Abstract

Background: Abstinence remains a standard outcome for potential treatment interventions for Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD). However, there needs to be validation of non-abstinent outcomes. This study explores reductions in self-reported days of use as another viable outcome measure using data from three completed randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials of pharmacological interventions for CUD. Methods: The three trials tested the effect of quetiapine (QTP, n = 113); dronabinol (DRO, n = 156); and lofexidine + dronabinol (LFD, n = 122). Self-reported cannabis use was categorized into three use-groups/week: heavy (5-7 days/week), moderate (2-4 days/week) and light use (0-1 days/week). Multinomial logistic regressions analyzed the treatment by time effect on the likelihood of light and moderate use compared to heavy use in each study. Results: Across the three trials, there was no significant overall time-by-treatment interaction (QTP: p = .06; DRO: p = .15; LFD: p = .21). However, the odds of moderate compared to heavy use were significantly higher in treatment than in placebo groups starting around the midpoint of each trial. No treatment differences were found between the odds of light compared to heavy use. Conclusions: While study-end abstinence rates have been a standard treatment outcome for CUD trials, reduction from heavy to moderate use has not been standardly assessed. During the last several weeks of each trial, those on active medication were more likely to move from heavy to moderate use, which suggests that certain medications may be more impactful than previously assessed. Future studies should determine if this pattern is associated with less CUD severity and/or improved quality of life."

1. Introduction

Despite a benign public perception, Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) represents a significant public health problem. Cannabis is a widely used substance in the United States with approximately 27.7 million individuals reporting past-month use, and accounting for almost 14% of individuals receiving substance use disorder treatment, according to the 2018 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2019). While psychotherapeutic approaches have been extensively studied to treat CUD, the therapeutic benefit of these interventions do not work for many and are not easily accessible (Gates et al., 2016; Levesque and Le Foll, 2018).

Numerous medications, with varying mechanisms of action, have been tested as potential treatments for CUD. Many of the studies have been conducted in laboratory settings among non-treatment seekers (Balter et al., 2014; Brezing and Levin, 2018). Using a placebo-controlled design, medications in the laboratory are considered promising if they have been more likely to show a reduction in the subjective effects of marijuana, marijuana withdrawal symptoms or self-administration of marijuana after enforced abstinence or recent use (Balter et al., 2014). Often the positive results in the laboratory are not replicated when outpatient clinical treatment trials are conducted (Brezing and Levin, 2018; Nielsen et al., 2019). Part of this may be due to the choice in the outpatient outcome measure. As noted by Lee et al. (2019), the majority of outpatient treatment trials have focused on abstinence. While those with greater marijuana problem severity are more likely to state abstinence as a goal, a substantial minority of those entering treatment will have moderation as a preferred goal. Moreover, treatment outcome best aligns with the patient’s stated goal (Lozano et al., 2006). It may be unrealistic to expect abstinence among individuals who do not have abstinence as their initial goal of treatment or change their minds as treatment progresses (Hughes et al., 2008; Hughes et al., 2016).

One relatively large trial (n=116), conducted in adolescents with CUD, found that n-acetylcysteine was superior to placebo in promoting abstinence as the trial progressed (Gray et al., 2012). However, unlike other larger trials (n>100) that had abstinence as the primary outcome with escalating incentives targeting study adherence (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2013; Levin et al., 2016; McRae-Clark et al., 2015), for the Gray et al. study (2012) the medication was combined with a contingency management strategy that provided incentives for negative urine toxicologies for marijuana. While this approach may have enhanced the likelihood of detecting a medication effect by improving treatment adherence, when applied to adults with CUD, n-acetylcysteine did no better than placebo in producing abstinence (Gray et al., 2017).

This leads to the question of whether abstinence is a necessary goal of treatment. Conceptually, there are multiple possible targets for CUD including withdrawal, craving, attenuations of reward, reduction in use, and abstinence. The alcohol treatment literature often uses non-abstinent outcomes such as reduction in days of use and no heavy drinking use days as outcomes since they are associated with improved psychosocial functioning and reduced morbidity and mortality (Kline-Simon et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2019); however, unlike alcohol, reduction in marijuana use has not been clearly shown to produce psychosocial or medical benefits.

However, three recently published prominent studies have reported non-abstinent outcomes as their main outcome measures. A clinical trial conducted by D’Souza et al. (2019) evaluated a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor (PF-04457845), as an agent to treat cannabis withdrawal and reduce cannabis use. The authors found that compared to placebo, PF-04457845 was superior in reducing symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, lowering self-reported cannabis use at 4 weeks (measured in joints/day), and having lower urinary marijuana metabolite concentrations. Two other studies compared nabiximols (a combination medication of THC and cannabidiol) to placebo. One study found that nabiximols had a greater number of days abstinent compared to placebo but on a secondary outcome of 1 or more 4-week periods of continuous abstinence the two groups were not significantly different (Lintzeris et al., 2019). The other study found that cannabidiol, at either 400 mg or 800 mg a day, was associated with lower urinary metabolites and slightly less days of use per week (<0.5 days/week) (Freeman et al., 2020).

In a recent systematic review of measures and outcome used in treatments trials for CUD, Lee et al. (2019) note that abstinence was an outcome in 67% of trials, although 76% had reduction in frequency of use and 45% had reduction in quantity of use as a self-reported outcome. For the medication trials in which a primary outcome was reported, abstinence was the primary outcome for most studies. It may be reasonable to reconsider whether abstinence should be the primary outcome in CUD clinical trials.

Our group conducted two single site trials assessing the efficacy of dronabinol (DRO) or the combination of lofexidine and dronabinol (LFD) using a placebo-controlled, randomized design (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2016). Because DRO is a synthetic form of delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol, the naturally occurring pharmacologically active component of marijuana, it was tested on the hypothesis that, similar to buprenorphine for opioid use disorder, it would act as an “agonist” and promote abstinence. When dronabinol was not shown to impact abstinence (Levin et al. 2011), another study was conducted evaluating LFD (Levin et al., 2016). This was based on the hypothesis that lofexidine, an alpha-2- noradrenergic agonist, would mitigate cannabis withdrawal symptoms, similar to its effect on opioid withdrawal and provide complementary pharmacologic properties to dronabinol to reduce use and facilitate abstinence.

The primary outcome, abstinence, was negative for both studies. The secondary outcome measure, reduction in overall days/week of use or weekly averaged amount (as measured in dollars or grams) of use were not different for either treatment arm for the DRO trial or the LFD trial. However, neither of these trials were analyzed using the approach for our most recent randomized trial comparing quetiapine (QTP) to placebo (Mariani et al., 2020). For the recently published QTP study, similar to the earlier ones, participants were required to be daily or near daily users. QTP has a complex mechanism of action including acting as an antagonist at several serotonin, histamine, adrenergic and dopamine receptors (Nemeroff et al., 2002). Clinically, it helps with anxiety and mood stabilization and is sedating. It was hypothesized that these effects may counter some of the commonly observed cannabis withdrawal symptoms and lead to reduction in use (Mariani et al. 2014; 2020).

For the QTP study we chose reduction in days of use rather than abstinence based on an open-label pilot study results which showed that participants reduced their amount of cannabis use and number of days per week of use, with very few achieving continuous abstinence (Mariani et al., 2014). The decision to use change in days of use each week rather than a quantity of use was based on two factors; 1) the amount of use is hard to reliably assess and 2) dollars of use can vary considerably based on the potency. For all three studies, the number of days per week of use across all visits followed a bimodal or U-shaped distribution, with more participants at 0 or 7 days of use, and fewer in between. Therefore, individuals were a priori categorized into three clinically meaningful groups: light use (0–1 day a week), moderate use (2–4 days a week) and heavy use (5–7 days a week). This approach is supported by findings showing that individuals placed into these categories have significantly different levels of cannabis-related problems (Asbridge et al., 2014). Notably, compared to those receiving placebo, those receiving QTP were more likely to belong to the moderate use group compared to heavy use, with each week in the study, particularly at the halfway point of the study (week 5). Based on these findings, we were interested in conducting secondary analyses to determine if this pattern would also be observed in our two prior medication trials targeting CUD.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and study design

Details regarding recruitment, screening, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design and CONSORT Diagrams for the DRO, LFD and QTP trials have been previously reported (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2016; Mariani et al., 2020). All participants were seeking outpatient treatment for cannabis use and for both the DRO and LFD trials participants met criteria for current cannabis dependence based on the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- Axis I disorders DSM-IV (APA, 1994; First et al., 1995). Participants in the QTP trial met criteria for current cannabis dependence based on the MINI-Neuropsychiatric (Sheehan et al., 1998) for DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994).

For both the DRO and LFD trials participants had to report using ≥ 5 days/week during the prior 28 days to enrolling in the study. In the QTP trial participants had to report using an average of 5 days or more/week over the prior 28 days to enrollment in the trial. Baseline characteristics of participants are described elsewhere in detail (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2016; Mariani et al., 2020). All participants in the three trials were treated at the Substance Treatment and Research Service (STARS) of Columbia University/ New York State Psychiatric Institute. Study enrollment for the DRO trial occurred from March 2005 through November 2009; enrollment for the LFD trial occurred from December 2009 through May 2014; and enrollment for the QTP trial occurred from October 2012 through February 2017.

The DRO study was a single-site, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, clinical trial comparing placebo to dronabinol, with a maximum targeted dose of 20 mg BID. Of the 184 who were enrolled, 156 participants were randomized to receive dronabinol (n=79; 50.6%) or PBO (n=77; 49.4%) up to study week 8 (prior to dose taper and placebo lead-out) (Levin et al., 2011). The LFD study was a single-site, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, clinical trial comparing placebo to dronabinol plus lofexidine, with a maximum targeted dose of 20 mg three times a day and 0.6 mg three times a day respectively. Of the 156 participants enrolled in the double-blind study, 122 participants were randomized to receive either active medication (dronabinol and lofexidine) (n=61; 50.0%) or PBO (n=61; 50.0%) for up to study week 8 (prior to dose taper and placebo lead-out) (Levin et al., 2016). All participants in both trials received manualized motivational enhancement and weekly cognitive behavioral/relapse prevention therapy over the course of the trial.

The QTP study was a single-site, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, clinical trial comparing placebo to quetiapine (up to a maximum dose of 300 mg/daily). Of the 130 participants enrolled in the double-blind study, 130 participants were randomized to receive either active medication (quetiapine) (n=66; 50.7%) or PBO (n=64; 49.2%) for up to study week 12 (prior to dose taper) (Mariani et al., 2020). The psychosocial intervention utilized for the QTP trial was a manual-guided supportive behavioral treatment session (Pettinati et al., 2005) based on Medical Management used for Project COMBINE (Anton et al., 2006) and modified for marijuana dependence. Sessions with the research psychiatrist were weekly and meant to promote compliance with study medication and abstinence from marijuana.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cannabis Use

The timeline follow-back (TLFB) assessment (Litten and Allen, 1992) modified for cannabis (Mariani et al., 2011) was used to assess participants’ cannabis use at twice weekly visits. Details of this procedure can be found in prior publications by our group (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2016; Mariani et al., 2011, Mariani et al., 2020). A strong association had previously been found between TLFB and urine drug screens in the placebo arm of the DRO study (Levin et al., 2011) thus supporting the use of the TLFB as a reliable method to measure cannabis use.

2.2.2. Quality of Life

For the LFD study, the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form (QLES-Q-SF) was assessed at baseline and end of study (Endicott et al., 1993).

2.3. Statistical analysis

For all three studies, the number of days per week of use across all available time points, followed a bimodal or U-shaped distribution, with more participants at 0 or 7 days of use, and fewer in between. Therefore, the outcome of cannabis use days per week was a priori categorized into 3 clinically meaningful groups: heavy use (defined as 5–7 use days/week), moderate use (defined as 2–4 use days/week) and light use (defined as 0–1 use day/week). For subjects missing some days of TLFB data, the following rules were used to create the categorical cannabis use outcome: 1) for subjects with less than 3 self-reported days in a week, the corresponding week was denoted as missing; 2) for subjects with 3–5 self-reported days in a week, the missing data were imputed using the percentage of self-reported abstinent days per that week; and 3) for subjects with 6 self-reported days in a week the outcome category was determined when possible (e.g., if all 6 self-reported days were abstinent, the week was categorized as light use), otherwise the missing days were imputed as in step 2. For participants who dropped out of the study, the weeks after their last week in the study were considered to be missing.

The statistical models used for all three studies were multinomial logistic regression to accommodate the 3-category outcome. Ordinal logistic regression was considered but not used because the proportional odds assumption was violated. The effect of treatment over time was modeled using a time*treatment interaction term, where time was assessed weekly and analyzed as a continuous variable, while adjusting for age, sex, and baseline marijuana use (measured in dollars spent). The model for the QTP study also included baseline presence of co-occurring mood/anxiety disorders as a covariate. This multinomial logistic regression model generates multiple odds ratios (OR) for each binary predictor that compare the odds of achieving each category of the outcome with the reference group (heavy use). Therefore, the 3-category outcome corresponds to two ORs for each binary predictor. For example, the effect of binary treatment on the 3-category outcome in a certain week is expressed as 1) the odds of light use compared to heavy use among those who were in treatment group compared to PBO, denoted as “ORL-H”; and 2) the odds of moderate use compared to heavy use among those who were in treatment group compared to PBO, denoted as “ORM-H”. Each OR was tested using a Wald Х2 test. These odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed for each week of the study.

To assess the effect of the covariates, the same analyses described above were also repeated in two ways: (1) without any covariates and (2) with only the covariates collected across all three studies, i.e., the covariate of co-occurring mood/anxiety was excluded from the QTP analysis. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was also performed to assess the effect of dropouts, where the weeks after dropout was considered as belonging to the heavy use group.

In the LFD study (the only study with administered quality of life scale), the association between use categories and quality of life (measured by Q-LES-Q) was explored. The proportion of heavy use weeks over the course of the LFD study were calculated for each participant and correlated using a simple linear regression with Q-LES-Q score measured for each participant at the end of the study.

All models were analyzed in SAS® 9.4 using PROC LOGISTIC and all graphs were produced using R version 3.6.3. All hypothesis tests were two-sided with level of significance 5%.

3. Results

3.1. Summary results

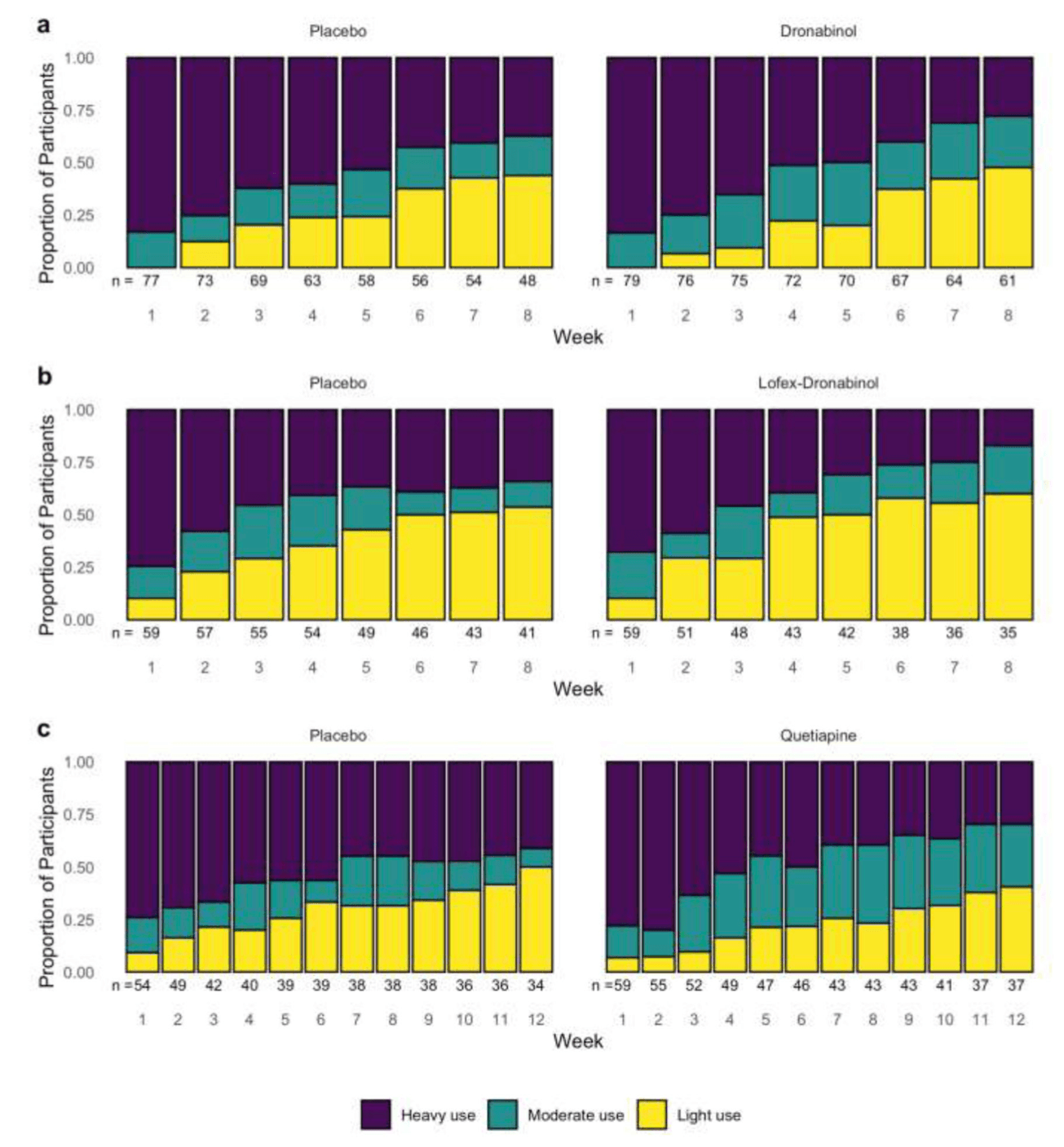

The observed proportions of participants in heavy, moderate, and light use categories by week and treatment group are shown in Figure 1 with the lightest color denoting light use and the darkest color denoting heavy use.

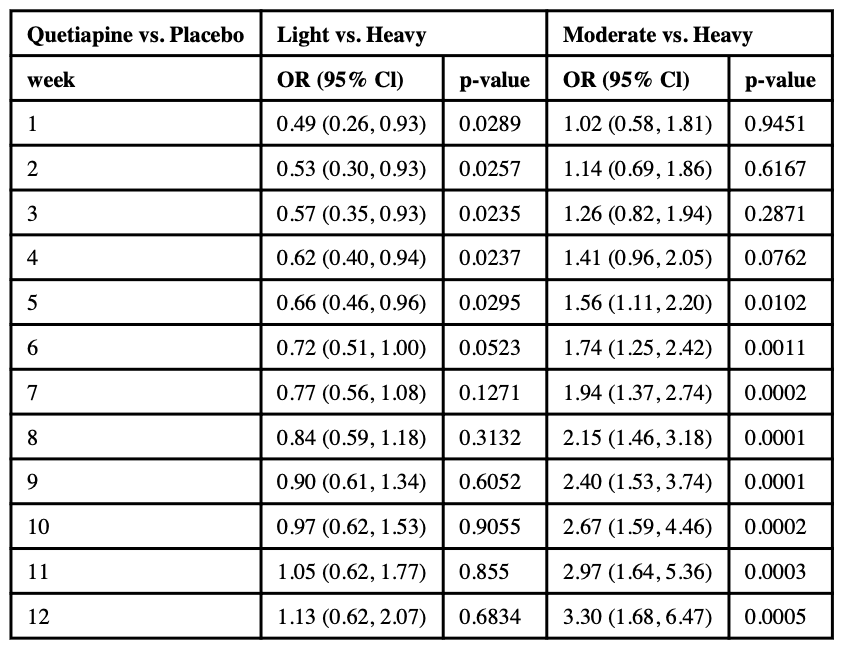

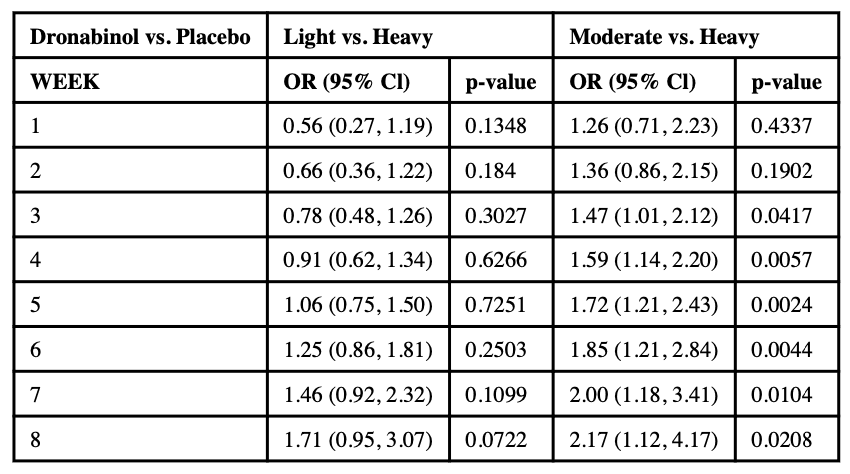

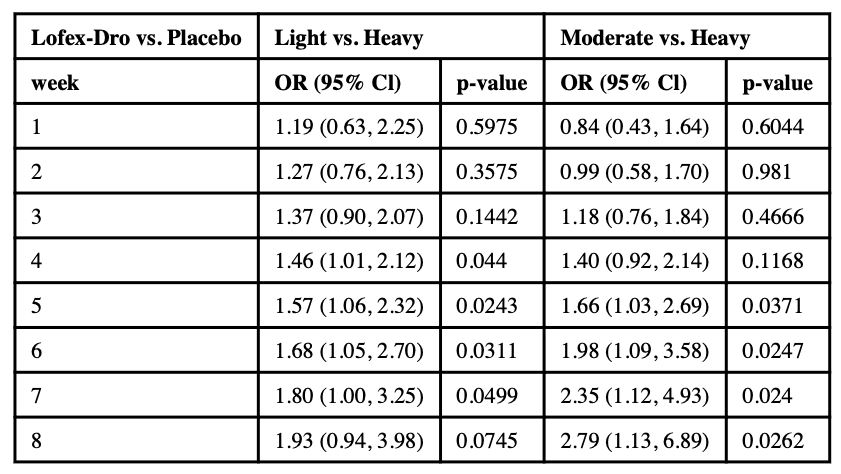

Across the three trials, there was no significant overall time-by-treatment interaction (QTP: p = .06; DRO: p = .15; LFD: p = .21), suggesting no significant differences in the longitudinal pattern of use over time between treatment groups, while adjusted by other covariates. However, all three studies showed similar patterns of increasing odds of moderate compared to heavy use among the treatment group compared to the placebo group. There were no repeated patterns of association between treatments and light compared to heavy use (see Table 1a, 1b, and 1c for details).

3.1.1. Moderate use compared to heavy use

In all three trials, similar patterns of association between moderate compared to heavy use were observed (see Figure 1). In the treatment arm, the odds of moderate use compared to heavy use were significantly higher than those in placebo, starting from around the midpoint of each trial.

Specifically, in the 12-week long QTP study, during weeks 1–4 the effect of quetiapine on moderate compared to heavy use was not significantly different from the effect of PBO. However, starting from week 5, significant differences emerge and the quetiapine group becomes significantly associated with higher odds of moderate use (Mariani et al. 2020). At week 5, the odds of moderate use compared to heavy use for the quetiapine group were 1.56 times the odds of moderate use compared to heavy use in the PBO group (ORM-H = 1.56; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.20; p = .0102, see Table 1a). At week 12, the ORM-Hincreased to 3.30 (95% CI: 1.68, 6.47; p = .0005).

In the 8-week long DRO study, during weeks 1–2 the effect of dronabinol on moderate compared to heavy use was not significantly different from the effect of PBO. However, starting from week 3, the dronabinol group is significantly associated with higher odds of moderate use compared to PBO (see Table 1b). At week 3, the ORM-H was 1.47 (95% CI: 1.01, 2.12; p = .042); at the end of the study, week 8, the ORM-H increased to 2.17 (95% CI: 1.12, 4.17; p = .021).

In the 8-week long LFD study, during weeks 1–4, the effect of LFD on moderate compared to heavy use was not significantly different from the effect of PBO. But during weeks 5–8, the lofexidine and dronabinol group was significantly associated with higher odds of moderate use compared to PBO (see Table 1c). At week 5, the ORM-H was 1.66 (95% CI: 1.03, 2.69; p = .0371); at week 8 the ORM-H increased to 2.79 (95% CI: 1.13, 6.89; p = .0262).

3.1.2. Light use compared to heavy use

There was no repeated pattern of association between treatments in light use compared to heavy use across these three analyses (see Tables 1a, 1b, 1c). In the QTP study, the odds of light compared to heavy use was significantly lower for those in the quetiapine group during weeks 1–5 only. Whereas in the LFD study, the odds of light compared to heavy use was significantly higher in the LFD group later in the study, during weeks 4–7. No significant treatment effect on light compared to heavy use was seen in the DRO study.

3.1.3. Sensitivity analyses of dropouts and covariates

Removing all covariates from the analyses or keeping only those covariates that were collected in all three studies did not meaningfully change the original results.

The results of sensitivity analysis in which dropouts were treated as heavy users were also not meaningfully different from the original results presented above. All patterns of use described above were similar.

3.2. Proportion of use categories and quality of life

For the LFD study, the only study where the QLESQ-SF assessment was conducted, there was an association between proportion of heavy use weeks and Q-LES-Q score at week 12 (p = .0079): for a decrease of 10% in the proportion of heavy use weeks, the Q-LES-Q score increased, on average, by 0.87 points.

4. Discussion

Earlier analyses of two published trials did not find that abstinence or overall reduction in days of use were greater among those on active treatment compared to the placebo arm (Levin et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2016). However, conducting secondary analyses using an approach conducted with a recently completed trial (comparing quetiapine to placebo, Mariani et al., 2020), found a similar pattern of results. Specifically, for all three studies, starting at the midpoint of each trial the odds of moderate compared to heavy use were significantly higher in the treatment arm. This pattern was not consistently observed in the odds of light compared to heavy use across treatment groups.

The critical question is why this observation occurred. While most patients will report that abstinence is their goal when they enter treatment (Lozano et al. 2006), this often changes over time (Hughes et al. 2008; 2016). While we did not formally evaluate for motivation to become abstinent for two of the trials (Levin et al. 2011; 2016), our clinical observations were that the goal of abstinence is not tightly held, particularly if a participant is satisfied with a lower level of use. For the QTP trial, we began to routinely evaluate patients’ goals throughout treatment. In the QTP study, when asked to rate what would be considered “treatment success” on a scale of 1–10, with 1 being no reduction and 10 being complete abstinence, the majority (69%, 90/130) of the participants considered some reduction (rating between 3–9) to be a success, compared to only a third of participants rating complete abstinence as treatment success.

However, regardless of motivation or baseline treatment goals, unless there is a more powerful agonist, a negative allosteric modulator of the CB1, or an antagonist that is long-lasting and safe, it may be difficult for individuals to achieve full abstinence. Further, light use (which allows 1 day/week) may also substantially be more difficult to achieve than moderate (2–4 days/week) use, unless we develop more powerful (and safe) pharmacologic interventions.

Notably, in two of the trials we looked at reduction in use based on reduction in overall days/week of use and weekly averaged amount (as measured in dollars or grams) and found no significant reduction in overall use; whereas when we categorized patients’ use patterns into light/moderate/heavy use groups we found suggestions of group differences. There are several possible explanations regarding this potential discrepancy. First, it may be harder for participants to reliably report amount of use compared to identifying each day as a nonuse/use day. Second, participants in the placebo arm might compensate for less amount of use by converting to greater potency of marijuana use. Finally, because the distribution of use days across all three studies was bimodal, with more subjects at the extremes, i.e., 0 use days or 7 use days in any given week, using averages may not be meaningful, rather the bimodality suggests the presence of different groups of individuals and categorization may allow for a better understanding of changes in cannabis use.

What remains an important clinical question is whether the change from a heavy to moderate use pattern is clinically meaningful and a reasonable outcome. As noted by two recent reviews, there are no clear-cut valid and reliable instruments to determine clinical outcomes for CUD (Lee et al., 2019; Loflin et al., 2020). To date, the most common measures used to assess outcome are self-reported use, often determined by timeline follow-back alone or in conjunction with urine toxicology data. However, even with these commonly used measures, the way they are utilized is quite variable. Unlike the CUD treatment literature, the alcohol and tobacco literature have established greater consensus. Typically, prolonged abstinence is the preferred outcome since there is no safe level of tobacco smoking (Hughes et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2019). With regards to alcohol consumption, Lee et al. (2019) note that several studies have found that there are positive short- and long- term effects on psychosocial functioning with the eradication of heavy drinking days (Kline-Simon et al., 2013; Kline-Simon et al., 2017; Witkiewitz et al., 2017) that provide support for mild or non-risky use as an alcohol treatment outcome.

While chronic heavy alcohol use can cause various medical comorbidities, this is less clear for chronic cannabis use. There are data supporting that chronic cannabis use produces psychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairments (Andrade et al., 2016). Yet, it remains an empirical question whether reducing cannabis use would improve psychosocial functioning and psychiatric symptoms among those with such symptoms (Loflin et al., 2020). Perhaps for this reason, supplementing change in cannabis use with reduction in DSM-5 CUD symptoms might make sense (Lee et al., 2019). The limitation of this approach is that some individuals entering treatment meet criteria for mild to moderate CUD with only 2–5 symptoms, thus generating a potential floor effect when trying to detect efficacy (Hasin et al. 2016); although the majority of individuals entering CUD treatment have severe symptoms (>6). With greater acceptance of cannabis as a medicinal agent and more widespread legalization for recreational use, patients with regular cannabis use, even those entering treatment, may be less likely to endorse 6+ symptoms consistent with severe CUD. Also, using DSM-5 CUD symptoms as an outcome measure requires an awareness of how the treatment has changed the patient’s loss of control, harmful impact on social and occupational functioning, and physical dependence. Recent survey data suggest that Americans view cannabis as less harmful than a decade ago (SAMHSA, NSDUH, 2019). This may have the unexpected effect of having patients less likely to endorse DSM5 CUD symptoms, even among those entering treatment. Given these issues, it makes practical sense to use a measure of frequency of cannabis use as a treatment outcome. Reduced frequency of use/week, if it is associated with other psychosocial improvements, might be a reasonable goal.

For the QTP trial (Mariani et al., 2020), the rationale was based on our clinical experience that daily or near daily users would have greater difficulties than moderate or infrequent users. Notably, this approach was examined by Asbridge et al. (2014) and they found that near daily/daily users were found to have greater cannabis-related problems and total score on the ASSIST (the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test WHO; Asbridge et al., 2014) than less frequent users (<5 days/week). Similarly, categorizing individuals into those who used greater amounts per day (2 or more joints on days of use) was associated with having greater cannabis problems compared to those who used fewer joints (1 or less joints on days of use); however, the rationale behind the selection of these criteria for grouping was not given.

Findings from a secondary analysis of our LFD clinical trial (Brezing et al., 2018) suggest reduction in cannabis use is associated with improved quality of life. For this study we looked at the LFD trial again and found that reduction in proportion of heavy use weeks was also associated with improved quality of life, however, we cannot say if cannabis related problems/DSM symptomatology were related to either of these changes in use patterns or improved quality of life. While we cannot conclude from this secondary analysis what the best primary outcome for a cannabis treatment trial should be, we would contend that reduction in use might be considered for future trials, with improvement in quality of life/improved functioning and less cannabis-related problems as secondary outcomes. However, this does not address how reduction in use would be defined. This analysis suggests one way to measure quality of life, but without more data it is hard to conclude that it is superior to another approach. It is notable that the medications that looked promising in the human laboratory, were not so in the outpatient clinical treatment trials when abstinence was used as an outcome measure. Yet, the laboratory findings translated to positive results in the outpatient setting when categorical reduction in frequency of use was applied. It may be that for early phase II clinical treatment trials, abstinence may be too high a hurdle, and reduction in use is a more appropriate primary outcome measure.

The weekly contrasts reported in this paper were pre-specified a priori, regardless of the overall time by treatment interaction effect. There were group differences in the odds of going from heavy use to light use from weeks 1–5 in the QTP trial and weeks 4–7 of the LFD trial. However, these differences were not maintained as the trials progressed. While this early, substantial improvement is noteworthy, without extending the study length it is hard to determine whether this early effect is spurious or predictive of a future return to this robust reduction in use for those maintained on the QTP or LFD. Similarly, our positive results in the odds of going from heavy use to moderate use at the end of the three trials might be spurious, despite similar findings for all three trials.

Additionally, the sensitivity analyses treating dropouts as heavy users showed no meaningful differences from the original results presented above, suggesting that dropouts did not bias the main findings. Other sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the effect of covariates in the analyses. Removing all covariates from the analyses or keeping only covariates that were in all three studies did not affect the original results.

A limitation of this study is that all of the treatment conditions relied on self-report. While self-report is a standard measure used to evaluate reduction in use, there may be differential reporting of cannabis use based on treatment arm when there are differences in side effects. Mitigating this are our prior findings in which amount of use and overall days of use did not differ across treatment arms (Levin et al. 2011; 2016).

Another clear limitation of this paper is that it is a secondary analysis. However, we would contend that this secondary analysis provides support along with prior reviews (Lee et al., 2019; Loflin et al., 2020) that further research into alternative outcome measures is reasonable for cannabis treatment trials.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this secondary analysis explores an alternate way of examining outcomes in the treatment of CUD. In the current environment, abstinence as an outcome in the treatment of CUD is not a consistent goal of patients nor is it necessarily the only outcome associated with clinical or functional improvement. Medication trials that have previously been deemed “negative” as they relate to abstinence may warrant further analysis regarding their effectiveness in reducing cannabis use. Future research is needed to determine the clinical relevance of the outcome used for this paper as well as other reduction in use outcomes and their clinical and functional correlates.