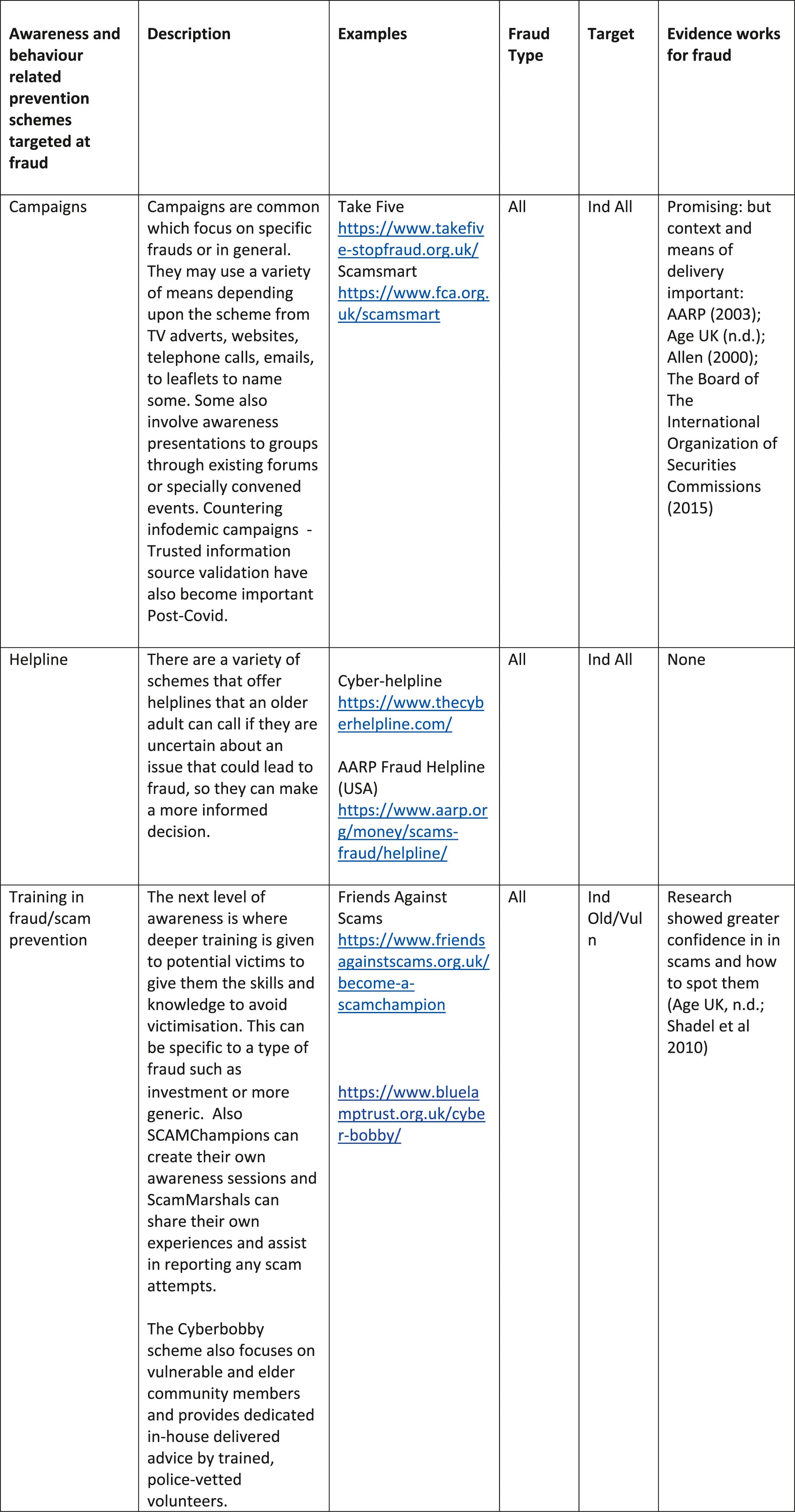

One of the most common forms of methods used to prevent fraud are awareness and behaviour change related schemes. Multiple examples of these were found, with also a much stronger body of research evaluating them. The component parts are listed below, but some of these use overlapping strategies from both Fig. 3 and other figures in this section. Apart from helplines there is a body of research evidence showing positive results (noted earlier), but the context and nature of the delivery is important.

Fig. 3. Awareness and behaviour related prevention schemes targeted at fraud Protection using modern technologies to prevent fraud (AARP, 2003; Abu-Nimeh et al., 2007; Age UK, n.d.; Allen, 2000; The Board of The International Organization of Securities Commissions, 2015; Shadel et al., 2010; Government events, 2021).

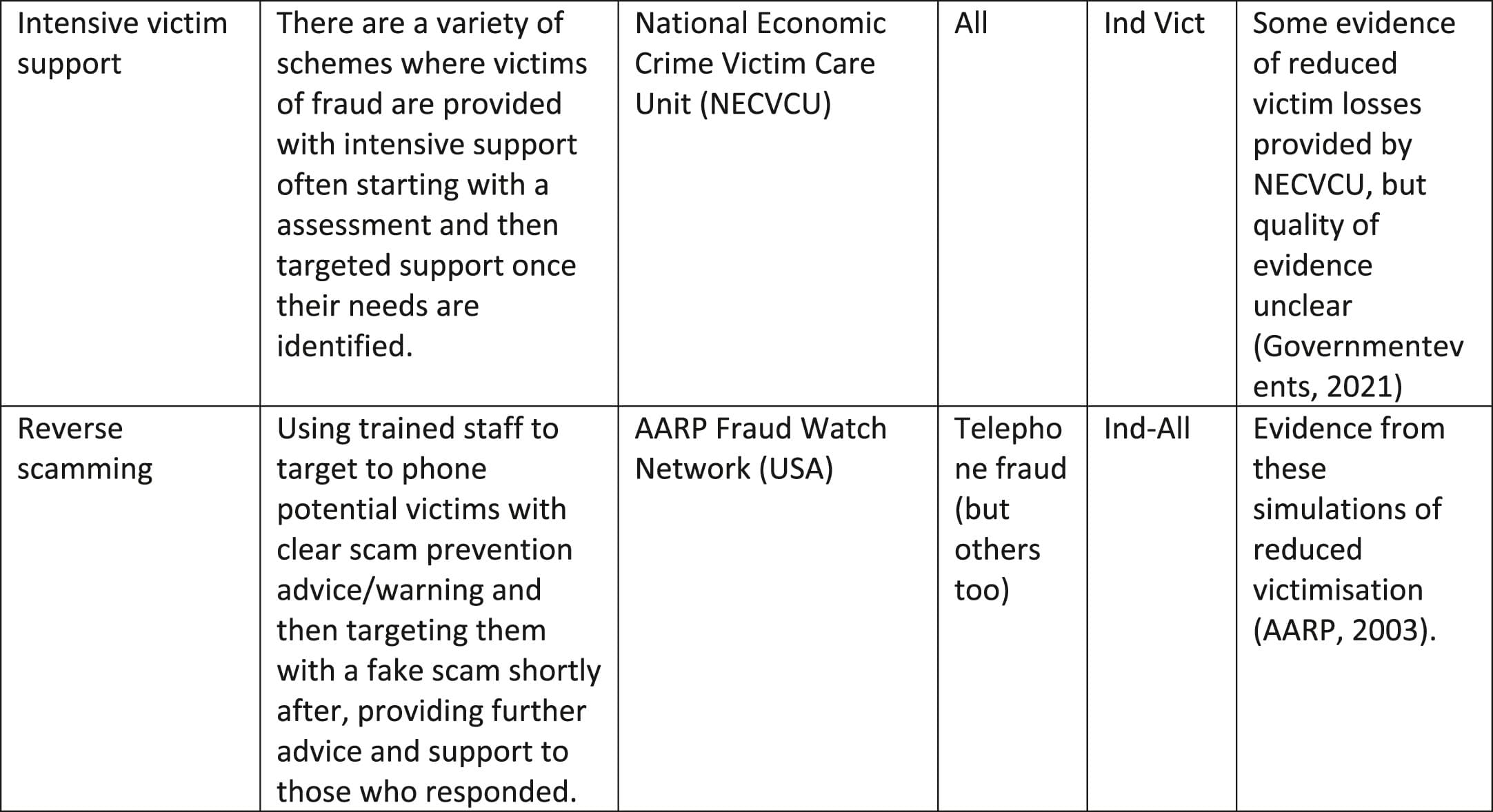

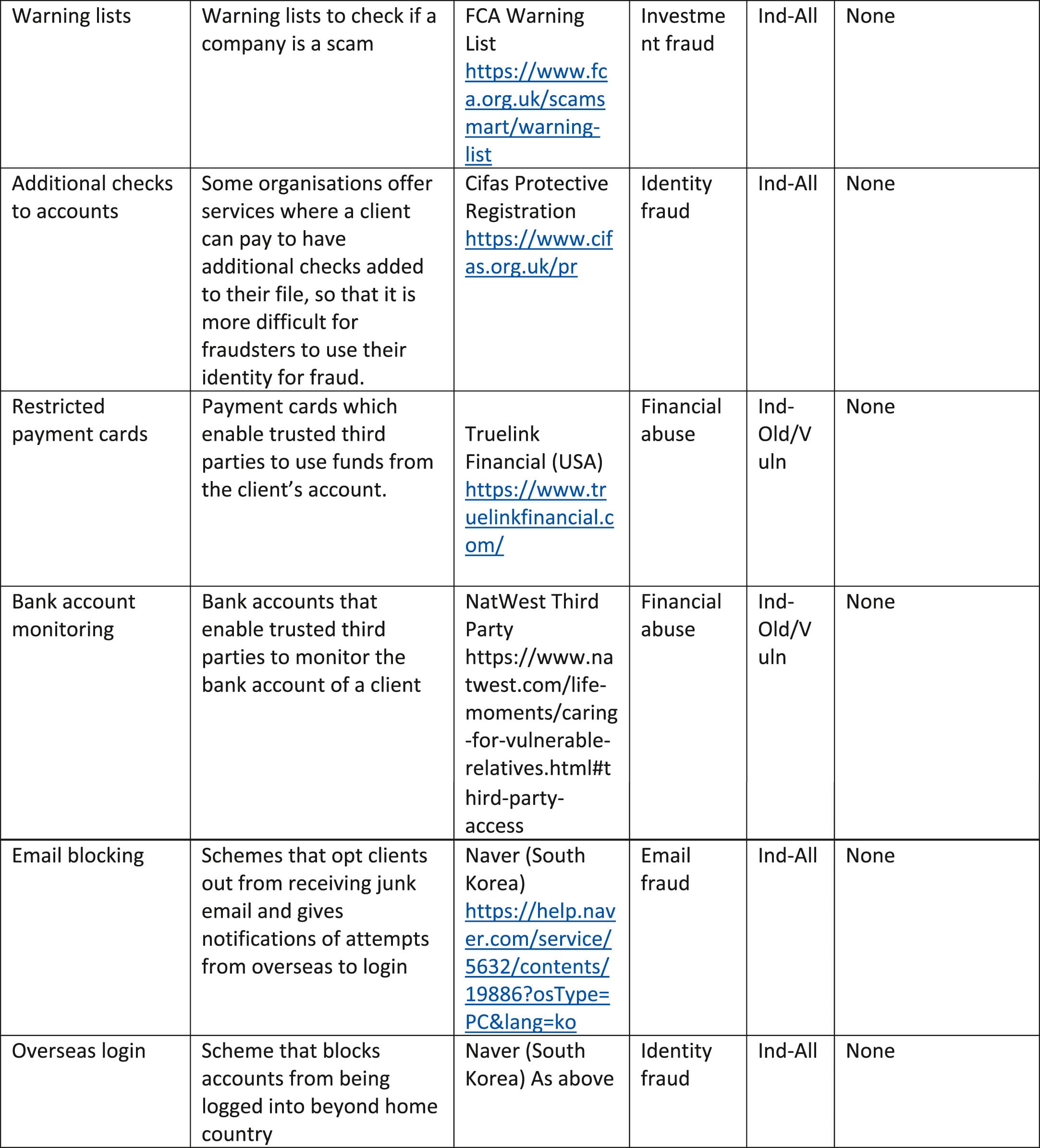

5.2. Protection using modern technologies to prevent fraud

Fraud has also spawned a variety of largely electronic based solutions of varying sophistication to target frauds too. These are based more upon technologies associated largely with the third industrial revolution. They include technologies such as personal alarms linked to communication systems, call blockers rooted in blocking calls not on a customer's list or suspect numbers that have been reported and video door bells. There are also products and services that enable the management of personal data (to reduce identity fraud), services that provide general alerts, warning lists, services that apply additional checks to accounts and payment cards/accounts with built in monitoring restrictions (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Protection using modern technologies to prevent fraud (National Trading Scams Team, 2020; Rosenorn-Lanng and Corbin-Clarke, 2020).

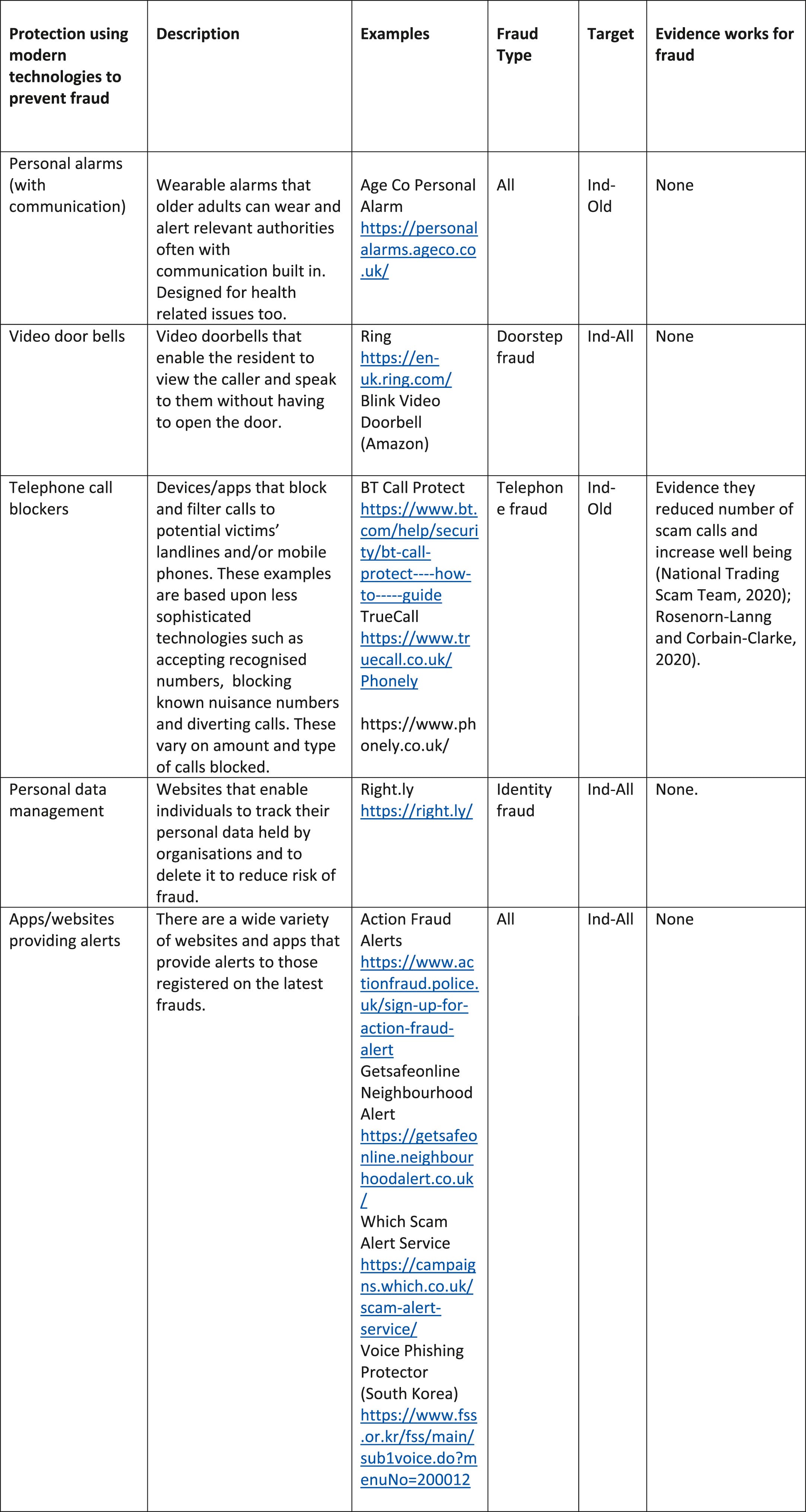

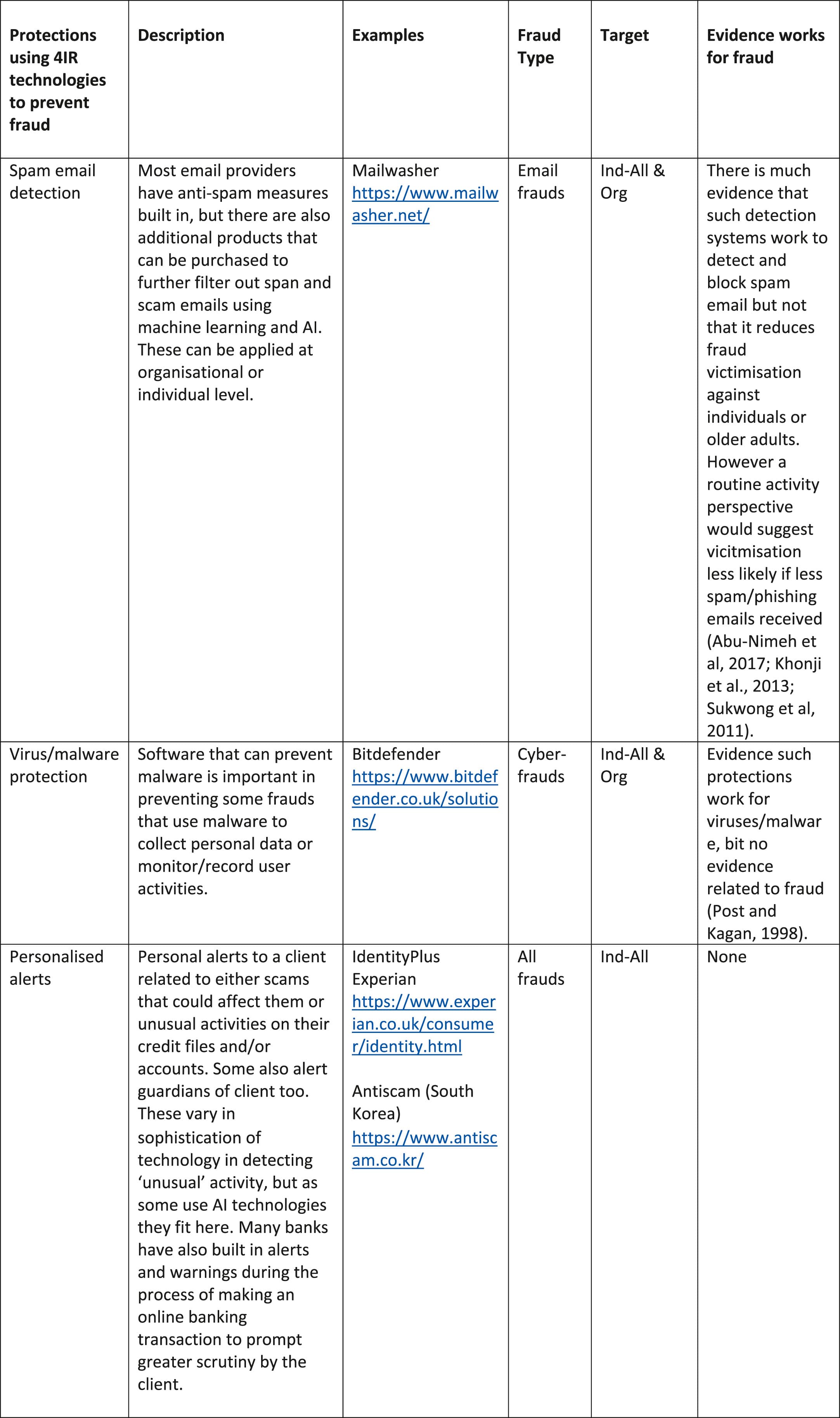

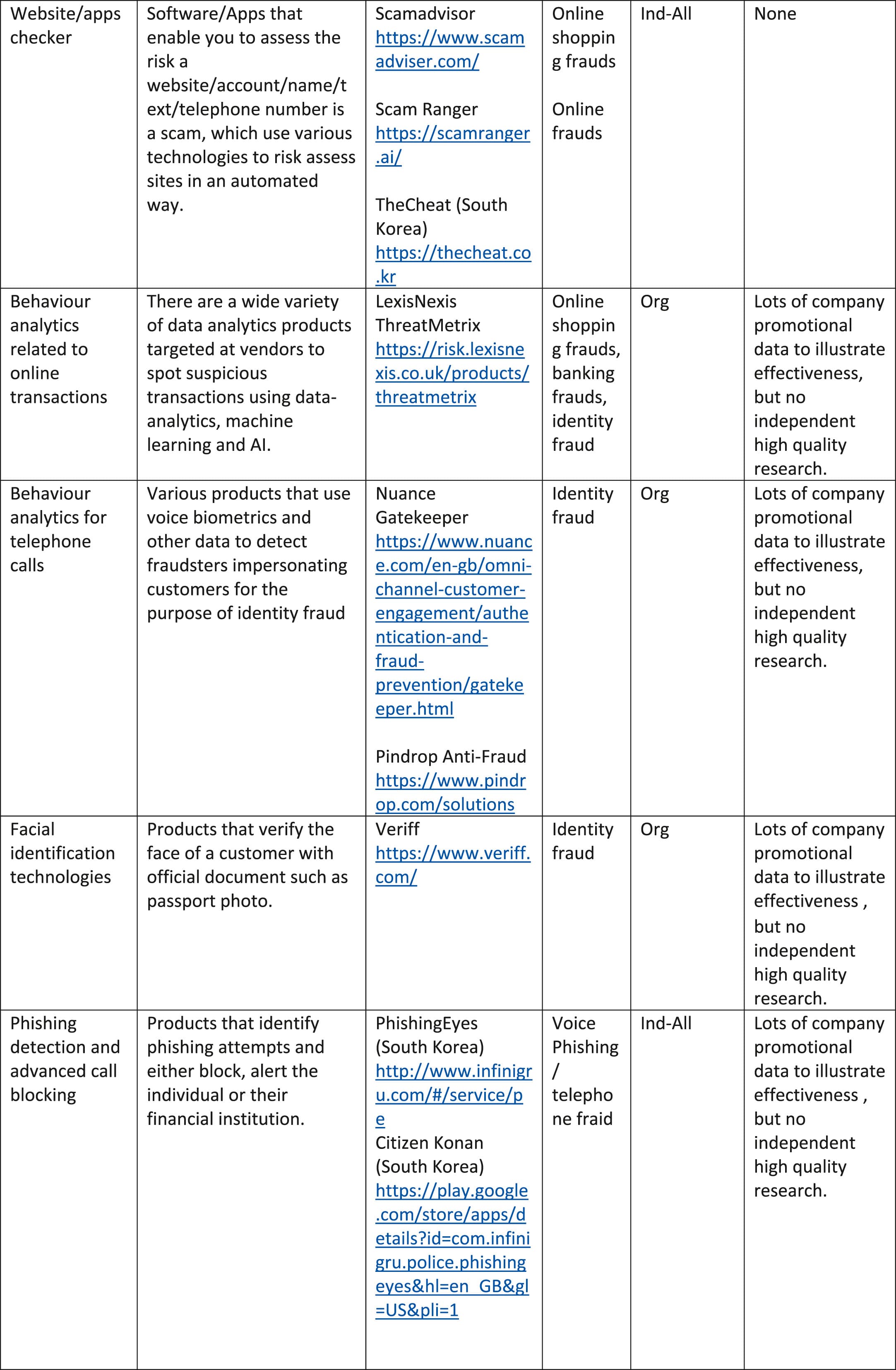

5.3. Protections using 4IR technologies to prevent fraud

The final category covers those products and schemes rooted in technologies associated with the 4IR. The assessment of products and schemes found most of these were rooted in using some of the advancing data-analytics linked to artificial intelligence, big data etc. Some of these are ubiquitous general products targeted at individuals such as spam detection, anti-virus. Others use data to tailor more personalised alerts to individuals. Some of these services are provided by organisations which enable individuals to use, such as Scamadvisor, which is website rooted in sophisticated data analytics to rate the potential risk of fraud of shopping websites. Many of the products are directed at organisations such as banks and retailers and are aimed at using data to protect their clients from frauds such as credit card frauds and identity frauds (see Fig. 5).

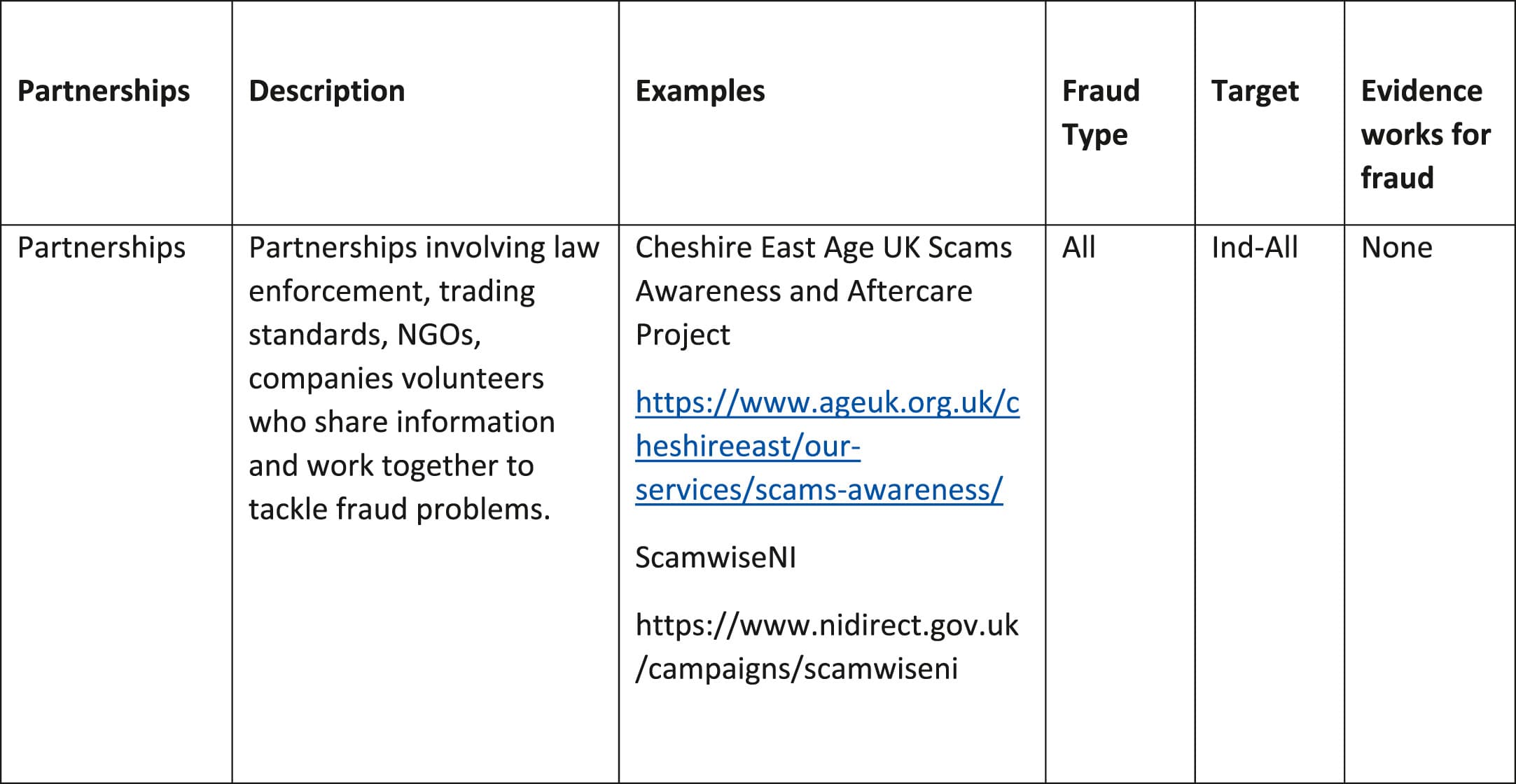

5.4. Partnerships to prevent fraud

Given mainstream crime prevention is dominated by partnerships (Gilling, 2013) it was interesting that very little evidence of strong partnerships to deal with frauds against individuals and older adults was found (Homel and Brown, 2017). A few examples are noted in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5. Protections using 4IR technologies to prevent fraud (Abu-Nimeh et al., 2007; Khonji et al., 2013; Post and Kagan, 1998; Sukwong et al., 2011).

Fig. 6. Partnerships to prevent fraud.

6. Towards a holistic prevention model

This paper has identified some of the many strategies and tools which are used to prevent frauds that older adults are frequently victims of the paper has also explored any evidence of their effectiveness and in doing so highlighted there is a lack of high quality evaluations that meet Maryland level standards. Instead there are some tools and strategies with no evidence at all that they work and others with indirect evidence, such as strategies which stop linkages between offender and victim, such as call blockers and anti-spam detection systems, but which still lack evidence of impact on fraud victimisation against older adults. Evaluation is not the only research gap, there is also little evidence of the extent to which some of these different measures are used.

An important question that arises is do we need to know to a very high standard if something works? The answer has to be ideally yes, but quality evaluations cost money and fraud is rarely an issue that has abundant funding. Having a body of evidence as to whether measures work, even if weak is better than nothing. There are also theoretical observations that can be made, such as routine activity theory, to develop prevention strategies with some confidence. Nevertheless, it is important more work on evaluation is undertaken and as strategies are proven or unproven and then strategies that are applied are adapted according to this.

This paper has also highlighted the technological basis of different measures and products. It has shown a dominance of activities rooted in traditional crime prevention techniques and low tech. Evidence of high technology solutions rooted in the 4IR were found in both the UK, South Korea and other countries. Again, the extent of their use is difficult to determine, but there would clearly be more scope for products and services to embrace 4IR. There are also opportunities for more debatable practices to be considered such as reverse scamming to identify high risk individuals and then work with them.

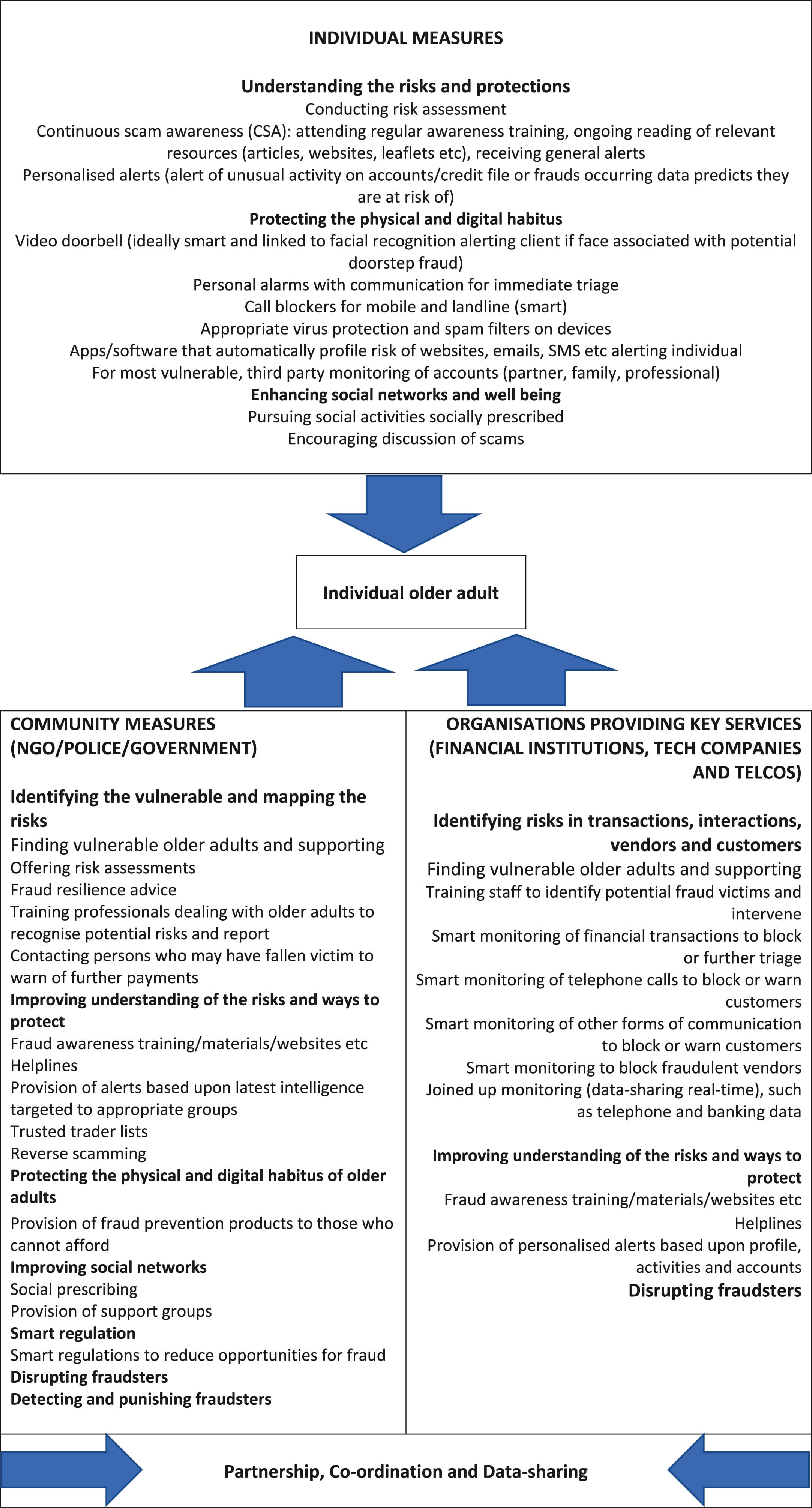

Drawing upon the analysis of strategies leads us to propose the following holistic prevention model for older adults (see Fig. 7). The absence of extensive high quality evidence strategies and tools work has led us to add all of them into this model, but grouped under specific targets for action: the individual, government/law enforcement and organisational context. It also identifies where the basic building blocks of 4IR could be applied to produce even more effective tools and services. Such is the diversity and extent of different measures we do not claim the totality of measures or identify all the 4IR opportunities, but we are confident of noting the most important. We use an example of an older adult living alone with limited use of modern technology such as online shopping and banking, but this could be adapted for other types of individual. It sets out an ideal approach and identifies potential solutions not yet been delivered, but where there is the potential with technology to develop. The model is divided into four parts centred on the potential older adult.

Fig. 7. The older adults holistic prevention model.

The first focuses upon individual older adults and the starting point is understanding risks and protections. The individual alone – using appropriate resources or with the help of a professional should conduct a risk assessment related to frauds and scams. They should engage in Continuous Scam Awareness (CSA) by attending relevant training, reading appropriate materials in leaflets, websites etc of appropriate bodies and they should receive alerts on the latest scams. More personalised alerts should also be pursued suited to the individual's needs and activities. These already exist for paying customers in relation to mobile phone calls, emails, credit files and financial transactions. But there are opportunities to develop these even further by relevant bodies sharing data, utilising AI and tailoring to individuals (see third part of model). So, for example in the future emerging intelligence of a particular investment scam, could be addressed by warnings which could be disseminated to those who are most likely to buy such investments based upon AI. Another example could be a person online shopping and they visit a website and are notified this is a high risk of scam as soon as they arrive.

The second part of the model is protecting the physical and digital habitus of the older adult. Many of these products already exist, but there is also the potential to further enhance with technology. A video doorbell for example could be further enhanced to conduct facial recognition of a visitor or assess their identify card to check their validity. There are already facial recognition services for retailers to deal with shoplifters (see https://www.facewatch.co.uk/facial-recognition-for-retail-sector/ ), so an offender who defrauded an older adult on the doorstep, whose image is captured could be placed on the system. Their face could then automatically trigger a warning and even a call to the police. Wearable personal alarms which are used for health and safety reasons too, could also aid protection. For the very vulnerable such devices could transmit audio conversations which are analysed by AI for phrases in conversations which could be a risk, triggering a response.

Call blockers have been discussed above and clearly have a use, but they could be even smarter. The movement to digital landlines and greater use of mobile provides much more opportunity for applications to block/warn calls based upon AI based data analysis. The scope for conversations to be monitored too with trigger phrases prompting warnings and/or termination of a call or intervention of a trusted third party. Communication has also become much more diverse with systems like Zoom, Whatsapp etc and these need to be covered too. Anti-virus and spam filters are already very advanced and it is important older adults have these too and are up-to-date when they use such technologies. Encouraging the use of websites such as Scamadvisor and developing these to the next level so the analysis is automated and covers other services is another opportunity. For the most vulnerable in society, such as those suffering significant cognitive decline third party (partner, family, friends, professionals) monitoring and control of accounts is an important tool.

Finally, individuals who are alone or lonely – given the risk this creates for fraud – should be encouraged and helped to participate in social events. They should also be encouraged to discuss concerns within their social networks related to scams and particularly any unusual approaches they may have received. Taken together these provide for a well protected individual, but there are other important parts to the model.

The second part of the model is the role of community through the police, NGOs and the government. The activities proposed in this part vary in who has responsibility in different countries, but whoever is responsible these are the important elements. It is important to understand in a community who are the vulnerable who might fall for frauds and understand the risks. Agencies need to find these people and work with them. Some will not know how to do a risk assessment and this is where agencies can help too in advising on appropriate measures to reduce risks. Earlier it was noted the importance of training individuals who work with older adults to spot signs of vulnerability and report and this is an important part of this process. Cross's (2016b) research illustrates how important it is to also alert potential victims and the intelligence gathered by agencies can be used to do this when evidence meets appropriate thresholds.

Another aspect of this model is improving the understanding of the risks and ways to protect. Central to this is fraud awareness training utilising actual training, presentations, websites, leaflets, videos etc. It is important the advice is appropriate and tailored to the appropriate demographics. Generic (and where possible tailored) alerts of emerging frauds should also be provided based upon the latest intelligence. Lists of traders who meet certain standards should also be disseminated to older adults to make informed choices and those lists should be policed so unethical behaviours lead to removal. More controversially it might be appropriate to reverse scam in certain contexts to find those more at risk and then try and work with them. Agencies can also try to help individuals enhance their physical and digital habitus. The resources of older adults vary and some will need help to purchase products to protect them such as call blockers, video doorbells etc.

Communities should also work together to support social activities (subsidizing where appropriate) and provide social prescribing services. Governments and other relevant bodies should also pursue regulations which reduce fraud risks. The final part has not really been the focus of this article, but it would be wrong to not note strategies such as disrupting fraudsters (closing websites, bank accounts etc) and catching and then applying appropriate sanctions after prosecution to aid specific and general deterrence.

The third part of the model related to the companies that provide services which are used for frauds, most notably the financial institutions, telcos and tech companies. The research for this paper revealed many initiatives already occurring to reduce fraud and therefore is so much more potential for these companies to protect their customers from fraud. As with communities the starting point has to be the finding of vulnerable clients, which can be done through a variety of means. An important element of this for the banks is educating staff who deal with customers to intervene – as noted earlier a proven strategy (AARP Public Policy Institute, 2019). There are then, in these types of companies multiple opportunities to use data and AI to identify risky transactions, interactions, customers and vendors. These can be used to block and warn, sometimes not even involving the customer and potential victim – creating unseen protection. Much of this is already occurring, but more could happen, such as sharing of data on vulnerable older adults. For example, if banks had real-time access to mobile phone or internet activity of a client this could be very useful. A customer who is trying to pay a new person who at the same-time or hours before has been on a phone-call with a number the telco deems high risk, should provoke an intervention from the bank. There are of course huge privacy implications, but the potential of data-sharing with AI is huge. Like the second part of the model dedicated at community measures there is also scope for companies to also improve understanding of the risks and to disrupt fraudsters.

The final part of the model advocates partnership, co-ordination and data-sharing between the organisations in the community and private entities. This research has uncovered multiple agencies doing work to prevent fraud against older adults. In the UK this includes the many police forces, local authority trading standards departments, social work departments, healthcare providers, NGOs like Cifas, UK finance, Age UK and Reengage, many banks, tech companies and Telcos to name some. There is limited national and local level partnerships, data-sharing and co-ordination. There are often slightly different messages in awareness campaigns, different approaches and lack of data-sharing, with organisations working alone in a silo or small group of silos. If a bank identified a vulnerable client, it would be highly beneficial to share that data with other appropriate agencies, so the police or NGO visit undertake a risk assessment, provide awareness and training and relevant products and other companies are alerted to the risk with this person. Campaigns and guidance should be similar and co-ordinated. So central to the success of this model are also structures that facilitate greater partnership and a national and local level, which then lead to greater co-ordination and data-sharing.

7. Implications and limitations

It is important to note the limitations of this research. Noted throughout this paper is the lack of high quality evidence of whether tools and strategies work in preventing fraud in general and against older adults in-particular. An extreme perspective could have been if there is no evidence they work, don't recommend them. This would have left a very thin number of strategies. In the absence of this evidence base the authors have tried to bring all of the strategies together targeting the three key areas: individual, community and organisations. The authors are firmly of the belief it is better to do this than advocate only those that have been proven to work because of the importance of protecting this group. The implications of the findings from this paper and the model are the need for much more research and evaluation of the different measures used to prevent fraud, using high quality methodologies. As this is the first paper the authors are aware of linking all available strategies together, another implication is to expose practitioners to the diversity of tools they can use. It is highly likely many practitioners do not know the full tool-box available. The final implication is the finding of limited use of the latest technologies associated with 4IR. This paper has identified some areas where greater innovation could be applied. There are likely to be many more. Much more investment in technical innovations applied to the problem of fraud against older adults needs to be explored, developed and evaluated.

8. Conclusion

This paper has explored the prevention of fraud against older adults. The paper began by illustrating the scale, challenge and impact of fraud on older adults. The small research base of studies that have evaluated fraud prevention measures either directed at older adults or for frauds they tend to be victims of, was then considered. After outlining the methodology of the paper it then set out the first comprehensive assessment of the many tools and strategies used to prevent frauds that older adults are often victims of along with any evidence if they work and their degree of technical sophistication. From the many tools and strategies identified this paper they were then linked together to produce a holistic prevention model for preventing fraud against older adults rooted in three key parts: the individuals themselves, their communities and the companies that provide services to them which are conduits for fraud. This model is not set in stone and as new strategies and technologies emerge it should be adapted, particularly where high quality evidence of effectiveness emerges. Measures that work should become more prominent and those that don't should be dropped. The model will be useful to law enforcement, those agencies working with older adults and policy-makers, as well as companies offering services to older adults where frauds occur (banks, telcos etc) and those developing tools to tackle this fraud. The evidence is fraud is growing and in ageing societies the number of older adults is getting bigger. It is vital adequate prevention is applied to protect these (and all) citizens.