Abstract

Objective: People who are incarcerated experience social exclusion and have higher rates of mental and substance use disorders than the general population. Prisons are not suitable for treating mental illness, and understanding how the profile of prison populations changes provides essential information for correctional service planning. This study examined changes in the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders among people admitted to provincial prisons in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods: The study included all people admitted to any of the 10 provincial prisons in BC from 2009 through 2017 (N=47,117). Using the Jail Screening Assessment Tool, a validated intake screening tool designed for rapid identification of mental health needs, the authors calculated the period prevalence (by calendar year) of mental health needs, substance use disorders, and drug use.

Results: The proportion of people with co-occurring mental health needs and substance use disorders increased markedly per year, from 15% in 2009 to 32% in 2017. Prevalence of methamphetamine use disorder increased nearly fivefold, from 6% to 29%, and heroin use disorder increased from 11% to 26%. The proportion of people with any mental health need and/or substance use disorder increased from 61% to 75%.

Conclusion: The clinical profile of people admitted to BC prisons has changed, with dramatic increases in the proportion of people with co-occurring disorders and reported methamphetamine use. More treatment and efforts to address social and structural inequities for people with complex clinical profiles are required in the community to reduce incarceration among people with multifaceted and complex mental health care needs.

HIGHLIGHTS

The proportion of people admitted to prison with co-occurring disorders (i.e., mental health needs and substance use disorder) steadily increased between 2009 and 2017.

The percentage of people admitted to prison with methamphetamine use disorder and heroin use disorder increased, while the percentage of people with cocaine use disorder decreased.

Detailed intake screening records provide a rich, consistent source of data that can be used to understand the population-level health needs of people who experience incarceration and to strengthen systems-level reform efforts.

Further research is required to understand the extent to which poor access to appropriate health care services in the community contributes to elevated rates of mental health needs and substance use disorders among people who experience incarceration.

People with mental and substance use disorders are overrepresented in the carceral system, and this circumstance appears to be a global phenomenon. Systematic reviews have found elevated rates of major depression, psychosis (1, 2), and substance use disorders (3, 4) in prisons compared with the general population. In the United States, prevalence estimates of mental illness in prison range from three to 12 times higher than in community samples (5). People with mental disorders are held in prison longer than those without these conditions, despite being charged with similar offenses (6), and substance use is strongly associated with being repeatedly incarcerated (7). The elevated prevalence of mental and substance use disorders in prisons has been variously attributed to the War on Drugs political initiative, the criminalization of mental illness, and insufficient community-based mental health resources (8, 9).

There is reason to believe that the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders is changing within prison populations. The international prison population grew by 20% between 2002 and 2020 (10), and the United States is at the forefront of that growth, reporting a 500% increase in the prison population over 40 years (11). This massive growth has been attributed to increasingly harsh sanctions and sentencing law rather than to increases in crime (12). The ethnic, gender, and age distributions of people in U.S. and Canadian federal prisons has also changed dramatically (13, 14). At the same time, the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders has changed at the population level. For example, national survey data have shown broadly worsening mental health across the United States and Canada, with significant increases in depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts since the early 2000s (15–18). Since 2016, North America has experienced unprecedented substance-related deaths primarily due to fentanyl contamination in the drug supply (19). Given the changes in prison admission rates and the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders, updated and reliable monitoring of these conditions among people who experience incarceration is imperative.

The health of people in prisons is an underresearched area generally, and trends in the prevalence of mental and substance use disorders are particularly understudied. Most prison-based prevalence studies use a cross-sectional design and do not inform trends over time (e.g., 20–22). With the available research, it is difficult to determine whether more people with these conditions are being identified because of changes to intake screening or because the true prevalence of mental and substance use disorders among people in prison is increasing (23). We found only one longitudinal study, Bradley-Engen et al. (9), which examined trends in prevalence of serious mental disorders (major depression, bipolar, and psychotic disorders) and co-occurring disorders in Washington State prisons from 1998 to 2006. The authors reported no increase in psychotic disorders, but a significant increase in comorbid substance abuse. Given substantial changes in the epidemiology of mental and substance use disorders in North America since this study was published, more recent data are needed.

For people with mental and substance use disorders who face entrenched social and economic hardships, incarceration may represent the first opportunity for assessment and treatment of illness (5). Reliable prison intake screening and/or assessment data are critical to accurately estimate the prevalence of illness within this marginalized group (24). The current study examined trends in the prevalence of mental health needs and substance use disorders among all adults who experienced incarceration in British Columbia (BC), Canada, over a 9-year period.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in BC, the most westerly province in Canada, with administrative data collected at intake by BC Corrections mental health screeners across all provincial prisons. The study included 10 facilities, which are also responsible for pretrial custody, bail and remand, and sentences less than 2 years.

Data Sources

The primary data source for mental health intake information in the BC correctional system is the Jail Screening Assessment Tool (JSAT) (25). The JSAT is a validated (26) structured professional judgment tool that screens for mental health and management needs and takes approximately 20 minutes to complete. The JSAT responses have been stored electronically since 2007 in BC, and both the tool and training to use it remained consistent throughout the study period. Trained mental health screeners complete the JSAT interview during every prison admission. Consistent with the JSAT manual (25) and general screening guidelines (e.g., National Commission on Correctional Health Care [27]), the interviews are conducted within 24 hours of a client’s reception to a facility. Data are entered into an electronic medical record housed on the Primary Assessment and Care databases of the Ministry of Justice, Corrections Branch.

Criminal justice information for each client was obtained from BC Correction’s CORNET (Corrections Operations Network). CORNET is the Corrections Branch’s electronic platform used for the administration of sentences and supervision, and it is the primary repository for all data relating to an individual’s involvement with corrections. CORNET data were used to verify the dates of admission to and release from custody, details of the admission (e.g., new offense, breach, transfer), release codes (e.g., released to bail, sentence end), and custody status (e.g., remand, sentenced). The JSAT is conducted for all admissions, including new admissions, transfers from other facilities and hospitals, and intermittent moves. The JSAT and CORNET admission files were linked deterministically by using unique client IDs. The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioral Research Ethics Board and Simon Fraser University Research Ethics Board (REB H17–02653).

Sample and Exclusions

We accessed data on admissions to all 10 BC provincial prisons between January 1, 2009, and September 30, 2017. This end date was selected because on October 1, 2017, the provincial health authority assumed responsibility for health care service delivery in prisons in BC. This major province-wide policy change may have had implications for health services and health screening in BC prisons. Records with missing age and/or sex of the client were removed. If two records had the same client ID and date of admission, the record with the most missing data was removed (keeping only one record per person on any given day). Duplication of records may have occurred because the screener needed to conduct the interview in multiple sessions (e.g., if the client was experiencing high distress or deterioration or if there was an emergency in the center). We reported annual prevalence estimates and therefore allowed each person to enter the sample only once per year. In line with JSAT guidelines that recommend the interview take place within 24 hours of an admission, we identified a corresponding JSAT record by using the CORNET admission date. When an individual’s stay in custody is <24 hours, the JSAT may not be completed. We excluded JSAT records without a corresponding CORNET record for a new admission within a 2-day window preceding the date of the JSAT interview (see the figure in the online supplement to this article for details on exclusions). All sections of the JSAT used in this study had <1% missing data.

Measures

Jail screening assessment tool.

The JSAT interview solicits information pertaining to clients’ past and present sociodemographic characteristics and social background, present legal circumstances, history of criminal justice involvement and violence, history of mental disorders and mental health treatment, substance use, past and present suicide and self-harm issues, and acute psychiatric symptoms (28). The mental health screener uses structured professional judgment to determine risks and needs and makes management recommendations.

Ascertaining mental health needs and substance use disorders.

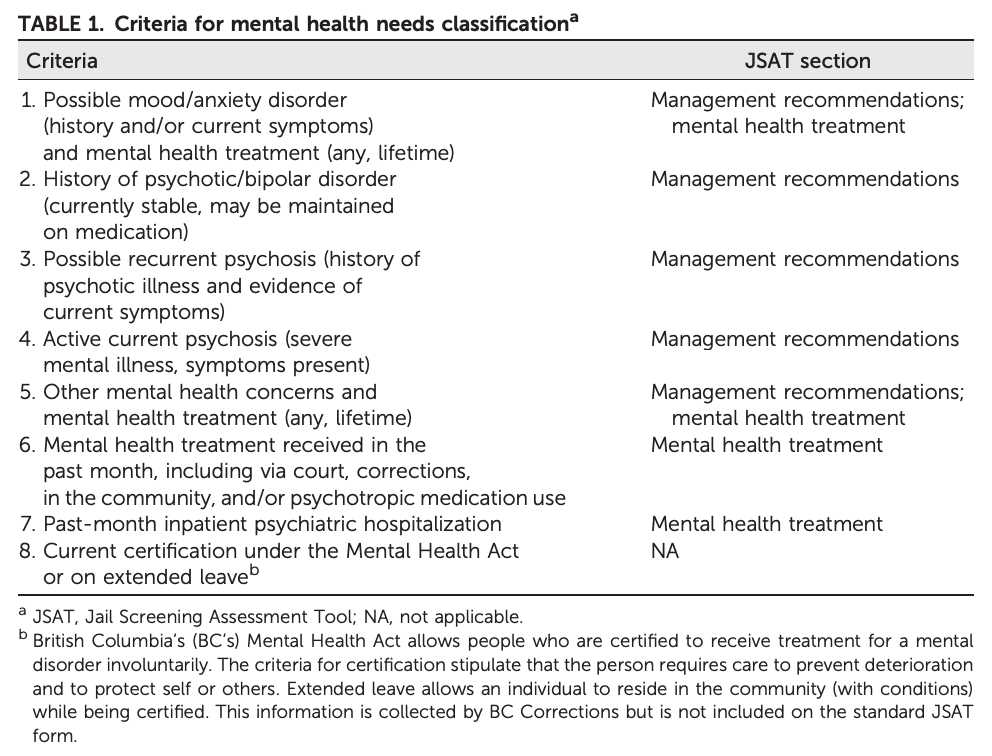

We created four mutually exclusive categories for mental and substance use disorders: mental health needs only, substance use disorder only, co-occurring disorders, and no disorder. Each JSAT record was coded as one of these four diagnostic categories. An individual’s diagnostic category could change over time if the person had more than one admission. Criteria were developed in collaboration with clinical experts with experience conducting the JSAT interview and training interviewers.

Mental health needs were determined by using a combination of reported history of mental health treatment and needs identified within the Mental Health Treatment and the Management Recommendations sections of the JSAT. We categorized people into the mental health needs group if any of the eight criteria in Table 1 were met.

We categorized people into the substance use disorder group if current abuse or long-term severe abuse in any of the six drug categories—alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, methamphetamine, and other drugs—were indicated (see the online supplement for detailed JSAT coding guidelines). A person was classified as having co-occurring disorders if both the mental health needs and substance use disorder criteria were met on the same record.

Sociodemographic variables.

Sociodemographic variables included age; sex (male or female); identifying as Indigenous; education (less than high school, high school, university/vocational); a measure for homelessness or unstable housing, whereby responses of anyone who reported being homeless or living in a hotel or with friends (not paying rent) at the time of admission were coded as “yes” and other responses as “no”; and receiving social assistance or disability payments (yes or no).

Drug use patterns.

We created a variable for each drug, whereby current abuse or long-term severe abuse for each drug type was coded as 1 (otherwise coded 0).

Analyses.

We calculated the annual period prevalence of each measure by using the total number of first-time admissions per year, an unduplicated count of people admitted in that calendar year, as the denominator. We examined differences between 2009 and 2017 by using Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables and Welch two-sample t tests for continuous variables. In large samples (such as ours) p values quickly go to zero, and, therefore, conclusions based on significance alone are meaningless unless they are interpreted in light of the magnitude of the effect size (29). We calculated the effect sizes to examine the strength of the associations by using Cramér’s V for the chi-square estimates and Cohen’s d for the t test. A Cramér's V of 0.1 provides a minimum threshold suggesting a substantive relationship between two variables; a result of 0.2–0.3 is considered moderately strong, and ≥0.3 is considered strong (30). The conventional frame of reference for Cohen’s d is that 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 correspond to small, moderate, and strong effect sizes, respectively. All analyses were performed in R, version 3.6.1, by using the dplyr, ggplot2, rcompanion, and rstatix packages.

Results

A total of 148,188 JSAT records were completed between January 1, 2009, and September 30, 2017, including all admission types and transfers. Of those, 141,489 (95.5%) had a corresponding corrections record indicating a new admission to custody within the previous 2 days.

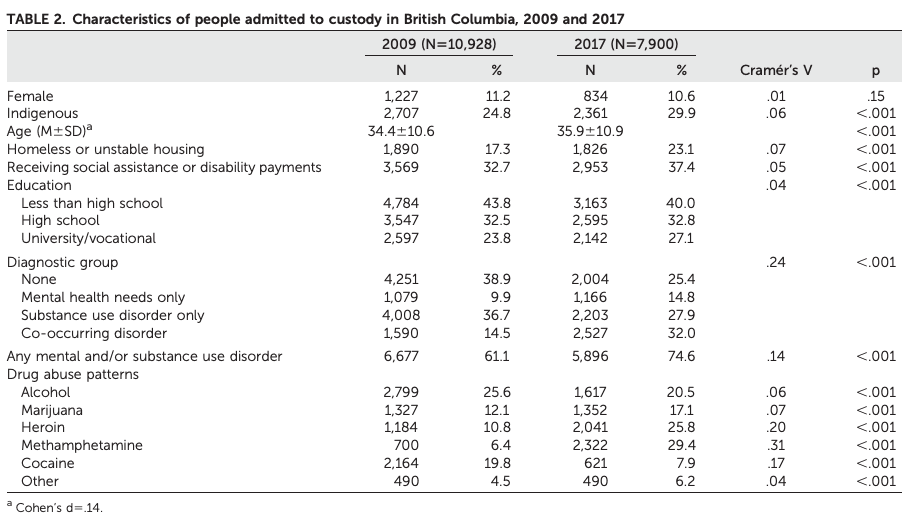

After we removed readmissions within each calendar year, the total count over the study period was 91,938 admissions among 47,117 unique individuals. Changes in the profile of people admitted in 2009 and 2017 were statistically significant for all variables except sex (Table 2). A moderately strong effect was found for changes in mental and substance use disorders status (Cramér’s V=0.24) and changes in heroin use disorder (Cramér’s V=0.20), and a strong effect was found for changes in methamphetamine use disorder (Cramér’s V=0.31). All other effect sizes were small.

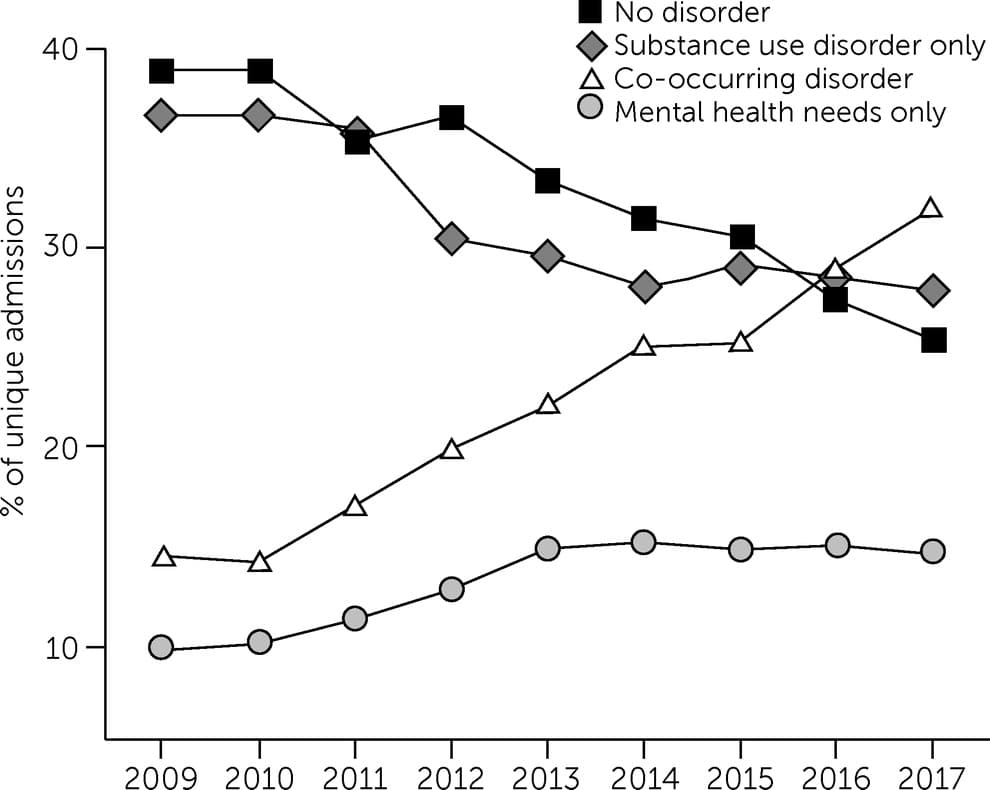

The prevalence of individuals with mental and/or substance use disorders changed considerably between 2009 and 2017. The percentage of admissions of clients with no disorders fell from 38.9% to 25.4%. The percentage of people with co-occurring disorders more than doubled, from 14.5% to 32.0%. The percentage reporting mental health needs alone rose from 9.9% to 14.8%. Finally, the percentage with substance use disorder alone dropped from 36.7% to 27.9% (Figure 1 and Table 2).

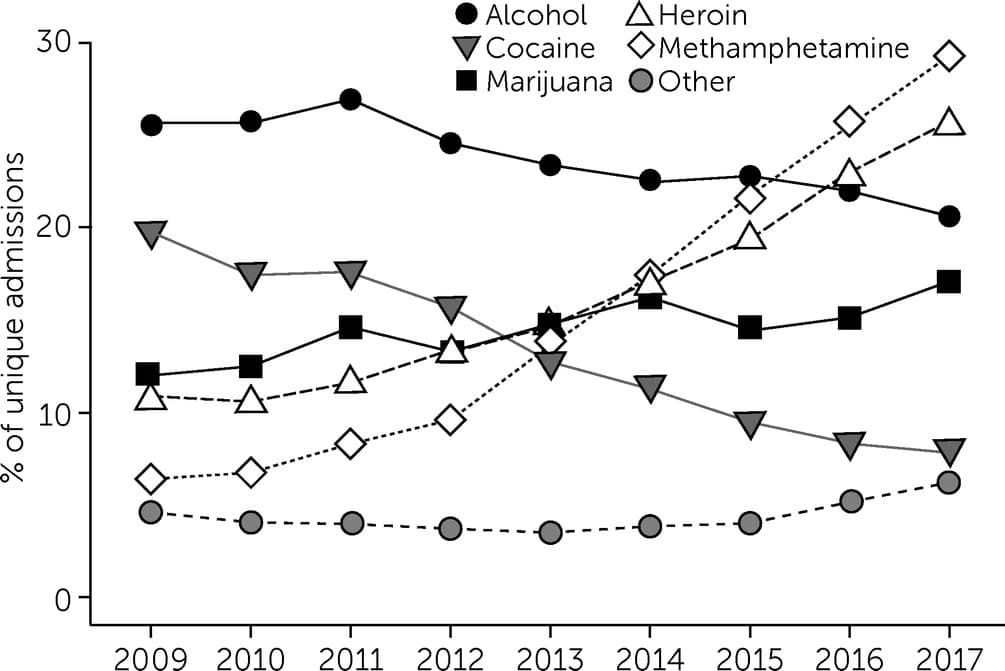

The percentage of people reporting alcohol use disorder decreased slightly from 25.6% to 20.5%. The percentage of people with heroin and methamphetamine use disorder rose from 10.8% to 25.8% and 6.4% to 29.4%, respectively. The percentage of people identified as having cocaine use disorder decreased by 11.9 percentage points (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Discussion

Analyzing population-level cohort over 9 years, we found that the proportion of people entering prisons with any mental health need and/or substance use disorder rose steadily, driven largely by a marked 121% increase in co-occurring disorders. Nearly one-third (32.0%) of people admitted to custody in 2017 met the criteria for having a co-occurring disorder, representing the most prevalent diagnostic subgroup among people admitted that year, followed by people with a substance use disorder alone. The prevalence of co-occurring disorders in the community is considerably lower; national estimates in Canada and the United States range from 2% to 4% (31, 32). The elevated and increasing rate of co-occurring disorders is of particular concern given that comorbid conditions tend to result in worse health and criminal justice outcomes than any single condition (7, 33, 34).

These trends may reflect the availability and adequacy of care provided in the community. Treatment services often lack sufficient expertise and resources to treat co-occurring conditions, and sequential or parallel treatment for mental and substance use disorders has generally been shown to have poor outcomes (35). Historically, mental disorders and substance use disorders have been treated in separate service systems with differing and sometimes contradictory philosophical orientations (36). An integrated treatment approach was developed in the late 1980s in the United States (37), but the evidence in favor of the integrated model compared with other treatment modalities remains equivocal (38). However, integrated primary care models for people with high-severity disorders may improve symptoms, patient satisfaction, and posttreatment mental and substance use disorder outcomes (39–41). More research is needed to understand the types of co-occurring disorders that can be treated effectively with single-disorder interventions and those that require integrated mental health and substance use disorder treatment (38).

Studies in several jurisdictions have found high levels of unmet need among people with co-occurring disorders (42). A Canadian study found that 51% of individuals with a co-occurring disorder in the community had perceived unmet need for mental health care in the past year, compared with 13% of those with substance use disorder alone and 21% with a mental disorder alone (43). Despite pockets of innovation in services for co-occurring disorders, the steadily increasing incarceration rate among this subgroup is evidence that, overall, people with co-occurring disorders are not receiving appropriate treatment and support in the community.

The 359% increase in methamphetamine use disorder in our sample made methamphetamines the most used drug in 2017 among those with a substance use disorder. This increase is consistent with community studies showing that the availability of and harms associated with methamphetamines have been increasing globally, with the highest prevalence in North America (44–46). The increase in high-risk drug use among this group is particularly concerning in light of the fact that incarceration increases the risk of drug toxicity poisoning after release (47–49).

There may be a relationship between the increase in diagnoses of co-occurring disorders and the changes in drug use patterns, given the strong relationship between co-occurring disorders and methamphetamine use found elsewhere. Studies show that psychiatric symptoms, including hallucinations and paranoid delusions, anxiety, and mood disturbances (50), are common among methamphetamine users and may be related to the effect of methamphetamines on inflammatory pathways in the brain (51). Comorbid psychiatric conditions among people who use methamphetamines are associated with poor treatment outcomes, substance use relapse, and adverse social outcomes, such as unemployment and unstable housing (52, 53). Our study provides robust evidence of increasing co-occurring disorders and high-risk drug use among people who experience incarceration in BC.

To our knowledge, this is the first study globally to examine population-level prevalence trends in the adult prison population using the four mental and substance use disorder classifications. Although the prevalence of substance use disorder among people in prison has been estimated previously, the richness and specificity of our substance use data represent a novel contribution to the literature. Because the JSAT training, policies, and procedures remained consistent throughout the study period, we are confident that our estimates reflect true changes in prevalence over time. Our study used self-report data from a validated, reliable intake screening tool, potentially identifying people who were missed by using other linked data methods. Finally, the data were remarkably complete given the BC provincial mandate to complete the screener for every client.

The primary limitation of our methods was our reliance on an administrative data source that drew upon self-report information and on data that were not collected with the study purpose in mind. Our definition of co-occurring disorder reflected presentations of current substance use disorder and mental health needs at the same time, so our findings may underestimate the prevalence of these disorders. Finally, the JSAT relies primarily on self-reported information, which is known to be subject to bias (e.g., social desirability, recall) (54). However, studies with marginalized populations show that self-report measures are highly reliable and valid, particularly in terms of health care use, drug use, and history of offending (55–58).

Conclusions

Although the presence of mental and substance use disorders in custodial populations presents challenges, prisons provide an opportunity (however regrettable) to identify needs and connect people to treatment in custody or in the community after release. Universal, validated, and detailed screening tools (such as the JSAT) provide a rich source of data that can be used to better understand the population-level health needs of people who go to prison and to strengthen systems-level reform efforts to meet those needs.

The World Health Organization’s Trenčín Statement on Prisons and Mental Health (59) recommended urgent and comprehensive action by public health systems, advocating against the criminalization of people with mental and substance use disorders and acknowledging that prisons are not the appropriate context for the treatment of people with acute or major mental illness. A majority of people admitted to prison have complex, multifaceted health problems that began prior to incarceration (60). Significant challenges exist in achieving rehabilitation because many of these people do not have stable housing, education, and employment. The extent to which poor access to high-quality health care in the community is contributing to the elevated and increasing prevalence of mental and substance use disorders in prisons is unclear. It is important that the health of people in prisons be seen within the broader context of society, including with regard to stigma associated with mental and substance use disorders, the criminalization of poverty, the War on Drugs, systemic and structural racism, and cultural and socioeconomic deprivation. Within this context, the marked increases in the prevalence and complexity of mental health needs among incarcerated people are especially troubling and warrant urgent policy attention.