Abstract

MDMA (i.e., 3,4-methylenedixoymethamphetamine), commonly known as “Ecstasy” or “Molly,” has been used since the 1970s both in recreational and therapeutic settings. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designated MDMA-Assisted Therapy (MDMA-AT) as a Breakthrough Therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 2017, and the FDA is requiring an additional phase 3 trial after rejecting the initial New Drug Application in 2024. Unlike other psychedelics, MDMA uniquely induces prosocial subjective effects of heightened trust and self-compassion while maintaining ego functioning as well as cognitive and perceptual lucidity. While recreational use in nonmedical settings may still cause harm, especially due to adulterants or when used without proper precautions, conclusions that can be drawn from studies of recreational use are limited by many confounds. This especially limits the extent to which evidence related to recreational use can be extrapolated to therapeutic use. A considerable body of preliminary evidence suggests that MDMA-AT delivered in a controlled clinical setting is a safe and efficacious treatment for PTSD. After a course of MDMA-AT involving three MDMA administrations supported by psychotherapy, 67%–71% of individuals with PTSD no longer meet diagnostic criteria after MDMA-AT versus 32%–48% with placebo-assisted therapy, and effects endure at long-term follow-up. This review primarily aims to distinguish evidence of recreational use in nonclinical settings versus MDMA-AT using pharmaceutical-grade MDMA in controlled clinical settings. This review further describes the putative neurobiological mechanisms of MDMA underlying its therapeutic effects, the clinical evidence of MDMA-AT, considerations at the level of public health and policy, and future research directions.

MDMA (±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), otherwise known in recreational settings as “Ecstasy” or “Molly,” is primarily being studied as an augmenting agent to psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Eight randomized clinical trials that included a total of 171 participants randomized to receive MDMA at starting doses of 75 mg–125 mg (with a supplemental half-dose 90–120 minutes later) in comparison to 126 participants randomized to receive an inactive placebo or up to 40 mg of MDMA found that at higher doses, MDMA-Assisted Therapy (MDMA-AT) was an efficacious treatment for PTSD, with moderate to large between-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d=0.70–0.91) and large within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d=1.95–2.10) (1–3). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designated MDMA-AT as a Breakthrough Therapy in 2017, which is reserved for treatments that may represent substantial improvement over current treatment options (4). FDA-approved Expanded Access (colloquially known as “Compassionate Use”) began in 2022, allowing for greater access to open-label MDMA-AT outside of clinical trials and within FDA-regulated treatment settings. Although the FDA declined to approve the New Drug Application of MDMA-AT for the treatment of PTSD due in large part to limitations in study design of the Phase 3 trials, the FDA invited a New Drug Application resubmission after another Phase 3 trial is conducted that addresses previous study design limitations. As this modality emerges as a potential treatment option, clinicians will need to be equipped with a deeper understanding of MDMA and MDMA-AT to adequately counsel patients on this topic.

The landscape of evidence for MDMA and MDMA-AT can be generally divided into two distinct categories: 1) evidence that overall supports the potential harm of “Ecstasy,” “Molly,” or MDMA in nonclinical settings, and 2) evidence that overall supports the potential benefits and limited risk of harm of MDMA-AT using pharmaceutical-grade MDMA in controlled clinical settings. There are inherent risks in overgeneralizing the promising evidence of MDMA-AT in clinical settings to mistakenly underestimate the risks of harm and overestimate potential benefits of use in nonclinical settings. Conversely, there are also inherent risks in overgeneralizing the unfavorable evidence of use in nonclinical settings to mistakenly overestimate the risks of harm and underestimate the benefits of MDMA-AT in clinical settings.

This review primarily aims to make a clear distinction between the evidence of “Ecstasy,” “Molly,” or MDMA in nonclinical settings versus MDMA-AT using pharmaceutical-grade MDMA in controlled clinical settings. This review will also discuss the neurobiological mechanisms of MDMA underlying its therapeutic effects, the clinical evidence of MDMA-AT, considerations at the level of public health and policy, and future research directions.

History of MDMA and MDMA-Assisted Therapy

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 by Anton Köllisch, a chemist working for the pharmaceutical company Merck, as a precursor to a hemostatic agent (5). However, its psychoactive properties remained unrecognized for several decades. The first known synthesis of MDMA to study its potential for clinical use was a 1953 study contracted by the U.S. Army Chemical Corps and conducted by the University of Michigan (6). This was an animal toxicology study to estimate safe doses of MDMA and several other similar substances such as 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), a metabolite of MDMA (7). While MDA would later be used in government-funded research, there is no record of MDMA being studied or administered to humans by the government (8).

MDA, an entactogen similar to MDMA, was patented in 1960 to treat anxiety and was used throughout the 1960s–1970s both recreationally and as an adjunct to psychotherapy, similar to how MDMA-AT is conducted today (6, 9). Once MDA was made a Schedule I substance by the passage of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, MDMA first surfaced that same year on the streets of Chicago as an unscheduled recreational alternative to MDA (6). Alexander Shulgin, a pioneer of the chemistry of psychedelic and entactogenic compounds, also facilitated the synthesis of MDMA during this period and began self-trials with MDMA in 1976 (6). In 1977, Shulgin introduced it to retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Leo Zeff, an Oakland, California psychotherapist with years of experience in MDA-assisted therapy throughout the 1960s. Zeff went on to train approximately 150 therapists and legally treat over 4,000 patients with MDMA-AT until 1985, when MDMA was declared a Schedule I substance with no accepted medical use due to the rise of its use in recreational settings (5).

The first report of the clinical use of MDMA was also published in 1985, and it involved a summary of proceedings from a gathering of 35 clinicians and researchers experienced in the use of MDMA (10). The report described that MDMA “reduced defensiveness and fear of emotional injury, thereby facilitating more direct expression of feelings and opinions, and enabling people to receive both praise and criticism with more acceptance than usual… Many subjects experienced the classic retrieval of lost traumatic memories, followed by the relief of emotional symptoms (10).”

Given that by 1985 MDMA had been used for therapeutic purposes to treat various psychiatric conditions for over a decade, court proceedings were initiated to determine if there was a more appropriate scheduling for MDMA than a Schedule I substance with “no accepted medical use.” Supporting data included clinical findings of safety and efficacy presented by MDMA-AT therapists (11). The DEA administrative law judge presiding over the case ultimately determined that “the evidence of record requires MDMA to be placed in Schedule III” (12) – meaning that MDMA has an accepted medical use and low to moderate risk of physical dependence or high psychological dependence (13). Despite this ruling, the DEA determined in 1986 that MDMA should remain Schedule I with no accepted medical use for reasons that remain unclear.

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a nonprofit organization, was subsequently founded in 1986 by Rick Doblin in response to the DEA Schedule I determination. The primary effort of MAPS has been building an evidence base toward FDA-approval of MDMA-AT for PTSD. All the randomized placebo-controlled Phase 2 and 3 studies conducted of MDMA-AT for PTSD have thus far been sponsored by MAPS (Figure 1). The MAPS Public Benefit Corporation, which was their drug development entity, was rebranded as Lykos Therapeutics prior to their submission of the New Drug Application in early 2024.

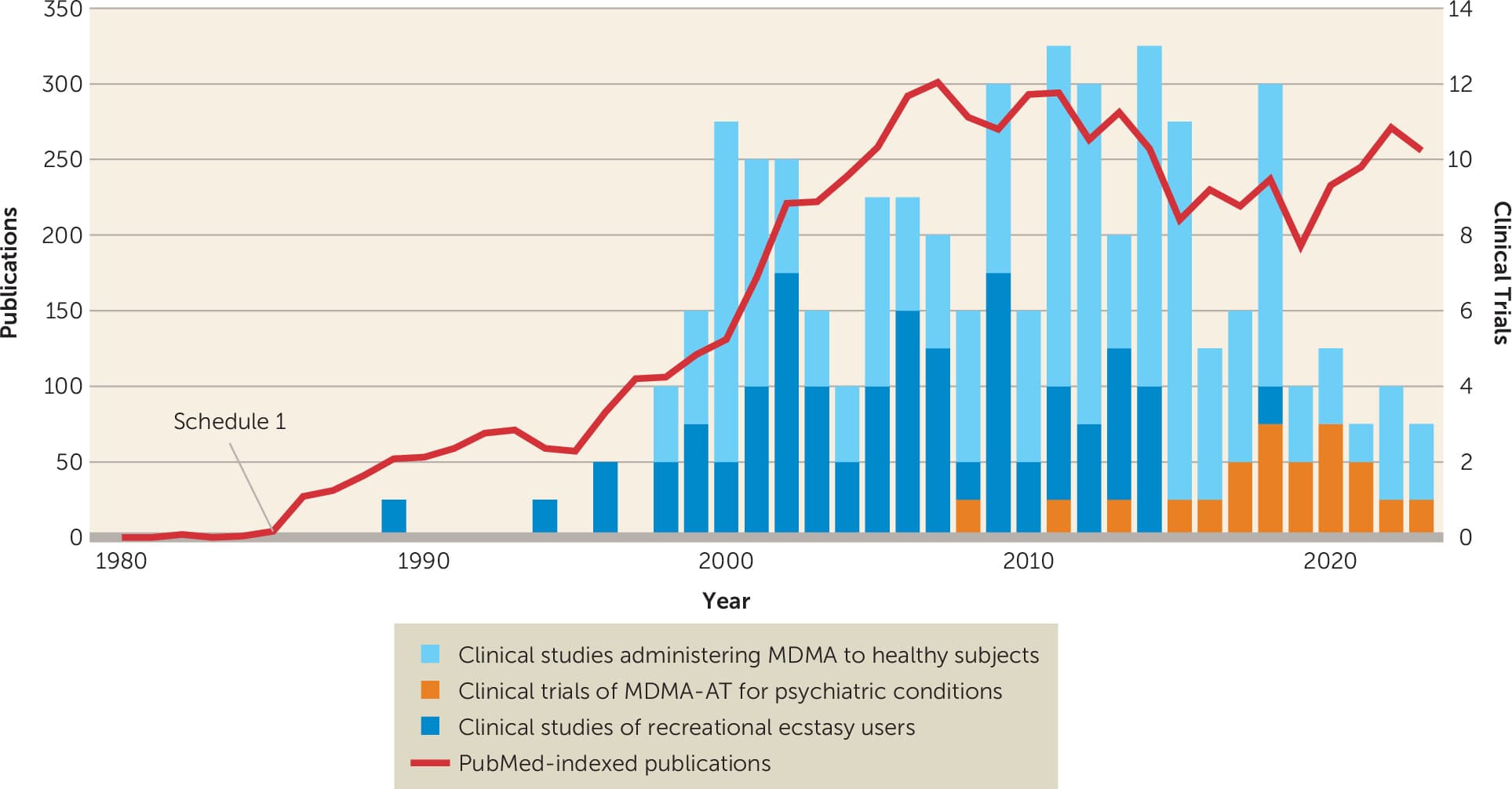

Figure 1. MDMA publications and clinical trialsa

a. Publications and clinical trials involving individuals who had used recreational Ecstasy, healthy individuals administered pharmaceutical-grade MDMA, and individuals with psychiatric conditions provided MDMA-AT.

MDMA: What It Is and What It Is Not

Classification and Subjective Effects

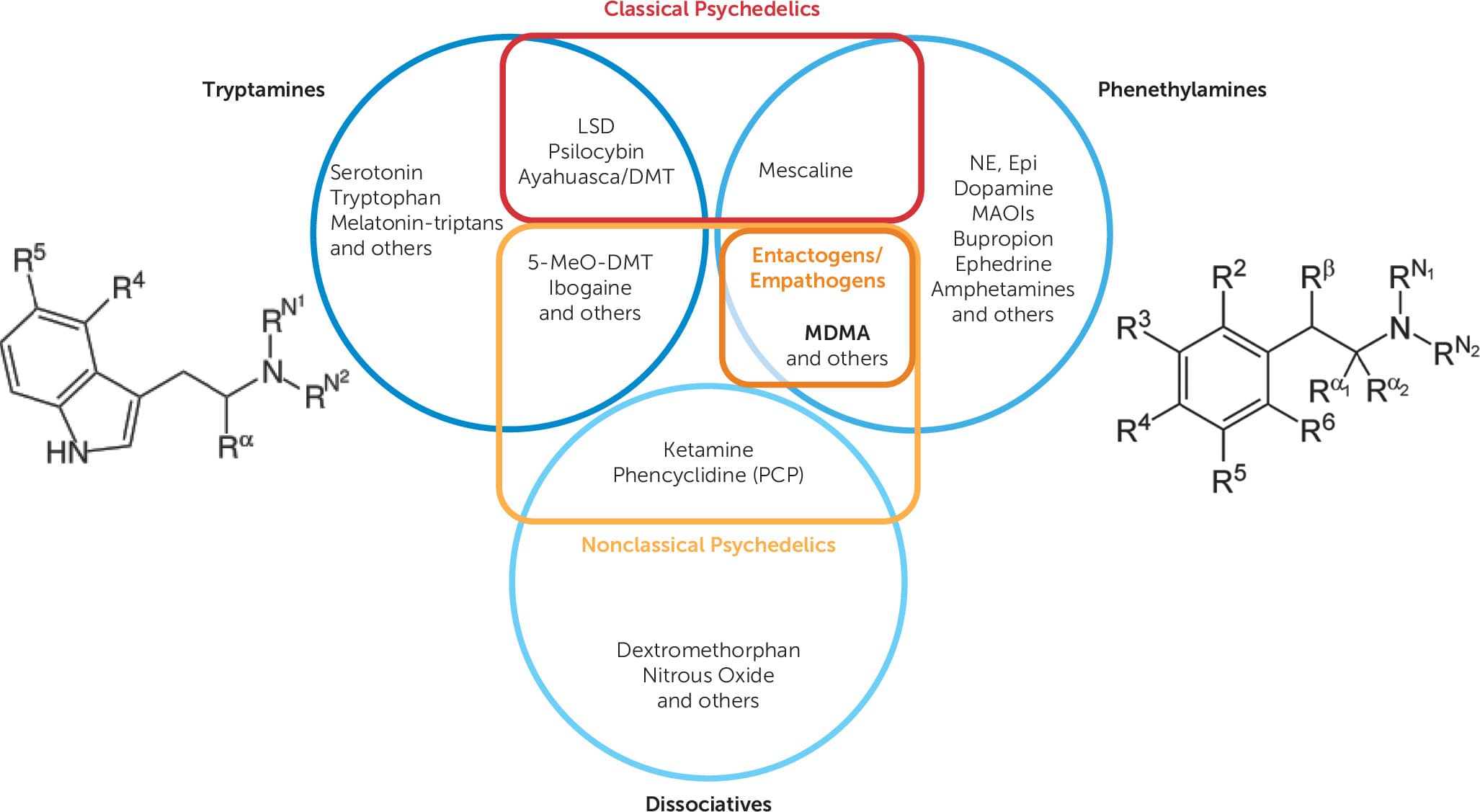

MDMA is variably considered a psychedelic (Figure 2), meaning “mind manifesting.” Many common preconceptions and connotations from popular culture associated with psychedelics often refer to the classical psychedelics, which are distinct from MDMA. The most common classical psychedelics are lysergic acid diethylamide (“LSD” or “acid”) and psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”) (15). Classical psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin are known to cause vivid visual perceptual phenomena (16), mystical or spiritual experiences (17), a dissolution of the ego or sense of self (18), and a sense of unity or interconnectedness with all else (19).

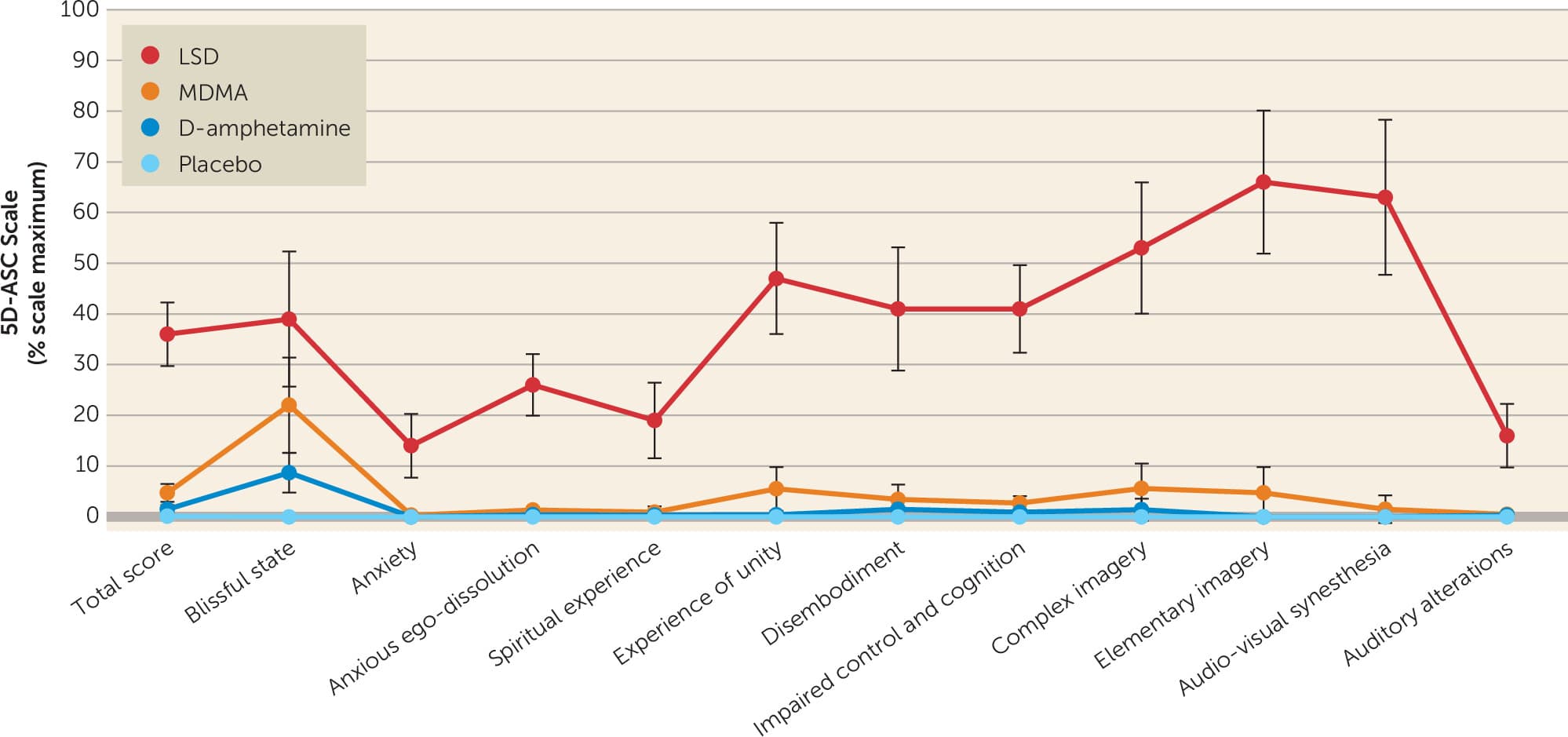

MDMA at therapeutic doses does not markedly produce the aforementioned subjective effects that are characteristic of classical psychedelics (Figure 3) (20). Although MDMA at therapeutic doses is potentially associated with mild transient depersonalization or derealization phenomena, it does not produce visual perceptual phenomena or panic reactions that are more strongly associated with classical psychedelics (21). MDMA instead produces a state of positive mood, well-being, and extroversion that is not attenuated by the serotonin (5HT)2A/C antagonist ketanserin (22). Thus, MDMA should not be considered a classical psychedelic because 5HT2A agonism is the primary mechanism of action characteristic of classical psychedelics (23), and the subjective effects of MDMA are not attenuated by a 5HT2A antagonist (22).

The first academic publication of the clinical effects of MDMA was the 1985 proceedings from a meeting of 35 experts that included experienced researchers and clinicians (10). The report included a comparison of the subjective effects of MDMA and LSD that noted “[u]nlike LSD, MDMA does not essentially cause perceptual or cognitive distortions or loss of ego control. MDMA consistently promotes a positive mood state, while LSD promotes mood swings that can be extreme and unpredictable. MDMA’s principal effects last 3–5 hours, those of LSD last 6–14. The clinicians agreed that MDMA was much easier to use than LSD, and because MDMA did not threaten ego control, involved little psychological risk to a naïve subject. While LSD subjects sometimes experience transient delusional states, the only complications of using MDMA, according to the clinicians and researchers, are occasional anxiety and various physical symptoms due to the drug’s sympathomimetic effects (10).”

More rigorous modern studies have corroborated many of the claims in the initial 1985 report. Notably, a randomized, double-blind, cross-over study of 28 healthy participants who received LSD (100 μg), MDMA (125 mg), D-amphetamine (40 mg), and inactive placebo at least 10 days apart found that the subjective effects of MDMA are more comparable to D-amphetamine than to LSD (Figure 2) (20). Unlike with LSD, perceptual and cognitive lucidity remain intact with both D-amphetamine and MDMA (20). The primary differences that separate MDMA from other commonly prescribed amphetamines are the additional subjective effects of bliss and self-compassion, as well as prosocial effects including heightened empathy, trust, compassion, and sense of connectedness to others (20, 24). Notably, a study comparing separate clinical trials of MDMA and methamphetamine in healthy subjects suggests MDMA and methamphetamine may have comparable effects on prosocial perceptions of social connection (25). Furthermore, MDMA has been found to increase feelings of self-reported sociability (26), to enhance implicit and explicit emotional empathy for positive emotional stimuli more so in men than in women (27, 28), to reduce rejection of unfair offers in a partnered economic decision-making game (29), and to enhance attention to positive social cues and pleasantness of experienced affective touch (30).

Thus, MDMA is better classified as a nonclassical psychedelic and more specifically, an empathogen or entactogen (Figure 2). Empathogen refers to a core feature of MDMA to “generate empathy.” Entactogen is the more widely accepted term referring to the way in which MDMA allows an individual to “touch within” through a lens of inner-directed self-compassion (31). MDMA’s entactogenic characteristics are thought to be a core feature of its therapeutic effects when paired with psychotherapy (32).

Figure 2. Classification of tryptamines, phenethylamines, and dissociatives as classical psychedelics, nonclassical psychedelics, or neithera

a. Adapted from Wolfgang and Hoge (14). DMT: dimethyltryptamine; 5-MeO-DMT: 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine; NE, norepinephrine; Epi, epinephrine; R: a carbon or hydrogen atom.

Figure 3. Comparative subjective effects of LSD, MDMA, D-amphetamine, and placebo on the 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC) scalea

a. Doses were 100 μg oral for LSD, 125 mg oral for MDMA, and 40 mg oral for D-amphetamine versus inactive placebo. Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. Adapted from Holze et al. (20).

Objective Effects

MDMA elicits acute sympathomimetic effects including elevated blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and pupillary dilation (2, 20, 33, 34). MDMA at doses of 75–125 mg in healthy participants elicits temporary hypertension (33% of participants) and tachycardia (29%) and increases body temperature >38°C (19%) (33). MDMA exhibits dose-dependent effects, such that higher doses and plasma blood concentrations are associated with greater elevations in hemodynamic response (33, 34). Because MDMA is primarily metabolized by CYP2D6, CYP2D6 activity is inversely related to MDMA plasma concentrations (34), subjective drug effects (35), and blood pressure (35) after MDMA administration.

A randomized, double-blind, cross-over study comparing MDMA (125 mg), LSD (100 μg), D-amphetamine (40 mg), and inactive placebo in healthy participants found that the three active drugs had comparable increases in hemodynamic response, body temperature, and pupillary dilation (20). Compared to D-amphetamine, however, MDMA and LSD had comparably greater increases in heart rate and lesser increases in blood pressure (20). Overall, MDMA produces a constellation of sympathomimetic effects that are well-tolerated but must still be accounted for in clinical contexts.

Pharmacology and Neuroscience

Classical psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin are believed to primarily act through 5HT2A receptor agonism, which underlies their psychedelic effects as well as most of their behavioral and neural effects (36–40). MDMA also is predominantly serotonergic, but in contrast to classical psychedelics, MDMA blocks serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine reuptake in descending order of affinity and degree of elevation of extracellular transmitter levels (41, 42).

Oxytocin may also be an important mediator underlying some of MDMA’s effects (43). For several hours after MDMA administration, plasma oxytocin reaches levels up to four times greater than baseline (44), an effect that is unique to MDMA and not observed with LSD or D-amphetamine (20). In a rodent model, MDMA induces oxytocin release via 5-HT activation of presynaptic 5-HT4 receptors on oxytocin neurons, and subsequent activation of oxytocin receptors in the nucleus accumbens reopens the age-related closure of a critical period of neuroplasticity that temporarily enhances social reward learning (43). This oxytocinergic effect may underlie feelings of greater trust (45), openness to social reward and connectedness (43), and modulate encoding of stimuli as aversive versus neutral (46). However, MDMA and oxytocin differ in some ways in their behavioral effects. While MDMA tends to have direct prosocial effects as reviewed above, oxytocin may increase the intensity of both positively and negatively valenced social connections. As a result, in some cases, oxytocin may aggravate mistrust and social conflict (47–49). Thus, although oxytocin may contribute to the observed effects of MDMA, it seems unlikely that oxytocin fully mediates MDMA effects.

Reductions in the fear response with MDMA are supported by decreased activity in the amygdala in response to socially threatening stimuli during MDMA administration (26). When MDMA is administered to rodents during reconsolidation of an extinguished cue-shock association, the learning of the new safety memory is strengthened (50). Likewise, in humans, MDMA administered after threat conditioning and prior to extinction training results in a greater proportion of individuals demonstrating extinction retention 2 days later relative to inactive placebo (51).

Safety of MDMA and MDMA-Assisted Therapy

“Ecstasy” Versus MDMA

Especially when discussing safety profiles, a clear distinction must be made between recreational “Ecstasy” used in nonclinical settings versus pharmaceutical-grade MDMA used in controlled clinical settings.

MDMA itself is considered to have a low risk of dependence and harm relative to many other prescribed and nonprescribed substances (52, 53). However, the risks are greater with Ecstasy, which often does not contain pure MDMA and is typically taken in uncontrolled, nonclinical environments. Approximately half of Ecstasy pills contain adulterants such as cocaine, amphetamines, or fentanyl, and some pills may not contain MDMA at all (54, 55). Many cases of toxicity in the literature attributed to MDMA are in fact not confirmed by laboratory testing to be MDMA, but rather, they depend on patient or collateral report of Ecstasy use, which is often confounded by other substances (56–58). Thus, conclusions drawn from studies of Ecstasy used in nonclinical settings cannot be directly translated to pharmaceutical-grade MDMA administered in a controlled clinical setting.

Neurotoxicity

Through popular media, MDMA was once thought to “put holes in your brain.” These reports reflected concerns specifically related to detrimental effects of MDMA on dopamine and serotonin neurons. However, the 2002 study (59) that formed the basis of this belief was later retracted due to the lab having been found to inject their primates with methamphetamine instead of MDMA (60). The original findings could not be reproduced when the study was replicated with confirmed MDMA (60).

Other animal studies have reported neurotoxic injury to a subset of serotonin neuronal axons in rodents and primates with doses of 2.5–40 mg/kg (175–2,800 mg if extrapolated to a 70-kg mammal) injected subcutaneously up to twice daily for up to 4 consecutive days (61–66). However, humans in controlled clinical research settings are dosed orally approximately 1 month apart with therapeutic doses of approximately 1.7 mg/kg (120 mg for a 70-kg person) and with a supplemental half-dose approximately 2 hours later to prolong the peak effect (2, 3). Therapeutic range doses up to 1.5 mg/kg in healthy human participants in clinical research settings have been found to be unlikely to be neurotoxic to serotonergic neurons, considering no detectable effects on 5-HT uptake has been measured using positron emission tomography at these doses (67). At concentrations closer to therapeutic levels, MDMA in fact promotes neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis—the formation of new branching and interconnections between neurons (68).

In a study of chronic recreational users of MDMA—many of whom also used other substances and who had used recreational MDMA on approximately 228 occasions with an average dose of 386 mg—reductions in ligand binding to 5-HT transporters (SERT) and reduced neuroendocrine response to tryptophan suggest reduced SERT density and neuronal function after chronic recreational MDMA use (69). A later study found decreased SERT density only in female subjects who had used >50 MDMA tablets recreationally over their lifetime, but there were no statistically significant decreases in SERT density in male subjects regardless of the amount of lifetime recreational MDMA use (70). In this same study, female subjects who had reported remaining abstinent from using recreational MDMA for over 1 year had SERT densities that were significantly higher than female subjects with >50 lifetime MDMA tablets but not higher than controls (70). Thus, chronic heavy use of MDMA in recreational settings may lead to decreases in SERT density that may be reversible and normalize over time.

Mortality

It is estimated that approximately 500,000 doses of MDMA were administered in clinical settings with no known instances of mortality before MDMA was first declared a Schedule I substance in 1985 (71, 72). However, in recreational nonclinical settings, the risk of death for a first-time use of Ecstasy is between 1 in 2,000 and 1 in 50,000 (73, 74). Out of 81 deaths of individuals who used recreational drugs and were found to have MDMA in their system at the time of death, two deaths per year were confirmed to involve only MDMA (73). All other deaths included other substances, with opiates being involved in the majority (59%) of cases (73).

The two most common causes of death related to Ecstasy use are hyperthermia and hyponatremia (75), both of which are a direct result of use in recreational settings characterized by high temperatures, physical exertion, and a lack of appropriately balanced fluid and electrolyte intake. Hyperthermia and hyponatremia both are preventable in controlled clinical settings. Altogether, deaths involving Ecstasy use are rarely a direct result of MDMA itself. Instead, cases of death are typically compounded by other substances, hyperthermia, hyponatremia, the environment, or underlying medical conditions—the risks for all of which are directly minimized in controlled clinical settings and through careful pre-screening and assessment.

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia (body temperature >40°C) and its sequelae are, by far, the most common cause of morbidity and mortality related to recreational Ecstasy use, with 183 total reports in the literature (76). All these cases comprise individuals who used Ecstasy in nonclinical settings. Therapeutic doses of MDMA can lead to an increase in body temperature of 0.2–0.8°C, which is typically clinically insignificant (77). Ecstasy-related hyperthermia is thought to be multifactorial, due to a combination of high doses of MDMA, other substances, vigorous physical exertion, high ambient temperature, crowded conditions, and reduced fluid intake—all of which are commonplace in recreational settings (78–81). The following precautions are implemented in controlled clinical settings to limit the risk of hyperthermia: MDMA is only provided at therapeutic dosages, interacting substances are screened for, physical activity is minimal, ambient temperature is controlled, and fluids are available and frequently encouraged. With these precautions in place, there have been no known instances of clinically significant hyperthermia in clinical trials of MDMA or MDMA-AT (1–3, 77).

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia and its sequelae are another cause of morbidity and mortality related to Ecstasy use in nonclinical settings, with 26 total reports in the literature (76). This is due to MDMA-induced syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) combined with voluntary compensatory overhydration, as many recreational users will overhydrate in an attempt to address the commonly known risk of hyperthermia without proper awareness of the risk of hyponatremia (82). MDMA releases antidiuretic hormone (ADH), which leads to fluid retention and decreased serum sodium concentration (83). When this is combined with compensatory overhydration to combat dehydration, individuals can develop dangerously low sodium concentrations that can ultimately lead to seizures and death. This risk is mitigated in clinical settings by screening for electrolyte abnormalities prior to treatment and moderating fluid intake with balanced electrolyte content during treatment. With these precautions, clinically significant hyponatremia has not occurred in clinical trials of MDMA or MDMA-AT (1–3, 76).

Cardiovascular Conditions

Cardiovascular conditions and their sequelae are the final higher risk category of morbidity and mortality associated with Ecstasy use in nonclinical settings, with 27 total reports of such cases in the literature (76). However, not all cases toxicologically confirmed the presence of MDMA, and many involved other substances (76). Similar to other amphetamines and classical psychedelics, MDMA has sympathomimetic properties that result in elevated heart rate and blood pressure (21), which can increase the risk of cardiovascular events in those with premorbid vulnerabilities (84). In healthy individuals receiving at least 100 mg of MDMA, blood pressures remained below the hypertensive threshold of 140/90 mmHg in 95% of cases (21, 85). Risks of precipitating cardiovascular events are mitigated in clinical settings with careful pretreatment screening with a detailed medical history and electrocardiogram (ECG), frequent blood pressure and vital sign monitoring during treatment, and ensuring blood pressure medications are available, if necessary.

Since an estimated 500,000 doses of MDMA were administered in unregulated clinical settings before 1985 (71, 72), at least another 1,775 individuals have received a dose of MDMA in controlled clinical research settings to date (76). Of these, there have been no documented cases of clinically significant hyperthermia, hyponatremia, or related conditions. However, there was a single instance whereby a participant was medically observed overnight after developing chest discomfort during his last of five MDMA sessions (76). He had already received two blinded low-dose control sessions of MDMA-AT (a 30-mg initial dose plus a 15-mg supplemental dose 2 hours later) and two open-label high-dose sessions of MDMA-AT (a 125-mg initial dose plus a 62.5-mg supplemental dose 2 hours later), with no symptoms until his fifth MDMA session. He developed chest discomfort that safely resolved after a single dose of metoprolol and overnight medical observation in a hospital setting before being discharged the next day. He was confirmed to have premature ventricular contractions (PVC), which is a benign arrhythmia that commonly can occur with exercise, caffeine, or other substances. A single PVC that was detected on his initial screening for the study had at the time been determined to be benign, and thus he was permitted to enroll.

Cardiac screening criteria for MDMA-AT have since become more stringent to mitigate the risk of similar cases from recurring. Considering this participant had already received four doses—two low-dose and two high-dose—without incident, further studies may be warranted to investigate the safety and efficacy of moderate doses (80 mg plus a supplemental half dose 2 hours later) in those with benign cardiac conditions, given that 75 mg (plus a supplemental half dose 2 hours later) has been found to be the lowest dose still potentially efficacious for PTSD (86).

5-HT2B-mediated valvular heart disease (VHD) also warrants clinical consideration. 5-HT2B receptors are highly expressed within the fibroblasts that maintain the structural homeostasis of cardiac valves (87). Several 5-HT2B agonist medications such as methysergide, ergotamine, and fenfluramine have been associated with VHD (87, 88). MDMA is also a 5-HT2B agonist (89). A case-control study of 33 individuals with chronic Ecstasy use versus 29 age- and gender-matched controls found that eight chronic Ecstasy users (28%) had VHD compared to none in the control group (90). Those with clinically relevant VHD had a higher cumulative dose of Ecstasy (mean 943 tablets) than those without clinically relevant VHD (mean 242 tablets) (90). For comparison, a full course of treatment in clinical trials of MDMA-AT involves two to three MDMA sessions total (1–3). Although no clinical trials administering pharmaceutical-grade MDMA have been found to lead to long-term cardiac complications including 5-HT2B VHD (76), the potential for cardiac adverse effects must still be taken into account—especially in real-world clinical implementation where patients may eventually receive a total number of doses that are beyond what has been studied thus far in clinical trials.

Psychiatric Conditions

Depression, anxiety, and psychosis are additional potential concerns with Ecstasy in nonclinical settings compared to MDMA in controlled clinical settings. In a review of 199 case reports of nonclinical Ecstasy use, approximately 20% reported psychiatric concerns (91). Symptoms of anxiety and depression, in particular, have been associated with non-clinical Ecstasy use (92, 93). However, anxiety and depression have a stronger association to polydrug use overall compared with any single particular substance (94–97). Cannabis may have greater adverse psychiatric sequelae when compared with Ecstasy (98, 99). The extent to which these associations can be translated from nonclinical to clinical settings is limited, given the high variability of the contents of illegally obtained Ecstasy, involvement of other substance use, usage patterns in nonclinical settings, environmental factors, and possible pre-existing psychiatric conditions prior to Ecstasy use.

A 14-year prospective study of children followed into adulthood found that individuals who had used Ecstasy in adulthood were twice as likely to have had depression or anxiety in childhood (100). Thus, it is difficult to establish causal associations between Ecstasy use and psychiatric conditions, given that individuals predisposed to psychiatric conditions may be more likely to use Ecstasy and other substances in nonclinical settings.

In clinical settings, brief anxiety reactions can occur and are often self-limited within the MDMA-AT session. However, as adverse effects, there is no difference in frequency of anxiety reactions between active and placebo groups during and after a session of MDMA-AT in controlled clinical settings (101).

Seventeen percent of individuals receiving MDMA-AT have also been found to have an increased likelihood of low mood compared with placebo during a dosing session (101). In contrast, there was a nonsignificant improvement in depression over an entire treatment course when pooling all four phase 2 clinical trials of MDMA-AT that measured depression (1), and significant improvements in depression were found in the first phase 3 multisite clinical trial (2). Depression symptom outcomes were collected but not reported for the second phase 3 clinical trial (3).

Current evidence does not indicate increased risk for suicidal ideation or behavior. In studies of MDMA-AT for PTSD, six participants had suicidal behavior and a seventh was hospitalized for suicidal ideation. However, six of the seven participants were either in the placebo arm or prior to receiving any active MDMA (1–3).

Symptoms of psychosis associated with Ecstasy use in nonclinical settings have been reported (102, 103). However, these cases are susceptible to the same confounds that limit the generalizability of conclusions drawn between the nonclinical use of Ecstasy and the clinical use of MDMA. There are no reported instances of psychosis due to MDMA in controlled clinical settings (1–3, 86, 104–112). This is likely due to limiting MDMA dosages to therapeutic ranges, ensuring a therapeutic setting, and careful medical screening and monitoring.

While there is weak evidence suggesting a positive bidirectional relationship between nonclinical Ecstasy use and psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety (92, 93, 100), such relationships have not been observed with MDMA-AT in controlled clinical settings. Stronger evidence provided by clinical trials of MDMA-AT for PTSD suggest that for carefully screened individuals from this patient population, anxiety and psychosis are not long-term sequelae of the treatment, depression may improve, and serious suicidality is primarily found in those who do not receive the active treatment (1–3).

Neurocognition

The body of literature regarding the impact of Ecstasy use on neurocognitive performance is overall conflicting and has substantial methodological limitations. Many studies rely on retrospective design, unmatched controls, and cohorts confounded with polysubstance use and occasionally ongoing substance use. Conclusions that can be drawn from these studies are further limited by reliance on self-report without being able to confirm the reported identity, amount, and frequency of use of Ecstasy and other substances.

A prospective cohort study of Ecstasy-naïve individuals with new Ecstasy use found no differences in attention, working memory, visual memory, and visuospatial functioning after initiating Ecstasy use (113). The new Ecstasy use group were found to have lower scores of verbal memory, but they were still in the normal range and not corrected for multiple testing (113). However, no differences in verbal memory were detected when using age- and gender-matched controls (114).

One study found that individuals actively using Ecstasy had significant impairments in various types of memory, although impairments were not associated with amount of lifetime Ecstasy use (115). A conflicting study found memory impairments only in heavy use (≥80 lifetime Ecstasy tablets) compared to moderate use (<80 lifetime Ecstasy tablets) or controls (116). This study also found no differences between moderate use and controls in any measures of neurocognition to include executive function, working memory, planning, and cognitive impulsivity (116).

While many studies attribute neurocognitive impairments to Ecstasy use despite being confounded by concomitant substance use, one study concluded that neurocognitive impairments were in fact not associated with Ecstasy use but rather with polysubstance use (117).

Experimental studies administering MDMA to healthy volunteers have likewise produced no evidence for acute impairments in neurocognitive functions. Individuals under the influence of MDMA displayed no appreciable changes in inhibitory control during a go/no go paradigm (118), nor did MDMA impair selective attention as measured by a Stroop paradigm (21).

All three clinical trials of MDMA-AT for PTSD that included a neurocognitive battery (106, 109, 119) showed no change in neurocognition after a course of treatment (1).

Overall, the literature is equivocal in terms of the relationship between Ecstasy use and neurocognition, given the methodological limitations inherent in such studies. However, the literature is unequivocal that MDMA-AT delivered in a controlled clinical setting has no negative effects on neurocognition (1). Whether this relates to differences in population demographics/history, purity of the compound, adulteration with other substances, or the fact that most recreational use studies include individuals with a far greater number of lifetime ingestions remains to be elucidated.

Addiction

Despite primarily being serotonergic, MDMA also has mild pro-dopaminergic properties which confer at least a theoretical potential for dependence (120). Animal studies suggest that MDMA has rewarding properties, although significantly less than other substances such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or heroin (121–126). Chronic administration of high doses of MDMA in mice does not induce physical dependence (127). This aligns with findings in humans that approximately three-fourths of individuals who use Ecstasy in nonclinical settings use it less frequently than once per month, often infrequently on special occasions (128).

While evidence for the addictive properties of MDMA is equivocal, some evidence indicates MDMA may have the potential to treat addiction. MDMA-AT may reduce alcohol use in patients with PTSD (129). An open-label clinical trial of individuals with heavy alcohol use who recently completed detox suggests MDMA-AT potentially may be an effective treatment for individuals diagnosed with alcohol use disorder (110).

In a sample of 83 patients with PTSD who received MDMA-AT, eight had reported use of Ecstasy between the end of their course of MDMA-AT and 12-month follow-up (129). Of those eight, six had used Ecstasy prior to the study and thus did not constitute new use. Nearly all, including the two individuals without prior use, had attempted to self-administer Ecstasy in a nonapproved setting for therapeutic purposes. However, additional Ecstasy use was not reported after the initial nonapproved session, as participants reported they found it to be therapeutically ineffective without trained clinical support.

Overall, although Ecstasy is one of the most commonly used recreational substances globally (130), the risk of dependence is low compared with other recreational substances (52, 53). The risk of future nonprescribed use after receiving MDMA in a controlled clinical setting is also low but must still be considered and mitigated (112, 129). Given new nonprescribed Ecstasy use after MDMA-AT clinical trials has primarily been for therapeutic purposes in uncontrolled settings, this suggests that an important component of mitigating future nonprescribed use after a course of MDMA-AT would be to facilitate greater access to legal MDMA-AT for individuals requiring ongoing treatment. In this way, individuals are less incentivized to self-administer nonprescribed Ecstasy for therapeutic use in nonapproved and potentially unsafe settings, and instead, access to legal treatment will be able to better meet the demand from patients seeking continued treatment.

Serotonin Syndrome

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by the use of substances leading to overactivation of serotonin pathways in the central and peripheral nervous systems (131). Serotonin syndrome and potential mortality may result from coadministration of MDMA and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (132–134). However, the combination of MDMA with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor paradoxically diminishes the clinical effects of MDMA and does not lead to serotonin syndrome in either rodent models (135–137) or humans (138). This is because the entry of MDMA into the presynaptic terminal is inhibited by serotonin reuptake inhibitors (139). Out of 20 cases of serotonin syndrome involving confirmed or presumed MDMA reported to the FDA since 2004, none of the cases involved MDMA as the only ingested substance (140). All 20 cases involved other substances—the most common being amphetamines (140). Despite the paradoxical attenuation of effects when co-administering MDMA with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, MDMA still carries a risk for serotonin syndrome with MAOIs and other serotonergic medications (141). This risk has thus far been successfully mitigated in clinical trials involving MDMA (140) by ensuring at least five half-lives of a washout period between the last dose of a serotonergic medication and the dose of MDMA.

Relational Safety

The term “relational safety” is intended to encompass the domains of potential harm and associated safeguards within the relationship dynamic between the patient and other individuals, particularly the co-therapists. MDMA-AT and other psychedelic-assisted therapies involve potential risks to relational safety that must be accounted for and mitigated to the maximum extent possible. The use of therapeutic touch in MDMA-AT and other psychedelic-assisted therapies is an unresolved question in terms of the balance between its potential benefits and harms. Additional risks to relational safety also include the heightened potential for sexual abuse (142), interpersonal dependency, and suggestibility.

Therapeutic touch.

In alignment with the MDMA-AT treatment manual, therapeutic touch is occasionally offered as a form of support during an MDMA session in a manner that is discussed with the participant beforehand. The aim is to find an individualized balance between enhancing therapeutic support while respecting the participant’s boundaries and comfort. Therapeutic touch typically entails a momentary holding of the participant’s hand, arm, or shoulder in a supportive manner. The pleasantness of therapeutic touch is selectively enhanced by MDMA but not by methamphetamine or placebo (30, 143), and it serves to help ground the participant through challenging moments during the medication session. While therapeutic touch may be clinically advantageous to an extent that is yet uncertain, it also comes with additional risks that must be mitigated, namely the possibility of boundary violations in the form of sexual touch and abuse.

Overall, the use of therapeutic touch in MDMA-AT and other psychedelic-assisted therapies remains an open question in terms of precisely where to set the threshold of allowable therapeutic touch to optimize the balance between its potential benefits and harms. In the absence of any clinical trials designed to investigate this question, the current established threshold described above is thought to strike an optimal balance between potential benefit and harm: a momentary holding of the participant’s hand, arm, or shoulder during therapeutically appropriate times with precise boundaries agreed upon between the participant and therapists beforehand.

Sexual abuse.

An important domain of relational safety with MDMA-AT—and any psychedelic-assisted therapy—is the potential for sexual abuse. Contributing factors may include a combination of readjusted therapeutic boundaries due to the acceptance of therapeutic touch, the uneven power dynamic inherent in the therapeutic relationship, an unendorsed loosening of ethical standards on the part of the therapist, and the acute effects of the MDMA, which may amplify the risks associated with each of the aforementioned factors due to the patient’s acutely heightened levels of trust and emotional vulnerability. With this heightened risk to relational safety also comes a need for heightened ethical safeguards detailed further in the online supplement.

There have been at least two documented instances of sexual contact related to MDMA-AT prior to 1985 when MDMA-AT was still legal in clinical settings (5) and at least one instance since then in a clinical trial in Canada (144). The most recent incident in Canada involved a participant in an MDMA-AT clinical trial where the unlicensed male therapist initiated non-intercourse intimate physical contact with the female study participant in the form of caressing and cuddling during the MDMA session, which evolved into a sexual relationship outside of the study sessions. These forms of physical contact are not permitted in the MDMA-AT manual. A civil case between the participant and co-therapists was resolved out of court in 2019 with terms that are not public (145). Detailed accounts surrounding this incident are publicly available both from the perspective of the participant (146) and the study sponsor (144).

While allowing therapeutic touch may present additional risks for unethical behavior, these risks are significantly mitigated in modern times by numerous layers of safeguards, several of which were not in place until the current wave of clinical trials and have since been strengthened in response to the most recent case in Canada. Further elaboration of the many layers of ethical safeguards now in place can be found in the online supplement.

Interpersonal dependency.

Interpersonal dependency refers to “a complex of thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors revolving around needs to associate closely with valued other people” (147). Although our review did not identify evidence of interpersonal dependency with MDMA-AT published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, there are nonscientific reports suggestive of interpersonal dependency described by at least two MDMA-AT clinical trial participants, one of whom was described as feeling “desperately dependent on her therapists” after her course of MDMA-AT had completed (146). Given that interpersonal dependency is both a known component of several psychiatric diagnoses and can be anticipated as a component of the natural course of treatment in traditional therapy (148), it is yet unclear to what extent the incidence and character of treatment-emergent interpersonal dependency may differ between MDMA-AT and traditional therapy. Although the MDMA-AT treatment modality allows for interpersonal dependency and other relational dynamics to be processed as an aspect of integration therapy, further research is still needed to identify potential areas of risk for treatment-emergent interpersonal dependency and to develop strategies that may further mitigate potential harm.

Suggestibility.

Suggestibility is “an individual’s susceptibility or responsiveness to suggestion (149).” While LSD administered to healthy participants has been found to increase suggestibility (149), MDMA has been found to not increase suggestibility in healthy participants (150). Also, MDMA, D-amphetamine, and placebo all scored <1% of the maximum score for “impaired control and cognition” compared with 41% for LSD (20) (Figure 3), suggesting that cognitive control remains intact with MDMA compared with a classical psychedelic. Nevertheless, considering the attenuated fear response and enhanced prosocial effects associated with MDMA (151), more studies are needed to accurately profile the potential risks of suggestibility with MDMA-AT that might increase a patient’s vulnerability to unintended or even intended harm.

Summary: Safety of MDMA and MDMA-AT

Conclusions and preconceptions drawn from the use of Ecstasy in nonclinical settings need to be clearly distinguished from the use of MDMA in controlled clinical settings. Ecstasy in nonclinical settings can indeed be harmful and even fatal on rare occasions without appropriate precautions. In contrast, the use of pharmaceutical-grade MDMA at therapeutic dosages with appropriate precautions in clinical settings with trained professionals appears to be safe.

Risk of addiction or future nonprescribed use is low when MDMA is administered in a clinical research setting. Whether the low likelihood of future nonprescribed use changes with increased access to MDMA secondary to potential FDA approval remains to be assessed. Although chronic heavy use of recreational Ecstasy may be associated with impaired neurocognition, therapeutic MDMA in controlled clinical settings has not been found to impair neurocognition. The factors dictating these differences are currently not well understood, although impurity and unknown dosages of recreational Ecstasy almost certainly play a role. The three most common causes of morbidity and mortality associated with nonclinical Ecstasy use are hyperthermia, hyponatremia, and cardiac conditions. However, the factors that confer an increased risk of morbidity and mortality with nonclinical Ecstasy use can be mitigated when using pharmaceutical-grade MDMA in controlled clinical settings with appropriately trained providers, proper screening and assessment, and fidelity to standard precautionary measures. MDMA-AT in FDA-approved clinical settings allows for appropriate dosing, assurance of purity, preventing physical overexertion, maintaining appropriate body temperature with a temperature-controlled environment, moderated/balanced fluid and electrolyte intake, thorough medical screening and oversight, and availability of specially trained therapists to facilitate an optimally safe and therapeutic process. When combining all these factors, MDMA-AT in an FDA-approved clinical setting with all appropriate safeguards in place appears to be medically and psychiatrically safe.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy

Treatment Course

MDMA-AT primarily consists of three distinct types of sessions: preparatory, MDMA, and integration sessions. A treatment course involves two to three MDMA sessions. Each MDMA session is 6–8 hours long and is approximately 1 month (±1 week) apart. Preceding the first MDMA session are three 90-minute preparatory sessions designed to educate the participant about the treatment, build a therapeutic alliance, and establish therapeutic aims.

Each MDMA session is followed by three 90-minute integration sessions for a total of six to nine integration sessions per course of treatment. The first of each trio of integration sessions occurs the morning after the MDMA session. The second and third integration sessions follow at approximately 1-week intervals but prior to the next MDMA session.

Each MDMA session involves two doses of MDMA. The first dose of each MDMA session is a full dose ranging from 75–125 mg (80–120 mg in the most recent phase 3 trials and likely in real-world clinical implementation). The second supplemental dose is half of the initial dose and is offered 90–120 minutes after the initial dose as an option based on tolerability, patient preference, and therapist clinical judgment. In MDMA-AT clinical trials, participants were offered and in nearly all cases accepted the supplemental dose. The purpose of the timing and dosage of the supplemental dose is to extend the peak effect of the MDMA.

Note: the prevailing convention used not only in this paper but also throughout the MDMA-AT literature is that stated doses typically refer to the initial dose with the implied understanding that a supplemental half dose was offered and likely administered 90–120 minutes after the initial dose, unless stated otherwise. All stated MDMA doses that appear throughout this paper should be assumed to be followed by a supplemental half dose 90–120 minutes later if the MDMA dose is mentioned in the context of MDMA-AT. For example, if it is stated that participants in an MDMA-AT study arm were offered 80 mg of MDMA, it should be assumed that they were initially offered 80 mg and an additional 40 mg 90–120 minutes later for a cumulative dose of 120 mg for that dosing day. This assumption is not applicable when an MDMA dose is mentioned in a context outside of an MDMA-AT study.

Therapeutic Modality

The therapeutic modality of MDMA-AT is derived fundamentally from elements of a person-centered, process-oriented approach that endeavors to establish a dynamic of trust, respect, and supportive self-discovery while providing nondirective support. As long as these elements are prioritized, the treatment manual entrusts the content and technique of therapeutic engagement to be guided by the therapist’s prior psychotherapeutic training. Details of the therapeutic modality practiced in the preparation, medication, and integration sessions are further described in the online supplement.

MDMA-AT classically involves the participant working with a female-male co-therapist pair, which has since become the gold-standard model of psychedelic-assisted therapy (152). The reason for a female-male co-therapist pair is 1) to better ensure the comfort and safety of the participant, 2) to maintain a therapeutic connection with the participant if one therapist must briefly leave the room, and 3) to allow for gender-specific therapeutic dynamics to develop and be processed, such as transference/countertransference dynamics (5). However, the adherence to this gender split is more recently being questioned, and newer trials have also incorporated two co-therapists of the same gender (107). Although the currently established MDMA-AT modality is the most well-studied approach, other approaches have yet to be rigorously studied.

MDMA-AT for PTSD

Efficacy.

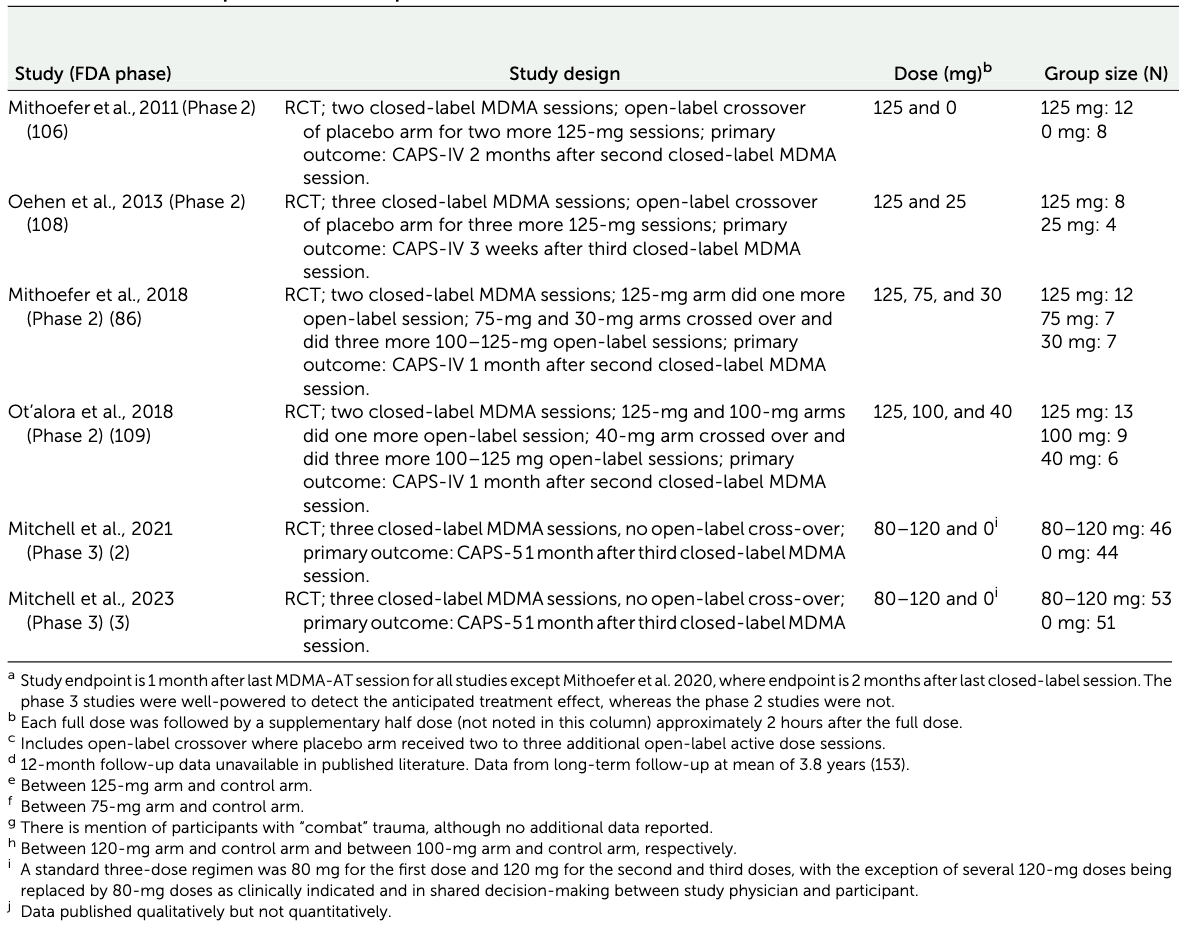

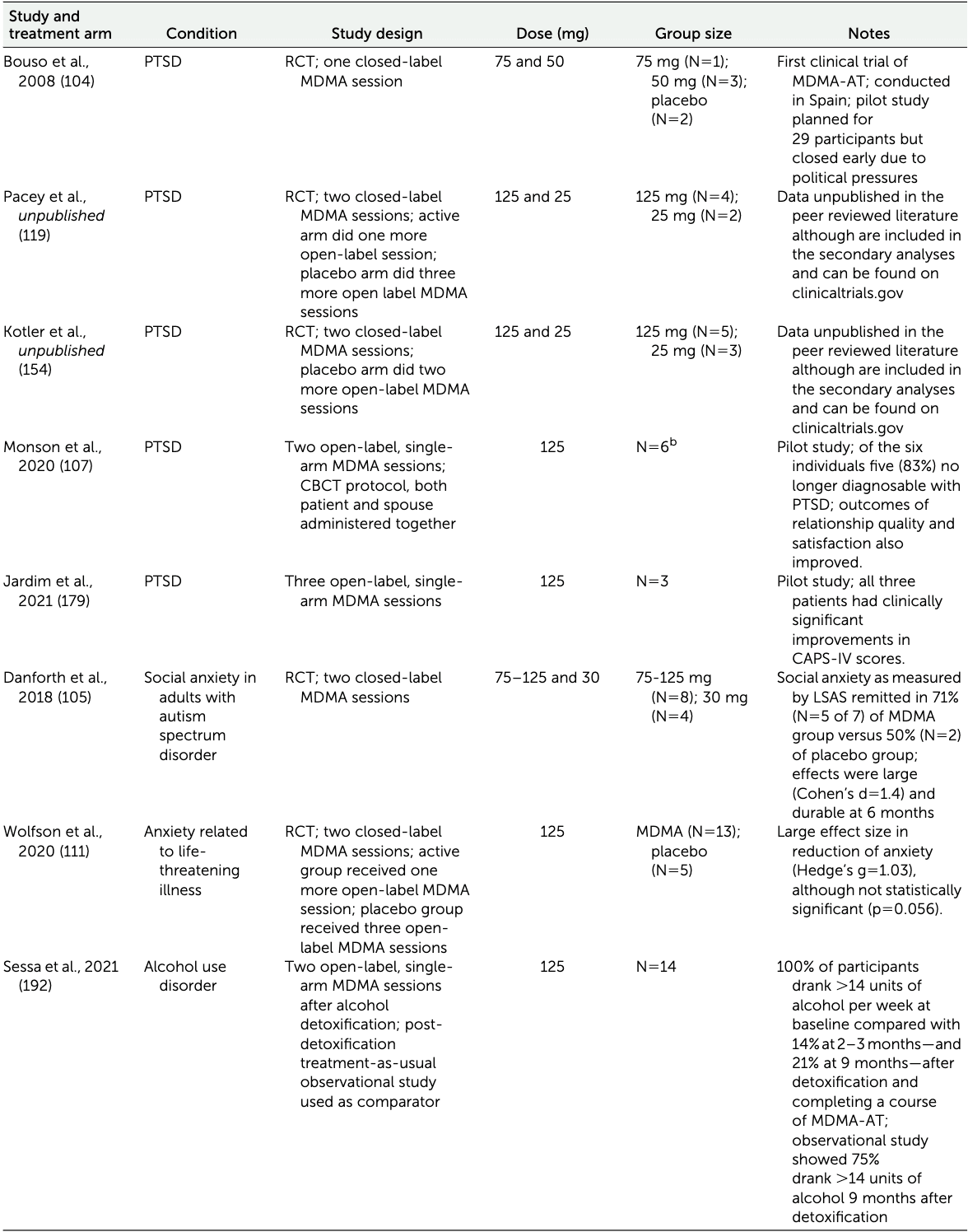

Nearly 300 study participants have received MDMA-AT for PTSD across eight randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials (Table 1) (2, 3, 86, 106, 108, 109, 119, 154). Participants had a diagnosis of PTSD for 14–18 years on average, and the illness for nearly all was resistant to previous therapies (1–3).

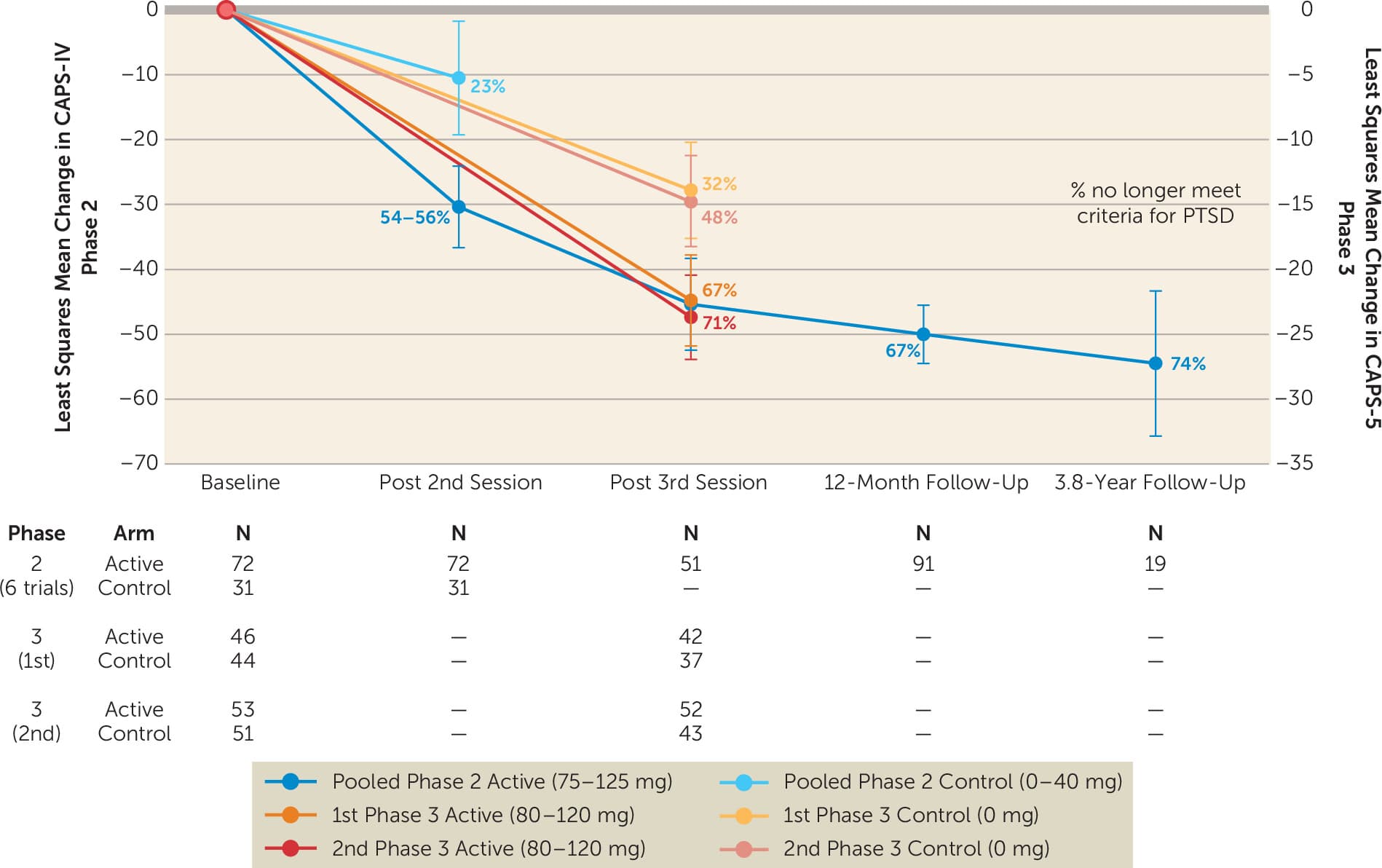

At the primary study endpoint (approximately 4 weeks after the last of three MDMA doses) across both phase 3 multicenter clinical trials, 67%–71% of individuals lost the diagnosis of PTSD after a course of MDMA-AT versus 32%–48% with placebo-assisted therapy (between-group: Cohen’s d=0.70–0.91; within-group: d=1.95–2.1; Figure 4) (2, 3). In phase 2 studies, loss of diagnosis rates significantly further improve at 1-year follow-up (129) and remain durable, with 74% no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD nearly 4 years later (Figure 4) (153).

Remission (defined as loss of PTSD diagnosis and Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 total score ≤ 11) was achieved by 33% of the active group and 5% of the placebo group in the first phase 3 trial (2) as well as 46% of the active group and 21% of the placebo group in the second phase 3 trial (3). Dropout rates across both phase 3 trials over the 3–4-month treatment course were 5% with MDMA-AT and 17% in the placebo group (1–3).

Table 1. Published completed randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials of MDMA-AT for PTSDa

Figure 4. Pooled results from all phase 2 and 3 trials of MDMA-AT for PTSDa

a. Results pooled from all phase 2 and 3 clinical trials that used the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV or CAPS-5) as the primary outcome. Data are presented as mean and 95% confidence intervals. Adapted from published data (1–3, 86, 106, 108, 109, 119, 129, 153, 154).

Comparisons to current PTSD treatments.

Prolonged Exposure (PE) or Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) are trauma-focused psychotherapies that are widely accepted as the two gold-standard, first-line treatments for PTSD. Of individuals with military-related PTSD who receive PE and CPT, approximately one-third (28%–40%) of individuals no longer meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, 12%–20% of individuals achieve remission, and 13%–56% drop out of treatment (155, 156).

Currently available medications are less efficacious than trauma-focused psychotherapies for PTSD (157). The antidepressants sertraline and paroxetine are the only two medications approved by the FDA to treat PTSD. Yet, their low to moderate efficacy when used alone (158) has led them to be considered second-line treatments for PTSD (159). Their efficacy for PTSD further diminishes to being indistinguishable from placebo when combined with trauma-focused psychotherapy (160, 161). No studies have yet been conducted directly comparing MDMA-AT against other medications or psychotherapies. Further comparative studies are needed.

It is notable that the rates of loss of diagnosis and remission in the placebo-assisted therapy arms of MDMA-AT studies are comparable to those found in the active arms of studies of PE and CPT. This is potentially due in part to the extensive clinical contact associated with the MDMA-AT protocol—approximately 42 hours with two therapists. In contrast, PE and CPT involve approximately 12–18 hours of clinical contact with one therapist. Thus, this limits any direct comparisons that can be made between outcomes from studies of MDMA-AT versus those of other trauma-focused therapies.

Comorbid depression and insomnia.

Depression (162–165) and insomnia (166–169) are highly comorbid with PTSD, with each being prevalent in approximately 50% of cases of PTSD. They also potentially interact with PTSD to worsen its severity (170) and increase the risk of suicidality (171). MDMA-AT has been found to significantly improve symptoms of both comorbid depression (2) and insomnia (172) by treatment endpoint in individuals with PTSD. Improvements in insomnia continue to significantly improve between treatment endpoint and 12-month follow-up (172).

Posttraumatic growth.

Posttraumatic growth—a composite of post-trauma positive changes that can occur in self-perception, interpersonal relationships, and life philosophy—was measured by the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) across three of the MDMA-AT studies (total N=60) (173). Posttraumatic growth significantly increased after completing a course of MDMA-AT for PTSD (173). The magnitude of posttraumatic growth was sustained at 12-month follow-up (173). Similar to how posttraumatic growth has been associated with improvements in PTSD severity after PE (174), posttraumatic growth was associated with improvements in PTSD severity after MDMA-AT as well, which may in part explain the therapeutic mechanism of MDMA-AT (173).

Personality.

MDMA-AT may also promote increases in the personality structure of openness on the NEO Personality Inventory, with openness increasing from pre- to posttreatment relative to placebo for those with PTSD (175). Similar findings of increased openness have been described in studies of psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression (176, 177).

The relationship between PTSD, its treatments, and the personality domain of openness has not been well-described in the literature. However, low openness is a risk factor for treatment-resistant depression (178). MDMA-AT significantly improves openness in those with PTSD, and improvements in openness were further found to moderate improvements in PTSD severity, albeit in the context of a very small, underpowered sample (175). This suggests the possibility of increased openness being one potential mechanism by which MDMA-AT exerts its therapeutic effects for those with PTSD.

Other studies of MDMA-AT for PTSD.

Several additional single arm, nonrandomized, open-label studies of MDMA-AT for PTSD have been conducted as well (179). One such study involved using MDMA to enhance Cognitive Behavioral Conjoint Therapy (CBCT), which is a couples-based, empirically supported cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD. In this study, CBCT was modified by having the participant with PTSD as well as their significant other both jointly consume MDMA in two separate administration sessions spread out over the course of CBCT manualized treatment sessions (107). The underlying concept of this approach is that the prosocial effects of the MDMA may contribute to an added clinical benefit in the context of a key social relationship within the framework of couples-based therapy. MDMA-assisted CBCT was found to have large within-group effect sizes of PTSD symptom reduction comparable to traditional MDMA-AT (107), although further randomized placebo-controlled studies are needed.

MDMA-AT for Other Conditions

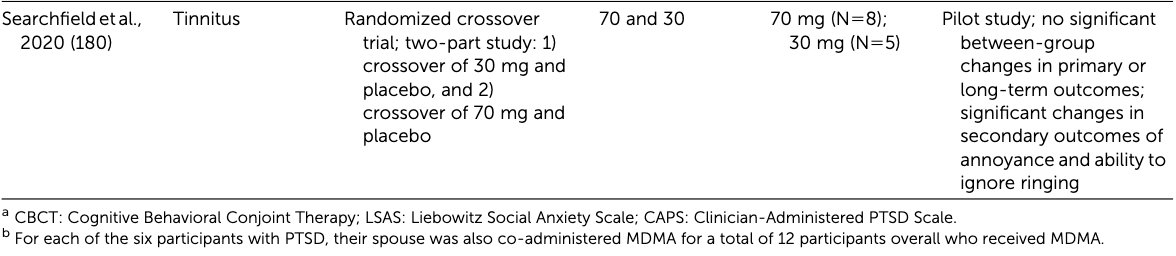

Recent clinical trials of MDMA-AT for conditions other than PTSD include single studies for alcohol use disorder (110), social anxiety in adults with autism spectrum disorder (105), anxiety related to life-threatening illness (111), and tinnitus (180). Despite their limitations, results from these non-PTSD studies suggest further study of MDMA-AT is warranted not only in PTSD but also in other conditions.

Alcohol use disorder.

The Bristol Imperial MDMA in Alcoholism Study (BIMA) is the first study of MDMA-AT for a substance use disorder. Fourteen individuals with alcohol use disorder who recently detoxed from alcohol received two sessions of open-label MDMA-AT with an initial dose of 125 mg of MDMA and a supplemental half dose 2 hours later. The open-label MDMA-AT group was compared with a separately conducted observational study of a similar population of 14 different individuals who received treatment as usual. Nine months post-detox, 75% of the observational group were drinking >14 units of alcohol weekly, whereas 21% of the MDMA-AT group met the same criteria (110).

Anxiety.

A small double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial (RCT) of MDMA-AT to treat social anxiety in 12 adults with autism spectrum disorder found that social anxiety significantly improved after two MDMA-AT sessions of 75–125 mg (plus a supplemental half dose 2 hours later) of MDMA (N=7) compared to inactive placebo (N=4) (105). Another RCT investigated two sessions of MDMA-AT for 18 individuals with anxiety or psychological distress related to a life-threatening illness comparing 125 mg (plus a supplemental half-dose 2 hours later) of MDMA (N=13) and inactive placebo (N=5) (111). Reductions in anxiety between arms were not statistically significant (p=0.056) (111).

Tinnitus.

A pilot within-group crossover RCT studying MDMA for tinnitus evaluated 70 mg of MDMA with inactive placebo crossover (N=8) versus 30 mg of MDMA with inactive placebo crossover (N=5). No differences were found in the primary outcomes of short-term tinnitus symptom severity and long-term tinnitus-related quality of life in this underpowered study (180). This study also did not offer participants a supplemental half dose as is typically done in studies of MDMA-AT, and a dose of 70 mg as the primary arm was the lowest dose used of any MDMA-AT study.

Limitations

Studies of MDMA-AT and psychedelics are generally characterized by several limitations including inadequate blinding, expectancy bias, lack of comparative studies, small numbers of participants, and highly selected populations (181). Studies of MDMA-AT also lack a robust body of dose-finding studies and long-term follow-up data.

Inadequate blinding is an inherent limitation for studies not only of MDMA-AT but also of psychedelics overall. Guessing of blinding was reported in five studies of MDMA-AT for PTSD (3, 86, 106, 108, 109), and the rest of the PTSD studies did not either assess or report success of blinding. Reported rates of correct guesses ranged from a reported 59% overall when combining both participants and therapists (108) to 95% for participants and 100% for therapists (106). Future studies may need to consider an active comparator such as methylphenidate or an amphetamine derivative.

Expectancy bias is another inherent limitation for studies of MDMA-AT and other psychedelics. Among 83 participants across all of the phase 2 studies of MDMA-AT for PTSD, nearly 10% (N=8) had used Ecstasy prior to their enrollment in the study (129). Prior lifetime use of MDMA was reported in 32% of participants in the first phase 3 trial (2) and in 46% of participants in the second phase 3 trial (3). This is problematic because these participants likely enter the study with higher expectations of a positive subjective experience or therapeutic benefit, which may bias the results in favor of a positive treatment effect (181). Prior MDMA experience is also problematic from the perspective of enacting a successful blind in studies with an active comparator condition.

Studies have not yet been conducted that directly compare MDMA-AT and another first-line treatment for PTSD. This has been due in part to the inherent challenges of designing a study that would adequately compare MDMA-AT and a first-line trauma-focused psychotherapy.

The relatively small number of patients across all phase 2 and 3 trials of MDMA-AT for PTSD (approximately 300) is relatively low compared with studies of other pharmaceuticals seeking FDA approval, which typically require thousands of patients. The low number of patients is justified in terms of statistical power to demonstrate a significant difference between treatment groups, due to the large effect size of MDMA-AT for the treatment of PTSD symptoms. However, it is questionable whether data from approximately 300 patients can adequately answer questions of safety or generalizability to a broad segment of the population. The limited patient data may not reliably characterize the full spectrum of potential adverse effects, especially adverse effects that are rare. However, nearly 2,000 individuals have received MDMA in clinical trials both including and aside from the treatment of PTSD (76), and more patients are continuing to receive MDMA-AT through Expanded Access treatment protocols, all of which will contribute to safety data. Altogether, this emphasizes the critical importance of phase 4 post-market monitoring of MDMA-AT.

Despite the relatively small numbers of participants enrolled in studies of MDMA-AT, these studies attract and screen large numbers of individuals seeking enrollment, with only approximately 10% of screened individuals being enrolled. This allows the study to be highly selective about enrolling participants, which consequently limits generalizability. Certain patient populations such as those with borderline personality disorder, substance use disorders, and history of psychosis are also excluded from studies, thus further reducing the generalizability of results.

The current body of MDMA-AT clinical trials lacks adequate dose-finding studies. The active arm of all phase 2 and 3 studies conducted thus far have used either 120 mg or 125 mg as the highest initial dose of an MDMA session (followed by a 60–62.5 mg supplemental half dose 90–120 minutes later, for a total cumulative dose of 180–187.5 mg per dosing day) (1–3). No studies evaluated initial doses higher than 125 mg, and only two studies introduced a third arm with an intermediate doses of either 75 mg (N=7) (86) or 100 mg (N=9) (109). Although there were no differences between the 100-mg and 125-mg arms compared with the 40-mg control arm in Ot’alora et al. (109), the 75-mg arm in Mithoefer et al. appeared to have a greater effect size (loss of diagnosis, N=6 of 7 [86%]; between-group Cohen’s d=2.8) than the 125-mg arm (loss of diagnosis, N=7 of 12 [58%]; between-group Cohen’s d=1.1) compared with the 30-mg control arm (loss of diagnosis, N=2 of 7 [29%]) (86). Despite this unanticipated potential signal of an intermediate dose effect, further well-powered dose-finding studies were not pursued. Such studies are still needed.

The questions of a potential intermediate dose effect, dose preference, and need for supplemental dose were partially addressed in the phase 3 studies. All participants were started at an initial dose of 80 mg (plus a supplemental half dose 90–120 minutes later) for their first session. Based on tolerability and shared decision-making, the protocols allowed for flexibility in the second and third MDMA sessions to either increase the initial dose to 120 mg (with or without a supplemental half dose) or stay at an initial dose of 80 mg (with or without a supplemental half dose) (2, 3). With a few exceptions, nearly all participants elected to take the 120-mg initial dose with a supplemental half dose for each of their last two MDMA sessions (2, 3). Thus, current evidence does not allow for differentiating safety and efficacy profiles between treatment courses where the second and third MDMA sessions utilize 1) initial doses of 80 mg versus 120 mg or 2) dosing with versus without supplemental half doses.

Although long-term follow-up data at 1 and 4 years suggests the treatment effect of MDMA-AT for PTSD is durable (129, 153), no blinded, placebo-controlled data exist beyond 2 months after the final dosing session. All phase 2 and 3 participants were unblinded after the primary outcome measure 1–2 months after their final dosing session, and those who received placebo were offered to crossover to open-label MDMA-AT. One-third to nearly half of participants who received placebo no longer met criteria for PTSD after a course of treatment (2, 3), and PTSD is known to gradually improve in many individuals even without treatment (164). Thus, without blinded, placebo-controlled long-term follow-up data, reliable conclusions cannot yet be drawn about the long-term durability and magnitude of treatment effects.

Future Directions

Pharmacology: MDMA Derivatives and Analogs

Altering the pharmacology of the psychedelic by developing derivatives and analogs is an avenue with wide potential for further research. MDMA is comprised of a racemic mixture of S(+)-MDMA and R(−)-MDMA. Compared to the racemic mixture of traditional MDMA, the enantiomer R(−)-MDMA potentially has an improved therapeutic index and reduced side effect profile (182) while still maintaining its prosocial effects (183). R(−)-MDMA is currently being developed as a potential therapeutic for autism spectrum disorder (184). Several other MDMA derivatives are also being developed (185–187).

Lysine-MDMA and lysine-MDA are derivatives of MDMA and MDA, respectively, currently undergoing their first human clinical trial in healthy subjects (187). Similar to the FDA-approved medication lisdexamfetamine—which attaches the amino acid lysine to dextroamphetamine to create a prodrug with a more gradual onset of action—lysine is being similarly attached to MDMA and MDA to potentially achieve a similar effect. Especially given the long durations of action of MDMA and other current psychedelics, further studies are needed to examine the pharmacology of not only currently established psychedelics but also their derivatives and analogs.

Investigating Therapeutic Mechanisms

While clinical efficacy continues to be established for MDMA-AT, the precise neurobiological mechanisms underlying its efficacy are still unclear. Although MDMA seems to facilitate memory reconsolidation and fear extinction (26, 50, 51), this research is nascent, and further studies are needed to clarify the biological, psychological, and social mechanisms by which this occurs.

MDMA-mediated endogenous release of oxytocin has been implicated potentially as a central component of MDMA’s therapeutic mechanism due to its ability to reopen a critical period of social reward learning in rodent models (43). Although these findings have yet to be corroborated in humans, the capacity to reopen critical periods of social reward learning in rodents has been replicated with other classical and nonclassical psychedelic compounds with varying mechanisms of action (ketamine, psilocybin, LSD, and ibogaine) and which lack MDMA’s unique prosocial effects (188). These findings shift our thinking away from the importance of MDMA-mediated oxytocin release specifically reopening windows of social reward learning. They instead shift our focus toward a more overarching concept of psychedelics as a “master key” for activating a common pathway of reopening critical periods of metaplasticity (defined as “a change in the ability to induce subsequent synaptic plasticity, such as long-term potentiation or depression”) by regulating DNA transcription of components, receptors, and proteases associated with the extracellular matrix (188). The widened window of tolerance (189) to stress and fear (46) that is observed in MDMA-AT also warrants further study in humans.

While MDMA may lead to substantial increases in neuroplasticity in the form of neuritogenesis and synaptogenesis (68), further studies are needed to better understand the neurobiological underpinnings of these changes and their clinical implications, particularly in those with traumatic brain injury and other trauma-related conditions.

MDMA-AT promotes improvements in posttraumatic growth (173) as well as in the personality domain of openness (175)—each of which may contribute to an overall framework describing its therapeutic mechanism. However, much is still unclear as to what extent these and other psychological factors contribute to the therapeutic efficacy of MDMA-AT.

Therapeutic alliance and rapport have been implicated as potential moderators of treatment response to psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression (190). However, therapeutic alliance and rapport have yet to be studied as moderators of treatment response in MDMA-AT.

Examining and Developing the Therapeutic Modality

As described earlier, MDMA-AT utilizes a manualized yet open-ended modality that incorporates a nondirective, person-centered approach. Many components of this modality are grounded in approaches established by the initial generation of Western psychedelic therapists and refined over time (191). While randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials have thus far studied the medication (MDMA versus placebo) as the variable, no trials have yet studied the therapeutic modality itself versus a control therapeutic modality as the study variable. Component analyses to study various components of the MDMA-AT therapeutic modality are also warranted.

The first study using MDMA to enhance a traditional psychotherapeutic modality was conducted with a single-arm study of MDMA-Assisted Cognitive Behavioral Conjoint Therapy for PTSD where both the patient and their spouse received MDMA together (107). Similar studies will be needed to study other current first-line psychotherapeutic modalities augmented by MDMA and whether the augmentation of an evidence-based psychotherapeutic approach with MDMA produces superior outcomes to MDMA-AT in the standard model.

Novel Indications

Clinical trials have studied MDMA-AT for PTSD, alcohol use disorder, anxiety disorders, and tinnitus (Table 2). Studies are also being planned for eating disorders, traumatic brain injury (193), and female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (194). By far, the largest evidence base lies in MDMA-AT for PTSD, with other conditions having only small—often uncontrolled—clinical trials currently published. Further studies are needed to examine MDMA-AT for a wider range of psychiatric conditions.

Table 2. Other clinical trials of MDMA-ATa

Table 2 (Continued).

Care Delivery Models and Resource Intensiveness

Accounting for two to three MDMA sessions, MDMA-AT in its current form is a highly resource-intensive treatment with approximately 26–42 therapist-hours needed for each of the two therapists for a total of approximately 52–84 therapist-hours to complete a course of treatment. In contrast, current manualized first-line trauma-focused psychotherapies such as PE and CPT typically involve 8–15 sessions anywhere between daily to weekly with one therapist and 60–90 minutes per session for a total of 8–23 therapist-hours over a single course of treatment (195). Nevertheless, MDMA-AT compared to standard of care has been suggested to be cost-effective, generating health care savings of $132.9 million over 30 years and averting 61.4 premature deaths for every 1,000 patients (196, 197).

The following are 10 potential avenues of future research to improve the efficiency of care delivery for MDMA-AT and other psychedelic-assisted therapies. Each of these potential avenues of research represents a departure from the current established care delivery model of having two co-therapists in the room with the patient for every preparation, medication, and integration session that was established to maximize safety and efficacy. It is yet unclear if any of these approaches can indeed maintain safety and efficacy while improving resource efficiency. However, they are mentioned here for researchers to consider.

1.Simultaneous administration whereby multiple rooms are run simultaneously with a single facilitator per room while the supervising facilitator is in a video control room concurrently supervising all rooms. For example, if five rooms are running at once with one patient each, this would require a total of six facilitators instead of 10.2.Group administration of the medication in a single large room with several facilitators supervising. This is already being done in Switzerland in groups of up to 12 patients (198).3.Group preparation and/or integration sessions, or a combination of individual/group preparation and/or integration sessions.4.A combination of simultaneous administration and group administration over a course of treatment.5.Having the patient’s primary therapist be the second facilitator.6.Having a single facilitator per patient.7.Having facilitators primarily not in the room with the patient.8.Having some of the preparation be done with pre-recorded video modules.9.Further limiting the number or length of preparation and/or integration sessions.10.Utilizing telehealth for some of the preparation and/or integration sessions.

Public Policy and Access for Nonmedical Use

Another important consideration is the dichotomy between medical use and nonmedical use. Although the national conversation has primarily been focused on medical use, there are growing efforts to legalize or decriminalize nonmedical use of psychedelics, with various models being proposed that mental health professionals must be aware of to better appreciate the rapidly evolving landscape of psychedelic public policy.

One model already passed into law is the Oregon Model, which passed as Ballot Measure 109 in November 2020. As of 2023, nonmedical facilitators may be licensed by the state of Oregon to administer psilocybin to individuals for nonmedical use (199). The rationale to receive psilocybin under the Oregon Model is not to treat a medical diagnosis but rather to improve well-being and quality of life (operationalized as “psilocybin services”), which in turn may lead to greater public access to psilocybin compared with the medical model (200). Although the Oregon Model is specific to psilocybin, it is plausible that this model may encompass MDMA and other psychedelics if it is passed into law in other states. While the nonmedical model poses numerous concerns and risks that must be mitigated, it is a potential reality that clinicians must contend with in the future and must be equipped with knowledge of appropriate safeguards.

Another model is the decriminalization of possessing, obtaining, sharing, and personally using psychedelics (200). California Senate bill 519 proposes this model for MDMA and several other psychedelics. Although it has not yet been passed as of the time of writing, its passage would make California the first state to legalize this model. However, this model has already been adopted by smaller localities in Denver, Colorado; Oakland, California; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

A third model that is an intermediate between the Oregon and California models that adds an additional layer of safeguards to mitigate unsafe use: licensed personal use. In this model, individuals would be licensed by the state to acquire and personally use a pharmaceutical-grade psychedelic within predetermined limitations of amount, frequency, and/or pattern of use set by state law. Much like with driving a vehicle, the license would be revoked after meeting a legal threshold of irresponsible use. This model has not yet been adopted by any jurisdiction.