Abstract

This study assesses how different forms of abuse and neglect are associated with juvenile offending, with specific emphasis on whether youth commit offenses analogous to the illicit parental behaviors to which they were exposed. Using statewide child welfare system data linked with juvenile offending records, we assess rates and types of offending among a cohort of youth exposed to child maltreatment, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect (N=7,787). Findings suggest that the maltreatment-delinquency link is better characterized as a general rather than a specific cycle of violence, though sex abuse victims tend to specialize in sex offending. Youth exposed to physical abuse, moral neglect, and parent incarceration offend at high rates overall and should be prioritized for prevention and treatment services.

Youth involved with the child welfare system (hereafter, CWS), including youth in foster care, experience heightened risk for delinquent behavior (Fagan, 2005) and juvenile justice contact (Goodkind et al., 2013; Mersky & Reynolds, 2007). An estimated 45% to 70% of youth involved with the juvenile justice system (hereafter, JJS) have current or prior CWS involvement (Herz et al., 2019), a population typically referred to as crossover or dual system youth. Because the CWS is primarily tasked with responding to child maltreatment, associations between CWS and JJS involvement are thought to reflect, at least in part, criminogenic effects of maltreatment. Yet, there is significant discordance in research findings about the nature of these associations. Scholars typically emphasize social learning theory (Sutherland, 1947) or the related cycle of violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989) as explanatory frameworks, particularly for associations between violence exposure and violent delinquent offenses. Nonetheless, several studies have found that neglect or other non-physical forms of maltreatment are equally strong predictors of violent offending (Mersky & Reynolds, 2007; Smith et al., 2005), and that violence exposure is associated with enhanced risk for all types of offending, rather than increasing risk for violent offending alone (Steketee et al., 2021). In sum, there are unresolved questions about how child maltreatment and delinquency are connected, and specifically which types of maltreatment present the greatest risk for juvenile offending. These questions have both theoretical applications regarding the etiology of delinquent behavior and practical implications regarding how the CWS should target its limited resources to reduce crossover into the JJS among abused and neglected youth. The present study analyzed rates and types of JJS involvement among Pennsylvania (USA) youth following a CWS-confirmed exposure to abuse or neglect (N=7,787).

Background

Maltreatment Identified by the Child Welfare System

Approximately 75% of confirmed child maltreatment cases in the U.S. involve neglect, and over half involve neglect alone (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021). Physical and sexual abuse, respectively, account for about 16% and 10% of CWS cases nationally, with female children more likely to experience sexual abuse than male children. Many environments classified as neglect involve illicit (or, crime-related) parental behavior. For example, parental substance abuse, typically involving illegal drugs, is a factor in 40% to 80% of CWS cases (Palmer et al., 2022). In addition, law enforcement often reports to the CWS when they raid homes for drug-related criminal activity or respond to domestic violence calls, and find children present (Rebbe et al., 2021). However, in most existing datasets, all manifestations of neglect fall under a single category. Thus, research has not been able to ascertain how or in what ways victims of neglect engage in delinquency and whether those delinquent offenses are analogous to behaviors witnessed in the home (Font & Kennedy, 2022).

Mechanisms Linking Child Maltreatment to Delinquency

Social learning perspectives (Sutherland, 1947) and the related cycle of violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989) posit that youth model or imitate behaviors that they have witnessed or experienced directly. When caregivers engage in illicit activity, youth my acquire beliefs and expectancies favorable to those behaviors, even if their parents do not explicitly endorse or enable youth to engage in the illicit behavior themselves. Consequently, such perspectives anticipate that the type of adversity that a youth experiences is directly informative about the types of delinquency in which they are likely to engage— for example, that physical abuse victims will disproportionately engage in violence. We refer to this as analogous offending, wherein offending involves conduct similar to that which they were exposed in their homes.

There are two approaches that have commonly been used to study analogous offending. First, studies have compared individuals with and without a specific exposure and assessed whether the exposed group had a higher rate of analogous offending (e.g., Fagan, 2005). These studies address whether victims of physical abuse commit more violent crimes than non-victims. More rigorous versions of this approach compare violent offending for victims of physical abuse to victims of other types of harm, such as sexual abuse (e.g., Leach et al., 2016). Overall, this body of work finds conflicting results. For example, physical abuse victims are more likely to commit violent offenses than non-victims (Maas et al., 2008), but not necessarily more than victims of neglect or other types of maltreatment (Mersky & Reynolds, 2007; Smith et al., 2005). Some studies find that sexual abuse victims, particularly male victims, are more likely to commit a sex offense than non-victims (Ogloff et al., 2012), but others do not (Noll, 2021). In addition, for two key contexts of neglect that involve illicit parental behavior—parental substance abuse and domestic violence—there is evidence of specific intergenerational transmission. Miley et al. (2020) found that witnessing household substance abuse was positively associated with drug offending in adolescence, and it is well-established that children whose parents abuse drugs are more likely to use substances themselves (Rossow et al., 2016).

Although informative, these studies do not rule out the possibility that particular types of maltreatment lead to higher rates of offending generally— for example, that youth exposed to physical abuse are at greater risk of engaging in all types of offenses, including but not limited to violent crime. Studies that do examine this possibility tend to support the expectation of elevated rates of general offending for certain maltreatment types. For example, children exposed to domestic violence commit more violent crime and more general crime than children without exposure to domestic violence (Steketee et al., 2021). Moreover, many studies do not account for the possible confounding effects of neglect, which may result in an overstatement of typespecific associations between an exposure and analogous offending (Font & Kennedy, 2022).

A second type of study of analogous offending considers whether victims of particular maltreatment types are more likely to commit analogous offenses than non-analogous offenses (e.g., Felson & Lane, 2009). Often these are studies of offenders, where the question pertains to whether victims of physical abuse, for example, commit a greater share of violent offenses than would be expected if the type of crime were independent of the victimization type. Broadly, these studies find evidence of specialization in analogous offending for both physical and sexual abuse (Asscher et al., 2015; DeLisi et al., 2014; Van der Put et al., 2015). These studies are informative about offending behavior for those who offend, but they tell us little about the propensity for victims to become offenders, and how this differs across types of exposures.

In contrast to research assessing whether specific forms of maltreatment exposure are linked to specific forms of delinquency, other frameworks suggest that maltreatment will increase risk for offending generally. That is, a given form of maltreatment may be associated with non-analogous offending (offending that involves conduct unrelated to their victimization experiences, such as theft offenses for victims of sexual abuse) or generalized offending (both analogous and non-analogous offending). Child maltreatment induces stress and heightens reactivity to both negative and neutral stimuli (Cook et al., 2012), thus weakening youth’s ability to manage impulsive behavior. Thus, when presented with provocation or criminal opportunity, such as an insult by a peer or an offer of drugs, maltreated youth may be more susceptible. In this scenario, the nature of the delinquent acts would be unrelated to their proximal maltreatment experiences. Of note, this mechanism linking maltreatment and delinquency should apply similarly to maltreatment that involves illicit parental behavior and maltreatment that does not involve illicit parental behavior (e.g., inadequate supervision and unmet physical needs). Indeed, researchers examining Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs—typically defined as abuse, neglect, household substance use, household mental illness, parental separation, and parental incarceration—find that ACEs disrupt personality and social development, which may lead to impulsiveness, reactive aggression, and delinquency (Perez et al., 2018). This work emphasizes the cumulative impact of ACE exposure (Baglivio et al., 2021; Baglivio & Wolff, 2021), as a higher numbers of ACEs, likely indicative of greater stress, is associated with both any offending and offense-specific recidivism (Craig et al., 2020; DeLisi et al., 2017).

Homes where maltreatment occurs tend to involve lower parental monitoring (Robertson et al., 2008) and more strained parent-child relationships (Baer & Martinez, 2006). Youth in these environments may not only have more opportunities to offend, but may also feel less constrained by potential informal sanctions, such as parental disapproval. Consistent with the assertion that maltreatment may lead to generalized offending, a robust literature has found that victims of sexual abuse are more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol (Fletcher, 2021), which may lead to JJS contact for drug possession or crimes committed under the influence of substances.

Summary and Current Study

Research has repeatedly affirmed that child maltreatment exposure is associated with higher rates of delinquency and JJS involvement (Maas et al., 2008). However, research remains unclear about how offending patterns differ by type of maltreatment, and most studies have either failed to consider neglect entirely or have been limited to an aggregate measure of neglect that provides little information about the underlying context. We leveraged detailed information on children’s abuse and neglect exposures to examine whether juvenile offending rates and types of offenses differ based on particular types of maltreatment experiences. First, we assessed whether maltreatment that involves illicit parental behavior (i.e., behavior for which there is an analogous delinquent offense) is associated with higher rates of juvenile offending that other forms of maltreatment. Following a broad conceptualization of social learning theory (Sutherland, 1947), we expected that maltreatment involving illicit parental behavior would be associated with higher rates of offending than maltreatment not involving illicit parental behavior, across all offense categories. Second, we assessed the specificity of social learning or the “cycle of violence” (Widom, 1989) by investigating whether children exposed to a particular illicit parental behavior perpetrate the analogous form of delinquency at higher rates than children who do not have that exposure. For example, are youth exposed to parental substance use charged with drug offenses at higher rates than youth exposed to other forms of maltreatment? Last, we considered whether particular types of maltreatment exposures lead to delinquency “specialization.” For example, are victims of physical abuse more likely to engage in violent offenses alone or are they more likely to engage in all forms of delinquency (i.e., generalized offending)?

Method

Data

Data for the current study came from two sources.1 The first was CWS cases obtained from the Office of Children, Youth, and Families in the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, which oversees the county-level Children and Youth Services Agencies (CWS records). The second was official records from the Pennsylvania Juvenile Court Judges’ Commission (JJ records). Records from these two sources were linked for the current study to identify children with involvement in both systems using probabilistic matching.2

Due to statewide expunction policies, our data were limited to youth with a substantiated or validated CWS case or who were accepted for CWS services.3 We excluded youth who were involved with the CWS as a perpetrator or parent, and youth who were only involved with the CWS due to behavioral issues (rather than abuse or neglect). We then reduced the sample to include only youth who had reached ages 15 to 18years by the start of 2020 (born 2000–2006) and who had CWS involvement for abuse or neglect between the ages of 9 and 13 years. Juvenile records were identified for all youth with onset of delinquency prior to 2020, and charge information for those youth was available through 2019. Limiting the sample in this way allows for the observation of youth during the portion of adolescence when offending typically occurs.4

Measures

The focal independent variables were CWS-identified maltreatment types, categorized in two ways. First, from all reports for a youth during the study period that were either confirmed for abuse or neglect or resulted in the provision of services, the type(s) of exposures a youth experienced were categorized as either involving illicit parental behavior or not. Illicit parental behaviors identifiable in the maltreatment records were physical abuse, sexual abuse, parent substance abuse, domestic violence, involving/encouraging a child in the commission of a crime (moral neglect), and parent incarceration (non-illicit parental behaviors involved in maltreatment reports were inadequate supervision, parent mental health concern, emotional abuse, no caregiver, inappropriate caregiver, and lack of food, clothing, housing, or medical care.) A binary indicator of illicit parental behavior exposure was equal to 1 if the child experienced any of illicit parental behavior categories, and 0 if they experienced none. Second, we created non-mutually exclusive5 indicators of whether the child was exposed to each of the five types of illicit parental behavior: physical abuse, sexual abuse, substance abuse, domestic violence, and other. All CWS variables were measured dichotomously as ever/never during the study period.6

Juvenile Offending. All JJS charges, regardless of adjudication status, were included in our analyses (arrests and referrals that did not result in charges being filed are not available in our dataset). Although some JJS charges that do not proceed to adjudication are baseless (e.g., false allegations), charges are a more sensitive indicator of delinquent behavior because of the state’s preference for using diversion and deferment to avoid adjudication wherever possible.

We first created a measure of any offending, equal to 1 if the youth was charged through the JJS at any point during the study period, and 0 otherwise. Using all charges to which the youth was subjected during the observation period (across all identified referrals), we then created dichotomous, nonmutually exclusive indicators of whether the youth was charged with each of the following offense categories: (1) violence-related crime, including assaults, violent threats or stalking, and weapons charges; (2) sex crimes, including sexual assaults, possession or dissemination of child pornography, indecent exposure, and pandering, (3) drug and alcohol related crimes, including public intoxication, possession, sales, and driving under the influence, and (4) other crimes, primarily consisting of theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, or criminal mischief. Charges in the “other” offense type category were included in the measure of any offending but were not analyzed as their own offending type because most of these charges were incurred during the commission of another crime for which the youth is also charged.

Lastly, we created a four-category measure of offending specialization for each of the illicit parental behavior exposure types (physical abuse, sex abuse, substance abuse, and domestic violence), which were categorical outcomes equal to 0 (reference category) if the youth had no JJS charges, 1 for specialized offending (the youth engaged in only analogous offending), 2 for nonanalogous offending (the youth engaged in only offending that was not analogous to their exposure), and 3 for generalized offending (the youth engaged in both analogous and non-analogous offending).

Covariates. All models included the following statistical controls, each of which are associated with juvenile offending (Lee & Villagrana, 2015): race/ ethnicity (non-Hispanic White [reference group], non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other race/ethnicity), gender (male=0 [reference group], female=1), years of age at time of CWS contact (9–13) and a binary indicator or whether the youth had previously been removed from their home were included as covariates.

Analytic Strategy

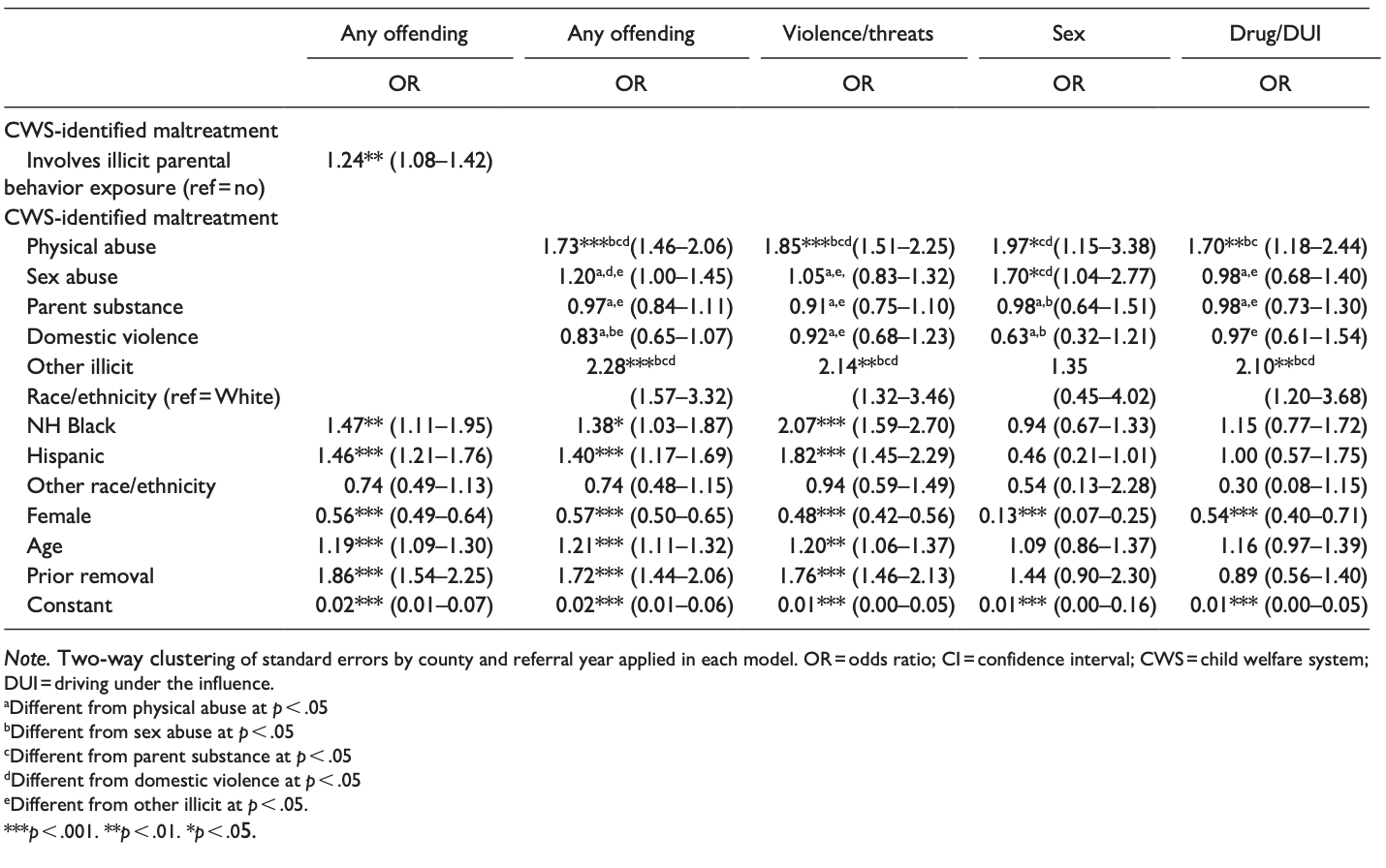

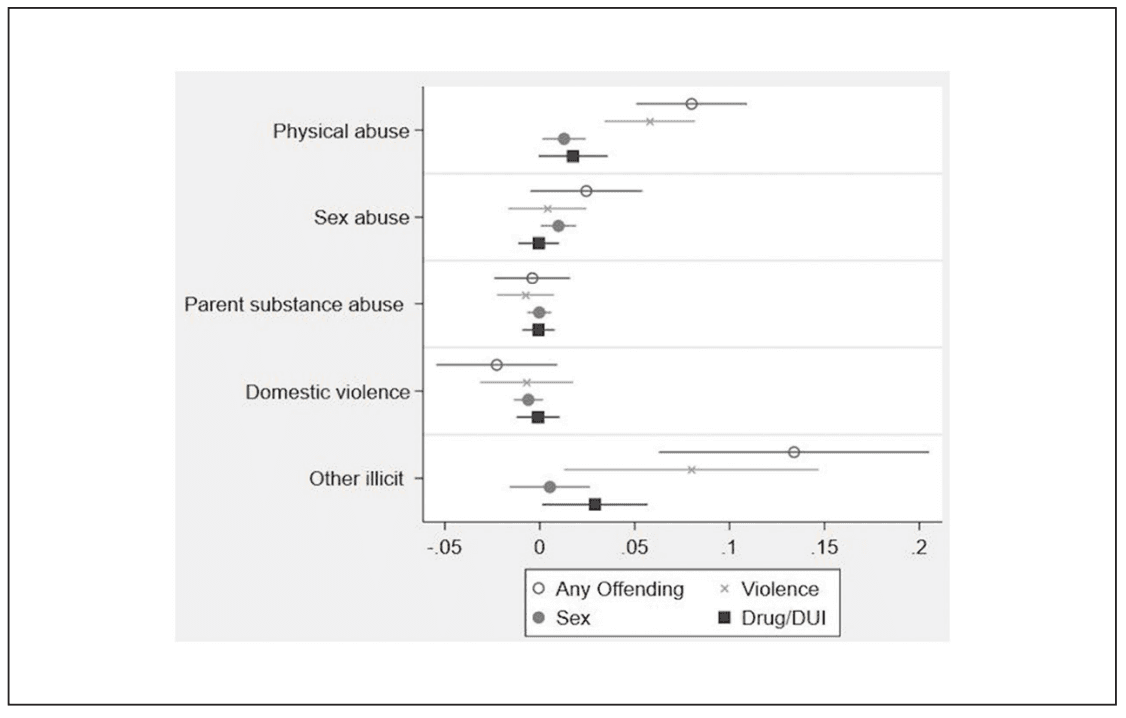

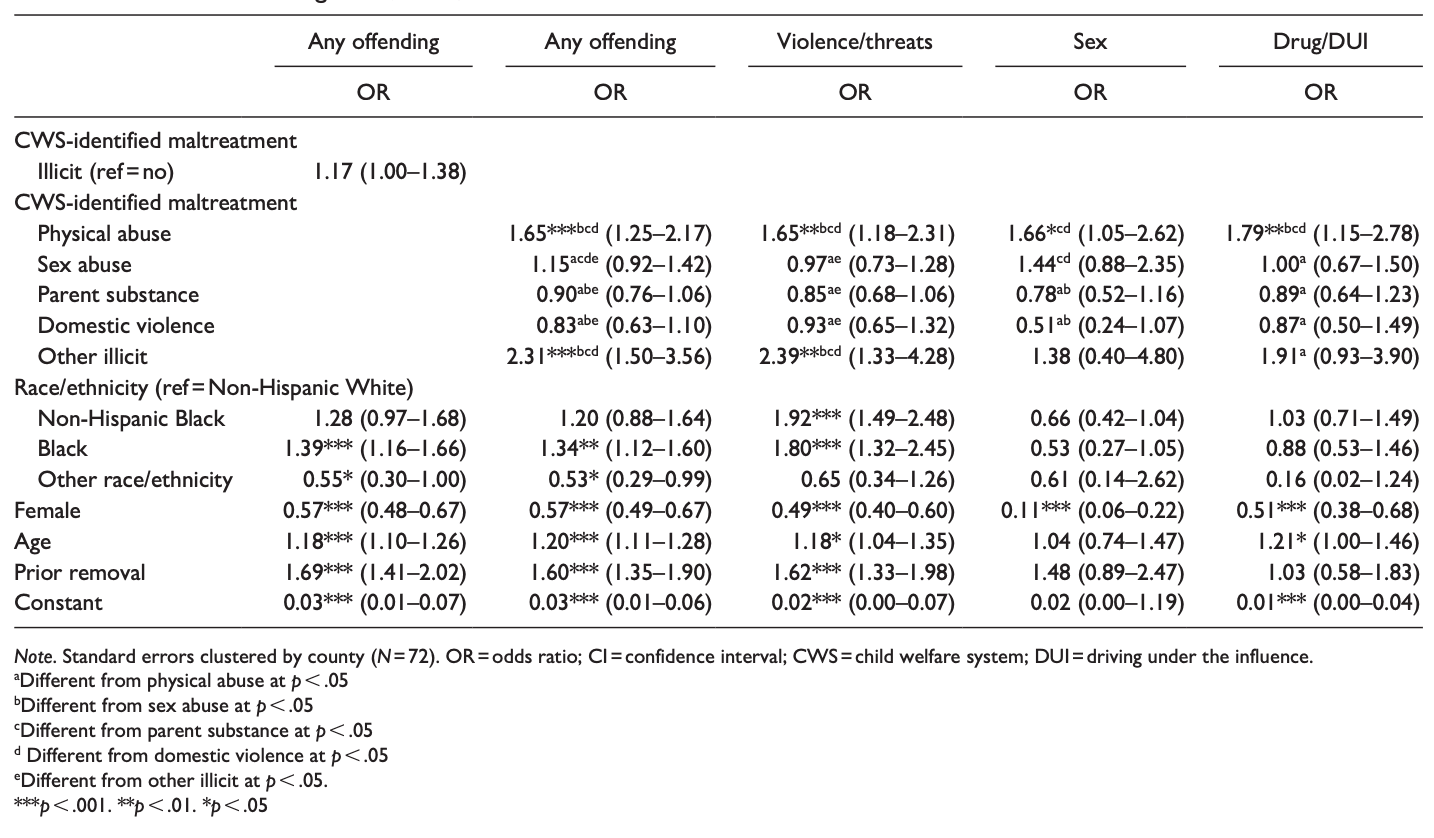

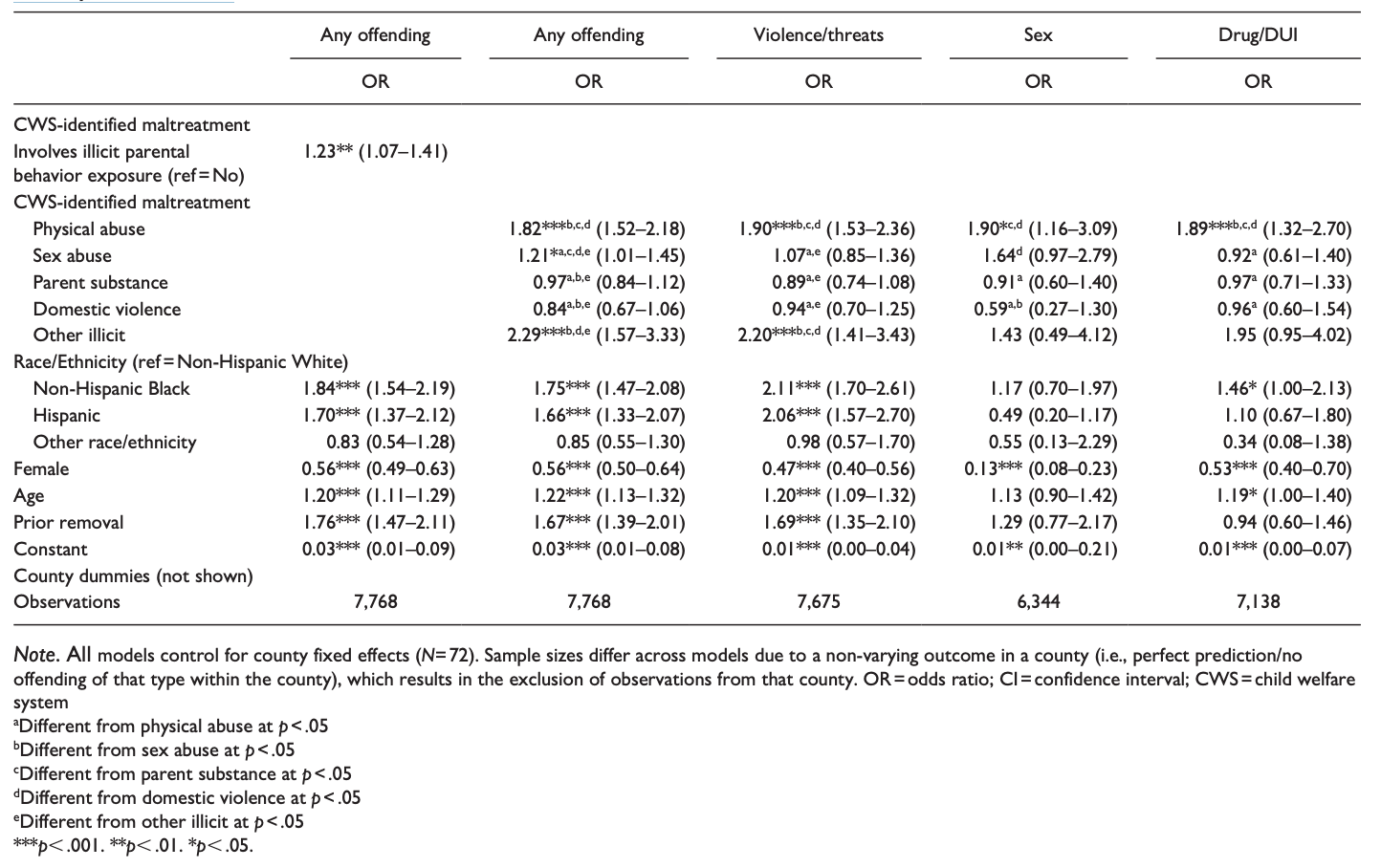

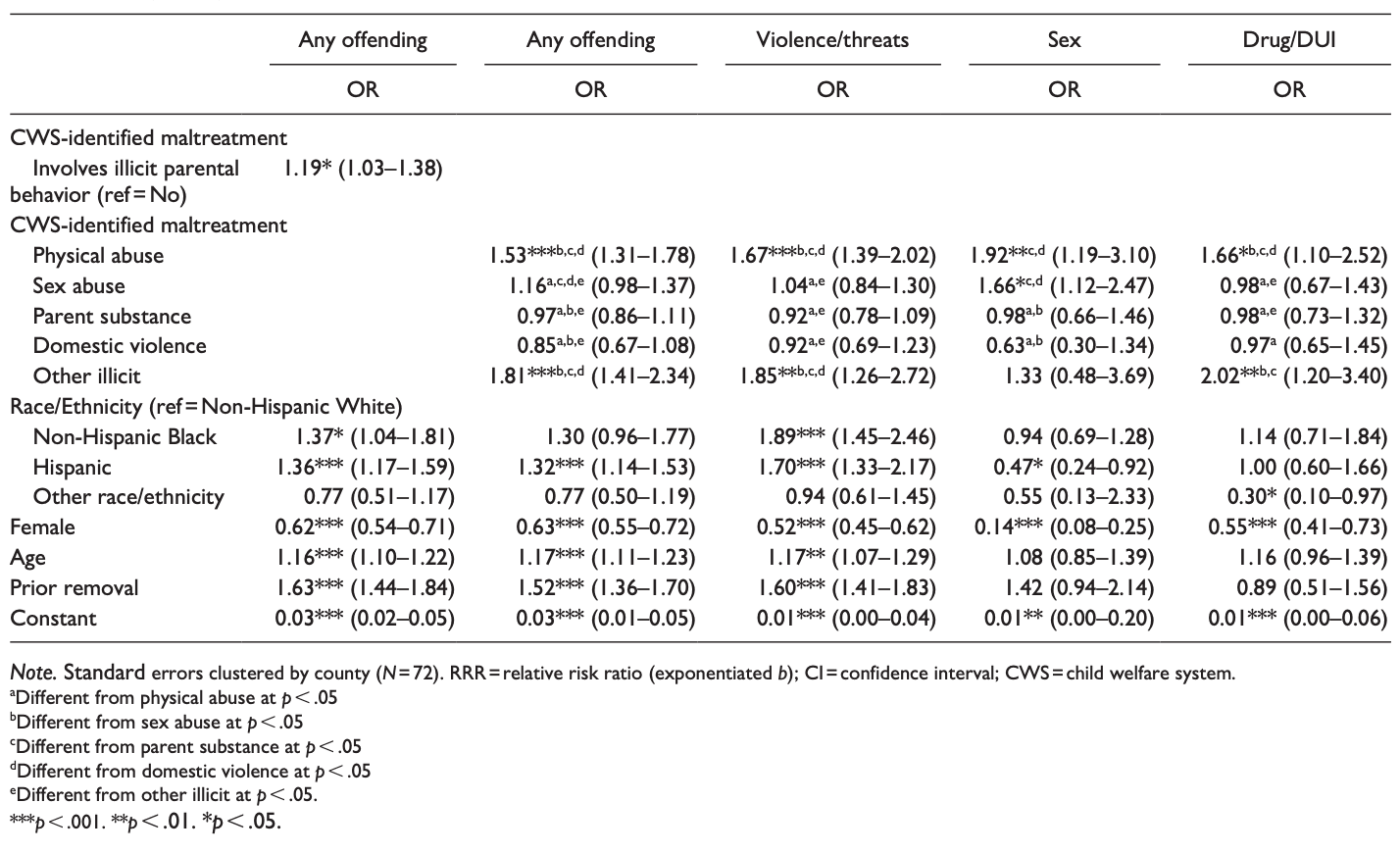

To answer our first research question (Is exposure to maltreatment that constitutes illicit parental behavior [relative to maltreatment that does not constitute exposure to illicit parental behavior] positively associated with youth offending?), we estimated a logistic regression model predicting any JJS offending as a function of whether the youth’s CWS-identified maltreatment involved any illicit parental behavior exposure (Table 2). Our second research question (Is exposure to particular forms of maltreatment constituting illicit parental behavior associated with increased likelihood of the youth perpetrating analogous forms of delinquency?) was addressed by regressing each of the JJS offending types on the types of illicit parental maltreatment exposure (e.g., physical abuse, domestic violence; Table 2).7 Due to the binary nature of the dependent variable, we plotted the marginal effects of each exposure on any offending and offending types (see Figure 1). This strategy allowed us to summarize the independent variables’ effects on the outcomes in terms of the model’s predictions while avoiding scaling issues (see Mize, 2019).

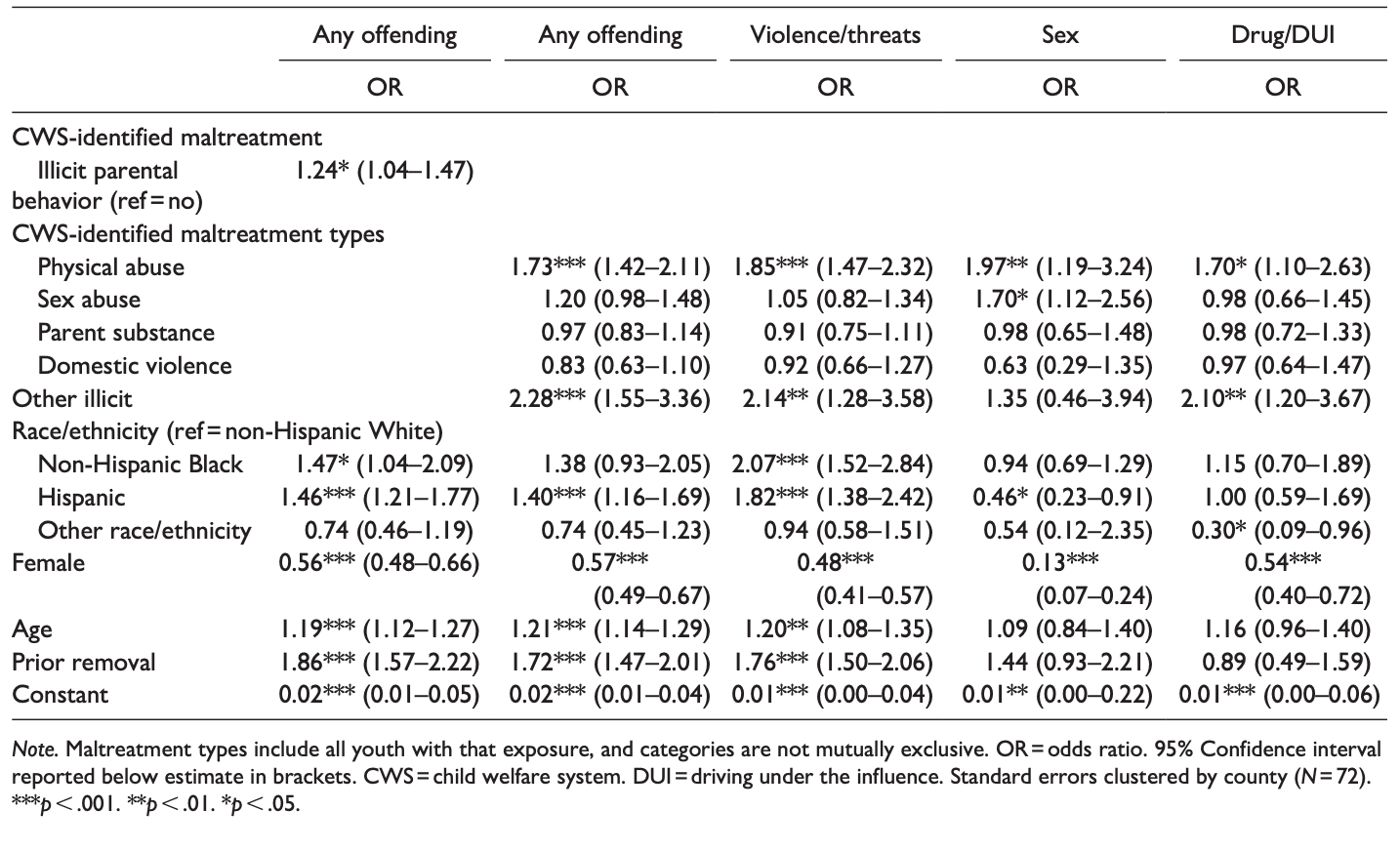

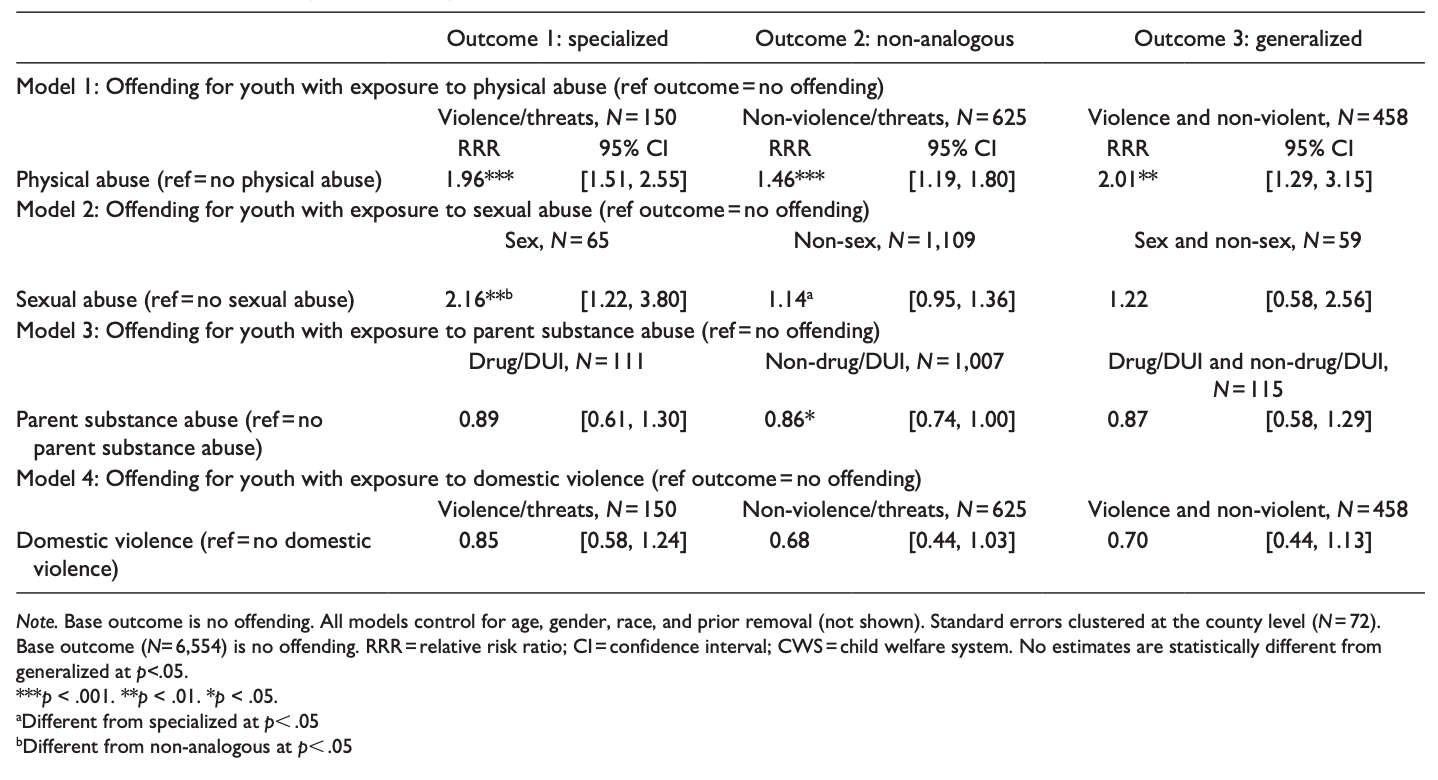

Our final research question (Do youth exposed to a particular form of maltreatment constituting illicit parental behavior specialize; are they are more likely to commit analogous offenses than non-analogous or generalized offenses?) was addressed using multinomial logistic regression models predicting the odds of analogous, non-analogous, and generalized offending relative to no offending (base outcome; see Table 3). The first specialization model examined offending patterns for youth with physical abuse exposure (versus without physical abuse exposure), where the analogous offense was violence/threats. The second model examined offending by sex abuse exposure (analogous offense = sex offending). The third model examined offending by parent substance abuse exposure (analogous offense = drug/DUI), and the fourth examined offending by domestic violence exposure (analogous offense = violence/threats). “Other” illicit parental behavior exposure was not examined in the specialization models due to small sample size (see Table 1) and because this category did not contain a clear analog to a specific offending type. In all models, standard errors were clustered at the county level.8,9

Figure 1. Marginal effects of CWS-identified maltreatment types for any offending and types of offending based on the logistic regressions presented in Table 2 (N=7,787).

Note. 95% Confidence intervals indicated by lines surrounding the estimates. Marginal effects refer to changes in an explanatory variable and its effect on the predicted probability of an outcome. Statistical tests of the marginal effects indicated that for any offending, violence/ threats, and drugs/DUI, the effects of physical abuse and other illicit each differed from the effects of sex abuse, parent substance abuse, and domestic violence. For sex offending, physical abuse and sex abuse differed from parent substance abuse and domestic violence.

Results

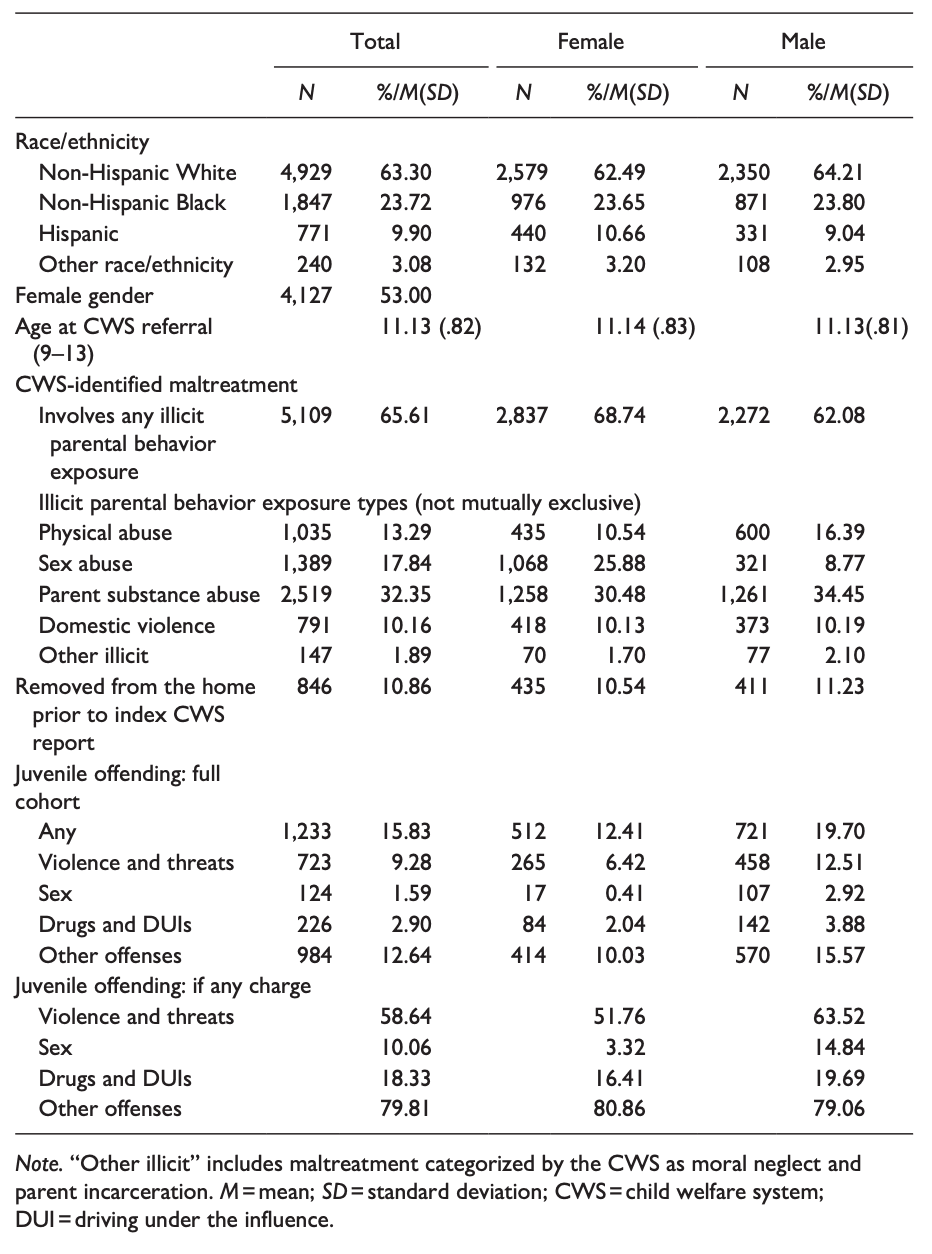

Nearly two-thirds of youth (65.61%) had CWS-identified maltreatment involving exposure to any form of illicit parental behavior; 34.39% had no known exposure to illicit parental behavior (see Table 1). Parent substance abuse was the most common form of illicit parental behavior exposure (experienced by 32.35% of the cohort), followed by sex abuse (17.84%), physical abuse (13.29%), domestic violence (10.16%), and “other” (1.89%). Females were more likely than males to have illicit parental behavior exposure (68.74% versus 62.08%), reflecting a higher rate of sex abuse exposure among females (25.88%) versus males (8.77%).

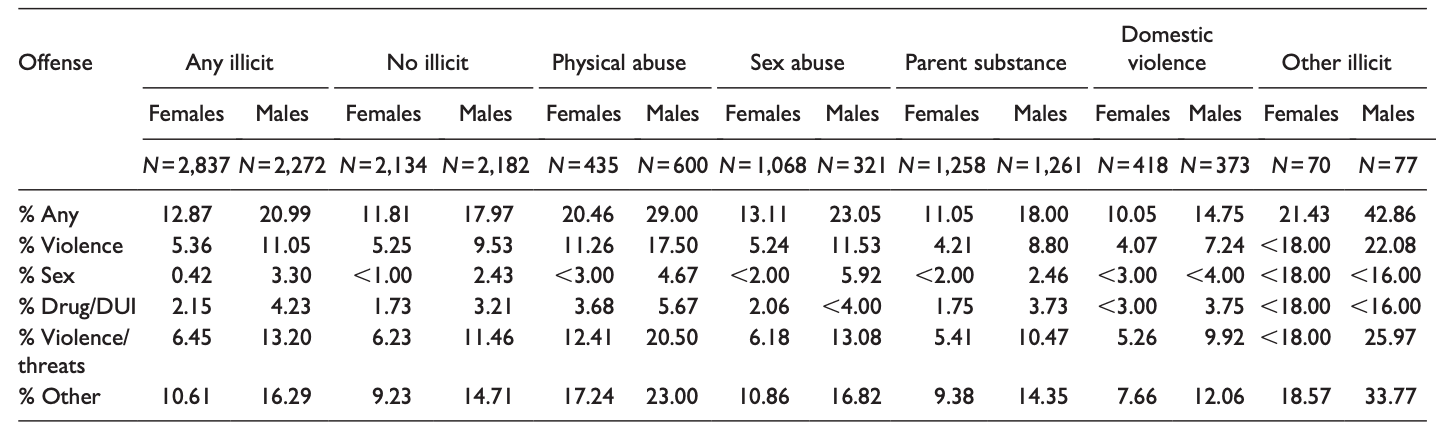

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Cohort of Youth With CWS-identified Maltreatment Between 2013 and 2016, N=7,787.

Turning to juvenile offending, 15.83% of the cohort had one or more JJS charge, including 12.41% of females and 19.70% of males. Offending involving violence or threatening behavior was most common (total cohort: 9.28%, JJS-involved cohort: 58.64%), mostly reflective of violent acts such as assaults (total: 7.81%, JJS-involved: 49.31%). Less common charge types involved drugs or alcohol (2.90%), sex offenses (1.59%), disorderly conduct or reckless behavior (6.46%), financial crimes such as theft (5.12%), ordinance or condition violations (4.31%), and criminal mischief such as vandalism (3.78%). Overall, 12.64% of the cohort (JJS-involved: 79.81%) had at least one charge that fell under the “other” offending category, which were offenses without an analogous form of illicit parental behavior (disorderly conduct, condition violations, financial, criminal mischief, and traffic/ transfer).

Juvenile Offending by Maltreatment Type

Table 2 presents logistic regression models predicting any JJS offending. In model 1, we found that illicit parental behavior exposure (relative to none) was associated with a 1.24 factor increase in the odds of any offending (p<.05).

Models 2 through 5 considered how specific types of illicit behavior exposure are associated with offending. We found that physical abuse was associated with all types of offending measured (any, violence/threats, drugs/DUIs, sex), with similar odds ratios across models (ORs ranging from 1.70 to 1.97, all p<.05). Exposure to “other” illicit parental behaviors was also associated with higher odds of any offending, violence/threats, and drug/DUI offending (ORs ranging from 2.08 to 2.28, all p<.01), but not sex offending. Sexual abuse was associated with increased odds of sex offending only (OR=1.70, p<.05). Parental substance use and domestic violence exposure were not associated with offending in any of the models. Post-hoc estimation and testing of marginal effects indicated that the associations of physical abuse and “other” illicit parental behavior with any offending, violence/threats, and drug/DUI offending were significantly different from the other illicit parent behavior types but not from each other (Figure 1). For sex offending, the marginal effects for physical abuse and sex abuse were significantly different than the marginal effects for parent substance abuse and domestic violence.

Offending Specialization

Table 3 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression models assessing offending specialization. Model 1 predicted patterns of offending for youth with exposure to physical abuse (relative to no exposure to physical abuse). Relative to no offending, physical abuse was positively associated with violent offending (specialization; RRR=1.96), non-violent offending (non-analogous; RRR=1.46), and both violent and nonviolent offending (generalized offending; RRR=2.01). The coefficients for physical abuse were not significantly different for generalized, specialized, and non-violent offending. Model 2 predicted patterns of offending for youth with exposure to sex abuse. Relative to no offending, sex abuse was positively associated with sex offending (RRR=2.16, p<.01) but not associated with non-sex (non-analogous) nor generalized offending. The coefficients for sex abuse were significantly different for sex offending and non-sex offending. Consistent with the models in Table 2, Models 3 and 4 found no evidence of association between parent substance use (Model 3) or domestic violence exposure (Model 4) and any form of offending (analogous, non-analogous, or generalized).

Table 2. Logistic Regressions Predicting Any Offending and Type of Offending by Type of CWS-identified Maltreatment, N=7,787.

Table 3. Multinomial Logistic Regression Models Predicting Specialized, Non-Analogous, and Generalized Offending by CWSIidentified Maltreatment Exposure to Physical Abuse, Sex Abuse, Parent Substance Abuse, and Domestic Violence.

Discussion

This study addressed a crucial gap in the literature concerning how CWS contact relates to JJS offending, particularly regarding whether victims of child abuse and neglect perpetrate offenses analogous to the illicit parental behaviors to which they were exposed. Three key findings emerged. First, youth with exposure to any form of illicit parental behavior had higher rates of any offending than youth exposed to maltreatment that lacked an analogous criminal act, such as inadequate supervision or emotional abuse. This finding is supportive of our expectation that youth may learn favorable norms or beliefs about illicit behaviors witnessed in the home, engendering increased risk of JJS offending. However, these patterns were largely driven by greater offending by physically-abused youth, whose odds of offending were 70% higher than maltreated youth without physical abuse exposure. This result is consistent with prior research which finds that physical abuse is predictive of elevated rates of any form of offending (Van der Put et al., 2015). The “other” illicit parental behavior category, primarily comprised of parents who involved their children in morally corrupting behavior (e.g., providing them with drugs or alcohol), was relatively infrequent, but where present, was also associated with high rates of offending. Although social learning of beliefs conducive to delinquency does not require explicit encouragement of criminal behavior by parents, it is not surprising that youth whose parents enable or tolerate high-risk behavior exhibit higher levels of offending. To optimize delinquency prevention efforts, it may be most efficient to target youth with these two types of exposures.

Second, we found no evidence that the most common illicit parental behaviors typically included in neglect (i.e., substance abuse and domestic violence) were independently associated with increased offending. Analyses of specific JJS offending types revealed that exposure to parental substance abuse was not positively associated with drug offending, and exposure to domestic violence was not associated with violence and threats. These findings contrast with the expectations of the cycle of violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989) and broader literature indicating high delinquency rates among youth experiencing neglect (Mersky & Reynolds, 2007; Smith et al., 2005). Possible explanations for these discrepancies include variations in study time frames (previous studies used data from a period marked by higher juvenile and violent crime rates) or differences in state-defined thresholds for neglect or the response to neglect.

Third, despite higher levels of offending among youth exposed to illicit parental behaviors overall, evidence of specialization in offending analogous to the illicit behavior exposure was relatively weak. Although physical abuse was positively associated with violence and threats, it was also positively associated with all other types of offending. For example, compared to no physical abuse exposure, experiencing physical abuse was associated with about 1.9 times higher odds of violent offending and 1.7 times higher odds of drug-related offending—statistically equivalent coefficients. In our test of specialization, physical abuse victims were not more likely to commit only violent crimes than only non-violent crimes (or to be generalized offenders). These results contradict research which finds evidence of specialization (analogous offending) for youth with exposure to physical abuse (Asscher et al., 2015; Van der Put et al., 2015), which may be because many of these studies examine populations of only offenders. In short, it does not appear that social learning in the form of imitating specific behaviors is the primary mechanism underlying this maltreatment-delinquency link.

Sex abuse was the exception to this pattern. Victims of sex abuse were more likely to engage in sex offending but not more likely to engage in any other type of offending, and their offending was more likely to only involve sex offenses (vs. non-sex offenses or generalized offending). This finding contradicts previous research reporting that sex offending was not disproportionately common among victims of sexual abuse (Noll, 2021). However, our results align with other studies, primarily retrospective in nature, that demonstrate an association between sex abuse and subsequent sex offending (DeLisi et al., 2014; Levenson et al., 2017). Further, our findings align with research indicating this association for males (Van der Put et al., 2015), as most sex offenses in our study were committed by males (see Table A1). Aside from social learning mechanisms, it is plausible that sex abuse contributes to insecure attachments and intimacy struggles, which are recognized as risk factors for sex offending (Grady et al., 2016).

Experiencing maltreatment may contribute to trauma reactions or distress, which results in offending through maladaptive behavioral problems or mental health disorders (Perez et al., 2018). Some forms of maltreatment may be more likely than others to inflict a high level of distress (e.g., physical abuse may be more likely than parent substance use to induce trauma reactions). It is also plausible that certain maltreatment types are more likely to weaken social bonds, lead to more strained parent-child relationships, or correlate with low levels of parental monitoring (Robertson et al., 2008), which may translate to increased opportunity for juvenile delinquency. Overall, our results align with frameworks which suggest that certain types of maltreatment increases risk for offending more generally.

In terms of policy recommendations, our study implies that delinquency prevention funding should target children with physical abuse histories, who were the most likely to be charged with JJS offending in our study. Explorations into the effectiveness of interventions designed to enhance prosocial bonds and/or augment adult supervision, exemplified by approaches like Child–Parent Relationship Therapy (CPRT; Bratton et al., 2010), as well as interventions focused on mitigating harsh parental behaviors and fortifying the family ecology among CPS-involved families, as seen in Multisystemic Therapy for Child Abuse & Neglect (MSTCAN; Swenson et al., 2010) warrant empirical investigation for their potential in preventing the initiation of delinquency following experiences of physical abuse. Additionally, the assessment of interventions that enhance coping skills, such as those employed in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Berk et al., 2013), should be conducted to determine their efficacy in preventing the onset of delinquent behavior. Once offending has onset, there is an opportunity to couple delinquency interventions with trauma-relevant services. Increasingly, JJS agencies are engaging in trauma or ACEs related screening to identify children whose offending behavior may stem from maltreatment histories or who may require additional rehabilitative services.

Our findings also imply that states should incentivize the use of systemwide, trauma-informed care (TIC) practices in both child welfare and juvenile justice. TIC addresses service provision with the understanding that past trauma affects a youths’ functioning and responses to treatment and punishment, and that stronger efforts at post-investigation screening and assessment, followed by appropriate referrals to trauma-informed, evidence-based treatment are critical to disrupting the relationship between traumatic experiences and future JJS contact (Ford et al., 2016). It has also been suggested that health care funding could be leveraged to provide access to integrated health and TIC for youth who experience abuse (Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2015). On the JJS side, increased use of diversionary practices to address first JJS contact and reduce risk of deeper system involvement for crossover youth might improve youth outcomes. A few evaluations of trauma-informed care within JJ systems indicate that such initiatives are feasible and effective (e.g., Olafson et al., 2018). Our study emphasizes the importance of these programs for maltreated youth at risk of JJS involvement.

Strengths and Limitations

Our reliance on data from CWS records reflecting allegations that were confirmed or resulted in service provision may mean that the maltreatment experienced by youth in our sample is more serious than is typical in the population of maltreated youth (which includes those incidents that are not observed or reported, as well as those that receive an investigation and are determined unfounded). Thus, our findings may not reflect the experiences or outcomes of children experiencing milder forms of maltreatment. However, this limitation is also a strength, as we can be fairly certain that the reported maltreatment type actually occurred. Additionally, due to the time frame of our study, we were only able to include CWS cases that occurred at or after age 9, so abuse or neglect exposure that may have occurred when the child was younger could not be accounted for in these analyses. Even so, compared with maltreatment occurring only early in life, maltreatment during adolescence is a more consistent predictor of adverse outcomes during adolescence and early adulthood, including JJS contact (Goodkind et al., 2013), so our study focuses on the ages in which maltreatment is most likely to lead to delinquency.

JJS charges reflect both actual offending and the actions of law enforcement, and not all delinquent acts have an equal probability of detection by justice systems. There is some evidence that the association between maltreatment and self-reported delinquency is weaker than the association for arrest (Smith & Thornberry, 1995). This may indicate that some of this link is likely a consequence of how systems monitor populations rather than solely reflective of the actual behavior of maltreated youth (Widom et al., 2015). Not all youth in our study were observed until age 18, so justice involvement in adolescence following CWS contact is likely higher than we were able to observe. Although our analyses account for parent incarceration where reported, we do not have information on potential caregiver justice system contact that did not result in incarceration, and incarceration of secondary caregivers is likely underreported because it would be less relevant to a need for CWS intervention (e.g., to arrange alternative care during the incarceration of the primary caregiver). Consequently, illicit behavior of caregivers that resulted in justice involvement but not a CWS case could have influenced delinquency for youth categorized in our study as not being exposed to illicit parent behavior. In addition, our data do not contain youth who were directly filed to (adult) criminal court. Because most youth who are directly filed to adult court commit violent offenses, the percentage of youth identified as violent offenders in our data is likely a slight underrepresentation.10

Children may experience a range of interventions, including out-of-home care, following their exposure to maltreatment that may mitigate, or exacerbate their risk for delinquency. It is beyond the scope of this analysis to explore the influence of post-CWS contact interventions. Moreover, it would be especially challenging to do so in Pennsylvania because foster care is an intervention used for children with serious behavioral concerns (i.e., relating to delinquent behavior) in addition to children exposed to maltreatment. Our data come from one U.S. state (Pennsylvania), so these findings may not generalize nationally. CWS and JJS practices differ across U.S. states, which has implications for whether and how CWS-involved youth become involved with juvenile justice. Finally, we did not provide a comparison to justice-only youth (i.e., youth who were not maltreated), so the extent to which the observed offending patterns in our sample differ from the broader group of justice-involved youth is unclear. However, analyzing a sample of all CWSinvolved youth is useful because it allowed us to assess risk factors of justice involvement related to CWS experiences.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that the link between child maltreatment and delinquency is better characterized as a general rather than a specific cycle of violence. On the whole, maltreatment types did not lead to disproportionate engagement in analogous offending. Youth with exposure to physical abuse and “other” illicit parental behaviors and contexts—moral neglect and parent incarceration—had the highest levels of all offending types and should be prioritized by the CWS as a focus for interventions to prevent delinquent offending behaviors. Specialization in offense types that corresponded to illicit parental behavior exposure was uncommon, aside from specialization in sex offending for victims of sexual abuse. Future work should focus on whether and for whom the mechanisms emphasized by theories based on opportunity or trauma reactions explain the adolescent maltreatment-delinquency link.

Appendices

Table A1. Percentage of Male and Female Youth Charged With Any Offending and Offending Type by CWS-Identified Maltreatment Type.

Table A2. Logistic Regressions Predicting Any Offending and Types of Offending by Type of CWS-Identified Maltreatment for Youth With Confirmed Allegations, N=6,313.

Table A3. Logistic Regressions Predicting Any Offending and Types of Offending by Type of CWS-Identified Maltreatment With County Fixed Effects.

Table A4. Poisson Pseudo-Likelihood Regressions Predicting Any Offending and Types of Offending by Type of CWS-Identified Maltreatment, N=7,787.

Table A5. Logistic Regressions Predicting Any Offending and Types of Offending by Type of CWS-Identified Maltreatment, Standard Errors Clustered by County and Referral Year, N=7,787.