Abstract

Federal and state court decisions over the past year are reshaping the contours of juvenile justice litigation. At the federal level, the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Jones v. Mississippi left intact the Court’s current commitment to treating age 18 as the dividing line between youth and adult criminal sentencing. If a youth commits a crime at age 17 years, 364 days, 23 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds old, that youth cannot be put to death or receive mandatory life without parole (LWOP). One second later, these constitutional protections disappear. Calling into question this line drawing, litigants across the country are actively leveraging neuroscientific research to argue that emerging adults ages 18 through early 20s should receive the same constitutional protections as those under 18. While federal courts have not been receptive to this argument, some state courts are. Groundbreaking recent cases in Washington, Illinois, and Massachusetts state courts may signal a potential path forward. In light of these many recent developments, this Essay provides the first empirical analysis of how courts are receiving the argument to raise the age for constitutional protections and introduces a publicly accessible, searchable database containing 494 such cases. The data suggest that at present, Eighth Amendment arguments to categorically extend federal Miller protections to those 18 and above are unlikely to win. At the same time, however, state constitutions and state-level policy advocacy provide a path to expand constitutional protections for emerging adults. We discuss the implications of these trends for the future use of neuroscientific evidence in litigation concerning the constitutionality of the death penalty and LWOP for emerging adults. As this litigation moves forward, we recommend further strengthening connections between litigants and the scientific and forensic communities. Whether at the state or federal level, and whether in courts or legislatures, the record should contain the most accurate and applicable neuroscience.

INTRODUCTION

emerging. Adj. starting to exist, grow, or become known1

In 1999, five youths—ranging from ages 15 to 19—participated in the carjacking, kidnapping, and murder of two youth pastors in Texas.2 All five were convicted of homicide,3 but at sentencing, their paths diverged.4

Brandon Bernard (age 18 at the time of the offense) and Christopher Vialva (age 19 at the time of the offense) were both sentenced to death.5 Vialva was executed on September 24, 2020,6 and despite a high-profile clemency campaign, Bernard was executed on December 10, 2020.7 Tony Sparks (age 16 at the time of the offense) was initially sentenced to life without the possibility of parole (LWOP), but in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling in Miller v. Alabama,8 his sentence was reduced to thirty-five years.9 Christopher Lewis (age 15 at the time of the offense) and Terry Brown (age 17 at the time of the offense) were both sentenced to twenty years and four months’ imprisonment.10 Brown was released in January 2020, mere months before Bernard, his childhood best friend, was executed.11 On the day Bernard was executed, Brown hugged his mother, prayed for the murder victims, and cried.12

The differing paths of these five youth illustrate a bright line currently drawn by the United States criminal legal system: youths who commit a crime when they are 17 years, 364 days, 23 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds old cannot be put to death or receive mandatory life without parole.13

One second later, these constitutional protections disappear. This line was drawn in part based on scientific research on the behaviors and brains of adolescents, which was included in various briefs and cited by the United States Supreme Court in a series of cases in which the Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the death penalty for those under age 18 at the time of their capital offense;14 prohibits life without the possibility of parole for non-homicide offenders under age 18 at the time of the offense;15 and prohibits mandatory LWOP for those under age 18 at the time of their offense, even for homicide offenses.16 These cases “establish that children are constitutionally different from adults,”17 specifically for mandatory LWOP sentences. The Court’s recent decision in Jones v. Mississippi18 retained the Court’s previous determination that “children are constitutionally different from adults for sentencing purposes,”19 but held that, in a sentencing proceeding to determine whether the defendant should get life with parole, Miller and Montgomery v. Louisiana20 do not specifically require a “separate factual finding of permanent incorrigibility.”21

The question now arises: In light of a recent growing evidence base in developmental neuroscience about the still-maturing brains of emerging adults, should youth ages 18 to early 20s receive the same constitutional protections as those under the age of 18? While the law retains a bright line at age 18, before which mandatory LWOP may not be imposed, recent developments in neuroscience increasingly show that brain circuitry relevant to decision-making and culpability continues to develop in significant ways through an individual’s early 20s.22 This science has been persuasive to some legal actors. For example, in the Brandon Bernard case discussed above, one of the prosecutors on his case later publicly supported Bernard’s appeals for a stay of execution, noting recent advancements in developmental science suggesting that there are no meaningful distinctions between the brains of 17- and 18-year-olds.23

In this Essay, we provide the first examination of cases in which neuroscience is being deployed to argue that the death penalty and mandatory LWOP should be constitutionally prohibited for emerging adults. We focus here on the use of neuroscience to argue for the categorical application of Miller to cases involving emerging adults, not necessarily the use of neuroscience for mitigation or other purposes in individual cases. As we discuss later, using brain evidence for extending the adolescent category in juvenile courts, LWOP, and prison conditions is not the same as using brain evidence in an individual case.

Our analysis finds that litigants regularly argue that drawing the line at age 18 is inconsistent with current neuroscientific consensus.24 It is clear, however, that courts are presently unreceptive to raising the age for Miller protections. In our database, the record for Eighth Amendment challenges is 0 wins and 494 losses.25 One temporary win, in federal district court, was subsequently vacated and remanded at the appellate level.26 A second win, in the Illinois Supreme Court, was made on the basis of a state constitutional provision rather than the Eighth Amendment.27

Courts are rejecting attempts to extend Miller both on the basis of stare decisis and because of a perceived lack of legal relevance of advances in neuroscientific knowledge about the emerging adult brain.28 Courts consistently point out that because the Supreme Court’s constitutional line drawing at age 18 was based in large part on societal norms reflected in legislative determinations defining juvenile and adult criminal jurisdiction, rather than exclusively on the neuroscientific understanding of the developing brain, new arguments premised on neuroscience are unpersuasive.29 While the Supreme Court’s recent verdict in Jones would seem to signal that it is unlikely the Court would expand protections for youths 18 and older, developments at the state level suggest that challenges based on state constitutional provisions may be more successful.30 We discuss the implications of these trends for the future use of neuroscientific evidence in litigation concerning the constitutionality of the death penalty and LWOP for emerging adults.

The Essay proceeds as follows. Part I briefly reviews scholarly literature scrutinizing age 18 as the boundary line for constitutional protections. Part II introduces the methods we used to identify and analyze cases that utilize neuroscience evidence to try to extend Miller and illustrates general trends and notable exceptions in courts’ responses to this evidence. Part III discusses the implications of these results for the future use of neuroscience evidence in law and policy concerning the sentencing of emerging adults.

I. LINE DRAWING AT AGE 18: CONSENSUS AND CONFLICT

Current neuroscientific consensus is that age 18 is not a magic number in the development of legally-relevant brain circuitry.31 Cross-national behavioral evidence suggests sensation-seeking behavior peaks around age 19, with self-regulation developing through the mid-20s.32 However, the concept of brain maturity remains “fuzzy,” and “there is little agreement among scientists on what properties of a brain should be evaluated when judging whether a brain is mature.”33

In Roper v. Simmons, Justice Kennedy recognized this fundamental tension: “[t]he qualities that distinguish juveniles from adults do not disappear when an individual turns 18.”34 Just as “any parent knows” that 16-year-olds are not as mature as adults, parents also know that their child’s 18th birthday does not mark the end of development.35 This understanding is

not limited to parents. Car rental companies and insurers, for instance, charge significantly higher rental prices for rental drivers under age 25.36 As one scholar observed, “[p]arents, neuroscientists, and car rental companies appear to be on the same track here; it is the criminal justice system that is out of sync.”37 While there is a general agreement that drawing a bright line at age 18 needs to be reexamined, it is less clear what a viable path forward looks like in the context of criminal sentencing. The primary, and not necessarily mutually exclusive, recommendations are: (1) to extend constitutional protections already afforded to juveniles (application of LWOP) to encompass young adults at least to age 21 and perhaps to age 25; (2) to raise the age limit for juvenile courts; (3) to create specialized young adult courts and diversion programs; and (4) to treat young adults differently within existing systems.38

In this Essay, we focus on the first possibility: extending constitutional protections for LWOP and the death penalty to those older than age 18.

II. ANALYZING NEUROSCIENCE-INFORMED MILLER CHALLENGES

The Supreme Court decided Miller on June 25, 2012.39 As of this writing, over 5,000 court decisions have cited Miller.40 This Essay examines a subset of these cases in which litigants use neuroscientific evidence to argue that Miller’s holding should be extended to those age 18 and older.41 From an initial finding of 5,384 cases, we established a database of 494 cases that substantively discuss neuroscience and involve defendants aged 18 or older at the time of their offense.42 Using a sixteen-case convenience sub sample from this database, we then more deeply investigated how the most recent litigants are employing neuroscience.43

Our analysis indicates that federal courts have refused to extend Miller to defendants age 18 and above. Despite litigants’ regular use of neuroscientific arguments, none of the 494 petitions identified in our database were ultimately successful.44 In this Part, we analyze (A) trends over time and across geography, (B) differences in the age of the defendant at the time of the offense, (C) the specific neuroscientific evidence proffered by litigants, and (D) our core concern: how courts respond to these arguments that include an introduction of neuroscientific evidence.

A. Distribution of Cases Across Time and Geography

1. Time Distribution

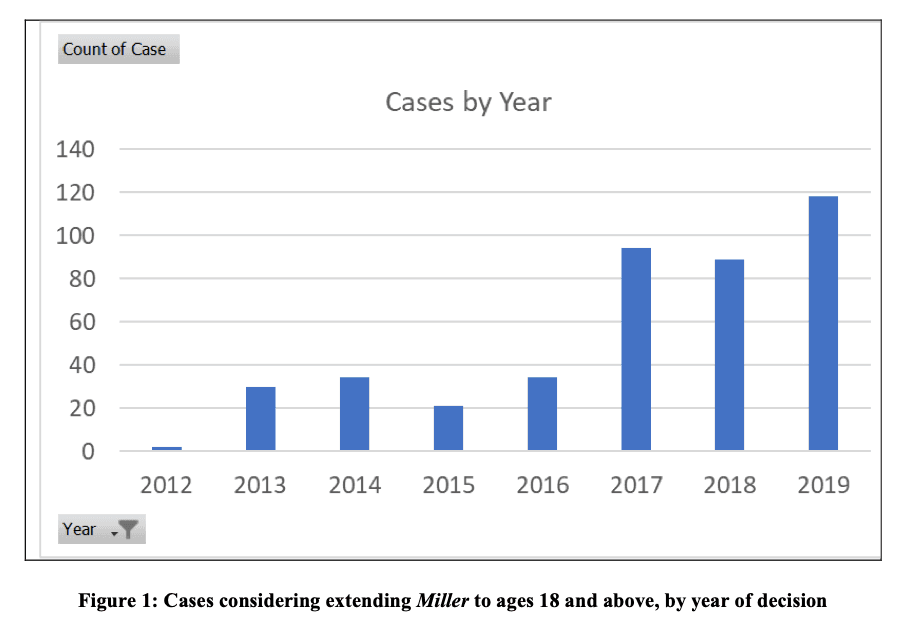

Between 2013 and 2016, courts considered in each year an average of thirty cases attempting to extend Miller to defendants age 18 and older.45 In January 2016, the Supreme Court ruled that Miller applied retroactively, which opened the doors for additional litigants.46 The number of annual cases in our database tripled after 2016, and although our database ends in 2020, it appears that cases continued to be plentiful in 2021.47 The appellate process may delay this timeline. In many states, lower level court cases are not published on Westlaw, the source of our data. Lower court cases in these states would not appear in our database unless and until they were appealed. For example, a petition filed in a Pennsylvania county court in March 2016 did not appear in our database until a verdict was reached on appeal in October 2017. More broadly, increases in the number of petitions may not be reflected in our data until several months or even years later.

2. Geographical Distribution

Nearly half (47%) of the cases considered are from Pennsylvania. The principal reason for this trend is that, as noted in oral argument in Miller, Pennsylvania historically had been one of the states with the largest numbers “of juveniles serving life without parole by a huge margin.”48 The higher number of cases from Pennsylvania may also be a result of the state’s sentencing procedures. Pennsylvania requires defendants to file a Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) petition.49 Allowing defendants to act on their own initiative provides a standard procedure for defendants aged 18 and older to argue that Miller should apply in their circumstance, likely increasing the number of petitions filed.

The substantial number of cases from Pennsylvania may also be related to a growing movement towards youth criminal justice reform within the state.50 After Montgomery, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office established a specialized “Lifer Committee,” to make concerted resentencing efforts in the state.51 As of December 2019, Pennsylvania had resentenced more juvenile LWOPs than any other state.52 A growing coalition of engaged legal actors—including the Juvenile Law Center, Pennsylvania Innocence Project, federal defenders’ offices in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, advocates in the Philadelphia defender’s office, an array of anti-death penalty advocates, and the recently founded abolitionist Amistad Law Project—have further produced, as described by attorney Marsha Levick, an “energy point[ing] to a robust interest in reducing incarceration and extreme sentencing” in Pennsylvania.53 The Pennsylvania outlier cases are an important reminder that although we discuss national trends in this Essay, state-specific developments will vary.

B. Age of Defendant at Time of Offense

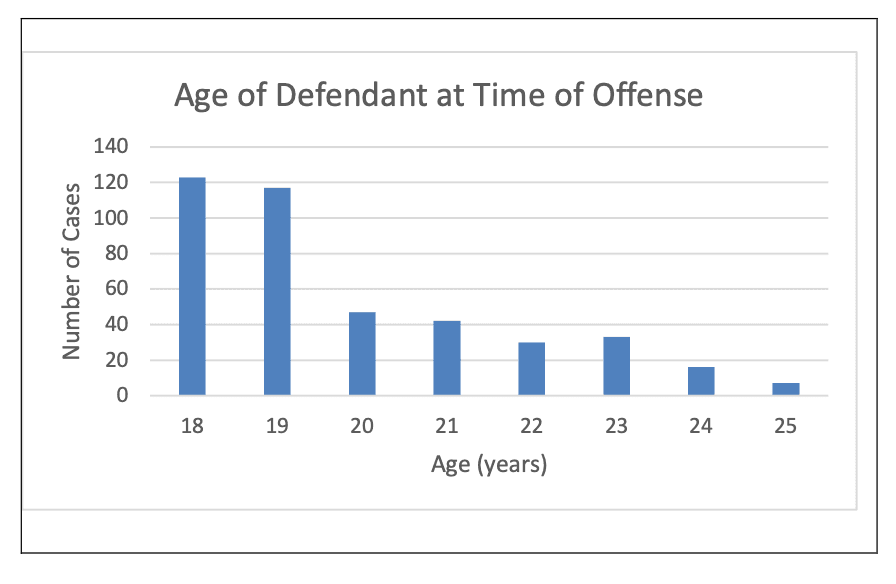

The majority of cases in our database involve defendants who were ages 18 or 19 at the time of their offenses. The number of cases drops off approaching age 25, with some outliers (Figure 2).54

C. How Litigants Use Neuroscience

In general, petitioners used neuroscientific evidence to bolster the assertion that Miller should be extended to cover petitioners aged 18 to mid 20s because the brain continues to develop in critical ways through the mid 20s.55 However, the specific neuroscience evidence cited in these cases varied widely. In the sixteen-case subset for which we examined case briefs, we identified 108 unique scientific citations. These citations all generally concerned the developing brain, but some were publications in law, others in science, and still others were commentaries. Only 6 of these 108 publications were cited in 4 or more cases.56 The most commonly cited source of neuroscientific evidence was a Fordham Law Review article57 that analyzes neuroscientific and psychological research on young adults and concludes that the period between adolescence and adulthood “can be understood as a transitional stage” different from both adolescence and adulthood.58 Petitioners cited evidence from the article suggesting that the brain continues developing from age 18 through the mid-20s and that the brains of individuals in this age group typically share important similarities with the adolescent brain.

For example, one petitioner submitted an amicus brief that cited the Fordham Law Review article to argue that “eighteen year olds [sic] ‘are not fully mature adults’ but rather are more like adolescents under the age of eighteen in three essential ways”: their propensity for risk-taking, their susceptibility to peer pressure, and their prospects for rehabilitation.59 Other petitioners cited a variety of sources, from scientific journal articles to news articles, to form roughly the same general argument: The young adult brain shares similarities with the adolescent brain that require the extension of Miller protections to those above 18 years old.60

Follow-up interviews with attorneys and legal clinical supervisors who have regularly utilized neuroscientific evidence in this type of litigation suggest that there is currently no centralized resource through which to access a consolidated list of relevant and up-to-date scientific citations.61 Moreover, the sources referenced vary in terms of comprehensiveness, timeliness, and scientific rigor.

D. Court Responses to Neuroscientific Evidence

We relied on the full database of 494 cases to analyze court responses to claims that Miller should be expanded to include young adults.62 In all of these cases, the courts rejected the petitioners’ arguments that Miller should be extended on the merits. Most courts simply stated that Miller only applied to LWOP for those below 18 years old, so the case did not govern the sentencing of anyone 18 or older.63

A few courts offered additional justification for their refusal to extend Miller. For example, in Zebroski v. State,64 the court refused to extend Miller despite the petitioner’s neuroscientific evidence for two reasons. First, the Supreme Court in Roper decided to draw a line at 18 despite acknowledging that the brain does not finish developing at exactly 18 years of age.65 Second, the Supreme Court did not base its decisions in Roper, Graham, and Miller purely on “the most advanced” neuroscience available: “The choice of age 18 was not . . . an attempt to identify . . . the developmental boundary between childhood and adulthood. It was based on societal markers of adulthood—the age at which the states allow individuals to ‘vot[e], serv[e] on juries, [and] marry[] without parental consent.’”66 Because the Supreme Court’s line drawing at age 18 had been grounded at least partially on societal norms, courts found new arguments premised exclusively on neuroscience largely unpersuasive.

Courts sometimes ruled against petitioners for reasons not directly related to the strength of their arguments to extend Miller, such as lack of timeliness.67 Other judges made institutional competence arguments, concluding that while courts were bound by precedent, legislatures should consider whether to reform the law based on neuroscientific evidence about the young adult brain.68

A few courts left open the possibility that Miller might apply beyond the defendant’s 18th birthday, but still refused to grant such relief. One court agreed with a petitioner that “the legal definition of ‘youth’ is expanding,” and therefore it would seem a “short step” to extend Miller’s protections to 18-year-olds.69 It nevertheless declined to take the “greater leap” of applying Miller’s protections to a defendant who was 23 years old at the time of his offense and whom the court did not believe actually exhibited the youthful qualities identified in Miller.70

The most notable exception to the general trend occurred in Cruz v. United States,71 a Connecticut district court case concerning the application of Miller to 18-year-olds.72 The court noted the consistency of the Supreme Court’s restriction of Miller to those under 18, but asserted that no precedent barred it from extending Miller to those 18 and older.73 The court then accepted the petitioner’s argument that both national and neuroscientific consensus supported Miller’s extension to defendants 18 years old at the time of their crimes.74

As for evidence of national consensus, the district court weighed legislative enactments regarding the sentencing of young adults,75 actual sentencing practices,76 and general trends of where society draws the line between child and adult.77 With respect to scientific consensus, the district court based its decision heavily on the expert testimony of Dr. Laurence Steinberg, though it also considered various scientific articles submitted by the petitioner and his expert witness.78 Ultimately, “relying on both the scientific evidence and the societal evidence of national consensus,” the district court concluded “that the hallmark characteristics of juveniles that make them less culpable also apply to 18-year-olds. . . . The court therefore holds that Miller applies to 18-year-olds . . . .”79 In a telling, and not unexpected, development, Cruz was subsequently overturned on appeal.80

The Illinois state constitution’s proportionate penalties clause also provided an alternative path for petitioners to succeed in raising a Miller challenge. In the companion cases of People v. Johnson81 and People v. Ruiz,82 which concerned group crimes committed by defendants of varying ages, an Illinois state court allowed the defendants (aged 18 and 19 at the times of the crimes) to file successive post-conviction petitions on these grounds (petitions which would otherwise be barred):

[Petitioners] have made prima facie showings in their pleadings that evolving understandings of the brain psychology of adolescents require Miller to apply to them. Their petitions and their counsel on appeal urge that we account for the emerging consensus that the development of the young brain continues well beyond 18 years, the arbitrarily demarcated admittance to adulthood for those arrested and entering our criminal law system.83

Aside from these state court cases that dealt with procedural issues and the ultimately overturned temporary win in Connecticut federal district court, none of the petitions we evaluated were successful in convincing courts to extend Miller protections to young adults 18 and above.

III. DISCUSSION: THE PATH FORWARD

Despite litigants’ regular use of neuroscientific evidence about the emerging adult brain, federal courts are not yet persuaded that Miller should be extended to defendants age 18 to early 20s. We do not conclude, however, that ongoing litigation efforts are in vain.

First, we are focused in this Essay exclusively on the use of neuroscientific evidence to support Eighth Amendment (and state constitutional) arguments concerning emerging adults ages 18 through early 20s as a class. But neuroscience also has a role to play in the arguments that individual young adults make in challenging their lengthy sentences. Translating group-averaged scientific data to individualized adjudication is a well-known challenge in the law.84 In the context of juvenile sentencing since Miller, forensic experts Thomas Grisso and Antoinette Kavanaugh have proposed an individualized approach,85 but courts have offered little “guidance regarding application of the Miller factors or other developmental evidence to examine mitigation in individual cases.”86 Emerging adult cases suggest that further work is needed to develop evidentiary records that are sufficiently individualized.

For instance, in October 2021, the Illinois Supreme Court considered the case of Antonio House, who was sentenced to life as a 19-year-old for his involvement as a lookout in a 1993 double homicide.87 House argued that he was entitled to a resentencing hearing because his mandatory life sentence violated the proportionate penalties clause of the Illinois Constitution as applied to him.88 In remanding the case back to the circuit court to further develop the record, the Illinois Supreme Court found that House failed to:

[P]rovide or cite any evidence relating to how the evolving science on juvenile maturity and brain development applies to his specific facts and circumstances. As a result, no evidentiary hearing was held, and the trial court made no factual findings critical to determining whether the science concerning juvenile maturity and brain development applies equally to young adults, or to petitioner specifically, as he argued in the appellate court.89

Similar as-applied challenges will require individualized evidence and this will in turn require collaboration between the forensic and scientific research communities. At the Center for Law, Brain & Behavior (CLBB), we foster such collaboration through programs such as the Federal Judicial Center-CLBB Workshop on Science-Informed Decision Making.90

Second, and returning to class-based bright line challenges, it should be recognized that high impact litigation often requires many years of challenges to succeed and that even unsuccessful lawsuits can shift perception over time.91 Instead, our data indicate the need for more accessible neuroscientific evidence and an increased emphasis on state court litigation and complementary policy and legislative reform.

As impact litigation efforts continue, it is clear that there is a need for a more focused, thorough, and sophisticated application of neuroscientific evidence. As suggested by our review of briefs in select cases, litigators do not have access to a “go-to” set of scientific resources. Scientific discussion in the cases analyzed often failed to tackle nuances such as the challenge of drawing individual inferences about a particular petitioner from group averaged neuroscientific data.92 In addition, much of the scientific literature cited in these briefs was published before 2012, which dampens the case that “new” science (unavailable to the Miller court) justifies raising the age. A comprehensive review of the relevant scientific literature, summarized in an accessible manner for lawyers and judges, would be highly useful for the field. One step in this direction is a recent CLBB Guide,93 but more applied tools—such as model briefs—are also needed.

Of course, even with stronger scientific evidence and more precise arguments, future federal litigation faces steep odds. This is particularly true after Jones, which signaled the Supreme Court’s current reluctance to reduce punishment for juveniles despite leaving much of the existing precedent nominally intact. Given our review of emerging adult Miller cases to date and the current federal court climate, arguments predicated at least partially on state constitutional grounds may provide litigants with a more productive way forward. Groundbreaking recent cases in Washington, Illinois, and Massachusetts state courts together open up a potential path to navigate the future landscape of emerging adult justice. These cases may be highly influential in turning the tide of public perception.

In 2021 the Washington Supreme Court extended Miller to ban automatic life without parole sentences for 18- to 20-year-olds under the state constitution’s bar of “cruel punishment.”94 In a 5-4 decision, the court granted two petitioners, aged 19 and 20 at the time of their offenses, a new sentencing hearing, concluding:

Modern social science, our precedent, and a long history of arbitrary line drawing have all shown that no clear line exists between childhood and adulthood . . . . [W]hen it comes to mandatory LWOP sentences, Miller’s constitutional guarantee of an individualized sentence—one that considers the mitigating qualities of youth—must apply to defendants at least as old as these defendants were at the time of their crimes . . . . . . Just as courts must exercise discretion before sentencing a 17- year-old to die in prison, so must they exercise the same discretion when sentencing an 18-, 19-, or 20-year-old.95

Arguments such as these founded on state constitutions may be particularly effective in situations involving relative culpability for group offenses. Proportionality in sentencing may mean something different when two similarly situated defendants receive drastically different sentences for the same crime exclusively on the basis of their age. States such as Illinois, as discussed above, have already extended Miller in cases involving multiple defendants of different ages at the time of a group crime.96

Similarly, in 2020, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court acknowledged that neuroscientific advancements necessitated reevaluation of the policy of sentencing young adults to LWOP,97 and remanded the case to the lower court for examination of neuroscientific evidence specific to the defendant.98 As of this writing, Massachusetts is again considering whether to ban LWOP sentences for defendants aged 18 at the time of their offense.99

In the case at hand, two youths were convicted of homicide. One of them was ten days younger than 18 at the time of the offense and will become eligible for parole after serving a fifteen-year sentence. The other was only eight months older, but received life without the possibility of parole.100

Their case may have profound ramifications—both for the upwards of two hundred people serving LWOP sentences for crimes committed as young adults in Massachusetts and for litigants and courts across the country following these developments.

In addition to litigation in state courts, state legislatures and local courts are considering (and in some cases implementing) reforms aimed at young adults. For example, commentators in some states have suggested that young adults should be spared permanent criminal records to “facilitate their access to education, employment, and housing” after release.101 Legislative reforms are also underway, such as expanded parole eligibility for those incarcerated for crimes they committed as young adults. California, for instance, grants special parole hearings for those who are serving long prison sentences for qualifying crimes they committed before the age of 26. At these hearings, the parole board must consider “the diminished culpability of youth” and provide a meaningful opportunity for the individual to obtain release.102 The hearings are set at a fixed date during the individual’s incarceration, based on both the length of the underlying sentence and the defendant’s age at the time of the offense, and thus may allow for earlier parole eligibility.

How state and local policies should optimally respond to the unique needs of emerging adults remains contested, even amongst experts.103 At the core of the policy challenge is that emerging adults are neither young children nor fully formed adults.104 It is beyond the scope of this Essay to lay out a policy prescription for justice-involved emerging adults, and there is a concern that leaving reform to the states could result in even worse treatment for emerging adults depending on a legislature’s priorities. In thinking about potential paths forward, we recommend to readers the policy analyses conducted by the Emerging Adult Justice Project at Columbia University.105 In particular, the collaborative Emerging Adult Justice Learning Community provides a promising model for researchers, practitioners, and youth themselves to co-develop innovative solutions.106

Some states have modified the structure of their criminal court systems to better respond to emerging adults. In 2018, Vermont passed legislation that would extend juvenile courts’ jurisdiction for qualifying crimes through age 19 by 2022.107 Lawmakers in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, and California pushed to do the same.108 Such efforts have successfully raised juvenile jurisdiction through age 18 in New York, as well as in Michigan.109 A Department of Justice research committee has recommended raising the minimum age of criminal court jurisdiction to age 21 or age 24.110 Relatedly, some have proposed specialized young adult courts, which would focus on rehabilitation in light of evidence of young adults’ ability to change,111 and could in theory apply less harsh sentences than adult courts.112

Whether these are effective reforms remains to be seen. But what does seem clear is that reforms within the criminal legal system alone will not be sufficient. A recent review of the literature on emerging adults suggests the importance of community-based resources to help at-risk and justice involved emerging adults achieve employment, education, housing stability, and healthy relationships.113 The Juvenile Law Center similarly emphasizes the need for other systems of support beyond the criminal legal system.114 The Justice Policy Institute also looks beyond the traditional criminal legal system, and finds that an “improved approach to young adults should be community-based, collaborative, and draw on the strengths of young adults, their families, and their communities.”115 For example, San Francisco’s Young Adult Court (YAC) provides employment, housing, and educational support to emerging adults charged with crimes, and it was established after then-district attorney George Gascón attended a lecture on brain development.116 The YAC emphasizes the still-developing brains of the young adults accused of violating the law, and provides court staff with training on recent neuroscience.117 Upon successful completion of the program, which usually lasts ten to eighteen months, many young adults’ felonies are dismissed or reduced to misdemeanors.118 In 2020, a Massachusetts county created a similar program modeled after the YAC,119 and similar young adult courts have been established in Orange County, California,120 Cook County, Illinois,121 Omaha, Nebraska,122 Brooklyn, New York,123 and Niagara County, New York.124 On a national scale, the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Justice have jointly funded the Young Adult Diversion Project since 2017. The program aids sixteen state and local partners in providing young adults ages 16 to 24 with alternatives to prosecution and incarceration.125

State-level litigation and policy developments, such as the ones we review here, indicate a growing willingness to consider the emerging adult category as one that deserves special consideration in the criminal legal system.

CONCLUSION

To quote the Supreme Court, “any parent knows” that kids are different from adults.126 But for those in the middle—emerging adults—a growing body of behavioral and neuroscientific research suggests an important new insight on developmental trajectories. Even though we may label those 18 and above as “adults” in some contexts, the decision-making of emerging adults, ages 18 to 25, remains distinct from those who are older. Evidence of this new scientific insight is now being used in litigation and policy debates at both the state and federal levels. Our analysis in this Essay shows that, at present, state-level routes are more successful. Further, both state and federal litigation would benefit from strengthening connections between litigants, the scientific community, and the applied forensic behavioral health community of practitioners who conduct forensic evaluations in individual cases. Efforts should be made to further engage in science-informed policy at the state and local levels, to ensure that appellate records reflect the most accurate and applicable neuroscience available, and to connect group averaged scientific evidence with individualized assessments. APPENDIX

This Appendix provides additional methodological detail for the results reported in the main text. The data described below is made publicly available on a Google Sheet database at:

As described in the Essay text, the Database contains information on 494 case opinions in which neuroscience-informed arguments were made to extend Miller v. Alabama to defendants age 18 and older.

The Supreme Court issued its opinion in Miller on June 25, 2012.127 As of this writing, Miller has been cited in over 5,000 cases.128 The main text of the Essay examines the subset of cases citing Miller that have utilized neuroscientific evidence in order to argue that the protections of Miller should be extended to those age 18 and over.129

Here we describe the methods we used to build a new database of these cases.130 We started with the universe of all cases citing to Miller, as of September 26, 2020 (Table A1). This initial search produced 5,384 results. These cases were then narrowed to those that mentioned “neuro!”131 or “brain”, which left 1,019 results (Table A1). For each of these 1,019 cases, we then read the case text carefully to select only the cases that substantially discussed neuroscience, and in which the petitioner was age 18 or older at the time of the crime.132 This produced a final database for analysis of 494 cases (Table A1).

For each of the 494 cases in our database, we examined the age of the party, the use of neuroscientific evidence, and the court’s holding. Notably, more than half (58%) of cases in the database considered pro se petitions; defendants were represented in their attempts to expand Miller in the other 42% of cases.133