Abstract

The underlying mechanisms of drop out in residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment were investigated from the users’ perspective to identify what impacts their drop-out. A survey-based design was used in this study of patients who had decided to drop-out from residential SUD treatment with a therapeutic community approach. The survey included items such as patient satisfaction, psychological burden, and treatment-related factors such as staff competence. We found a high psychological burden among the dropout population. Patients who had considered dropout before leaving treatment reported significantly more difficulty from program-related treatment factors. The patients reported confidence in staff competence. A need for increased access to staff was reported, especially among those actively considering drop-out. Our results suggest that dropping out might not be an impulsive act but a result of prior consideration and decision-making. The study has important clinical implications for social and health services to consider to reduce dropout.

The processes and mechanisms underlying dropout from residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs are complex (Nordheim et al.; Ormbostad et al.). The patient population has a high prevalence of co-occurring health issues in addition to SUD requiring roughly 80% of the resources of the Norwegian specialized treatment system (Hser et al.; Kalseth et al.; Marsden, Gossop, et al.; Pasareanu et al.; Staiger et al.).

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of substance abuse treatment from the patients` perspective (Montgomery et al.), although client perspectives on treatment have been shown to be important for improving health care (Doyle et al.; Urbanoski). Previous studies of dropout from substance abuse treatment and rehabilitation have mostly focused on enduring patient factors, mainly demographics, from the clinicians` perspective, and have focused on completers instead of dropouts (Brorson et al.). The findings from three reviews investigating dropout and risk factors have proven inconclusive (Baekeland & Lundwall; Craig; Stark). The most recent review on SUD treatment even concluded that further research on simple demographic data is of limited value as only cognitive deficits, low treatment alliance, youth and personality disorders were consistent risk factors (Brorson et al.). Ravndal et al. came to the same conclusion concerning specific personality disorders, whereas higher levels of mental distress were associated with increased risk of dropout in more recent studies from residential SUD treatment (Andersson et al.; Stallvik & Clausen.

According to international and Nordic research, the treatment completion rate is about 20–50% (Lopez-Goni et al.; Ravndal et al.; Simpson et al.) and dropout ranges from 17–57% in residential SUD treatment (Andersson et al.; Deane et al.; Samuel et al.). Positive treatment outcomes are one of the most consistent factors associated with treatment completion (Ball et al.; Beynon et al.; Dalsbø et al.; Hser et al.; Meier et al.; Ravndal et al.; Zhang et al.). Positive outcomes from residential treatment include reduced psychiatric symptoms and reduced substance use (Andersson et al.). As there seems to be no significant clinical improvement when dropout occurs before three months, dropout from residential treatment for SUD represents a major barrier for successful outcomes (Eaton; Hawkins et al.; Simpson). A qualitative study from Sweden reported that discharge from medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for persons with heroin addiction often was followed by substance abuse. Some of the discharged persons tried to continue MAT on their own by buying medications illegally, which often were financed by criminal activities. In addition, the living conditions, relation to family and health were negatively affected (Svensson & Andersson). For persons executing a sentence (§12-paragraph for legal statute) at the time of dropout, a consequence is returning to jail. According to Fisher and Neale, patients who enter treatment through the criminal justice system often have reduced opportunities for user involvement. However, it has been reported retention rates for patients that had entered the treatment via the compulsory criminal justice interventions that were similar to those entering SUD treatment voluntary (McSweeney et al.).

Dropping out of treatment has several serious consequences related to both somatic and psychosocial health. Of these, the increased risk of overdose is the most severe (Mathers et al.; Ravndal & Amundsen; Strang). The literature on patients` subjective reasons for leaving treatment is particularly scant and under-investigated with some studies reporting participation rates as low as 5% (Ball et al.; Coulson et al.; Laudet et al.; Nordheim et al.; Palmer et al.; Sayre et al.). Until 2007, service research largely ignored the perspective of patients with SUD (Ali et al.; Carlson & Miller; Tsogia et al.) .Therefore, the need for more knowledge seems crucial to prevent dropout through better understanding and alignment with patients’ needs. Knowledge concerning the processes that precede the decision to leave treatment and the degree to which impulsivity affects dropout is scant and inconclusive. Reviews by Loree et al. and Stevens et al. found that impulsivity is a vulnerability factor for poor treatment outcomes and different conclusions. Ignoring patients’ real needs and morbidity increases the risk of dropout, lack of attendance and poorer treatment in terms of substance use and symptom severity in other life areas (Angarita et al.; Magura et al.; Schulte et al.; Stallvik & Nordahl).

Stress plays a crucial role in drug addiction, and it is an important trigger of relapse (Ruisoto & Contador). Preliminary results from Therapeutic Community (TC) studies have suggested an association between stress and length of stay including associations between higher levels of stress at intake and the likelihood of dropout (Marcus et al.). In an early study, Craig argued that the interaction between patient and content of the treatment had greater impact than patient-related factors alone, and that effective measures to reduce dropout can occur when it is considered a challenge for employees and not merely a problem for patients.

The quality of health-care services may be indicated by patient satisfaction (Trujols et al.. Marsden, Stewart, et al. argued that research on the quality of SUD treatment should focus on satisfaction with staff and program factors. Several studies have linked higher levels of satisfaction to retention in treatment and the association between low treatment satisfaction and increased risk of dropout (Marrero et al.; McKellar et al.; Morris & McKeganey; Schulte et al.; Shipley et al.). The results from a recent study from inpatient treatment suggest that the importance of confidence in staff competence and user involvement are connected to improvement experienced by patients (Andersson et al.). Together, these factors can increase the probability of patient retention by reducing dropout and the severe consequences when it occurs.

The reasons for dropout from treatment are different and previous research is inconclusive. There is a clinical need to investigate why patients drop out so that treatment can be tailored to fit their needs. Adjustments may be necessary when there are internal issues that require intensified psychological/medical services or external issues caused by the program or living environment (Andersson et al.; Harley et al.). Identifying the reasons and mechanisms underlying treatment dropout beyond those in the existing literature could have important clinical implications and pinpoint potential areas to improve clinical services. The present study goes a step beyond previous research by trying to capture thoughts and emotions in advance of dropping out to understand and identify any process prior to the event. The aim of this study was to investigate; (1) how patients perceived treatment before dropout at a modified residential TC program and (2) which factors may have contributed to the decision to leave treatment. Finally, we examined (3) differences between noncompleters with and without thoughts of dropout and whether dropout seems to be a deliberate or impulsive act.

Materials and methods

Design and study settings

The study was conducted at the point of dropout at a publicly funded residential institution for multidisciplinary specialized SUD treatment in the middle region of Norway. Residential treatment in Norway can include both hospital-based inpatient services and specialized drug and addiction treatments in residences outside hospital settings were patients live and get treated at the same time. Residential treatment programs can be therapeutic communities, but also other programs were people stay and receive treatment at the location. The survey was conducted over a five-year period (2012–2017) and approved by Norwegian Social Science Data Services. The residential treatment facility has a systemic approach, providing a six to nine-month modified TC program for SUD (Evans & Kearney). The program is structured and organized in stages, and treatment is largely group-based with mandatory and voluntary groups in addition to individual therapy (Dye et al.). Environmental therapy consists of a highly structured daily regime organized according to a routine and program activities emphasizing personal responsibility and self-help using peer models. Patients are exposed to different roles and relationships that they themselves can take during the treatment program. Through three treatment stages they are receiving increases in levels of responsibility and thus have roles with more responsibility at the later stages than in the beginning (De Leon). Staff are made up of social workers, nurses, and psychiatrists, and both individual and group sessions are used. Individual adjustments to treatment are made according to patients’ needs and are based on psychological assessment/evaluation and environmental observations in consultation with the patient. The modifications of the program are due to increased knowledge on co-occurring disorders among patients with SUD (Sacks et al.), as well as claims from the Norwegian Patient Rights Act and the Special Health Services Act, where the patient is granted rights to individually tailored treatment (Skotland). The modified TC treatment model are more flexible, less intensive and the treatment is more individually tailored (Sacks et al.). In addition, the institution has implemented family therapy based on a systemic approach (Jones). Treatment in Norway is free of charge and there is a high trust from users of our health care services in general, but also in the SUD treatment section. Patients are treated when needed, and with the respect and dignity they need and deserve.

Definition of dropout

Definitions of dropout vary. Thus the lack of a unified definition of dropout in the literature represents a challenge for the comparison of results (Brorson et al.; Evans et al.). In the present study, the term ‘dropout from treatment’ was widely defined as noncompletion of a planned residential program. Transferring patients to other treatment facilities may be an attempt to avoid dropout. We also included the patients who were discharged before treatment completion. Previous studies comparing discharged and not discharged found no demographic nor clinical differences, and these groups have therefore been merged in other studies of dropout (Andersson et al.; Lejuez et al.).

Patients enrolled in this study had decided to leave treatment; and were discharged or transferred to other institutions. It should be noted that some patients regretted leaving and returned to the institution within days, but they were still defined as ‘dropouts’ and their thoughts were included. Dropout was defined as an impulsive act when the person who left treatment did not report any dropout thoughts during the treatment stay. About 20% of the dropout population received treatment according to §12. The § 12 law provides the opportunity that criminal proceedings may in some cases take place in approved treatment facilities for SUD. Transfer and administrative discharges were included as dropouts since they dropped out of the original placement and were transferred or discharge because of the dropout and not other circumstances.

Participants and procedures

Participants were patients with an illicit SUD defined by the diagnostic instrument International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) World Health Organization [WHO], who had undergone detoxification before entering residential treatment. During the five-year study period (2012–2017), 98 out of 234 (42%) patients left treatment and 68 (69%) of these responded positively to participation. One patient was transferred to a psychiatric ward and one is deceased. A total of five (8%) patients were unilaterally discharged and six (9%) were transferred to another institution. Data were collected using a questionnaire designed for this study. At the point of dropout, patients were informed of the study as part of the dropout procedure at the clinic and requested to complete the questionnaire and consent to participate. The questionnaire was distributed in an envelope bearing the researcher’s name and delivered to a mailbox (researcher access only) to reduce the possibility of responses being affected by or in conflict with their relationship to staff. Those who for various reasons had not received the questionnaire or had no opportunity to respond were contacted by the principal investigator and requested to respond to the questionnaire by telephone. Reasons for noncompletion of the questionnaire were that patients did not want to participate, or could not be reached. The study was reviewed and approved by Norwegian Social Science Data Services for research.

Measures

In addition to discussions with professionals and researchers in the field, the process of developing the questionnaire started in April 2012 with the collection of information on patients` experiences through two group interviews. This method was inspired by focus group techniques without fulfilling the formal requirements (Malterud). It is useful at an early stage for developing questionnaires in quantitative research and for clarifying research questions (Johannessen et al.). The first group consisted of five patients, and the session was conducted at in an early phase of treatment. Two of these patients had a previous history of treatment dropout. The second group consisted of only two patients in their last phase of treatment. Both groups were asked the following question:

‘What questions should we ask patients who are considering dropping out of treatment? What is important to know about patients before they decide to leave?’ The 24-item questionnaire was partly based on items from a standardized questionnaire for assessing treatment satisfaction developed by the Norwegian Knowledge Center for the Health Services (Dahle & Hestad Iversen). An abbreviated version of the questionnaire (ten items) was included in the present study. The following variables were included (1) Demographic characteristics (age, gender, housing, major source of income, employment status and previous treatment); (2) Self-reported psychological burden at the time of dropout (presence/absence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, trauma, internal turmoil and other); (3) Patients` subjective reasons for leaving treatment (program(PRF)and nonprogram-related reasons(NPRF)). (4) Questions concerning the mechanisms underlying dropout (did you have thoughts of dropout and for how long, and when did they start?); (5) Program expectations and experiences (questions about treatment factors the patients had perceived to be difficult, treatment satisfaction, reception at the institution, waiting time, feeling secure, being met with respect and courtesy and if they had received enough information before intake); (6) Relations with clinical staff and other patients in treatment (staff competence, enough time for conversations, and importance of fellow patients). Variables were measured on a five-point rating scale ranging from ‘1’ (not at all”) to ‘5’ (to a considerable degree).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample demographics, self-reported psychological characteristics, patients’ subjective reasons for dropout and treatment satisfaction scores. To investigate whether dropout seems to be a deliberate or impulsive act, Mann-Whitney U tests were used to examine differences in mean of scores between patients that had and had not considered dropout for up to two months before leaving treatment. The following variables were included: patient satisfaction, self-reported psychological burden and sum of treatment-related factors rated difficult by the patient. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 22;IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographics and clinical variables

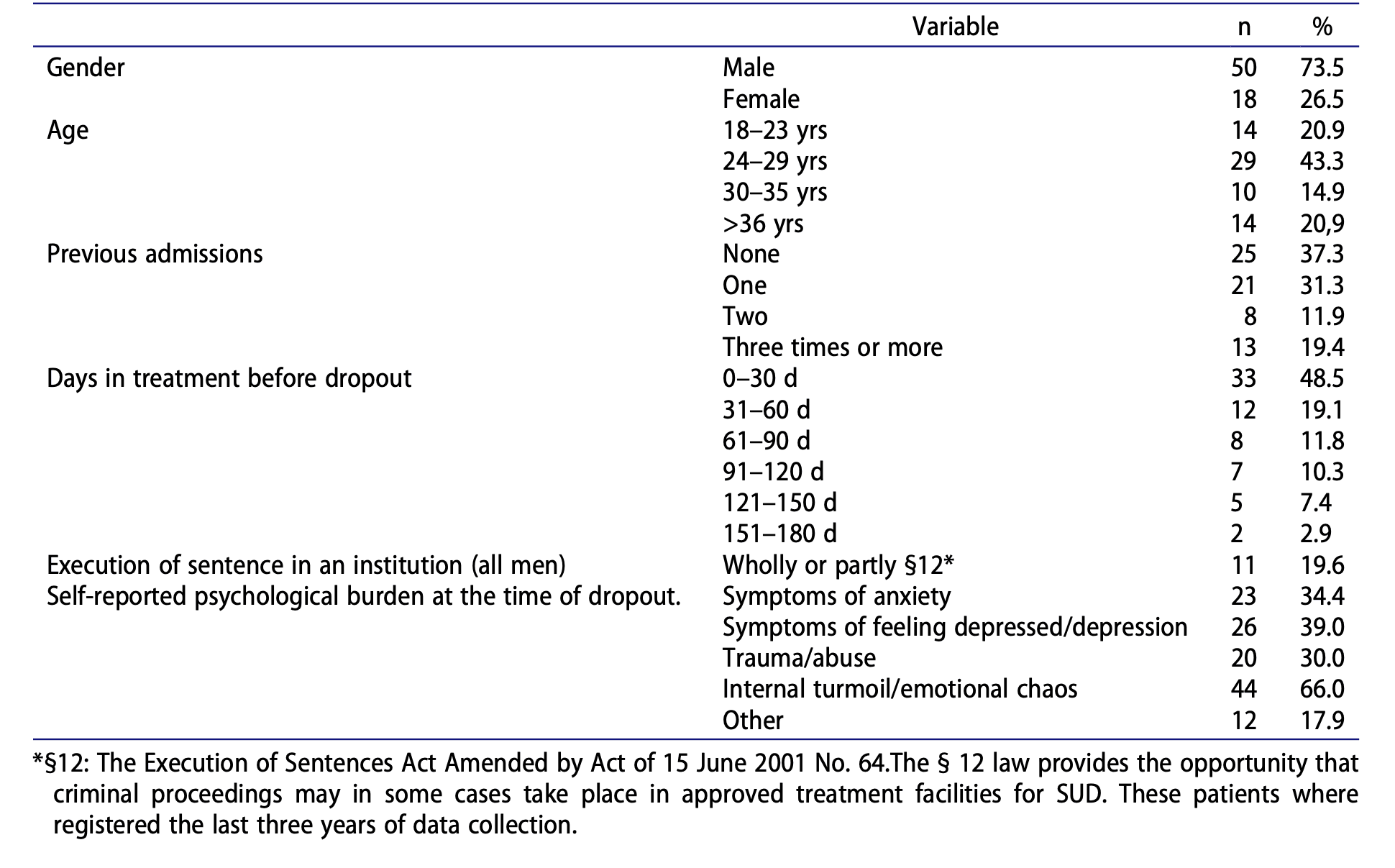

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 68 participants were included in the study, 50 (74%) of whom were men and 18 (27%) women which provides an adequate picture of the population at the institution. Ages ranged from 18 years old to the mid-50s. Mean treatment time before dropout was 47.9 days (standard deviation 44.695 days), ranging from 1 to 157 days. Dropout occurred before 30 days (defined as ‘early dropouts’) for about half of the participants (33), 17 patients dropped out of treatment within the first week.

Self-reported psychological variables

At the time of dropout, about one third of the patients reported symptoms of anxiety, 40% felt depressed and 66% reported emotional chaos. At the time of dropout, a total of 30% reported that they had experienced trauma/abuse in their lifetime.

Reasons for dropout

Patients’ subjective reasons for leaving treatment were categorized into PRF and NPRF. PRFs was reported by 23 (35%) and NPRFs by 33 (51%) as reasons for leaving, while 23% reported both PRF and NPRF as reasons. About 60% reported one reason for dropout, whereas 40% reported multiple reasons (two or more). Patients who were discharged (5) or transferred to another institution (6) comprised 17% of the total. Unspecified reasons for dropping out in the ‘other’ category were cited by 14 (22%). There is no certainty around what these other cases involve.

Nonprogram-related factors

Half of the participants reported external influences as reasons for leaving treatment. Of these, 14 (21.6%) referred to significant others (e.g.; partner, network, children), three (4.6%) related their decision to the economy and four (6.2%) referred to school/work.

Program-related factors

In terms of PRFs, the TC work structure was reported to be difficult and challenging by 29 (43%) patients. Group therapy was reported challenging and difficult by 19 (28%). Having to share accommodation with others was reported to be difficult by 10 (15%) patients. Not having access to clinical staff when needed was reported as challenging by 26 (39%) patients.

Treatment satisfaction

Ten items assessing levels of satisfaction with different aspects of the residential treatment were selected for the present study. In terms of expectations 15 (24%) found the waiting time for admission to be long/very long and nearly 35 (57%) reported receiving insufficient information about the institution before admission. A satisfactory reception to the institution was reported by 64 (94%) (high/very high response category) and 61 (89%) experienced respectful and courteous treatment. None of the patients experienced patronizing or offensive treatment by the clinical staff. However, seven (11%) did not feel safe at the institution (not at all or satisfied to some degree). In terms of potential benefit from treatment (high/very high response category), 49 (71%) reported a belief that they would have benefitted from it if they had continued treatment.

Relations with staff and fellow patients

A total of 49 (72%) reported medium/high/very high confidence in staff competence although 26 (43%) felt they had not received enough time for conversations and contact with clinical staff. The importance of fellow patients varied, 53 (77%) rating them as high/very high in importance, and 15 (23%) rating their importance as low/very low.

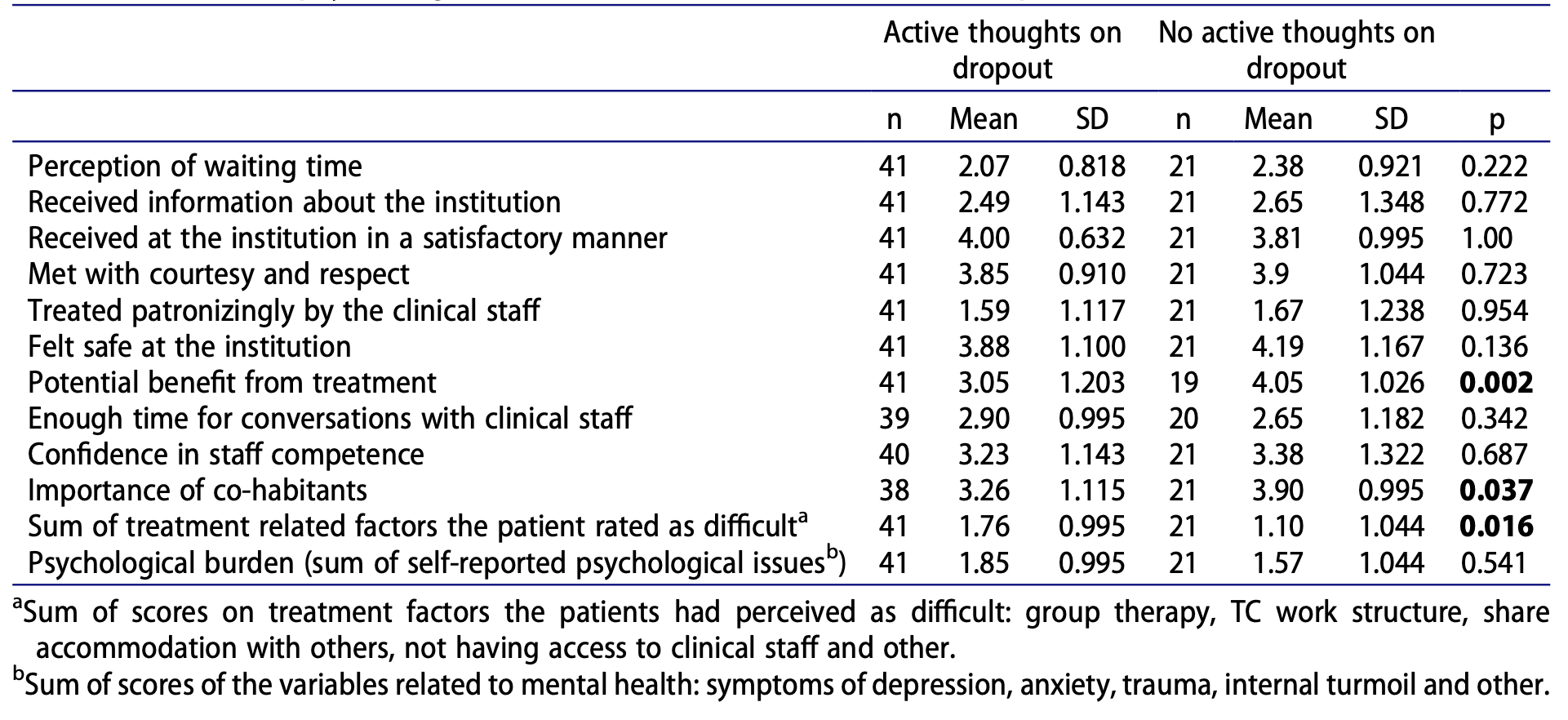

Impulsive versus deliberate dropouts

One of the main findings was that a majority, 41 (66%) had actively considered leaving treatment for up to two months before dropout and 27 (69%) of these had considered leaving from the day they arrived at the clinic. The remaining twelve (31%) had considered leaving one to two months before they dropped out.Differences in mean scores (patient satisfaction, psychological burden and sum of treatment-related factors rated difficult) between those actively considered leaving and those that had not considered leaving for up to two months before leaving treatment are shown in Table 2.

In this sample of 68 patients in residential SUD treatment who dropped out over a five-year period, 33 (49%) dropped out within the first month (defined as early dropouts). Half of these dropped out within the first week. In terms of self-reported psychological issues, 44 (66%) reported internal turmoil/chaos and more than two psychological issues, showing high psychological burdens in the sample. Those who dropped out after 30 days, reported significantly greater psychological burdens (p = .036) than early dropouts.A significant majority of dropouts reported having active thoughts of dropout before leaving treatment i.e., 27 (69%) had them from day one, although they believed they may have benefited from staying. They also reported more difficult PRFs and that fellow residents were of less importance to them. The significant differences between those who actively considered dropout versus those who did not were found in the variables ‘potential benefits from treatment’ (p = .002), ‘importance of fellow residents’ (p = .037) and ‘sum of treatment factors rated as difficult by the patient’ (p = .016).

Discussion

Program and nonprogram related factors in leaving treatment

About half of the 68 participants in the study dropped out before 30 days had passed, with 69% who considered leaving treatment from the first day despite a large number reporting they could have benefitted from staying. PRFs were reported by 35% and 51% reported NPRFs as reasons for leaving treatment, while 0% reported two or more reasons. The ‘other’ category of reasons for dropping out were reported by 22%.

Most of the sample (75%) reported confidence in staff competence and a presumption of potential treatment benefit (high/very high response category) if they had remained in treatment. However, whether emotional distress exceeding levels of tolerance affected their ability to adapt and behave according to the institution demands and their own feelings was not confirmed. Associations between high levels of psychological distress during the first month in treatment and lower adherence to the program have been found in previous TC studies, suggesting that their mental state may prevent patients from fully participating in the TC (Goethals et al.). Emotion regulation may be understood as the ability to adapt and respond adequately with flexibility and tolerance when experiencing negative emotions (Gratz & Tull). Patients’ ability to understand and interpret high levels of negative emotions and persist in goal-directed behavior has been reported as an important indicator of treatment persistence (Hopwood et al.). Given the heavy psychological burden among dropouts in the present study, it should be discussed whether lower distress tolerance, mainly referred to as ‘the perceived capacity to withstand negative and emotional and/or other aversive states’ (e.g., physical discomfort) could be an issue. Daughters et al. found psychological but not physical distress to predict dropout from a residential facility for SUD treatment. Unlike completers, anxiety sensitivity and significant higher levels of cortisol were found to be a predictor of dropout (Daughters et al.). Targeting emotional distress at an early stage of treatment and helping patients develop other coping strategies than substance use may reduce early dropout.

Therapeutic community work structure

Our results revealed that more than 40% found the structure of the TC program to be problematic. Although TCs vary in content and form, treatment experiences in TCs has previously been described as restrictive and stressful, requiring extensive coping strategies for recovery (Marcus). Patients in our sample with high psychological burdens may find the treatment more stressful and may not possess extensive coping strategies, and therefore dropout. Not knowing the principles of the treatment program and its expectations can cause stress if patients are not prepared. Preparing patients before intake and reassuring them from the beginning may reduce stress. Again, the lack of information (57%) and unmet needs for conversations (43%) could be seen in this context and may lead to patients perceiving the TC work structure to be difficult.

Other studies of the perceived hospital ward atmosphere in TC facilities have underlined the importance of orderliness of the therapeutic environment with regards to treatment completion (Carr & Ball). McKellar et al. found that vulnerable patients at high risk of dropout seemed to profit in an environment characterized by a high degree of support but low control.

In residential treatment, support from significant and important others may not always be available, and support from clinical staff is even more important. In the present study, 43% of the dropout population reported receiving insufficient time for conversations with clinical staff. Together, these findings represent a challenge concerning the need for monitoring, easier access to clinical staff and individual adaptation to the TC environment. Insufficient information could also be a contributing factor to the reported problems of the TC work structure.

Group therapy

About 28% of patients reported that group therapy was difficult. Participating in group therapy can increase anxiety. Patients with social anxiety disorders may have difficulty in tolerating group-based treatments and require individual treatment sessions beforehand (Book et al.; Hartwell et al.). Sharing ingroup sessions and pressure to follow the structure of the group may increase the severity of patients` symptoms. Instead of engagement and active participation, which can promote adherence to the program, dropout thoughts may be induced. Previous studies of TCs have shown an association between high levels of psychological distress in the first month and reduced adherence to the TC environment (Goethals et al.). Interventions targeting anxiety, depression, worry and distress tolerance, may gradually prepare patients to participate in ordinary groups. Previous studies support this and have shown such interventions to be effective among these patients; some result in significantly greater improvement (Bornovalova et al.; Marcus et al.; Norr et al.).

Treatment satisfaction

Patients` autonomy and influence on treatment services are crucial in treatment for SUD (Brener et al.; McCallum et al.; Ormbostad et al.; Rance & Treloar). Previous studies have found satisfaction to be significantly associated with completion of treatment (Marrero et al.; McKellar et al.). Patients who reported lower levels of treatment satisfaction were 2.5 times more likely to dropout (Marrero et al.). A positive association was seen between greater levels of service intensity, satisfaction, completion and retention, especially for patients in residential treatment (Hser et al.). Most patients in the current study (95%) felt that they had been received in a satisfactory manner. However, the high percentage of patients who found important components of the treatment difficult, is an important issue that can be resolved by adjusting the program structure and customizing the treatment further to fit their needs. A large number of patients report confidence in staff competence and believed that they could have been helped if they had remained in treatment. Thylstrup underlined the necessity of a contextual understanding of the program components and found that better patient experiences of staff availability were strongly correlated with all aspects of treatment satisfaction.

Relations with clinical staff and other patients

It is well established that the quality of the working alliance between patient and therapist is of great importance with regards to retention and outcome of treatment; and that lower-quality alliances are associated with higher dropout rates (Brorson et al.; Kothari et al.; Meier et al.). Although we know that frequency is a major factor, we know too little of what defines the quality of this relationship (Meier et al.). A core component seems to be the therapeutic bond between emotional connection, support and understanding (Healey et al.). A study on the role of therapeutic alliances in SUD treatment showed greater reduction in distress among participants who developed a stronger alliance during treatment (Urbanoski et al.). Nearly 70% of those in our study reported confidence in staff competence. However, only 28% reported ‘high/very high satisfaction’ on items concerning sufficient time with clinical staff and felt that staff members were not available when needed. The lack of time spent with therapist might then raise the question whether it was possible to develop an adequate treatment alliance prior to the decision of leaving treatment. In a recent study of therapeutic relationships in a TC, the results indicated that the emotional aspect of therapeutic alliances are an important predictor of dropout (Janeiro et al.). This coincides with results from a study of patient satisfaction and outcomes amongst completers where staff confidence was found to be the most significant domain of treatment satisfaction correlated with outcome (Andersson et al.). Nordheim et al. found that lack of personal contact with staff was one of the four issues that patients cited as reasons for dropping out of treatment.

In the present study, it may be suggested that the relationships and working alliance are perceived as adequate, but that the frequency of time spent with clinical staff was insufficient with regards to their psychological burden and needs. This is consistent with the 75% of the respondents who reported being troubled by psychological problems and who said that counseling was important in a more recent study, i.e. significantly more men than women reported insufficient psychiatric services to meet their needs (Stallvik & Clausen). For patients in a state of emotional distress, the experience of not receiving enough help, may induce or amplify thoughts or feelings about leaving treatment. In a recent TC study, retention amongst vulnerable patients was found to be affected by intensive care and support together with time and space (Tompkins et al.).

Is dropout a deliberate or impulsive act?

Most of the dropout population reported deliberately leaving treatment. This finding seems to be in line with the results of Bankston et al., who reported that the level of impulsivity upon admission was not associated with treatment retention among residents in a TC. One of our main findings was that a large majority of the dropout population (66%) had considered leaving treatment, and they reported that treatment-related factors are difficult (groups, work structure). A case study by Ormbostad et al. found that the dropouts had thoughts of dropout and a decision-making process prior to the dropout. By monitoring and supporting high-risk patients, early attrition could be reduced (Harley et al.). In the present study, patients who had considered dropout before leaving treatment, reported other patients to be less important than those without such thoughts. This finding is supported by a qualitative study by Nordfjærn et al. in which failure to establish positive social relations was reported as a core reason for premature dropout and that social relationships with therapists and fellow patients was important with regard to treatment experiences, which increased motivation. Patients also reported they were convinced to stay in treatment by their fellow patients. These influences and support could be essential in a TC setting where the methodology is based on a high degree of involvement with other patients and their treatment. In any case, attention should be paid to this obstacle during treatment to target those who are most likely to drop out and give special attention to them.

Strengths and limitations

Although we believe the present study has important clinical implications, it has limitations. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. The sample size is small (n = 68) and based on a predominantly male population in a TC. However, it reflects the actual ratio of men to women in this population. Moreover, in the present study dropout is widely defined and we do not know how many of those left treatment, returned or completed it. The main reason for this was to focus on patients` thoughts when they leave or do not follow their planned program. Finally, the study gives us no information about completers and their dropout thoughts, which might be present but resolved because they remained in treatment. One of the study’s strengths is that the data were collected at the time of actual dropout, making it possible to capture the patients’ current emotional state. The response rate was relatively high because approximately 60% of the dropout population at the institution responded. To our knowledge, this is high compared with other dropout studies (Ball et al.).

Implications

Results from this study suggest that the processes before dropout occurs are deliberate and that interventions can be tailored to meet the patients’ needs. Providing enough information about the treatment program and its elements before they come might reduce early dropout, also securing them the first month and reassuring them that these dropout thoughts are normal and quite common and that they should express them instead of trying to hide that they are having them. For those dropping out later because of high psychological burdens, these can be met by giving their psychological issues attention as well as addressing their SUD issues simultaneously to reduce dropout.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings seem to suggest a complex interaction between the individual and the environment that causes dropout, even though patients may seem to have confidence in the clinical staff and the treatment program. Explaining and understanding patients’ perceptions of the term ‘intern turmoil and chaos’ is challenging. Becoming sober and having to face the consequences of maladaptive behavior caused by years of addiction may be overwhelming. Together with treatment demands, this may exceed the ability to remain in treatment and increase retention. In a process of considering whether to continue or leave treatment, support from fellow patients or therapists might be crucial. It is well known that relationships with significant others are of great importance. However, in residential treatment, the absence of significant others may to some extent be compensated for by the therapists and fellow patients. In addition, high psychological burdens and cognitive deficits may also affect the decision-making process. The importance of meeting patients’ needs for conversations in this process should not be underestimated as this could have serious consequences for affected individuals. The results also imply that the decision to dropout is mostly not based on impulsive reactions, but direct reasons of internal and treatment-related factors that we as service providers can influence to reduce future dropout and improve treatment outcomes.