Abstract

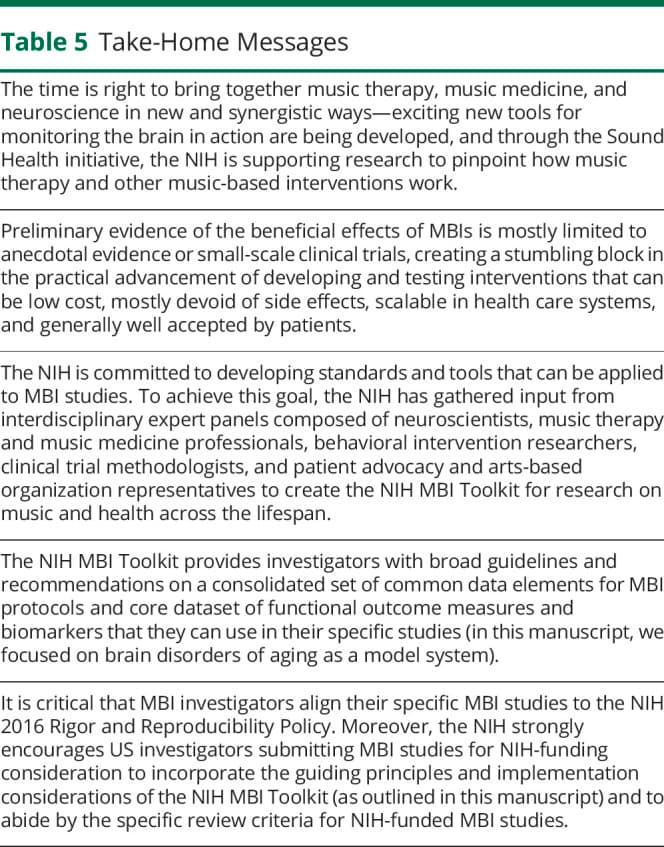

Music-based interventions (MBIs) show promise for managing symptoms of various brain disorders. To fully realize the potential of MBIs and dispel the outdated misconception that MBIs are rooted in soft science, the NIH is promoting rigorously designed, well-powered MBI clinical trials. The pressing need of guidelines for scientifically rigorous studies with enhanced data collection brought together the Renée Fleming Foundation, the Foundation for the NIH, the Trans-NIH Music and Health Working Group, and an interdisciplinary scientific expert panel to create the NIH MBI Toolkit for research on music and health across the lifespan. The Toolkit defines the building blocks of MBIs, including a consolidated set of common data elements for MBI protocols, and core datasets of outcome measures and biomarkers for brain disorders of aging that researchers may select for their studies. Utilization of the guiding principles in this Toolkit will be strongly recommended for NIH-funded studies of MBIs.

In the past decade, the amount of research into the effects of the arts on health and well-being has increased. Nonpharmacologic approaches, such as music, continue to be explored for the treatment and symptom management of brain disorders of aging, including stroke, Parkinson disease (PD), Alzheimer disease (AD), and AD-related dementias (ADRDs). There is evidence to support that music engages many different areas of the brain and may aid to strengthen brain networks and pathways involved in sensory and motor processes, emotion, affect, and memory.e1 Given that many of these domains can be affected by brain disorders of aging, music may therefore represent a cheaper, less invasive, and more accessible therapeutic avenue than traditional pharmacologic approaches.

Significant strides have been made over the past decade to further the understanding, development, and effectiveness of MBIs for various disorders. For example, rhythmic auditory stimulation (RAS), a neurologic music therapy that involves the presentation of auditory rhythmic cues, has shown great promise for the treatment of gait disorders in individuals living with PD. RAS may reduce the number of freezing episodes and number of falls in these patients. In addition, studies indicate that RAS may also provide some benefits to individuals with other neurologic conditions where gait and postural stability are affected, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, and AD. Moreover, singing can improve respiratory control and strengthening of muscles associated with swallowing and gait. Neurologic music therapy and melodic intonation therapy are used successfully for the rehabilitation of patients with nonfluent aphasia by stimulating their cognitive, emotional, and sensorimotor functions and by increasing their expressive language scores (e.g., repetition, sentence completion, and naming nouns).e2 Other studies have explored whether MBIs could improve cognitive function in healthy aging and AD/ADRD, as well as address the behavioral and psychological symptoms of AD (e.g., aggression, anxiety, irritability, and depression).

Although MBIs have shown promise for symptom management in brain disorders of aging, large-scale, rigorous, well-designed, and well-powered studies are needed to fully understand how music affects the brain and its therapeutic potential for these conditions. In the past 5 years, 2 Cochrane systematic reviews have concluded that MBIs have demonstrated benefits for people living with dementia and for people with acquired brain injury; however, these reviews have also highlighted the need for high-quality randomized trials before recommendations can be made for clinical practice. A more recent systematic review of MBIs for community-dwelling people living with dementia noted that inconsistency in study designs, procedures, and measures prevented specific conclusions to be drawn about potential therapeutic benefit.

A major limitation to widespread application of MBIs has been the scarcity of data from rigorous, well-powered studies. Reports of the beneficial effects of MBIs have emerged either from anecdotal evidence or from small-scale clinical trials.21 To further illustrate this point, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) conducted a literature review in 2017 to assess the state of the science regarding nonpharmacologic approaches, including music, that might benefit the quality of life for people living with dementia. Their 2020 report concluded from the 35 studies examined that evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions about the benefits of music therapy for agitation, anxiety, depression, mood, and quality of life for people living with dementia. Moreover, many of these studies had not been designed within a scientific and theoretical framework, and their results remain preliminary.

Another challenge for the broad implementation of MBIs is the lack of consistent descriptive terminology. MBIs are divided into 2 major categories: music therapy and music medicine. Music therapy is an established health profession in which music is used within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals and includes the triad of music, clients, and qualified credentialed music therapists. By contrast, music medicine is defined as having patients listen to prerecorded or live music, which is often managed by a medical professional other than a music therapist, such that the music plays the role of a medicine. Notably, unlike music therapy, music medicine does not require a therapeutic relationship with the patient. A clear distinction between these 2 types of MBIs is important for assessing treatment response and functional outcomes.

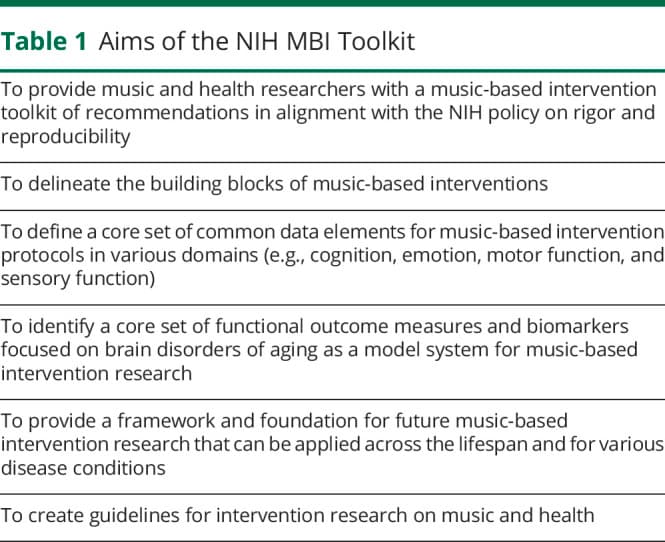

Harnessing the therapeutic potential of music is of wide interest across the NIH (21 of NIH's 27 institutes and centers have representatives to the Trans-NIH Music and Health Working Group (WG), part of the Sound Health Initiative). For MBIs to fulfill their potential, they must become more rigorous and replicable and align with the NIH Rigor and Reproducibility Policy, which will require the development of standards and tools that can be applied to interventional studies. The NIH, in partnership with the Renée Fleming Foundation and the Foundation for the NIH (FNIH), convened 3 workshops in 2021 to gather diverse and unbiased perspectives from 5 different communities representing content experts and a broad range of stakeholders (see eAppendix 1, links.lww.com/WNL/C605, for specific information on panel composition and discussion topics for each workshop). A direct outcome of these workshops is the development of the NIH MBI Toolkit: a set of guidelines and recommendations on what components need to be included in an MBI study to enhance data collection; allow for rigor, replicability, cross-study comparison, and interpretation; and advance the biomedical research enterprise (Table 1). Other health research fields (e.g., physical therapy and traumatic brain injury) have benefited from such development of standards for interventional studies.

Development of the NIH MBI Toolkit: Methodology and Approach

In preparation for the NIH-FNIH workshop series, a planning committee consisting of 12 NIH staff—Program Directors experienced in scientific program development and a subset of the larger Trans-NIH Music and Health WG—was established. Through an iterative and democratic process, and with input from the NIH Director and the Trans-NIH Music and Health WG, the planning committee members met biweekly to reach consensus on the workshop format, the selection of the members for the external expert panel, and the development of the workshop agenda.

To fully assess the state of the music and health research field, we conducted a broad and comprehensive literature and database reviews of randomized controlled trial MBI studies through PubMed and other appropriate sources (Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO, ClinicalTrials.gov, and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform). We augmented the results of our searches by including publications cited by workshop content experts and other NIH investigators in the relevant fields of neuroscience, music therapy and music medicine, behavioral intervention development, clinical trial methodology, and patient arts and advocacy.

To meet our goals of providing the research community with guidelines and recommendations on MBI development, it was critical to identify panelists with expertise in areas of direct relevance and to also bring together a truly interdisciplinary panel. For each workshop, the panel included 5 or 6 experts representing the following disciplines: neuroscience, music therapy and music medicine, behavioral intervention development, clinical trial methodology, and patient and arts advocacy. These experts were identified and selected based on their published body of work, participation at other scientific meetings, and recommendations from NIH staff and external stakeholders. The NIH planning committee was especially mindful to have an expert panel that included both scientists actively working in the field of music and health and experts in a relevant discipline but not directly involved in MBI research, thus bringing fresh and unbiased perspectives to the panel.

Before each workshop, panelists worked closely with the NIH planning committee and engaged in 2 or 3 premeetings to allow for in-depth discussions of relevant questions that were provided to them in advance. Each workshop was organized around a specific theme, framed by a keynote address, and followed by a moderated discussion led by Alan Weil, Editor-in-Chief of the health policy journal, Health Affairs. This approach was adopted to promote rich discussions, diversity of opinions from the interdisciplinary panelists, and comments from a general audience composed of basic and clinical scientists, music professionals, staff from the NIH and other federal agencies, and the public.

A unique feature of this process was the presentation of demonstration projects by 2 interdisciplinary subgroups drawn from the pool of panelists. These subgroups were tasked with developing an MBI for a particular disease or condition, applying the guiding principles that were developed throughout the 3-workshop series (see eAppendix 1 for descriptions of 2 prototype MBI studies, links.lww.com/WNL/C605). To further inform the development of the Toolkit, additional feedback and input were also gathered from the external community through a formal request for information (eAppendix 1).

Notably, the overall goal of developing the NIH MBI Toolkit is to provide standards and tools to investigators seeking NIH funding for their MBI studies, and as such, many of the selected panelists were based in the United States. The lack of representation from a cadre of international researchers engaged in music and health research may represent a potential limitation of the development process.

Essential Components of the NIH MBI Toolkit

The NIH MBI Toolkit was conceptualized to promote incorporation in MBI studies of the following elements: (1) a conceptual model or framework to guide the design of the intervention, (2) a clear research question and the provision of supporting data to test the posited hypothesis, (3) a core set of common data elements or building blocks that must be included in every MBI, (4) a comprehensive description of the intervention, (5) a detailed protocol for delivering the intervention, (6) the population to be studied, and (7) control groups or comparators.

Conceptual Models or Frameworks for MBIs

A first step in testing an MBI is developing a conceptual framework for the proposed intervention, that is, a representation of an expected relationship(s) between or among variables (i.e., the hypothesis). As in the evidence-based medicine PICOS model (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design),e4 the choice of a framework depends on the targeted population, specific intervention, comparison group, outcome measures, and research question, as well as the research stage and study design (e.g., static, mixed methods, or adaptive). Below are 4 examples of models or frameworks (behavioral/experimental medicine, music therapy, neural, and resilience/social science) that can be used in MBI research.

Experimental Medicine Framework

The NIH Science of Behavior Change (SOBC) program illustrates the experimental medicine approach to identifying and testing hypothesized mechanisms of action of therapies at each stage of intervention development, with the overall goal of improving the understanding of mechanisms underlying human behavior change. In SOBC, the focus is on defining the processes or mechanisms that are driving the behavior change or effect of an intervention, verifying the intervention target mechanism, and identifying outcome measures of target engagement. For example, in an MBI, the SOBC theoretical model would highlight the components of music that are likely to influence the potential processes or mechanisms (e.g., cognitive, emotional, or physiologic) that, in the context of a specific study, result in changes in the outcome of interest (e.g., cognitive, emotional, or functional outcomes).

Music Therapy Framework

Many factors influence the guiding framework for music therapists, including the clinical setting, client population, client age, diagnosis, and theoretical orientations of the therapist. Music therapists use a combination of various types of frameworks to address the client's needs, including psychodynamic, humanistic, behavioral, and music-centered approaches.e5,e6 For example, therapists may use a humanistic approach to facilitate respect, trust, and engagement with their clients and further incorporate a behavioral approach that uses music as a cue to redirect the focus of attention to obtain a desired response. An important consideration for determining which approaches are most appropriate is ensuring that all clients' needs will be addressed by the chosen combination.

Neuromechanistic Framework

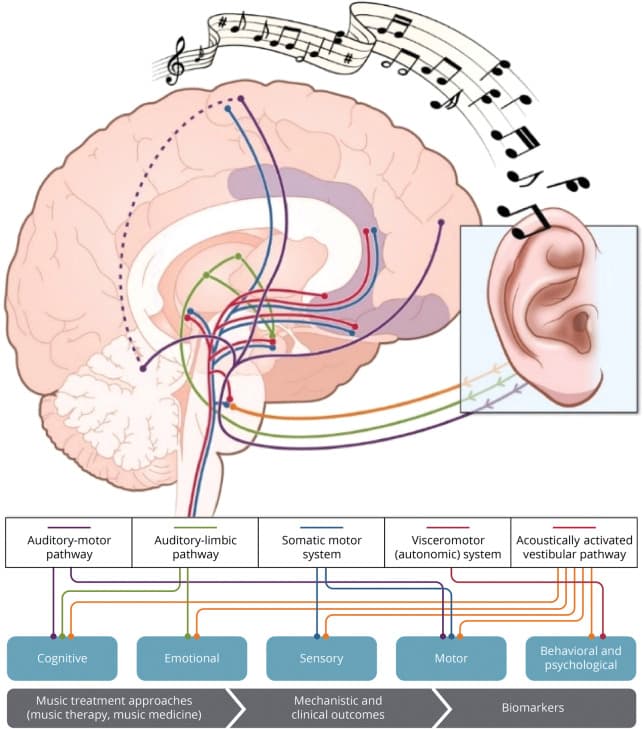

The neuromechanistic framework requires that interventional studies provide a mechanistic conceptual grounding that builds connections between clinical and basic research. Starting from the evidence that music engages many neural systems, including the perception, sensory-motor, memory, attention, and emotion/reward systems (Figure 1), MBIs for a given disorder should consider the alignment of the neural subsystems involved in both the disorder and the intervention. For example, music's ability to recruit the reward system could be exploited for conditions with motivational problems or anhedonia.

Figure 1. Pathways Underlying Neural and Physiologic Responses to Music.

Adapted with permission from Koelsch S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014; 15:170-180. doi.org/10.1038/nrn3666

Resilience Framework

The resilience framework uses a contextual support model of music therapy that is based on a motivational theory of coping. The framework argues that therapeutic music environments possess structural elements that support autonomy, encourage the freedom of expression, and promote interaction of patients with their environment. Music engagement is then used to reduce stressful conditions or mitigate risk situations.,e7

Research Question and Supporting Data for MBI Hypothesis Testing

MBI research should be built on evidence from prior studies, extant literature, and/or clinical practice. Music and health researchers can benefit from the experience of researchers in behavioral intervention development, which highlights the importance of systematic reviews and the need to use basic research to inform selection of theoretical models while maintaining clinical equipoise. Furthermore, the initial literature review should also include a focus on components of the intervention itself—for MBIs, this focus would include musical elements, such as frequency, tempo, melody, and playback volume, as well as nonmusical intervention components (e.g., imagery that accompanies the music), which are important to engage hypothesized mechanisms or produce the desired outcomes.

MBI Building Blocks and Common Data Elements

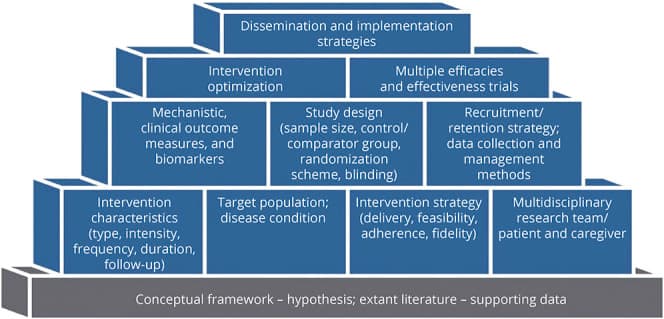

The essential components of an MBI include the intervention itself; the mode of delivery; the target population; a study design, which distinguishes the MBI's effects from those of socialization during the experience; and data collection and management. Figure 2 provides examples of various building blocks that should be incorporated in the planning and implementation of MBI studies.

Figure 2. Examples of Building Blocks for MBIs.

Intervention

When defining the intervention, investigators should consider specific elements of music (e.g., pitch, timbre, or rhythm), modes of engagement such as actively performing and creating music or passively listening to music, the relationship between culturally specific music preferences and outcomes, patient demographics, and contextual factors. In the earliest stage of the research, parameters such as dose and frequency should be treated as experimental variables to be manipulated to enhance efficacy. Furthermore, longer, lower intensity interventions, and/or the inclusion of booster sessions may be important to maintain the desired treatment response. In this paper, we define the building blocks of the MBI in the context of a research setting—the rationale, clinical population, and the aim of the study will be determined by the research question.

Protocol Delivery

A systematic review of music intervention trials reported that less than half of those studies examined treatment fidelity (i.e., the extent to which an intervention is implemented consistently across practitioners and trial sites). Similar findings were noted in the 2020 AHRQ/NASEM report. Critical considerations about the delivery methods for MBI studies include: (1) music characteristics (e.g., live vs recorded, music genre, personalized vs nonpersonalized, and patient selected vs investigator selected); (2) research setting (e.g., laboratory, clinic, or community); (3) mode of participation (e.g., individual vs group, in-person vs remote delivery); (4) timescale (e.g., short vs long term, session length and intensity, follow-up frequency, or potential for habituation); (5) staffing and support (e.g., expert therapists vs wide range of providers with appropriate training); (6) resources and organization (e.g., cost, scheduling, or assessments); and (7) feasibility, accessibility, and adherence. These considerations are equally important to objectively establish the intensity of the intervention needed to observe clinical improvements and maximize dissemination and implementation of the intervention.

Study Population

The study population is the subset of the target population available for a study (e.g., individuals diagnosed with early-onset dementia from a group of nursing home residents). MBI investigators must have a strong rationale for testing a specific intervention in any given population, for example, the choice of the target population might focus on disorder subtypes or severity, ability to conduct convenience sampling in a pilot study, availability of a control group in a randomized trial, or the relative importance of studying time courses longitudinally. Additional pragmatic considerations include accessibility to the population, its stability over time, and the resources available in the setting where the intervention will be tested. In addition, screening of patients to eliminate confounding variables, such as hearing loss or amusia, is advisable.

Control Groups or Comparators

Although control groups or comparators may not always be needed for early-phase research, they are crucial for randomized controlled trials. The goals of a study and the research question should drive the selection of the comparator group. Devising the appropriate control condition for music studies is complex, and current MBI research has poorly designed control conditions. For MBI studies, control conditions may include a music element such as a slowed-down version of the same music, meaningless sounds, or nature sounds or, instead of a music element, the control may be an audiobook. The investigative team needs to consider whether the chosen control condition is intended to control for intervention effects that are unrelated to the music (e.g., attention, sound stimulation, visual stimulation, and shared experience) or for effects of the specific intervention protocol delivery method (e.g., recorded music listening vs guided or tailored music listening). Moreover, control conditions must match the test intervention in intensity of engagement and observation (controlling for the Hawthorne effect). Equally important is controlling for a possible placebo effect by matching the test intervention in the intensity of the treatment delivered.

The optimal comparator is one that will provide the clearest answer to the primary research question or the strongest test of the trial's primary hypothesis. The rationale for the comparator choice should focus on the primary purpose of the trial and not be weakened by lesser considerations or arbitrary rules. An NIH expert panel issued a useful framework for considering and justifying control groups with the Pragmatic Model for Comparator Selection in Health-Related Behavioral Trials.

Potential Outcome Measures and Biomarkers: Examples for Brain Disorders of Aging MBIs

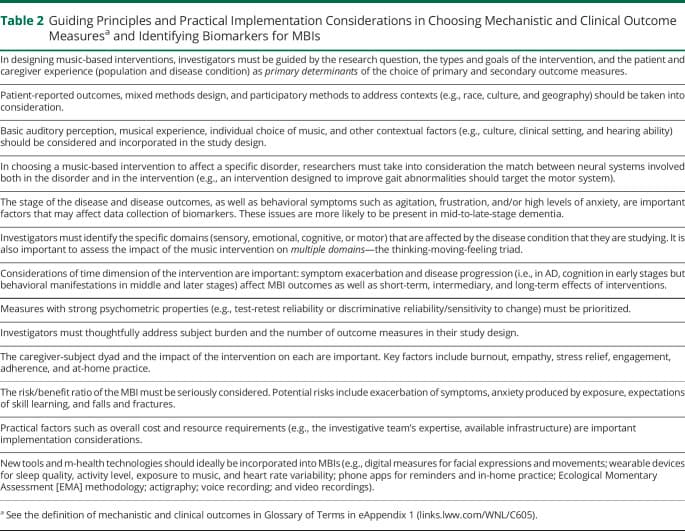

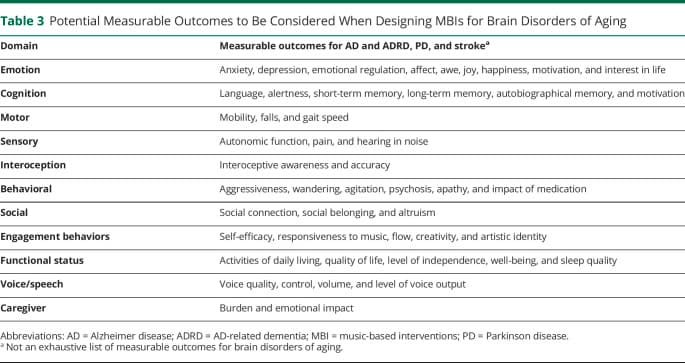

MBIs for brain disorders of aging, including AD/ADRD, PD, and stroke, provide some of the most compelling evidence for music's health benefit and create a model for future work across the lifespan. The NIH MBI Toolkit, developed through discussions with our expert panels, suggests core datasets of outcome measures and biomarkers for brain disorders of aging that researchers may select for their MBI studies. Some guiding principles and factors that merit consideration when selecting these outcome measures and biomarkers are listed in Table 2.

Mechanistic and Clinical Outcome Measures

The essential steps in developing hypotheses on the impact of MBIs for brain disorders of aging include adopting a conceptual framework for the outcomes to be measured; choosing the appropriate study design; identifying relevant domains for proximal (short-term) and distal (long-term) outcomes, boundary conditions (i.e., moderators), and mechanisms (i.e., mediators); and determining the relevant biomarkers. For each domain, a range of measurement modalities is possible, including self-report, performance-based measures, direct observation, sensor technology measures, physiologic monitoring, and various functional brain measures, each of which has strengths and weaknesses for assessing the domain of interest. Therefore, multimodal assessment of a given domain is often preferable (Table 3).

Mechanistic and clinical outcomes may be derived from studies using an intervention in healthy subjects or individuals with a specific disease/condition to better understand the clinical aspects of human biology and/or disease. More specifically, mechanistic outcomes provide insights into biological or behavioral processes, the pathophysiology of a disease, or an intervention's mechanism of action. Clinical outcomes are measurable changes from an objective baseline in health, function, or quality of life that results from a treatment or intervention.

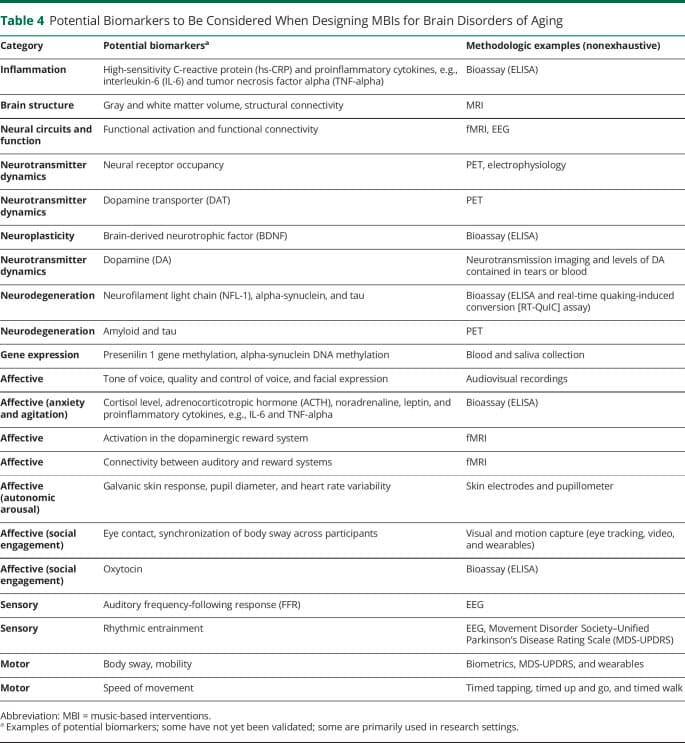

Biomarkers

A biomarker is a defined characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, a pathogenic process, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention. Biomarkers can be used to parse out the causally active components of an intervention and provide insights not just into whether an intervention works but also how it works. Biomarkers can indicate susceptibility or risk; predict or measure a condition or response; assess safety; or be used for diagnosis, prognosis, or monitoring.

Brain disorders of aging are complex conditions affecting numerous biological, behavioral, and cognitive-affective systems. As such, a wide array of biomarkers can be considered when designing MBIs for brain disorders of aging, including inflammation, brain structure, neurologic functioning, gene expression, affect, sensory and motor activity, stress markers (e.g., galvanic skin response, pupillometry, and cortisol) (Table 4).

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Advancement in science is predicated on 2 critical concepts: rigor in designing and performing scientific research and the ability to reproduce biomedical research findings. In 2016, the NIH announced the Rigor and Reproducibility Policy to better ensure that researchers use unbiased and well-controlled experimental design, methodology, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of results. Furthermore, the policy encourages scientific integrity, public accountability, and social responsibility.

MBIs are a valuable therapeutic opportunity because these interventions are low cost, mostly devoid of side effects, often scalable in health care systems, and generally well accepted by patients. The development and dissemination of the NIH MBI Toolkit addresses a pressing need in the music and health field for enhanced data collection, with guidelines for scientifically rigorous studies, representing a necessary step in accelerating progress toward incorporating MBIs in health care systems.

Rigorous MBI research also requires a team science approach, bringing together different groups with varied expertise, perspectives, and ideas. To be successful, the investigative team should be interdisciplinary and have expertise in the population or health condition of interest, intervention development, target outcomes (e.g., functional, biological, disease, and nondisease outcomes), neuroscience, and relevant biomarkers. The team should include a methodologic expert(s); statistician; competent clinician(s) to deliver the intervention; stakeholders (e.g., patients or caregivers); skilled study coordinator(s) to supervise recruitment, data collection, adherence to the study protocol, and data management; and an individual with experience managing funded research. Utilization of the guiding principles of the NIH MBI Toolkit is strongly recommended for NIH-funded studies of MBIs.

Final Points and Next Steps for MBIs

MBIs have the potential to influence patient-relevant target outcomes, such as manage symptoms, slow disease progression, rehabilitate, and improve quality of life in many disease conditions across the lifespan. A critical step toward incorporating MBIs into US health care systems is the dissemination and implementation of the NIH MBI Toolkit's guiding principles for large-scale, rigorous, and replicable evidence-based research. Table 5 outlines other key take-home messages from this manuscript.

Development of the NIH MBI Toolkit has highlighted the utility of various technologic advances in behavioral measurement that are enabling more rigorous and robust measurements to be obtained. Among these advances are the Item Response Theory and computer adaptive testing, which are at the core of both the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) and the NIH Toolbox. These systems are relevant across conditions and were developed and evaluated using state-of-the-science psychometric methods. The NIH Toolbox, which has more than 100 standalone measures including many cognition measures, is particularly useful. Aspects of the NIH Toolbox and PROMIS can complement the NIH MBI Toolkit and are freely available, although technology fees are required when tests are administered digitally.

Other advances include Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), which involves intensive sampling over time, often obtained through smartphones or text messaging (rather than retrospective self-report) and passive sensor technologies (e.g., smartphones, wearable sensors, or home-based sensors). EMA can also leverage advances in neuroscientific tools, which provide very dynamic and detailed pictures of neurocircuitry and how it changes over time.

In addition, the Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools Resource glossary, developed by the US Food and Drug Administration and the NIH, clarifies terminology and uses of biomarkers and endpoints, as they pertain to progression from basic biomedical research to medical product development to clinical care. This resource creates unique opportunities for novel biomarker development specific to the music and health field. For example, auditory biomarkers derived from an EEG and the auditory frequency-following response could be used to screen or stratify cohorts in an MBI study. Other useful tools and measures include psychometrically sound and validated measures of music engagement, flow, creativity, and joy. Digital measures of facial expressions and movement, as well as innovative personalized music delivery systems, would further enhance the ecologic validity of MBI protocols.

Finally, the NIH foresees potential research opportunities for future modification and updating of the NIH MBI Toolkit relevant to various diseases and conditions across the lifespan. The research community is strongly encouraged to take advantage of this Toolkit to help improve the rigor and replicability of MBIs