Abstract

This document summarizes the state of juvenile justice in the United States for policymakers.

Introduction

Recent research shows that the human brain continues to develop throughout adolescence, with the pre-frontal cortex – the section of the brain responsible for executive function and complex reasoning – not fully developing until the mid-twenties. Because adolescents’ brains are not fully matured, their decision-making and thought processes differ from those of adults. For example, it is developmentally normative for adolescents to take greater risks and show greater susceptibility to peer influences than adults. These otherwise normal differences can contribute to behaviors that lead to involvement with the juvenile justice system. Beyond developmental influences, additional risk factors associated with youth ending up in the juvenile justice system are cognitive deficits, low school involvement, living in poverty, or being runaway or homeless.

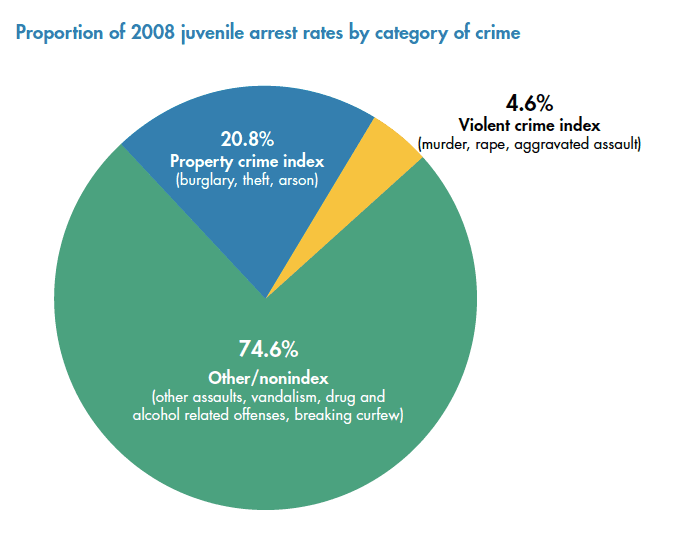

Just over two million youth under the age of 18 were arrested in 2008. Of these two million, about 95 percent had not been accused of violent crimes, such as murder, rape, or aggravated assault. In 2010, of the nearly 100,000 youth under the age of 18 who were serving time in a juvenile residential placement facility, 26 percent had been convicted of property crimes only, such as burglary, arson, or theft. For nonviolent youth involved in the juvenile justice system, incarceration in traditional residential placement facilities often does more harm than good. These large residential facilities are ineffective at providing the services and rehabilitation these youth need, and this lack of capacity contributes to high recidivism rates (re-arrest within one year of release). Reliance on these residential placement facilities is an inefficient use of taxpayer money, not only with regard to the funds needed to keep youth in these facilities, but also the future lower wages and lost productivity that often follows for these youth.

Reform efforts must place a greater focus on improving access to mental health services for all youth, better serving the needs of youth who are involved in the juvenile justice system, and creating effective alternatives to traditional residential placement facilities. Proper treatment and rehabilitative services can help many youth currently in the juvenile system become healthy and productive members of society.

Youth Offenders

From 1999 to 2008, the overall rate of youth under the age of 18 involved in the juvenile justice system declined, but individual rates and changes in these rates vary.

Type of Crime

Between 1999 and 2008, changes in juvenile arrest rates varied by type of crime.

Arrest rates decreased 24 percent for public drunkenness, 27 percent for driving under the influence, and eight percent for vandalism.

Arrest rates decreased nine percent for murder, 27 percent for rape, and 50 percent for motor vehicle theft.

Rates for robbery increased 25 percent.

Gender

In 2008, female offenders made up a greater proportion of juvenile arrests compared to their 1999 cohort (30 percent, up from 27 percent).

Between 1999 and 2008 the female arrest rate decreased significantly less than the male arrest rate in most categories of crimes, with some exceptions.

For property crimes, the male juvenile arrest rate decreased 28 percent, while the female juvenile arrest rate increased one percent.

For disorderly conduct, the male juvenile arrest rate decreased five percent, while the female juvenile arrest rate increased 18 percent.

For arrests related to driving under the influence of alcohol (DUI), the male juvenile arrest rate decreased 34 percent, while the female juvenile arrest rate increased seven percent.

Race/Ethnicity

Disproportionate rates appear when comparing 2008 arrest rates by race/ethnicity.

The majority of juveniles arrested were African-American, while they constitute only 16 percent of the U.S. juvenile population.

African-Americans accounted for 58 percent of all juveniles arrested for murder, 67 percent of arrests for robbery, and 45 percent of arrests for motor vehicle theft.

For violent crimes, African-American juveniles had an arrest rate five times that of White juveniles, six times that of Native Americans, and 13 times that of Asian-Americans.

Compared to their peers who committed similar offenses, African-American juveniles were more likely to be sentenced to placement facilities.

Although Whites and African-Americans made up similar percentages of youth in resi- dential facilities (35 percent and 32 percent, respectively), when compared to the general youth population of each race, the pro- portion of African-Americans in residential facilities was four times higher than the same proportion for Whites.

Spotlight: Treating Youth as Youth In most scenarios, once a juvenile has been accused of a crime, he or she appears in juvenile court and the case is heard by a judge who decides upon a sentence. From here, most juveniles receive some form of punishment, such as probation or community service. Oftentimes, the sentence might call for placement in a traditional juvenile residential placement facility. For those who are charged with serious crimes, including murder, assault, and robbery, many states have systems in place that allow the transfer from juvenile court to adult court. From here, youth face the possibility of incarceration in an adult prison, where juveniles will be even less likely to receive the necessary therapeutic and rehabilitative services than they would in juvenile residential facilities. Below are some of the methods states use to adjudicate juveniles as adults. Judicial waiver: Gives judges the discretion to determine whether a juvenile offender should be tried in adult criminal court. In cases when juveniles are charged with the most severe violent crimes, such as murder, judges may consider transfer to adult court the appropriate response. Forty-five states have some form of judicial waiver. Prosecutorial discretion: Allows prosecutors the discretion to determine whether a juvenile offender should be tried in adult criminal court, without any hearing or set standard. Fifteen states allow for prosecutorial discretion. Statutory waiver or automatic transfer: Allows for juveniles to be sent automatically to adult criminal court based solely on the category of crime they are charged with. Twenty-nine states have statutory waiver. Once adult/always adult: Requires juvenile offenders who were previously in adult criminal court to be transferred automatically for any future crime. This policy exists in 34 states. Transfers of youth from juvenile court to adult criminal court are not exclusively reserved for the most violent juvenile offenders. In adult prisons, these youth are far less likely to receive important rehabilitative services they need. In addition, youth confined to adult prisons are more likely to be abused or attacked by adult prisoners. Various studies from New York, Pennsylvania, and Florida have found that the recidivism rate for juveniles who served in adult prisons is significantly higher than those who remained in the juvenile system. In one study, the rate was reported to be nearly 30 percent higher than the usual juvenile recidivism rate.The recidivism rate drops even more when juveniles are placed in community-based centers as an alternative to traditional residential facilities. |

Youth in Juvenile Residential Placement Facilities

While youth who are charged with the most serious and violent offenses are more likely to be tried as adults and sentenced to adult prison, juveniles with more mid-range offenses, including burglary, theft, or repeat juvenile offenders, often spend time at a traditional juvenile residential placement facility. These large residential placement facilities can range in both setting and security, from rehabilitation camp-like programs to juvenile prisons.

Mental Health Needs

In a 2006 survey, juvenile offenders reported symptoms of mental health illness and trauma, regardless of age, race, or gender.

A majority of juvenile offenders in residential facilities had at least one mental illness.

Two-thirds reported symptoms associated with high aggression, depression, and anxiety.

At 27 percent, the prevalence of severe mental health illness among incarcerated youth is two to four times higher than the national rate of all youth.

Thirty percent of incarcerated youth reported a history of either physical or sexual abuse.

Many youth in residential facilities had histories of alcohol or substance abuse.

Seventy-four percent of youth had tried alcohol at least once, compared to 56 percent of their non-incarcerated peers.

Eighty-four percent of youth had tried marijuana, compared to 30 percent of their non-incarcerated peers.

Lack of Mental Health Services

While most juvenile residential facilities offer at least some therapy or counseling services, a nationally representative survey of over 7,000 incarcerated youth demonstrated that the majority of these facilities are ill-prepared to adequately address the needs of youth in their custody. Many of these facilities lack any early identification system to screen and identify those with mental health needs. A lack of early identification or screening can result in youth going without needed care.

Forty-five percent of youth are incarcerated in facilities that do not screen all new youth in the first 24 hours.

An additional 26 percent of youth are incarcerated in facilities that do not screen any new youth in the first 24 hours. Further, many of the limited services available are underutilized or not utilized at all.

Fifty-three percent of youth are incarcerated in facilities that do not provide mental health evaluations for all.

Among youth with a documented mental health issue that are incarcerated in residential placement facilities, 47 percent have not met with a counselor.

Research shows that treating substance abuse can lower recidivism rates, but many facilities lack an adequate substance abuse screening system.

Half of the youth surveyed are in facilities that do not use standardized assessment tools to identify substance abuse issues, and 19 percent are in facilities that do not screen any youth for substance abuse.

Instances of violence between youth and facility guards have been documented at many facilities.

A Department of Justice Task Force report found that staff at Tryon Boys residential center in New York used excessive force and inappropriate restraints on youth.

Similar instances of violence were found in juvenile facilities in Indiana, Ohio, and California.

Community-based Alternatives

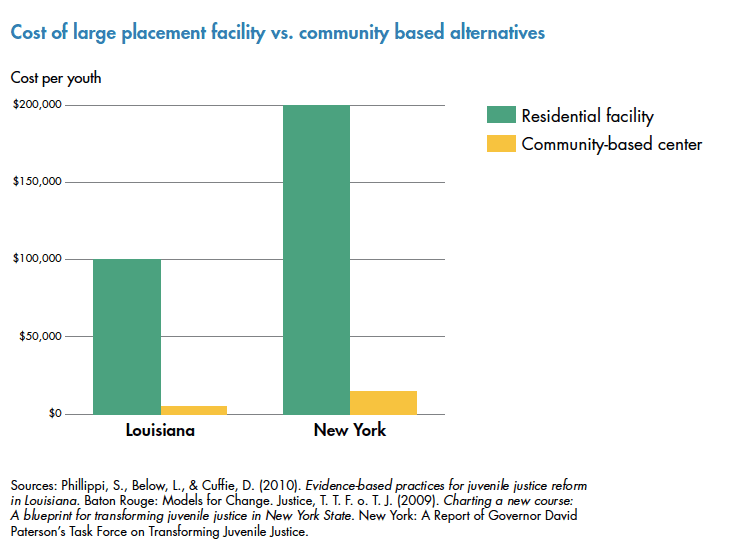

Recent research shows that community-based centers are often more effective than traditional residential placement facilities in achieving better outcomes for troubled youth, most notably in reducing the likelihood of repeat offenses. Common community-based alternatives include centers that youth offenders attend in the community each evening, home detention, short-term shelter care, and small community homes. Community-based programs and services can produce positive social outcomes, such as a decreased dependence on alcohol and illegal substances, especially in the first six months after release from a facility. These centers keep youth in their own communities while they receive punitive action, which is more likely to be developmentally and contextually appropriate and include necessary rehabilitative services. Unlike traditional residential placement facilities, community-based alternatives aim to keep youth in small groups so that they are able to receive necessary attention and services. Most community-based centers focus on evidence-based therapeutic services, especially multi-systemic therapy. It is less expensive for states to punish and provide needed treatment in the community than to place youth offenders in a large residential placement facility.

Even with limited resources due to budget cuts, some states are creating positive change.

In Missouri, most community-based facilities are designed for 10 to 30 youths with a strong focus on therapeutic intervention.

Only eight percent of youth offenders in Missouri return to the juvenile system once they are released, and only eight percent go on to adult prisons.

Research shows lower recidivism rates will save the state money in the long run, despite up-front costs involved in establishing these community-based facilities.

In Illinois, the number of juvenile offenders in traditional residential facilities has decreased as a result of fiscal incentives to communities to rehabilitate youth in community-based settings.

Youth who received community-based treatment are less likely to be involved in future criminal activities.

In its first three years, Illinois saved an estimated $18.7 million as a result of this program.

Expanding community-based alternatives could decrease the populations of traditional residential placement facilities, independent of changes in crime rates by type or severity.

Challenges

Dependence on transfers from juvenile court to adult criminal court. Currently, youth adjudicated as adults are often sent to adult prisons, where they are unlikely to receive appropriate rehabilitative services. Transfers often increase the likelihood of recidivism and poor life outcomes.

Many states allow transfer decisions to be made by prosecutors or by statute, not by judges, who may take the youth’s background and family situation into consideration.

Reliance on ineffective residential placement facilities.

Many youth offenders are not able to receive evidence-based, culturally competent rehabilitation.

The lack of needed services at these placement facilities contributes to longer-term problems and a greater chance of recidivism.

Lack of well-designed community-based alternatives or funding to support them.

Community-based alternatives need relatively limited resources to be effective.

States have cut community mental health budgets, which provide the majority of funding for community-based alternatives.

In 2009, at least 32 states cut these programs by an average of five percent, and many were planning additional cuts for the future.

Recommendations

Focus on Needs of Juvenile Offenders

Improve judicial transfer laws and limit the number of juvenile transfers.

Keeping youth offenders in juvenile court and out of adult court increases the chance of their receiving needed help and services.

Treat youth as youth, not as adults.

Encourage judges to take into account a youth’s development when determining the proper sentencing.

Provide youth in the system with developmentally appropriate and evidence-based therapeutic and rehabilitative services. Keeping them out of traditional residential placement facilities entirely, whenever appropriate, can prevent youth offenders from becoming adult offenders.

Improve Services at Residential Facilities

Ensure that more facilities offer and utilize necessary services, including early identification screening and evidence-based and culturally competent mental health services.

Ensuring access to quality medical and mental health care for youth in residential facilities can increase the likelihood of their successful rehabilitation and reentry into their communities.

Promote Community-based Alternatives

Create new community-based alternatives based on successful models, such as Missouri’s.

Smaller and more intimate community-based centers can enable more youth offenders to receive the help they need, decreasing present and future costs to the state and society.