Adults have been concerned about adolescent impetuosity for centuries. The rashness of youth has been blamed for many teenage indiscretions, from juvenile delinquency to unprotected sex and substance use. At the turn of the 21st century, research on the development of self-control in adolescence added functional brain imaging as a complement to behavioral tasks and self-report questionnaires, but the essential question has remained the same: Why do teenagers have so much difficulty controlling their impulses? As a report in PNAS by van den Bos et al. (1) attests, the question continues to be of interest. Although we discuss some potential limitations, the study these authors describe adeptly and cleverly incorporates the broad armamentarium of tools, including self-report, behavior, brain function, and both structural and functional connectivity measures, to move us toward a more complete answer to the question.

It is important to put the contributions of van den Bos et al. (1) in historical context. Ten years ago, the pat explanation for adolescent impulsivity was the immaturity of the prefrontal cortex. Adolescents behave impulsively, it was thought, because the brain circuitry necessary to exert top-down control over urges originating in the limbic system was still developing. Studies of brain anatomy revealed important changes over the adolescent decade in both gray and white matter volumes in prefrontal regions, suggesting that synaptic pruning and myelination were enabling more efficient and more effective self-regulation.

As adolescent brain science progressed, scientists interested in adolescent self-regulation began to turn their attention to regions other than the prefrontal cortex. One possibility, some suggested, was not simply that cognitive control was immature, but that this immaturity was accompanied by a temporary intensification of urges to pursue novel and rewarding experiences (2, 3). This so-called “dual systems” or “maturational imbalance” perspective on adolescent decision-making has not gone uncriticized (4), but it remains a widely used theoretical model guiding the study of adolescent risk-taking.

More specifically, we and others have proposed that adolescents’ disposition toward risk is because of a maturational imbalance between a brain network involved in deliberative, planful, and goal-directed behavior and one involved in affective processes, including the anticipation and valuation of incentives (2, 5). Shortly after puberty, the affective processing system undergoes rapid development, producing increased sensitivity to (and motivation for) reward that declines through late adolescence and into the early 20s. In contrast, structures of the cognitive-control network that inhibit impulses and direct motivation toward goal-relevant behaviors show continued gains into the 30s.

If adolescent risk-taking is the byproduct of an easily aroused incentive-processing system and a still-immature cognitive-control system, it is reasonable to ask how important the contributions of each are to teenagers’ impulsive behavior. Many risky situations force a choice between taking a gamble to receive a highly salient immediate reward (e.g., the sensation of unprotected sex) and waiting for a safer but less-rewarding one (e.g., using a condom). Is choosing the immediate reward because of teenagers’ difficulties regulating their desires, or is it because their desires are especially intense?

Although the authors frame the problem in slightly different terms, distinguishing between these two accounts is the focus of the van den Bos et al. (1) paper. It is an important question, but it is an exceptionally challenging one because simply observing an individual’s behavior does not provide a clear-cut answer. Consider, for example, a child who has been given the famous Marshmallow Test (6), in which he is asked to choose between receiving one marshmallow immediately or waiting for two. Does the child who chooses the delayed reward of two marshmallows have especially strong self-control, or is he just not particularly fond of marshmallows? Observing the child cannot answer the question. Perhaps looking into his brain can.

To address this issue, van den Bos et al. (1) use an intertemporal choice task in which individuals must choose between a small monetary reward given sooner and a more generous one given later. As we and others have reported in previous studies (7), van den Bos et al. (1) find that adolescents are more likely than adults to opt for smaller rewards sooner (SS) than larger ones later (LL). The authors posit that the extent to which individuals are inclined toward SS choices indexes impatience, which they view as one of three aspects of impulsivity (the other two are acting without thinking and sensation-seeking). There is some debate about how best to define impulsivity and its underlying factors (8), and to us it makes more sense to view impatience not as a third aspect of impulsivity, but as the byproduct of poor self-control and high reward sensitivity (in this framing, impatience can be either hasty or considered). Nevertheless, in a realm of inquiry where nomenclature is muddy, the distinction between volitional processes that invoke cognitive control and motivational processes fueled by reward-seeking is helpful.

The chief contribution to the literature in the van den Bos et al. (1) study is its examination of the link between age differences in intertemporal preferences and patterns of structural and functional connectivity. Through an elegant series of analyses that combine task performance, self-reports, diffusion tensor imaging-based tractography, and functional activation and connectivity measures, this single study ties together past findings and helps to narrow the gap in our understanding of how brain development affects the inclination and ability to think toward the future. Specifically, having demonstrated that adolescents are more likely than adults to choose SS than LL offers, van den Bos et al. then ask whether teenagers’ tendency to discount the future is because of their greater reward sensitivity or weaker self-control. The authors examine this in three ways: (i) they correlate subjects’ intertemporal preferences with self-reports of “present hedonism” and “future orientation,” (ii) with patterns of brain activity, and (iii) with measures of structural and functional connectivity. Because van den Bos et al. find that intertemporal preferences are correlated with self-reported future orientation but not hedonism, that the choice of LL over SS rewards is associated with increased engagement of frontoparietal control circuitry, and that improvements in frontostriatal connectivity mediate the link between age and intertemporal preferences, the authors conclude that adolescents’ intertemporal preferences are driven by weak cognitive control rather than heightened reward sensitivity.

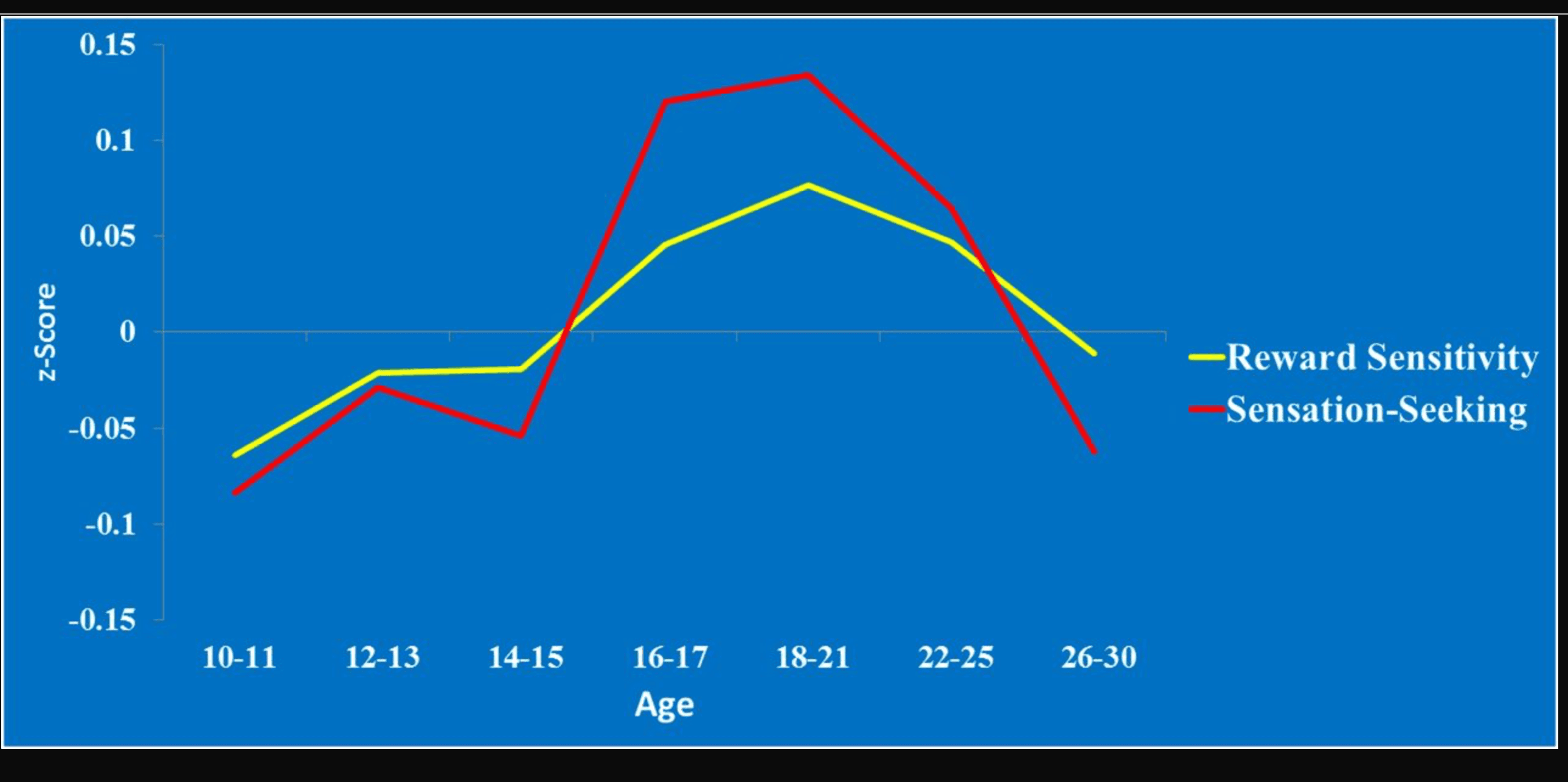

We think the evidence in support of this conclusion is intriguing, but that some potential limitations should be acknowledged. One problem concerns the self-report measure of reward sensitivity. In the van den Bos et al. (1) study, reports of present hedonism and age are uncorrelated, which is both surprising and at variance with a large literature on age differences in reward sensitivity. Many previous studies, including our own, have found a strong, curvilinear relationship between reward sensitivity and age, with sensitivity increasing between preadolescence and mid-adolescence and declining thereafter (9). We have demonstrated this pattern using behavioral measures of reward sensitivity (subjects’ rate of change in choices from advantageous decks during the Iowa Gambling Task) and self-reports of sensation-seeking (10), both in an American sample and in a recently completed study of more than 5,000 individuals from 11 countries (Fig. 1). The curvilinear relationship between reward sensitivity and age is also well documented in the developmental neuroscience literature, in which most (though not all) studies show that activation in the brain’s reward centers is greater during adolescence than before or after (11). The lack of a relationship between self-reported hedonism and age in the van den Bos study (1) is compounded by the limited variability in scores on this subscale, unlike future orientation scores, which are predictably and linearly related to age (see figure 1D in ref. 1). Intertemporal choices may be more strongly correlated with self-reported future orientation than hedonism simply because there is variability in the former but not the latter.

Fig. 1. Age differences in reward sensitivity (from the Iowa Gambling Task) and self-reported sensation seeking in a sample of more than 5,000 individuals from 11 countries.

A second issue regards the way in which van den Bos et al. (1) examine brain activity as a function of intertemporal preferences. The analysis of functional activation, which produced the coefficient values and regions that were used in further analyses, was based on a contrast of trials in which participants chose the LL option versus those in which they chose the SS option. Although this is an informative strategy to identify the brain regions that contribute to intertemporal preference, there is a catch: the SS offers came in two flavors, split evenly: those in which the reward could be earned immediately (on the day of the session) and those in which the participant would still have to wait 14 d. As a result, the comparison of all LL trials to all SS trials (including both types of offer) is biased to pick up on regions that are influential in the selection of larger delayed rewards (i.e., cognitive control areas), and will not readily detect regions that activate selectively in response to immediately available rewards (i.e., limbic regions that signal reward sensitivity/present hedonism). It therefore is not surprising that the van den Bos et al. identified only regions that were more strongly active when the LL option was chosen, and none that were more strongly active when the SS option was taken, a finding that shapes their conclusion that the maturation of self-regulatory processes is more explanatory of age-dependent changes in impatience. In an earlier study of adult intertemporal choice, by one of the article’s authors, the critical involvement of limbic areas in guiding choice was made apparent by contrasting trials for which an immediate reward was available to all other trial types (12). This is an important analysis that didn’t make its way into the current paper (1). The authors conclude that it is “increased control, not sensitivity to immediate rewards, that drives developmental reductions in impatience,” but the latter construct may not have been adequately assessed (1).

Finally, van den Bos et al. (1) argue that, because the degree of frontostriatal connectivity observed is correlated with a stronger preference for LL choices, and that this connectivity increases with age, it must be weaker cognitive control that accounts for adolescents’ relatively greater propensity for SS choices. The authors provide evidence in support of this hypothesis by showing that there is a significant indirect pathway linking age and intertemporal preferences that is mediated by the strength of connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the medial striatum. This finding is certainly consistent with the authors’ argument and, in our view, is an especially interesting and important finding in the paper. Still, we don’t know whether the direct relationship between age and discounting is eliminated—or merely diminished—when connectivity is taken into account. If it is the latter, it is possible that the connection between age and temporal discounting may be partially mediated by changes in cognitive control, but partially mediated by changes in reward sensitivity as well; as the authors acknowledge in their introduction to the study, it does not have to be one or the other.

Our understanding of the neural underpinnings of adolescent impulsivity is an important topic with both scientific and practical implications, an understanding that has been meaningfully advanced by the van den Bos et al. report (1). The authors are to be commended for venturing into waters that are conceptually very muddy. In the final analysis, they have certainly helped to clarify these waters but, of course, a good amount of sediment still remains to be sifted through.