Abstract

A tenfold increase in prison populations has occurred due to the policies and laws enacted by the War on Drugs campaign in the United States. This increase is the direct result of a rise in the incarceration of nonviolent drug offenders. Rearrest rates for nonviolent drug-related offenders sentenced to prison are 50%. For those offenders permitted to participate in a drug court program, this rate decreases by over half. In West Virginia, the battle against the opioid epidemic has caused it to become one of the fastest-growing prison populations in the nation. With a fast-emerging crisis on the rise, West Virginia state officials are seeking a solution. This Article will argue the answer lies in investing in state and federal community-based drug court programs that already exist. Not only are these programs more cost-efficient, but they are successful in preventing relapse and recidivism on a long-term scale—a result mass incarceration has been unable to achieve over the past fifty years.

I. INTRODUCTION

Nationwide, an estimated 78% of all property crimes and 77% of public order offenses relate to drug or alcohol use—coming with a $74 billion price tag per year when factoring in the cost of police, court, prison, probation, and parole services.1 To date, “1.16 million Americans are arrested annually for drug related offenses,”2 a significant contributor to ranking the United States the number one nation for prisoner rates, with 639 prisoners per 100,000 of the national population.3

In West Virginia, the rise of the opioid epidemic has driven this rate even higher, with 731 prisoners per 100,000 people in the state.4 This rate continues to increase despite “West Virginia ha[ving] one of the lowest crime rates in the country . . . rank[ing it] thirty-eight out of fifty states.”5 Thus, West Virginia currently maintains one of the “fastest increasing rates of prison growth, nearing seven percent each year . . . a faster pace than all other states in the nation.”6

In 2009, an emerging prison overcrowding crisis compelled thenGovernor Joe Manchin to initiate a commission—through a legislative mandate—to provide a comprehensive review of criminal sentencing guidelines and potential solutions.7 In its Report, the Governor’s Commission on Prison Overcrowding (“GCPO”) recommends the answer lies in “inves[ting] in all levels of community and institutionalized services.”8 A solution also endorsed by the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (“PCLEAJ”) in 1967, recognized before the wake of mass incarceration onset by the War on Drugs.9 Additionally, in its Report, the GCPO states it “believes that by significantly reducing [the] length of stay for other . . . nonviolent, property and drug crimes, an additional 200 prison beds could be made available.”10 After all, this class of offenders makes up three-quarters of all prison admissions.11

As recent as 2021, the West Virginia Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation (“WVDCR”) maintain the problem persists as West Virginia prisons have remained at or over capacity over the previous five years.12 The solution—no different than the PCLEAJ’s 1967 proposal and the GCPO’s 2009 proposal—investing in community services. Such community services state and federal drug court programs can now provide.

With the passage of legislation authorizing their establishment on the federal level in 199513 and thereafter on the state level in 2010,14 drug court programs in West Virginia have shown early success. For example, as of 2013, “[a]dult drug court programs have graduated 1,002 participants, spending $7,100 per participant, per year.”15 These individuals’ successful rehabilitation into society cost a mere one-third of the cost of incarceration for one year—roughly $26,079.16 However, for inmates over 55, that number increases to approximately $69,000 annually due to increased health-associated costs.17 Considering these rates, “if the 1,002 drug court graduates had served a year sentence in jail rather than an equal term in drug court, the cost savings would total more than $11 million.”18 With an investment of $5 million, roughly 360 additional graduates each year would yield an estimated $4 million in direct savings and $9 million in long-term savings.19

Thus, with more government-invested resources, drug court programs, on a larger scale, can provide a viable solution to prison overcrowding West Virginia officials are seeking. To skeptics, former Justice of the Superior Court of Orange County, California, James Polin Gray, asks, “[g]iven the much higher expense of incarcerating someone for a year, both in financial and human terms [] and given that rehabilitation is seven times more cost-effective in treating drug addiction and abuse, what do we have to lose?”20 With an average return of $7 in reduced health and social costs for each $1 invested in treatment, drug court programs’ cost-benefit analysis far exceeds the results produced by institutionalization. And for each criminal defendant—given the tools and resources to obtain a new life in sobriety—the benefit is priceless.21

Moreover, the need for treatment is at an all-time high in West Virginia amid the opioid epidemic, which remains rampant. As recent as 2015, the nation was shocked by headlines ranking the state as number one in overdose deaths in the country.22 For every 42 of 100,000 people in West Virginia, their battle with addiction ended as another statistic.23 Even so, another 42,000 West Virginians reported needing addiction treatment for drugs (especially opiates) but did not receive treatment in 2015.24

As outlined below, this Article will argue that community-based drug court programs offer our state the most readily workable solution to prison overcrowding. First, Part II of this Article will overview the War on Drugs and how nonviolent drug offenders have driven prison populations to unforeseen numbers. Next, Part III of this Article will explain how drug court programs are much more successful in providing cost-effective long-term results the institutionalized context has failed to achieve. Subsequently, Part IV of this Article will provide a model overview of the federal Drug Court Program for the United States District Court for the Northern District of West Virginia. Next, Part V of this Article will explain what characteristics research-based evidence identifies as indicators of success for potential candidates for drug court programs. Finally, Part VI of this Article will provide a synopsis of West Virginia state drug court programs so that judges, lawyers, families, and community members can identify resources for individuals in need of court-based treatment.

II. UNINTENTIONAL CASUALTY IN THE WAR ON DRUGS: THE RISE OF INMATE POPULATIONS

America’s “War on Drugs” has been accredited as initiating “some of the most extensive changes in criminal justice policy and the operations of the justice system in the United States since the due process revolution of the 1960s.”25 The War on Drugs marked the sudden end of “[d]ecades of stable incarceration . . . as the [United States] prison population soared from about 300,000 to 1.6 million inmates and the incarceration rate from 100 per 100,000 to over 500 per 100,000.”26 The demands of mass incarceration shifted old rust belt industries, “the economic backbone of America for decades,” into the arena of prison construction.27 On average, the United States opened three 500-bed prison facilities weekly in the country.28 Each cell costs taxpayers an estimated $100,000.29

Put differently, nonviolent drug-related offenders have been accredited as the “raw materials” for prison expansion.30 Just as the paper industry needs trees—the prison industry needs inmates; the “key difference, however, is that trees may well turn out to be a finite resource.”31 Beginning under the lead of President Richard Nixon, who first declared drug abuse “public enemy number one,”32 the goal and purpose of the War on Drugs was “to eradicate all of the social, economic[,] and health ills associated with drugs and drug abuse.”33 Taken together, Congress’s passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention Control Act of 1970, commonly known as the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”), and Nixon’s authorization of the implementation of the Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”) in 1973 to regulate and enforce the CSA, set off the beginning of mass incarceration in America.34 At this time, the prison population in the nation was relatively low, “with most states having about 130 to 260 prisoners per 100,000 people.”35 Since the 1980s, this number “has more than quadrupled.”36

Following President Ronald Reagan’s transition into office in 1981, his administration “initiated a ‘hardball’ approach to the War on Drugs movement, launching various task forces to deal with the drug problem and restoring the power of courts to prosecute criminals.”37 With the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, an additional $1.7 billion was allocated to drug enforcement, $96 million for the construction of new prisons, $200 million for drug education, and $241 million for rehabilitation programs.38 However, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act “is perhaps most notoriously known for enacting the federal minimum sentencing for crack cocaine violations, and doing so during a time when sentencing for drug offenses was becoming highly publicized.”39

Subsequently, in 1988, President George H.W. Bush signed the AntiDrug Abuse Act of 1988 into law, a piece of legislation Regan introduced shortly before the end of his second term in office.40 Six years later, in 1994, President Bill Clinton implemented the infamous federal three strikes provision, mandating a minimum sentence of twenty-five years for third felonies, meaning “many [] nonviolent drug offenders will grow old in prison.”41 By 1998, the United States incarceration rate hit a new high of 668 inmates per every 100,000 Americans, giving it “a higher incarceration [rate] than any other country except Russia, which reported a rate of 685.”42

Even more problematic, the demographics of prison populations driven by the War on Drugs are disproportionately high for racial minorities.43 As recently as 2020, the United States imprisoned Black adults at 4.9 times the rate of White adults.44 For drug offenses, black adults spend approximately 2.1 years behind bars, while white adults spend only 1.1 years.45

Similarly, prison expansion rates are inconsistent on a state-by-state basis. For instance, between 1990 and 1999, West Virginia underwent a 126% increase in the total number of inmates in state prisons, second nationally only to Texas, which had a 176% increase.46 From 1999 to 2004, the number of overdoses in West Virginia increased by 550%.47

In total, the return on the federal government’s cumulative investment of over $1 trillion over the past fifty years is nonexistent as drug use in the United States continues to climb, with 13% of all Americans twelve or older using illicit drugs in 2019, an all-time high.48 When adjusted for inflation, the federal budget’s annual appropriation of $34.6 billion for the prevention and control of drug use translates to a 1,090% increase from 1981.49

In reality–America remains “in the midst of the most devastating drug epidemic in [United States] history.”50 Amidst the crisis, special drug courts, implemented to relieve overburdened criminal courts, may constitute the most beneficial outcome of over 50 years of laws designed to prevent drug abuse by institutionalization.51 The time is now for states and the federal government to redirect funding growing prison and jail to problem-solving drug court programs. Not only are these programs more cost-efficient—but they work.

III. DRUG COURT: THE SUCCESSFUL ALTERNATIVE TO INSTITUTIONALIZATION FOR DRUG-RELATED OFFENDERS

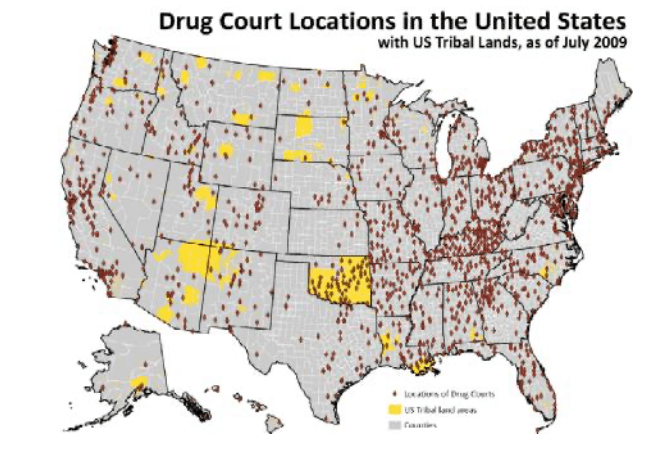

The first federal drug court program was established in Miami, Florida, in 1989 by head prosecutor Janet Reno.52 The Honorable Stanley Goldstein, “a former military policeman turned hard-nosed, tough-on crime judge,” would be the presiding judge over the first drug court.53 Judge Goldstein acknowledges that despite his harsh crime sentiments, “[w]hatever we were doing for the last 30 years, [is not] working.”54 Today, Reno and Judge Goldstein’s “legal experiment” efforts have multiplied, placing federal and state drug court programs on the map across all 50 states.55 As of 2022, more than 3,800 programs exist throughout the United States.56 By 2009, these programs have served approximately 120,000 Americans, providing them with the assistance they need “to break the cycle of addiction and recidivism.”57

In a national study, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) found that “84 percent of drug court graduates have not been re‐arrested and charged with a serious crime in the first year after graduation, and 72.5 percent have no arrests at the two-year mark.”58 Overall, the DOJ identified that “well-administered drug courts were found to reduce crime rates by as much as 35 percent, compared to traditional case dispositions.”59

Moreover, while it is hard to put a numerical value on the social productivity accomplished by drug court programs, increases in child support payments, earnings, and education are recognizable impacts.60 Additionally, the avoided harm to future victims is a nonrecoverable benefit that fosters safer communities.61 For participants, access to resources to obtain medical, dental, and vision care are all cognizable benefits provided through drug court programming. In West Virginia, the West Virginia Jobs and Hope program, established by Governor Jim Justice and the West Virginia Legislature, regularly partners with state and federal drug court programs to provide subsidized dental care.62 A new smile, for many participants, helps benchmark a new life in recovery.

In sum, drug courts provide substantial social and economic benefits on the state and community levels. Today, “treatment courts are the single most successful intervention in our nation’s history for leading people living with substance use . . . out of the criminal justice system and into lives of recovery and stability.”63

IV. A MODEL OVERVIEW OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA’S FEDERAL DRUG COURT PROGRAM

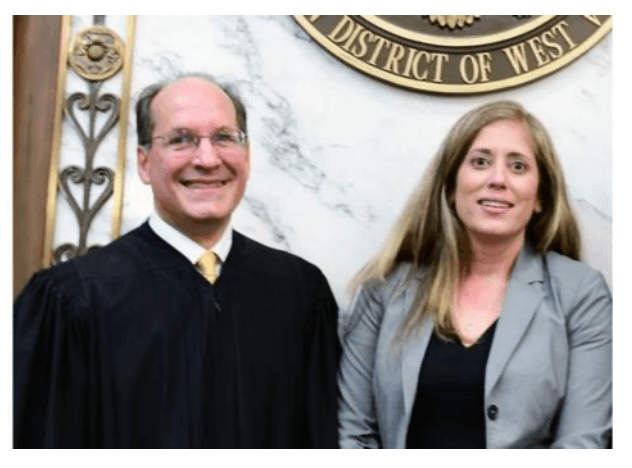

In 2014, the United States Magistrate Judge for the Northern District of West Virginia, the Honorable Michael J. Aloi, established the first federal drug court program in West Virginia.64 An alternative to prison, the 18 to 24-month treatment program requires participants to engage in “extensive supervision, frequent drug testing, individual and group counseling, relapse prevention, learning to set and achieve personal goals, demonstrating responsibility, and realizing a clean and sober lifestyle as a productive and contributing community member.”65

Generally, “[a]n applicant’s eligibility [to the program] is fact-specific, and applicants will be considered and admitted on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of the Court.”66 However, the program’s design is to serve nonviolent offenders with a history of drug or alcohol addiction.67 Therefore, individuals charged with or previously charged with felony convictions for a crime of violence, sex offense, or a severe mental condition are ineligible for consideration to the program.68

Candidates may be referred to the program by judges, defense attorneys, probation officers, Drug Court Team members, or family members.69 After an application is received, a probation officer initiates a screening process to measure a candidate’s willingness and ability to participate in the program.70 Once the probation officer completes the screening process, the Drug Court Program Team periodically discusses candidate assessments before referring them to the presiding judge for consideration.71 After reviewing referrals, if the presiding judge approves a candidate, they may be subject to a substance abuse evaluation by the program’s treatment providers.72 For accepted candidates, their defense counsel will then file a motion for transfer of supervision to the drug court program.73 The Court will then issue a continuance of further proceedings until graduation.74 For candidates who are rejected, his or her criminal case will proceed on schedule to final disposition.75

Participants enter the program voluntarily post-plea agreement, meaning participants must apply to the program and plea to a drug court-specific agreement for consideration by the Court for deferral.76 While the program is “strictly voluntary,” all “participants must agree to abide by all the rules and phases of the program, including its termination procedures, as well as any additional instructions or orders issued by the presiding judge [District Court Judge Thomas Kleeh] or by the Supervising Probation Officer [Jill C. Henline].”77 Each participant agrees to these terms and conditions through a formal written agreement, signed by themselves, their defense counsel, and Jill C. Henline to indicate their consent.78

The Drug Court Program’s treatment curriculum consists of four “Phases” that provide “distinct and achievable goals” designed to build new habits and combat criminal thinking styles crystallized during active addiction.79 Phase One through Three provides intensive treatment, whereas Phase Four, also referred to as the “aftercare” phase, provides a less rigid structure “designed to serve as a supervised transition to an independent, healthy, drug-free lifestyle.”80 During the foundational portion of Phase One, for approximately four months, participants work to “develop an understanding of addiction, patterns of use, and factors that influence use.”81 Among many things, participant expectations include: (1) attend a minimum of one weekly meeting with their probation officer; (2) attend a minimum of three self-help meetings weekly; (3) attend bimonthly Drug Court proceedings; (4) submit to home visits; (5) identify triggers and establish a relapse prevention plan; (6) identify a sober support network (i.e., personal sponsors); (7) comply with 10:00 p.m. curfew; (8) perform a minimum of eight hours of community service per week; (9) make a plan to pay off courtordered restitution, and, if possible, begin making payments; and (10) submit to random and frequent drug testing each week.82 As a benchmark, participants must “maintain sobriety for at least two consecutive months” before phasing up.83

Next, Phase Two provides participants with the tools to build a sober support network within their community by learning to understand the adverse consequences of drug use and how they take responsibility for their actions.84 During Phase Two, participants must maintain all required expectations of Phase One in addition to: (1) seeking and securing employment or enrolling to attend an educational or vocational program; (2) begin (or continue) making payments on any court-ordered restitution; and (3) maintain stable housing.85 Participants must maintain sobriety for three months to advance to Phase Three.86

In the last intensive treatment phase, Phase Three, participants must complete and submit for approval by the Court—a relapse prevention plan.87 Before participants move to Phase Four, they must achieve twelve consecutive months of sobriety.88

Finally, Phase Four provides a less demanding structure, focusing on providing participants with the independent ability to maintain their healthy, drug-free lifestyle.89 To be eligible for graduation from the program, participants must demonstrate they have maintained sobriety for eighteen consecutive months.90 Nevertheless, the Drug Court Team is mindful that “relapses are likely.”91 Thus, so long as a participant is honest about positive drug screens, the program can address such issues through sanctions and setbacks, providing candidates with multiple opportunities to succeed.92 Even so, multiple positive drug screens or non-compliant behavior may result in termination from the program.93

Since its implementation in 2014, the Northern District of West Virginia’s Drug Court Program has had 25 successful graduates who have become recovery coaches and college students and received promotions from their employers. Many graduates have also regained custody of their children. The number of successful graduates will increase to 27 by the end of 2023.

The program’s 13 active participants have accomplished 1,528 negative drug tests and 264 collective months of sobriety. One current participant made the following statement in reflection of his experience in drug court:

I am very grateful for the opportunities that have been given to me. I can’t begin to express the gratitude I have for the people that have helped me get to where I am. The first person that I’m grateful for is Judge Aloi. He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself. Instead of keeping me in jail, he gave me a chance to get treatment and completely change my life.94

For many participants, time in prison failed to provide the necessary community support and access to resources essential to combat relapse and recidivism on a long-term scale. In addressing this issue, Judge Aloi stated:

[I]f you want to measure a community in what’s powerful and good about a community, then you measure how they care for and love the most vulnerable in the community, and so here we are in the court system doing it in a real way. People see the court system as a place of accountability and consequences, and it should be . . . but we also can be a place of hope and second chances. When we do that, we do something that’s long-term.95

The twenty-five successful graduates of the Northern District’s Drug Court Program are concrete evidence of the community-based solutions available to combat the opioid epidemic and prison overcrowding dually.

V. WHICH NONVIOLENT DRUG-RELATED OFFENDERS ARE BEST SUITED FOR REFERRAL: PRELIMINARY INDICATORS OF SUCCESS

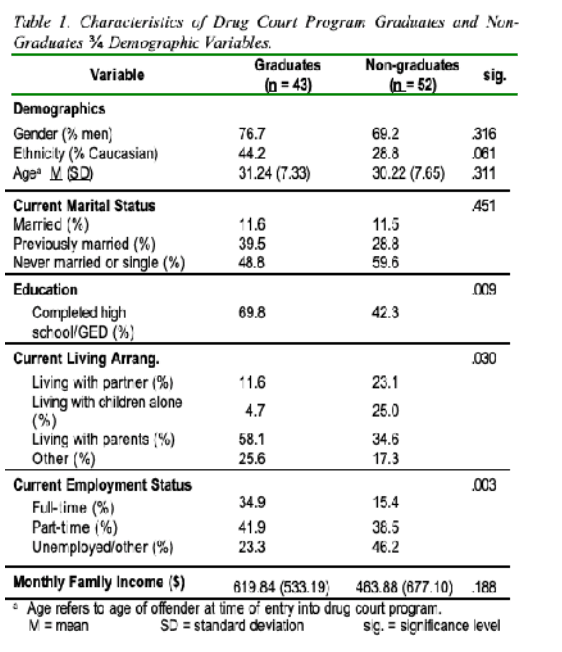

Since its establishment in 1994, the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (“NADCP”), and its divisions, have identified trends among successful drug court participants.96 While by and large, “it is not known why treatment is effective for some people and not for others,” identifiable characteristics help indicate whether an individual may be right for participation in a drug court diversion program.97 Cognizant of these findings, the Northern District of West Virginia’s Drug Court Team has begun updating its application process to reflect preferential acceptance to individuals who demonstrate readiness for participation and the characteristics associated with success. Jill C. Henline recognizes many of these trends are consistent with the directives of the Post-Conviction Risk Assessment Model (“PCRA”), a scientifically based instrument for federal probation officers to identify inmates with the most significant risk of failing supervision or committing new crimes.98 Taking PCRA risk factors and NADCP research findings into account, the following comprehensive analysis will identify characteristics of nonviolent drug offenders that may make them ideal for drug court diversion programs. As listed in the table below, age, education, social support networks, and employment are among the readily identifiable demographics which may influence a candidate’s readiness to participate in a drug court program.

99Each of these characteristics: (A) age, (B) social support networks, (C) education, and (D) employment, will be further analyzed in the subsections to follow. In addition to these enumerated categories, subsection (E) will explain why candidates who are “high risk” and “high need” are best situated for the tight supervision and demanding structure drug court programs now provide.

A. Age

First and foremost, younger age is generally associated with higher recidivism rates, regardless of the crime committed.100 The heightened risk of recidivism is due primarily to the tendency of drug abuse and addiction to manifest during teenage and early adulthood rather than later stages in life.101 Accordingly, candidates of older age (i.e., over 40) are less likely to recidivate and more likely to find success in drug court programs naturally.102 Therefore, while not dispositive, a candidate’s age should be considered a contributing factor to projected success.

B. Social Support Network

Social support networks also influence a participant’s success in a drug court program. PCRA identifies single persons are at an increased risk for reoffending.103 However, even for married persons under supervision, having a partner who similarly struggles with addiction may increase relapse or recidivism rates.104 Thus, PCRA identifies these networks as a facilitator for success during supervision for persons with stable, prosocial relationships with an intimate partner.105

Further, participants who reside with their partners and children, or alone with their children, have increased drop-out rates than those who live with parents or family members—likely due to the combination of a reduced sense of accountability in the home and the additional stressors that come with being a single parent.106 On the contrary, persons living with family members who also struggle with addiction can be an inhibitor.107 Thus, determining the positive or negative risks associated with a candidate’s social networks can be crucial in deciding whether participation in drug court is right for them.

C. Education

Lower levels of education are associated with increased crime rates and recidivism.108 However, as individuals obtain higher levels of education, these rates are generally reduced.109 For incarcerated individuals, participation in educational opportunities behind bars reduces recidivism by 48%.110 Similarly, individuals who enter a drug court program with a high school education or GED are more likely to graduate.111 Such individuals are also less likely to recidivate post-graduation than participants who have not.112 Nevertheless, education is not decisive, and many individuals can obtain their GED during their time in drug court to open up new employment opportunities.

D. Employment

Having a secure job relieves some of the stressors associated with financial stability, which often causes individuals to revert to using illicit drugs. For many, financial need may be the driving factor that initially led many drug offenders to resort to the illegal sale or trafficking of narcotics. Thus, legitimate employment is needed to replace this tendency.113 As well as exacerbating employment difficulties, having a suspended driver’s license can lead to increased relapses and recidivism.114 Drug court programs require participants to regularly meet with service providers, sponsors, and the supervising probation officer in addition to required participation in drug testing. Thus, individuals who possess a valid driver’s license or have the means to do so readily place candidates at an advantage.115 Judge Aloi identifies this as one of the most significant inhibitors to participants. However, the Drug Court Team remains committed to helping participants work to pay any outstanding court-ordered restitution to become eligible.

E. High Risk & Need

Finally, contrary to public perception, individuals considered “high risk” and “high need” for drug and alcohol use perform better in drug court programs.116 Ultimately, all drug-related adult offenders do not fit within the design of drug court programs. Instead, “[t]hey were created to fill a specific service gap for drug-dependent offenders who were not responding to existing correctional programs—the ones who were not adhering to standard probation conditions, who were being rearrested for new offenses soon after release from custody, and who were repeatedly returning to court on new charges or technical violations.”117 Accordingly, “[d]rug courts that focus their efforts on these individuals—referred to as high-risk/ high-need offenders—reduce crime approximately twice as much as those serving less serious offenders and return approximately 50 percent greater cost-benefits to their communities.”118

High-risk criminogenic risk factors include (a) age under twenty-five; (b) involvement with the criminal justice system before the age of sixteen; (c) prior violent crime involvement; (d) drug use before the age of fourteen; (e) previously failed drug treatment; (f) previously failed criminal diversion; (g) relatives in the first-degree with a drug abuse problem or criminal histories; and (g) criminal associations.119 Additionally, high needs include (1) severe indicia of drug dependence or addiction, including binge patterns, compulsions, and withdrawal symptoms; and (2) collateral needs, including chronic medical conditions, homelessness, and chronic unemployment.120

Thus, the most vulnerable members of our society fit best within the framework of drug court programs and prove that three-strike mandatory minimums are not the most cost-efficient way to deal with repeat drug-related offenders. Instead, community support is genuinely the void these individuals need to overcome their lifestyle of addiction.

All in all, these identified demographics and characteristics of nonviolent drug-related offenders can help to ensure the best-suited candidates are given priority acceptance to drug court programs. Given the currently limited ability of these programs, due to a lack of funding and resources, these statistics can guide judges, probation officers, and defense attorneys in determining which individuals are best for referrals.

On the contrary, studies have also recognized several factors which are not indicative of relapse or recidivism. First, an offender’s drug of choice fails to predict their success in a drug court program.121 Similarly, research identifies a candidate’s gender and race do not affect their likelihood of relapse or recidivism.122 Further, applicants from rural areas are less likely to relapse or recidivate than those from urban areas.123 Thus, programs should consider candidates from all racial identities, genders, and geographic locations equally suited for drug court programs.

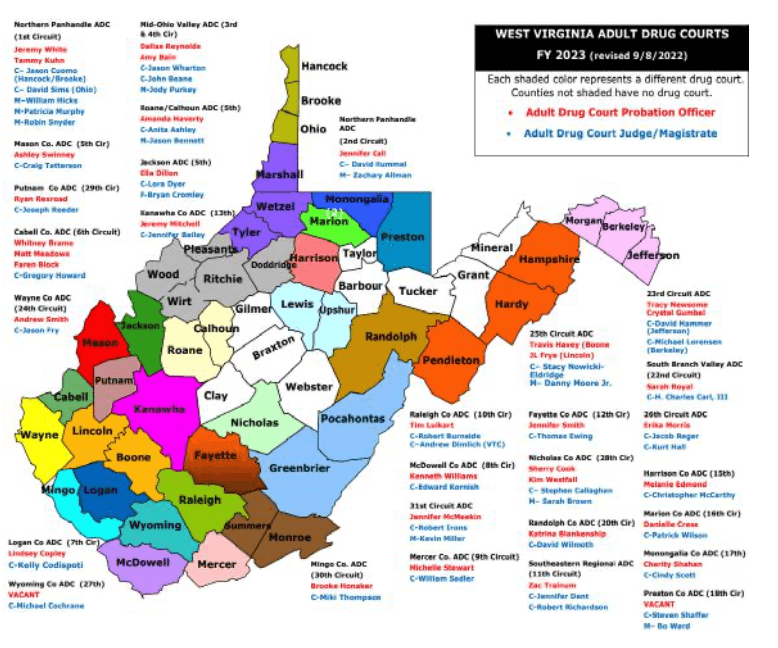

VI. AN OVERVIEW OF DRUG COURT PROGRAMS IN WEST VIRGINIA

West Virginia currently has 28 adult drug court programs, with 34 individual courts serving 46 of the 55 counties.124 Nine counties do not have operational drug court programs: Barbour, Braxton, Clay, Grant, Gilmer, Mineral, Taylor, Tucker, and Webster.125

Between 2010 and 2018, of the 2,218 individuals accepted into drug court programs statewide, 43% of participants were female, and 57% were male.126 For each participant, it cost $7,150, over half of the average annual cost for one prisoner in West Virginia regional jails ($19,425), and over a third of the cost for prisons ($26,081).127 Of the applications128 received, only 63% were accepted.129 Thus, the need for larger capacity drug court programs remains.

VII. CONCLUSION

All in all, the nearly three decades of success demonstrated by federal courts, and the two decades of state success in West Virginia, prove that drug court programs are a readily adoptable solution to the drug crisis facing our nation. The harrowing influx of prison populations and the growing opioid epidemic demand a change in our state and national drug policies.

Janet Reno, the Florida head prosecutor who started it all, was appointed to Attorney General by President Clinton in 1993, where she continued to push for reform and government subsidization of problem-solving courts.130 In a 1999 speech, as a representative of the NADCP, Janet called for expansion, stating:

[I]t is imperative, if we are to succeed, for drug courts to reach a broader population and to have an even greater impact on all aspects of our community. Despite all of the successes we have witnessed, we’re reaching only a small fraction of the approximate 800,000 arrests that are made for drug possession annually, not to mention particular drug-related offenses and probation violations. The drug court approach can provide the structure to judicially supervise all cases - adults, family and juveniles that cover substance abuse offenders living in the community. We know it works. Your challenge is to apply the model to all offenders who can benefit from it. I think we can make that happen.131

The time has come for West Virginia to accept the challenge and rethink incarceration as a solution to drug-related crimes. Drug-court programs now offer long-lasting cost-saving results for its citizens and communities. With more resources, these programs could solve the opioid crisis that hits close to home for so many.

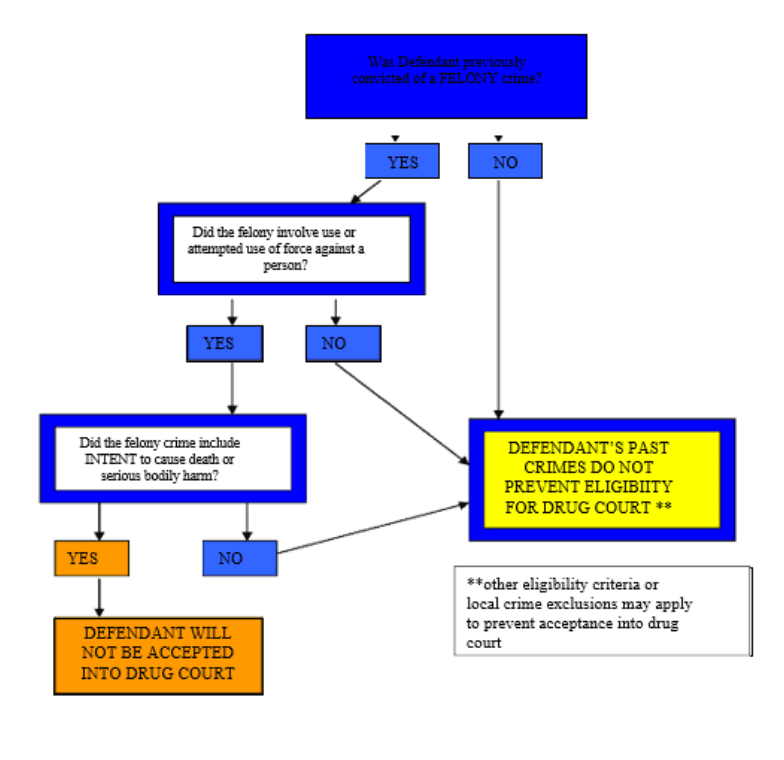

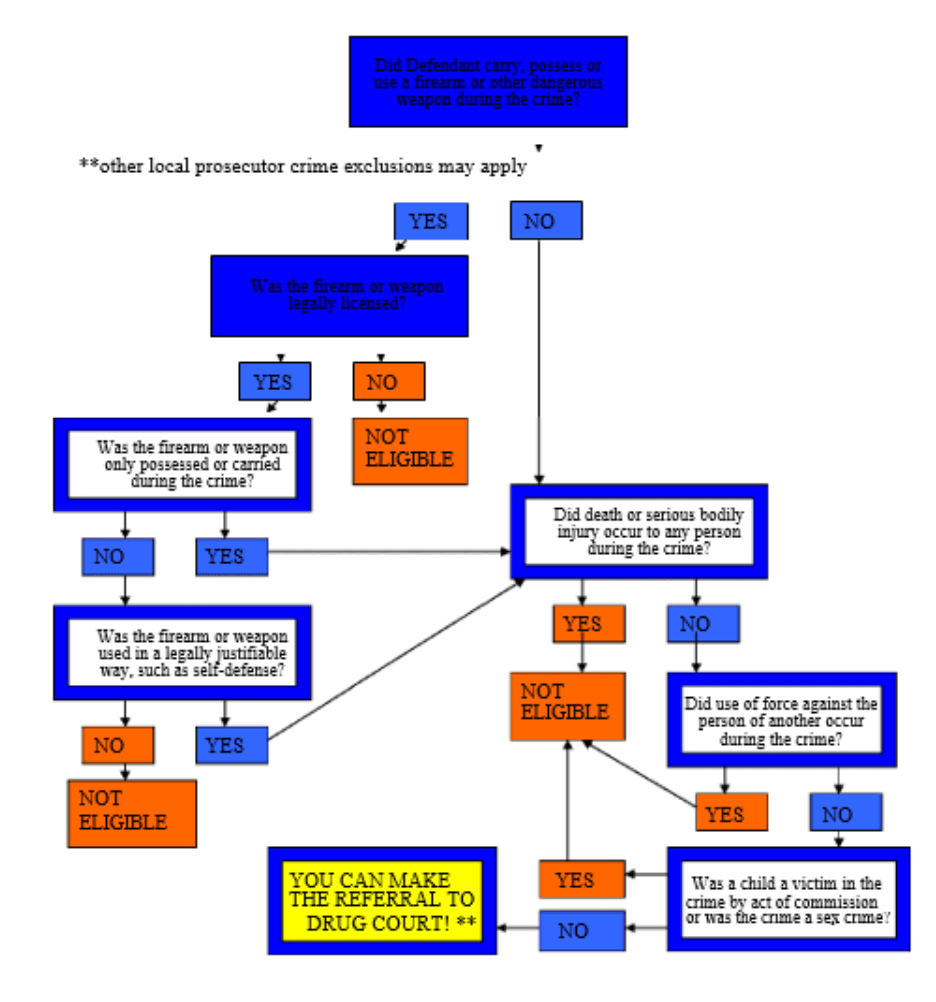

VIII. APPENDIX A

IS THIS CRIME ELIGIBLE FOR DRUG COURT?

*A Quick Reference for Current Crime Referrals to West Virginia’s Adult Drug Courts132

IX. APPENDIX B

WILL A PRIOR CRIME PREVENT ACCEPTANCE INTO DRUG COURT? *

*A Quick Reference Guide to Past Crimes and Eligibility for West Virginia’s Adult Drug Courts133