Abstract

Masculine honor ideology is characterized by the cultivation, maintenance, and defense of reputations for toughness, bravery, and strength. The link between masculine honor endorsement and increased risk-taking – especially an increased tolerance for and even expectation of violence - is well-established in the literature. However, little empirical research has examined what factors might explain this relationship. This study investigates perceived invulnerability, the cognitive bias that one is immune to threats, as a mediator in the relationship between masculine honor ideology and risky decision-making. Results show moderate support for this relationship’s existence. These findings elaborate on previous research between honor and specific risky decisions by demonstrating honor to instill cognitive biases in its adherents that make them more tolerant of risk, and thus more likely to decide to engage in risky behaviors. The implications of these findings for interpreting previous research, guiding future research, and pursuing specific educational and policy-based efforts are discussed.

A great deal of research has explored the outcomes of honor ideology, a cultural framework that places central value on personal reputation as perceived by others (Brown, 2016; Nisbett & Cohen, 1996). Honor is hypothesized to emerge as a survival strategy in environments defined by resource scarcity and a lack of effective law enforcement (Nowak et al., 2016). In such environments, individuals bolster themselves against the risk of theft or attack by actively cultivating a reputation as someone who should not be “messed with” (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996). Honor endorsing males seek a reputation for strength, toughness, competence, and intolerance of disrespect (Barnes, Brown & Osterman, 2012; Saucier et al., 2016) and both men and women emphasize reputation as central to their personal honor (Barnes et al., 2014; Foster et al., 2021; Rodriguez Mosquera, 2016).

Much research has focused on honor’s link to retaliatory violence in the defense of reputation, demonstrating that honor-endorsers are more likely to respond with violence when they feel their reputation has been threatened in some way (e.g., Barnes, Brown & Osterman, 2012, 2014; Chalman et al., 2021; Cohen & Nisbett, 1994; O’Dea et al., 2019; Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002a; 2002b). However, research has also linked honor endorsement to outcomes beyond retaliatory aggression, including heightened suicide risk (Bock et al., 2019; Crowder & Kemmelmeier, 2017), reticence to seek help for mental health issues (Brown, Imura & Mayeux, 2014; Brown, Imura & Osterman, 2014), issues of gun ownership, gun safety, and gun violence (Bock et al., 2021; Osterman & Brown, 2011), and refusal to vaccinate children against stigmatized diseases (Foster et al., 2021). It should be noted that many of these findings are rooted around the premise that honor endorsers make decisions about various behaviors with a keen awareness of how those decisions will affect their reputation in the eyes of others (for reviews, see Brown 2016; Uskul et al., 2019).

Most relevant to the current research is the finding that honor endorsers are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors. As investigated by Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012), it was found that honor-oriented states within the U.S. demonstrated higher rates of accidental deaths (presumably due to risk-taking behaviors), and that individual-level masculine honor concerns were associated with a willingness to engage in risky behaviors across a variety of behavioral domains. Barnes and colleague Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012) interpreted these results to indicate that honor motivates its adherents to engage in risky behavior to garner and maintain a reputation for toughness, strength, and competence. It has also been observed that honor endorsing men are more likely to seek out dangerous situations that they perceive as being likely to bolster their reputation, and that they perceive such situations as being less dangerous and rate themselves as being more likely to endure prolonged risk in such a situation (Schiffer et al., 2022). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, honor was observed to predict risky health behaviors including not wearing a mask (Kemmelmeier & Jami, 2021), as well as negative attitudes towards risk prevention like social distancing or restrictions on commerce (Schiffer et al., 2021).

It should also be noted that risk is simply an inherent part of honor norms for both men and women. The study of honor culture within an American context originated from studies of southern homicide rates emerging from interpersonal arguments (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996). Later research has clarified that men are expected to retaliate to reputation threats using violence without any thought of the potential risks inherent in any violent confrontation (Uskul et al., 2019, 2023). Furthermore, beyond the obvious risks to physical welfare, honor-based retribution also represents a threat to personal and financial welfare, as it increases the risk of arrest and incarceration (Campbello de Souza et al., 2016).

Similar inherent risks exist for women in cultures of honor. Women’s displays of disloyalty, or even the perception of the same, are interpreted as threats to the honor of a woman’s husband/father, who often “restore” their honor by violence against the woman in question, producing concrete increases in risks of domestic abuse and violence against women within honor states (Brown et al., 2018). However, honor-endorsing women still endorse these norms, despite the potential harm to themselves (Uskul et al., 2023), indicating a tolerance of risk of harm on their part.

It is therefore likely that honor imbues its adherents with certain cognitive biases to facilitate the pursuit of reputation by downplaying the perceived risks of dangerous reputation-enhancing behavior. One such bias might be perceived invulnerability.

Perceived invulnerability

Perceived invulnerability is an optimistic, self-serving cognitive bias that consistently plays a role in risk-taking behaviors across the lifespan (Duggan et al., 2000; Millstein & Halpern-Felsher, 2001, 2002; Potard et al., 2018; Ravert, 2009; Ravert et al., 2009). Those who perceive themselves as invulnerable are less likely to consider the dangers inherent in a situation (Biggs et al., 2014), which predisposes them to violent/aggressive responses (Barry et al., 2009; Chapin, 2001) and other potentially dangerous behaviors, including drinking and driving (Chan et al., 2010; Potard et al., 2018), smoking and drug use (Benet & Kraft, 2019; Milam et al., 2000; Morrell et al., 2016), and risky sexual behavior (Moore & Rosenthal, 1991).

Peer risk-taking behavior and anticipated perception of one’s peers are known antecedents of perceived invulnerability and subsequent risk-taking (Beal et al., 2001; Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Individuals, especially adolescents, look to their peers as behavioral guides and internalize norms, scripts, and values about invulnerability to risk-taking outcomes (Greenwald et al., 2018; Oetting & Beauvais, 1987). Therefore, in a social environment where risky behaviors are tolerated, encouraged, or rewarded with tangible benefits, individuals are more likely to develop perceived invulnerability as a facilitative cognitive bias. We believe this to be the case in cultures of honor.

Honor ideology as an antecedent of invulnerability

As a cultural framework, honor ideology contains norms, values, and behavioral scripts that shape cultural adherents’ decision-making processes (Oyserman, 2017). Certain features of honor are inherently linked to risk, specifically its developing in threatening environments (Nowak et al., 2016), encouraging risky behaviors to violently defend reputation “at all costs” (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996; O’Dea et al., 2019), and prizing reputations for strength, toughness, and competence (Barnes, Brown & Tamborski, 2012). Honor endorsers are thus likely to expect risk as a part of their everyday lives. While it is possible that honor endorsers still fully appreciate, understand, and tolerate this risk, research indicates that individuals who perceive themselves as personally vulnerable to risk are less likely to engage in risky behavior (e.g., Roe-Berning & Straker, 1997), which contrasts with findings that honor endorsers are more likely to engage in risk-taking. It is therefore plausible that honor endorsers understand that risk-taking is often required to garner and maintain their reputations, and thus develop perceptions of invulnerability to facilitate such behaviors.

It follows that the previously identified link between honor and risk-taking across a variety of domains (Barnes, Brown & Tamborski, 2012) would be explained by perceived invulnerability. We specifically predicted a significant indirect effect from masculine honor, through perceived invulnerability, to the risk-taking domains that had previously been linked with masculine honor by Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012). Our measure of perceived invulnerability (Lapsley & Duggan, 2014) contained three subscales: (1) general invulnerability (a general disbelief that one can be physically or psychologically harmed), (2) danger invulnerability (a specific disbelief that one would be personally harmed by engaging in risky behavior), and (3) interpersonal invulnerability (the belief that one cannot be emotionally or psychologically hurt by the opinions of others). We predicted that the general invulnerability and danger invulnerability subscales would both explain the links between honor ideology and the risk-taking subscales. We did not believe that interpersonal invulnerability would play a significant mediating role in these relationships because honor ideology is predicated on the assumption that one can indeed be harmed by the opinions of others, as reputation is not self-contained or self-granted, but depends upon the regard that others hold for you (Brown, 2016; Leung & Cohen, 2011).

Method

Sample and procedure

Participants were 220 college students (n = 89 [40.5%] males, n = 131 [59.5%] females) from a large research institution in the southern United States. Most participants identified as white, non-Latino/a (62.7%), with the remainder of the sample identifying as Asian (10.9%), Latino/Hispanic (9.5%), African American (8.2%), Native American (3.6%), Middle Eastern (1.8%) or “Other” (3.2%). All participants completed an informed consent document prior to participating in the study. Participants then filled out a demographic questionnaire, followed by our honor measure, the covariates, the measure of perceived invulnerability, and the measures of risk-taking.

This study was conducted in accordance with APA ethical standards. All participants passed all attention checks, and thus no participants’ data were excluded from these analyses. Power analysis was conducted to determine the needed sample size for detecting indirect effects with moderate effect sizes, revealing a necessary sample of n = 218—this sample was, therefore, deemed to be sufficient (Schoemann et al., 2017).

Measures

Honor

Previous research on honor ideology and risk-taking has examined honor’s masculine facet. Although the norms of masculine honor apply to males, endorsement of this facet has been shown to impact honor-related attitudes in women as well (Brown, Imura & Mayeux, 2014; Brown, Imura & Osterman, 2014; Chalman et al., 2021). We therefore measured masculine honor ideology using the Honor Ideology for Manhood scale (HIM; Barnes, Brown & Osterman, 2012). The HIM is a 16-item (α = 0.94) Likert-type scale reflecting beliefs about how an “honorable” man should behave. It consists of items regarding reputational concerns (e.g., A real man is seen as tough in the eyes of his peers) and the use of retaliation to honor threats (e.g., A man has the right to act with physical aggression toward another man who calls him an insulting name) that are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree), so that higher scores indicated greater endorsement of masculine honor norms. The final score consisted of the arithmetic average response across all 16 items.

Risk-taking

We utilized the Domain-Specific Risk-Taking Scale (DOSPERT; Weber et al., 2002), utilized by Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012) as our measure of risk-taking. The DOSPERT consists of 40 items representing risky behaviors across a variety of domains. Responses are provided using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely unlikely to 5 = extremely likely). The DOSPERT contains five subscales, one for each specific behavioral domain: ethical behavior (e.g. Not returning a wallet you found that contains $200; α = 0.85), financial behavior (e.g. Investing 5% of your annual income in a very speculative stock; α = 0.85), health/safety behavior (e.g. Riding a motorcycle without a helmet; α = 0.66), recreational behavior (e.g. Bungee jumping off a tall bridge; α = 0.81), and social behavior (e.g. Moving to a city far away from your extended family; α = 0.66). In all subscales, higher scores indicated greater tolerance of/likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors, and the final score for each subscale consisted of that subscale’s arithmetic average.

Perceived invulnerability

We used the Adolescent Invulnerability Scale (AIS; Lapsley & Duggan, 2014; Duggan et al., 2000) to measure perceived invulnerability. Although developed for use in adolescents, this scale has been used in other populations, including college students, the demographic from which we drew our sample (Ravert, 2009). The AIS consists of 21 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), divided into three subscales; general invulnerability, danger invulnerability, and interpersonal invulnerability, each of which have been linked to different risk-taking outcomes (Lapsley & Duggan, 2014). General invulnerability represents a belief in one’s inability to be injured either psychologically or physically, and is assessed by nine items (e.g., I’m unlikely to be injured in an accident; α = 0.85). Danger invulnerability, representing a specific disbelief that one might be physically harmed because of risky behavior, is assessed by six items (e.g., Safety rules do not apply to me; α = 0.79). Interpersonal invulnerability, representing a belief that the personal opinions of others cannot hurt the self, is assessed by six items (e.g., What people say about me has no effect at all; α = 0.81). For all three subscales, higher scores indicated a higher perception of invulnerability, and the final score was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the items.

Covariates

To account for the possibility that other factors play a role in the Honor-Risk-Taking link, we controlled for participant gender (0 = male, 1 = female), as well as the Extraversion and Agreeableness subscales of the 10-item BFI (Rammstedt & John, 2007) and Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). This was done both to remain consistent with prior research on the link between honor and risk-taking (see Barnes, Brown & Tamborski, 2012) and to control for known associations between being male, higher in extraversion and agreeableness, and lower in self-esteem with an increased tendency towards risk-taking behaviors (Byrnes et al., 1999; McElroy et al., 2007; McGhee et al., 2012).

Results

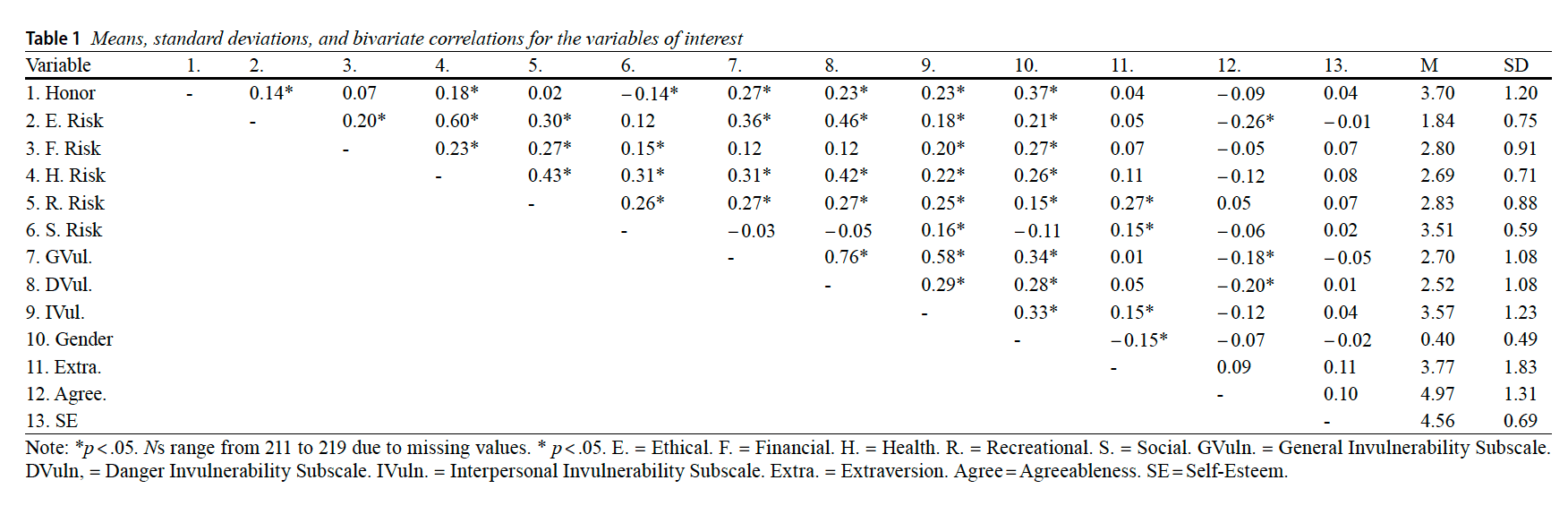

All materials and data are available at the following link: https://osf.io/uzkhp/?view_only=0f16f3265c79483c985d 58715f0a2279. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for the variables of interest can be found in Table 1. The HIM was significantly correlated with higher general invulnerability, danger invulnerability, and interpersonal invulnerability scores (all rs > 0.23, ps < 0.01). The HIM was associated with higher health/safety risk-taking scores (r = .18, p = .01) as well as higher ethical risk-taking scores (r = .14, p = .05). Interestingly, the HIM was associated with lower social risk-taking scores (r = − .14, p = .05) and lower financial risk-taking scores (r = − .16, p = .02).

To determine if vulnerability perceptions mediate the significant associations between honor and the risk-taking outcomes, as well as to determine which vulnerability subscale might be responsible for such an effect, we ran mediation analyses for the Health/Safety and Ethical risk-taking subscales, testing each of the vulnerability subscales separately. Specifically, we assessed if the relationships between the HIM and the two risk subscales would be mediated by the General Invulnerability subscale, the Danger Invulnerability subscale, and the Interpersonal Invulnerability subscale, as demonstrated in three separate mediation analyses for each dependent variable. Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes, 2018) using 5,000 bootstrapped samples to attain estimates of confidence intervals, which are significant at p < .05 if the interval does not contain the integer of 0. Analyses were conducted while controlling for gender, extraversion, agreeableness, and self-esteem.

Health/Safety risk-taking

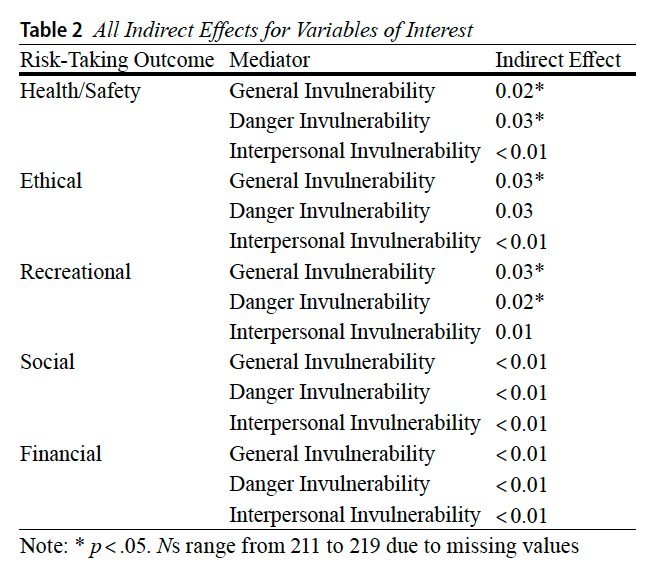

We first assessed the indirect effect of the HIM on the Health/ Safety risk-taking subscale through each of the invulnerability subscales while controlling for gender, extraversion, agreeableness, and self-esteem. Results indicated a significant indirect effect of the HIM on the Health/Safety risk-taking subscale through the General Invulnerability subscale (Mediated Effect—ME = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.003, 0.050], p < .05) and through the Danger Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.002, 0.065], p < .05). No significant indirect effect was found from the HIM to the Health/Safety subscale through the Interpersonal Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.007, SE = 0.007, 95% CI [-0.006, 0.023], p > .05).

Ethical risk-taking

Next, we assessed the indirect effect of the HIM on the Ethical risk-taking subscale through each of the invulnerability subscales while controlling for gender, extraversion, agreeableness, and self-esteem. Results indicated a significant indirect effect from the HIM to the Ethical risk-taking subscale through the General Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.003, 0.064], p < .05), although no significant indirect effect was found from the HIM to the Ethical risk-taking subscale through the Danger Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [-0.002, 0.073], p > .05) nor the Interpersonal Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.007, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.004, 0.023], p < .05).

Additional analyses

Although the HIM had no significant total effect on the Recreational risk-taking subscale, and its effects to the Social and Financial subscale were in the opposite direction, we conducted mediational analyses on these variables for multiple reasons. First, a total effect is not a necessary prerequisite to conduct tests of indirect effects (see Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Thus, it is possible that a significant indirect effect may exist from the HIM to the Recreational subscale despite the total effect being non-significant. Second, an indirect effect may still exist even if the total effect is negative (Davis, 1985; Mackinnon et al., 2000). Therefore, we ran similar analyses for each of the remaining dependent variables and with each of the invulnerability subscales as mediators. While the HIM had no significant indirect effect on Social or Financial risk, (all | MEs | < 0.01, all ps > 0.05), a significant indirect effect existed to the Recreational risk subscale through both the General Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.003, 0.063], p < .05) and the Danger Invulnerability subscale (ME = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.001, 0.054], p < .05). The analogous pathway from the HIM to the Recreational subscale through the Interpersonal Invulnerability subscale was not significant (ME = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [-0.006, 0.035], p > .05). All indirect effects can be found in Table 2.

Discussion

This study sought to further illuminate the link between masculine honor endorsement and risk-taking addressed by Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012) by investigating the role perceived invulnerability as a mediator in this relationship. Results supported this hypothesis, with honor exhibiting significant indirect effects on health/safety, ethical, and recreational risk-taking subscales through perceived invulnerability. However, financial and social risks showed no significant relationship, direct or indirect, with masculine honor.

These results are consistent with research on masculine honor norms, as health and safety risks are likely the most culturally relevant for present-day honor endorsers. Enduring such risks communicates toughness and competence, corresponding to the finding that honor endorsers refuse protective measures that they feel would compromise such a reputation, including protective measures in the areas of interpersonal aggression, mental health, and health prevention (Brown & Osterman, 2014; Brown & Tamborski, 2014; Foster et al., 2021; Kemmelmeier & Jami, 2021). Recreational risks likewise signal toughness and competence (Schiffer et al., 2022). The relationship between honor and ethical risk-taking corresponds to the finding that honor endorsers do not care about “fighting fair” when defending their reputations but are primarily concerned with vengeance itself (O’Dea et al., 2019).

The lack of significant effects for financial and social risks also make sense within the context of honor. Such financial risks may jeopardize an individual’s ability to provide for and protect their family, which runs counter to honor serving as a survival strategy (Nowak et al., 2016), and may therefore not carry a reputation of toughness in the same way that safety or recreational risks do. Social risks also conflict with honor norms, as doing or saying things that make one unpopular could decrease one’s social standing in an honor culture and make them an easier target for insults and abuse (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996).

Our results also indicated a relationship to exist between masculine honor endorsement and interpersonal invulnerability, although the latter did not serve as a significant mediator of any of the risk outcomes we had observed. Nevertheless, this is an interesting finding, and one contrary to our expectations. We had assumed that because honor is predicated on the opinions and judgements of others, rather than being something inherent to one’s view of one’s self (Leung & Cohen, 2011), that honor endorsers would not view themselves as being invulnerable to interpersonal threats. However, we found a modest positive correlation to exist. It is possible that this finding indicates that although honor-oriented men must be vigilant against reputation threats, they must also see their reputation as unassailable, or at the very least see themselves as fully competent of defending that reputation, and therefore feel invulnerable to interpersonal threat. However, it is also possible that honor endorsers are simply reticent to report feeling interpersonal vulnerability, as doing so might be seen as akin to admitting weakness. Future research could benefit from examining potential manifestations of this link between honor and interpersonal invulnerability, especially given recent investigations into honor and social risks, such as relational aggression (e.g., Foster et al., 2022). Future research might also benefit from examining honor-driven perceptions of the social desirability of endorsing risk-taking behaviors.

Overall, our results have specific implications for policy and education efforts that seek to address risk-taking behaviors. Previous research has indicated that one way to dispel illusions of invulnerability, and thereby decrease risky behavior, is to make the risky behavior’s potential consequences salient and relevant (Biggs et al., 2014; Greenwald et al., 2018; Morrell et al., 2016). Research on honor ideology has similarly suggested that with targeted educational interventions, individuals can be made willing to re-evaluate and even change their minds regarding even relatively fundamental aspects of honor ideology (Cihangir, 2013). The creation and implementation of honor-oriented educational interventions should be of primary of importance to educators and policy makers given that the honor-risk relationship has been tied to accidental death rates in cultures of honor (Barnes, Brown & Tamborski, 2012). It might also be beneficial to address the cultural concerns and values that help to create the perceptions of invulnerability that produce risky behavior in the first place, such as by suggesting that failure to seek mental or physical healthcare out of a fear of appearing “weak” might actually have the opposite effect of leaving one weaker and thus unable to defend oneself from attack. Future research should investigate the efficacy of such potential interventions.

Limitations and conclusion

There are a few limitations inherent in this research. First, the sample consisted of young college students from a large, southwestern university. Although this is the same population studied by Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012), exploring these effects in more age-diverse samples may help to understand risk-taking in middle and late adulthood—this would be particularly interesting considering that adherence to cultural norms tends to increase with age whereas risk-taking tends to decrease (Duell et al., 2018; Na et al., 2017). Considering the self-report nature of the DOSPERT, it would be of interest to examine actual behavioral outcomes.

It should also be noted that given the confidence intervals and zero-order correlations, our results can be interpreted as having small effect sizes, indicating that there is still much work to be done in this area, such as experimental approaches or using longitudinal approaches that might allow for the establishment of causality and directionality. However, it is still worth noting that small effect sizes can be meaningful, especially for long-term, cumulative phenomena such as cultural norms and values (Funder & Ozer, 2019). Thus, while these results should be interpreted cautiously, we do still believe them to be meaningful.

Despite these limitations, we feel the current findings do help to help clarify the self-report data of Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012) by explaining the mechanism underlying their effects. We also feel that these data, in combination with the self-report and regional data of Barnes, Brown and Tamborski (2012), helps to clarify the cultural impact of honor on risk-taking.

Overall, we believe that our research represents an important step forward in both the study of honor and the study of risk-taking behaviors. By establishing honor as an antecedent of perceived invulnerability, we have expanded the study of risk-taking by highlighting the importance of considering cultural concerns, values, and beliefs when trying to understand the motives and mechanisms that underlie risk-taking behavior.