Abstract

Background Positive and negative alcohol expectancies (PAEs and NAEs, respectively) and impulsivity are key risk factors for the onset of alcohol use. While both factors independently contribute to alcohol initiation, the developmental aspects of AEs and their nuanced relationship with impulsivity are not adequately understood. Understanding these relationships is imperative for developing targeted interventions to prevent or delay alcohol use onset in youth.

Methods This study utilized the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development cohort to examine how PAEs and NAEs develop over time and relate to each other. We also explored how self-reported and behavioral impulsivity at baseline (~10 years old) are associated with the longitudinal development of PAEs and NAEs in youth Ages 11, 12, and 13 (n = 7493; 7500; and 6981, respectively), as well as their time-specific relationships.

Results Findings revealed while PAEs increased steadily over all three years, NAEs increased from ages 11–12 and then remained unchanged between 12 and 13. Overall, PAEs and NAEs were inversely related. Moreover, PAEs positively correlated with sensation seeking and lack of premeditation, while NAEs negatively correlated with positive urgency. Interestingly, a time-specific association was observed with PAEs and lack of perseverance, with a stronger correlation to PAEs at Age 11 compared to Age 12.

Conclusions Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the divergent developmental trajectory of PAEs and NAEs, and their overall and time-specific associations with impulsivity. These findings may guide focused and time-sensitive prevention and intervention initiatives, aiming to modify AEs and reduce underage drinking.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a pivotal phase of physical, neurobiological, and cognitive development (Casey et al., 2008), coupled with increased novelty-seeking behaviors such as alcohol experimentation (Fraga et al., 2011). While initial experimentation may start with normative drinking patterns (i.e., sipping or tasting or first drink of alcohol), the risk of progressing to hazardous alcohol use, such as binge drinking, and alcohol dependence, tends to amplify with age (Aiken et al., 2018). To understand this potential risk, it is essential to recognize how antecedent precursors, such as an individual's beliefs about the consequences of drinking (i.e., alcohol expectancies) (Mann et al., 1987) and impulsive behaviors (Chalmers and Stein, 1993, Colder and Chassin, 1997) may contribute alcohol initiation and escalation.

Alcohol expectancies (AEs) represent the beliefs about the behavioral, physiological, and cognitive consequences of alcohol-related experiences, encompassing both positive beliefs such as increased socialization, relaxation, and tension reduction (i.e., positive AEs; PAEs) and negative beliefs such as poor behavioral control, risk-taking behaviors, and poor decision-making (i.e., negative AEs; NAEs)(Mann et al., 1987). PAEs are shown to be significantly associated with frequent and problematic alcohol use (Mann et al., 1987), whereas, NAEs are associated with lower levels of drinking (Cho et al., 2019), although the literature on the association between NAEs and alcohol use has yielded mixed results (McMahon et al., 1994, Ramirez et al., 2020). Ongoing investigation into the developmental trajectory of PAEs and NAEs is essential for a more precise understanding of their association with alcohol use.

Prior studies emphasize that environmental influences, like parental alcohol behavior, peer interactions, and media, initially shape the perceptions of alcohol, leading children to hold predominantly NAEs (Smit et al., 2018). Typically, during grades 4–6, AEs tend to shift towards more PAEs while NAEs decrease suggesting an inverse correlation between PAEs and NAEs (Bekman et al., 2011). In fact, studies propose this shift from higher NAEs to higher PAEs as a critical period, as it may play a causal role in earlier alcohol use in adolescents (Copeland et al., 2014, Miller et al., 1990). Alternatively, the ambivalence model of alcohol use (Breiner et al., 1999) proposes a simultaneous interplay between both approach and avoidance tendencies towards alcohol, highlighting the complexity of this relationship (Cameron et al., 2003, Scheffels et al., 2023). Thus, the relationship between PAEs and NAEs and the evolution of this relationship during adolescence are poorly understood, especially during the critical period of AEs development in alcohol-naïve youth. Understanding these relationships is crucial given the development of these alcohol-related cognitions are not only associated with alcohol use onset, but also its maintenance, and even problematic use.

AE predict the onset of alcohol use and mediate the influence of dispositional factors (i.e., impulsivity) on drinking behaviors (Corbin et al., 2011, Peterson et al., 2018). Impulsivity, a known risk factor for adolescent alcohol use, involves stable personality tendencies (commonly termed as traits) such as premature decision making, insensitivity to consequences, and seeking novel experiences, along with impulsive action (i.e., failure to inhibit prepotent responses), and choice (i.e., preference for small, immediate rewards over larger, delayed ones) (Halvorson et al., 2021, Watts et al., 2020). Assessing these dimensions includes the use of self-report questionnaires [e.g., the UPPS-P [Negative Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, Positive Urgency] Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside and Lynam, 1999)], and behavioral approaches, with the Stop Signal Task used for measuring impulsive action, and the Delayed Discounting Task (DDT) or Cash Choice Task (CCT) used for measuring impulsive choice (MacKillop et al., 2016). Although, self-report and behavioral assessments of impulsivity have shown to evaluate similar underlying constructs related to poor inhibitory control, there is notable variability and often limited overlap between these facets of impulsivity (Cyders and Coskunpinar, 2011, Meda et al., 2009, Reynolds et al., 2007). A few studies have explored the relationship between different facets of impulsivity and AEs (Colder and Chassin, 1997, Settles et al., 2010, Wiers et al., 2006); however, these have predominantly focused on impulsive personality tendencies, thus not capturing impulsivity comprehensively. For example, research shows that youth with higher sensation seeking and lack of premeditation tend to have stronger PAEs, leading to increased alcohol consumption (Banks and Zapolski, 2017, Scott and Corbin, 2014), while the impact of negative urgency on drinking is linked to both PAEs and NAEs (Anthenien et al., 2017). Despite limited evidence linking behavioral impulsivity and AEs, a previous study demonstrated that motor impulsiveness, assessed by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and correlated with SSRT (Enticott et al., 2006, Logan et al., 1984), is associated with alcohol consumption, and is mediated by PAEs (Barnow et al., 2004). Furthermore, another study observed that steeper delay discounting assessed via DDT was associated with stronger PAEs (particularly sexual enhancement) (Celio et al., 2016). While not directly examined in alcohol naïve youth, these findings indicate potential links between behavioral impulsivity and AEs. Moreover, existing studies to date insufficiently represent early adolescence (often exploring youth beyond age 11), alcohol-naïve youth, and have inadequate sample sizes (often fewer than 600 participants), thereby hindering the generalizability of findings.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the development of AEs in alcohol naïve youth from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study — a cohort of 11,000 youth across the United States. This investigation spans from baseline self-report and behavioral impulsivity to AEs at ages 11, 12, and 13 employing a robust longitudinal design with data collected over four years. We expected an increase in PAEs and a gradual decline in NAEs with age, particularly given transitions into adolescence. We investigated relationships between PAEs and NAEs at different time points, anticipating a negative correlation between PAEs and NAEs. Lastly, we investigated relationships between self-reported and behavioral impulsivity at baseline and in relation to the longitudinal development of PAEs and NAEs. We hypothesized self-reported impulsivity would associate with developmental increases in PAEs. Due to limited prior research, we did not have specific hypotheses for behavioral impulsivity nor for associations with NAEs.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of sample

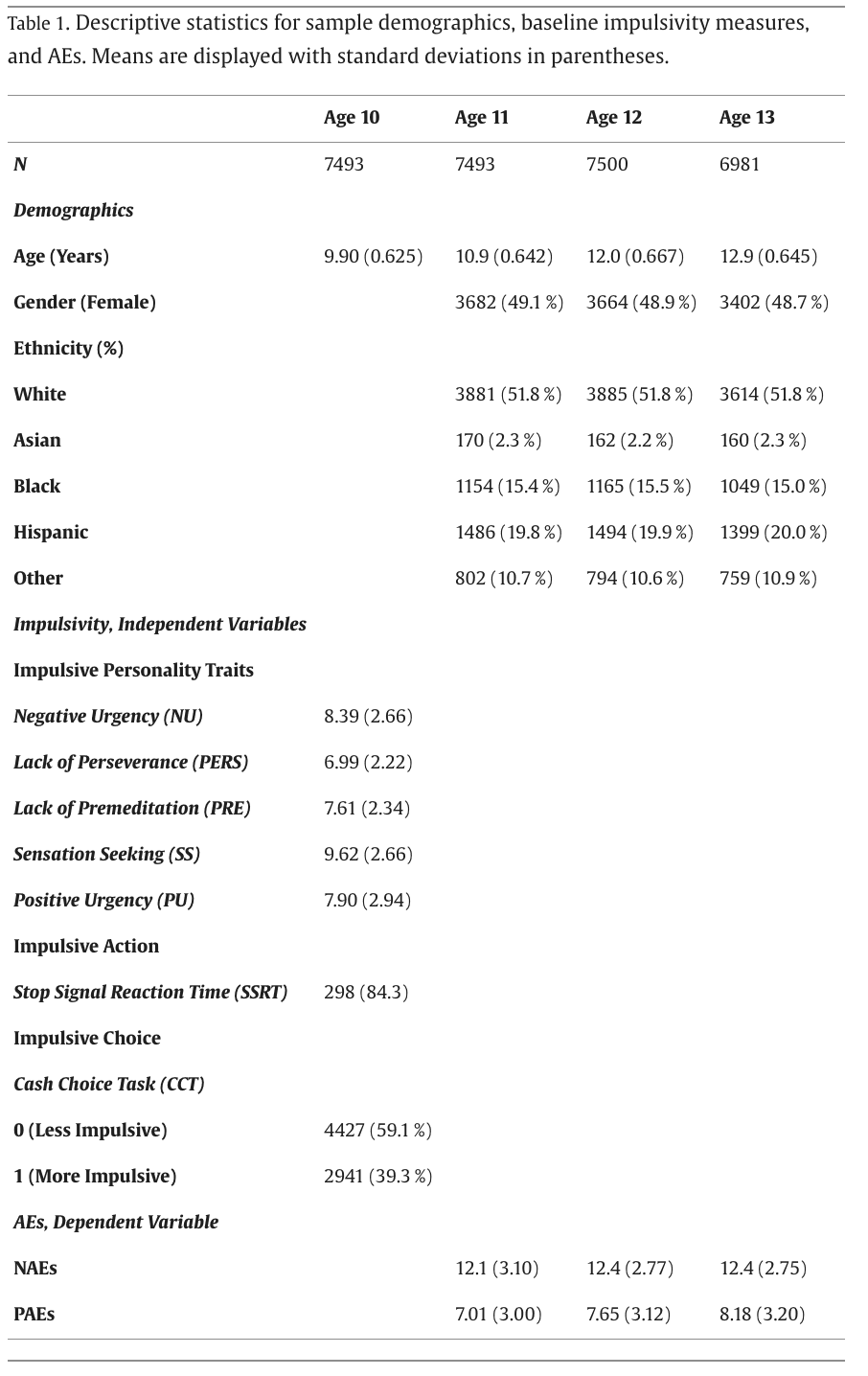

In this study, we analyzed longitudinal changes in PAEs and NAEs between Years 1 (ages 10–11), 2 (ages 11–12), and 3 (ages 12–13) in alcohol-naïve youth while accounting for demographic covariates, and other potential confounders. We included participants with complete data on sociodemographic factors (i.e., age, gender, race, family income and parental education), psychopathology (i.e., internalizing, and externalizing symptoms), and family history of alcohol misuse from the ABCD cohort (release 5.0). Informed consent was obtained from all participating youth and parents (Uban et al., 2018). Since alcohol use influences both PAEs and NAEs (Bekman et al., 2011), and our aim was to ascertain these relationships in alcohol-naive youth, we removed all youth who had initiated alcohol use from our analyses and only explored alcohol-naïve youth (see Supplement; Inclusion Criteria (Fig. S1)). The final participant sample size was 7493 (Year 1), 7500 (Year 2) and 6981 (Year 3). Moreover, we used self-report (i.e., UPPS-P) and behavioral (i.e., impulsive choice, impulsive action) impulsivity measures at baseline (9–10 years old) to test whether impulsivity at baseline statistically predicted PAEs and NAEs at Years 1, 2, and 3. For simplicity, we represented the four annual assessments using participants’ average ages; Age 10 for baseline, Age 11for year 1, Age 12 for year 2 and Age 13 for year 3 (see Table 1).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Alcohol expectancies

The ABCD study assessed alcohol expectancies via the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire-Adolescent, Brief (Stein et al., 2007), a 7 point Likert scale (1 = Disagree Strongly, 5 = Agree Strongly) to evaluate adolescent’s beliefs about perceived drinking outcomes. The AEQ-AB includes seven items reflecting both positive (PAEs, e.g., alcohol makes a person relax) and negative (NAEs, e.g., alcohol makes a person mean to others) expectations about the effects of alcohol. Responses to each item were summed to create a subscale score for PAEs and NAEs, resulting in separate PAEs at Age 11 (internal consistency: Cronbach’s α = 0.68), Age 12 (α = 0.70), and Age 13 (α = 0.71), as well as NAEs at Age 11(α = 0.69), Age 12 (α = 0.70) and Age 13 (α = 0.74). Cronbach’s alpha between 0.6 and 0.8 is deemed acceptable (Shi et al., 2012). It is important to note that AEQ-AB available assessments at the time of study were up to Age 13, and AEQ-AB was not assessed at Age 10. Additional AE details are provided in Supplement (Table S1 and Figures S2-S5).

2.2.2. Alcohol sipping

Alcohol exposure was assessed using the iSay Sip Inventory (Jackson et al., 2015). Youth were asked “…Have you ever tried a sip of alcohol at any time in your life?” To ensure we were only assessing alcohol naive youth, we excluded children who responded “yes” at all times points. The removal of youth who endorsed sipping, also ensured that there were no youth who endorsed having more than a sip of alcohol.

2.2.3. Self-reported impulsivity

2.2.3.1. UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale (UPPS-P)

The Children-Short Form UPPS-P (Watts et al., 2020) is an abbreviated 20-item measure that assesses Negative Urgency (NU) - acting rashly in response to negative affect (α = 0.64); Positive Urgency (PU) - acting rashly in response to positive affect (α = 0.78); Sensation Seeking (SS) - seeking new and thrilling activities (α = 0.48); (lack) of Premeditation (PRE) - acting without considering potential consequences (α = 0.73); and (lack) of Perseverance (PERS) - quitting when something becomes difficult (α = 0.69). See Supplement (Table S2) for individual items and the assessment of the internal reliability. Since SS had low internal reliability, we employed a sensitivity analysis by systematically removing SS items and recalculating Cronbach’s alpha. This technique did not yield any significant improvement in SS Cronbach’s alpha. See Supplemental Section for a detailed table.

2.2.4. Behavioral impulsivity

2.2.4.1. Impulsive action

Tendencies to inhibit prepotent responses were indexed by the Stop Signal Reaction Time (SSRT) from the Stop Signal Task (Luciana et al., 2018), which was performed during MRI scanning. The task consisted of serial presentations of leftward and rightward facing arrows, and participants were instructed to indicate the direction of the arrows using a two-button response box (the “go” signal), except when the left or right arrow was followed by an arrow pointing upward, (the “stop” signal). The SSRT (i.e., the duration required to inhibit a “go” response after a “stop signal” had been presented) indexes inhibitory speed, and is one of the most frequently employed metrics for tracking impulsive action (Wang et al., 2016).

2.2.4.2. Impulsive choice

Performance on the Cash Choice Task (CCT) reflects temporal discounting (Wulfert et al., 2002), and has relative concordance with the DDT in the ABCD study (Kohler et al., 2022). In CCT, participants are asked to decide between $75 dollars in 3 days or $115 in 3 months with a third option of ‘can't decide’. For our analyses, CCT was re-coded, such larger-later reward options were coded with a “0”, smaller-sooner reward choices were coded as “1”, and “don’t know” responses were excluded from analysis, as done previously (Guerrero et al., 2019). Though impulsive choice is commonly measured with the DDT, few studies have employed the CCT to track impulsive choice (Kohler et al., 2022, Sparks et al., 2014).

2.2.5. Covariates

Sociodemographic indices, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and parental history of alcohol misuse were included as covariates (see Supplement Section 2).

3. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (4.1.3). Code is available at https://github.com/faith-adams-mssm/impulsivityanalysesfeb2024 .

We employed covariate-adjusted linear mixed effect (LME) models using “lme4” package (Bates et al., 2015). These models were designed to examine the relationships between key explanatory variables (i.e., time and impulsivity) and dependent variables, namely PAEs and NAEs, We controlled for covariates: age, race, gender, family income, and internalizing, externalizing misuse, and parental history of alcohol misuse, while accounting for random effects of site, and family. To ensure the robustness of our models, we bootstrapped these models with 1000 iterations at a 95 % confidence interval using “lmersampler” package (Loy and Korobova, 2021). Confidence intervals and bootstrapped p-values were reported.

To investigate longitudinal changes in PAEs and NAEs while controlling for covariates, each LME model included time as the categorical independent variable, and PAEs or NAEs as continuous dependent variables. By comparing different time points, we aimed to gain insights into the influence of time on PAEs and NAEs and to understand any variations between Ages 11, 12 and 13 with respect to PAEs and NAEs. We conducted two sets of analyses here. The first set of analyses included all three time points, with Age 11 serving as the reference, allowing for comparisons between Age 11 and Age 12, as well as between Age 11 and Age 13. Subsequently, to examine the changes between 12 and 13, the second set of analyses only included these two time points, with Age 12 serving as the reference.

To investigate relationships between PAEs and NAEs, we employed Spearman Correlations (Zar, 1972). We examined the correlations between PAEs and NAEs, separately at Ages 11, 12 and 13 and used FDR correction to account for multiple comparisons. To investigate relationships between Age 10 impulsivity measures and PAEs and NAEs longitudinally, self-report and behavioral impulsivity measures were used as key independent variables, and PAEs or NAEs as dependent variables. These analyses also accounted for each time PAEs or NAEs were collected, by including an interaction term for time (Age 11, 12, and 13) with each impulsivity measure. This allowed us to explore the specific time-dependent variations in the relationships between individual impulsivity measures and PAEs or NAEs.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Across time, most of the descriptive variables and participant counts remained consistent at each subsequent follow-up. Upon examining participants’ characteristics, we found ~50 % of the participants were White, ~38 % came from higher income families earning more than $100,000 annually, 70 % had parents with higher educational attainment, and 82 % lived in households without a parent with an alcohol misuse (Table 1).

4.2. Longitudinal changes in PAEs and NAEs

4.2.1. PAEs

LME models revealed a significant age-related increase in PAEs, such that PAEs increased from age 11–12 (β = 0.633, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.545–0.716]), age 12–13 (β = 0.575, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.494–0.661]) and age 11–13 (β = 1.206, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [1.110–1.295]) (Table S3).

4.2.2. NAEs

LME models revealed NAE increased from ages 11–12 (β = 0.384, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.302–0.471]) and ages 11–13 (β = 0.353, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.264–0.442]); however, scores remained comparable from ages 12 and 13 (β =-0.031, pboot = 0.418, 95 % CI [-0.115–0.054]) (Table S3).

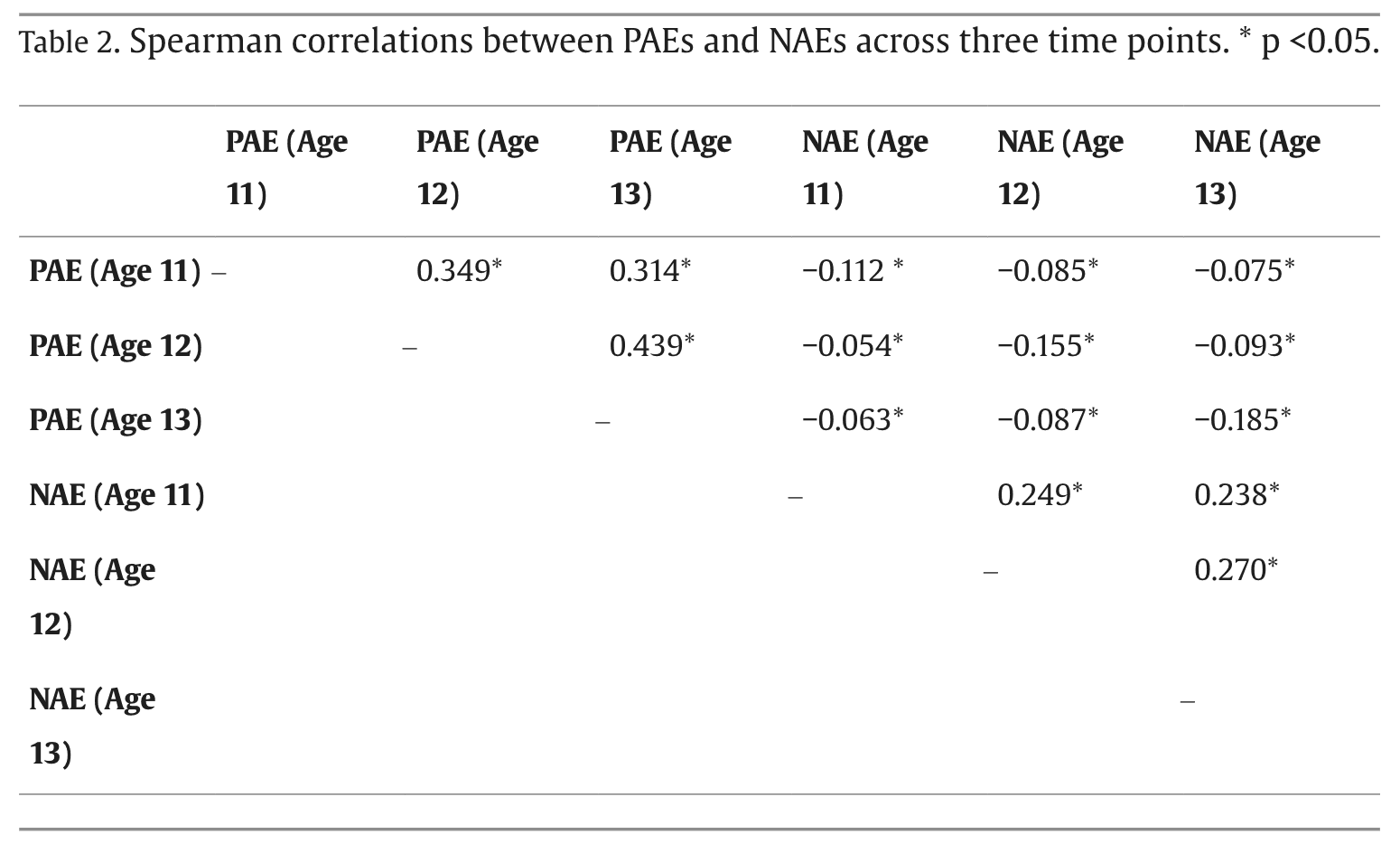

4.3. Correlations between PAEs and NAEs

We examined correlations between PAEs and NAEs at each age (Table 2). Expectedly, PAEs at Age 11 were positively correlated with PAEs at Ages 12 (r = 0.349, p < 0.001) and 13 (r = 0.314, p < 0.001), and PAEs at Age 12 were correlated with PAEs at Age 13 (r = 0.439, p <.001). Also expectedly, NAEs at Age 11 were positively correlated with NAEs at Ages 12 (r = 0.249, p < 0.001) and 13 (r = 0.238, p < 0.001), while NAEs at Age 12 were positively correlated with NAEs at Age 13 (r = 0.270, p < 0.001). Additionally, we found PAEs and NAEs were negatively correlated with each other throughout the years. PAEs at Age 11 were negatively correlated with NAEs at Age 11 (r = −0.112, p < 0.001), at Age 12 (r = −0.085, p < 0.001), and at Age 13 (-0.075 p < 0.001).

4.4. Associations between impulsivity at baseline and AEs

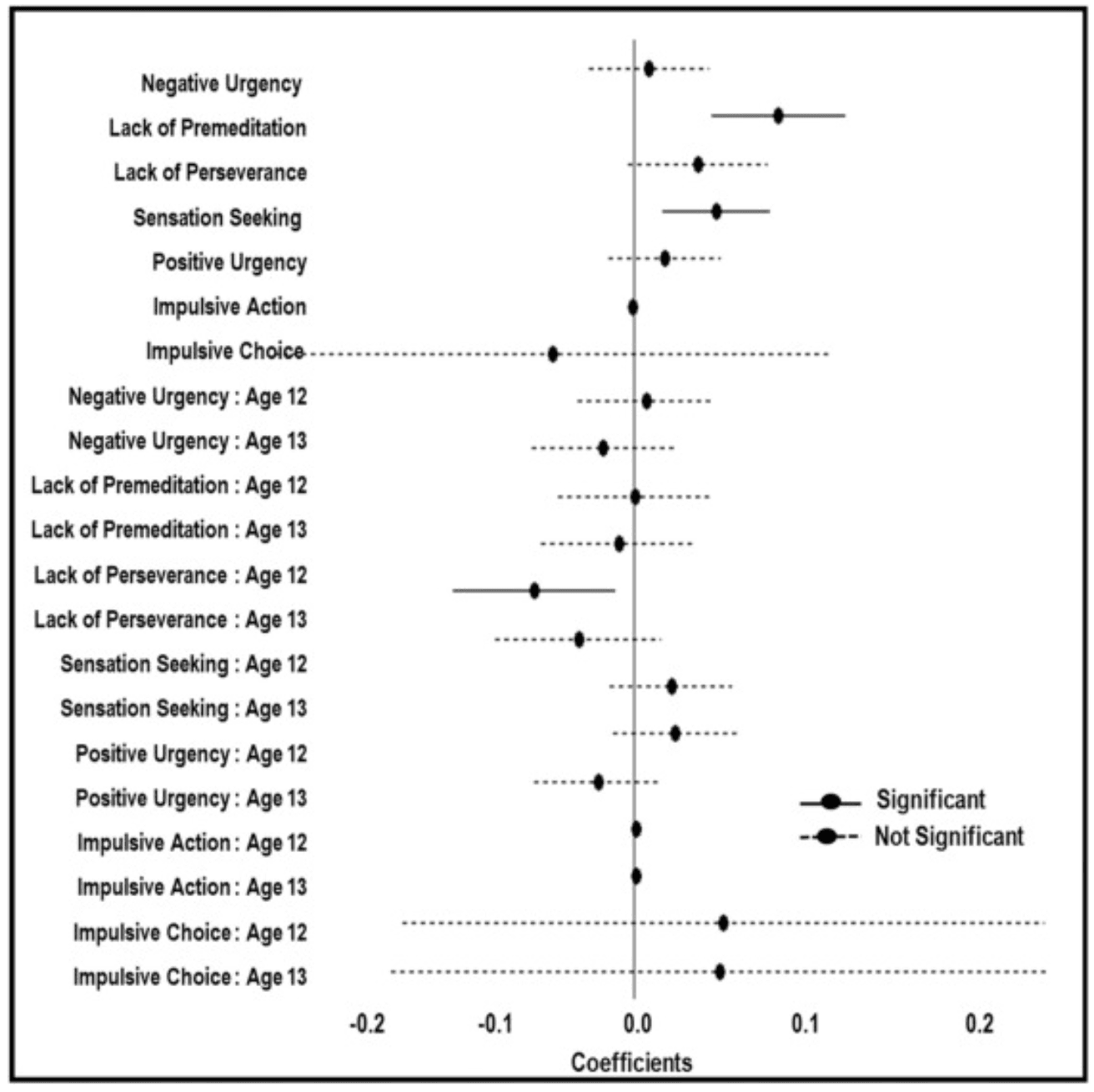

4.4.1. PAEs

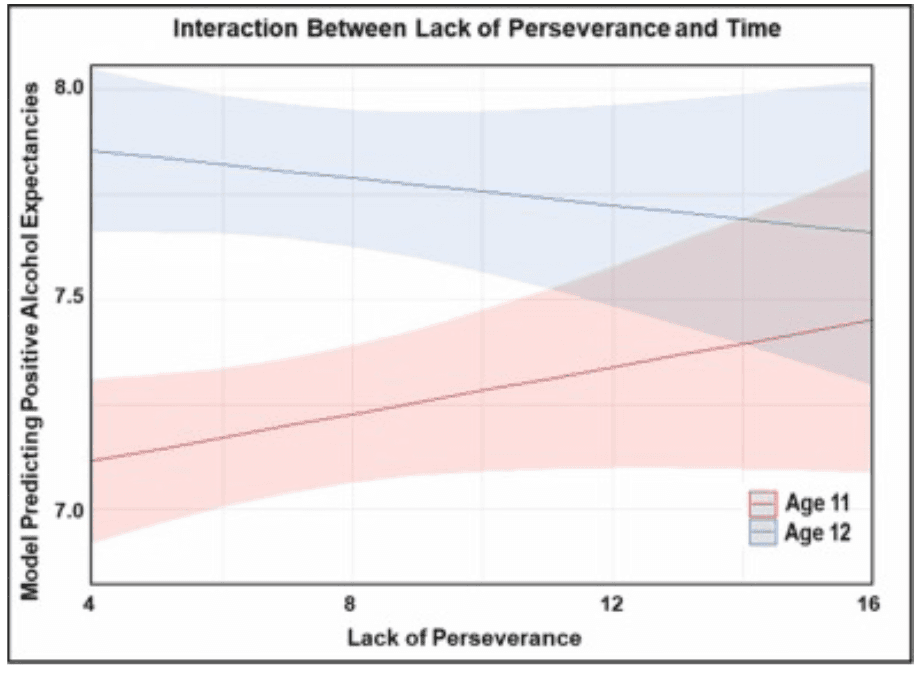

Results revealed that self-reported impulsive tendencies at Age 10 were significantly associated with stronger PAEs. Specifically, higher mean PAEs across all three years were associated with greater SS (β = 0.077, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.014–0.077]) and greater PRE (β = 0.116, pboot < 0.001, 95 % CI [0.045–0.116]) (Fig. 1 and Table S5). When exploring the temporal dynamics (impulsivity-by-time interaction), PERS was associated significantly more positively with PAEs at Age 11, compared to with PAEs at Age 12 (β = –0.009, pboot = 0.017, 95 % CI [-0.101 - −0.009]) (Fig. 2 and Table S5).

Fig. 1. The coefficient plot illustrates the estimate sizes for predictors of PAEs. Solid black lines indicate significant estimates (p < 0.05), while dashed lines represent non-significant estimates.

Fig. 2. Plot illustrating the interaction between PERS at Age 10 and PAEs at Ages 11 and 12.

4.4.2. NAEs

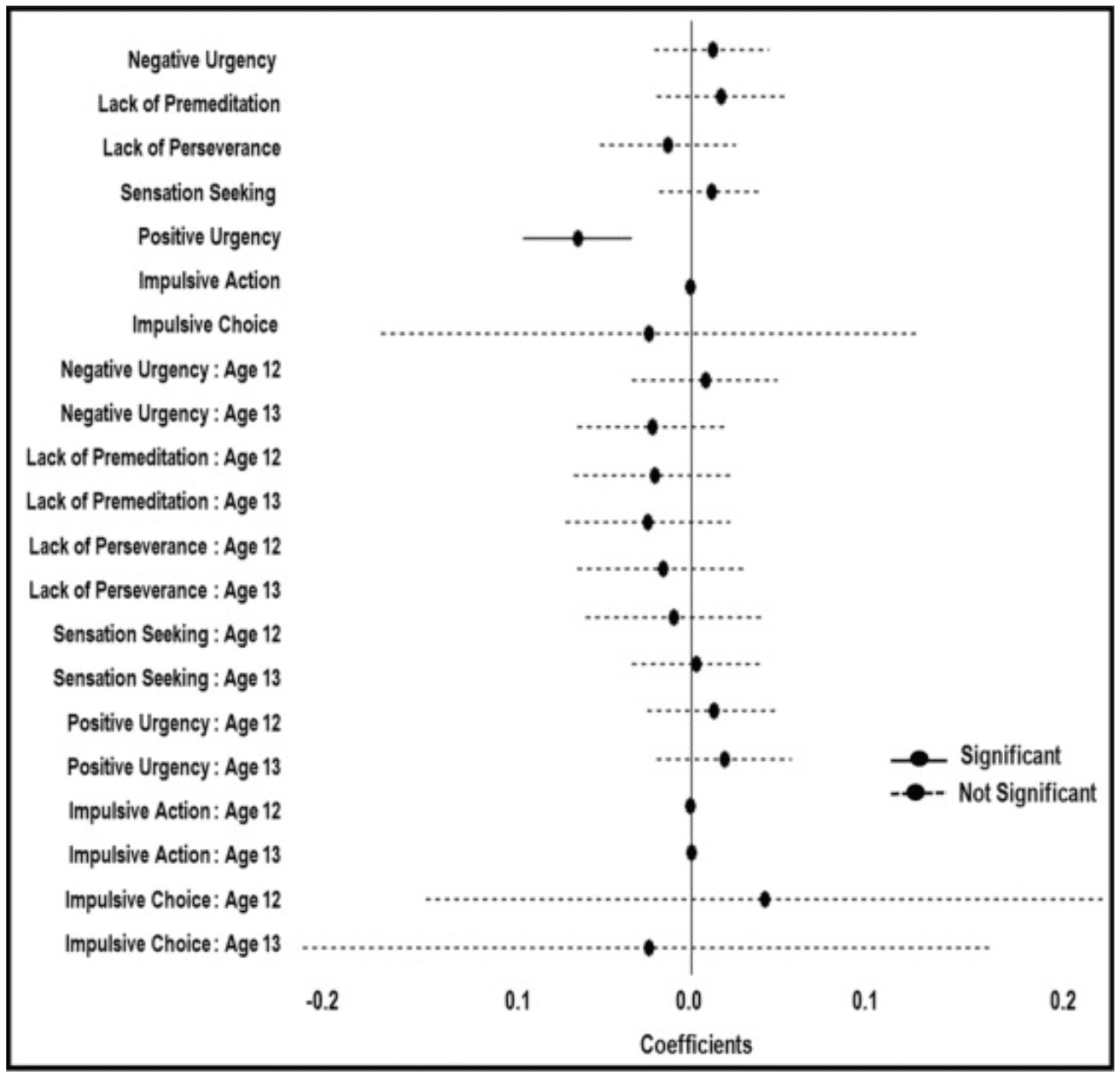

The models revealed higher positive urgency at Age 10 was associated with lower NAEs across all three years (β = −0.084, pboot = 0.004). No statistically significant impulsivity-by-time interactions were observed for PAE (Fig. 3 and Table S5).

Fig. 3. The coefficient plot illustrates the estimate sizes for predictors of NAEs. Solid black lines indicate significant estimates (p < 0.05), while dashed lines represent non-significant estimates.

5. Discussion

In this study, using ABCD data, we showed that PAEs gradually increased through ages 11–13, whereas NAEs increased from ages 11–12 and subsequently remained comparable between ages 12 and 13. We further showed that PAEs and NAEs were inversely correlated at each time point. For associations between different facets of impulsivity and AEs, we observed that PAEs were positively correlated with SS and PRE, and NAEs were negatively correlated with PU. Interestingly, we observed a time-specific association between PERS and PAEs; such that PERS was more positively associated with PAEs at age 11, than at age 12. Together, our findings highlight age-related changes in PAEs and NAEs, their intercorrelations, and their time-specific associations with impulsivity in 10–13 year old youth.

While some studies propose increasing positive beliefs and diminishing negative beliefs about the effects of alcohol over time (Bekman et al., 2011), others propose a coexistence or even a positive correlation (Grube and Agostinelli, 1999), or negative beliefs stabilizing before decreasing (Scheffels et al., 2023). Our findings partially support both theories indicating that while overall PAEs and NAEs were negatively correlated, their respective trajectories were not anti-correlated. Specifically, PAEs increased gradually through the ages of 11–13, and NAEs only showed an initial increase from the ages of 11–12 and then remained unchanged between 12 and 13 years, emphasizing a pronounced ambivalence regarding AEs, particularly during the 11–13-year age range (Pinquart and Borgolte, 2022). Such complex interplay emphasizes the need to understand developmental trajectories of PAEs and NAEs, and their dynamic relationships. As the ABCD Study continues to collect PAE and NAE data in subsequent years, trajectories of AE development can be further examined during later adolescent years. Moreover, these results provide a rationale for studies such as the recently NIH-funded HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) Study to acquire similar data and provide the opportunity to study time dependent changes in AEs earlier than 9–11 years of age.

Our findings revealed key associations between self-reported impulsive tendencies and AEs. Prior studies exploring this relationship are rooted in the Acquired Preparedness Model (APM), which suggests a relationship between impulsivity, expectancies and drinking behaviors (Corbin et al., 2011). Our findings revealed that alcohol-naïve youth with higher PAEs’ exhibited greater SS and greater PRE. SS has been shown to be associated with stronger PAEs, thus contributing to an increased likelihood for future engagement in risky alcohol use (Scott and Corbin, 2014, Wasserman et al., 2020). Despite the proven relevance and reliability of SS within the UPPS-P Scale, our internal reliability analyses revealed it to have the lowest Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.477). Nonetheless, SS remains a potential risk factor that may contribute to alcohol use behaviors.

In addition, consistent with our findings, PRE has previously been associated with PAEs (Banks and Zapolski, 2017), which in turn has shown to facilitate drinking behaviors (Wadell et al., 2022). PRE within the APM framework is more consistently associated with the onset of drinking behaviors and subsequent use of alcohol, particularly the frequency of drinking in a middle-school cohort (Peterson et al., 2018).

We further observed greater PU was associated with lower NAEs, suggesting youth who respond rashly to their positive emotions may have lower negative beliefs about alcohol. This association may be clinically significant since higher PU has been linked to future alcohol initiation (Settles et al., 2010). Although we did not observe an association between PU and PAEs, such an association has previously been reported in youth transitioning from elementary to middle school. Furthermore, the existence of negative beliefs about alcohol does not always discourage high impulsive youth from drinking (Finn et al., 2005). This may be explained by the development of PAEs and NAEs simultaneously (Scheffels et al., 2023), which we have also observed between ages 11–12, and their intercorrelations at age 11. Though it is not entirely established in the literature, our findings suggest youth with high PU and beliefs that alcohol has fewer negative outcomes, may be at potential risk for engaging in risky drinking. Despite the predominant focus on PAEs in the literature, it is imperative to acknowledge the substantial impact of NAEs on alcohol-related decision-making. This study underscores the significance of NAEs, a factor often overlooked in the literature.

Perhaps one of the most novel findings of the current study is the time-specific change in association between PERS and PAEs. Specifically, the relationship between PERS at baseline was significantly more positive with PAEs at Age 11 than it was with PAEs at Age 12. Existing studies have not yet established a definitive association between PERS and PAEs, and certainly not in a time-specific manner. Therefore, interpretation of these results proves to be challenging. Particularly, in the present study, we did not observe any significant relationship between PERS and the mean PAEs across all ages. As such, the observed change in the strength of the association from Age 11 to Age 12 is indicative of the time of assessments being further apart. Beyond this interpretation, it underscores the need for continued investigation of these time-specific associations. Past studies have linked PERS to the initiation and escalation of alcohol use, raising some possibility that the relationship between PERS and alcohol initiation may be mediated by PAEs, particularly in late childhood and early adolescence. However, continued research within the ABCD cohort is needed to ensure the observed patterns persist over a longer period and as youth initiate alcohol use.

There were no significant associations between behavioral impulsivity and AEs. The lack of association between impulsive choice and AEs may be due to CCT being a single item outcome with unknown psychometrics, potentially affecting its specificity and ability to detect relationships. To address this, future studies can explore the relationship between impulsive choice and AEs using the DDT when more time points are available. Furthermore, while the SST is a widely used measure for response inhibition, earlier studies have indicated that the presence of stop signals leads to anticipated responses, potentially obscuring true impulsive behaviors (Vink et al., 2015, Zandbelt and Vink, 2010). Additionally, the inconsistencies in the stop delays in the ABCD study’s implementation of the SST have shown to lead to incorrect SSRT computation (Bissett et al., 2021). Such concerns potentially undermine SST’s ability to robustly reflect impulsive action. Beyond these technical considerations, behavioral impulsivity may not be adequately captured by one-time SST assessment inside an MRI scanner and can vary in response to environment or biological conditions (Nguyen et al., 2018). Consequently, ecological momentary assessments (McCarthy et al., 2018) with data collected at various time points (e.g., every 30 minutes) may better reflect state impulsivity and allow us to capture associations.

Limitations of the current study include our inability to establish causal relationships as the ABCD study is an observational study. Despite efforts to consider various potentially confounding factors contributing to the development of PAEs and NAEs by controlling for demographic, clinical and environmental factors, there may be unaccounted associations in AE development within the study. Furthermore, another potential limitation is the use of CCT for measuring impulsive choice. While the DDT is more commonly used, it was not available at Age 10, necessitating the use of the CCT, which was limited to a two-level questionnaire. Additionally, validity of the CCT questionnaire could not be assessed. However, (Kohler et al., 2022) demonstrated relative concordance between CCT at Age 10 and DDT at Age 11, indicating the cash choice measure tracks impulsive choice effectively. Lastly, the current study examines the development of PAEs and NAEs within a limited timeframe (11 – 13 years old). However, ABCD study will provide subsequent data releases with additional time points, allowing for the exploration of more extended trajectories and time-dependent relationships of PAEs and NAEs. Tracking participants throughout adolescence provides an opportunity to explore alcohol use onset, behavioral manifestations of alcohol use, and subsequent problematic drinking behaviors. Using ABCD's longitudinal nature, future studies can explore relationships in both alcohol-naïve and exposed youth, highlighting antecedent risk factors' impact on underage drinking.

6. Conclusions

In summary, our study provided novel insights into the trajectory of potential risks for alcohol use initiation in youth by exploring the dynamic nature of AEs and their associated risk factors through the integration of self-report and behavioral impulsivity measures. Overall, we aimed to provide valuable insights into relationships between impulsivity and the development of AEs. Our findings highlighted PAEs and NAEs changed dynamically over time, necessitating separate exploration as distinct entities, each potentially associated with unique risks for future alcohol consumption. Examining this relationship in an alcohol naïve cohort provides a unique opportunity to better understand the interplay between innate tendencies and social influences in shaping alcohol use onset. By understanding these relationships, alcohol use and misuse intervention and prevention programs may effectively equip youth with the knowledge and tools to navigate stimulating environments outside of the home and make informed decisions regarding alcohol use.