Abstract

Social science has long acknowledged that juvenile status is a risk factor for falsely confessing,as are coercive strategies utilized in American interrogations. The dangerous interplay between these risk factors is highlighted in the overrepresentation of juveniles among exonerees who were found to have falsely confessed. Courts have determined that age as a risk factor for falsely confessing is within the “common knowledge” of jurors; thus, jurors are expected to accurately weigh whether a confession is false. In this study, participants (n = 131) listened to an audio recording of verified false confession and rated the overall coerciveness of the interrogation and the coerciveness of six different types of interrogation strategies commonly used. Half of the participants were told the suspect was a juvenile (n = 67) while the other half (n = 64) were told the suspect was an adult. Coerciveness ratings of the overall interrogation and five out of the six interrogation strategies did not differ by suspect age. However, participant ratings suggest the overall interrogation was perceived as coercive, as were several interrogation strategies, (e.g.,emotion provocation and confrontation) regardless of suspect age. Coerciveness ratings for the context manipulation strategy (e.g., deliberate alteration of the physical space where the interrogation is being conducted) differed significantly by suspect age. Ratings of false confession likelihood significantly differed by participant ratings of overall interrogation coerciveness, where participants who rated the overall coerciveness of the interrogation to be low perceived the likelihood that the confession was false to be lower than participants who rated the overall coerciveness as high. Furthermore, participants who perceived the confession to be false were more likely to render a verdict of Not Guilty than participants who did not perceive the confession to be false. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Perceptions of Interrogation Tactics in Juvenile False Confessions

Recent years have witnessed a surge in media coverage and documentary productions of criminal cases where there is a focal question of whether a false confession occurred. Series such as Making a Murderer, The Confession Tapes and When They See Us have captivated audiences and brought revitalized awareness to long-standing conclusions of social scientists: juvenile status and interrogation tactics associated with the Reid Technique, the interrogation structure of choice for most law enforcement departments in the United States (Crane et al., 2016; Inbau et al., 2013), are significant risk factors for falsely confessing (American Psychological Association [APA], 2022). The area of false confession, defined as a suspect’s admittance of involvement in a crime along with a detailed account of the crime, which the suspect later retracts and is found to be false (Leo, 2009; The National Registry of Exonerations, n.d.), is a leading contributor of wrongful convictions (Gould & Leo, 2010) and found to be a factor in 12.5% of exoneration cases to date (National Registry of Exonerations, 2024).

Despite ongoing advocacy to adopt less coercive interrogation techniques among American interrogators- a crucial preventative step toward mitigating false confessions- the unfortunate reality that coercive interrogations continue to occur persists. This necessitates a deeper understanding of additional safeguard measures against wrongful convictions. An important safeguard includes the ability of triers of fact (judges and jurors) to be able to identify a false confession, as they hold the responsibility of being the ultimate decider of a suspect’s innocence or guilt. Research on potential jurors is an important avenue of research, as the judicial system posits that certain risk factors (e.g., juvenile status, coercive interrogations) are within the “common knowledge” of jury-eligible citizens, which means expert testimony on known risk factors for false confession is often inadmissible in court because it is seen as unnecessary (Chojnacki et al., 2008). Although at face value it appears intuitive that laypeople would understand the risks both situational and dispositional risk factors pose for falsely confessing, surveys of potential jurors indicate otherwise (Chojnacki et al., 2008; Kaplan et al., 2020; Mindthoff et al., 2018); in fact, the results of these studies suggest participants hold at best naiveté towards the degree of risk age and interrogation tactics pose for falsely confessing, and at worst biased perceptions of these tactics.

To grasp why jurors often downplay the risk of false confessions, one need only consider the profound weight placed on confessions in legal proceedings. Extensive research has shown that regardless of their veracity, confessions are frequently hailed as the most influential piece of evidence in criminal proceedings, even overriding other significant forms of evidence like eyewitness testimony and suspect alibis (Drizin & Leo, 2004; Kassin & Neumann, 1997; Leo & Ofshe, 1998). The compelling force behind confession evidence stems from the paradoxical nature of false confessions, which challenge the commonly held assumption that individuals avoid acting in a way that is detrimental to their self-interest (Kassin, 2008). Experimental studies demonstrate that although individuals will acknowledge false confessions occur (Chojnacki et al., 2008; Henkel et al., 2008), the majority do not believe they themselves would confess to a crime they did not commit (Henkel et al., 2008). Furthermore, mock juror studies suggest laypeople do not discount confession evidence even in scenarios where they believe a confession was coerced, the confession was unsupported, they were informed the confession was declared inadmissible, or when told DNA evidence later excluded the suspect (Appleby & Kassin, 2016; Conti, 1999; Kassin & Sukel, 1997; Lassiter & Geers, 2004). These results underscore the overwhelmingly powerful bias individuals harbor regarding confession evidence.

Compounding the bias laypeople have toward confession evidence is research indicating that a majority of individuals are unaware of factors that heighten a suspect’s vulnerability to falsely confess (Chojnacki et al., 2008; Leo & Liu, 2009). Risk factors are typically classified by social scientists into two main groups: situational or dispositional risk factors (Perillo & Kassin, 2011). Situational factors encompass external influences that increase a suspect’s susceptibility. Within the false confession literature, situational factors predominantly arise from aspects of police interrogation strategies (Kassin, 2017). Police interrogations are often categorized into one of two approaches: the information-gathering approach or the accusatorial approach (Bartol & Bartol, 2019). In the U.S., law enforcement officials have widely adopted the “Reid Technique” for suspect interrogation, which is a highly accusatorial approach to interactions with suspects. This method aims to extract a confession or incriminating information likely to lead to the suspect’s conviction (Bartol & Bartol, 2019). Developed in 1942 by Fred Inbau and John Reid, the Reid Technique for interrogation focuses on presuming guilt and obtaining a confession (Kozinski, 2018).

Broadly, accusatorial approaches to interrogation, like the Reid Technique, are widely criticized, and the Technique’s ability to accurately obtain true confessions as opposed to false confessions has been questioned (Meissner et al., 2014). A 2014 meta-analytic review by Meissner and colleagues compared accusatorial interrogations to information-gathering interrogation methods and the influence each exhibits in eliciting confessions. Based on 17 studies (five field studies and 12 experimental studies), the results demonstrated that accusatorial interrogation methods significantly increased the likelihood of both true and false confessions. In contrast, information-gathering interrogation methods significantly increased the likelihood of eliciting a true confession and decreased the rate of false confessions when directly compared to accusatorial methods. In an effort to obtain better awareness of problematic interrogation strategies, researchers have attempted to identify specific strategies that are the most problematic (Kelly et al., 2013; Leo, 2020); however, the majority of previous research has focused on broadlevel categories of interrogation strategies. The issue with the broad-level scope is that it lacks the ability to capture nuances within the interrogation that might be problematic (e.g., the process of the interrogation and dynamic between interrogator and suspect) (Kelly et al., 2013). To address this gap, Kelly and colleagues (2013) reviewed the existing interrogation literature to identify 71 unique strategies utilized by law enforcement that fall within six broad categories, including rapport and relationship building, context manipulation, emotion provocation, confrontation and competition, collaboration and presentation of evidence. Across all categories, the strategies are designed to utilize deception (David et al., 2017), maximize suspect distress (Inbau et al., 2013), and elicit feelings of despair and hopelessness (Gudjonsson, 2003; Odagiu & Lungu, 2021) to obtain a confession.

Although these interrogation strategies are problematic for suspects for all ages, juveniles are at particular risk to respond to these psychologically manipulative strategies due to their developmental immaturity, some of which can be linked to their brain development (Steinberg et al., 2013). For example, research indicates that the subcortical areas of the brain responsible for emotion and reward-processing experiences a rapid rate of dopaminergic activity during adolescence (Smith et al., 2013; Steinberg, 1010), while the prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and self-regulation, develops much slower (Arain et al., 2013; Casey et al., 2008; Steinberg, 2010). The consequences that emerge for adolescents from the imbalance between systems include being less likely to adaptively manage stress in high-arousal situations (Casey & Caudle, 2013; Cohen et al., 2016), being more likely to prioritize short-term benefits over long-term self-interests (Davis & Leo, 2012), and having a limited ability to make connections between current behavior and potential future consequences (Steinberg et al., 2009). Applying these general orientations to situations in which a juvenile is interacting with the criminal justice system, studies have demonstrated juveniles’ preference for engaging in behaviors that will speed up the interrogation process, even to their own detriment. For example, several studies have found adolescents’ desire to go home and/or get the interrogation over with as leading motivations for confessing, in both true (Malloy et al., 2014) and false confession cases (Drizin & Colgan, 2004).

The neurological immaturity of young people has been well established, but socialization of youth also increases their vulnerability for false confession. Generally, youth are regarded as subordinate to adults and therefore are expected to respect and obey adults and other authority figures (Cleary, 2017; Koocher, 1991). Interrogations create a unique authoritative imbalance for adolescents, as interrogators not only possess natural authority as an adult but also via the powerful societal status law enforcement holds. In a study examining youth legal decisionmaking, Grisso and colleagues (2003) found that, when presented with a vignette situation, participants aged 15-years- old and younger were significantly more likely to confess to law enforcement and/or accept a prosecutor’s plea deal than young adults (ages 16-24-years-old). The vulnerabilities created by the neurological and social influences of adolescence become strikingly apparent in cases of false confession. In general, juveniles are overrepresented in known false confession cases, making up a disproportional 33% to 38% of total wrongful convictions (Drizin & Leo, 2004; Garrett, 2015). Support for the notion that developmental limitations account for the decision-making and judgement of adolescents are particularly observable when comparing the proportion of known juvenile false confessions to the proportion of known adult false confessions. For example, Gross et al. (2004) examined exoneration data from 1989 through 2003 and discovered that 42% of the juvenile exonerees had falsely confessed, in comparison to just 13% of the adult exonerees. The study further clarified that out of the 33 total juvenile exonerees who admitted to falsely confessing, 69% of those were of the youngest age group, aged 12 to 15-years-old, whereas 25% of the juveniles who falsely confessed were aged 16 to 17-years-old. Another study by Gudjonsson et al. (2016) further underscores the incremental risk for false confession as a function of younger age, as youth aged 14 to 16-years-old were twice as likely as youth aged 17 to 24-years-old to falsely confess during an interrogation.

Currently, there is limited research regarding potential juror perceptions of juvenile false confession, with the current research in this area providing mixed results. Given juveniles are known to be at risk for falsely confessing and Courts operate under the ruling that juries possess the knowledge of this risk factor and are able to make determinations about when a coercive interrogation that might have induced a false confession has occurred, we aimed to examine the perceptions of the coerciveness of a known false confession by asking participants to make both a broad judgement about the coerciveness of the interrogation and to identify and judge the coerciveness of specific aspects of the interrogation using the categories identified by Kelly and colleagues (2013). To this writer’s knowledge, there are no studies to date examining juroreligible participants’ ability to recognize the coerciveness of commonly used interrogation tactics with juvenile suspects. To bridge this gap, we compared participants’ judgments of an interrogation that they were told was a juvenile suspect versus an interrogation of an adult suspect. We also compared participants’ ratings of the likelihood the confession was false by degree of interrogation coerciveness identified, as well as how participants’ perception of the veracity of the confession influenced their verdict judgement.

Method

Participants

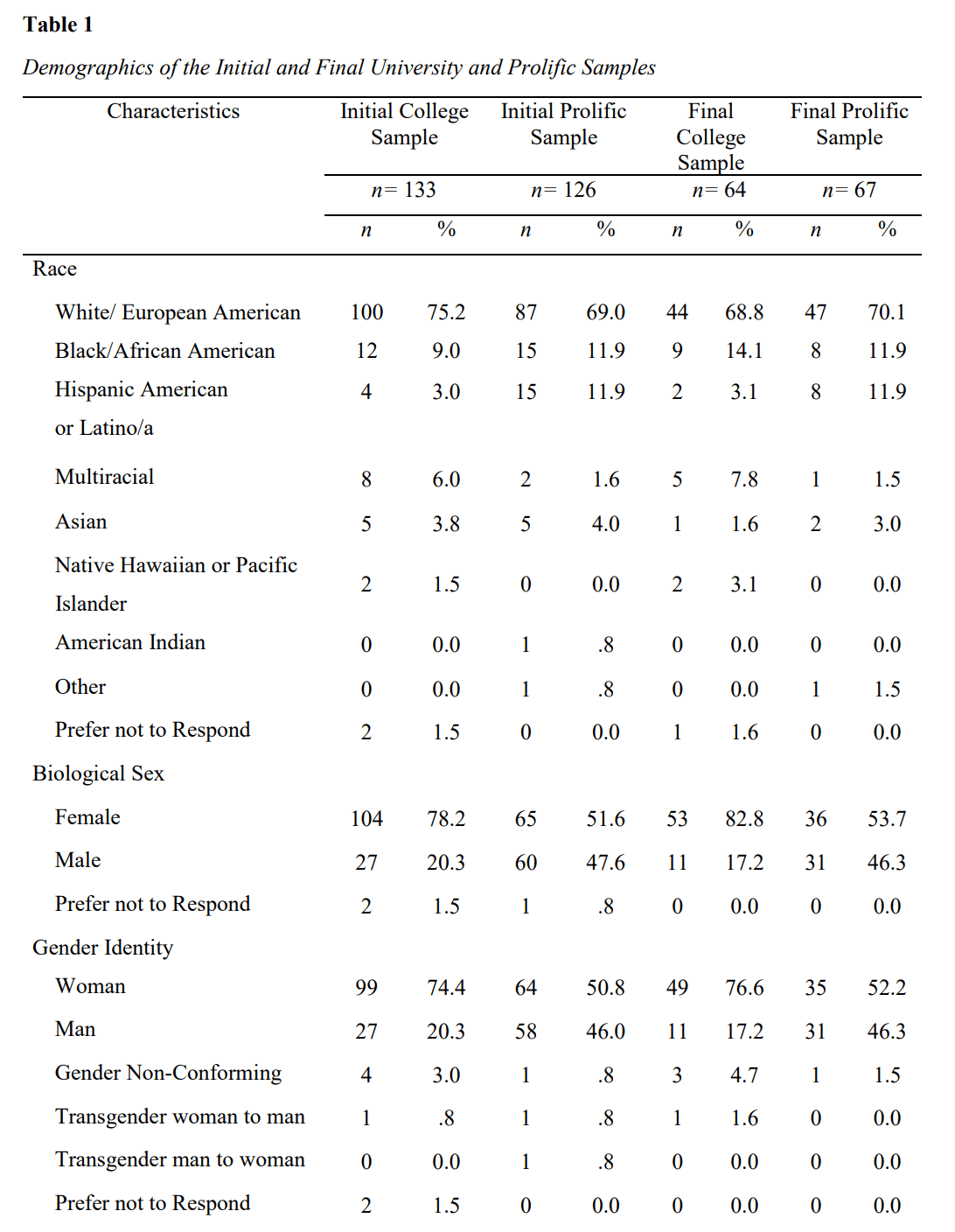

A total of 259 participants completed the study. The demographic characteristics of the total sample are in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 30.12 years old; the majority identified as a Woman (n = 85, 64.9%) and as White/European American (n = 91, 69.5%). Participants were recruited using two different strategies; approximately half (n = 64) were recruited through a university participant pool and the remaining (n = 67) were recruited through Prolific, a crowdsourcing platform that provided access to older and more demographically diverse participants.

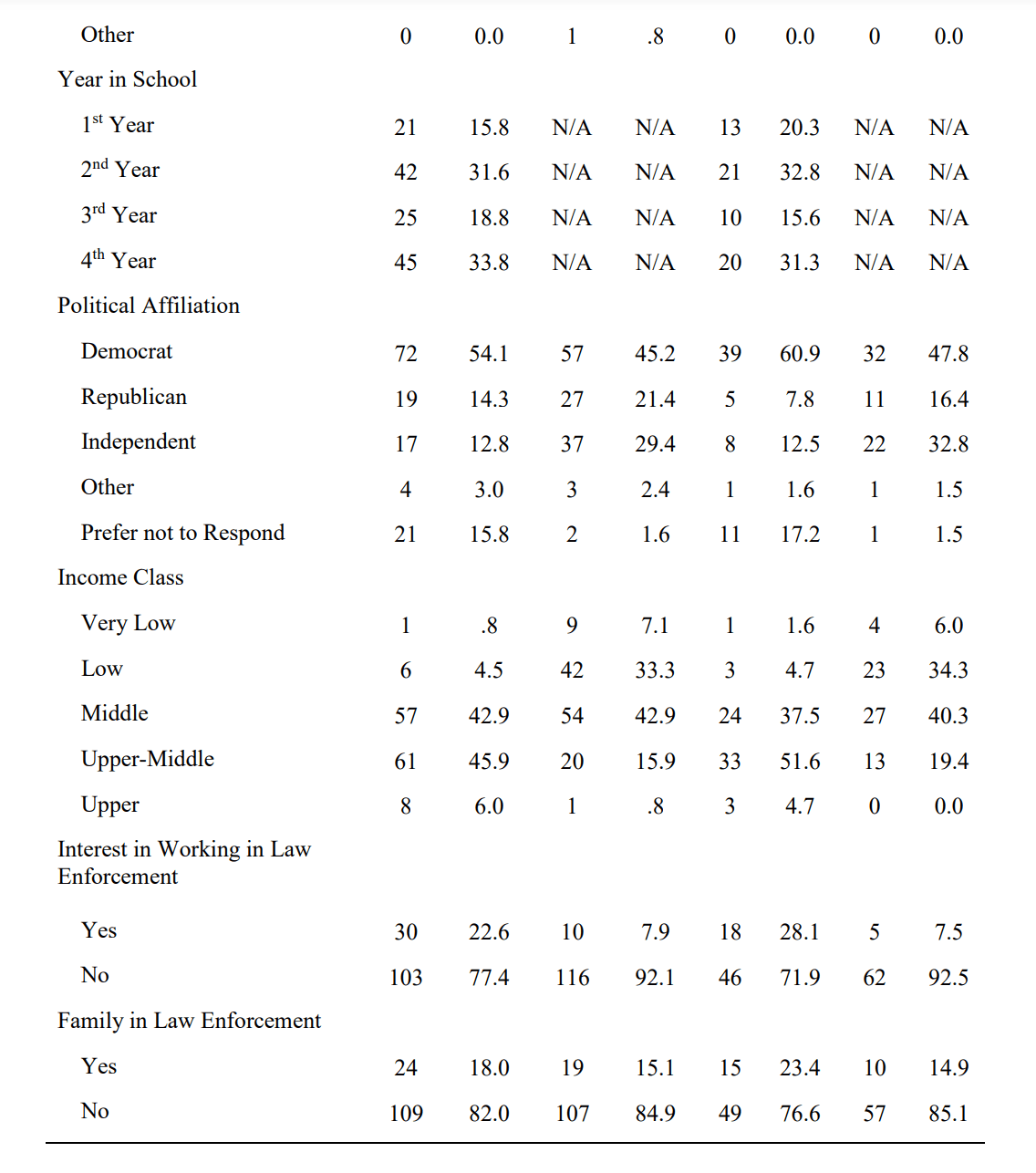

The independent variable of the study was the age of the suspect presented in the study materials. A manipulation check was utilized to assure that participants correctly identified the age of the suspect. As data collection progressed, it became apparent that participants who were informed they had heard the interrogation of a 25-year-old suspect were not accurately identifying the exact age of the suspect, resulting in a large number of excluded participants. Table 2 displays the correct suspect age identification rates for the initial college and Prolific samples. Given the level of inaccuracy, we decided to consider a range of ages (21 to 30 years) as acceptable to pass the manipulation check. The age range of 21 to 30 years old was chosen as it captured the majority of responses and clearly indicated the suspect was perceived as an adult. This resulted in a final sample of 131 participants. The demographic characteristics of the final sample are also presented in Table 1; the initial sample and the final sample did not differ significantly in any of the demographic characteristics.

Stimuli

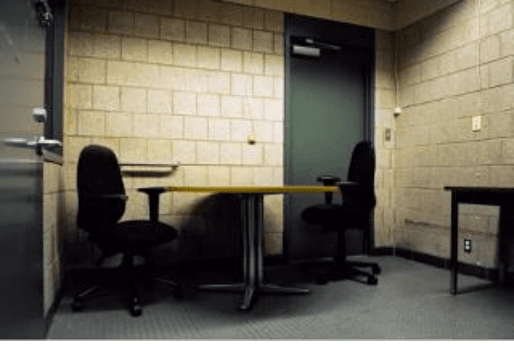

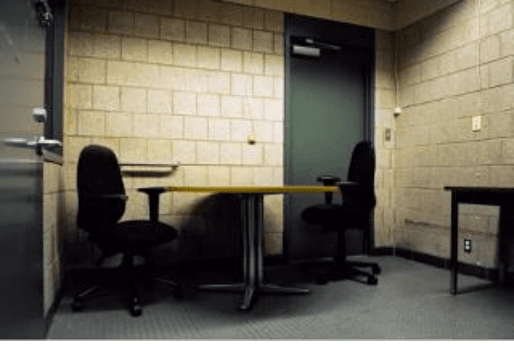

Participants listened to an actual interrogation obtained from a publicly broadcasted show. The full interrogation lasted over 7-hours, but the audio condensed the interrogation to 4- minutes and 2-seconds in length (see Appendix A for transcript). The audio involves two detectives questioning a suspect about the murder of the suspect’s aunt and uncle. The listener heard the detectives harshly questioning and accusing the suspect of murdering his aunt and uncle. The recording includes with end of the interrogation at which point the suspect confessed to the crime. Prior to hearing the audio recording, participants read a description (see Appendix B) of the circumstances surrounding the questioning, including the nature of the accusation and basic information about the suspect. A picture of a typical interrogation room was also included in the description of the interrogation to address the context manipulation tactic category. The description varied by the age of the suspect; half of the participants read a description in which the suspect was identified as a 25-year-old (Appendix B, Description 1) and half read a description in which the suspect was identified as a 14-year-old (Appendix B, Description 2). In the 14-year-old description, an additional statement was added to the end of the description stating that although the interrogation was real, because the suspect was a juvenile, the audio had been muffled and distorted in various ways. This was done in an effort to encourage participants to believe the suspect was a juvenile, despite the voice resembling that of an adult. While the audio played aloud, a transcription of the interrogation was shown on the screen, to ensure that the participant was able to understand what was being said (Appendix C).

Measures

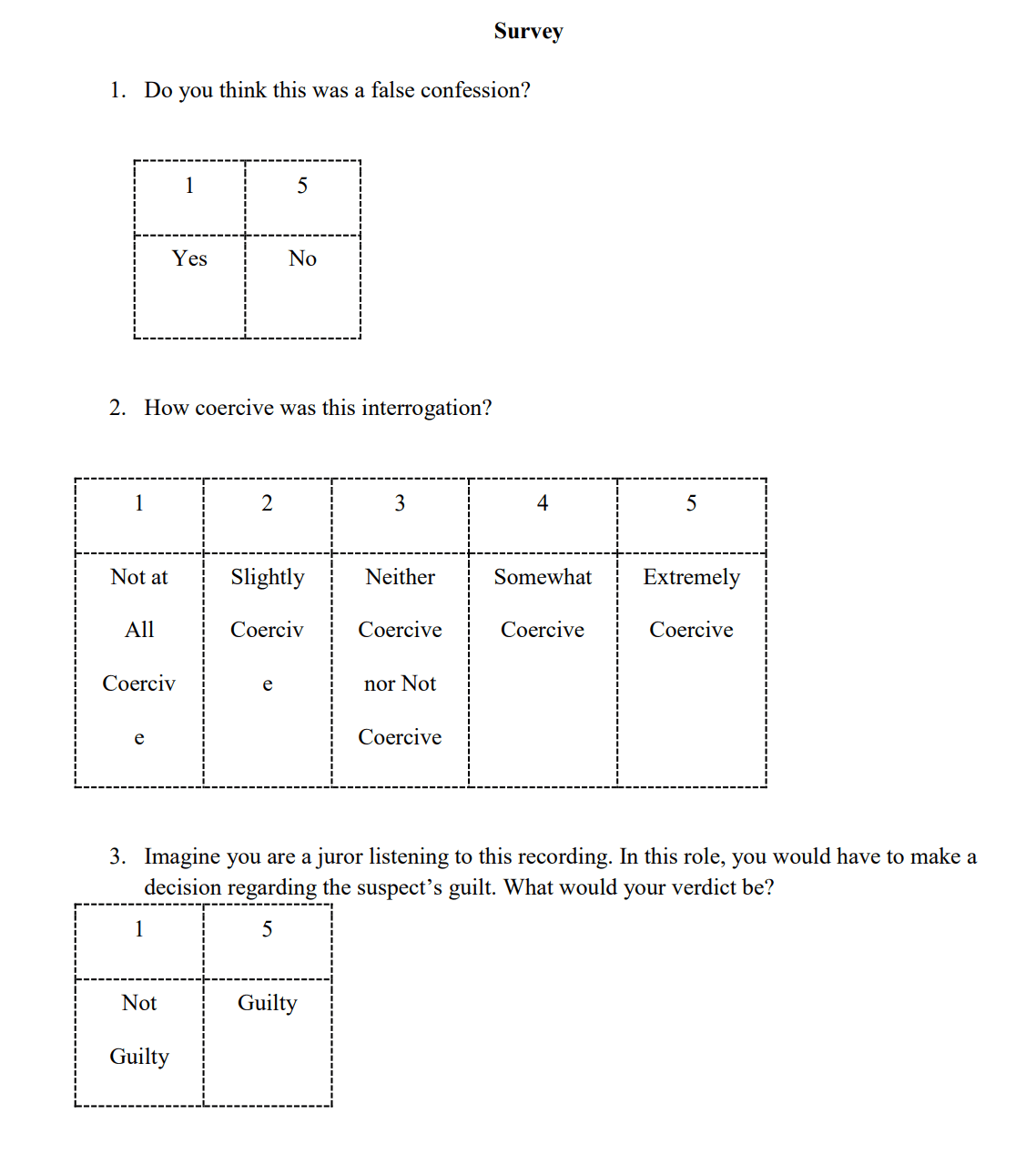

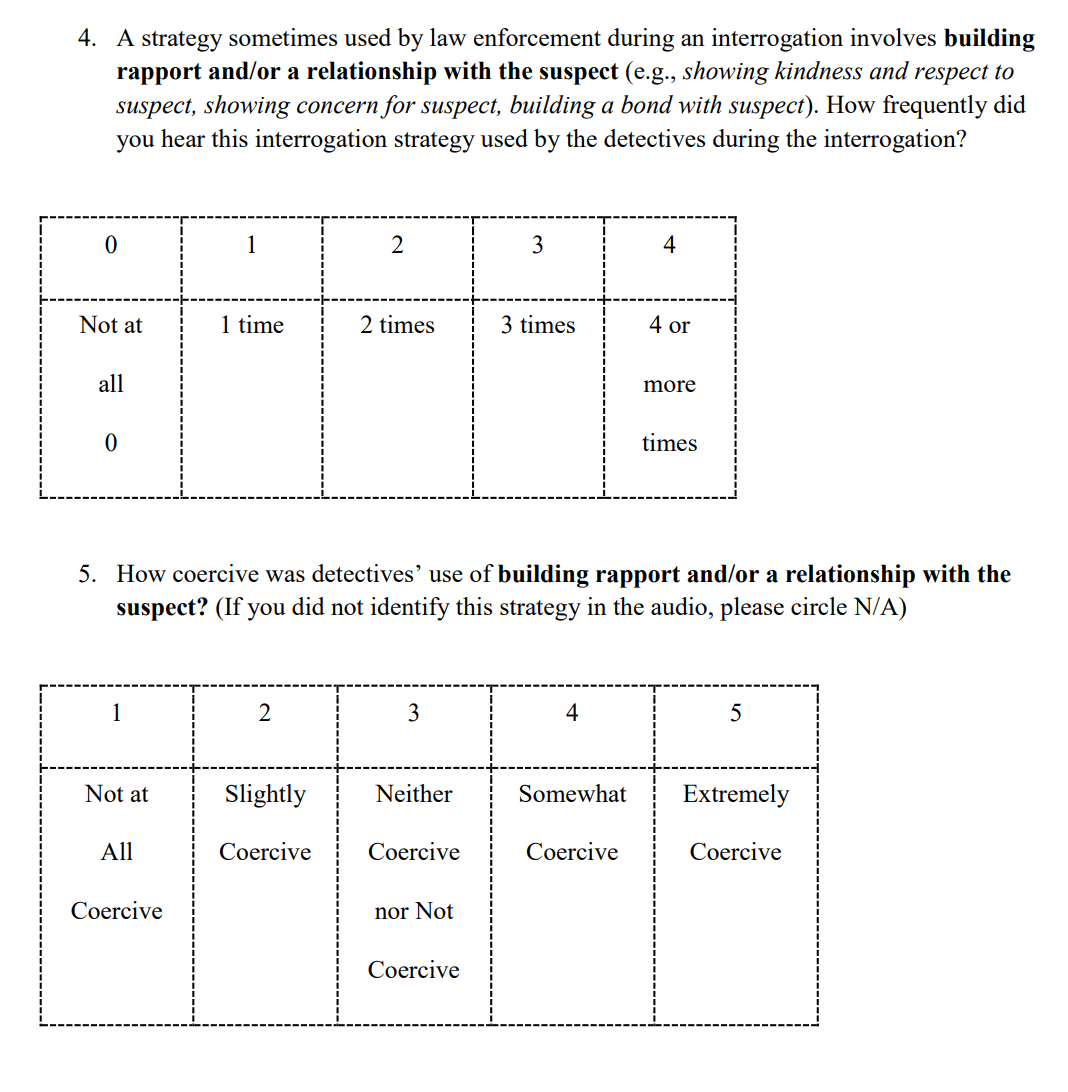

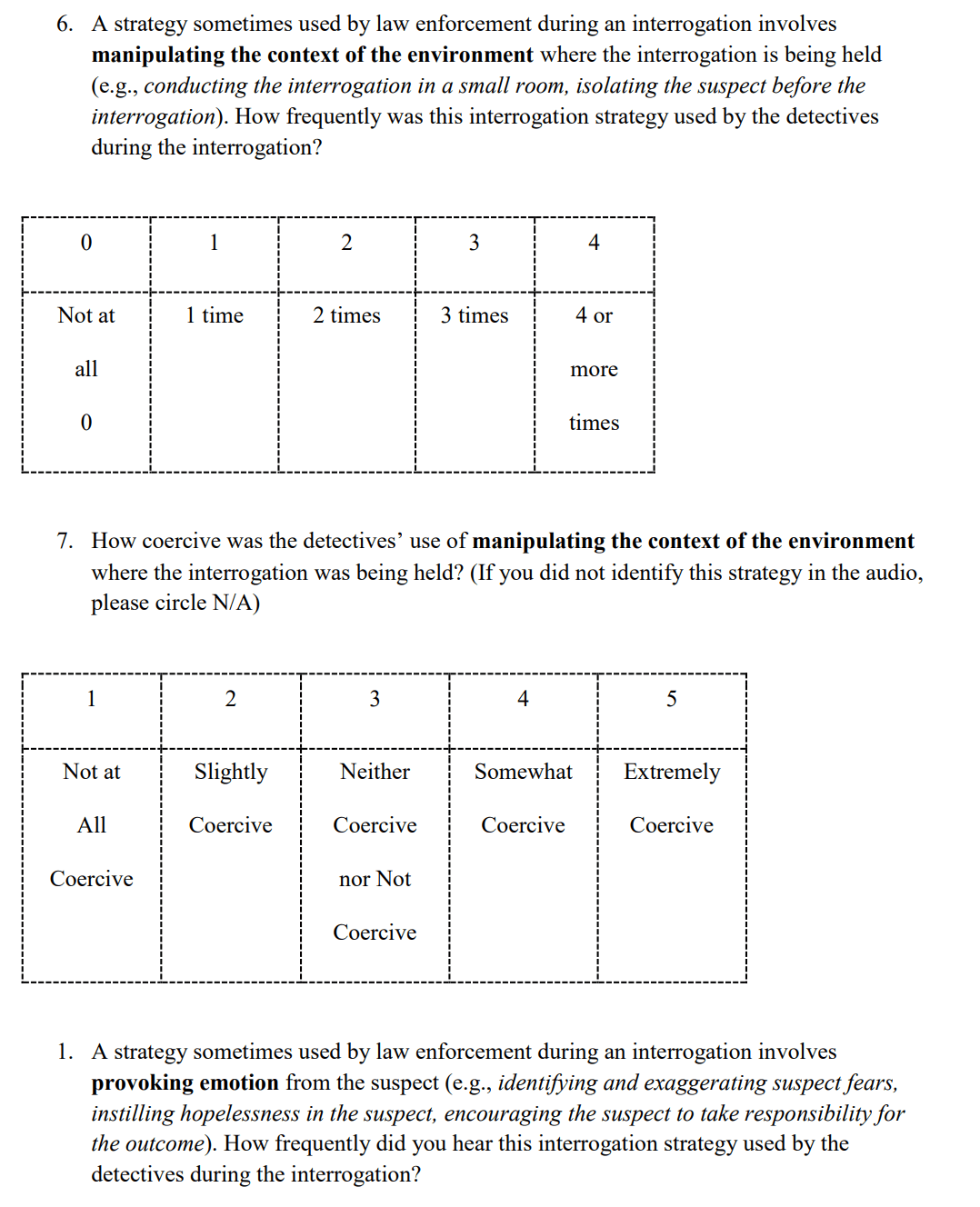

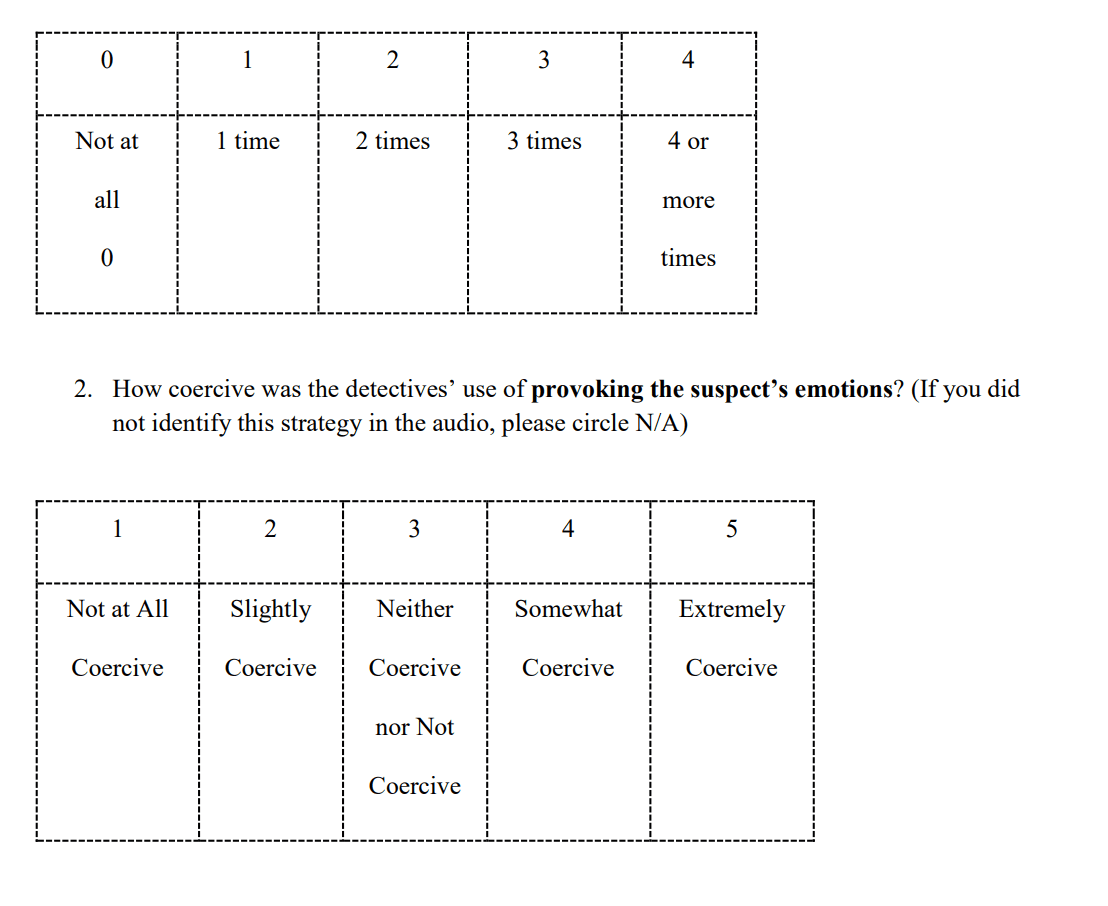

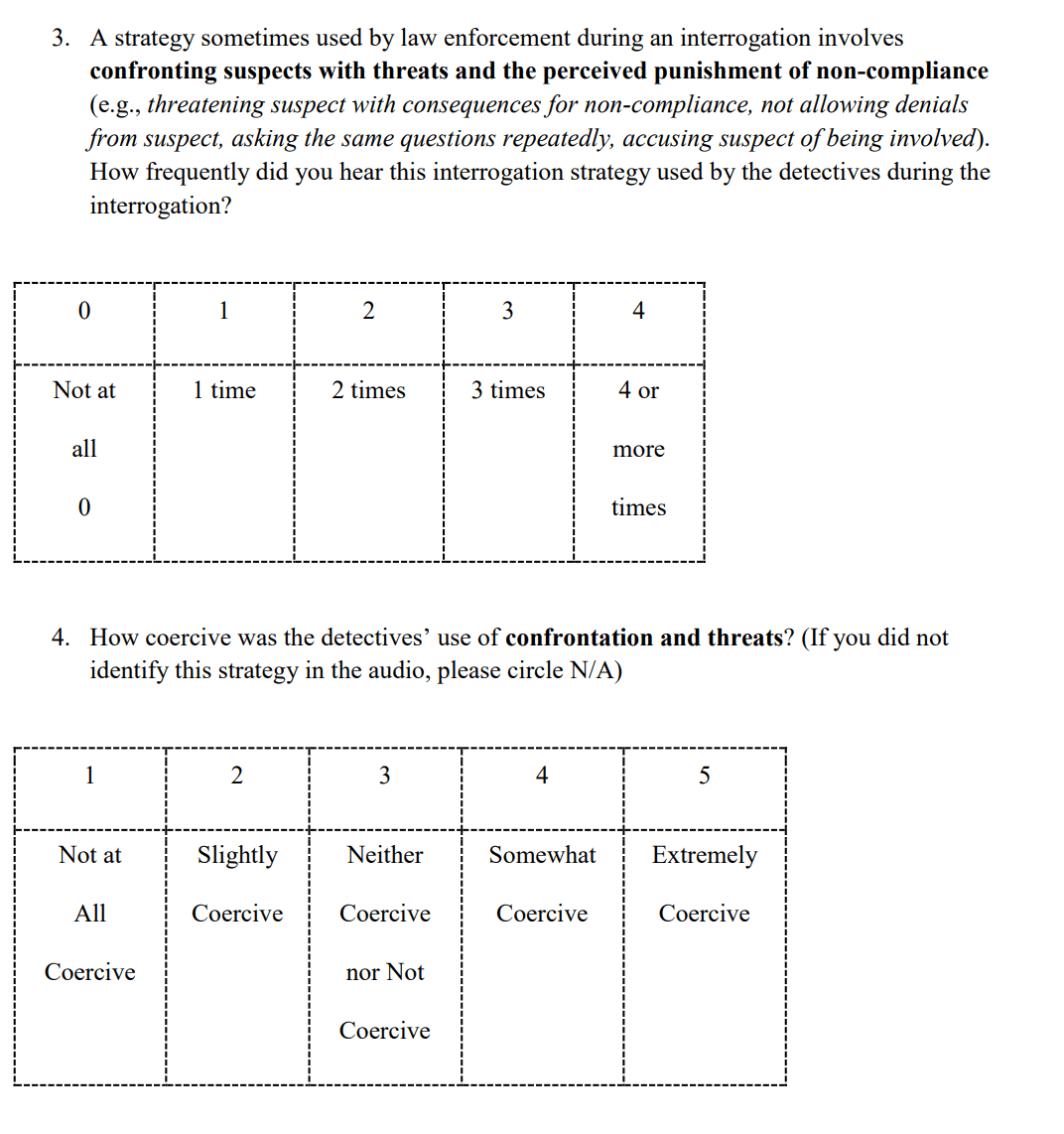

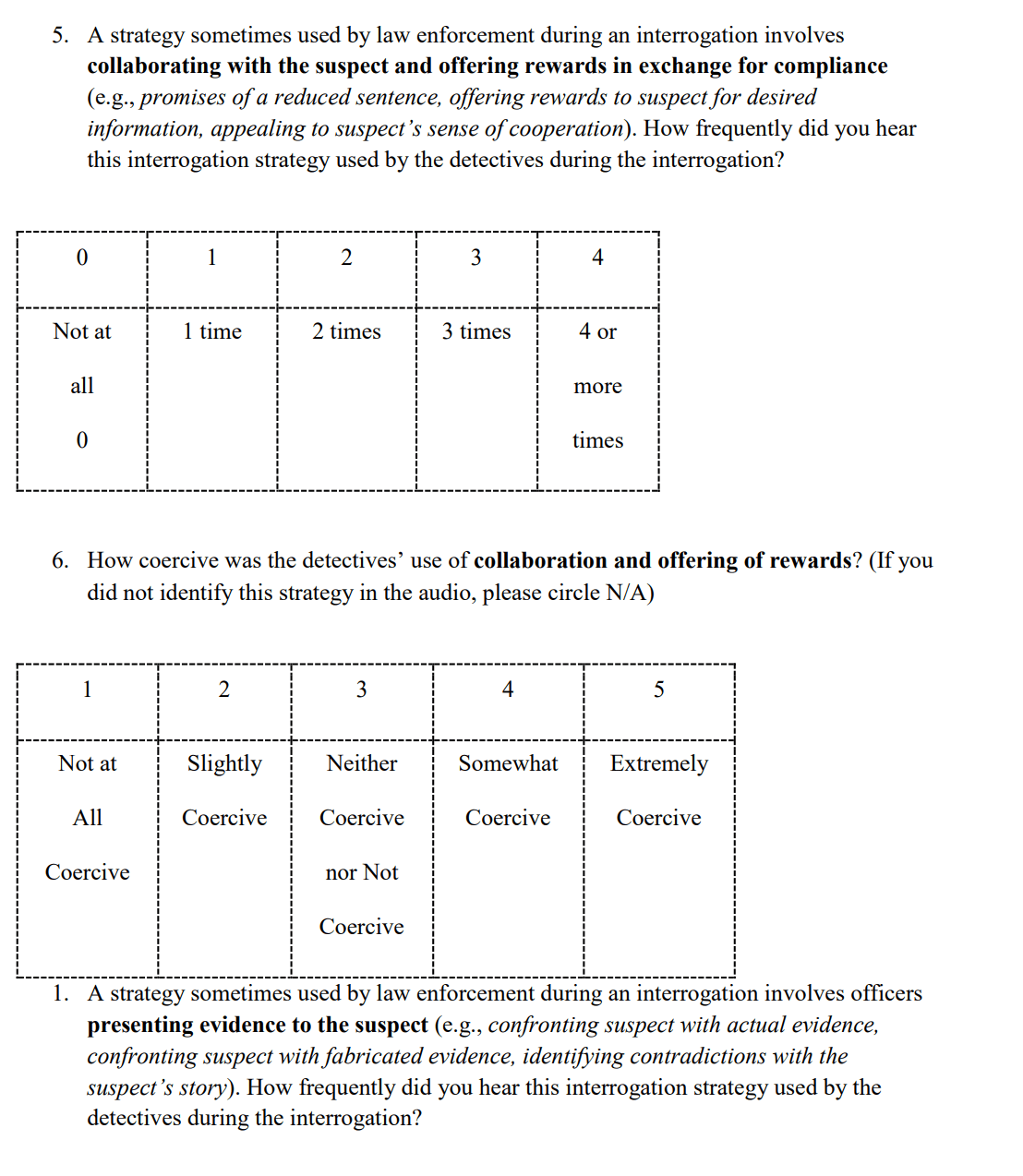

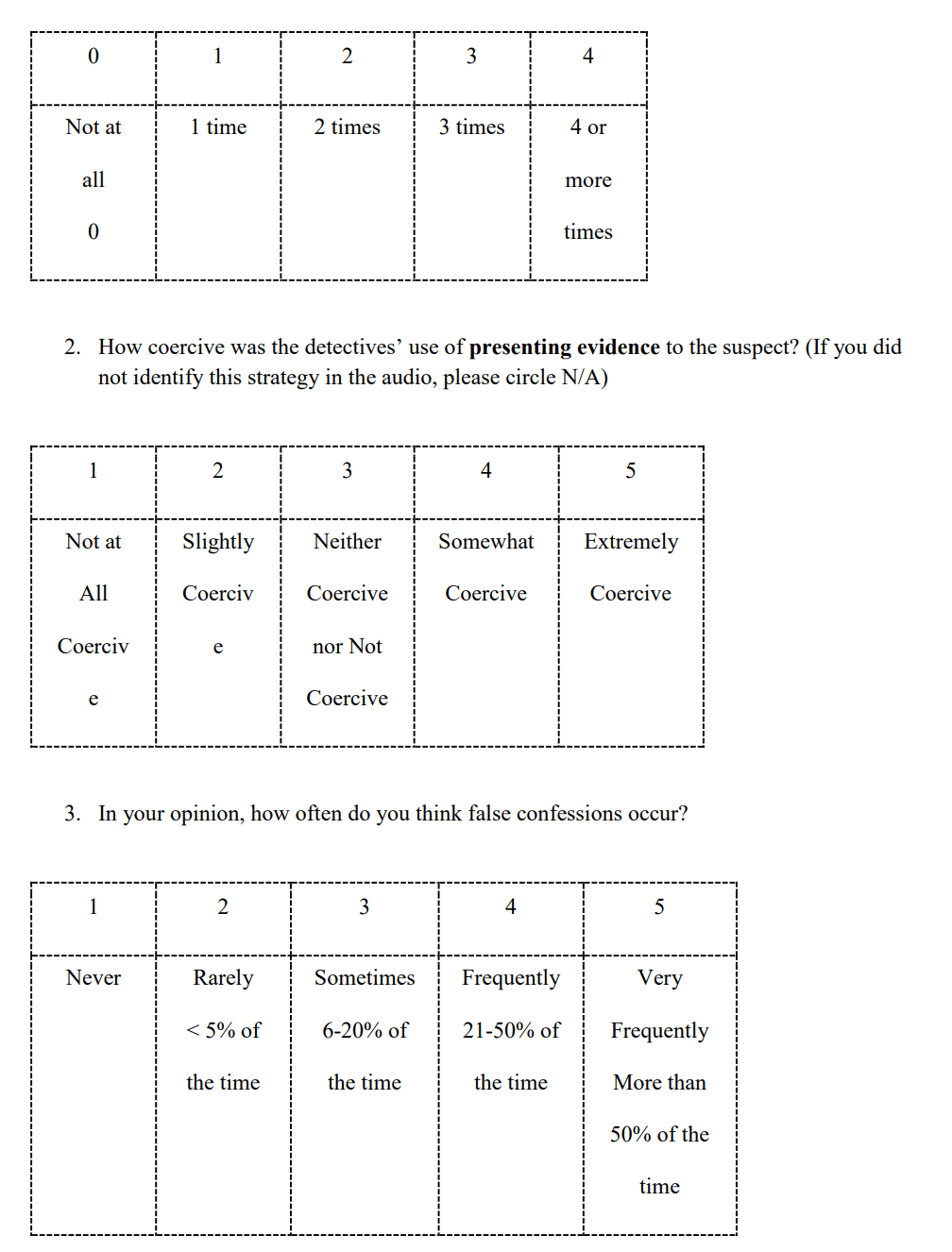

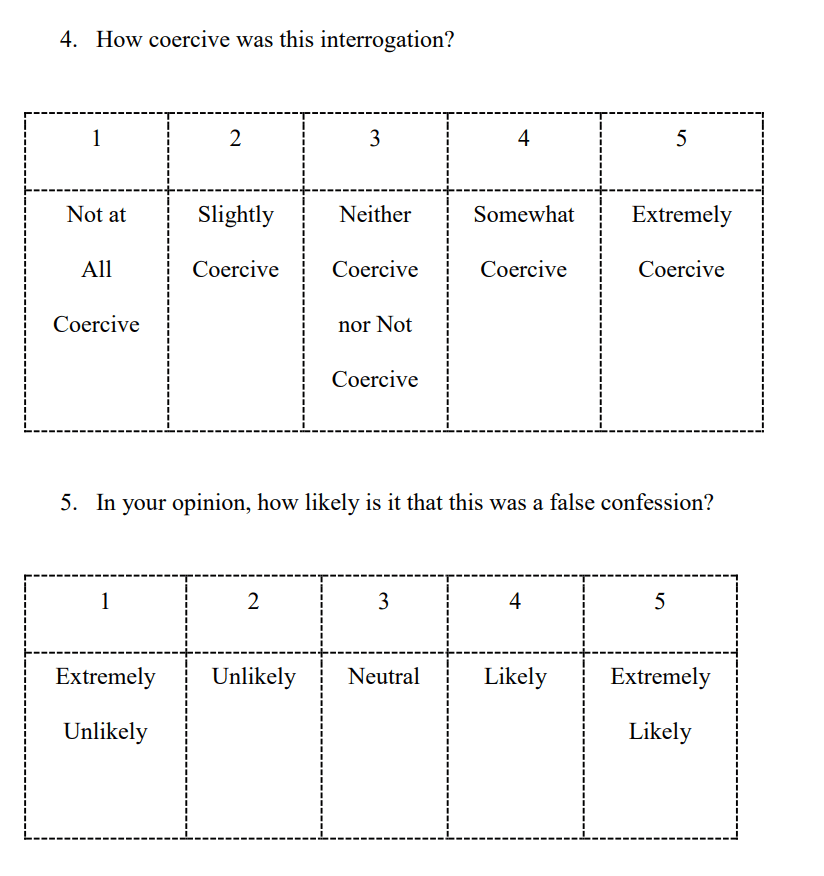

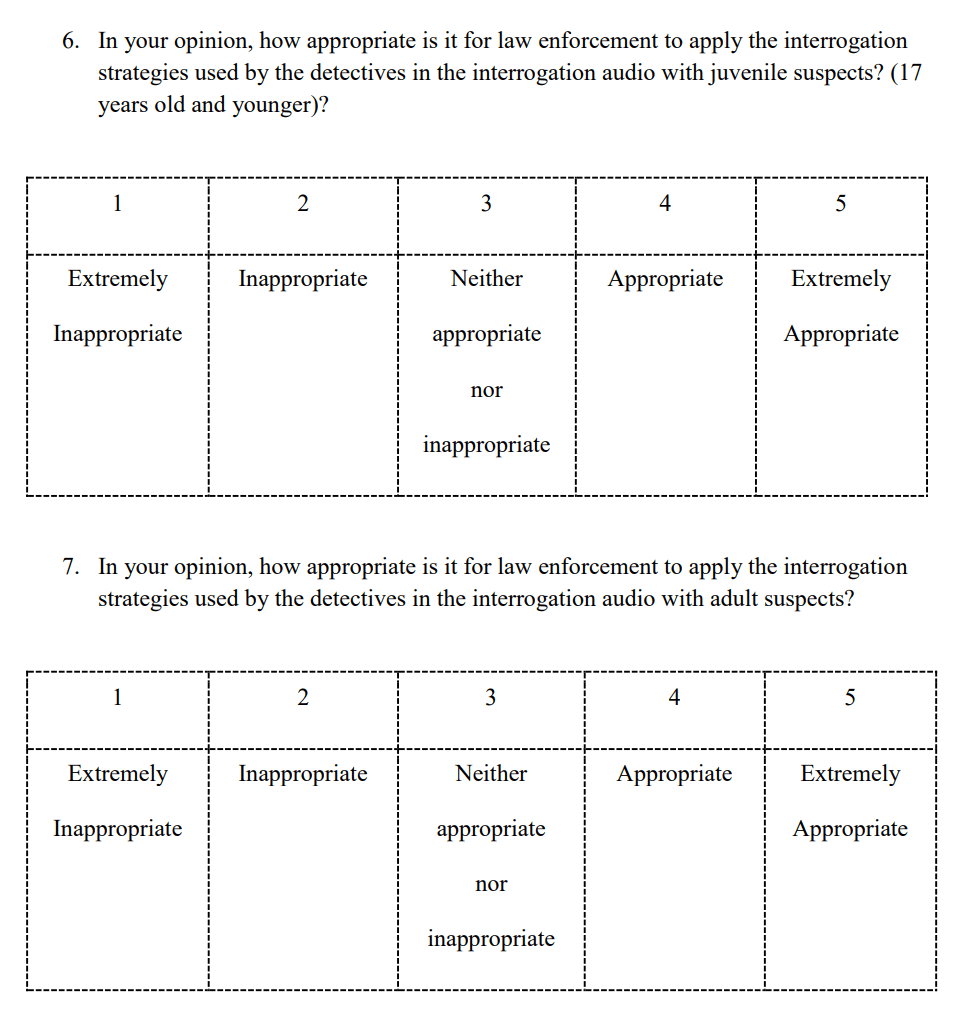

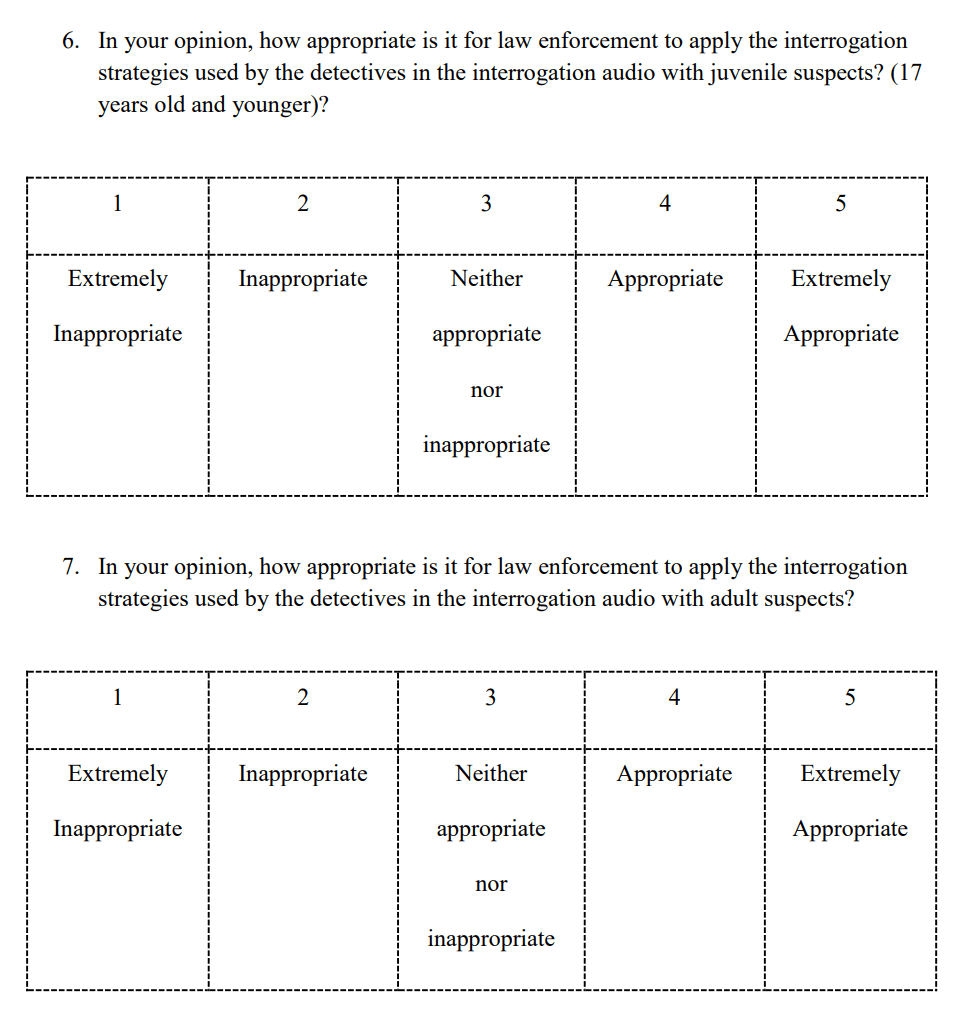

Survey. Participants completed an online survey via Qualtrics (see Appendix D). Participants answered questions regarding the presence of interrogation strategies used by police during the interrogation and, when they indicated that the strategy was present in the interrogation, they rated their perceptions of the coerciveness of that interrogation strategy. Survey questions regarding police interrogation strategies were designed by the author of this dissertation, based on Kelly and colleagues (2013) taxonomy of law enforcement interrogation methods which include rapport and relationship building, context manipulation, emotion provocation, confrontation and competition, collaboration and presentation of evidence. Kelly et al. (2013) described rapport and relationship building strategy to consist of behaviors that aid in developing a relationship with the suspect. Context manipulation involves deliberately altering the physical space where the interrogation is being conducted to increase the likelihood that a confession is obtained. The third category, emotion provocation, is defined as an interrogator’s ability to evoke an emotional state in the suspect that increases the chance of confession. Confrontation and competition are defined as using threats and descriptions of potential punishment the suspect may face if convicted. In contrast, the collaboration taxonomy focuses on rewards the suspect can gain if they cooperate with the interrogators. The sixth and final category of presentation of evidence involves tactics that convey to the suspect information already known about a crime in an effort to obtain additional information from the suspect. In addition, participants answered questions regarding perceptions of the confession (i.e., false confession vs. not), suspect’s guilt (guilty vs. not guilty) and general questions.

Specific questions about the audio recording served as the dependent variables in this study. These included a rating of the overall coerciveness of the interrogation (Q2) and identification of the specific interrogation strategies displayed in the audio (Q4, Q6, Q8, Q10, Q12, Q14). It is important to note that for each of the six interrogation strategies, participants were first asked whether they perceived the interrogation strategy to be present in the interrogation. If they did not perceive the strategy to be present, they did not rate the coerciveness of that strategy. As a result, widely different numbers of participants rated each of the strategies.

Participants were also asked questions regarding the coerciveness of the specific interrogation strategies used by detectives during the interrogation (Q5, Q7, Q9, Q11, Q13, Q15); guilt of the suspect (Q3); and likelihood the confession was false (Q18). For Hypothesis 8, we investigated the influence overall interrogation coerciveness had on participants’ ratings of the likelihood that the confession was false. This resulted in the creation of two groups of participants (High Coerciveness vs. Low Coerciveness), with participants who provided a rating of 1 or 2 (reflecting ‘Not at All Coercive’ or ‘Slightly Coercive’ ratings) being assigned to the Low Coerciveness group and participants who provided a rating of 3 or 4 (reflecting ‘Somewhat Coercive’ or ‘Extremely Coercive) being assigned to the High Coerciveness group. The three participants who provided a rating of 3 (reflecting a ‘Neither Coercive nor Not Coercive’ rating) were excluded from this analysis.

Additional questions regarding exposure to true crime media involving confessions (Qs 21-23) and the appropriateness of using interrogation strategies identified in the audio with juveniles and adults (Qs19-20) were also included for potential exploratory analyses.

Manipulation check. Participants were asked four questions (items 24-27) at the end of the survey about features of the interrogation and to identify the age of the suspect to ensure that participants had correctly identified the independent variable of age of the suspect (see Appendix E). It also included other questions, such as the suspect’s name, how many detectives were involved in the interrogation and the interrogation length, although these questions were not used to exclude participants’ data from the analyses.

Demographic Information. For all participants recruited through both the university and Prolific, demographic information was obtained after participation in the study using the demographic form (see Appendix F). The demographic information included the participant’s current age, sex, gender identity, race, ethnicity, year in school, major area of study, political affiliation, income and if any immediate or extended family members are employed in law enforcement. It should be noted that unlike the University participants, Prolific participants did not complete the year in school or major area of study questions.

Procedure

The home university’s Institutional Review Board reviewed all study procedures prior to the study being administered via Qualtrics (IRB Protocol #23-078). Once approved by the IRB, participants were recruited through the university’s participant pool using the established procedures. Participants from Prolific were offered the opportunity to participate through an ad on the online crowdsourcing platform, and a link to the study was made available to them. Both recruitment and the study were administered online for all participants. Upon accessing the study link, participants were provided with the informed consent after which they read a description explaining the steps involved in completing the study, which included listening to an audio recording and completing a survey. In the description, participants read about the nature of the audio recording and that they would simultaneously see a transcript of the recording on the screen to make it easier to follow. They then read a brief description regarding the content of the survey. Following this description, there was a listener discretion warning that the audio contained explicit language and details about a crime that some individuals may find disturbing. Participants who chose to proceed with the study clicked on a link and listened to the 4-minute, 28-second audio while they read along with the transcript. Participants then completed a 27- question survey that involved questions pertaining to the audio, as well as general questions regarding participant perceptions. The last four questions of the survey served as manipulation checks to verify participants correctly attended to the age of the suspect. After completing the survey, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Participants were then debriefed with a form disclosing that the audio recording was a real interrogation, which involved a known false confession. Furthermore, the debriefing form also informed participants that the purpose of the study was to investigate perceptions of interrogation tactics and false confessions and whether perceptions and judgments differed by the suspect’s age. Lastly, college student participants who completed the survey were awarded research credits, while Prolific participants who completed the survey and the attention checks were paid $2.14 for their time, which is an amount in keeping with Prolific requirements.

Results

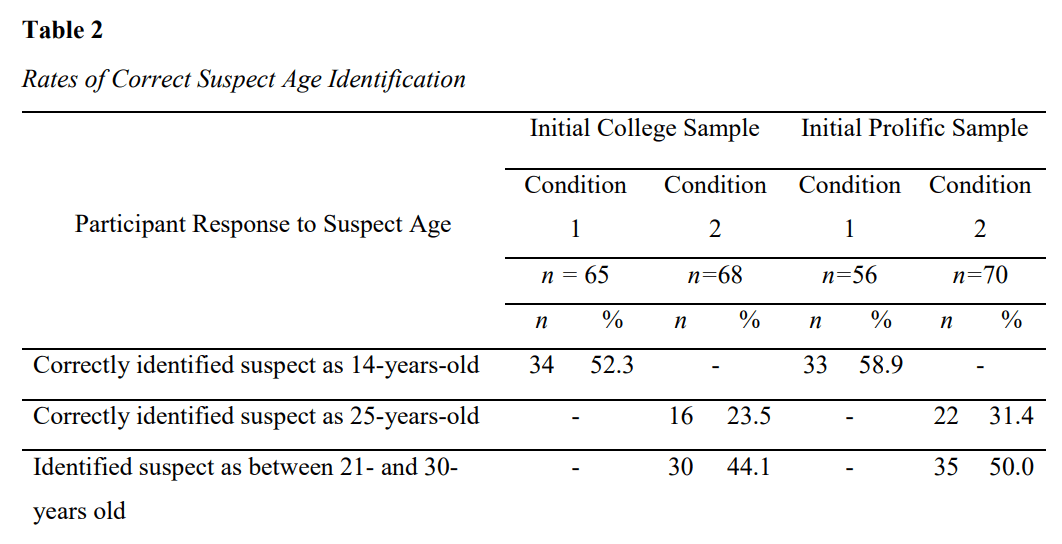

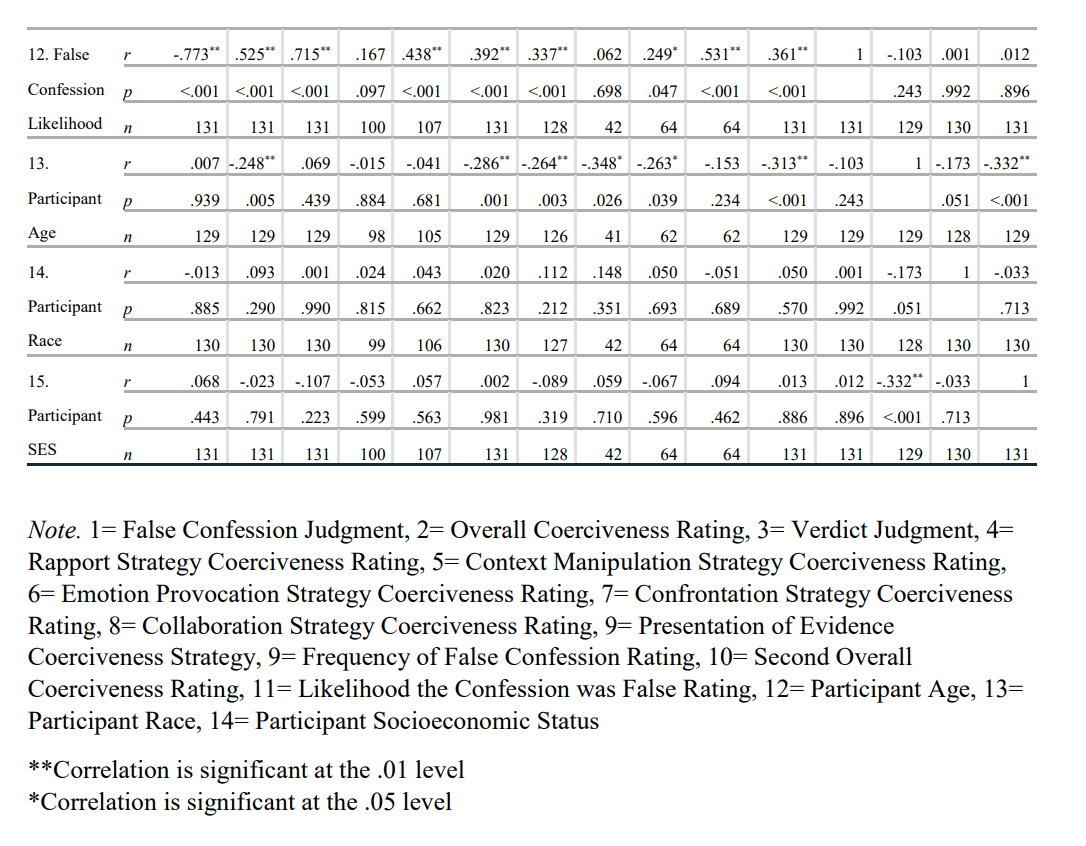

Before running any of the primary analyses, we conducted Pearson’s correlations on all study variables to determine the degree to which these ratings overlapped. These correlations are in Table 3. Several significant correlations between overall coerciveness of the interrogation and the coerciveness of specific interrogation strategies emerged. Of the six types of interrogation strategies, four were significantly correlated with overall interrogation coerciveness and/or participant age. Specifically, rapport and relationship building was not significantly correlated with overall coerciveness or participant age, whereas context manipulation (r =.36) and presentation of evidence interrogation strategies (r = .35) were significantly correlated with overall coerciveness and emotion provocation (r =.52; participant age r = -.29) and confrontation (r = .62; participant age r = -.26) were significantly correlated with both overall coerciveness and participant age. Therefore, for these variables, we used ANCOVA with covariates for overall coerciveness and age, as described above.

As previously noted, participants were first asked to indicate whether they perceived the interrogation strategy of interest to be present and if so, the frequency with which the strategy was utilized during the interrogation. For participants who did indicate the presence of the strategy they then proceeded to the next question, which asked them to rate how coercive they perceived the interrogation to be. In contrast, participants who did not indicate the presence of an interrogation strategy were not asked to provide a coerciveness rating for that interrogation strategy and skipped to the next question in the survey. This resulted in wide variability in the numbers of participants who rated each of the strategies.

The overarching aim of this study is to investigate participants’ ability to recognize the presence of specific interrogation strategies in an audio interrogation and to examine their perceptions of the coerciveness of those strategies when they are used in an interrogation of a juvenile versus an adult. In these ratings we compared the coerciveness perceptions of participants in the juvenile condition versus the adult condition and evaluated how participants’ interrogation coerciveness ratings impacted their perception of the confession being false and whether participants who perceived the confession to be false would be more likely to render a verdict of Not Guilty than participants who did not perceive the confession to be false.

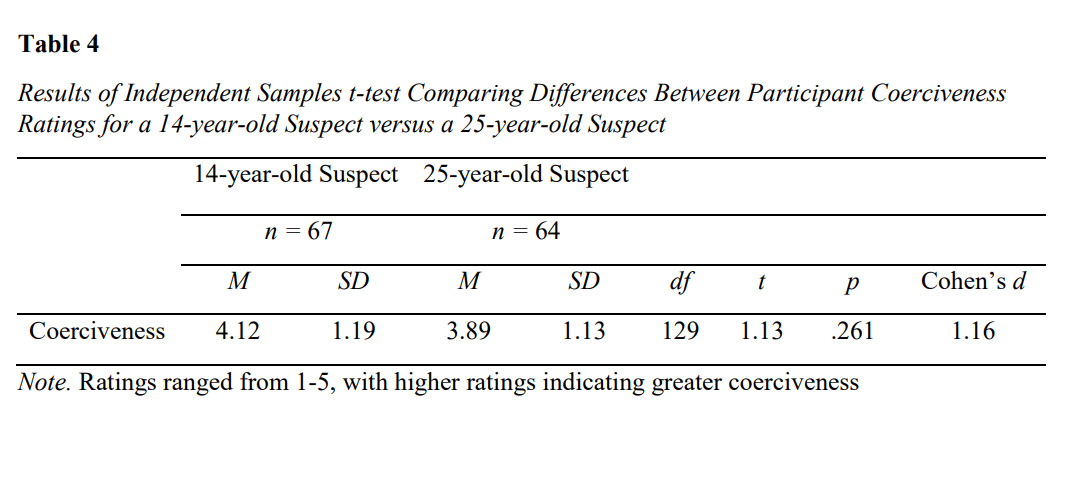

Overall Interrogation Coerciveness. We used an independent samples t-test to examine participants’ ratings of the overall coerciveness of the confession by suspect age (14-years vs. 25-years). Specifically, participants rated, “How coercive was this interrogation?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and independent samples t-test results are presented in Table 4. The ratings of interrogation coercion did not differ by suspect age, t(129) = 1.13, p = .261.

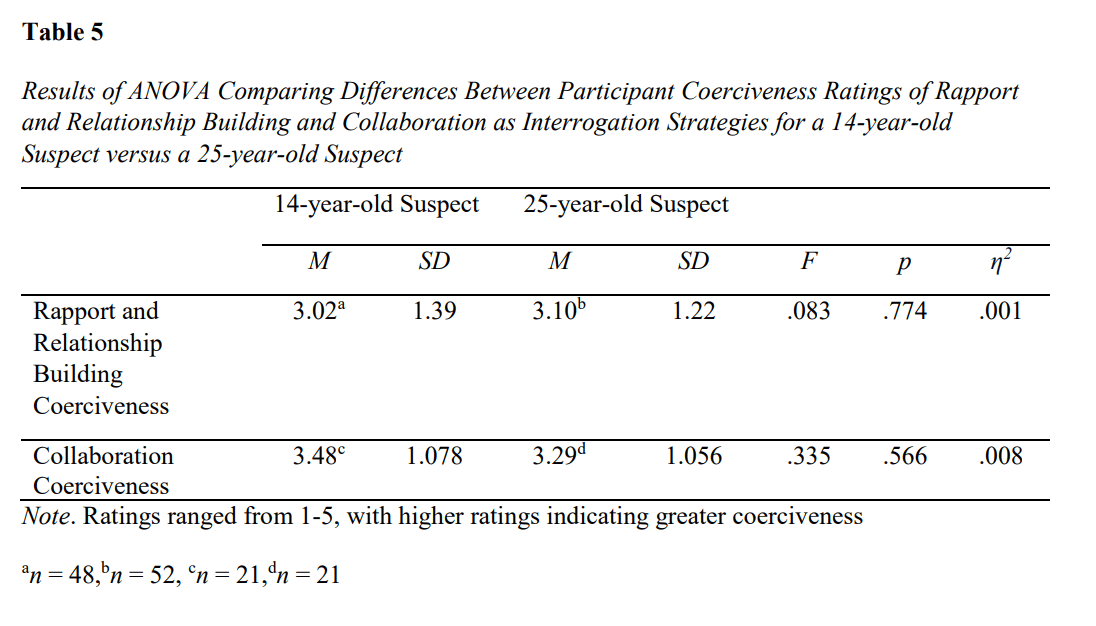

Rapport and Relationship Building Strategy Coerciveness. We used a one-way ANOVA to examine possible differences in participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the rapport and relationship building interrogation strategy. Specifically, participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of building rapport and/or a relationship with the suspect?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANOVA results are presented in Table 5. There was no statistically significant difference in the rating of the coerciveness of using rapport and relationship building as an interrogation strategy between the 14-year-old suspect condition and 25-year-old suspect condition, F(1, 98) = .083, p = .774.

Collaboration Strategy Coerciveness. We used a one-way ANOVA to examine the effect of suspect age in participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the collaboration interrogation strategy. Specifically, participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of collaboration and offering of rewards?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANOVA results are presented in Table 5. There was no statistically significant difference between the 14-year-old suspect condition and 25-year-old suspect condition in participants’ coercion ratings for the collaboration interrogation strategy F(1, 40) = .335, p = .566.

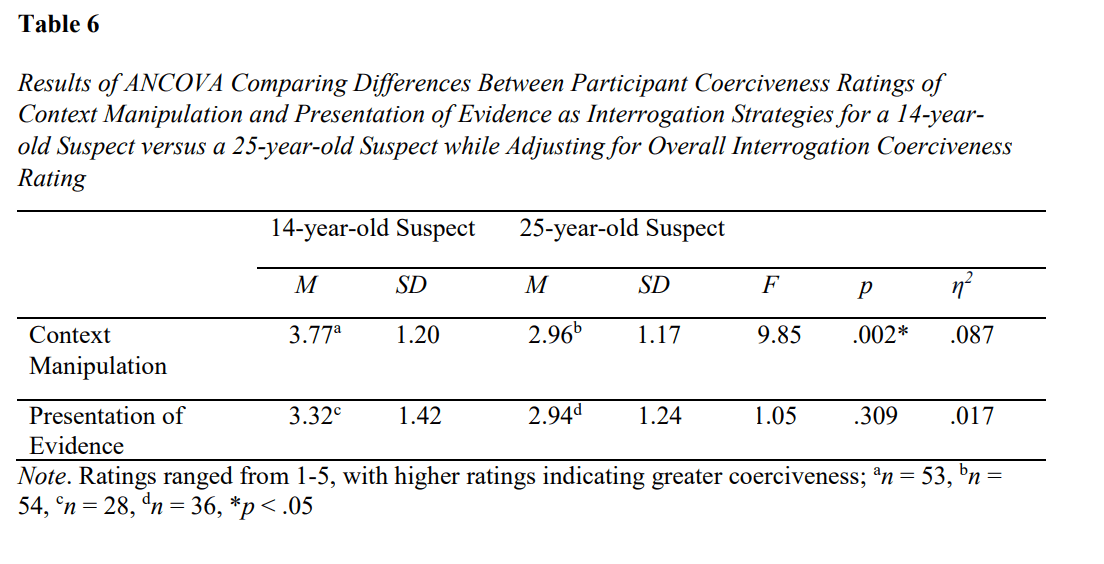

Context Manipulation Strategy Coerciveness. The results of the Pearson correlations indicated a moderate positive correlation between participants’ interrogation coerciveness rating and their context manipulation interrogation strategy coerciveness rating, r(105) = .36, p = <.001. Thus, we used a one-way ANCOVA to examine differences in participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the context manipulation interrogation strategy with participants’ overall coerciveness rating serving as the covariate by suspect age. Specifically, participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of manipulating the context of the environment where the interrogation was being held?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANCOVA results are presented in Table 6. There was a significant difference in participants’ mean context manipulation interrogation strategy coerciveness ratings while adjusting for participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating F(1, 104) = 9.85, p= .002, with the ratings of the 14-year-old defendant significantly higher (indicating greater coerciveness) than the 25-year-old condition.

Presentation of Evidence Strategy Coerciveness. In light of the moderate positive correlation between participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating and their presentation of evidence strategy coerciveness rating, r(62) = .354, p = .004, we used a one-way ANCOVA to examine participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the presentation of evidence interrogation strategy with participant age and participants’ overall coerciveness rating serving as the covariates by suspect age. Participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of presenting evidence to the suspect?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANCOVA results are presented in Table 6. There was not a significant difference between groups’ mean presentation of evidence coerciveness ratings while adjusting for participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating F(1, 61) = 1.05, p = .309.

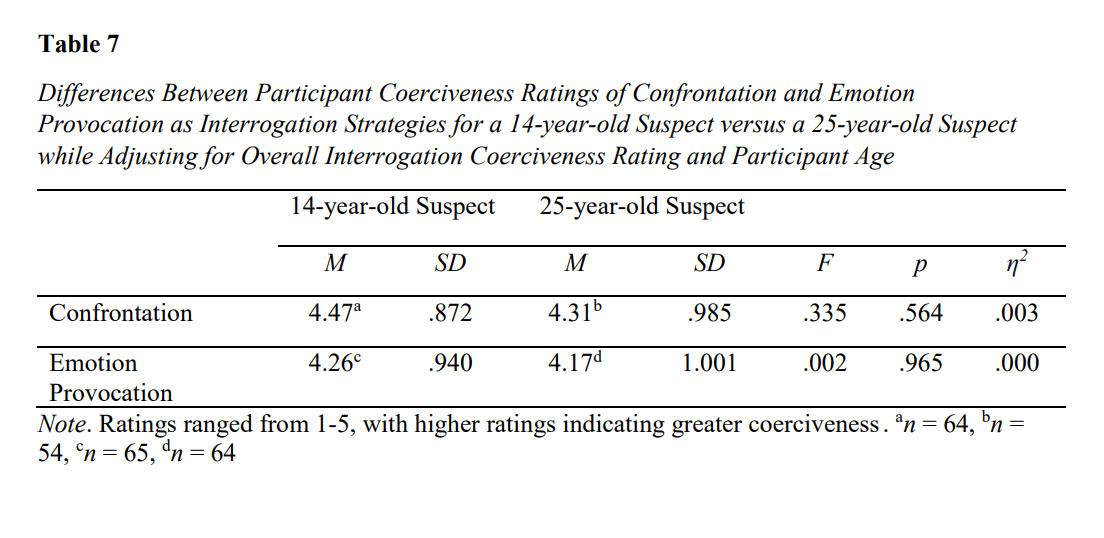

Emotion Provocation Strategy Coerciveness. In light of the moderate positive correlation between participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating and their emotion provocation interrogation strategy coerciveness rating r(129) = .52, p = <.001, and the weak negative correlation between participants’ age and their emotion provocation interrogation strategy coerciveness rating r(127) = -.29, p = .001, we used a one-way ANCOVA to examine differences in participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the emotion provocation interrogation strategy with participant age and participants’ overall coerciveness rating serving as the covariates by suspect age. Participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of provoking the suspect’s emotions?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANCOVA results are presented in Table 7. The difference between groups’ mean emotion provocation interrogation strategy coerciveness ratings while adjusting for participants’ overall coerciveness rating and participant age was not significant, F(1, 125) = .002, p = .965.

Confrontation Strategy Coerciveness. In light of the moderate positive correlation between participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating and their confrontation interrogation strategy coerciveness rating, r(126) = .62, p = <.001, and the weak negative correlation between participants’ age and their confrontation interrogation strategy coerciveness rating, r(124) = -.27, p = .003, we ran a one-way ANCOVA to examine differences in participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the confrontation interrogation strategy with participant age and participants’ overall coerciveness rating serving as the covariates by suspect age. Participants rated, “How coercive was the detectives’ use of confrontation and threats?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Not at all Coercive” and 5 indicating “Extremely Coercive.” The means, standard deviations, and ANCOVA results are presented in Table 7. There was not a significant difference between groups’ mean confrontation interrogation strategy coerciveness ratings while adjusting for participants’ initial interrogation coerciveness rating and participant age F(1, 122) = .34, p = .564.

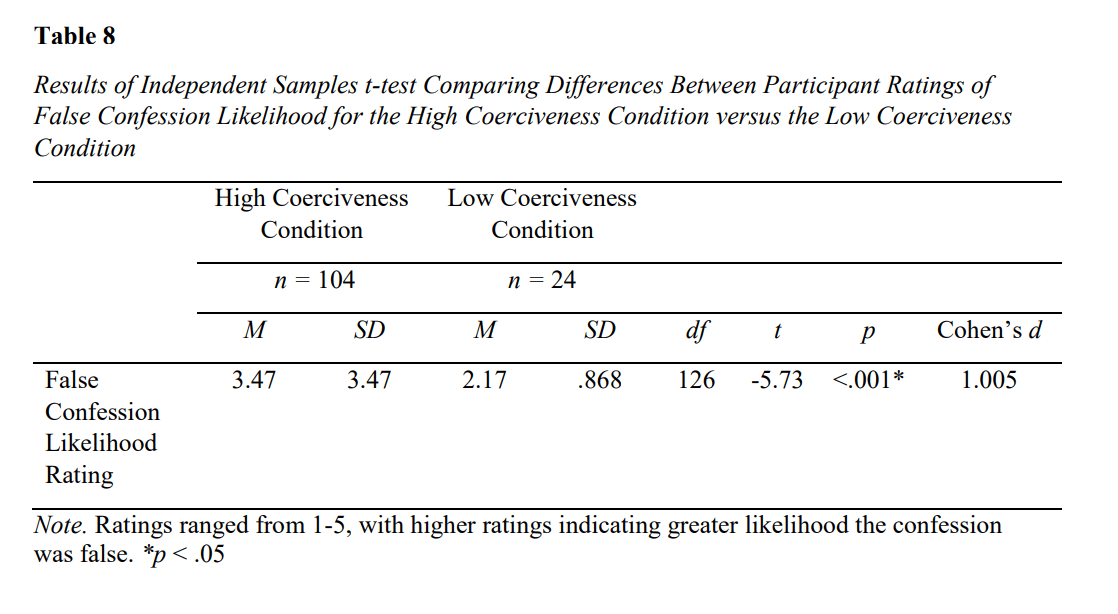

Likelihood of False Confession. We used an independent samples t-test to examine participants’ likelihood ratings that the confession was false by overall interrogation coerciveness rating (low coerciveness group vs. high coerciveness group). Specifically, participants rated, “In your opinion, how likely is it that this was a false confession?” on a 1-5 Likert scale, 1 indicating “Extremely Unlikely” and 5 indicating “Extremely Likely.” The means, standard deviations, and independent samples t-test results are presented in Table 8. The ratings of false confession likelihood did differ by participants’ overall interrogation coerciveness ratings, t(126)= -5.73, p= <.001, with ratings made by those whose overall rating of the interrogation was low having significantly lower ratings of the likelihood that the confession was false than those whose overall rating of the interrogation was high.

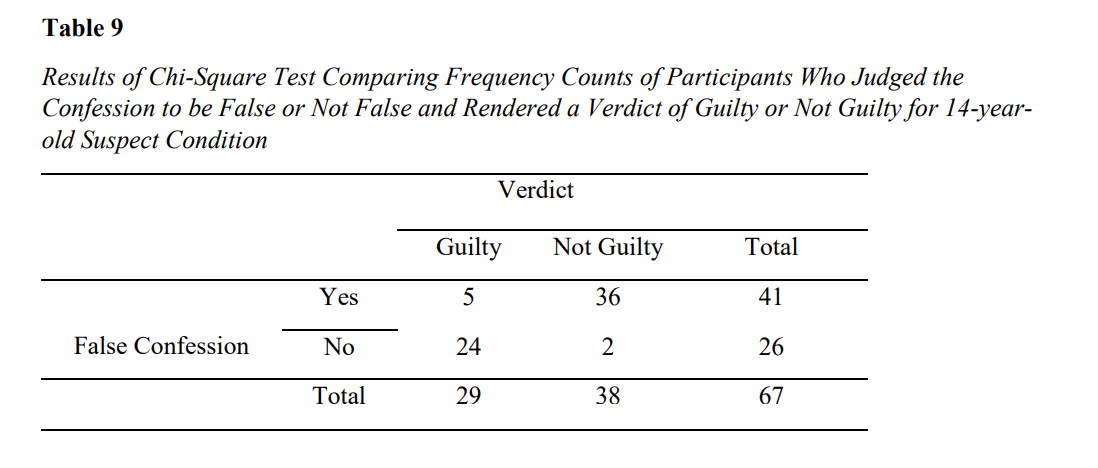

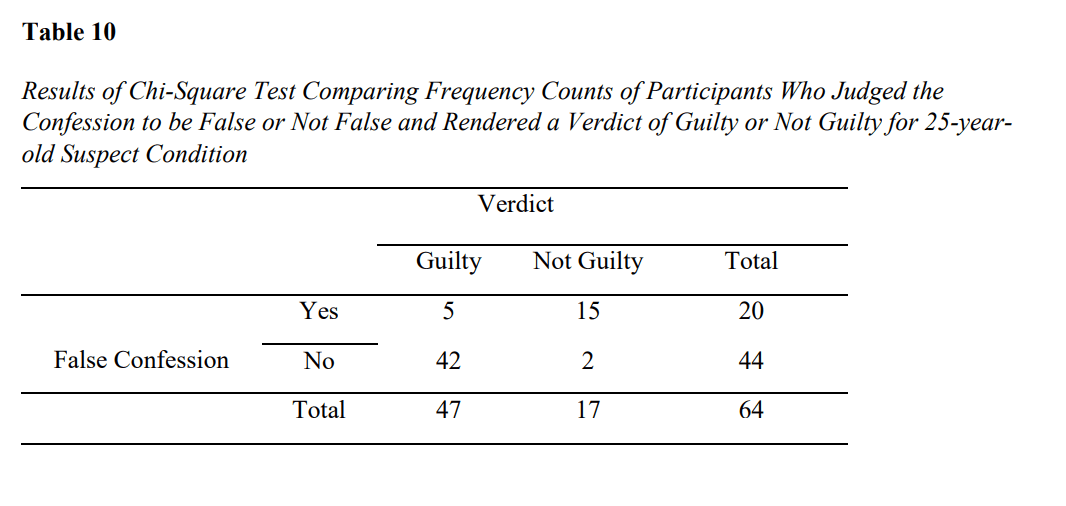

Verdict Judgement. Two (14-year-old condition and 25-year-old condition) one-sample chi-square tests were conducted to assess whether participants who judged the confession to be false were more likely to render a verdict of “Not Guilty” than participants who did not judge the confession to be false. Specifically, participants were asked “Do you think this was a false confession?” and provided “Yes” or “No” as response options. Participants were then also asked “Imagine you are a juror listening to this recording. In this role, you would have to make a decision regarding the suspect’s guilt. What would your verdict be?” and offered the response options of “Guilty” or “Not Guilty.” For the participants who evaluated a 14-year-old suspect, the chi square test was significant, χ2 (1, N = 67) = 41.60, p = < .001, indicating that those who perceived the confession to be false were much more likely to render a verdict of “Not Guilty” than those who did not perceive the confession to be false. The same pattern was seen for the 25- year-old suspect, where the chi-square was also significant, χ2 (1, N = 64) = 34.90, p < .001. The frequency counts for the juvenile and adult conditions are presented in Table 9 and Table 10, respectively.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined perceptions of confrontational interrogation strategies commonly used in American police interrogations and whether or not the participants differentially understood the coerciveness of those strategies when used with juveniles or adults, as past research in this area is mixed (Molinaro & Malloy, 2016; Najdowski et al., 2009; Najdowski & Bottoms, 2012; Redlich et al., 2008). Although there is a movement to employ less confrontational approaches to interrogations (Mindthoff & Meissner, 2023), American police departments traditionally have used strategies that many social scientists have concluded are quite coercive (Meissner et al., 2014). This has resulted in concern about the occurrence of false confessions, with organizations like the National Registry of Exonerations (2024), providing data that out of a total of 3,464 exonerations to date since 1989, 435 of those (13%) involved a false confession. Due to psychosocial maturity factors, juveniles in particular appear to be at risk for falsely confessing, with data suggesting they are approximately 3.5 times more likely to falsely confess than adults (Grisso et al., 2004). Therefore, in this study, we examined how members of the general public, who could serve as jurors, perceived interrogation strategies used in a known is a false confession; we additionally manipulated the age of the suspect in this case to determine if participants perceive commonly used strategies differently when used with juveniles versus adults.

To examine the known risk that confrontational interrogation can play in false confessions, we asked participants to envision themselves in the role of a juror. Participants then read a description of an interrogation and the suspect being interrogated, and listened to a fourminute audio of an interrogation that resulted in a known false confession. They then rated the coerciveness of the interrogation, as well as coerciveness of individual interrogation tactics and were asked to make judgments on the likelihood that the confession was false and the suspect’s guilt. We hypothesized that participants’ ratings of the coerciveness of the interaction when they were told the suspect was a 14-year-old would be higher than that of a 25-year-old suspect. We also hypothesized that participants who rated the interrogation as more coercive would rate the likelihood the confession was false as significantly higher than participants who rated the overall interrogation as less coercive. Furthermore, we hypothesized that participants who judged the confession to be false would be more likely to render a verdict of “Not Guilty” than participants who did not judge the confession to be false.

Initial analyses indicated that participants’ overall interrogation coerciveness rating significantly correlated with four of the six specific interrogation tactic coerciveness ratings: context manipulation, presentation of evidence, confrontation, and emotion provocation. This finding was unsurprising given that participants’ overall perception of coerciveness would be based on specific strategies they heard in the interrogation. More surprising was a failure to find a significant difference in the overall coerciveness rating for a juvenile versus an adult, and the weak negative correlations between participant age and two of the interrogation strategies: confrontation and emotion provocation interrogation. We used those variables as co-variates in subsequent analyses, where relevant. The specific finding that participant age, albeit weak, was negatively correlated with the confrontation and emotion provocation interrogation strategies indicates that younger participants perceived these strategies to be more coercive than older participants. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between participant age and perceptions of interrogation strategies, making this a novel and interesting finding. It is also unclear how to interpret this relationship and we wonder if it reflects generational differences regarding expectations about police interrogations. Specifically, might older individuals, who have watched dramatic depictions of interrogations that are typically quite confrontational (and, at times, illegal), find the type of interaction in the study stimulus to be typical and acceptable, whereas younger individuals, who might be more sensitive to the nature of police-suspect interactions in the wake of George Floyd and other forms of abusive police interactions, may find these interactions to be more problematic. We believe this to be an area worthy of additional research.

As mentioned, contrary to expectation, ratings of overall interrogation coerciveness by age of suspect did not significantly differ. The failure to find a significant difference may be related to the degree of coerciveness participants rated. Specifically, the mean overall coerciveness ratings of 4.12 and 3.89 for the 14-year-old suspect and 25-year-old suspect conditions, respectively, reflected a ‘Somewhat Coercive’ rating (4 = ‘Somewhat Coercive’). Therefore, regardless of age, participants felt the interrogation had coercive features. The strategies that the detectives in this interrogation used reflect the prevailing strategy used by American police officers, the Reid Technique. Despite the failure to find differences by suspect age, our finding of overall high perception of coerciveness supports not only what social scientists have concluded about the nature of that kind of interrogation, but also that the public senses this as well, regardless of suspect age.

As previously mentioned, the concern over the use of confrontational interrogations is because of its association with false confessions. Thus, we wanted to examine individuals’ overall coerciveness impression (Low vs. High) and whether these groups held different notions about whether the confession was false. It is interesting to note that fewer than 20% of the sample rated the interrogation as low on coerciveness (i.e., rated the overall coerciveness of the technique as 1 or 2). This supports the previous finding of the current study that, broadly, participants were able to correctly judge the interrogation as coercive. It is also worth noting that the distribution of overall coerciveness ratings was highly skewed, in that 18% assigned a rating of 1 or 2, and 79% provided a rating of 4 or 5, with only three participants (2%) assigning the rating of ‘Neither coercive nor Not Coercive.’

Notably, although the majority of the sample judged the coerciveness of the interrogation to be high, the rating related to the likelihood of a false confession, although significantly different between groups, was low: respective mean ratings were 2.17 (2 indicating a rating of ‘Unlikely’) for those who gave a low rating of coercion and 3.47 (3 indicating ‘Neutral’) for those who rated the coerciveness as high. Furthermore, although the majority of participants (94.6%) across both conditions rated the interrogation as coercive to some degree (slightly, somewhat, extremely), judgments that the confession was false were much lower: 61% and 31% of participants in the juvenile and adult condition, respectively. These findings suggest that laypeople’s ability to pick up on coercion alone may not be sufficient to understand the associated risk coercion poses for falsely confessing. This aligns with experimental studies that suggest participants harbor naiveté towards the degree of risk interrogation coercion poses for falsely confessing (Blandon Gitlin et al., 2011; Henkel et al., 2008; Leo & Liu, 2009) and that laypeople are generally unable to distinguish between true and false confessions (Kassin et al., 2005).

From a more promising perspective and one worthy of mentioning due to the study’s primary focus on age was that the percentage of participants in the adolescent condition who perceived the confession to be false (61%) was nearly double that of the percentage in the adult condition (31%). This finding suggests that participants do perceive juveniles to be more vulnerable to false confession than adults. In addition, of the participants who identified the confession as false, 87.9% and 75% rendered a verdict of “not guilty” in the juvenile and adult condition, respectively. Moreover, 43% of the total juvenile sample judged the suspect to be guilty, which is in stark contrast to past studies investigating laypeoples’ perceptions of juvenile false confessions where 75% (Grove & Kukucka, 2021), 76% (Redlich et al., 2008) and 80% (Molinaro & Malloy, 2016) of participants misjudged the juvenile suspect as guilty. It is unknown why the current study’s guilt finding was so different from that of previous studies. However, the studies previously mentioned did not ask participants about their perceptions on the confession being false like the current study did, which might explain the differences in ratings. That is, asking someone to make a judgment about the nature of the confession could introduce doubt that might alter their overall judgment about culpability.

We also asked participants to evaluate six interrogation techniques used in the Reid Technique to investigate whether participant perceptions of the coerciveness of these techniques differed by suspect age. Aside from the context manipulation interrogation technique, there were no statistically significant differences in participant coerciveness ratings for the remaining five (rapport and relationship building, collaboration, confrontation, emotion provocation, and presentation of evidence) interrogation techniques when comparing the 14-year-old suspect condition to the 25-year-old suspect condition. Descriptive statistics indicate that regardless of age, participants rated the confrontation and emotion provocation strategies as coercive (mean ratings ranged from 4.17 to 4.47, with a rating of 4 indicating ‘Somewhat Coercive’), whereas participants expressed an indifferent attitude toward the other strategies: rapport and relationship building, collaboration, and presentation of evidence interrogation, as mean ratings for these ranged from 2.94 to 3.48, with a rating of 3 indicating ‘Neither Coercive nor Not Coercive.’

Our descriptive statistics related to the coerciveness ratings of different interrogation strategies aligns with past research findings (Mindthoff et al., 2018). Of particular relevance is the finding that laypeople tend to rate the relationship and rapport interrogation strategy as the least coercive of strategies utilized by law enforcement. For example, in the present study this strategy had the lowest mean coerciveness rating out of the six strategies, which is consistent with the findings of Mindthoff et al. (2018), which also examined participant perceptions of coerciveness of several interrogation methods. The theme that laypeople are less likely to perceive the relationship and rapport building interrogation strategy as coercive as other potential strategies is concerning given research findings of how often the technique is utilized. For example, several studies (Kassin et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2016; Vallano et al., 2015) utilizing investigator respondents and/or analysis of interrogation recordings found rapport and relationship building to be the most frequently used strategy and one that is favored by American investigators. This is perhaps unsurprising given the Reid Technique endorses this strategy as the foundation for the first phase of an interrogation. Although not inherently coercive, Reid’s (2000) description of rapport as “a relationship marked by conformity” underscores the true nature of how this strategy was intended to be utilized in American interrogations. Further emphasizing the concern of participants’ perception of the relationship and rapport building interrogation strategy is how it is utilized to enhance the effectiveness of other coercive techniques. As described in Deslauriers-Vain and St. Yves (2006), the rapport and relationship interrogation strategy can function independently to produce confessions, whereas the other interrogation strategies are often unsuccessful in the absence of rapport building. Kelly et al. (2013) took this idea a step further in their theoretical model of interrogation methods and designated the rapport and relationship interrogation strategy as the focal point from which all other interrogation strategies can flow. The authors further described the strategies as interacting in an interdependent manner, noting how investigators will return to the focal point of basic rapport and relationship building strategy when the other domains of strategies are unsuccessful in producing the intended outcome of the interrogation (Kelly et al., 2013). Taken together, this information in light of the findings of this study suggest that laypeople significantly discount the influence of the rapport and relationship building strategy and potential jurors would benefit from the dissemination of social science research to improve the accuracy of their perceptions in legal cases where a confession is being questioned.

It is interesting to note that the one significant interrogation technique difference between groups was the technique that included a visual depiction, as the context manipulation technique was described to the participants via a photo of a small, windowless brick room with a table and two chairs sitting opposite one another (see Appendix B). Given that this was the only interrogation strategy where a visual aid was included, it could be that the photo increased the salience of this strategy to participants in the juvenile condition.

Although five out of the six interrogation strategies did not yield statistically significant differences by age of the suspect, features of the ratings themselves are notable. Similar to the rapport and relationship strategy, the mean rating provided by participants across conditions for the collaboration and presentation of evidence strategies also fell toward the midpoint (“neither coercive nor not coercive”). In contrast, participants across conditions provided a mean rating of “slightly coercive” for the confrontation and emotion provocation strategies. Together, these responses indicate that some interrogation strategies more than others, regardless of age, emerge as more coercive to participants. The participants’ underestimate of the degree to which the collaboration and presentation of evidence strategies exploit juvenile vulnerabilities is one worth discussing in the context of developmental cognitive neuroscience to underscore why this finding is problematic. For example, the promise of rewards and increased chance of leniency inherent in the collaboration strategy exploits the limited foresight and prioritization of short-term benefits over long-term consequences that characterizes the adolescent time period (Davis & Leo, 2012; Steinberg et al., 2009). Similarly, the goal of instilling hopelessness in the presentation of evidence strategy, where escape becomes a prevalent solution to the interrogation, exploits the hypersensitive emotional parts of an adolescent’s brain which makes them more likely to engage in behaviors that will end the interrogation even to their own detriment (Cleary, 2017; Drizin & Colgan, 2004).

In conclusion, the vast majority of participants (80%), regardless of suspect age, identified the interrogation as coercive. However, it appears that participants’ knowledge of the risk coercion poses for falsely confession is limited, as even amid a high rate of coercion identification, the ratings for the likelihood of the interrogation being false were low. In fact, only 61% and 31% of participants in the juvenile and adult conditions, respectively, rated the confession as being false. Although there appears to be a disconnect in the translation between degree of coercion and risk for false confession, the two-fold increase observed between the juvenile and adult false confession judgements provides support that participants do recognize youth as a specific vulnerability factor for falsely confessing. Our hypothesis that participants who judged the confession to be false would be more likely to render a verdict of “not guilty” was supported, across both conditions, indicating that participants are able to evaluate the nature of the confession when asked to render a verdict. Overall, there was a failure to find differences between the juvenile and adult suspect conditions for coerciveness ratings on five of the six interrogation strategies. The context manipulation strategy was found to be statistically different between groups and this was the one strategy where a picture accompanied the description, suggesting that visual aspects of an interrogation may be useful in aiding potential jurors’ in evaluating different interrogation strategies. The vast majority of our evidence here does not support the widely held legal assumption that age and interrogation strategies are within the “common knowledge” of laypeople who could be potential jurors. Our findings do support the recommendations asserted by other social scientists that expert testimony on these risk factors would be beneficial to the judicial system.

Limitations. There are several factors to consider when interpreting the findings of the current study. First, we were unable to manipulate the voice of the audio recording for the 14- year-old suspect condition to make it sound more stereotypically young. To increase the likelihood that participants perceived the audio to represent the voice of a 14-year-old, a disclaimer was added to the end of the interrogation audio description that read, “You will be listening to a real interrogation, however since this interrogation involved a juvenile, the audio has been muffled and distorted in various ways and as a result, may not sound authentic.” Although we took measures to present credible stimuli, the age manipulation may not have been as prominent as the researchers had hoped. This possibility is supported by the rates at which participants misremembered the suspect’s age; half of the participants did not correctly identify the juvenile suspect as a juvenile. Although we only included those individuals who correctly reported the age of the suspect (as presented in the stimulus material), the high rate of misidentification suggests that the salience of age may not have been high. Qualitative data gathered from one participant in the 14-year-old condition where they correctly identified the age of the suspect provided in the survey but commented on how they perceived the suspect to be older appears to highlight this limitation. The researchers are unsure of how many participants harbored the same thought but didn’t comment on it, which may account for the lack of differences found between conditions.

Although steps were also taken (i.e., utilizing Prolific) to diversify the study sample, the sample still remained overwhelming White (69%), which limits the generalizability of these findings as the demographic makeup of the sample was not representative of U. S. citizens as a whole. Related to this limitation is that the researchers did not analyze whether respondent race impacted the perception of the interrogation in the current study. We are living in a social climate where increasing attention is being brought to the racial injustices in the U.S. criminal justice system. Therefore, additional information on whether the race of the participant influences perceptions of law enforcement interrogations appears to be an avenue worthy of further inquiry.

It is also worth noting the experimental context of this study and the potential order effects of the survey questions. For example, the first question participants were asked after hearing the interrogation audio was whether they perceived the confession to be false. We question whether this may have primed participants in some way to influence their responses in later questions. We are unsure the extent to which the survey question order may have influenced the results found here. While the experimental nature of the study brings advantages, it is an artificial context and the findings found here do not tell us what people in an actual jury would think or the judgments they would make. The extraneous variables present in a jury trial (e.g., stress, individual biases, presentation of evidence, etc.) are plenty and the broad scope of understanding how each of these factors interacts with one another to influence jurors’ perceptions in the real-world is not captured in the artificial context of experimental research. Furthermore, although we attempted to gather data from participants who would be considered jury-eligible, these criteria were not exhaustive. Thus, the generalizability of these findings to potential jurors is limited.

Future directions. As the ultimate decision makers in many trials related to a suspect’s innocence or guilt, future studies should continue to seek potential jurors’ perceptions of adolescence as a risk factor for falsely confessing and various interrogation tactics currently utilized in American interrogations. First and foremost, gathering data from jurors who have been selected for jury duty might allow for an examination of a limitation mentioned above regarding the artificial context of the present study and to extend the generalizability of this study’s findings. As mentioned previously, a unique finding of this study was the small, negative correlation between participant age and the emotion provocation and confrontation strategies. Notably, to our knowledge, prior research has not explored the association between participant age and perceptions of interrogation strategies. It is plausible that there are generational differences in what is viewed as acceptable in police-suspect interactions. This presents a compelling area for further investigation.

In the present study, age was only one factor we chose to manipulate and investigate. However, there are additional factors that are known to influence laypeople’s’ perceptions of suspects and future research would benefit from further exploration of these risk factors. For example, research suggests that suspect race impacts participant perceptions of suspects and of particular relevance to the current study is that youth of color tend to be perceived as older than their actual age when compared to their White counterparts. Additional investigation of how various risk factors (e.g., age, race, cognitive abilities) interact with one another to influence laypeople’s perception of interrogation strategies appears to be a potentially fruitful avenue of research.

Finally, in the present study, we did not use expert analysis of the presence or absence of the interrogation strategies employed in the study stimulus. Therefore, we don’t know if the participants correctly identified the presence of problematic strategies. An explanatory analysis of the frequency with which participants identified the interrogation strategies demonstrated notable variance in identified frequency, depending on the strategy. As the expectation in the courtroom is for jurors to be able to recognize these strategies on their own, future research would benefit from independent raters considered to have expert knowledge on interrogations verify the frequency interrogation strategies are used in an interrogation and compare these expert ratings to laypersons’ ratings.

Appendix A

Link to Audio Recording

https://www.dropbox.com/s/sklud8j6gh3ha9p/Audio%20A.wav?dl=0

Appendix B

Study Descriptions

Description 1

Please read carefully.

Imagine that you are a juror. In this role, a court asks you to consider evidence that is presented to you to make judgments about a defendant’s guilt. In a moment, you will listen to an audio recording from a real case, in which two detectives are questioning a suspect. The picture below shows the room where the interrogation took place. Although the clip you will listen to is four and half minutes long, it was compiled from a single interrogation session that lasted for a period of 7 hours. The suspect is a 25-year-old male named Matt, who is being questioned about the murder of his aunt and uncle. While listening to the audio recording, a transcript of the recording will appear on your screen, to ensure you can understand what is being said. Following the recording, you will be asked several questions about the case, including making a determination about whether or not Matt committed the crime he is accused of. You will also be asked to answer general questions regarding your perception of the interrogation process.

*Note: Explicit language and description of events that some may find unsettling are present in this recording. Please exit the study now, or at any time during the study, if you no longer wish to participate.

Study Descriptions

Description 2

Please read carefully.

Imagine that you are a juror. In this role, a court asks you to consider evidence that is presented to you to make judgments about a defendant’s guilt. In a moment, you will listen to an audio recording from a real case, in which two detectives are questioning a suspect. The picture below shows the room where the interrogation took place. Although the clip you will listen to is four and a half minutes long, it was compiled from a single interrogation session that lasted for a period of 7 hours. The suspect is a 14-year-old male named Matt, who is being questioned about the murder of his aunt and uncle. While listening to the audio recording, a transcript of the recording will appear on your screen, to ensure you can understand what is being said. Following the recording, you will be asked several questions about the case, including making a determination about whether or not Matt committed the crime he is accused of. You will also be asked to answer general questions regarding your perception of the interrogation process. You will be listening to a real interrogation, however since this interrogation involved a juvenile, the audio has been muffled and distorted in various ways and as a result, may not sound authentic.

*Note: Explicit language and description of events that some may find unsettling are present in this recording. Please exit the study now, or at any time during the study, if you no longer wish to participate.

Appendix C

Transcript of Audio Recording

D1 = Detective 1

D2 = Detective 2

S = Suspect

D1: This is considered a non-custodial interview. You're free to leave at any time.

S: Well, I'm here to cooperate with you gentlemen.

D1: Okay, and that's just for the record, so you don't think that you're trapped here. And if at any time, you go, "I'm not happy and I don't want to be here," you can leave.

S: Okay.

D1: What kind of person do you think goes into someone's house and shoots somebody and takes their life?

S: A sicko. A sick person. That's what I think. But I don't know. I mean, it's -- We're like you. We want to know the who, what, when, why and how and who.

[Time passes]

S: I didn't have anything to do with this.

D1: You did.

S: I did not.

D1: You did.

S: I did not.

D1: You did.

S: No, I didn't.

D1: I'm sorry, you did.

D1 and D2: Come on, Matt. - Come on, Matt. You're thinking too hard. You've got your mind spinning, going, "I'm trying to get out of this. What do I say to these guys?" We've had so many people sitting in that chair, okay, that think that they're smarter than us, and you're not.

S: No.

D1: Okay

S: No, I'm dumb as a brick.

D1 and D2: No, you're not dumb as a brick, okay? You made a mistake. You fucked up. You did. You fucked up, and now you've got to pay for it.

D1: Do you consider yourself a man? Then stand up. No, stand up and be a man, okay? Own up. Own up for what you've done. Do you understand? You shake your head at me and you look at me. I just want to make sure you understand.

S: I'm trying to.

D1: Okay, then speak up and tell us. If you don't admit to me exactly what you've done, I'm gonna walk out that door, and I'm gonna do my living best to hang your ass from the highest tree. You're done. I'll go after the death penalty. I'll push, I'll push and I'll push until I get everything I need to make sure you go down hard for this. There is no second chance 'cause I'll look at you and go piss on you.

7 hours of questioning continue…

D1: Let's take this in baby steps, all right? Let's try to make this as simple as possible. Where did you get the shotgun from?

S: The only one I have is locked up in my dad's gun safe, and I don't even know where the keys are for it.

D1: Man, I'm trying to help you piece this together 'cause we already know the truth, man. Baby steps. Start to finish. The truth is you got a gun. Right or wrong?

S: Right.

D1: And you took that gun back to your Uncle Wayne and Aunt Sharmon's house, right? Right or wrong? Come on, man.

S: Right.

D1: And you walked upstairs in their house after hours. - Right or wrong?

S: Right.

D1: And you walked in with that shotgun and you saw they were laying in bed. Right or wrong?

S: Right, I guess. Right.

D1 and D2: Right. And you fired a shot - at your Uncle Wayne.

S: Right.

D1: What happened next? I want you to tell me.

S: (inaudible)… Don't remember.

D1: You don't remember? But you got pretty close to Aunt Sharmon, didn't you?

S: Right, I guess. I don't know, um –

D1: All that rage running through you. –

S: Right.

D1: And you fired a shot to shut her up. Is that right? I need you to say it out loud, buddy.

S: Yes, sir.

D1: It's all right, buddy. You started to say it. Come on, let it go.

S: Then I pulled that trigger and shot her. And then she screamed more. And then I just—

D1: You just what, buddy?

S: Put the gun to her face and blew it away. –

D1: Okay.

S: And then as I headed out, I just stuck it to him and blew him away.

D1: Now tell me how you feel.

S: Like shit.

D1: You're breathing a little easier than you were before.

S: Yeah. Doesn't make anything…

D1: No, it doesn't make it better.

S: No.

D1: It ain't gonna bring 'em back.

S: No. I fucked up

Appendix E

Manipulation Checks

Thinking back to the audio recording:

4. In the description you read, what was the suspect’s age? (Write Response)

5. What was the name of the suspect in the audio recording?

a. I don’t know

b. John

c. Matt

d. No name was mentioned

6. How many detectives questioned the suspect in the audio recording?

a. 1

b. 2

c. 3

7. How long did the full questioning last?

a. 2 hours

b. 5 hours

c. 7 hours

Demographic Form and General Information Questionnaire

1. Age

a. Write in: ____

2. Assigned sex at birth:

a. Male

b. Female

c. Prefer not to respond

3. Current gender identity:

a. Male

b. Female

c. Transgender male to female

d. Transgender female to male

e. Gender non-conforming

f. Write in: __________________

g. Prefer not to respond

4. What is your race/ethnicity?

a. American Indian

b. Asian

c. Black/African American

d. Hispanic American or Latino/a

e. Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

f. White/European American

g. Multiracial: _______

h. Write in: ___________________

i. Prefer not to respond

5. Current Year in College

a. 1 st year

b. 2 nd year

c. 3 rd year

d. 4 th year

e. Graduate School

6. Major Area of Study

a. Write in: ______

7. Do you have any immediate or extended family members who are employed in law enforcement?

a. Yes

i. If yes, in what area? __________

b. No

8. Do you want to work in criminal justice/law enforcement?

a. Yes

b. No

c. If yes, in what capacity?

9. What political affiliation best describes you?

a. Democratic

b. Republican

c. Independent

d. Other: ___________

e. Prefer not to respond

10. How would you describe the income level of your family of origin?

a. Very low

b. Low

c. Middle

d. Upper-Middle

e. Upper

Summary

Title: Perceptions of Interrogation Tactics in Juvenile False Confessions

Problem: It has been long recognized that people can and do make false confessions and interrogation strategies, particularly those involved in the Reid Technique (Inbau et al., 2013), have been implicated in false confessions (Meissner et al., 2014). Another risk for falsely confessing is juvenile status, due to the neurological (Steinberg et al., 2009; Steinberg et al., 2017) and social immaturity (Cleary, 2007) of adolescence that significantly hinders effective decision-making during this developmental period, particularly under stressful conditions. Current legal practices, like use of the Reid Technique with juveniles, run the risk of exploiting these developmental vulnerabilities, yet continues to be utilized with juveniles. Comparing the known proportion of juvenile false confessions (47%) to the known proportion of adult false confessions (13%) in exoneree cases illustrates this point (Grisso et al., 2004). Broadly, despite age and interrogation strategies being recognized by social scientists as significant risk factors for falsely confessing, these vulnerabilities have long been described in the justice system to be within the “common knowledge” of laypeople (Chojnacki et al., 2009), despite most experimental research indicating otherwise (Chojnacki et al., 2009; Mindthoff et al., 2018; Molinaro & Malloy, 2016; Redlich et al., 2008). To this writer’s knowledge, there are no studies to date examining juror-eligible participants’ ability to recognize the coerciveness of commonly used interrogation tactics with juvenile suspects. To bridge this gap, we compared participants’ judgments of an interrogation that they were told was a juvenile suspect versus an interrogation of an adult suspect.

Method: A final sample of 131 participants completed study measures online after being recruited via a university participant pool and Prolific. Participants listened to a four minute, 28- second audio recording of an actual interrogation that resulted in a real false confession. Participants were randomly assigned to a condition that indicated the suspect was a 14-year-old or a 25-year-old and then completed a 31-question survey regarding their perceptions of the interrogation. For this study, we compared participants’ judgments of an interrogation that they were told was a juvenile suspect versus an interrogation of an adult suspect. We also compared participants’ ratings of the likelihood the confession was false by degree of interrogation coerciveness identified, as well as how participants’ perception of the veracity of the confession influenced their verdict judgement. A combination of statistical analyses was utilized to analyze the data, including independent samples t-test, ANOVAs, ANCOVAs and chi-square tests. Findings: Overall coerciveness ratings of the interrogation did not differ by suspect age t(129) = 1.13, p = .261, nor were there significant differences found between conditions for the rapport and relationship building F(1, 98) = .083, p = .774, collaboration F(1, 40) = .335, p = .566, presentation of evidence F(1, 61) = 1.05, p = .309, emotion provocation F(1, 125) = .002, p = .965, or confrontation F(1, 122) = .34, p = .564 interrogation strategies. The only significant finding between the juvenile and adult condition of the six interrogation strategies was for the context manipulation strategy F(1, 104) = 9.85, p = .002, with the ratings of the 14-year-old defendant significantly higher (indicating greater coerciveness) than the 25-year-old condition. Regarding participants’ perception of the likelihood the confession was false, there was a significant difference in participant likelihood ratings by participants’ overall coerciveness ratings t(126)= -5.73, p = <.001, with ratings made by those whose overall rating of the interrogation was low having significantly lower ratings of the likelihood that the confession was false than those whose overall rating of the interrogation was high. The results also indicate that participants who judged the confession to be false were significant more likely to render a verdict of Not Guilty than participants who did not perceive the confession to be false for both the juvenile suspect condition χ2 (1, N = 67) = 41.60, p = < .001 and adult suspect condition χ2 (1, N = 64) = 34.90, p < .001.

Implications: The vast majority of participants (80%), regardless of suspect age, identified the interrogation as coercive. However, it appears that participants’ knowledge of the risk coercion poses for falsely confession is limited, as even amid a high rate of coercion identification, the ratings for the likelihood of the interrogation being false were low. In fact, only 61% and 31% of participants in the juvenile and adult conditions, respectively, rated the confession as being false. The two-fold increase observed between the juvenile and adult false confession judgements provides support that participants do recognize youth as a specific vulnerability factor for falsely confessing, however, the failure to find differences between the juvenile and adult suspect conditions for coerciveness ratings on five of the six interrogation strategies indicates participants do not recognize how these strategies in particular contribute to youth vulnerability for falsely confession. The vast majority of our evidence here does not support the widely held legal assumption that age and interrogation strategies are within the “common knowledge” of laypeople who could be potential jurors. Our findings do support the recommendations asserted by other social scientists that expert testimony on these risk factors would be beneficial to the judicial system.