PREFACE – BY RAYMOND WILLIAMS

Raymond Williams is a writer and advocate currently serving a death in prison sentence under the Persistent Offender Accountability Act at the Washington Corrections Center in Shelton, Washington.

The public expects that policies work for the betterment of society and that laws are grounded in good-faith efforts towards achieving this goal. We share a responsibility with each other to push ever-forward towards a fair and equitable society, and for our criminal legal system to achieve that amorphous concept we call justice. Because we are mere human beings, the laws we create often miss this mark. But there resides beauty in our capacity to recognize our wrongs, and redemption in our boldness to confront the errors of history.

In the social sciences, we are taught to evaluate a policy by its impact, rather than its intent. Focusing on impact reveals whether a policy is working as intended, or whether the policy is working at all. When we analyze the Persistent Offender Accountability Act (POAA), the data reveals that it does not produce measurable benefits to public safety, that it disproportionately affects people of color, inflicting immeasurable harm to the most marginalized communities in our state. We see a policy out of step with our evolving standards of decency. However, because one outcome of this policy includes disproportionate racial harm, we think it insufficient to simply offer an analysis on the impact of the POAA. When a policy egregiously misses the mark of decency and produces racially biased outcomes, it is important for society to understand how we arrived at a place so far from the ideals to which we aspire. Understanding our errors helps confront these mistakes and informs future generations, empowering them to learn from us and plot a more just course for our future.

This report explores the history and ideology of the architects and advocates that drove the POAA. We find the POAA is, at its heart, an instrument of racial vengeance. From the beginning of the campaign for this law, legal professionals and community advocates raised concern that this law would harm marginalized communities. This potential racial harm did not dissuade the POAA’s architects. In fact, racial animus and racist ideology are shown to prevail in statements made by the architects and advocates of the POAA, both during and after the creation of this law. This history reveals that racial harm was, at the very least, a byproduct welcomed by the architects of the POAA.

John Carlson, the primary architect of “Three Strikes, You’re Out,” wrote in 1993 that Black rap artists embody “a culture that sees [B]lack women as [b****s’] and [‘wh***s,’] and [B]lack men as obsessed with sex, contemptuous of authority, and worthy of respect only in relation to their capacity to kill or maim others.”2

William J. Bennett, former Secretary of Education under President Ronald Reagan, and early proponent of the POAA, is also known for his racist views. Bennett campaigned in Seattle for the POAA in 1993,3 and then in 2005, espoused his view that crime rates would go down if all Black babies were aborted.4

Today’s society owes no allegiance to, and can stand no relationship with, people espousing racist views, nor with the policies birthed by them—especially when those policies produce racially disparate outcomes.

At its base, the POAA is a product of a 1990s zeitgeist led by racist politicians and media who exploited public fear of crime as a mechanism to institute control and oppression over already marginalized communities. Rhetoric used during the promotion of the POAA featured highly racialized narratives promising to rid the streets of “thugs”—a trope regularly wielded by John Carlson.

People like Carlson held complete disregard for socioeconomic issues plaguing marginalized communities, willfully otherized whole segments of our population, and sought policies that weaponized the criminal legal system against Black people.

Three Strikes, You’re Out” is no different, no less damaging, and no less steeped in racial animus than the super-predator narrative—a theory also born in the 1990s—that has since been debunked and recanted. In fact, remnants of the super-predator influence are inextricable from the POAA, as both presume the behavior of young people warrants incapacitating them to the point of death. The POAA requires, at the moment, 22 people, including me, to die in prison for strikes they committed as youth under the age of 18.

Viewing the historical context surrounding the creation of this law and assessing public statements made by its proponents allows us to draw a thread between impact and intent. The conclusion is stark: the POAA is working as it was intended. The racially disparate impact of the law is likely a product of design, rather than an unintended consequence. What we have inherited in the POAA is a law informed by racist ideology having racially disparate impacts. This policy is beyond the countenance of decency.

“Three Strikes, You’re Out” is a legacy owned by the state of Washington. We were the first state in the nation to pass such a law, setting a precedent for the many states that followed. This mark stains the Evergreen State, blighting our emerald virtues. We spread this idea, like a fungus, to our brother and sister states across the nation. Because we led the nation in this policy, we have a responsibility to help lead the nation away from it.

We should take action. We should distance ourselves from people like John Carlson. For our redemption, and for the sake of healing the community, we must strike “Three Strikes, You’re Out” from the criminal legal system and purge ourselves of this regressive law.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Three Strikes law is grossly unfair. Locking people up for life under the Persistent Offender Accountability Act (POAA) is an overcorrection that is not making our communities safer. Instead of identifying and incarcerating the most dangerous, it selects those who have been failed by the other systems that foster healthy communities and provide the material conditions needed to thrive. And it does this with an undeniable and indefensible racial impact. This report, produced through comprehensive research, is intended to educate interested stakeholders and community members about the impact, history, and operation of Washington’s POAA.

“Three Strikes, You’re Out” has at least five strikes against it: (1) it is overly retributive, punishing much more harshly than is justified, which makes it an immoral punishment; (2) it fails as a deterrent, making it ineffective as a policy choice; (3) it excessively over-incapacitates, imprisoning people far beyond when they would continue committing serious offenses; (4) it fails to allow for rehabilitation and redemption; and (5) it is applied in a racially disparate manner, making this punishment arbitrary and hence cruel. Ample research demonstrating the first three points already exists. This report focuses on the latter two—the denial of redemption and the striking racial injustice. It also provides historical context of the POAA and explains in detail why repeal of the POAA is a justifiable policy choice that would leave the rest of Washington’s Sentencing Reform Act (SRA) intact.

Interspersed through this report are the stories of five men who have been directly harmed by the POAA. These stories appear throughout the report to center the human and societal cost of this law. Joshua, Raymond, and Walter are serving life without parole (LWOP) sentences under this law, even though each has taken accountability, grown as a human being, and chosen to make a positive impact in the world. Nothing is gained by keeping them locked up until they die, but so much is lost. “The State does not execute the offender sentenced to life without parole, but the sentence alters the offender’s life by a forfeiture that is irrevocable. It deprives the [person] of the most basic liberties without giving hope of restoration, except perhaps by executive clemency—the remote possibility of which does not mitigate the harshness of the sentence.”5 Orlando and Marcus obtained release through the clemency process and are now leading peaceful and productive lives, making meaningful contributions in the greater community. Their work helps people succeed when they come back to the community and also focuses on avoiding incarceration all together. Despite facing death in prison sentences, these men have not allowed the POAA to quash their spirit or their human potential.

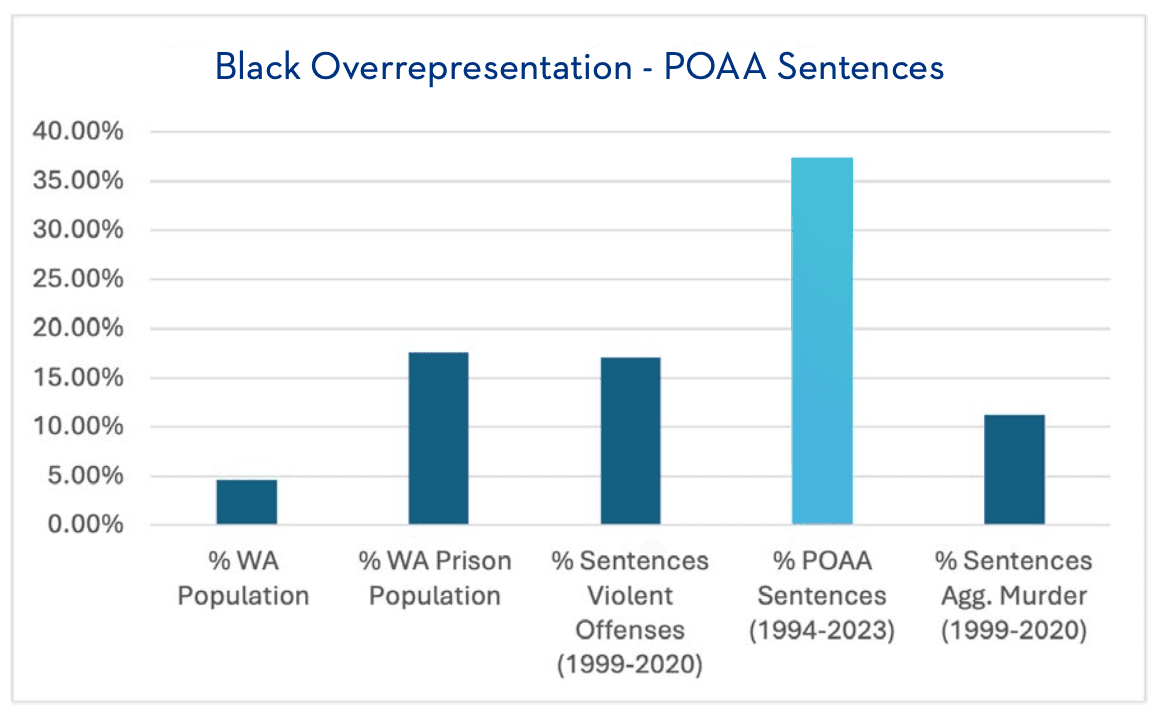

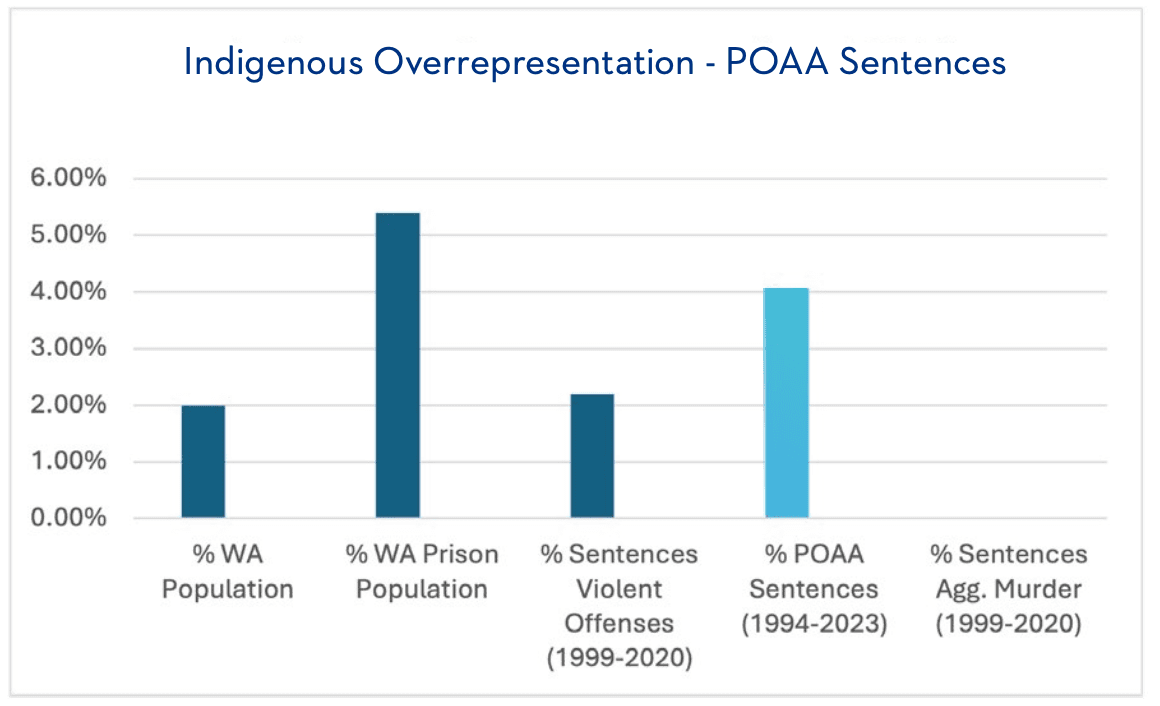

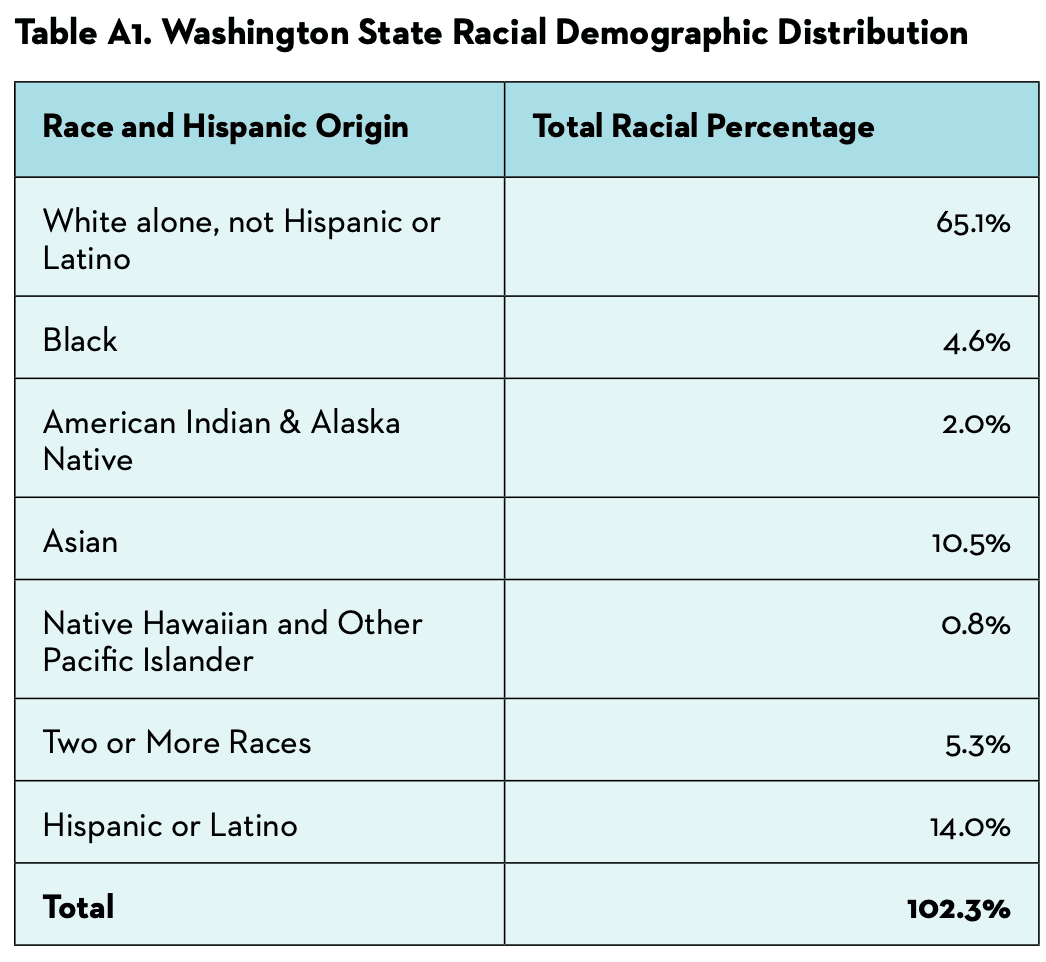

The report begins by examining the racial impact of the POAA through data. The racially disparate application of the Three Strikes Law has been documented since shortly after the law’s passage and has held constant for more than two decades. This report presents the most recent data related to overrepresentation and disproportionality of people of color caused by the POAA. Demographic data on all POAA sentences was gathered for this report and shows that Black people are represented in the three-strikes population at a rate more than 8 times greater than their population in the state. Indigenous people are also overrepresented—making up 2% of the state’s population and over 4% of those sentenced to life without parole under the Three Strikes Law. While racial disproportionality is a problem throughout the criminal legal system,6 it is most severe in the three-strikes context, where the punishment is the harshest.

“The State does not execute the offender sentenced to life without parole, but the sentence alters the offender’s life by a forfeiture that is irrevocable. It deprives the [person] of the most basic liberties without giving hope of restoration, except perhaps by executive clemency—the remote possibility of which does not mitigate the harshness of the sentence.” — Justice Anthony Kennedy

Analysis of the data gathered for this report also demonstrates that the racial disparities are not fixed by making adjustments to the law—in 2021, those serving POAA sentences on the basis of a Robbery 2 conviction became eligible for resentencing, and were no longer subject to the POAA. While this was a necessary change to address the unfairness of including less severe conduct, it did not have a measurable impact on the overrepresentation of people of color in the POAA population. The data demonstrate that no matter the subcategory of POAA sentences examined, significant racial overrepresentation persists. If Assault 2 were removed from the strikes list, total three-strikes sentences would be reduced from 270 to 128, but even more severe racial disproportionality would remain.

The POAA—the first law of its kind in the nation—was enacted based on fear at a specific moment in our nation’s cultural experience, in reaction to racist narratives around crime. The three-strikes concept was devised by conservative political analyst and talk radio host, John Carlson, in the late 1980s. After working for several years to garner public and legislative support, the law finally passed as an initiative to the people, I-593, with the financial and organizing support of the National Rifle Association (NRA). Voters were told that the worst of the worst criminals would be locked up for life and that doing so would make communities safer. More than 30 years later, we know that the law has not solved the problem it was intended to address. Research has found no evidence that three strikes laws reduce crime by deterring criminal activity or incapacitating people who have committed multiple crimes. Studies also show that these laws have no measurable impact on crime rates overall in the jurisdictions where they are enacted, and Washington is no exception.7

Under the POAA, anyone convicted of three “most serious offenses” is deemed a “persistent offender” and sentenced to life without parole. The crimes included in the law represent a broad range. While most are more serious violent crimes (class A felonies), some less serious crimes (class B and C felonies) and juvenile strikes (strike offenses committed by those under age 18) also count.

The mandatory imposition of an LWOP sentence for all combinations of underlying offenses—with no room to consider other circumstances either at sentencing or after a period of incarceration—makes this law exceptionally harsh. In 2018, the Washington Supreme Court invalidated the state’s death penalty statute because it was applied in a racially arbitrary manner. After this decision, life without parole is the harshest available punishment in Washington and is imposed only for aggravated murder or after three strikes. Under the POAA, every person who meets the definition of a persistent offender MUST receive the harshest punishment in the state—whether that person committed three serious violent offenses or got into three fist fights that injured the victim.

In the early 1980s, Washington adopted the SRA, a determinate sentencing scheme that was intended to reduce disparities and increase predictability in sentencing. Proponents of I-593 argued that the POAA was necessary because people who committed repeat crimes were not adequately punished under existing law. The explanation of the SRA, which requires longer sentences for those who have committed multiple prior offenses and imposes increasingly long sentences as the crimes rise in seriousness, shows why the existing sentencing scheme does not let people off easy. Finally, the SRA transferred discretion from the judge to the prosecutor. Through their charging decisions and negotiation tactics, prosecutors hold tremendous control over whether someone is subject to a three-strikes sentence.

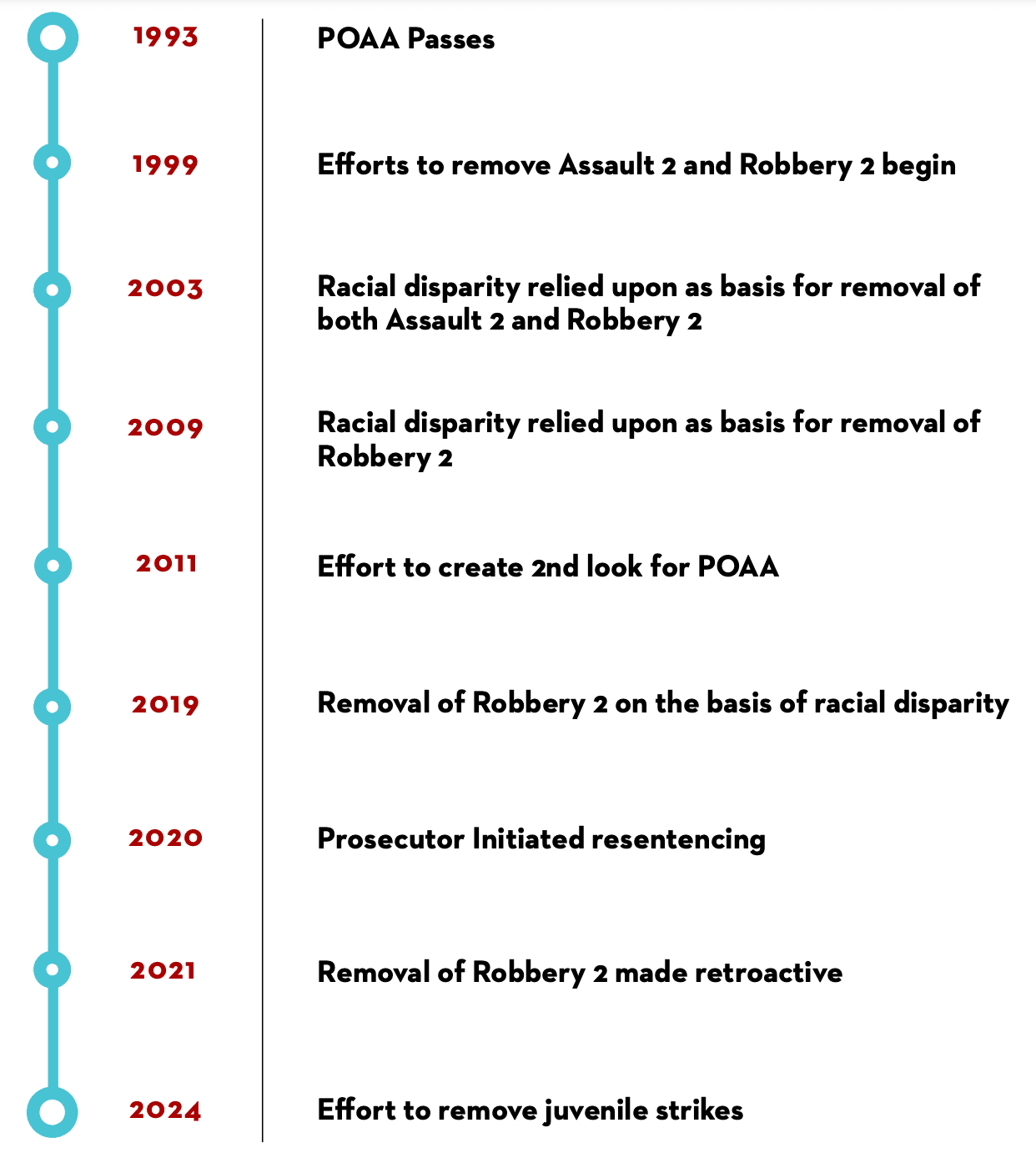

Many legislative attempts to reduce the reach of the law have been introduced, starting soon after the law went into effect. Most have failed. These proposed bills have primarily recommended removing specific crimes, such as Robbery 2, Assault 2, and juvenile strikes, from the list of strike offenses, or have attempted to establish early release for those who have a less serious strike offense. However, only one legislative effort has had a meaningful impact in addressing the harms of the POAA. In 2019, the Legislature removed Robbery 2 from the strikes list, and in 2021 the change was made retroactive. This resulted in nearly 200 fewer POAA sentences. While a handful of Washington prosecutors have also been vocal about the unfairness of the POAA and have made a concerted effort to address the over-inclusiveness of the law, most have not. Many prosecutors also take the position that prosecutor-initiated resentencing is not available for mandatory LWOP sentences under the POAA. Second-look systems present a more promising approach for reducing the harm resulting from permanency of LWOP sentences. Creating an opportunity for release avoids unnecessary incarceration of the many people who can demonstrate that they can safely release to the community, just like Marcus and Orlando have.

Any reform of the POAA short of complete repeal will be insufficient to address the harms it causes—most strikingly, the extreme racial disproportionality that has resulted since the law’s inception. Until such a change is politically viable, advocates and lawmakers should consider the short set of recommendations included at the end of this report when devising reforms that might, at a minimum, lessen the impact of the law and transform the lives of those who could return to the community—and who could transform our communities as a result.

RACIALLY ARBITRARY AND DISPROPORTIONATE PUNISHMENT UNDER THE POAA

Lawmakers and state actors have known since soon after the POAA became law that it was resulting in significant racial disparities8 that are not explained by differences in crime commission rates.9

In 2000, the Washington Sentencing Commission reported that Black people were sentenced to LWOP under the Three Strikes Law at a rate 18 times higher than white people, and Indigenous people were sentenced under the POAA at a rate over three times higher than white people.10 In 2009, the Sentencing Guidelines Commission found only 52.2% of defendants sentenced under the three strikes law were white, while 40.4% were Black.11 And the next year, Columbia Legal Services issued a report similarly concluding that, as of 2009, only 47% of three-strikes defendants were white, while 39.6% were Black.12 This report emphasized the extraordinary nature of the disparity given that only 3.9% of the state’s population at the time was Black.13

The awareness of these disparities has not resulted in changes significant enough to demonstrate that the law can be applied in a way that is not racially arbitrary. The data demonstrates that no matter which portion of the three-strikes population is analyzed, severe racial disproportionality persists with respect to Black and Indigenous people.

Compounding the racially disparate impact is the POAA’s indiscriminate punishment of different categories of criminal conduct: it treats the most serious class A felonies identically to other less serious crimes, such as those committed under age 18 and some class B and C felonies.14 While these crimes cause harm, these less serious strike offenses do not warrant imposition of the harshest punishment available in Washington.

Racial Disproportionality of All Three Strikes Sentences

Three strikes data through fiscal year 2023 presented below demonstrates that the same severe racial disproportionality15 that has plagued the POAA since its inception has persisted, despite growing awareness of implicit bias and institutional and systemic racism. By any measure, the POAA is imposed disproportionately on Black and Indigenous people.16

In 2019 and 2021, the Legislature first removed Robbery 2 from the list of strike offenses, and then made the amendment retroactive, partly because of concerns about racial disproportionality.17 But even after removing Robbery 2 from the list of most serious offenses, extreme racial disproportionality persists in three-strikes sentencing.

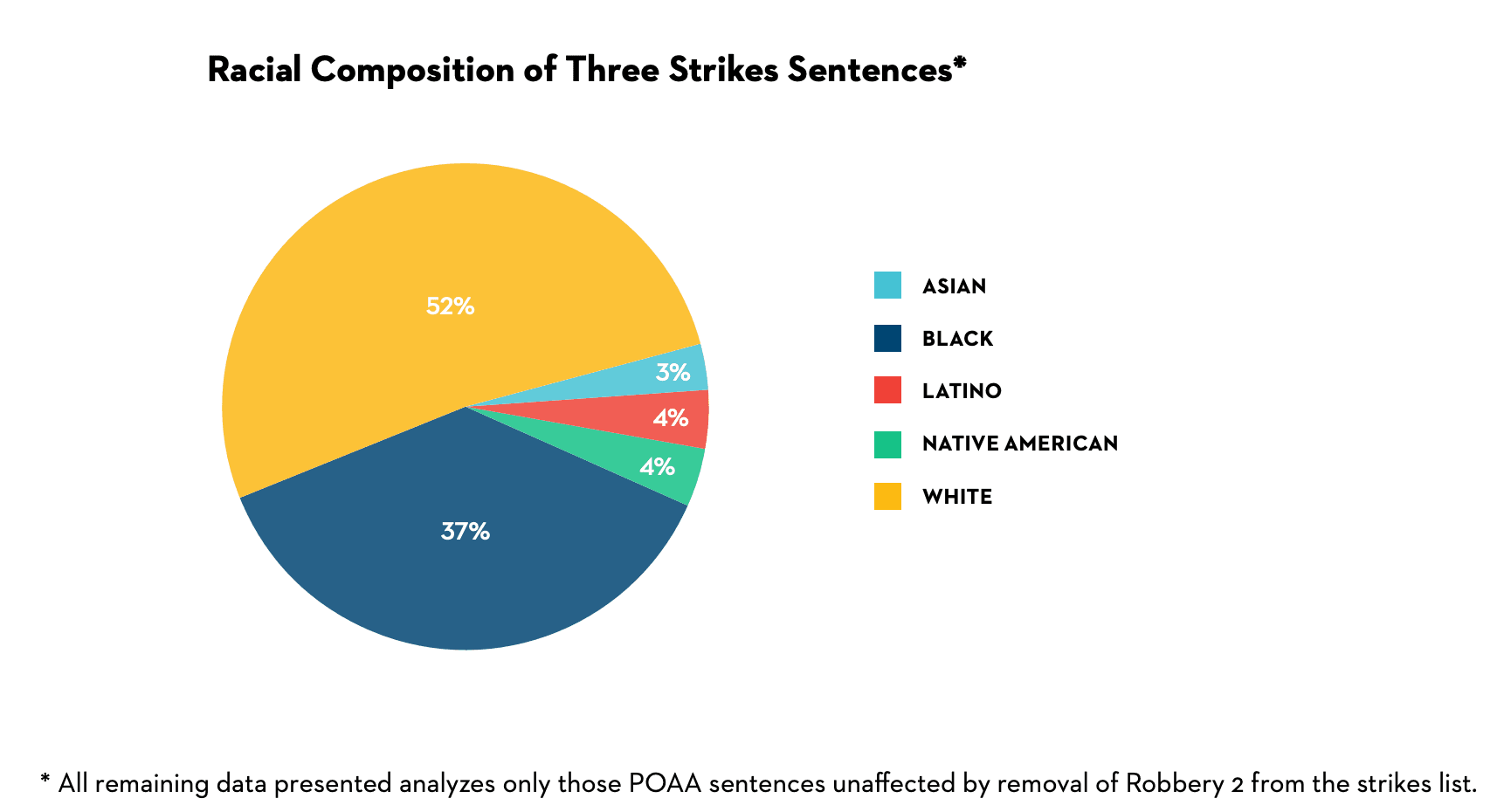

Before Robbery 2 was removed from the strikes list, Black people received 41% of the total of three-strikes sentences imposed. While the removal of Robbery 2 shrunk the reach of the POAA considerably, reducing POAA sentences from 469 to 270, it left racial disproportionality virtually unchanged. Removing those cases eligible for resentencing because of the removal of Robbery 2,18 Black people have now received just over 37% of the total of three-strikes sentences imposed.

“The data demonstrates that no matter which portion of the three-strikes population is analyzed, severe racial disproportionality persists with respect to Black and Indigenous people.”

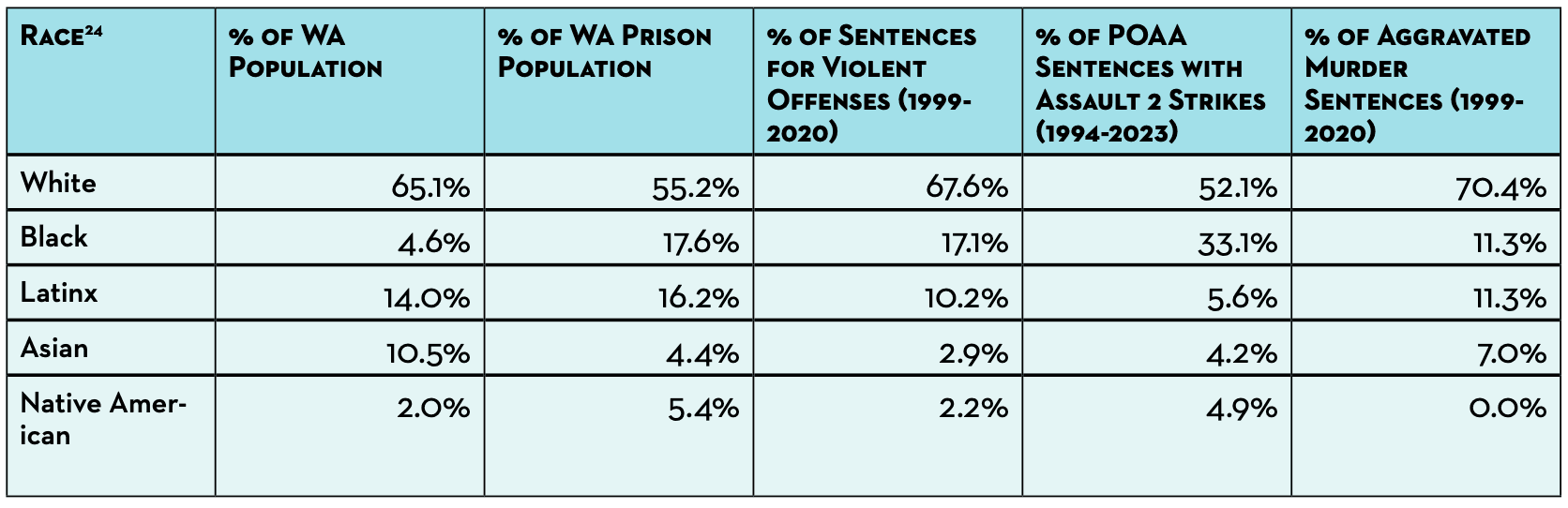

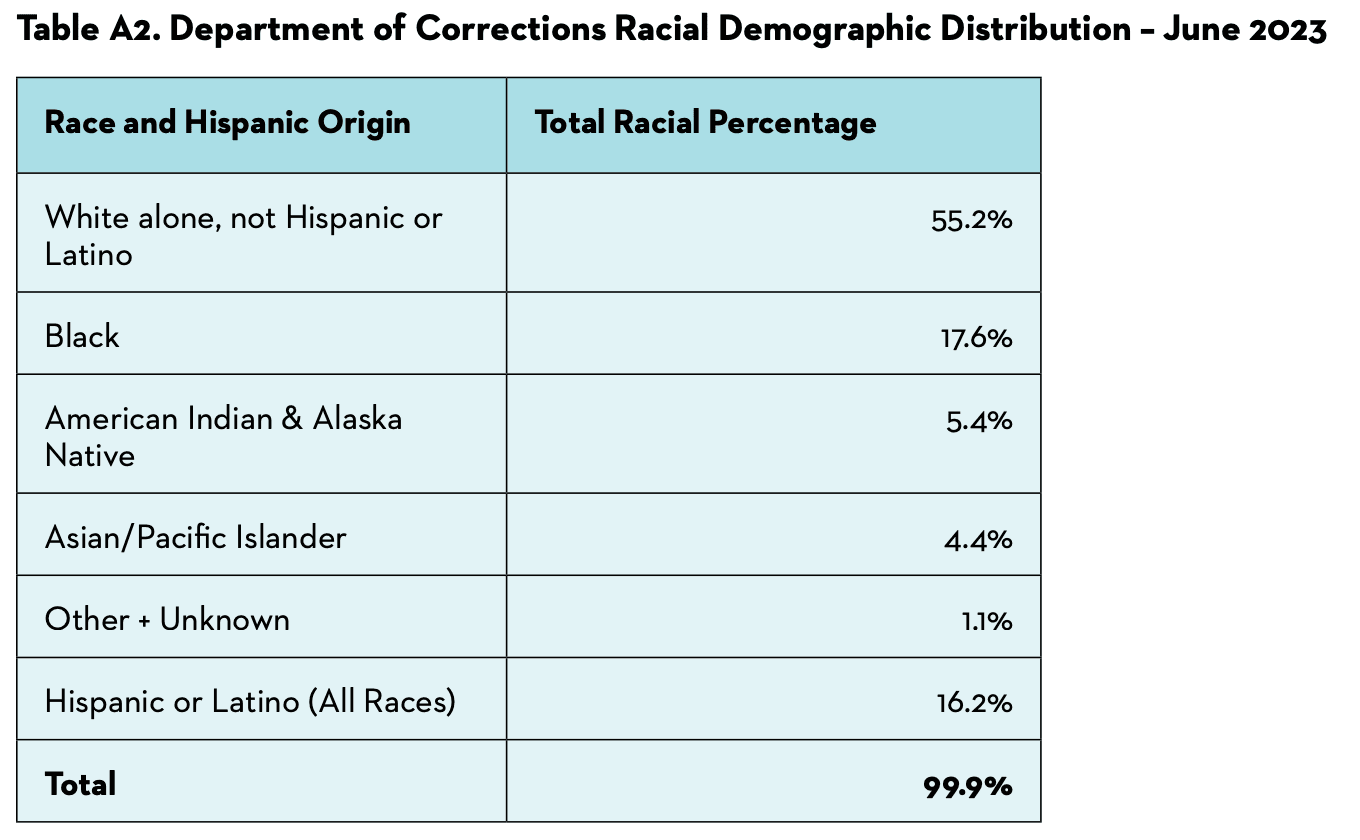

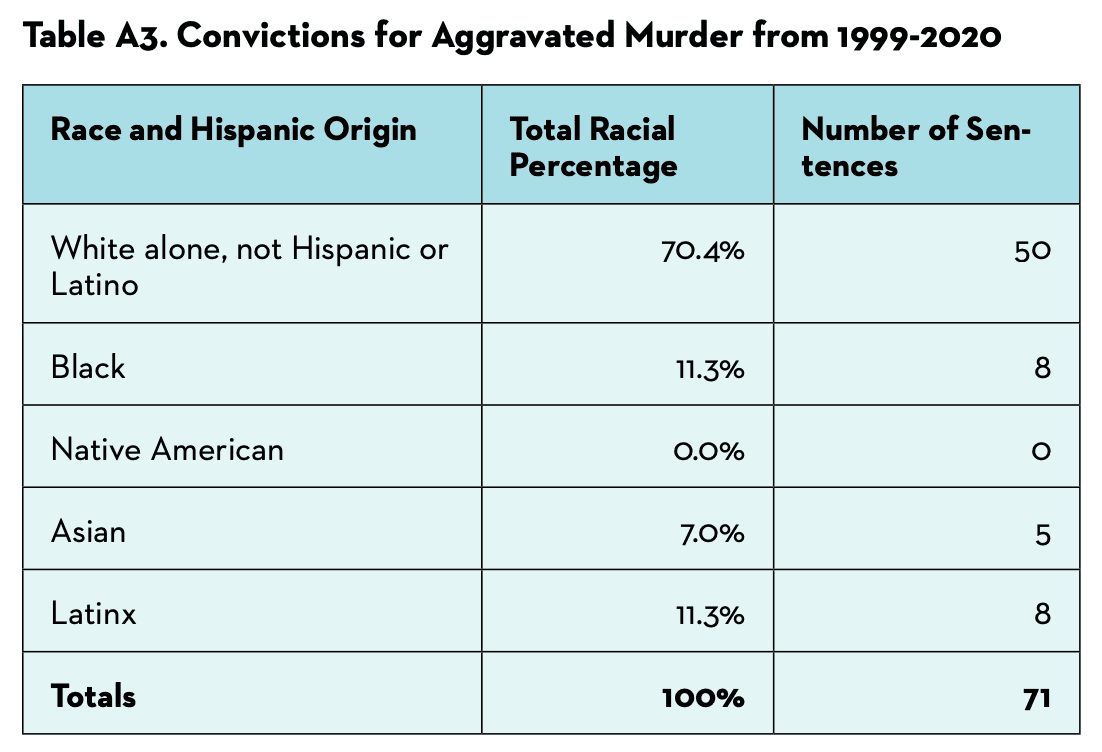

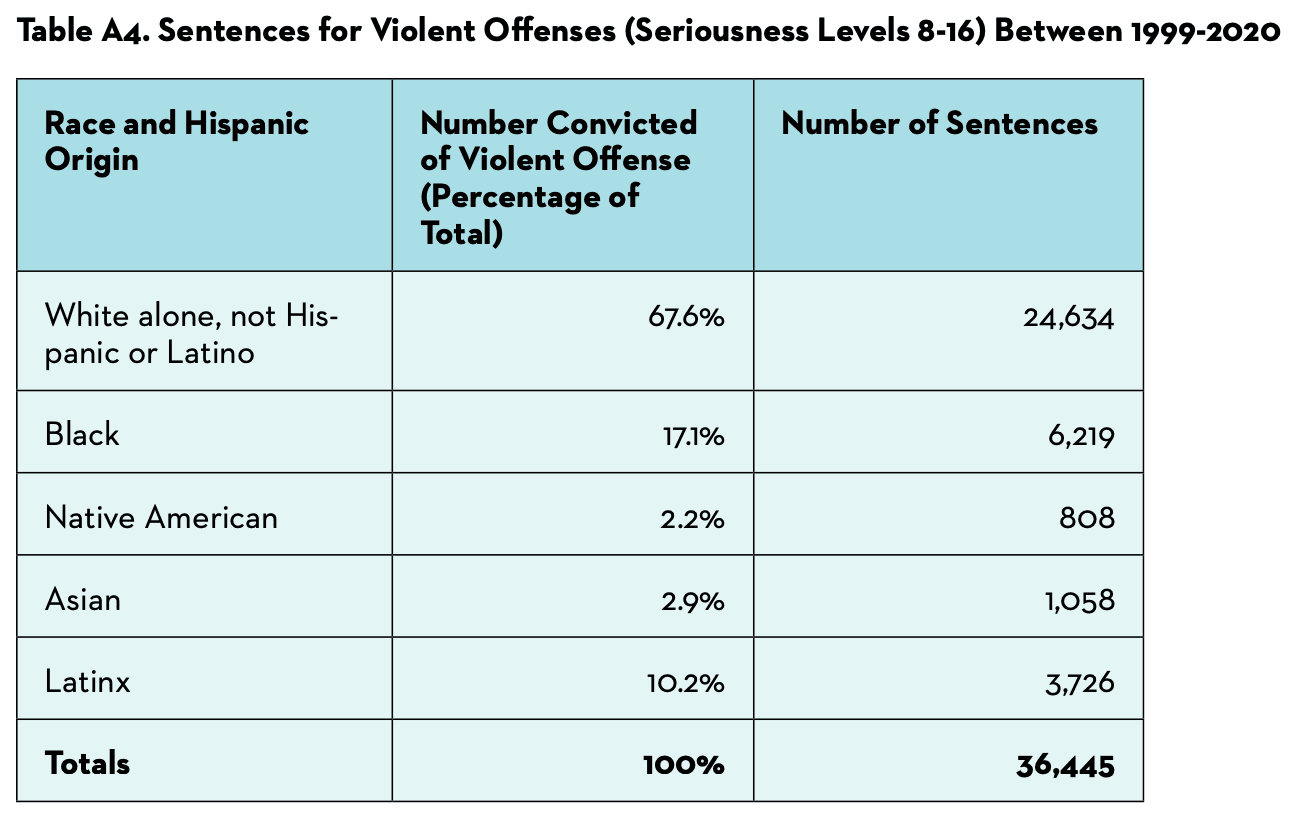

This is a striking statistic in a state where only 4.6% of Washington’s population is Black.19 This is also a striking statistic where 17.6% of Washington’s prison population is Black—a population where disproportionality is already embedded. And finally, this persistent and severe overrepresentation of Black people receiving threestrikes sentences is not explainable either by reference to sentences for violent offenses or by reference to the worst of the worst crimes—Black people comprise only 17% of those sentenced for violent offenses between 1999-2020, and only 11.4% of those sentenced to LWOP for aggravated murder between 1999-2020.

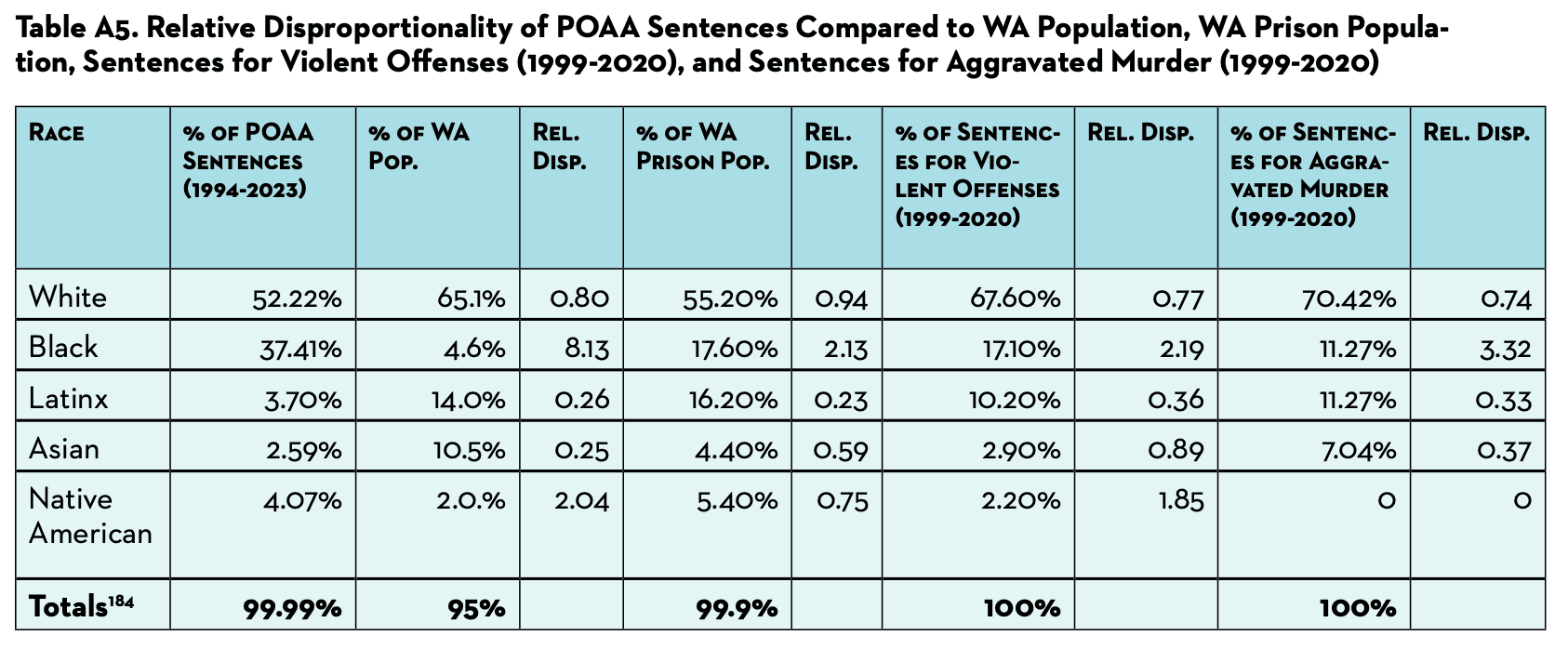

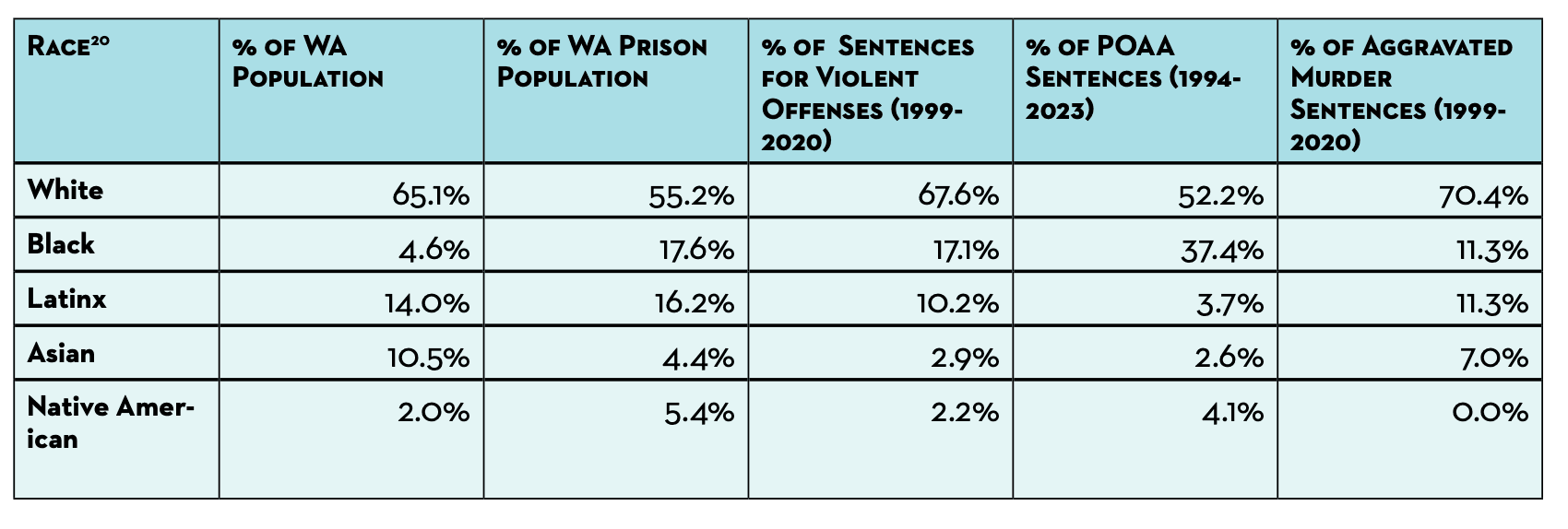

Table 1. Demographics of POAA Sentences Compared to WA State Population, WA Prison Population, Sentences for Violent Offenses (1999-2020), and Sentences for Aggravated Murder (1999-2020)

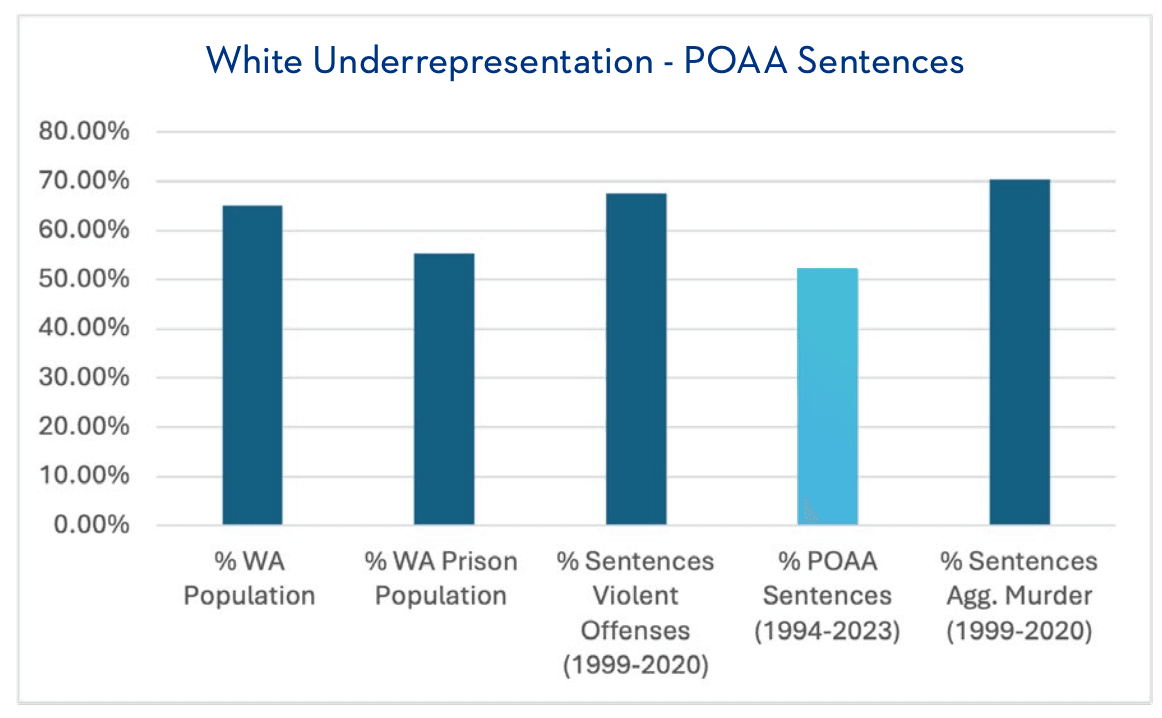

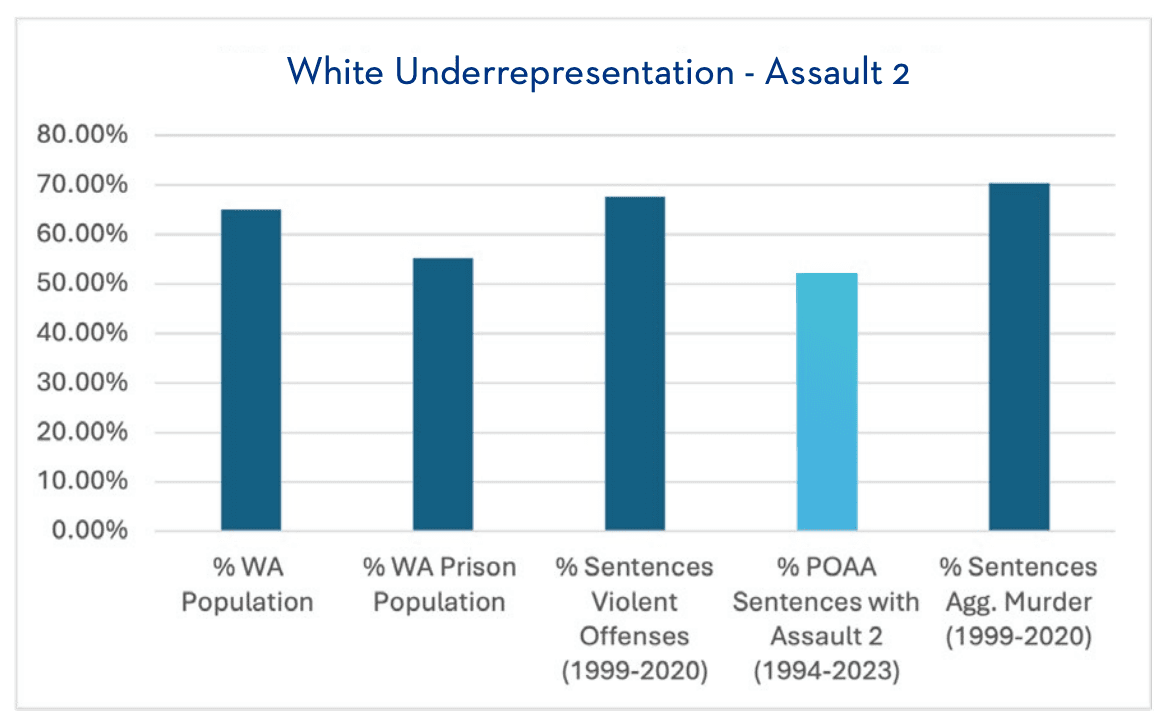

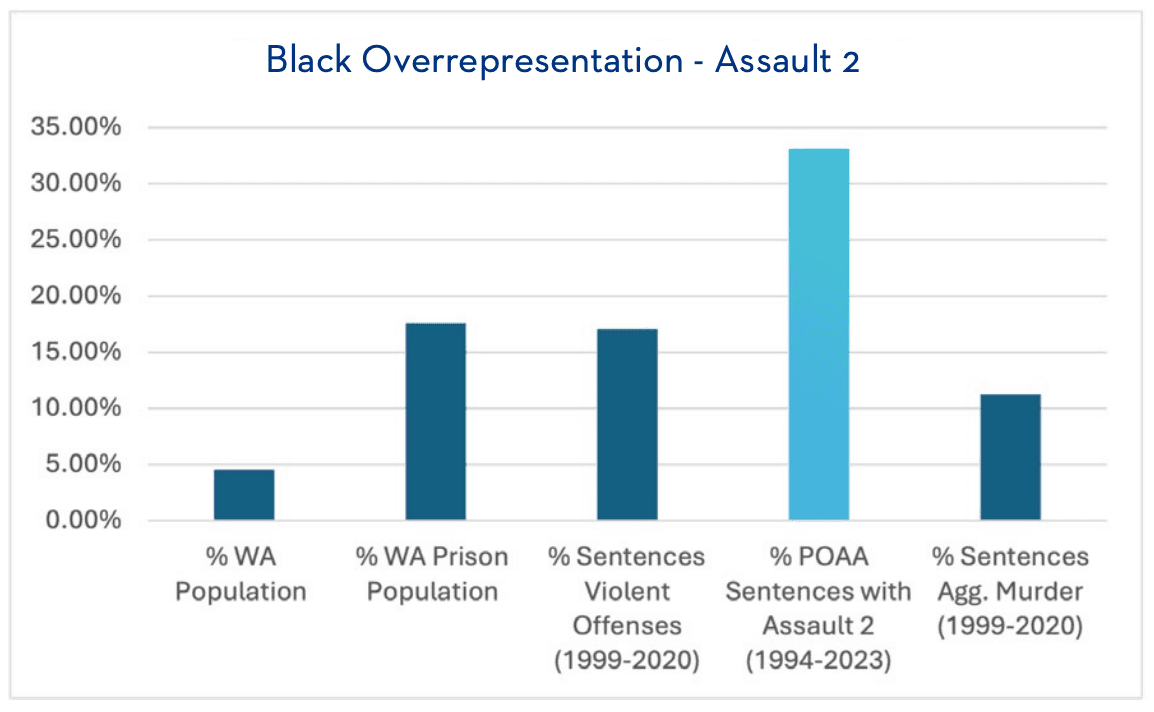

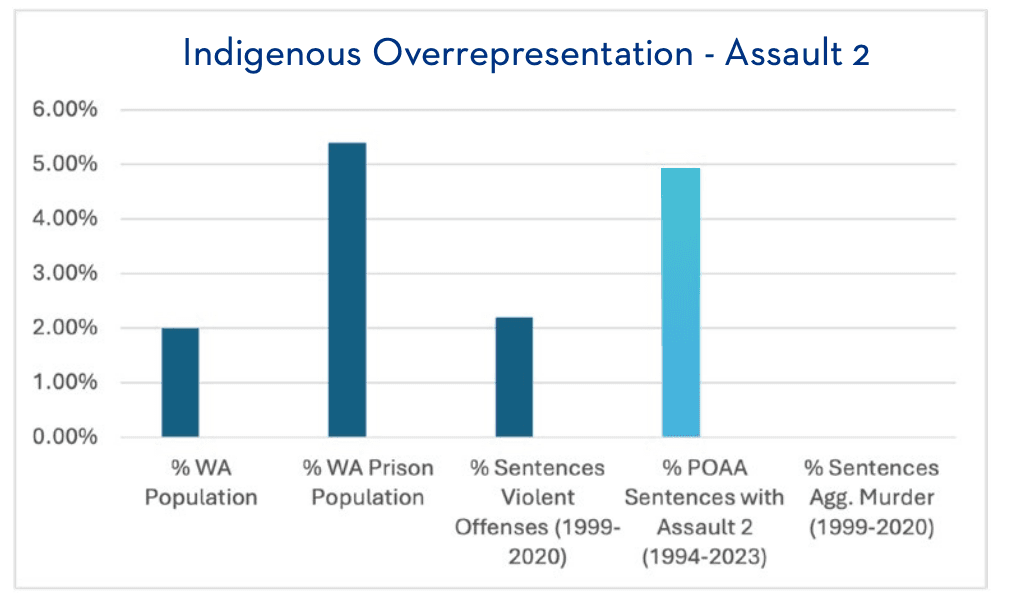

Figures 1-3. Demographics of POAA Sentences by Race, Compared to WA State Population, WA Prison Population, Sentences for Violent Offenses (1999-2020), and Sentences for Aggravated Murder (1999-2020)

Comparing the racial breakdown of the three-strikes population against the racial breakdown of other populations, such as statewide population, helps understand the level of disproportionality that exists by racial group. These measures demonstrate the severity and significance of the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people in the three-strikes population.21 Black people with three-strikes sentences are overrepresented relative to their share of the population by a factor of just over 8. Additionally, Indigenous people are overrepresented by a factor of 2, constituting 4% the individuals sentenced to life without parole since the law’s inception but only, but only 2% of the state’s population. These numbers are contrasted by the white population’s underrepresentation within the three-strikes population, constituting 52% of three-strikes sentences but 65% of the state population.

Finally, overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people in the three-strikes population is not explainable by reference to other more conservative alternative baselines—i.e., where disproportionality is already likely embedded. When compared to Washington’s prison population as of June 2023, Black people serving three-strikes sentences are still overrepresented by a factor of just over 2. When compared to sentences imposed for violent offenses between 1999-2020, Black people serving LWOP are overrepresented by a factor of over 2.2, and Indigenous people by a factor of 1.85. And when compared to sentences imposed for aggravated murder between 1999-2020, Black people serving LWOP are overrepresented by a factor of 3.3. These figures highlight the persistent overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people that is specific to three-strikes cases and not explainable by reference to prison population, to commission of violent offenses, or to aggravated murder.

Racial Disproportionality of Second-Degree Assault Strikes

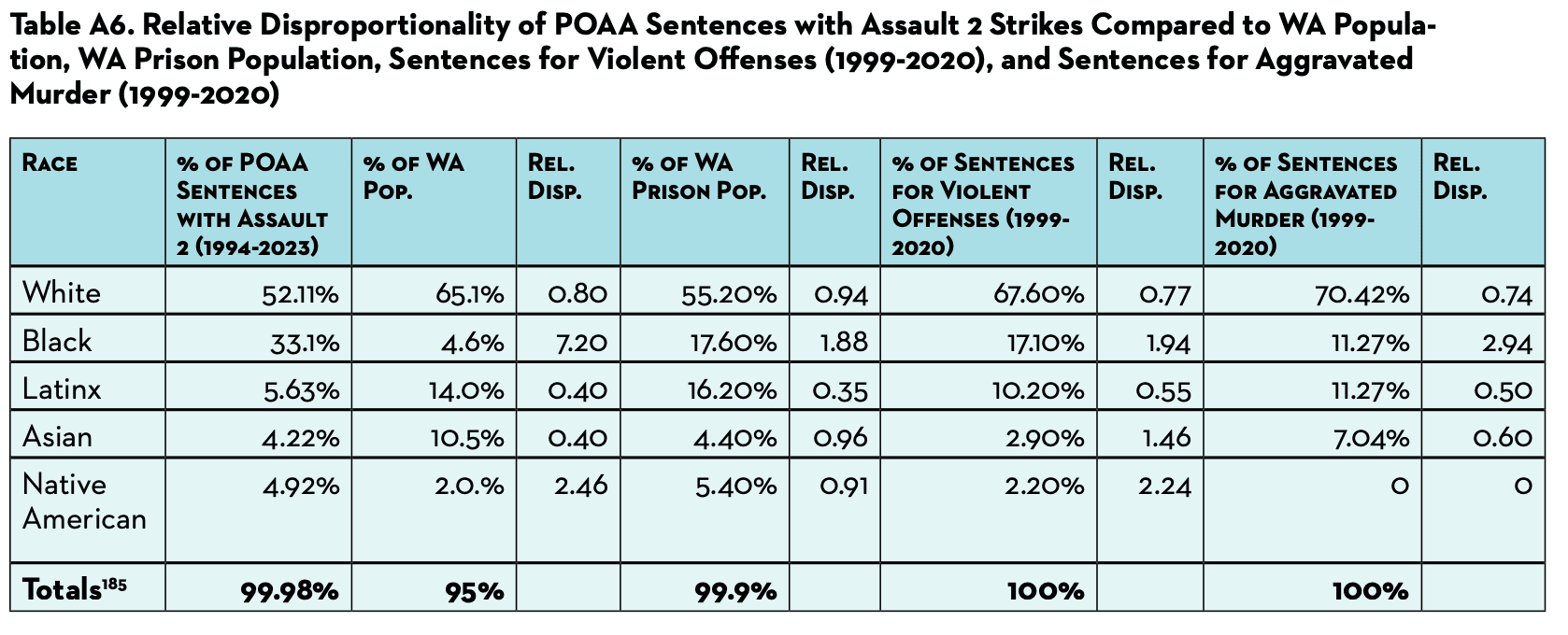

Assault 2 is a class B felony that encompasses a wide range of less-serious criminal conduct, and is the basis of 142 of the 270 three-strikes sentences after removing those eligible for resentencing because of the presence of a Robbery 2 strike.22 Significant racial disparity persists in those sentenced to die in prison due to one or more strikes for Assault 2. Of these 142 people, only 74 are white. In other words, while white people make up 65.1% of Washington’s population, they constitute only 52% of those sentenced to die in prison for an Assault 2 strike. In contrast, Black individuals account for 33% and Indigenous people account for 5% of those with an Assault 2 strike.

When compared to their representation in the state population, Black and Indigenous people with Assault 2 strikes are relatively overrepresented by factors of just over 7 and 2.5, respectively.23 When compared to Washington’s prison population as of June 2023, Black people serving LWOP based on one or more Assault 2 strikes are still overrepresented by a factor of 1.9. When compared to sentences imposed for aggravated murder between 1999-2020, Black people serving LWOP based on one or more Assault 2 strikes are overrepresented by a factor of nearly 3. And when compared to sentences imposed for violent offenses between 1999-2020, Black people are overrepresented by a factor of nearly 2. As with all three-strikes sentences, these figures highlight the persistent overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people that is specific to threestrikes cases with Assault 2 strikes, and which is not explainable by reference to prison population, to commission of violent offenses, or to aggravated murder.

Table 2. Demographics of POAA Sentences with Assault 2 Strikes Compared to WA State Population, WA Prison Population, Sentences for Violent Offenses (1999-2020), and Sentences for Aggravated Murder (1999-2020)

Figures 4-6. Demographics of POAA Sentences with Assault 2 Strikes by Race, Compared to WA State Population, WA Prison Population, Sentences for Violent Offenses (1999-2020), and Sentences for Aggravated Murder (1999-2020)

“...a person convicted of three Assault 2 strikes would receive the same sentence as a person convicted of multiple counts of aggravated murder, the only level 16 crime in Washington.”

For the category of those convicted of Assault 2, the sentence is grossly disproportionate and does not serve legitimate penological goals. Assault 2 has a seriousness level of 4 on a scale of 16, yet a person convicted Assault 2 as a strike would receive the same sentence as those convicted of strikes with seriousness levels near the top of the scale.25 Indeed, a person convicted of three Assault 2 strikes would receive the same sentence as a person convicted of multiple counts of aggravated murder, the only level 16 crime in Washington. Of the 74 people sentenced to die in prison based on at least one Assault 2 strike, 9 have struck out on three convictions of Assault 2. Four of those nine are Black, 4 are white, and 1 is Latinx.26

Other Less Culpable Strikes

The POAA also punishes other less culpable criminal conduct with a death in prison sentence. Crimes of attempt, solicitation, and conspiracy are anticipatory—by definition, the harm to the victim and the community is less serious, yet the POAA punishes these crimes the same as if they were completed. Because of the POAA’s structure, attempted class B and C felonies enumerated in the definition of most serious offense—which would be punishable as class C felonies or misdemeanors as stand-alone crimes under the SRA27—are included as strike offenses.28 Criminal solicitation or criminal conspiracy to commit a class A felony are also given the same treatment as a completed class A felony.29

There are currently 44 individuals serving a life in prison sentence without the possibility of parole based on one or more anticipatory crimes. Here too, the Black and Indigenous populations are severely overrepresented. Despite only making up 4.6 % and 2% of the state population, respectively, Black people make up 32% and Native Americans make up just over 11% of those serving a three-strikes sentence for an anticipatory strike.

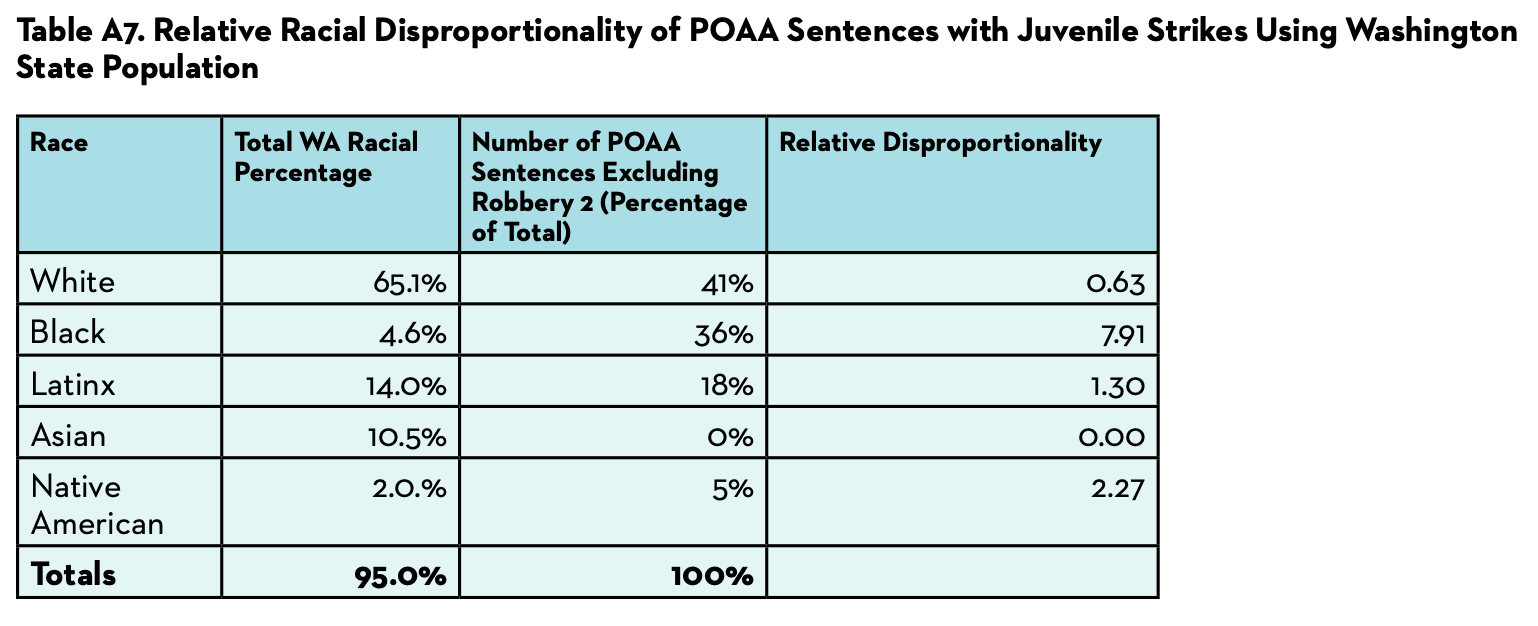

Juvenile strikes

Since the POAA’s inception, 32 individuals have been sentenced to die in prison under the Three Strikes Law because of juvenile strikes. Yet we now understand that “children are less criminally culpable than adults.”30 A child’s culpability is diminished by the neurobiological differences of the developing brain, but the POAA makes no distinction between strikes committed by children and those committed by fully culpable adults. On balance, for people with childhood strikes, legitimate penological goals are served much better by SRA sentences than by permitting a strike offense committed as a child to support a death in prison sentence.

Similar racial disproportionality exists within the population sentenced to die in prison based on juvenile strikes as in the entire three-strikes population. After excluding those with Robbery 2 strikes and excluding those no longer in DOC custody,31 22 people remain sentenced to die in prison as a result of juvenile strikes.32 Of these 22 people, 8 (36%) are Black and 9 (41%) are white. Black people with juvenile strikes are overrepresented relative to their share of the population by a factor of nearly 8, and Indigenous people by a factor of 2.3, while white people with juvenile strikes are underrepresented relative to their share of the population by a factor of just over .6.33

The racially disproportionate application of the Three Strikes Law persists—regardless of how it is measured, which sub-category of sentences is examined, and which sub-population is used for comparison. This problem has been documented from very early in the POAA’s existence, and an examination of the law’s origins permits an inference that this racial impact was intentional.

Narratives

Walter Cooper: What’s In Your Garden?

One brief conversation with Walter Cooper is all it takes to recognize that he is not the kind of “dangerous” individual from which society needs protection in the form of a life without parole sentence. Today, sitting in Walla Walla at the Washington State Penitentiary at age 62, Walter lives by his own personal motto: “what you plant today you eat tomorrow, so what’s in your garden?” During the 28 years Walter has been incarcerated, this motto has helped him live with an eye toward making his life count.

When Walter reflects on his earlier life, he recognizes that he was in survival mode. He was filled with anger but had no tools to examine it. Walter was born in Bremerton, WA, the third of six children. Walter’s mom, a single parent, worked three part time jobs to support Walter, his brother, and four sisters. Growing up, Walter loved to play soccer. A fast runner who played both forward and defense, he dreamed of being an “American Pelé.” As soon as he was able, Walter tried to make money to help his mom and pay for sports. He swept sidewalks, helped neighbors, and sold candy. But, when Walter saw how much money his older sisters were making selling marijuana, he began to sell too.

Walter sold marijuana from age 12 to 27. During this time, he bounced from couch to couch and sometimes lived on the streets. Eventually, his self-described “hustling” expanded to include a partner. Their efforts to survive led to his being convicted twice of Promoting Prostitution, a class B non-violent felony, in 1986 and 1988, when he was 24 and 26 years old. Both strikes occurred before the POAA was adopted in 1993. In fact, Walter did not learn about “strikes” until nine years later.

Following his release from prison for his second conviction in 1991, Walter turned his life around. At first he lived with his grandmother, and eventually found a place that would rent to someone with a criminal record. He worked in construction and did janitorial work. Then, in 1994, he met a woman at a barbeque. Things continued to improve as he stopped selling marijuana and had a daughter.

In 1996, it all came crashing down. Believing he was being threatened with a weapon, and wanting to protect his family, Walter got into a fight. He was sitting in jail charged with Assault 2, another class B felony, when his public defender told him the prosecutor was seeking life without parole under the POAA. Walter’s first shocked thought was, “what? For a fist fight?” Walter was not aware he had any prior strikes. He learned that no plea deal would be offered. His only hope to avoid dying in prison was to go to trial.

While Walter was awaiting trial, he had an awakening. During a phone call to his mom, Walter overheard his 4-year-old nephew say, “Grandma, it’s the jail uncle.” He decided then that he could not blame anyone else for his decisions and did not want to be known as the “jail uncle.” Walter vowed to focus on positive things and to make his life count, just as his grandfather urged him to do. Despite their poor health that made visits a challenge, Walter’s grandparents came to see him while he was in jail. Walter says their visit meant a lot to him, because when “someone on their last breath tells you you’re better than this – let your name stand for something positive, not something negative,” you do it. Walter credits his grandfather for his Christian faith.

Today, Walter proudly identifies as an “African American man of God.” He enjoys working as a personal care aid. Calling himself a “personal handyman,” Walter helps fellow prisoners with medical appointments. Walter also negotiated his way into a class not typically available to people serving life without parole sentences. The instructor of the “Communication Breakdown” class liked Walter so much he asked him to be a facilitator. Walter enjoys participating in a Bible study group, a choir, Men of Compassion, Black Prisoners Caucus, and the Concerned Lifers Organization.

THE ORIGINS OF WASHINGTON’S THREE STRIKES LAW

Washington’s POAA, or the Three Strikes Law as it is often called, was first introduced as legislation during the tough-on-crime era in the 1980s and 1990s and was the first three strikes law of its kind. During this time, state and federal legislatures around the country began passing bills focused on increasing sentences for violent offenders and on creating harsher punishments for drug offenses with bipartisan support.34 These bills were based on a theory of increased public safety; however, decades later, experts cite these bills as key drivers of racial inequality, mass incarceration, and militarized policing.35 After failing as an initiative in 199236 and in the Legislature in early 1993,37 Washington’s three-strikes framework became law only after the voter initiative process resurrected the ideas and proposed them directly to voters through a more coordinated campaign later that year. The initiative passed with 75.7% of the vote.38 The law has since been used to sentence a disproportionately high number of BIPOC Washingtonians to life without parole.

The Forces Behind the POAA

John Carlson, a right-wing radio commentator and former communications director for the Washington State Republican party, was responsible for envisioning the failed legislation as a ballot initiative. After losing an election for a state House seat, Carlson and others, including Ida Ballasiotes, formed a group called Citizens for Justice (CFJ). Ballasiotes became an anti-crime activist following the murder of her daughter, Diane, in 1988 by a convicted sex offender who had escaped from a downtown Seattle work release center. Among the group’s first acts was filing Initiative 590 (I-590)—a first attempt at a three strikes law—as a proposed ballot measure in 1992.39 The group did not succeed in getting I-590 on the ballot that year, but it gained the attention of the National Rifle Association (NRA)—a powerful and influential national group eager to shore up both its conservative prestige and its coffers.40

In the early 1990s, the NRA saw an opportunity in the emerging tough-on-crime conversations gaining traction across the nation––a conversation that erroneously claimed new laws were necessary to protect the public from a specific type of criminal fixated on violence and who acted without remorse.41 The NRA took notice of CFJ’s I-590 ballot initiative and, despite the measure’s failure, saw it as the lifeline it needed.

NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre boasted that “In Washington state, a citizens’ movement to put a ‘3 Strikes’ initiative on the ballot failed—until the NRA stepped in with financial, organizational, and grass-roots support.”

In 1993, Carlson’s CFJ was now operating under the banner of his conservative political think tank, the Washington Institute for Policy Studies (WIPS). Carlson had founded WIPS in the 1980s with the vision of providing the “intellectual ammunition for a conservative assault on state and regional policies.”42 Shortly after founding the policy institute, Carlson found his way onto television, pairing up with local historian Walt Crowley to conduct three-minute debates on issues of the day.43 It was during one such debate in 1988 that Carlson first suggested the idea of the POAA or, as he called it, “3 Strikes, You’re Out.”44 At this point, the NRA was eager to use the idea as a selling point. With the NRA’s support, I-590 found new life as Initiative 593 (I-593).

I-593 pushed for the same mandatory life sentence scheme that I-590 had, but this time, the initiative was infused with $90,000 in funding—approximately $195,000 in 2024 dollars—from the NRA to ensure its success.45 I-593 passed, and Washington became the first state to enact a three strikes law that imposed a mandatory LWOP sentence for third-time offenders.46 The NRA immediately mobilized behind the victory, running fullpage ads in national publications that highlighted its involvement with the law’s passage in Washington.47 NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre boasted that “In Washington state, a citizens’ movement to put a ‘3 Strikes’ initiative on the ballot failed––until the NRA stepped in with financial, organizational, and grass-roots support.”48 Within several years, nearly two dozen states had passed similar legislation.49

Initiative 593’s Messaging to Voters

The I-593 voters pamphlet played upon the public’s fear of violent crime, the perception of rising crime rates, and the impulse to “make the streets and neighborhoods safer.”50 The pamphlet stated that the initiative would bring accountability and certainty of punishment back into the legal system and would “target the ‘worst of the worst’ criminals who deserve to be behind bars.”51 The pamphlet implied that without I-593, “proven repeat offenders” would not be held accountable and would not face appropriate consequences, despite the SRA’s use of past convictions to require longer prison sentences.52

I-593 prescribed a sentence of LWOP for three commissions of a “most serious offense.” The term “most serious offense” is explicitly defined in a list that ranges broadly from reckless vehicular assault to class A felonies (e.g., Murder 1) and that notably includes any felony with a deadly weapon verdict.53 A “persistent offender” is defined as someone who has been convicted of any one of the listed offenses on three separate occasions, with at least the final conviction occurring in Washington state.54

The initiative’s stated purpose centered on principles of deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution, all presented through the lens of public safety. The proponents cited the need to lower crime rates, implement easy-to-understand sentencing, and restore trust in the criminal system. The drafters used tough-on-crime language, referring to the targeted population as “most dangerous criminals.”55

Even to the diligent voter, information about the initiative was difficult to find and understand. The 23 pages of I-593 appeared on the ballot on November 2, 1993, as an overly simplified yes-or-no question: “Shall criminals who are convicted of ‘most serious offenses’ on three occasions be sentenced to life in prison without parole?”56 To find specifics about what this meant, voters could turn to pages 14-22 of their voter’s pamphlet, where they would find the entirety of the amended Sentencing Reform Act in fine print. The explanatory statement, written by the attorney general, briefly defined “persistent offender” and defined “most serious crimes” as “essentially...all class A [and] class B felonies involving harm or threats of harm to persons.”57 Nowhere were the offenses explained in lay terms.

The initiative’s proponents were clear in their desire to eradicate the targeted people, a disproportionate number of whom were people of color, from Washington’s society—whether through locking them away until death or effectively exiling them from the state. Opening with “It’s time to get tougher on violent criminals,” the statement in support of I-593 stressed that the current sentencing scheme was too weak.58 The initiative ended with the message: “[E]ither obey the law or leave the state––for good.”59

The “Statement Against” focused on the measure’s anticipated ineffectiveness, fairness, and cost.60 It argued that because “repeat ‘serious offenders’ after middle age” are unusual, life sentences are unnecessary and simply serve to create costly geriatric wards in prisons.61 The statement further argued that the scope of I-593 was too broad, as it removed judges’ discretion and included minor events such as “bar fights” in the list of qualifying offenses.62

Racist Motivations of I-593

In his public statements in support of tough-on-crime reform, Carlson consistently used racialized messaging and proposed policies that disproportionately harm communities of color. Carlson frequently referenced rap music and its associated culture as emblematic of the problem I-593 was intended to address.63

In June 1993, six months before I-593 was placed on the ballot, and in response to a negative editorial comment that asked Carlson how many African American males between the ages of 16 and 30 he conversed with regularly, Carlson responded by saying, “I do know several African Americans. They’ve asked me to ask you why white liberals are always making excuses for [B]lack criminals who rob, steal, and peddle drugs in [B]lack neighborhoods.”64 Carlson’s opinion pieces and statements repeatedly describe violent criminals who are not properly held accountable for their actions because they are Black.65

To combat the argument that the POAA would increase the cost of incarceration, Carlson argued that the new law would have a strong deterrent effect by forcing would-be strikers to give up on crime or move out of state.66 To counter arguments that the POAA could levy heavy consequences for relatively minor offenses, Carlson intimated that such an outcome was unlikely because prosecutorial discretion would protect those individuals from being charged with a third strike.67 Carlson argued that the POAA was necessary because judges already had too much discretion, a factor that “resulted in too many perpetually violent offenders being released.”68

Narratives

Marcus Price: Righting the Ship

After serving 27 years of a life without parole sentence for being one of the first sentenced under the POAA, Marcus Price was released from prison in 2021 through clemency. But his successful transition from the controlled prison setting to a life of freedom and prosperity is entirely due to his personal drive to improve and the community support he received.

The youngest of seven children in his family, Marcus grew up on the East Coast until his early teens. Marcus considers his cross-country move a pivotal moment that launched him onto a difficult path. Like many children in new schools, he felt unprepared for different classes and a new social scene. He was discouraged when his new school put him in special education. Being labeled “disabled,” a label he didn’t identify with, made it even harder for him to find his place with his peers. He was set apart from other kids in regular classes and felt he didn’t fit in anywhere. He did not receive help for these feelings of disconnection and instead started skipping school and hanging out with older kids, experimenting with alcohol and marijuana, and engaging in risky behaviors. As a young teen, he entered a cycle of spending time in juvenile detention then going back to school where the cycle repeated itself.

Marcus’s first two strikes occurred before the POAA was passed. He was first convicted in 1985 at 16 years old for robbery. Despite his young age, Marcus was sent to adult court and sentenced to 65 months. At his release in 1990, he was 21 years old with a GED but no job skills. No reentry services were provided to help him find food, housing, or employment. Marcus describes “floating” through the next couple years of his life — living in motels or couch surfing, doing whatever he could not to burden his family.

Marcus’s second strike, in 1992, was the result of bad luck and failures of the legal system. Marcus was with friends when they were all arrested for a robbery they committed earlier in the day without him. He denied involvement and hadn’t been identified, but the police still arrested him. Though Marcus stuck by his claim of innocence, his attorney convinced him to take a special plea that allowed him to plead guilty without admitting guilt, in exchange for a lesser charge of attempted Robbery 2—a class C felony for which he spent four months in jail.

When he was released after serving time for the second strike, Marcus looked for ways to “right the ship” but did not know how to make money and resorted to crime for survival. In 1994, he received his third strike for a Robbery 1 conviction. Marcus was one of the first people to be sentenced under the POAA, despite not knowing anything about the new law. Marcus was sent to Walla Walla with a sentence to die in prison.

At one point during his incarceration, Marcus realized that others with convictions like his were not sent to adult court at age 16, and many had pleaded to non-strike offenses to avoid a POAA sentence. Marcus vowed to educate himself so that he could better understand the legal system.

Although LWOP prisoners receive the lowest priority for rehabilitative activities and resources, Marcus put himself on waiting lists and eventually got into education programs. He got a job in the book room, then later volunteered in the tool room, which sparked his interest in welding. Marcus took a vocational program and later joined the Sustainable Practice Lab and opened a welding shop in the unit. There, he met other individuals in the Redemption Project, a behavioral health program founded by Anthony Powers (now Reentry Program Director at the Seattle Clemency Project) during his own incarceration. Anthony recognized Marcus as a positive influencer who could help make the Redemption Project’s aims socially acceptable to other individuals.

Marcus was granted clemency before the removal of Robbery 2 from the strikes list was made retroactive, thanks to his own remarkable growth and the testimony of family and community members who refused to let him slip through the cracks. Today, Marcus is a thriving and engaged member of his community. Now employed at the Seattle Clemency Project, he has devoted his life to supporting others experiencing reentry. But he worries the POAA will not be sufficiently reformed. He hopes the attitude that “prisoners don’t deserve help” won’t get in the way of reform efforts that would help others benefit from the same opportunities he had.

HOW THE POAA WORKS

After Washington passed the first three strikes law in the nation in 1993,69 more than 24 states enacted three strikes laws in the following two years.70 The form of these three strikes laws varied widely. What counted as a strike offense, how many strikes were needed to strike out, or what it meant to have “struck out” (i.e., the severity of punishment) differed from state to state. Washington’s Three Strikes Law is among the most draconian because it counts less serious crimes on the list of strike offenses, and because it results in a mandatory LWOP sentence upon the third strike, regardless of the underlying offenses.

Definition of a Persistent Offender

Under the POAA, a person who commits a “most serious offense” 71 on three separate occasions is deemed to be a “persistent offender.”72 The list of crimes included in the definition of “most serious offense” is quite broad—it includes:

all class A felonies—the most serious, and generally violent, crimes;73

various class B and C felonies—less serious, may involve actual or threatened violence or bodily harm;74

attempts to commit any crime on the list of most serious offenses, and conspiracy or solicitation to commit a class A felony;75

any felony with a deadly weapon verdict, regardless of whether it would otherwise qualify as a strike;76 and

any class B felony with a finding of sexual motivation, regardless of whether it would otherwise qualify as a strike.77

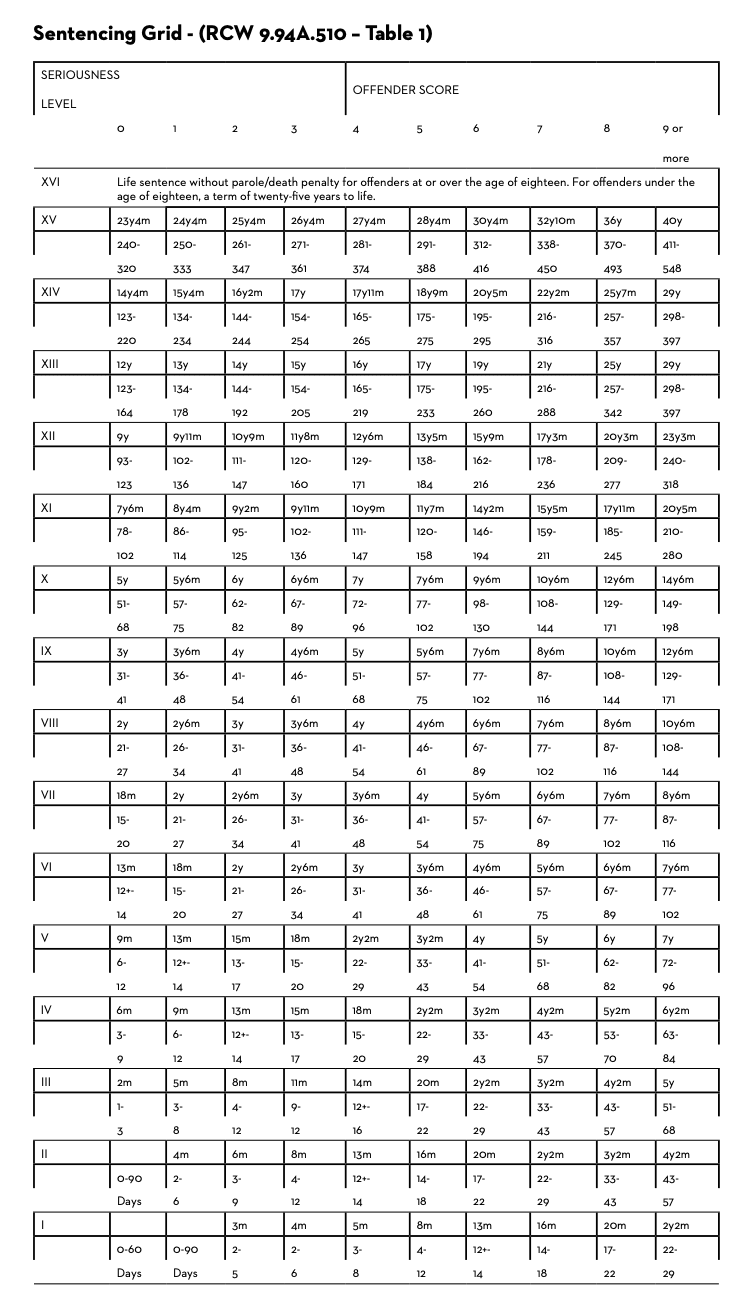

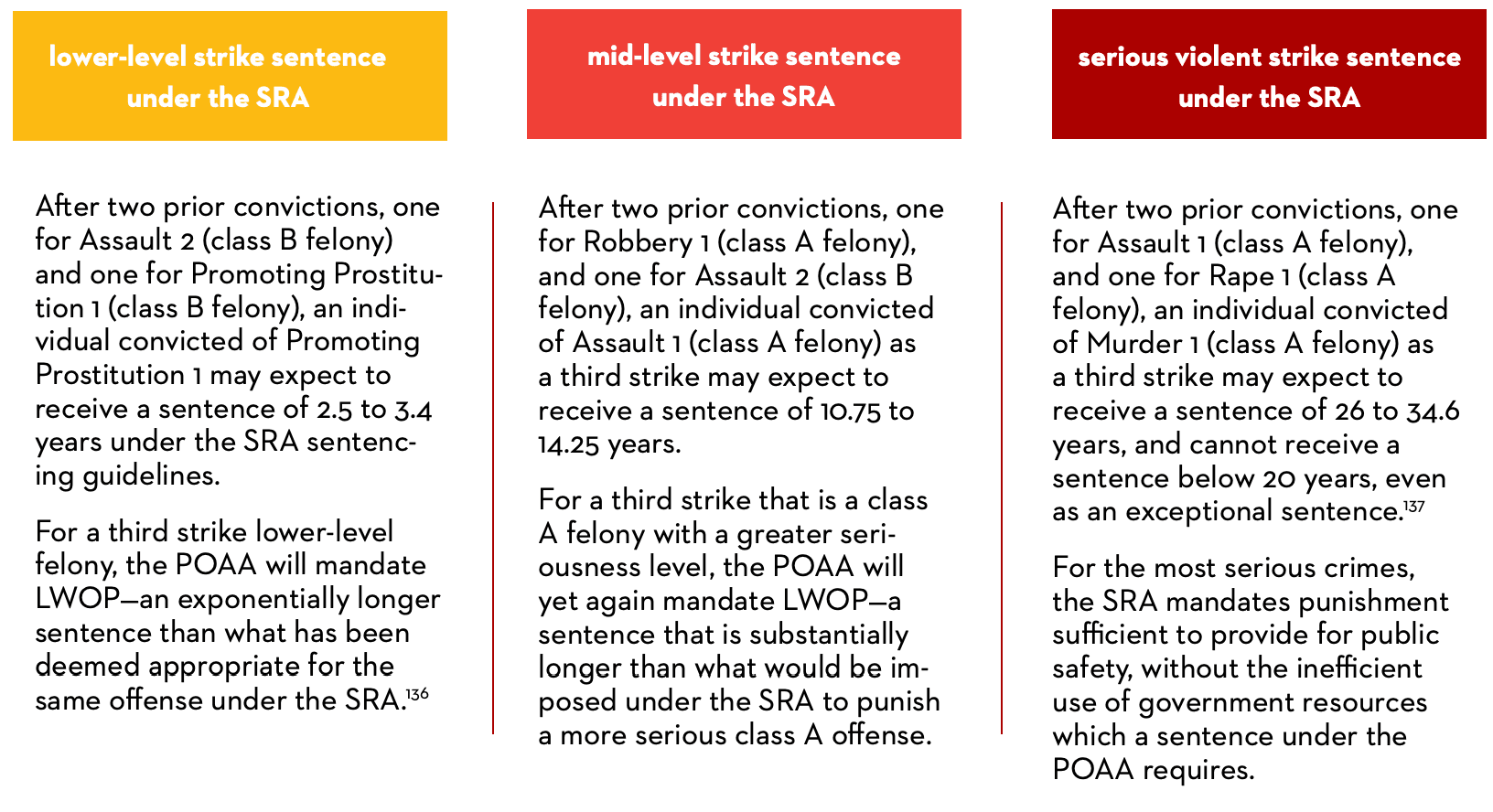

All felonies in Washington are assigned to a class that corresponds with the seriousness of the offense: class A felonies are the most serious, class C are the least serious, and class B are in between.78 When comparing the crimes that count as strikes to the seriousness levels reflected on the sentencing grid,79 they range from seriousness level IV (punishment starts at 3 months for an offender score of 0 and goes to 84 months for offender score of 9+), to seriousness level XVI, which results in life without parole.80

If a person is found to be a persistent offender, the court must sentence the person to serve life without the possibility of parole and does not have any discretion to impose a different sentence.81 Courts have characterized a life without parole sentence under the POAA as punishment only for the final offense, rather than cumulative punishment for all three strike offenses.82 Punishment for the prior strikes is imposed and served at the time of those convictions. Those serving three-strikes sentences are explicitly barred from pursuing any form of early release, even once they reach an older age with permanent or degenerative medical conditions, making it a true death in prison sentence.83

The POAA’s Broad Scope and Harsh Punishment

Aside from capital punishment, life without parole is the harshest available sentence in the United States, and in many states, including Washington, is the most severe punishment available where the death penalty is no longer legal.84 All but three states have some form of felony recidivist punishment scheme,85 and there are as many variations of which crimes are included and what punishment results as there are jurisdictions. However, among those that increase punishment for recidivist conduct, Washington is among the most severe because it is one of a handful of states that mandates LWOP for a third strike, regardless of the combination of strike offenses. Many other states with mandatory LWOP only impose the punishment for a combination of the most serious crimes, with lesser punishments indicated where one or more strike is less serious.86

The LWOP sentence mandated by the POAA is especially harsh because there is no more serious punishment allowed under Washington law. Most other states that either mandate or allow LWOP for recidivist punishment also have the death penalty for capital murder, meaning repeat offenders are not subject to the state’s harshest punishment.87 As Justice Yu noted in 2019 after the Washington Supreme Court invalidated the capital punishment statute in State v. Gregory, “Persistent offenders who have committed robberies and assaults are now grouped with offenders who have committed the most violent of crimes, including aggravated murder and multiple rapes. The gradation of sentences that once existed before Gregory have now been condensed. As a result, a serious reexamination of our mandatory sentencing practices is required to ensure a just and proportionate sentencing scheme.”88

Washington stands out among the states that impose LWOP by applying the punishment to a wider range of criminal conduct than other states with similarly harsh punishment. Washington’s POAA encompasses crimes such as Murder 1, but also extends to Burglary 1, which does not inherently include an element of violence.89 Washington’s use of Assault 290 has long been criticized as overinclusive, as it can capture everything from incidents where someone is seriously injured to minor altercations like a fist fight.91 Many other states have recidivist punishment laws that cover a wide range of crimes, but most of those states at least have an option to impose much less severe punishment by merely increasing the punishment by a prescribed measure or by allowing for parole after a minimum term of incarceration.92

The automatic inclusion of juvenile strikes93 within Washington’s Three Strikes Law is also out of step with juvenile brain science.94 Before 2013, nine states either expressly barred95 or limited96 the use of juvenile strikes. Two states have changed their laws to exclude juvenile strikes after the U.S. Supreme Court in three opinions between 2005 and 2012 acknowledged that juveniles are inherently less culpable than adults.97 In 2013, Wyoming excluded convictions of juveniles in adult courts from counting as strike offenses under its habitual offender statute.98 And in 2021 Illinois passed a law limiting habitual criminal statute to crimes committed at age 21 or older.99 By contrast, in 2023, the Washington Supreme Court held that because an LWOP sentence under the POAA is punishment for only the final strike, relying on a prior juvenile strike does not constitute cruel punishment.100

The wide net cast by the POAA, with its goal to deter repeat criminals and incapacitate the “worst of the worst” has proven unnecessary. And the public safety rationale toued by the POAA architects is nothing more than political rhetoric. Ample empirical evidence has demonstrated that life and long sentences are ineffective as crime control measures because they have no more deterrent effect than shorter sentences, and because recidivism declines rapidly with age.101 A system like the SRA, which accounts for prior criminal history in determining sentence length, already ensures public safety.

“Persistent offenders who have committed robberies and assaults are now grouped with offenders who have committed the most violent of crimes, including aggravated murder and multiple rapes. The gradation of sentences that once existed before Gregory have now been condensed. As a result, a serious reexamination of our mandatory sentencing practices is required to ensure a just and proportionate sentencing scheme.”

— Justice Mary Yu, Washington State Supreme Court

Narratives

Joshua Phillips: Growing Up Behind Bars

If you ask Joshua Phillips whether he prefers to go by “Josh” or “Joshua,” he might say “Joshua, these days.” This choice is significant, separating his life before the age of 23 from the person he has chosen to become. The quality of Joshua’s communication skills is unsurprising in someone who has taken courses in Conflict Resolution, Nonviolent Communication, Responsible Thinking, and more than 20 other courses aimed at self-improvement. He connects easily with people and goes out of his way to build community. This thoughtful, engaged 38-year-old is not likely who the voting public imagined when thinking about who would serve LWOP sentences under the POAA.

Joshua’s childhood was defined by trauma and turmoil. Throughout his early childhood, Joshua’s father continued to abuse his mother. Joshua’s mother sought help but was unable to fully remove herself from the relationship. After years of violence and terror, the day before Joshua’s fifth birthday, his father killed his mother, with Joshua and his siblings in the house.

Joshua went to live with his paternal grandmother, who offered no solace or healing, but instead subjected Joshua to physical and psychological abuse. CPS investigated multiple times but failed to intervene in any meaningful way. To make matters worse, his grandmother told Joshua and his siblings that their mother was responsible for her own death and isolated them from their mother’s side of the family, while holding their father up as a hero.

As he entered adolescence, Joshua began acting out and using alcohol and drugs. At 13, Joshua was sent to live with his grandfather in Washington, where he was incarcerated for the first time after being caught with alcohol at school. Joshua’s early teenage years were spent in and out of juvenile facilities, where he experienced physical and sexual abuse. When Joshua was released from a juvenile facility at age 17, his father, having completed his sentence for murdering Joshua’s mother, was waiting to pick him up. The first thing they did together was smoke meth, an activity which consumed the two months Joshua spent free before being arrested for his first strike.

Joshua was 17 when he was arrested for his first strike, Assault 2. He was automatically declined and sentenced in adult court. Only two months after being released, at age 19, he committed his second strike, attempted Assault 2. Shortly after being released and with minimal support, 22-year-old Joshua was again arrested on a Robbery 2 charge. While awaiting trial for this possible third strike, Joshua refused to accept a plea deal, and instead tried to get another inmate to murder a cooperating State witness in his trial. Even though it went no further than a conversation, this talk resulted in his final strike.

Joshua’s actions during the five years from his first strike to his last were characterized by youthful impulsivity—an inability to grasp the consequences of his actions on others and the repercussions he would face himself. Joshua isn’t sure whether he knew these crimes were strike offenses but is aware that the significance of a strike would not have been real to him then. Joshua spent only seven months free between his first and last strikes. While Joshua’s final strike was a class A felony, the first two were lower-level offenses, class B and C, and no one was physically injured due to any of these offenses.

Joshua is forthright when talking about the crimes he committed and makes no excuses for his past. He credits learning about restorative justice as a turning point in his personal development. He thinks deeply about the perspective of the people he has harmed, and how the harm he experienced led him to cause harm.

In 2016, his mother’s side of the family came back into his life, providing a sense of belonging and the kind of support that can motivate a person to live up to their potential. Describing the way his Aunt Nelda’s fierce advocacy led to his decision to turn away from trouble, Joshua says, “Love changed my life.” Since that time, Joshua has determinedly pursued rehabilitation. Today, he would be the first person to acknowledge that serious consequences for his actions were appropriate. Still, it is hard to see how an LWOP sentence serves the interest of justice, given the nature of Joshua’s offenses, the young age at which he committed them, and the radically different man he has become.

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN WITHOUT THE POAA?: SENTENCING IN WASHINGTON

In advocating for passage of I-593, advocates told voters that without the Three Strikes Law, “proven repeat offenders” would not be held accountable and would not face appropriate consequences.102 Nothing could be further from the truth. Removing the POAA from the criminal law would leave the rest of Washington’s Sentencing Reform Act (SRA) intact. Under the SRA, those whose third offense inflicted serious harm would receive long or life-equivalent sentences, and those whose third offense inflicted less serious harm (or no harm at all) would receive shorter sentences—consistent with the SRA’s purpose of proportionate and just punishment.103

The SRA is a determinate sentencing scheme that accounts for the seriousness of the offense and the individual’s criminal history to implement the legislature’s determination of adequate punishment.104 The sentencing guidelines hold people who have prior convictions accountable by imposing longer sentences for people who commit multiple crimes.105

History of the SRA

The SRA was enacted to address vast disparities in sentence lengths imposed under the preexisting system.106 Under the prior system, judges had broad discretion to set the maximum term at sentencing.107 And other than a few serious offenses with mandatory terms, parole boards had unrestrained discretion to determine when to release a person before the end of the maximum term, based on demonstration of sufficient rehabilitation.108 This system resulted in people convicted of the same offense serving considerably different amounts of time in prison.

The great variation in sentences under the pre-SRA system led diverse interest groups to advocate for changes to reduce disparities and clarify potential consequences for criminal activity.109 The SRA ultimately reflected a consensus of these groups with otherwise divergent interests.110

Truth in Sentencing

The drafters of the SRA embraced the concept of “truth in sentencing,” which essentially stripped judges of discretion at sentencing.111 Under the SRA, all sentences were to be determinate, meaning that the length and conditions would be known “with exactitude.”112 As a result, parole has largely been abolished.113

The SRA requires that judges select a sentence within a prescribed range based on the seriousness level of the crime and the individual’s offender score.114 SRA sentencing ranges are presumptive: judges must impose a sentence within a range unless there are substantial and compelling crime-related reasons justifying an exceptional sentence, and any deviation from the sentencing range is subject to substantive appellate review.115, 116

The SRA established a sentencing grid which ultimately controls all sentencing decisions. The grid designates 16 seriousness levels for felonies, with Aggravated Murder 1 being the only crime at the highest level. At the lowest level are minor felonies including Forgery, Theft 2, and Unlawful Use of Food Stamps.117 The sentencing grid also includes a scoring system for criminal history that assigns variable weights based on number of convictions, seriousness of the offense, similarity to current offense, and length of time between convictions.118

Seriousness level, on the Y-axis, and offender score, on the X-axis, are combined in the sentencing grid with 140 cells assigning sentences ranging from 0-60 days for a level I offense with an offender score of 0, to mandatory Life Without Parole for the level XVI offense of Aggravated Murder for any offender score.119

Stacking Sentences to Increase Punishment

The “Hard Time for Armed Crime” initiative, adopted by voters in 1994, established mandatory enhancements that further increase sentences for individuals who are convicted of felony crimes while armed with a deadly weapon.120 This law created a two-tiered system of mandatory sentence enhancements related to weapon use, anywhere between six and 60 months, depending on the type of weapon used and the seriousness of the crime committed.121 Enhancements are added to the total of the sentence for the underlying crime, multiple enhancements must be served consecutively with no time reductions for good behavior,122 and judges do not have discretion to alter the length of the enhancement or to order it to be served concurrently.123 Because of the mandatory, consecutive nature of these enhancements, their inclusion in charges can result in extremely long sentences.124

Individuals convicted of multiple serious violent offenses also face extremely long sentences because the law typically requires courts to run sentences for multiple counts consecutive to each other.125 And because the sentencing ranges for serious violent offenses usually amount to many years for each offense, stacking the sentences can easily result in decades of incarceration.

Exceptional Sentencing

Courts have limited discretion to impose a sentence either above or below the standard sentence range, if the court finds that there are “substantial and compelling reasons justifying an exceptional sentence.”126 Exceptional sentences must still be for a determinate term and cannot exceed statutory maximum sentences or fall below statutory minimum sentences, where they exist.

The court may consider specific factors, typically related to the crime, in deciding whether to impose an exceptional sentence either below or above the standard sentencing range.127 Mitigating circumstances justifying a sentence below the standard range are illustrated by non-exclusive examples in the statute, such as the victim’s participation in or initiation of the incident, crimes committed under duress, and offenses committed in response to abuse.128 A sentence above the standard range must be based on the statutory aggravating factors that the State has pleaded and proved beyond a reasonable doubt and which cause the offense to be significantly different from the “typical” crime on which the sentencing guidelines were based.129

Prosecutor Power Under the SRA

The SRA bolstered the power of prosecutors, providing them with discretion to make critical decisions, such as what crime to charge, whether to plea bargain, and when to grant a request for resentencing.130 While the stated purpose of the SRA is to “[e]nsure that the punishment for a criminal offense is proportionate to the seriousness of the offense and the offender’s criminal history,”131 in reality, prosecutors have immense power to determine the outcome in any given criminal case. By referring to the sentencing grid, prosecutors can know in advance with near certainty the sentence the court will impose based solely on the crime charged. In Washington, “it is very common to have different prosecutors in the same office make wildly different charging decisions on the same set of facts.”132 Because criminal conduct often meets the definition of various similar crimes, the prosecutor can, to some degree, control the length of the sentence through selection of which crime(s) to charge. This gives prosecutors tremendous leverage in negotiating plea deals, and in the three-strikes context can result in the difference of a standard SRA sentence and life without parole.

Further, the data presented above bears out the possibility that implicit biases of prosecutors are partially responsible for driving the observed racial disparities. Like all actors in the criminal legal system, prosecutors are also at risk of acting on implicit racial bias or personal perspectives in exercising prosecutorial discretion.133 For example, a prosecutor faced with deciding between a strike offense or a non-strike offense may unconsciously select the harsher crime based on harmful racial stereotypes associated with dangerousness and criminality.134

SRA Sentencing Examples

Determining the sentence for a third strike in the absence of the POAA requires reference to the sentencing grid, which increases punishment based on criminal history. This exercise demonstrates both that the law is overly harsh for the lower-level offenses and that the SRA results in serious punishment for the more serious and violent crimes. The three simple examples below illustrate this point.135

NARRATIVES

Orlando Ames: Showing Up

Orlando Ames remembers growing up in an environment where boys didn’t cry. Instead, they fought. But fighting was simply an outlet for emotions that could not find their own healthy expression. Ultimately, it was a lack of support and a lack of understanding of these emotions that Orlando says set him down the wrong path.

“I loved school!” he says. “I was bored in school––I got ahead of other kids. Anything I wanted to do, I could. People would say to me, ‘You’re one of the smartest people I know.’” But he still found himself in conflict: “I had anger issues,” he admits, but the tools to handle them weren’t there. “I didn’t know how to deal with things emotionally.”

Orlando was a very young man when he committed his first two strike offenses. In 1986, when he was just 18 years old, Orlando was convicted of Robbery 2. His second strike of Robbery 1 came two years later in 1988. Then, just after Washington enacted the POAA, Orlando was convicted of Assault 2. In April of 1995, he received a mandatory sentence of life without parole.

As he began serving his sentence, Orlando reflected on his life, his choices, and how, despite his incarceration, he had matured and changed. He was now 27, and he sought ways to support others in similar positions and from similar backgrounds. Because of his LWOP sentence, Orlando was ineligible to participate in many classes and programs. Despite this, he successfully petitioned to participate in the prison’s education system. He joined University Beyond Bars and the Black Prisoner’s Caucus. Orlando earned his degree and helped to build the foundation of a community that values education, giving back, and making sure no one is left behind.

“Our goal was to refuse to let anyone fail,” he says. “We studied in the yard, the gym … anywhere.” Orlando recognized that many people around him in prison were likely dealing with unresolved trauma. He remembers, “People would say, ‘He’s uneducated.’ No, it’s how you were trying to teach him. The truth is they can learn. It’ll surprise them when you see the light click on and they get it.”

Though Orlando would have been released after Robbery 2 was removed from the strikes list, he was granted clemency and released almost ten years ago. At Orlando’s clemency hearing in 2014, King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg discussed the mistaken presumption held by prosecutors when the POAA was new that they did not have discretion in charging and sentencing decisions. Had prosecutors been aware of this discretion, many individuals, such as Orlando, who had been convicted of “young man’s crimes,” as Satterberg put it, would have been treated differently.138

Orlando’s journey highlights a lack of resources, a lack of support during critical points in his youth, and a mistaken belief among prosecutors that they had no ability to take a different approach when the punishment truly didn’t fit the crime. His experiences as a young Black man in disadvantaged Seattle neighborhoods only strengthened his anger. “The streets provided me with an outlet to my frustration and pain,” he says. Today, Orlando can clearly express what would have kept him off the path to incarceration: “I wish there was someone I could have spoken to,” he says, “someone who looked like me that understood what I was going through.”

Since his release in 2014, Orlando has dedicated himself to becoming the figure that he needed when he was young. For years he has worked in the community helping those who have been in the system or who are at risk of becoming system involved. He now works as an outreach specialist, connecting with youth who need someone who can relate to the challenges and struggles they experience. “Be consistent with young folks,” he says. “[Kids] don’t have that consistent person who shows up [for them]. Even when they cuss me out, I say, ‘OK, I’ll show up tomorrow.’” Reflecting on the importance of having someone who shows up, he adds, “To understand a young person, you have to talk to them. You’re planting a seed that things can be different. I still look at my journey as something I went through. It doesn’t define me. I am not the behavior I once demonstrated.”

EFFORTS TO REDUCE THE HARM OF THE POAA

Three-strikes laws have been subject to criticism from the beginning, primarily because the sentencing schemes are often over-inclusive and not proportionate to the offenses committed. By the early 2000s, several states with three-strikes punishment schemes significantly modified their laws by reducing their severity or scope.139 In Washington, several reforms to the POAA have been attempted, but in the three decades since it became law, the removal of Robbery 2 from the strikes list (and its retroactive application) has been the only meaningful change.

Legislative Attempts at Reform

Concerns about the racial disparities created by the POAA surfaced within a decade of its passage.140 The emergence of this reality created more and more pushback against the law, including from the chairman of the Sentencing Guidelines Commission.141

Soon, legislative actions started to reflect the changing public opinion on the efficacy of the Three Strikes Law. The bill report for House Bill 1881 in 2003 was the first to expressly mention racial disparity as part of testimony in favor of removing Assault 2 and Robbery 2.142 The argument in favor of these amendments was that the POAA was meant to target the most serious, violent, and dangerous offenders. Robbery 2, as a class B felony,143 was simply not the kind of offense the law was meant to address.144 Additional testimony in favor of removing Robbery 2 through the years also addressed racial disproportionality, noting, in 2009, the “disparate effect on African Americans,” and in 2019, the “racial disparity in how the persistent offender statute is enforced.”145

Efforts to remove Robbery 2 and Assault 2 from the strikes list began in 1999 and have continued through 2021 and 2024, respectively.146 Efforts to remove Assault 2 from the strikes list have not yet succeeded. But after decades of advocacy, in 2019, S.B. 5288 successfully removed Robbery 2 from the strikes list.147 The amendment was made retroactive in 2021 through S.B. 5164,148 allowing anyone serving a three-strikes sentence based on at least one Robbery 2 offense to be resentenced.149

Notably, the Washington Association of Prosecuting Attorneys supported this change, stating that it would mitigate the disparate impact of the POAA on communities of color and save costs to the state overall.150 The 2019 bill, like the earlier bills proposing removal of Robbery 2,151 had support from prosecutors.152 King County Prosecuting Attorney, Dan Satterberg, who had been vocal about concerns with aspects of the three strikes regime for many years, said in 2008: “before three strikes your third robbery 2 would net you about 18 months in prison. Now it’s life.”153 Then, in 2013, Satterberg said: “[I]t is in the interest of justice not to throw away the key on those who committed a robbery in their 20s and who are now in their 40s.”154

John Carlson has strenuously opposed efforts to amend the law at the Legislature. Through racially coded language, Carlson stated in 2011 that the Three Strikes Law targeted “two types of criminals: (1) dangerous thugs and (2) those who commit less-severe yet more numerous offenses over time.”155 But the Legislature’s action in undoing the arbitrary, disproportionate, and devastating impact of including Robbery 2 in the Three Strikes Law sends a clear message about how it is perceived by the public.156

More recently, efforts in both the courts and the legislature have focused on removing juvenile strikes from the POAA. Stakeholders in the criminal legal system now recognize the neurobiological differences of the developing brain that make children less culpable than adults and afford them greater constitutional protection from disproportionate punishment.157 But in 2023, the Washington Supreme Court avoided ruling on the constitutionality of juvenile strikes in State v. Reynolds by reasoning that the POAA punishes only the third strike, and is not technically punishment for earlier strikes, including those committed under age 18.158 During the 2024 legislative session, in response to Reynolds, Senator Frame introduced S.B. 6063. This bill would have prevented the use of juvenile strikes and allowed those already serving life sentences based on juvenile strikes to seek resentencing. The bill made it out of committee but failed to make it to the floor for a vote.159

Prosecutors’ Recognition of Their Power to Address Past Harm

One of the first things former King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg did after taking office in 2008 was to pull the case files of individuals sent to prison for life without the possibility of parole under Washington’s three strikes regime and assign three deputies to review the cases.160 Fifteen years had passed since the first individuals were sentenced under the POAA, but Satterberg made these closed cases a priority because he believed “[s]ome of these cases d[id]n’t deserve a life sentence.”161 In 2011, Satterberg backed a bill in Olympia to reform the Three Strikes Law by establishing parole eligibility after 15 years for those who did not have any strikes that were class A felonies or sex offenses.162 Though that bill did not pass, Satterberg’s commitment to addressing injustices in specific cases continued. By 2014, Satterberg had testified on behalf of at least six individuals with three-strikes sentences in front of the Washington State Clemency and Pardons Board.163 While testifying on behalf of Orlando Ames, Satterberg requested a clemency recommendation to “help me reconcile the charging practice in the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s office, which has significantly changed from the early days of three strikes implementation.”164

Though they are the exception rather than the rule, a few other prosecutors in Washington State have started to follow Satterberg’s lead. Former Snohomish County Prosecutor Adam Cornell believes the tough-on-crime ethos of past decades violates an “evolving standard of decency,” and former Clark County Prosecutor Camara Banfield165 wonders, “[was] the harm that great that you actually should take someone’s liberty away for the rest of their life?”166 Pierce County Prosecutor Mary Robnett began a review of eighty-nine cases after taking office in 2019 because of her concern about the law.167

These Washington prosecutors are not alone. Prosecutors from across the country have joined together to address their role in “sentencing second chances and addressing past extreme sentences.”168 In 2021, Fair and Just Prosecution published a joint statement signed by more than fifty prosecutors from all over the country, calling on their colleagues to join them “in adopting more humane and evidence-based sentencing and release policies and practices.”169 While highlighting the unique position of prosecutors in prosecuting and charging decisions, the statement acknowledged “[w]hile prosecutors and judges of decades past may have pursued and imposed harsh sentences with the misguided belief that certain individuals were incapable of rehabilitation, there is simply no justification for maintaining those sentences when a person demonstrates that the opposite is, in fact, true.”170 This statement exemplifies a changing tide in how prosecutorial discretion can and should be used.

In 2020, Washington passed into law prosecutor-initiated resentencing, stemming from Senate Bill 6164.171 The law allows prosecutors to petition a court to resentence an individual “if the original sentence no longer serves the interests of justice.”172 Rather than giving individuals serving sentences the power to go directly to the court, the Legislature bolstered the prosecutor’s power, providing another discretionary vehicle “to reevaluate a sentence after some time has passed” to ensure sentences remain proportional, uniform, and advance penological goals for public safety.173

However, this new law has fallen short in its implementation. For the law to be an effective tool, prosecutors must use it. Preliminary data gathered by the Washington Defender Association indicated that only about a third of Washington’s 39 elected prosecutors had sought resentencing as of August 2023, and only three counties had filed petitions in five or more cases.174 Further data gathered through public disclosure requests and an informal survey by Pierce County Prosecutor Mary Robnett’s office suggests that the law has been used “sparingly or not at all.”175 And various prosecutor’s offices have taken the position that they are not authorized to use this process to address mandatory sentences such as those imposed under the POAA.176

Second Look Reforms

As state governments and communities have begun to question the efficacy of three strikes laws, second look sentencing reforms have gained popularity as a way to preserve the regime but create some relief. The American Law Institute first added a second look sentencing provision to the Model Penal Code in 2008.177 The most recent model language suggests allowing an individual to petition a court for a sentence review after 15 years in prison, or after 10 years in prison if the person was under 18 at the time of the offense.178