Abstract

Misuse and accidental overdoses attributed to stimulants are escalating rapidly. These stimulants include methamphetamine, cocaine, amphetamine, ecstasy-type drugs, and prescription stimulants such as methylphenidate. Unlike opioids and alcohol, there are no therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat stimulant-use disorder. The high rate of relapse among this population highlights the insufficiency of current treatment options, which are limited to abstinence support programs and behavioral modification therapies. Here, we briefly outline recent regulatory actions taken by FDA to help support the development of new stimulant use disorder treatments and highlight several new therapeutics in the clinical development pipeline.

All facets of illicit drug use are on the rise globally. In 2021, 296 million people worldwide had used a nonprescription drug with the potential for misuse (addictive) in the past 12 months, which is a 23% increase from 2011 [1]. While nonmedical opioid use contributed the most heavily to severe illicit drug-related harm (∼60 million people), stimulant misuse is rapidly escalating. In 2022, 36 million people reported past-year use of amphetamines, 22 million reported using cocaine, and 20 million reported using ecstasy-type substances (e.g. 3, 4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine [MDMA]). Among these individuals, 35 million people met the criteria for a stimulant-use disorder (StUD). Moreover, nearly half of all individuals who use amphetamine-like substances are women (45%), which is proportionately higher than for every other illicit drug class (opioids: 25%, cocaine: 27%, cannabis: 30%, and ecstasy-like: 38%;). Only nonmedical prescription opioid use outweighs the percent of women using amphetamine-like substances, at 47%.

An additional area of concern is the misuse of prescription stimulants, such as amphetamine and dextroamphetamine combinations (Adderall and Dexedrine), methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin, Concerta), and methamphetamine (Desoxyn). These are commonly prescribed for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy and, occasionally, for treatment-resistant depression and obesity. The number of ADHD diagnoses is increasing across all ages, particularly in adults. With this increase, misuse is inevitably on the rise. In 2018, 16 million individuals were prescribed a stimulant, and an estimated 5.4 million misused one. In 2022, misuse was reported to be greatest among college-age individuals (age: 18–25) at 3.7%. These individuals almost exclusively misused prescription stimulants as a study aid with the goal of reducing fatigue and increasing focus.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) criteria states that StUD is diagnosed when an individual exhibits at least 2 of 11 symptoms over a 12-month period across 4 different categories: 1) loss of control, 2) risky use, 3) social problems, and 4) drug effects. Severity of the diagnosis is based on the number symptoms displayed: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5), and severe (6 or more). Interestingly, nearly half of all individuals with methamphetamine- or cocaine-use disorder qualify as severe at 48.8% and 46.6%, respectively. There is a strong current focus on opioids in the United States because of the high rate of fatal overdoses. However, it is worth noting that ten times more people used a stimulant in 2021 than heroin (10 vs 1 million). While this likely highlights the infiltration of fentanyl, the high rates of stimulant use cannot be dismissed. Indeed, in 2022, 35,000 people died of a stimulant overdose in the United States, and 71.2% of overdoses across 28 states and DC were associated with the particularly dangerous combination of an opioid and a stimulant. Consistent with this, polydrug use is extremely common among individuals who use stimulants and clinicians in the United States report that methamphetamine use can derail what would otherwise be successful treatment for opioid-use disorder. Treatment of StUD is particularly challenging because, unlike opioid- and alcohol-use disorders, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies. Thus, to better meet the needs of a growing global, often polydrug-use problem, there is a critical need for therapeutics that target StUD.

FDA regulatory actions taken to support development of stimulant-use disorder treatments

Remarkable advances have been made in understanding the neurobiology of StUD, leading to a long list of potential therapeutic targets. Unfortunately, this disorder is a particularly extreme example of the gap that often exists between preclinical research and medication development. Specific reasons for this with regards to StUD include a lack of interest from sources of private investment, as well as pharmaceutical companies that might otherwise be excellent licensing partners. This is attributed to both the perceived high-risk nature of working with this population (e.g. poor patient compliance; insurance coverage concerns) and existing regulatory challenges, such as the expectation of complete abstinence as the primary measure of efficacy. Despite this, it has become undeniable that this is a very large and rapidly growing population in great need with high rates of insurance coverage (∼75%) and protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Furthermore, the cost of a medication is likely to be far lower than the cost of repeated stays in recovery programs and more easily adhered to by this population than many behavioral modification therapy regimens, which should garner the support of payers.

To help alleviate some of the pressures limiting development of StUD therapeutics, FDA held a patient-focused drug development (PFDD) meeting in October 2020 specifically dedicated to this disorder. A PFDD is designed to ensure the patients’ perspectives and needs are being incorporated into drug development and evaluation. In this meeting, patients and providers articulated the need to define success as use reduction, rather than complete abstinence, arguing that there are clear health and economic benefits to a harm reduction approach. Then, in October 2023, the FDA released draft guidance for developing drugs for the treatment of StUD. This included recognition that there may be appropriate measures to demonstrate clinical benefit other than complete abstinence, such as an extension in the number of nonuse days for an individual. In addition, the draft guidance encourages sponsors to determine and clearly focus on a phase of the use disorder (e.g. active use versus relapse).

Stimulant-use disorder treatments in the clinical development pipeline

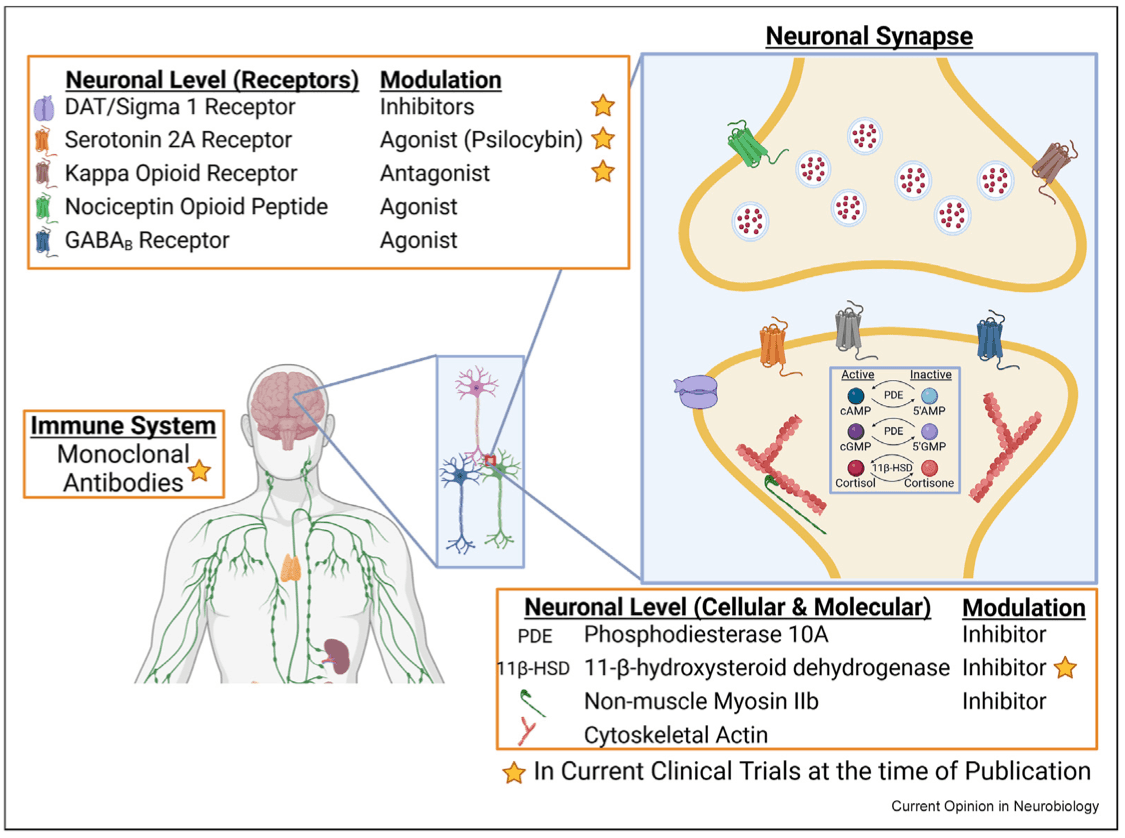

Currently, the most effective treatment course for StUD is a combination of contingency management (CM) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). While treatment with CM and CBT have yielded short-term and moderate effects in reducing use relapse, the addition of medications, similar to treatment methods utilized for opioid use disorder, has the potential to yield even better outcomes. Currently there are no approved therapeutics for StUD, though several treatments are being explored in the clinical development pipeline that cover a range of mechanisms and use both small-molecule and biologic modalities. Here, we highlight several of these (Figure 1).

Catecholamines

One of the main characteristics of stimulants is their interference with catecholamine reuptake, particularly dopamine, resulting in significant accumulation in the synaptic cleft. Therefore, it is not surprising that targeting this process is a treatment line of inquiry with the longest history for StUD. However, to date, these programs have not been successful. This is, at least in part, due to the inherent challenges of manipulating the catecholamine system, including potential drug–drug interactions and anhedonia, which can lead to safety issues and poor patient compliance, respectively. Recently, interest in the dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) as a therapeutic target has been rekindled by studies of the molecular chaperone sigma-1 receptor, which binds to DAT and regulates dopamine signaling. While still at the early stage of lead optimization, Sparian Biosciences is developing a combined DAT inhibitor and sigma-1/-2 antagonist that is reported to prevent methamphetamine and cocaine self-administration without interfering with physiologic transport of dopamine in preclinical studies.

Opioid system

One of the most promising clinical trial results to date for StUD comes from a multisite, two-stage Phase 3 clinical trial with a combination of extended-release injectable naltrexone and oral extended-release bupropion (ADAPT-2, NCT03078075). Naltrexone is a combination opioid-receptor antagonist (mainly mu with weak kappa [KOR] and delta effects), and bupropion is an atypical DAT and norepinephrine-transporter inhibitor. Six weeks of combination treatment reduced methamphetamine-positive urine samples over a 12-month period. This highlights the therapeutic potential of the opioid system for StUD, which has been investigated in a number of preclinical studies. For example, KOR activation on dopaminergic neurons can modulate dopamine release and potentiate stress-induced cocaine-conditioned place preference. Furthermore, PET imaging of individuals with cocaine-use disorder demonstrated greater KOR agonist binding under stress-induced cocaine self-administration conditions, as compared to precocaine choice baseline images. While the ADAPT-2 trial highlights the potential for KOR inhibition, it is a complicated target as there is also evidence indicating that, depending on the timing of treatment, enhancing KOR activity could also potentially facilitate treatment of cocaine-use disorder.

Nociceptin opioid peptide (NOP) may also prove to be a therapeutic target. Buprenorphine, a μ- and NOP-opioid receptor agonist, has already been approved for opioid-use disorder, and preclinical studies indicate that coactivation of these receptors inhibits acquisition of methamphetamine self-administration and reduces context and drug-induced seeking behavior. Furthermore, NOP is significantly increased in individuals with cocaine-use disorder, compared to that in controls, after 2 weeks of abstinence. Phoenix PharmaLabs is currently developing a novel NOP-targeting compound, PPL-138, as a nonaddictive analgesic, but it may also have potential for the treatment of StUD.

GABA

Stress can serve as a major motivating factor in StUD. To that end, Embera NeuroTherapeutics has been exploring the potential of targeting anxiety by simultaneously modulating two neural processes—the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and GABA transmission. In support of focus on the latter, methamphetamine and cocaine training decrease expression of GABAB receptors in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. When reversed through upregulation or GABA agonism, drug-induced hyperlocomotion and drug-seeking behavior are attenuated in preclinical studies. Embera NeuroTherapeutics has found that the combination of two FDA-approved medications targeting the HPA axis and GABA, the cortisol synthesis inhibitor metyrapone and the benzodiazepine oxazepam, respectively, reduced cocaine but not food self-administration in rats. Interestingly, a similar reduction was not seen with administration of metyrapone or oxazepam alone. Embera has formulated this combination in EMB-001 and showed in a Phase 1 study that it reduced cocaine intake and craving over a six-week period, as compared to placebo. The two targets are both potentially problematic as metyrapone can induce adrenal insufficiency, and benzodiazepines, such as oxazepam, have abuse potential. However, efficacious doses of each, when combined, may be low enough to be tolerated. Embera states it is also pursuing disorders associated with methamphetamine, cannabis, tobacco, gambling, eating, and post-traumatic stress with EMB-001. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine how active the EMB-001 program is, given that the results of the cocaine-use-disorder Phase 1 trial were published in 2012 without publicly available information on follow-up trials to date. However, Embera's website indicates they received funding for a Phase II trial in 2019.

Psilocybin

Over the last decade, there has been a resurgence of interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics and psychoplastogens, such as psilocybin. The focus is on both their ability to aid psychotherapy and in their direct mechanistic actions. While no clinical studies on the effectiveness of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of StUD have been completed, psilocybin's therapeutic efficacy in major depressive disorder, as well as alcohol- and tobacco-use disorders suggests there may be potential. In further support, psilocybin suppresses methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion and the acquisition of methamphetamine-associated conditioned reward in rodent studies. Psilocybin's actions are primarily attributed to serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2AR) agonism, and activation of this receptor has been linked to cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Furthermore, relapse-like behavior in cocaine self-administration is disrupted by inhibition of 5-HT2AR during forced abstinence. A number of clinical trials with psilocybin have been initiated for StUD. For example, a Phase 1/2 trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for methamphetamine-use disorder was initiated in 2022. The Sponsor, the Portland VA Research Foundation, anticipates results in late 2024 (NCT04982796). Last year (2023), Revive Therapeutics initiated a Phase 1/2 trial to test oral psilocybin for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorder (NCT05322954). An initial readout was expected in Q3 last year but has not been released. The latest update indicates that Revive is preparing a Phase 2 completion report for FDA. A similar trial for cocaine-use disorder sponsored by University of Alabama at Birmingham is expected to be completed this year (NCT02037126). Earlier-stage efforts are also underway to modify psychedelics to remove their hallucinogenic properties while maintaining the benefits. Delix Therapeutics is one such company, and they are developing DLX-007, a compound based on ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT, for opioid use disorder.

Phosphodiesterase 10A

As the understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms supporting and driving compulsive drug use has progressed, so have the scientific tools to address specific targets. Phosphodiesterase 10A is an enzyme that hydrolyzes cAMP and cGMP to the inactive form. It is heavily expressed in medium spiny neurons of the striatum, where it can modulate dopamine transmission. Its inhibition has shown potential as a therapeutic for schizophrenia, cancer, and erectile dysfunction. In 2017, MediciNova completed a randomized Phase 2 trial for methamphetamine dependence with ibudilast (MN-166), an inhibitor of several PDEs, including PDE10 (NCT01860807). Unfortunately, the study failed to reach its primary endpoint of methamphetamine abstinence at the end of the 12-week trial (NCT01860807). An ongoing Phase 2 trial is currently exploring ibudilast's effects on neuroinflammation in methamphetamine dependence (NCT03341078).

Nonmuscle myosin II

Stimulants induce significant and lasting neuroplasticity in the brain that later supports the sustained motivation to seek drugs, even following long periods of abstinence. The molecular ATPase motor, nonmuscle myosin II (NMII), drives much of this plasticity through its effects on the synaptic cytoskeleton. Interestingly, our group found that NMII remains uniquely active in the basolateral amygdala long after methamphetamine exposure and that a single administration of an NMII inhibitor selectively excises the motivation to seek methamphetamine in preclinical models. The effect persists for at least one month post treatment in rodent studies. Myosin Therapeutics is currently developing a first-in-class NMII inhibitor, MT-110, and is expected to begin patient recruitment for a Phase 1 clinical trial in late 2024. The single-administration modality is seen as particularly promising by clinicians in light of the patient compliance challenges associated with StUD.

Monoclonal antibodies

Utilizing monoclonal antibodies as a potential therapeutic for cocaine use disorder (CUD) was first purposed in the early 90s and has been recently reviewed in detail. Currently, high-affinity, antimethamphetamine monoclonal antibodies are being developed to antagonize the drug's peripheral actions. These nonaddictive antibody-based therapies are being developed with a long half-life to remain present in the bloodstream for weeks, sequestering methamphetamine and reducing the drug's effects throughout the body, from reward to potential overdose.

The human/mouse chimeric form of the antibody (ch-mAb7F9) binds to its targets (methamphetamine, amphetamine, and MDMA) with high affinity and specificity. In rats, it reduces methamphetamine's volume of distribution and increases its elimination half-life. From a series of Phase 1 and 2 clinical studies, InterveXion Theraeputics reported that ch-mAb7F9 (also known as IXT-m200 or devestinetug) has excellent tolerability and a long half-life (17–19 days), is safe in methamphetamine-overdose patients who present to a hospital emergency department, and improves symptoms such as agitation (NCT04715230, NCT03336866). In an ongoing Phase 2 trial, its efficacy in preventing or reducing relapse is being evaluated in people seeking treatment for methamphetamine-use disorder (NCT05034874).

IXT-v100 (also known as ICKLH-SMO9) is another strategy under development for methamphetamine-use disorder by InterverXion. IXT-v100 is a conjugate vaccine in which a methamphetamine-like hapten (SMO9) is covalently linked to a protein (immunocyanin monomers from keyhole limpet hemocyanin, ICKLH). It generates a strong and long-lasting antibody response against methamphetamine both in mice and rats. In rats, IXT-v100 also increases methamphetamine serum concentrations, and decreases methamphetamine-seeking and self-administration, without altering food seeking. The increased serum concentration of methamphetamine is accompanied by an extended half-life as methamphetamine is sequestered by antimethamphetamine IgG antibodies in the blood, changing the distribution of the drug in the body. These results suggest that IXT-v100 could not only improve general health but also decrease the consumption and motivation for methamphetamine.

Conclusion

While not exhaustive, this review highlights just how troublingly thin the therapeutics pipeline is for StUD. This is particularly true when contrasted against efforts focused on opioid treatments. Our hope is that researchers in academia and industry are spurred to push more compounds with novel mechanisms of action into the pipeline. This is no simple task, particularly given the complications introduced to clinical testing by the high rate of polydrug use, as well as the rate of failure inherent to any drug development program. However, developing treatments for StUD is critically needed to realize this therapeutic goal in order to help a rapidly growing patient population and potentially to save many lives. And finally, given the complex and highly individualistic nature of all substance use disorders, the ideal approach will be a multimodal treatment plan, in which novel pharmacotherapies for StUD are paired with abstinence support mechanisms and behavioral modification therapies, such as CM and CBT. This could be further combined with recent technology-mediated advancements that utilize smartphone apps, text messaging, and telephone counseling modalities to strengthen the impact of other therapeutic approaches, such as CM and CBT.