Abstract

Background: A mounting body of evidence suggests that polysubstance use (PSU) is common among people who use opioids (PWUO). Measuring PSU, however, is statistically and methodologically challenging. Person-centered analytical approaches (e.g., latent class analysis) provide a holistic understanding of individuals' substance use patterns and help understand PSU heterogeneities among PWUO and their specific needs in an inductive manner. We reviewed person-centered studies that characterized latent patterns of PSU among PWUO.

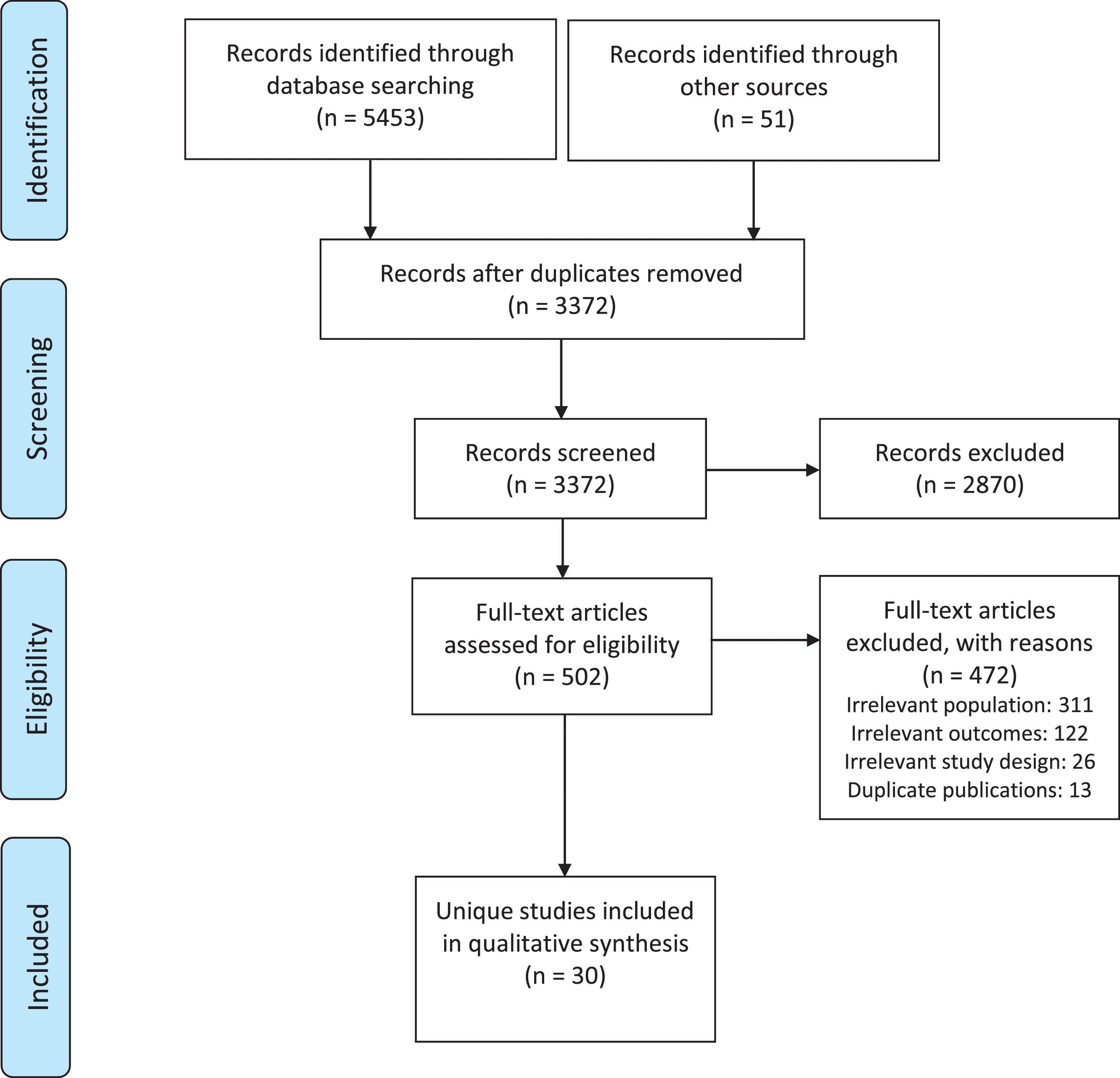

Methods: We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from inception, through to June 15, 2020, for empirical peer-reviewed studies or gray literature that reported on latent classes of PSU among PWUO. Two independent reviewers completed the title, abstract, full-text screening, and data extraction. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, and quality of reporting was evaluated using the Guidelines for Reporting on Latent Trajectory Studies checklist. Studies' findings were summarized and presented in a narrative fashion.

Results: Out of the 3372 initial unique studies identified, 30 were included. PSU operationalization varied substantially among the studies. We identified five distinct PSU latent classes frequently observed across the studies: Infrequent/low PSU, PSU primarily involving heroin use, PSU primarily involving heroin and stimulant use, PSU primarily involving stimulant use, and frequent PSU. Belonging to higher frequency or severity PSU classes were associated with frequent injection drug use, sharing needles and paraphernalia, high-risk sexual behaviours, as well as experiences of adversities, such as homelessness, incarceration, and poor mental health.

Conclusion: PSU patterns vary significantly across different subgroups of PWUO. The substantial heterogeneities among PWUO need to be acknowledged in substance use clinical practices and policy developments. Findings call for comprehensive interventions that recognize these within-group diversities and address the varying needs of PWUO.

Introduction

There is little consensus when it comes to defining polysubstance use (PSU); it is often used as a broad term to describe the use of ≥2 different substances or classes of substances either simultaneously or separately over a defined period (Connor, Gullo, White, & Kelly, 2014; Tomczyk, Isensee, & Hanewinkel, 2016). A growing body of international evidence suggests that PSU is particularly frequent among people who use opioids (PWUO) (Chen et al., 2019; Harrell, Mancha, Petras, Trenz, & Latimer, 2012; Hassan & Le Foll, 2019; Yang et al., 2018). Moreover, drug overdose deaths often involve several drugs in addition to opioids (Crummy, O'Neal, Baskin, & Ferguson, 2020). For example, in the Canadian province of British Columbia, the most detected drugs in illicit drug toxicity deaths during the past four years were fentanyl (83%), cocaine (50%), amphetamines (34%), and heroin (15%) (BC Coroners Service, 2020). Similar patterns are observed in the United States, where National Vital Statistics System reported cocaine overdose deaths involving any opioids increased from 29% to 63% between 2000 and 2015 (McCall Jones, Baldwin, & Compton, 2017).

Measuring PSU is statistically and methodologically challenging. Most studies have assessed PSU using contingency tables of several single drugs, leading to small cell sizes or highly skewed distributions and, therefore, limited or biased analyses or interpretations (Afshar et al., 2019; Connor et al., 2014; Crummy et al., 2020; Liu & Vivolo-Kantor, 2020; Liu, Williamson, Setlow, Cottler, & Knackstedt, 2018). Despite inconsistencies over what constitutes PSU, studies have consistently associated PSU with an increased risk of numerous poor health outcomes (Carter et al., 2013; Connor et al., 2013; Hedden et al., 2010; Quek et al., 2013; Timko, Han, Woodhead, Shelley, & Cucciare, 2018; Trenz et al., 2013).

Considering the importance of characterizing the distribution and correlates of PSU for overdose prevention programs and harm reduction interventions, methodological developments have been undertaken to help better identify and uncover subpopulations with distinct PSU patterns through person-centered methods (Lanza & Cooper, 2016; Lanza & Rhoades, 2013; Lanza, Collins, Lemmon, & Schafer, 2007; Tomczyk et al., 2016). In contrast with variable-centered approaches that focus on the relationship between individual variables and assume homogeneity among the population of interest with regards to how predictors impact the outcome of interest, person-centered approaches (e.g., latent class analysis [LCA], latent transition analysis [LTA], latent profile analysis [LPA], latent growth mixture model [LGMM]) assume heterogeneity among the population of interest with regards to how outcomes of interest are influenced by predictors. Indeed, these methods examine the data using an inductive lens, analyze participants’ response patterns to certain individual indicator variables that measure specific substance use practices, and reveal unobserved typologies or classes of PSU via statistically transparent and reproducible methods (Lanza & Cooper, 2016; Lanza & Rhoades, 2013).

Given the wide range of substances available and the challenges in measuring PSU in a clinically meaningful manner, it is unclear what types of PSU patterns are prevalent among PWUO. This systematic review aims to classify, characterize, and summarize the latent patterns of PSU among PWUO. Identifying latent PSU classes and associated determinants among PWUO helps facilitate and inform the implementation of evidence-based interventions and preventative measures aimed at addressing the ongoing overdose epidemic.

Methods

Databases and search strategy

Following the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines (McGowan et al., 2016) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009), we searched for empirical peer-reviewed studies or gray literature on latent classes of PSU among PWUO from inception, through to June 15, 2020 (See Table S1 for PRISMA checklist). The search concepts, databases searched, and information about the review’s protocol registration are presented in Table 1, and a sample search strategy is available in Table S2.

Table 1. An overview of the search strategy.

Search Concepts

Note: Search terms were combined using appropriate Boolean operators, and included keywords and subject heading terms relevant to three main concepts. Studies were limited to humans and no language restriction was applied. | Polysubstance use (e.g., polydrug use OR polysubstance use OR concurrent drug use OR multiple drug use) AND opioid use (e.g., opioid dependence OR heroin OR fentanyl OR morphine OR methadone OR oxycodone OR opioid agonist therapy) AND latent class approaches (e.g., latent class analysis [LCA] OR latent transition analysis [LTA] OR latent profile analysis [LPA]). |

Databases

Note: Search terms were tailored to fit each database requirements. | MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (first 300 records) were systematically searched. We also hand searched bibliographies of relevant published works and previous reviews, and relevant recent conference proceedings (i.e., Harm Reduction International Conference, American Psychiatric Association), and gray literature databases and dissertations. |

Protocol Registration | Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/6vjdf/ ). |

Inclusion criteria

Empirical studies of any design (i.e., observational, experimental, cross-sectional, and cohort) were considered for inclusion if they identified latent classes of substance use among PWUO. Opioid use was assessed based on the following criteria: i) participants had regular opioid use; ii) were clinically assessed as having opioid use disorder (OUD) based on The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] or other validated tools (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); or iii) participants were receiving treatment for OUD. Studies with mixed populations of PWUO and people with other substance use disorders were considered if they provided separate analyses for participants with PWUO or if more than 50% of the participants were PWUO. Studies were included if they had reported categorical or continuous measures of substance use during any time interval (e.g., last year, last six months, last month, current). Studies were only included if they reported latent classes of substance use through various latent class analytical approaches (e.g., LCA, LTA, LPA, LGMM). Eligible studies had to report details about latent classes identified and variables used as outcome indicators (i.e., individual indicators that contributed to identifying latent classes). Studies were excluded if they used latent class analyses for variables other than substance use characteristics (e.g., HIV or overdose risk).

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (MK and AP) completed the title and abstract screening. Studies that met our inclusion criteria or were unclear were retained for full-text screening, which was done by two independent reviewers (MK and AP). Disagreements over the inclusion of studies were resolved through discussion throughout the screening process. Duplicate studies were identified and excluded.

Data extraction and analysis

We developed a data extraction sheet and pilot-tested it by two independent authors (MK and AP). Two reviewers (MK and AP) completed data extraction independently, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data were extracted on study characteristics, participant characteristics, and outcome characteristics. Given the considerable conceptual heterogeneity of covariates (e.g., inclusion of a range of sociodemographic or behavioural variables in the multivariable analyses) and outcomes included in the analyses across the studies (e.g., PSU operationalization using different self-reported or clinical measures as well as the inclusion of various outcome indicators in the latent analyses), no meta-analysis was conducted, and study findings were summarized and presented in a narrative fashion. Primary latent classes and sub-classes of PSU were identified and presented.

Quality assessment

We used a modified version of Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (Wells et al., 2000) to assess the risk of bias in the included studies independently. The tool uses several components to evaluate selection bias, comparability, and outcome assessment. Given the review’s focus on latent analyses, we also used a modified version of the Guidelines for Reporting on Latent Trajectory Studies (GRoLTS) checklist (Van De Schoot, Sijbrandij, Winter, Depaoli, & Vermunt, 2017) to assess the specific methodological quality of the included studies. The modified GRoLTS checklist (Petersen, Qualter, & Humphrey, 2019) contains 15 yes/no items. Using this checklist is important in critical appraisal of LCA, LPA, or LTA studies and ensuring transparency and interpretability of their results.

Results

Out of the 3372 initial unique records identified, 30 met our inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of the study screening process.

Study settings and participants

An overview of the included studies is presented in Table 2. Although all studies included a sub-population of PWUO, their definition of opioid use varied greatly and included a range of criteria across the studies (e.g., receiving opioid agonist therapy [OAT] medication, self-reported recent use of illicit and/or non-prescribed opioids, meeting DSM criteria for OUD). Moreover, the inclusion criteria of the individual studies varied considerably and included a wide range of participants, such as people admitted to emergency departments, people receiving OAT, people involved with the justice system, people accessing harm reduction services, social-economically disadvantaged people who inject drugs (PWID), and other PWUO recruited through various large-scale surveys.

Overall, three studies were longitudinal, and 27 were cross-sectional. The mean/median age of the participants was between 30 and 45 years old in most studies. One study had recruited younger people with a mean age of 21, and one included primarily 50+ year-old participants. Two studies did not report any information on the sex or gender of the participants, and none reported sex- or gender-stratified analyses for latent classes. The sex ratio for the studies ranged from 43.7% males to 85.8% males. Only 16 studies reported ethnicity ratios among their participants. The participants in most studies were White, but race/ethnicity ratios significantly varied from 6% White to 93.2% White. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 16), three in Australia, three in Mexico, two in England, two in Canada, and one in Russia and Estonia, Puerto Rico, Norway, and China, each. Two studies in Mexico were on the same population but were both included given their different methodology (i.e., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) and dissimilar nature of classes identified.

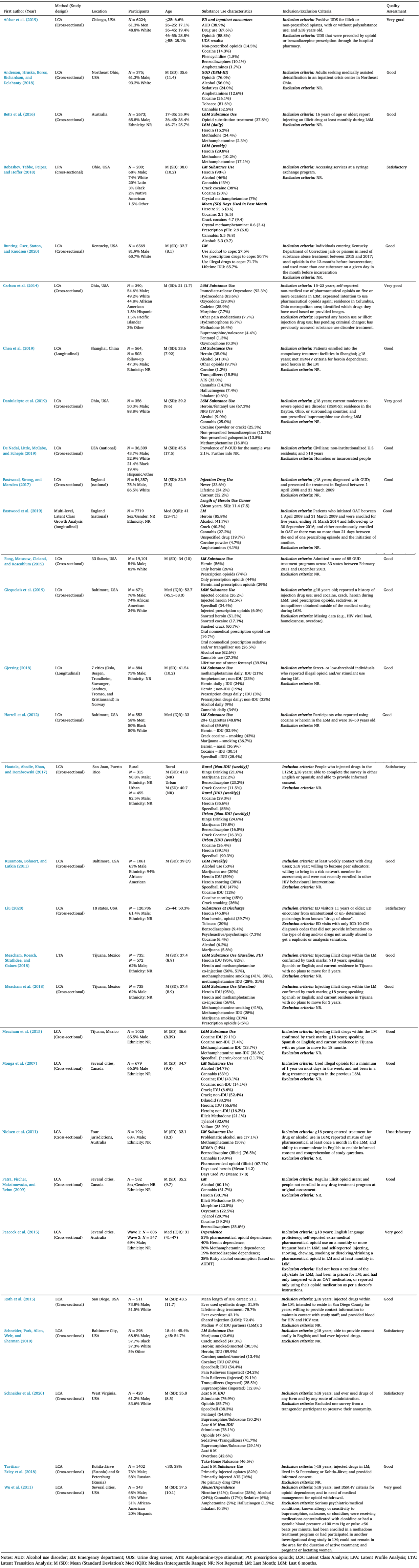

Table 2. Overview of included studies in the systematic review of latent polysubstance use among people with opioid use disorder.

PSU operationalization

PSU operationalization varied substantially among the studies and was measured based on a wide range of metrics across the studies: clinical diagnosis of dependence or substance use disorder using a standard tool (e.g., DSM-III, DSM-IV, DSM-5, Addiction Severity Index) in five, lifetime use in one, last six-month use in nine studies, last-month use in ten studies, combined lifetime and last month in one study, combined last-year and weekly in one study, combined last six months and daily/weekly in two studies, and upon discharge from a treatment facility in two studies. Moreover, six studies used an indicator of simultaneous use in their analysis. Two studies that conducted an LPA, also included the mean number of days used in the past month and one did not report a timeline for substance use practices among their participants. Most studies measured substance use via self-reports.

The outcome indicators used in each study are presented in Table 3. Half (n = 15) of the studies limited their outcome indicators to binary variables. Most studies included various outcome indicators of heroin, amphetamines, cocaine, and crack. In addition, a measure of cannabis use was included as an indicator in 17 studies. Moreover, a measure of alcohol use was included as an outcome indicator in 15 studies; only four included validated measures of alcohol use, and the rest mainly included subjective alcohol use measures in the last month or last six months. A measure of illicit prescription opioids (POs) use (e.g., OxyContin, fentanyl) or non-opioid prescription medication use (e.g., benzodiazepines) were also included as outcome indicators of PSU in 12 and 17 studies, respectively.

While most studies only included substance use outcome indicators, a handful of studies include other indicators: four included socio-demographic factors, such as age, sex, and race, four included mental health-related conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), different forms of phobia, and anxiety, one included hospital utilization, and one included physical health, housing status, and lifetime number of overdoses. Moreover, 15 studies included several indicators of a single type of substance (i.e., frequency of use, length of substance use career) in their latent analysis, and 15 studies included an indicator for the route of substance administration (i.e. injection drug use [IDU] vs. non-injection drug use [non-IDU]) in their assessment of classes of substance use patterns. Lastly, two studies focused on specific brands, such as OxyContin and Tylenol, and only two studies included a measure of fentanyl use as a unique indicator in their LCA.

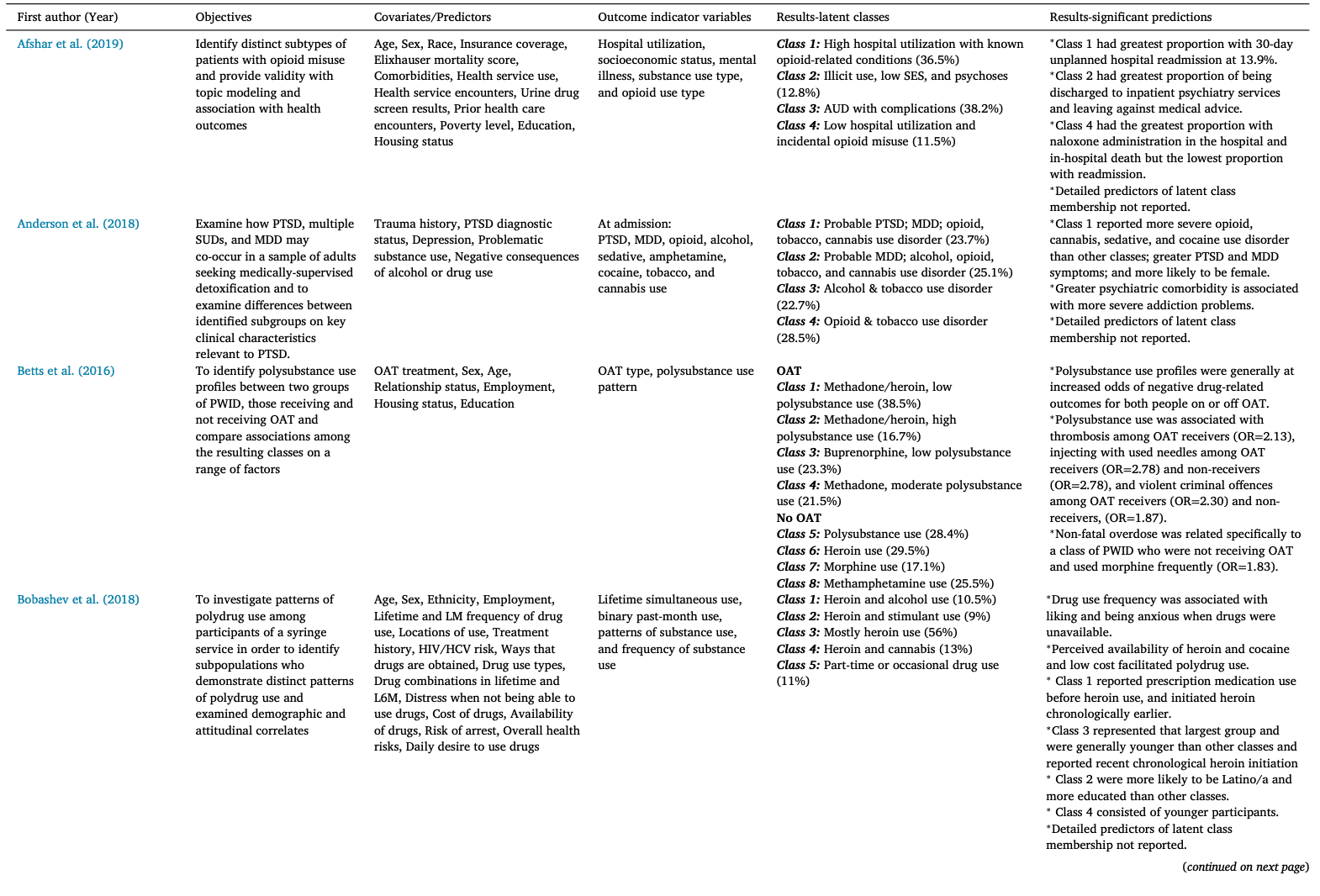

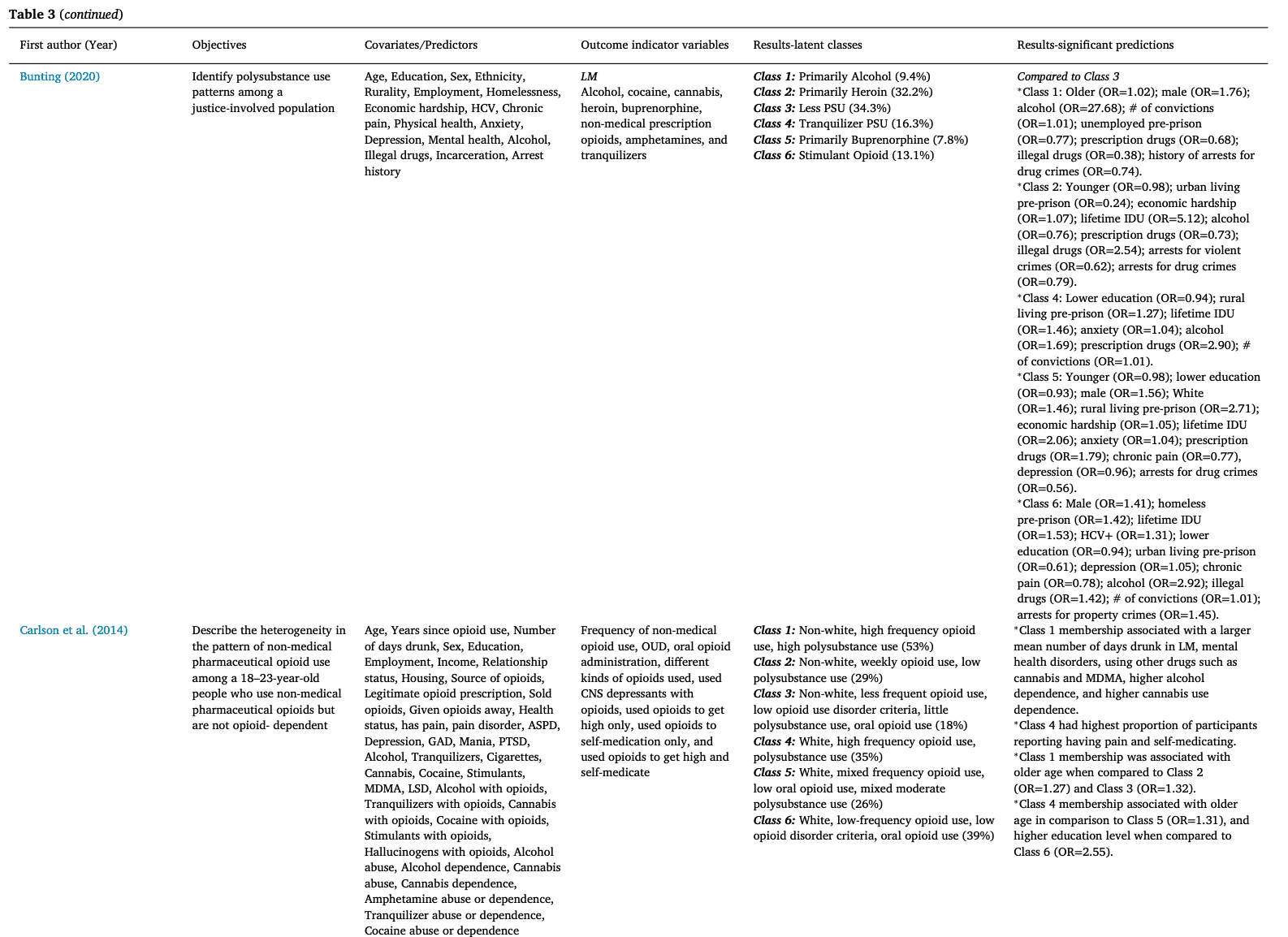

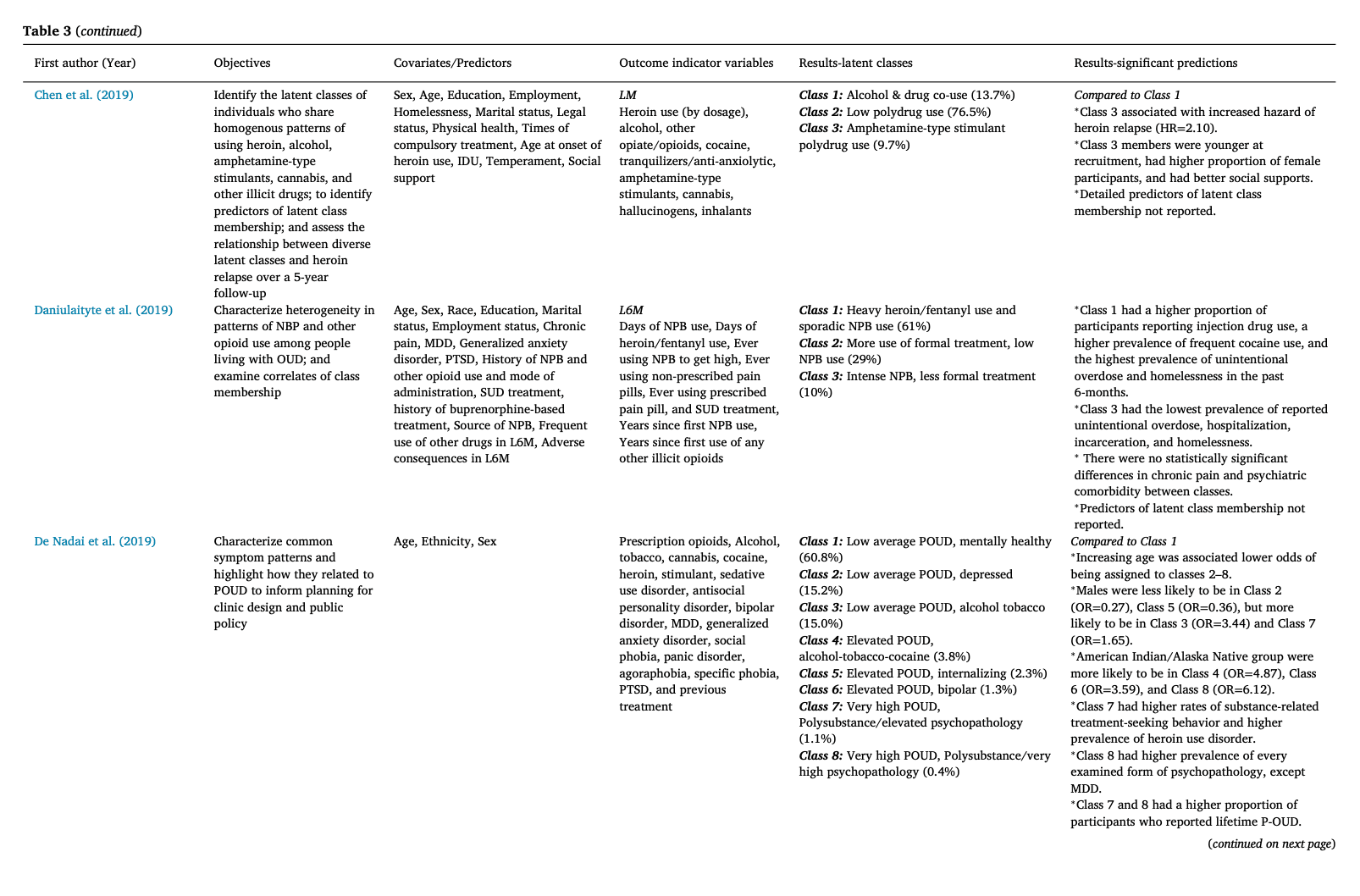

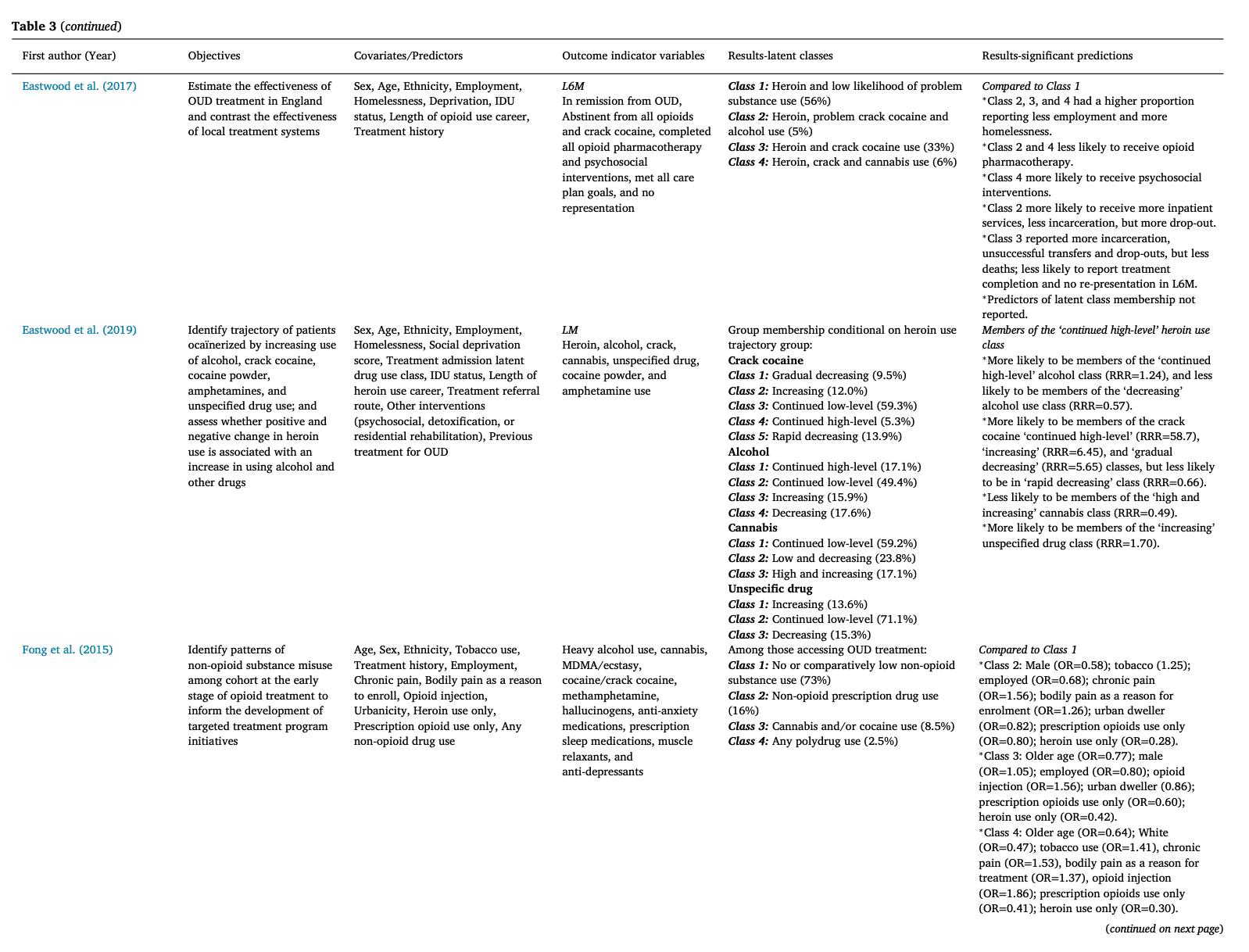

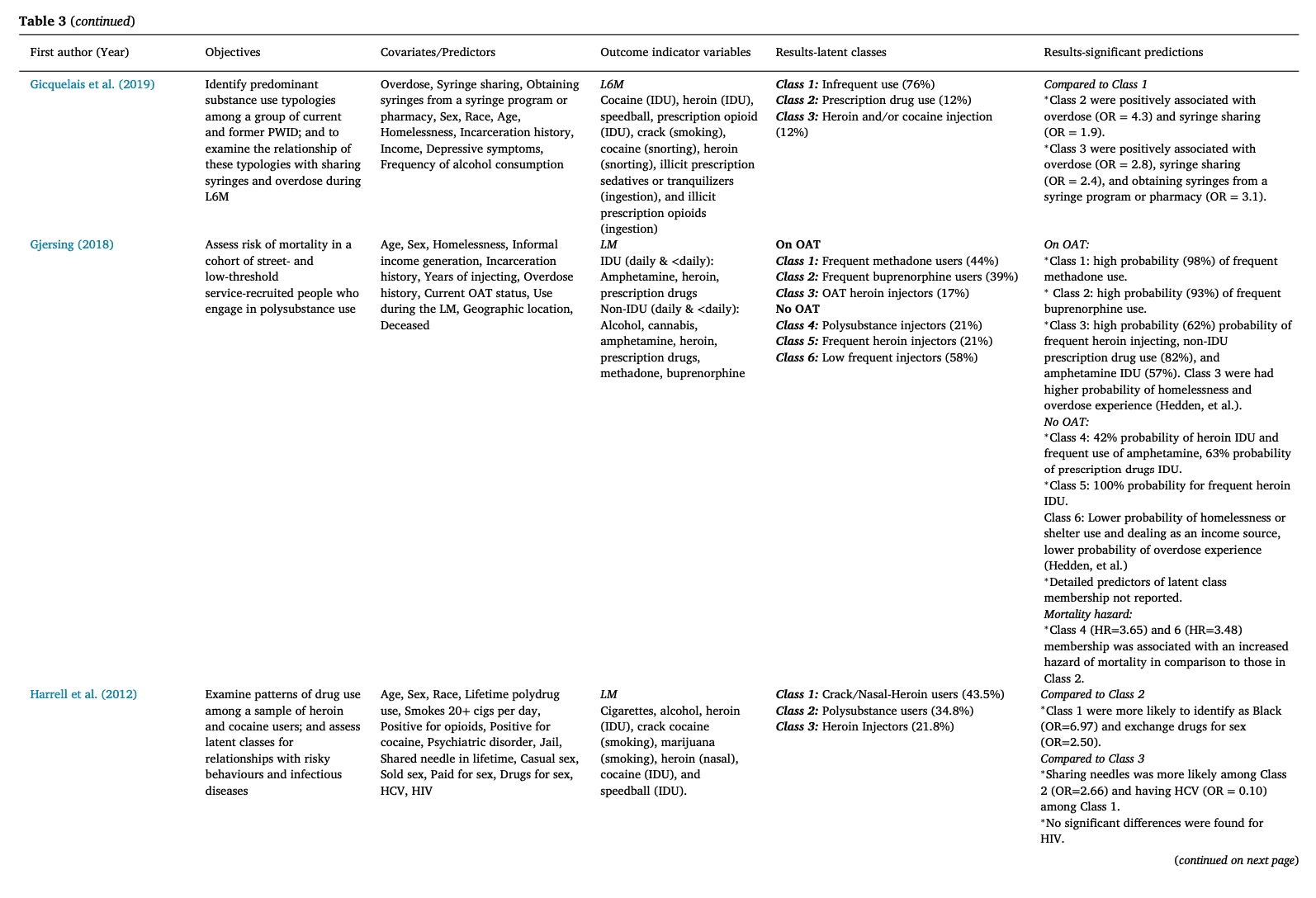

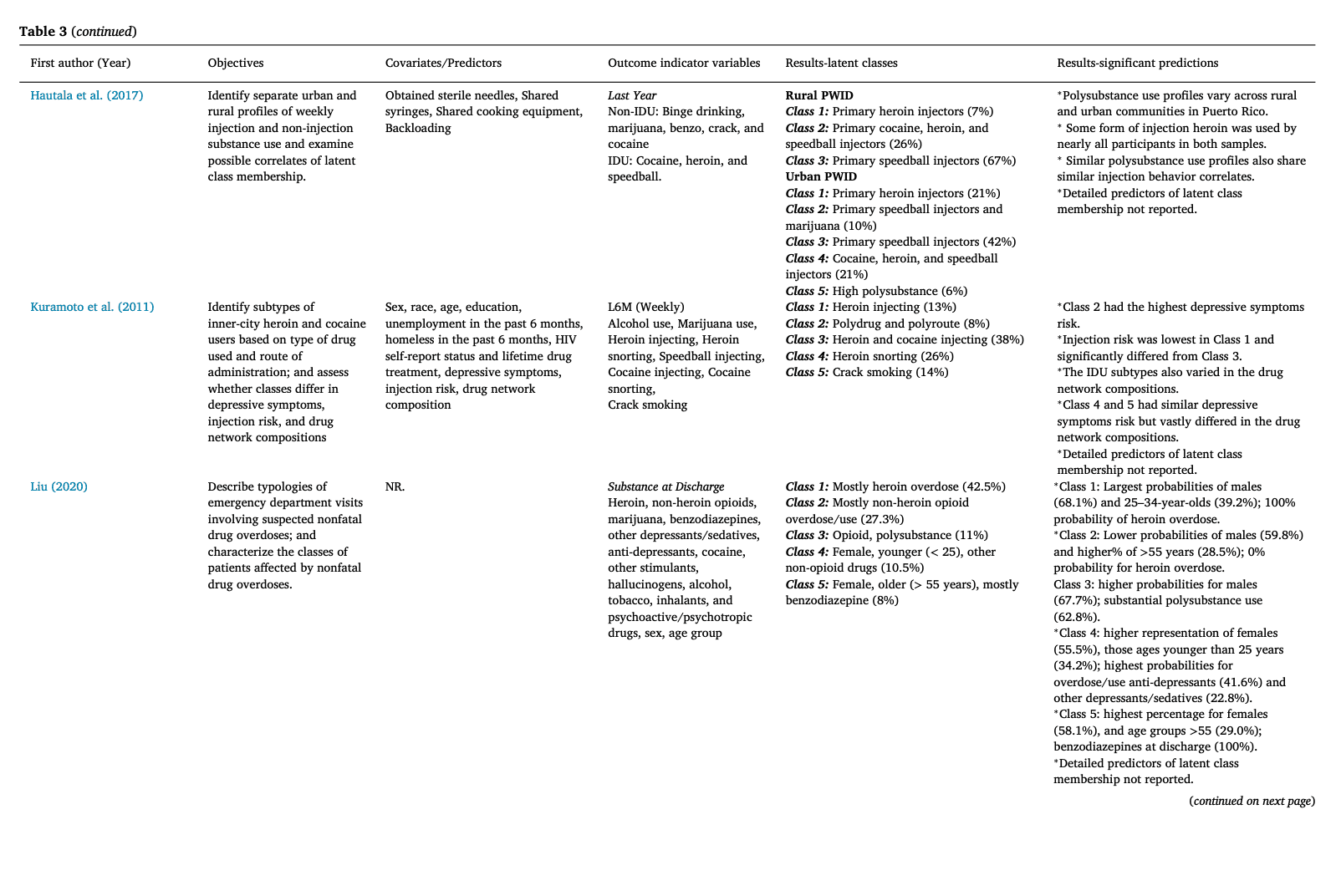

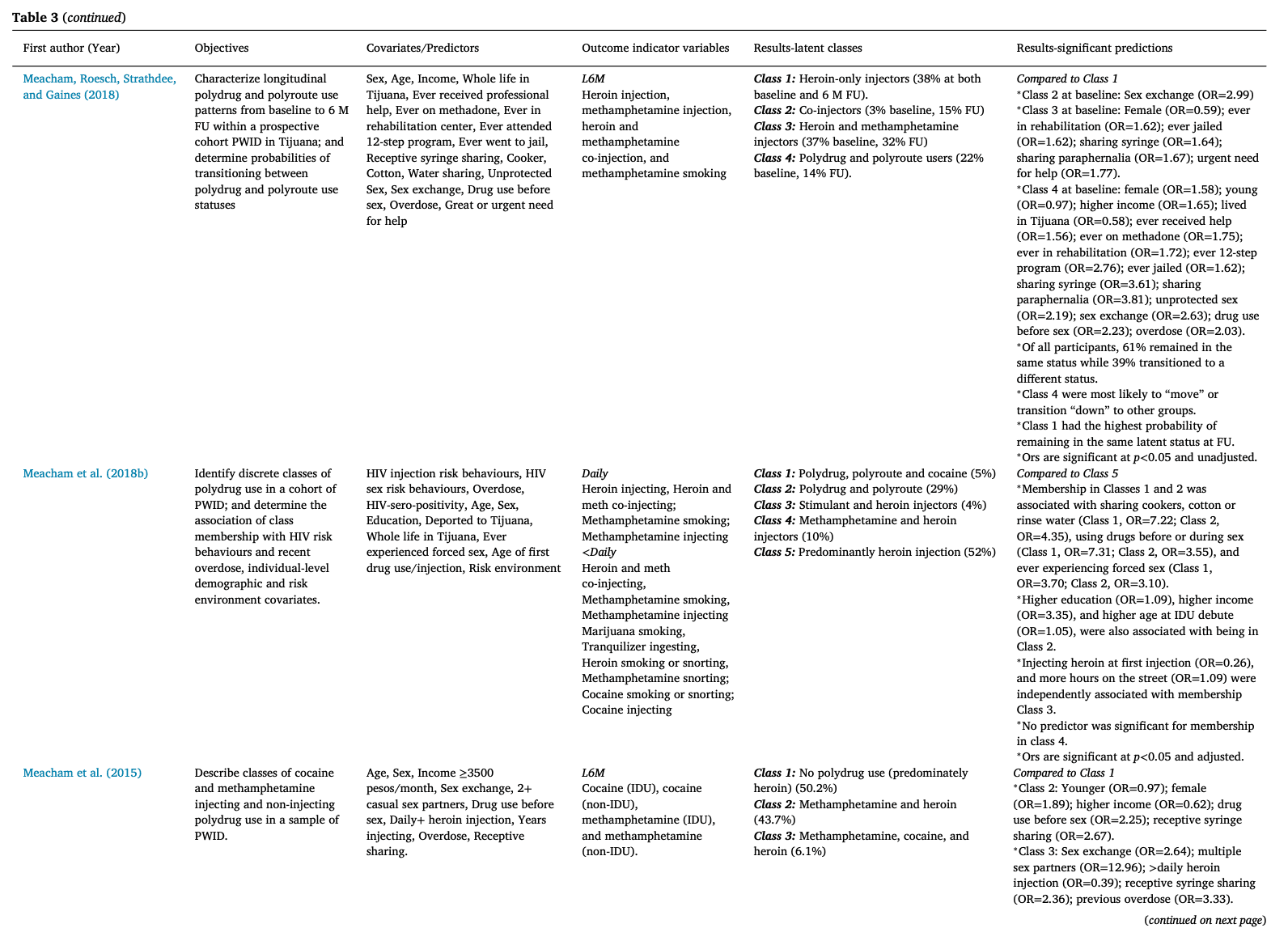

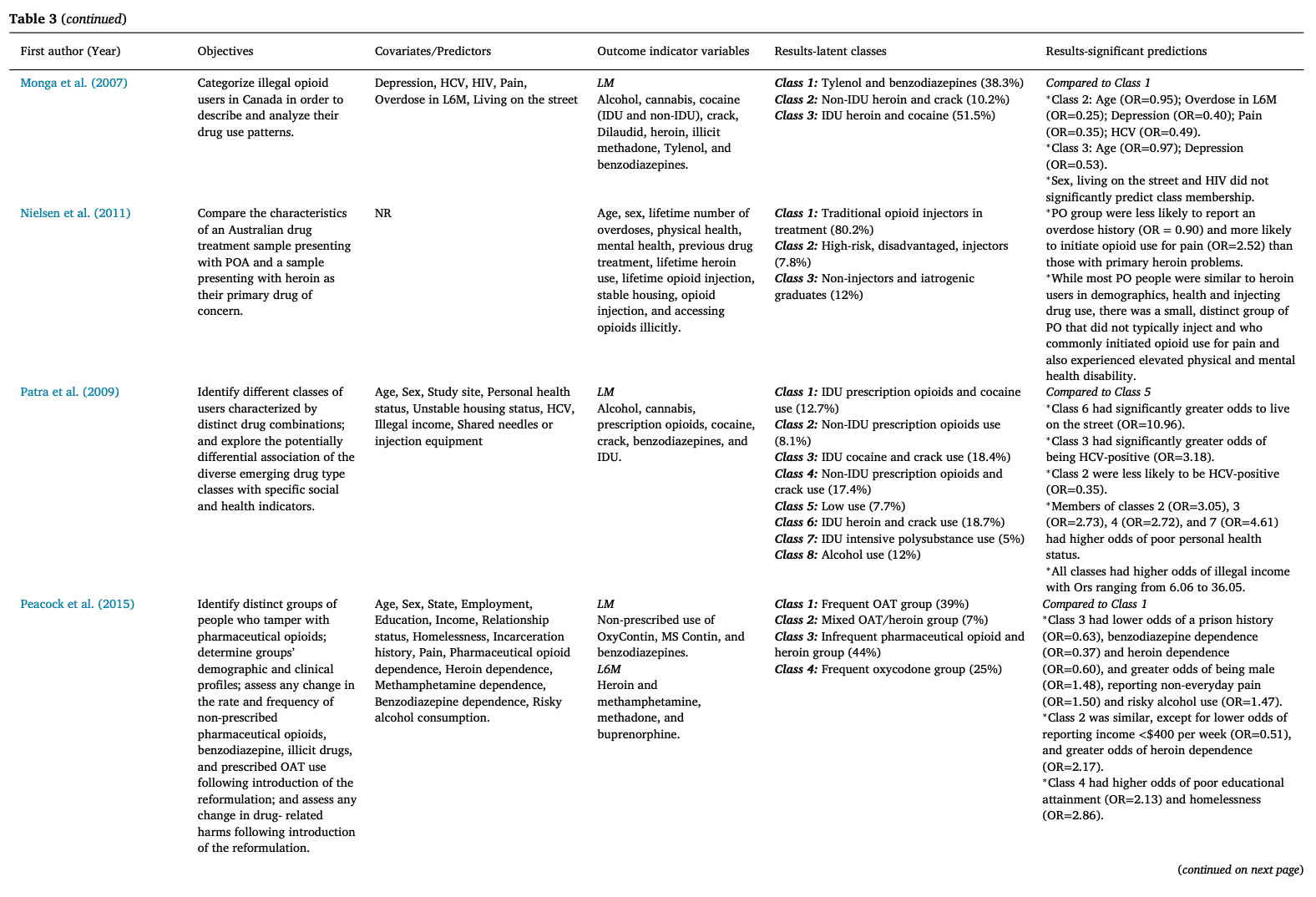

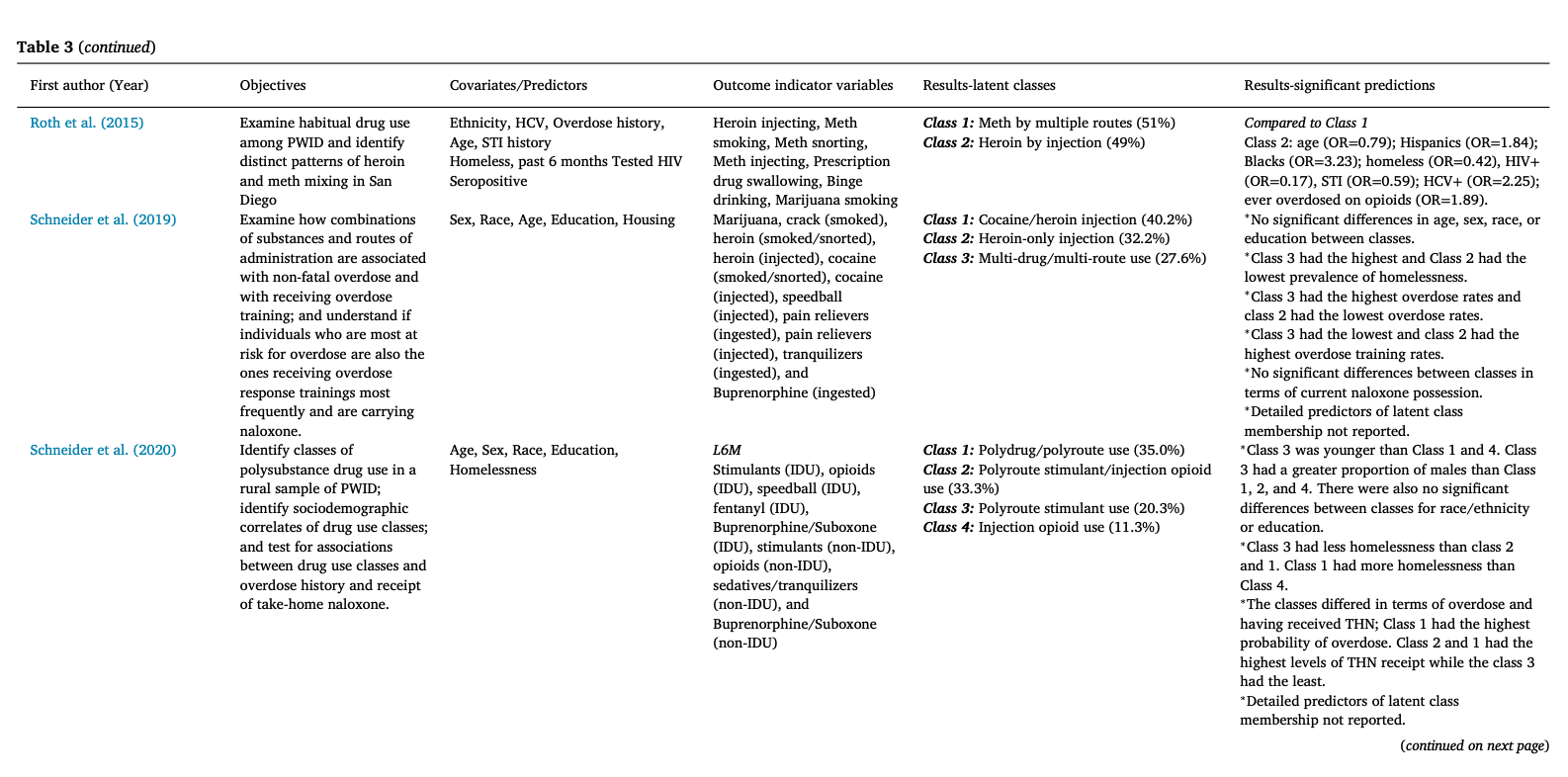

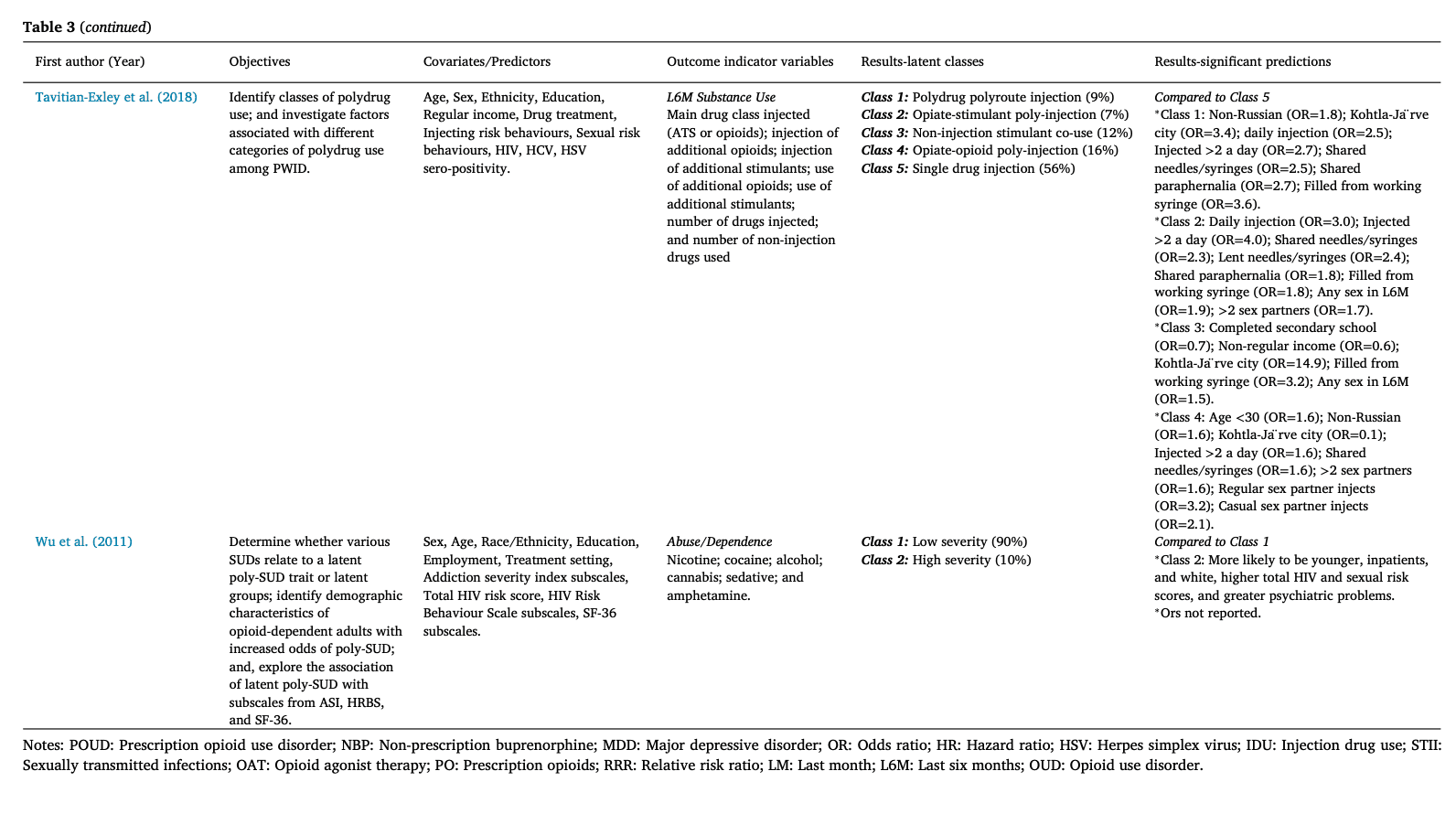

Table 3. Summary of findings of the studies included in the review of latent polysubstance use among people with opioid use disorder.

Latent classes of PSU

The latent classes identified in each study are presented in Table 3. The median number of classes was four, ranging from two to 15 classes. In detail, two studies identified two classes, eight studies identified three classes, seven studies identified four classes, five studies identified five classes, three studies identified six classes, four studies identified seven or eight classes, and one study reported 15 classes. The study with 15 classes reported heroin use conditional on membership in various trajectories of other substance types (Eastwood, Strang, & Marsden, 2019). Only four studies grouped their analyses by another unique characteristic of the participants: being on OAT, urbanicity, and race. Although the classes identified across the studies varied considerably, the following latent classes, presented in Table 4, were found in most studies: Infrequent/low PSU; PSU primarily involving heroin use; PSU primarily involving heroin and stimulant use; PSU primarily involving stimulant use; and Frequent PSU.

While most identified classes fit into the overarching latent classes presented above, some were difficult to fit into a particular group due to variations in measurements and indicators used to build classes. For example, including socio-demographic variables and mental health-related conditions as outcome indicators, was reflected in the final class solutions identified in four and three studies, respectively. Moreover, Afshar et al. (2019) identified classes reflecting the intensity of hospital utilization. Furthermore, eight studies labeled at least one class to indicate a considerable level of alcohol use and five labeled at least one class to indicate a considerable level of cannabis use. In addition, 11 studies labeled at least one class that indicated a considerable level of POs or non-opioid prescription medications. Two studies also identified at least one class suggesting significant tobacco use among their participants and six studies identified at least one class that indicated considerable use of prescribed or non-prescribed OAT medications.

Table 4. Latent polysubstance use classes among people who use opioids across the studies included in the review.

Polysubstance use classes | Characteristics of latent classes and sub-classes |

Infrequent/low polysubstance use | This class was identified in 16 studies and was characterized by low indicator probabilities for polysubstance use. Primary sub-classes included people with low use of POs or non-POs and those with no or infrequent substance use, and proportions reported for this class across the studies ranged from 7.7% to 90.0% (Median: 34.3%). |

PSU primarily involving heroin use | This class was identified in 22 studies and was characterized by polysubstance use with injection or non-injection use of heroin as a primary substance of choice. Primary sub-classes included people who primarily used heroin and opioid agonist therapy medications, heroin and alcohol use, or heroin and POs, and proportions reported for this class across the studies ranged from 7.0% to 80.2% (Median: 32.2%). |

PSU primarily involving heroin and stimulant use | This class was identified in 15 studies and was characterized by polysubstance use with injection or non-injection use of heroin and stimulants as substances of choice, either concurrently or separately over a defined period of time. Primary sub-classes included people who primarily used heroin and cocaine (speedball or co-use separately), heroin and crack, or heroin and methamphetamine (goofball or co-use separately), and proportions reported for this class across the studies ranged from 6.1% to 67.0% (Median: 26.0%). |

PSU primarily involving stimulant use | This class was identified in 13 studies and was characterized by polysubstance use with injection or non-injection use of stimulants as substance of choice. Primary sub-classes included people who primarily use amphetamine-type substances, or crack and cocaine, and proportions reported for this class across the studies ranged from 8.5% to 67.0% (Median: 20.3%). |

Frequent polysubstance use | This class was identified in nearly all included studies and was characterized by persistent polysubstance use with high-frequency injection or non-injection use of multiple drugs simultaneously or separately over a specified period of time. Primary sub-classes included people with polysubstance use of different substances via various routes of administration, polysubstance use including alcohol, or polysubstance use including prescription drugs, and proportions reported for this class across the studies ranged from 1.5% to 53.0% (Median: 20.3%). |

Note: The identified latent polysubstance use classes and sub-classes are among people who use opioids (PWUO). PWUO was defined as those who were using opioids on a regular basis, were assessed to have opioid use disorder, or were receiving treatment for opioid use disorder.

Predictors of latent class membership

Comparisons about latent class memberships need to be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of PSU operationalization across different studies. Of the 30 included studies, 18 reported detailed effect size measures for predictors of latent class membership. Most studies compared their PSU class with lower frequency classes, the details of which are presented in Table 3.

Sociodemographic predictors

Most studies compared the classes based on their sociodemographic characteristics; however, most examined comparisons based on age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity. The findings of the studies regarding the association of age and substance use class membership were relatively consistent and increasing age was often associated with belonging to higher frequency or severity classes; however, a subset of studies reported no significant association between class membership and age.

Among 28 studies that reported on participants’ sex, no study reported any details about participants’ gender, and some confused sex with gender. Overall, the association of sex and latent classes of PSU were inconsistent. For example, compared to males, females were more likely to belong to adverse mental health, opioid, tobacco, cannabis use disorder classes, amphetamine-type stimulant polydrug use class, low-frequency POs use and depressed class, non-opioid prescription drug use class, non-opioids and benzodiazepine classes, polydrug and polyroute users class, and methamphetamine and heroin class. Conversely, compared to females, males were more likely to belong to the following classes: primarily alcohol, buprenorphine, and benzodiazepine use, very high-frequency POs, polysubstance, and elevated psychopathology, cannabis and/or cocaine use, PSU and heroin overdose, heroin and methamphetamine injectors, infrequent POs and heroin, and polyroute stimulant use. Several studies reported no significant association between class membership and sex.

Among 16 studies that reported on the race/ethnicity of the participants, 11 reported detailed associations between this variable and class memberships. Overall, the findings regarding the association of race/ethnicity and PSU classes were inconsistent and studies had used various racial/ethnic classifications in their assessments. For example, compared to non-Whites, White people were more likely to belong to buprenorphine use class, less likely to belong to polydrug use class, and more likely to be classified as high severity users. Conversely, compared to White people, Hispanic and Black people were more likely to belong to heroin IDU class, Black people were more likely to be classified as crack/nasal heroin users, and American Indigenous people were more likely to belong to elevated POs, alcohol-tobacco-cocaine, bipolar, and polysubstance/very high psychopathology classes. Some studies reported no significant association between class membership and race/ethnicity.

PSU characteristics among people receiving OAT

A measure of prescribed OAT medications (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) was included in four studies, two of which presented stratified analyses based on receipt of OAT. Betts et al., stratified PSU patterns among PWID based on OAT status and reported that among those on OAT, the classes identified reflected co-use of multiple drugs in addition to OAT medication. However, the probability of intensive PSU was higher among those who were not receiving OAT. Gjersing et al., also stratified their analysis based on OAT status and reported those on OAT to be less likely to practice PSU. Moreover, those engaging in PSU among non-OAT receiving PWID were at an increased risk of premature mortality. Daniulaityte et al., characterized the heterogeneous patterns of prescribed and non-prescribed buprenorphine among people with OUD and showed that those receiving formal addiction treatment to be less likely to report intensive non-prescribed buprenorphine. Notably, they highlighted that non-prescribed buprenorphine use among the participants was primarily driven by self-treatment practices to deal with withdrawal symptoms and much less for euphoric purposes. Lastly, Peacock et al., showed that among those with frequent prescribed OAT use, other illicit drugs and non-prescribed opioids were used less and infrequently compared to those not receiving prescribed OAT.

Outcomes associated with latent class membership

Among studies that reported outcomes associated with latent class membership, in comparison with lower frequency groups, belonging to higher frequency or intensity PSU classes were associated with increased odds of various behaviours, such as use of psychiatric services, mental health comorbidities, poor drug-related outcomes, frequent IDU, receptive needle and paraphernalia sharing, thrombosis, engaging in violent behaviours, non-fatal overdose, high-risk sexual behaviours, sexualized substance use, as well as experiences of adversities, such as homelessness, incarceration, unemployment, chronic pain, and HCV sero-positivity. Mortality risk was only assessed in one cohort study of street- and low-threshold service-recruited people who engaged in PSU practices in Norway, where membership in the polysubstance injectors and low-frequency injector classes not receiving OAT, was associated with an increased hazard of mortality in comparison to frequent buprenorphine users (Gjersing & Bretteville-Jensen, 2018).

Quality of the evidence

As presented in Table S3, most studies were of satisfactory quality in terms of risk of bias as evaluated by a modified version of Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. While most studies had a sufficient sample size required for LCA (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018), had comparable participants, and were statistically sound, most suffered from measurement biases in their outcome and exposure ascertainment. The quality of LCA studies, which was assessed by a modified GRoLTS checklist, are presented in Table S4 and identified several limitations across the included studies.

Discussion

We systematically reviewed 30 studies that applied a latent analytical approach to identifying PSU patterns among PWUO and identified five distinct PSU patterns: Infrequent/low PSU in 16 studies, PSU primarily involving heroin use in 22 studies, PSU primarily involving heroin and stimulant use in 15 studies, PSU primarily involving stimulant use in 13 studies, and frequent PSU in almost all included studies. Membership in higher frequency or intensity PSU classes was associated with several individual- and structural-level adverse mental and physical health outcomes.

Our findings of PSU patterns among PWUO are relatively comparable but not compatible with a previous review of PSU patterns in the general population, which classified PSU into clusters, including no or limited use (alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis), moderate use (“limited range” and amphetamines), and extended use (“moderate range”, illicit prescription medications, and other illicit substances) (Connor et al., 2014). Our findings also diverge from several previous reviews on PSU clusters/classes among adolescents, which mainly identified different subgroups of adolescents using varying frequencies and amounts of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis (Halladay et al., 2020; Tomczyk et al., 2016). These differences could be attributed to the dissimilar approaches in PSU measurement as well as distinctive behavioural characteristics and substance use patterns of PWUO in comparison with people in the general population or adolescents who may be primarily experimenting with PSU. Future research could benefit from improving the instrumentation of and screening for PSU in clinical settings. Developing pilot-tested and standardized screening tools for PSU that can measure different patterns of PSU, routes of administration (e.g., injection, non-injection), reasons for practicing PSU (e.g., recreational, withdrawal management), and recent experiences (e.g., last week, current) can be beneficial to addiction research and clinical practice. Such screening tools could help increase the understanding of PSU, aid in better identification of people engaged in higher-risk practices, help define meaningful treatment-related outcomes (i.e., client-centered non-abstinence focused), and tailor care and treatment plans accordingly.

Although our results suggested certain distinct classes of PSU among PWUO, PSU seems to be often the norm rather an occasional practice or an exception among a minority group of PWUO. Indeed, our findings are in line with a growing body of evidence that suggests concurrent and/or sequential use of multiple substances, including but not limited to stimulants, opioid/non-opioid prescription medications, and alcohol, is a common practice among PWUO (Cicero, Ellis, & Kasper, 2020; Crummy et al., 2020; Jones, Mogali, & Comer, 2012; Witkiewitz & Vowles, 2018). This established body of evidence points to a range of recreational or therapeutic reasons for PSU among PWUO. First, combining substances that have dissimilar impacts on CNS (e.g., opioids and benzodiazepines or stimulants and opioids, such as goofballs and speedballs) could magnify their euphoric effects (Crummy et al., 2020; Darke, Duflou, Torok, & Prolov, 2013; Jones et al., 2012; Timko et al., 2018; Wang, Chen, Chen, Chou, & Chou, 2014; Witkiewitz & Vowles, 2018). Second, stimulants may be used concurrently or consecutively with heroin to reduce the undesirable experiences of opioid cravings or withdrawal (Harris et al., 2013), or balance out the effects of the heroin high (Al-Tayyib, Koester, Langegger, & Raville, 2017; Ellis, Kasper, & Cicero, 2018; McNeil et al., 2020). Lastly, PSU among PWUO could also be driven by substance use availability in the illicit drug supply. For example, the reduced availability of heroin in 2000 in Australia was associated with a decrease in the number of people who injected heroin and an increase in amphetamine injecting among them (Day, Degenhardt, & Hall, 2006). Regardless of the motivations behind engaging in PSU, our findings are in line with the existing evidence suggesting PSU among PWUO to be associated with several adverse mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., major depressive disorders, PTSD, risky sexual practices) in comparison with those who use few or no substances other than opioids (Connor et al., 2014; Crummy et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2012; Timko et al., 2018; Trenz et al., 2013; Witkiewitz & Vowles, 2018).

Our findings are of particular importance in the context of the ongoing opioid epidemic in the US and Canada, where research studies are often “opioid-centric” and may “miss the forest for the trees” by viewing OUD in a silo and excluding people with several high-frequency uses of multiple substances (Cicero et al., 2020). Policies aimed at tackling the opioid epidemic are also often disproportionately focused on the effectiveness of and access to OUD treatment (e.g., various OAT and antagonist therapies), opioid-overdose prevention (e.g., take-home naloxone kits, fentanyl drug checking services), and preventing access to non-medical POs (e.g., prescription drug monitoring) (Cicero et al., 2020; Finley et al., 2017; Kerr, 2019; McDonald & Strang, 2016; Tupper, McCrae, Garber, Lysyshyn, & Wood, 2018). This exclusive focus on PWUO and a single drug class may be justified by the fact that the drugs of choice among most PWUO are arguably natural (e.g., heroin and its derivatives) or synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl and its analogues) (Gryczynski et al., 2019; Kanouse & Compton, 2015; Karamouzian et al., 2020; Ostling et al., 2018). While continued support of these life-saving interventions is essential, our findings suggest that the extent of interventions’ effectiveness for certain subpopulations of PWUO (e.g., those who primarily use stimulants, have concurrent alcohol use disorder, or benzodiazepine use disorder as well as people using other substances while on OAT) might be limited. Recognizing these complexities and considering them in developing care packages for PWUO are essential in addressing the unique needs of these particular subpopulations. These heterogeneities are not just reflected in PWUO’s individual- and structural-level risk factors, but also adverse health outcomes (e.g., fatal and non-fatal OD). These considerable diversities should be reflected in addiction research which often focuses on mono-substance use practices as well as people’s continuum of care in the healthcare system. Implementing policies and practices that are not client-centered, put all PWUO into a single box, and simplify their substance use practices by focusing on their primary drug of choice/use, fail to acknowledge the specific needs and risks of different subgroups among PWUO and may be of limited success.

Predictors of membership in different PSU classes varied significantly across different studies. Among studies that did assess these predictors, membership in higher intensity or frequency of PSU was positively associated with a range of individual- (e.g., sharing needles, frequent IDU, high-risk sexual behaviours), and socio-structural-level exposures (e.g., history of incarceration, homelessness, hospitalization). Study findings regarding the sociodemographic predictors of class membership, however, were relatively inconsistent. While these assessments are informative in characterizing the negative or positive predictors of PSU classes, these findings need to be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First and foremost, PSU operationalization and the proportion of classes identified, varied significantly across the studies. For example, studies used several approaches to measuring patterns of substance use and included an array of different substances from tobacco to fentanyl. Assessments were rarely based on validated metrics and mainly according to arbitrary self-reported measures in the past few days, weeks, months, lifetime, or a combination of several different timelines. Moreover, several studies included multiple indicators of a single type of substance (e.g., frequency, length, and route of use for a certain substance). Additionally, some studies’ identification of various classes of PSU was informed by inclusion of sociodemographic or mental-health-related outcome indicators. These heterogeneities were often reflected in the final class solutions and led to challenges in summarizing the evidence or comparing classes across individual studies. Second, most studies assessed cross-sectional associations between particular behavioural characteristics of the participants with PSU classes, which could raise concerns about temporality bias and establishment of causality. Lastly, several studies did not assess these associations and reported their final class solutions in a merely descriptive fashion and, therefore, provided a limited picture of potential predictors of class membership in their analysis.

Limitations

While our systematic review was methodologically rigorous and comprehensive, it is subject to certain limitations, primarily due to the methodological shortcomings of the included individual studies. First, while all studies included PWUO, the sampling framework, sociodemographic, and behavioural characteristics of the participants were heterogeneous. Second, studies operationalization of PSU patterns varied across the studies and made it challenging to make direct comparisons and estimate pooled effect measures. We were also unable to compare studies that used various outcome indicators in terms of their findings. Moreover, although PSU classes with high frequency of benzodiazepines and POs were not identified as primary classes in the analysis, it is important to note that subgroups of people who frequently use benzodiazepines and POs do exist among PWUO and their specific needs should be recognized in clinical practice and intervention developments. Third, we only focused on latent analytical approaches and did not include studies that used traditional clustering approaches (e.g., k-means, hierarchical cluster analysis) in our review. This decision was informed by latent class analytical approaches’ superior statistical robustness and flexibility to cluster-based models, due to their probabilistic model-based nature (DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2006). Moreover, making methodological comparisons between the studies and summarizing the evidence from two distinct statistical approaches would have been challenging. Fourth, most of the participants in the studies were male, White, and from North America, limiting the findings’ generalizability to other contexts where OUD is a significant public health concern (e.g., West and Southeast Asia). Additionally, given the inconsistencies in classifying race/ethnicities across the studies, we could not provide more detailed assessments about the association of race/ethnicity with PSU classes. Lastly, the findings of these studies should be interpreted with an eye to the rapidly changing illicit opioid supply across the world, in North America in particular. Future studies on measuring PSU among PWUO would benefit from looking at how PSU classes may have evolved in the context of an increasingly toxic drug supply where PWUO may be knowingly or accidentally exposed to synthetic opioids. Despite these methodological limitations, most studies were robust, had a large sample size, and were of reasonable quality. Overall, our systematic review provides an overview of various classes and predictors of PSU patterns among PWUO and helps inform the clinical and public health interventions aimed at addressing the opioid epidemic.

Methodological issues

Our review shows that using latent class and person-centered approaches to identifying distinct PSU patterns among various subgroups of PWUO is useful and informative. However, our quality assessment of the studies identified several areas for improvement for future studies that aim to apply this method to subpopulations of people who use drugs. Most studies used unvalidated or unstandardized measurement approaches for substance use indicators. Another important limitation of PSU analyses across most studies was overlooking tobacco use in their PSU analyses, despite the significant frequency and association of tobacco smoking and opioid use among PWUO (Akerman et al., 2015; John et al., 2019; Rajabi, Dehghani, Shojaei, Farjam, & Motevalian, 2019). Several studies also did not report how missing data were handled in their study. Further clarity and consistency about all possible models’ fit indices and final model selection procedures are essential in creating reproducible, reliable, and comparable results. Moreover, the notable limitations about sex- and gender-based reporting and analytical approaches observed across the studies (e.g., not reporting data on participants’ sex or gender, not conducting sex- or gender-stratified analyses, and confusing sex with gender) further highlight an important knowledge gap (Greaves, 2020), as well as the need for a systematic integration and exploration of sex and gender in future research on latent PSU patterns (Heidari, Babor, De Castro, Tort, & Curno, 2016). Some of the above-mentioned shortcomings have been repeatedly reported in previous reviews aimed at identifying clusters or classes of substance use (Halladay et al., 2020; Petersen et al., 2019; Tomczyk et al., 2016; Van De Schoot et al., 2017) and could be addressed by following the existing reporting guidelines for these types of analyses (Petersen et al., 2019; Van De Schoot et al., 2017).

Conclusions

Our systematic review summarized the evidence that applied person-centered approaches to the classification of PSU among PWUO. While heroin and its derivatives were the most common class, we found that PSU was the norm, not the exception. However, the heterogeneities among PSU classes of PWUO were considerable. Our findings call for further investments and research in developing treatments and interventions that go beyond focusing on the use of opioids among this population and apply a holistic and comprehensive approach to providing care for PWUO. Applying methodologically rigorous and transparent techniques as well as using standardized metrics for evaluating the frequency and severity of substance use patterns are required to allow direct comparisons across the studies’ findings and improve their generalizability.