Abstract

Objective: To examine: (1) if youth who have mental health disorders receive needed services after they leave detention—and as they age; and (2)inequities in service use, focusing on demographic characteristics and type of disorder. Method: We used data from the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a longitudinal study of 1,829 youth randomly sampled from detention in Chicago,Illinois in 1995. Participants were re-interviewed up to 13 times through 2015. Interviewers assessed disorders using structured diagnostic interviews and assessed service use using the Child and Adolescent Service Assessment and the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents. Results: Less than 20% of youth who needed services received them, up to median age 32 years. Female participants with any disorder had nearly twice the odds of receiving services compared with male participants (OR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.41, 2.35). Compared with Black participants with any disorder, non-Hispanic White and Hispanic participants had 2.14 (95% CI: 1.57, 2.90) and 1.50 (95% CI: 1.04, 2.15) times the odds of receiving services. People with a disorder were more likely to receive services during childhood (< age 18) than during adulthood (OR: 2.29; 95% CI: 1.32, 3.95). Disorder mattered: participants with an internalizing disorder had 2.26 times and 2.43 times the odds of receiving services compared with those with a substance use disorder (respectively, 95% CI: 1.26, 4.04; 95% CI: 1.49, 3.97). Conclusion: Few youth who need services receive them as they age; inequities persist over time. We must implement evidence-based strategies to reduce barriers to services.

Mental health disorders are common and enduring among youth in the justice system. More than 60% have a mental health disorder.1 Substance use and disruptive behavior disorders are the most prevalent, affecting approximately one-half and one-third of youth, respectively.1 More than one-half of youth with a mental health disorder have more than one.2,3

Access to mental health care in correctional settings is a legal right in the United States—a constitutional standard established by Estelle vs Gamble4 in 1976 and protected by federal laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act.5,6 Mental health services can improve youths’ health and behavioral outcomes. Yet, many youth in the juvenile justice system do not receive needed services. Persons of color, male youth, and older youth who have a disorder are less likely to receive mental health services than non-Hispanic White and female youth, and those who are younger.7-19 Moreover, diagnosis matters: youth with substance use disorders are less likely to receive services than those with mood, anxiety, and personality disorders.16

Many youth continue to need mental health services as they age. Among youth who had a disorder at detention (median age, 15 years), almost one-third of female and more than one-half of male participants still had a disorder 15 years later.20 Untreated disorders have consequences: low educational achievement,21-23 difficulty obtaining and maintaining employment,23-25 recidivism,26,27 drug overdose,28 and death.28-30 We investigate a critical question: do the inequities in mental health service use experienced by youth in the juvenile justice system persist as they age?

To assess the literature, we searched for longitudinal studies of youth in the juvenile justice system, published in a peer-reviewed journal since 2000, that examined mental health service use. We found only 5 studies (literature table available upon request),7,18,31-33 which found that between 14% and 51% of participants received mental health services; findings varied by the length of the follow-up (eg, 60 days7 vs 24 months18,32). Findings are also inconsistent because studies used different samples: first-time offenders,31 “serious” adolescent offenders,18,32 and youth in corrections being released into the community.7,33

Although they are informative, prior studies have limitations. The longest follow-up was only 2 years,31,32 up to a mean age of 18 years, thus providing no information about transitions to adult mental health services. Moreover, studies had 1 or more of the following methodological limitations: (1) assessed the prevalence of service use overall,31,32 rather than examining whether youth who needed services received them; (2) did not examine sex differences in service use18,31,33 even though diagnostic profiles vary by sex,1,20 and female individuals with disorders are more likely to be referred to services than male individuals;10 and (3) did not investigate racial and ethnic inequities in service use,31,33 a critical omission because Black and Hispanic youth are disproportionately arrested and incarcerated.34 Data are needed to increase engagement in treatment, to ameliorate disparities, and to improve long-term outcomes.

This article addresses these omissions. We use data from the Northwestern Juvenile Project, the only large-scale prospective, longitudinal study of mental health needs and outcomes of youth in the justice system. Analyzing data on mental health service use up to 16 years after detention, we examine: (1) whether youth who need services receive them after they leave juvenile detention, up to a median age of 32 years; and (2) inequities in service use as youth age, focusing on differences by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and type of disorder. We hypothesized that: (1) few youth who need services will receive them as they age; (2) male participants and persons of color will have lower odds of receiving services compared with female and non-Hispanic White participants; (3) participants will have lower odds of receiving services when they are adults compared with when they are children; and (4) youth with internalizing disorders (mood and anxiety disorders) will have higher odds of receiving services than those with substance use or disruptive behavior disorders.

METHOD

The most relevant information is summarized below. Additional details are provided in Supplement 1 (available online) and published elsewhere.35-37

Sample and Procedures

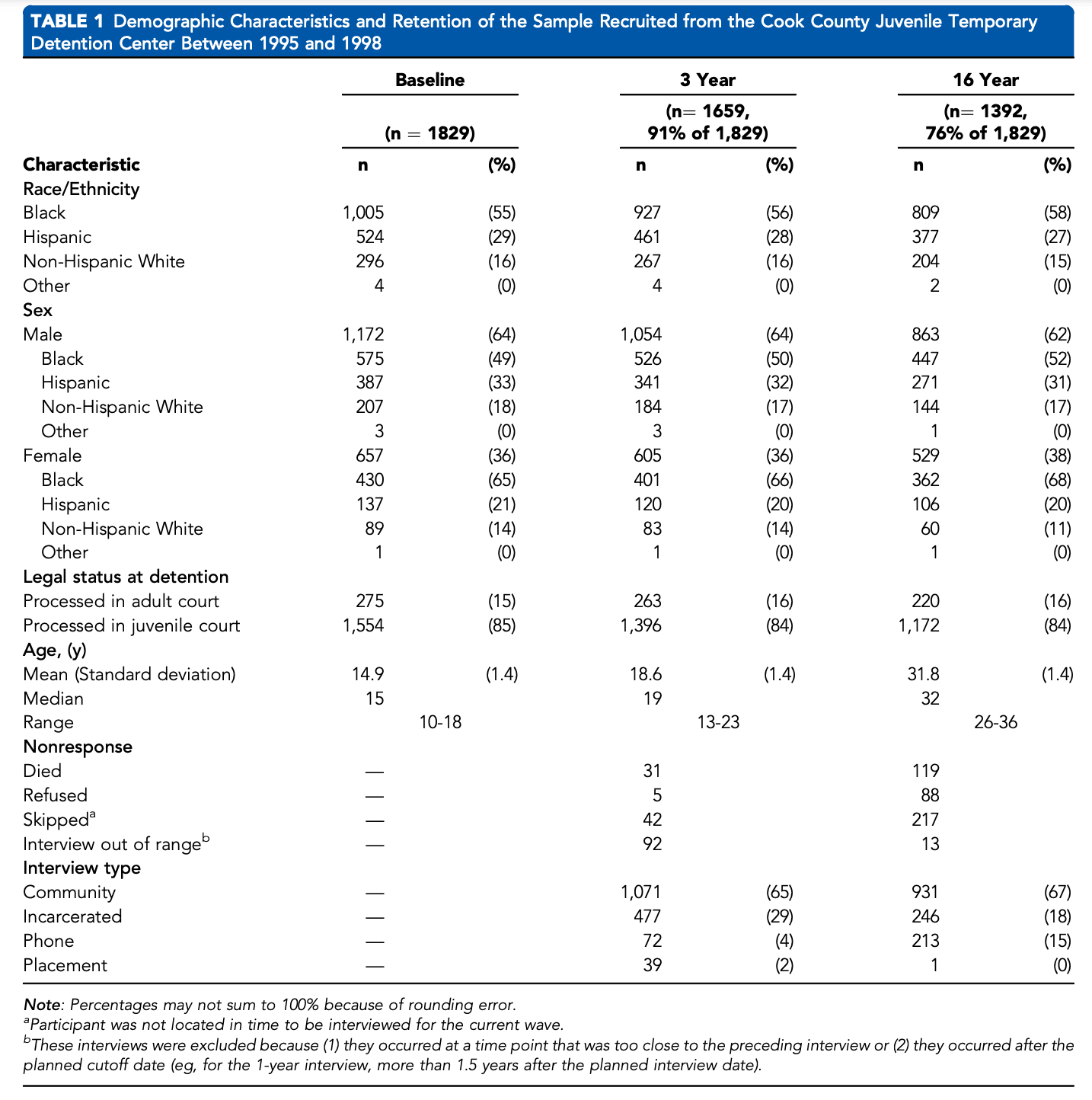

We recruited and interviewed a stratified random sample of 1,829 youth at intake to the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (CCJTDC) in Chicago, Illinois, between November 20, 1995, and June 14, 1998. The CCJTDC is used for pre-trial detention and youth sentenced for fewer than 30 days. To ensure representation of key subgroups, we stratified the random sample by sex, race/ethnicity (Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, other), age (10-13 or 14-18 years), and legal status (juvenile or adult court). The sample included 1,172 male and 657 female participants; 1,005 were Black (55%), 524 were Hispanic (29%), 296 were non-Hispanic White (16%), and 4 identified as other race/ethnicity (0%) (Table 1). The median age was 15 years (mean [SD], 14.9 [1.4] years).

Face-to-face structured interviews were conducted at the detention center (most within 2 days of intake). All participants were re-interviewed at approximately 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 14, 15, and 16 years after the baseline interviews. Participants were re-interviewed whether they lived in the community or in correctional facilities. A random subsample (n ¼ 997) received additional interviews at 3.5 years and 4 years. The last 800 participants enrolled at baseline received additional interviews at 10, 11, and 13 years after baseline.

Participants signed either an assent (<18 years old) or consent (18 years old) form. The institutional review boards of Northwestern University, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Cook County Health Services, and the Illinois Department of Corrections approved study procedures and waived parental consent for persons younger than 18 years, consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk.38 This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies as applicable (see Supplement 2, available online).

Measures

Race/Ethnicity. Race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, nonHispanic White, other) was self-identified at the baseline interview. All participants who identified as Hispanic were classified as Hispanic regardless of race.

Need for Mental Health Services. We classified participants as needing mental health services if they met criteria for one or more mental health disorders at the time of the interview.

Beginning with the first follow-up interview, we administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children39,40 (DISC-IV; Child and Young Adult versions), based on the DSM-IV, to assess the past-year prevalence for internalizing disorders (mania, major depression, hypomania, dysthymia, generalized anxiety, panic, and posttraumatic stress), disruptive behavior disorders (conduct, <18 years and oppositional defiant, <18 years), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (<18 years). Beginning with the 6-year follow-up, we administered the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI),41,42 based on DSM-IV, to assess mood and anxiety disorders (past-year). We previously conducted sensitivity analyses to determine that changes in prevalence over time were not due to changes in measurement (Supplement 1, available online).37,43

To assess for past-year antisocial personality disorder (categorized as a disruptive behavior disorder) and substance use disorders at all follow-up interviews, we administered the Diagnostic Interview ScheduleIV (DIS-IV).44,45 The DIS-IV assesses the following substance use disorders: alcohol, opioid, marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens/PCP, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, and unspecified drugs. As with prior work, we scored participants who met criteria for substance use disorder with “partial recovery” as having the disorder.43

Mental Health Service Use. For all follow-up interviews, we administered the Child and Adolescent Service Assessment (CASA, modified) and the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA, modified) to collect detailed information about service use.46-49 Questions assessed mental health service use and the type of services received in schools and inpatient and outpatient settings in community or correctional settings in the past 3 months.

Statistical Analyses

We used commercial software (Stata 15; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all analyses50 and StatTag to connect Stata output to manuscript text.51 To generate prevalence estimates and inferential statistics that reflect CCJTDC’s population, participants were assigned sampling weights, augmented with nonresponse adjustments to account for missing data.52 We estimated standard errors using a Taylor series linearization.53,54

Prevalence of Service Use. We summarize prevalence of service use at 8 time points: follow-up interviews corresponding to approximately 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 14, 15, and 16 years after detention.

Changes in Service Use Over Time. We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs)55 to fit marginal models to examine: (1) differences in prevalence of service use among those with disorders by age, sex, and race/ ethnicity; and (2) changes in prevalence of service use by type of disorder as youth aged. Service use was modeled as binomial with a logit link function. Models used all available interviews, an average of 7 interviews per person (range, 1-13 interviews per person). We used all available data from interviews starting with the first follow-up time point.

Models included covariates for sex, race/ethnicity, aging (time since baseline), age (<18 years; 18 years), age at baseline, incarceration during the past 3 months, and legal status at detention. We included age as a covariate because mental health service use may vary as participants move from pediatric to adult service systems. We included an interaction term for sex and disorder because, in both the general population and criminal justice facilities, persons who are female are more likely to receive mental health services compared with those who are male.56-58 Because incarceration may alter service use, all models included an indicator variable of whether participants were incarcerated during the recall time frame for service use. Analyses exclude the 4 participants who identified as “other” race/ethnicity.

RESULTS

Service Use as Youth Age: Participants With Any Disorder

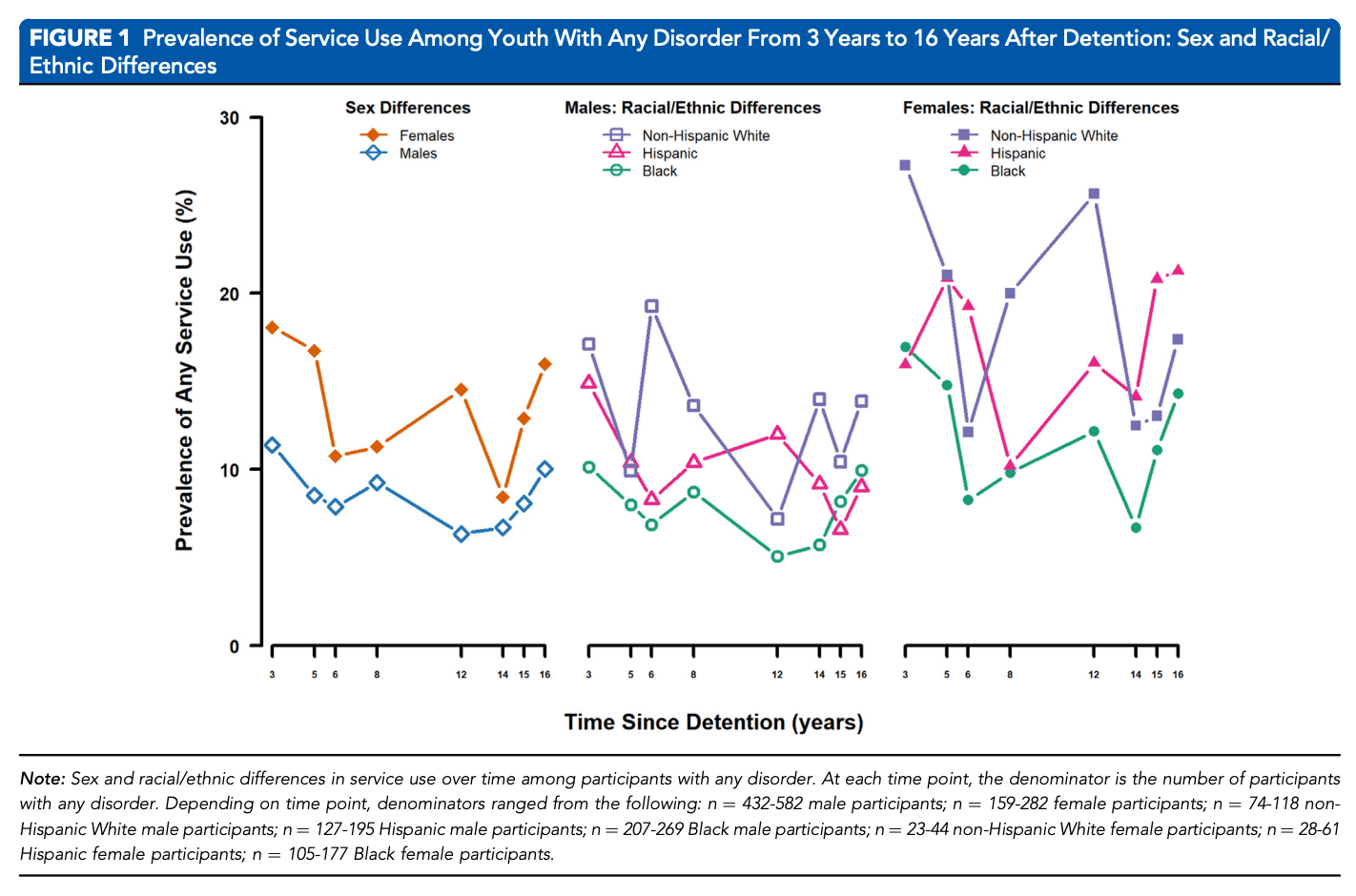

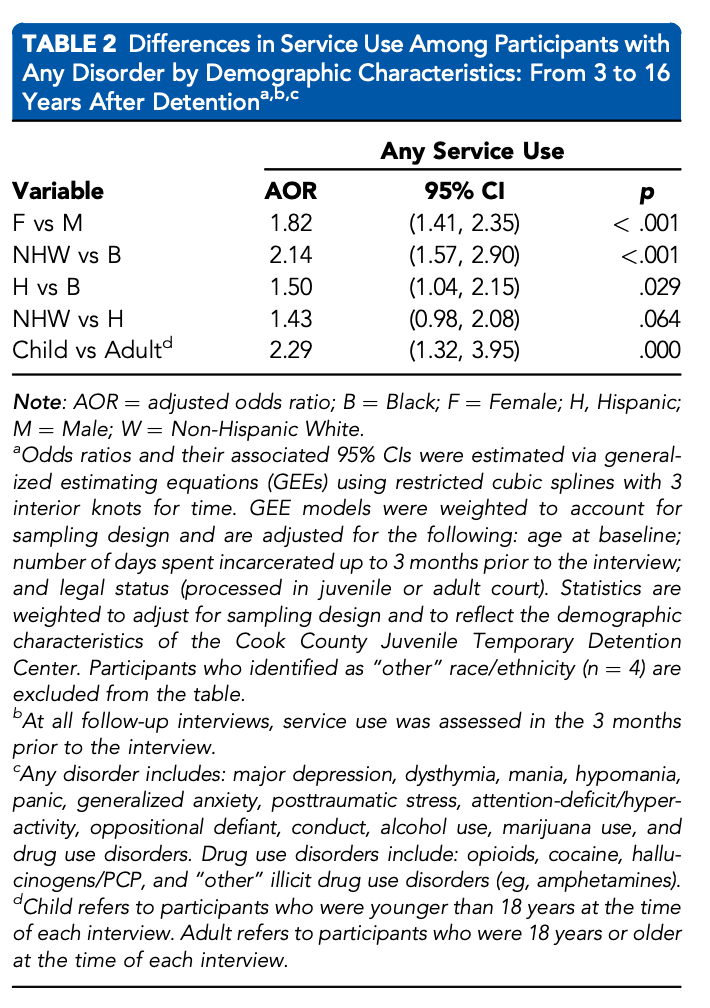

Sex and racial/ethnic differences in service use over time are shown in Figure 1. Table 2 shows odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that compare differences in service use over time by sex, race/ethnicity, age (child [<18 years] vs adult [18 years]), and presence of any past-year mental health or substance use disorder.

Differences by Demographic Characteristics

Differences by Sex. At all time points, less than one-fifth of male and female participants with any disorder received services (6.3%-11.4% of male and 8.5%-18.1% of female participants, depending on time point) (Figure 1). Female participants with any disorder had nearly twice the odds of receiving services compared with male participants with any disorder (OR ¼ 1.82; 95% CI ¼ 1.41, 2.35) (Table 2). For example, 5 years after detention, 8.5% of male and 16.8% of female participants with any disorder received services.

Differences by Race/Ethnicity. Compared with Black participants with any disorder, non-Hispanic White and Hispanic participants with any disorder had 2.14 (95% CI ¼ 1.57, 2.90) and 1.50 (95% CI ¼ 1.04, 2.15) times the odds of receiving services over time, respectively (Table 2). For example, among male participants with any disorder 3 years after detention, 17.1% of non-Hispanic White, 14.9% of Hispanic, and 10.2% of Black participants received services (Figure 1).

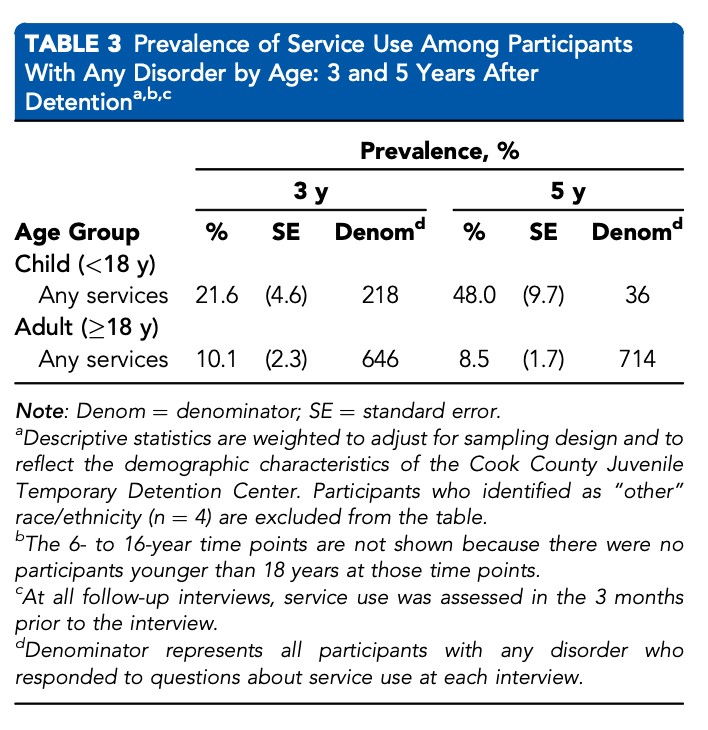

Differences by Age. People with a disorder were more likely to receive services during childhood (age <18 years) than during adulthood (OR ¼ 2.29; 95% CI ¼ 1.32, 3.95) (Table 2). For example, 3 years after detention, 21.6% of participants who were younger than 18 years received services, compared with 10.1% of those who were 18 years and older (Table 3).

Differences in Service Use by Type of Disorder

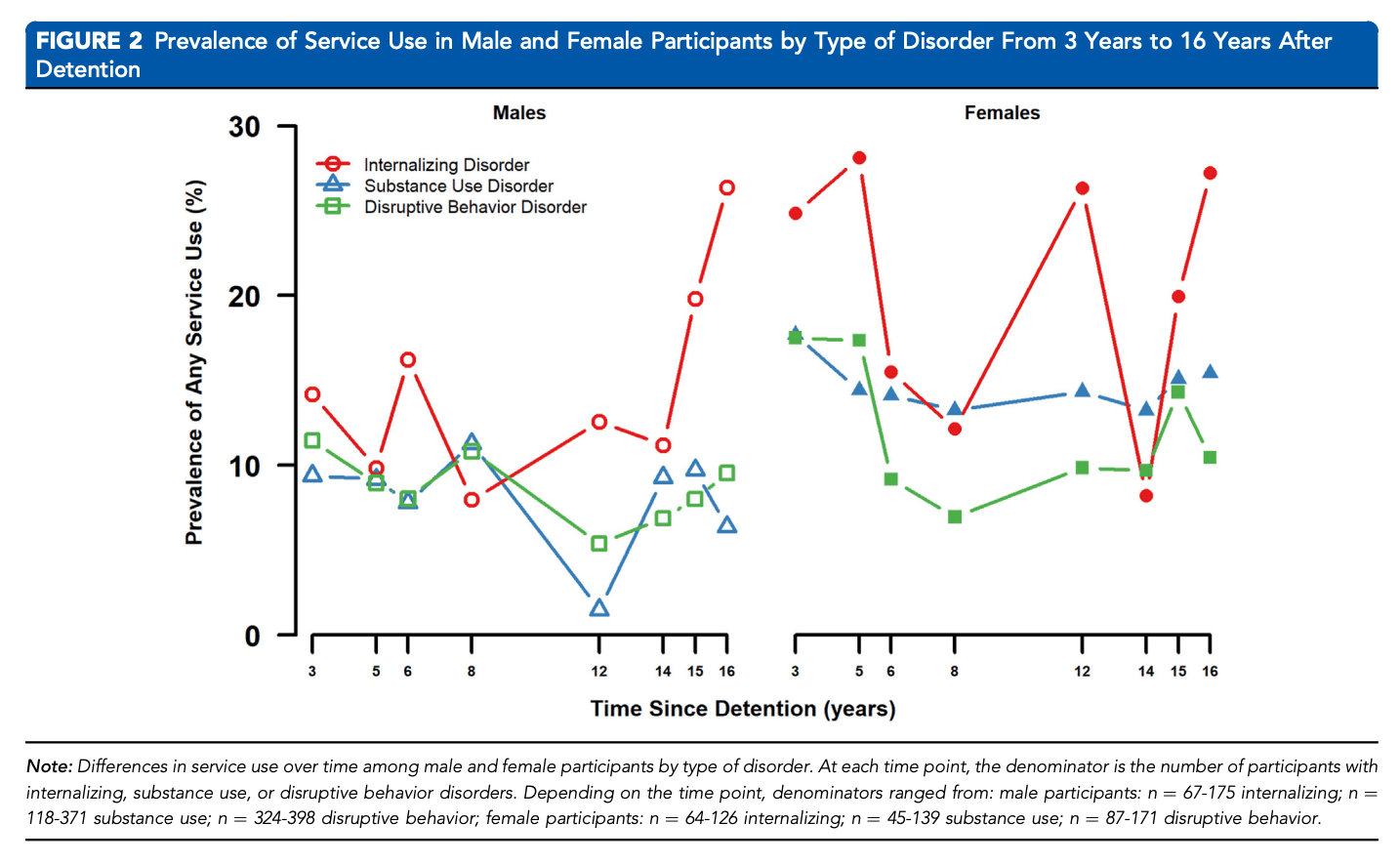

We investigated whether there are differences in service use depending on the type of disorder participants have as they age. For example, are participants with internalizing disorders more or less likely to receive services compared with participants with substance use disorders? Figure 2 shows the prevalence of service use among male and female participants with internalizing, substance use, and disruptive behavior disorders, respectively. Table S1, available online, presents ORs and 95% CIs comparing service use over time by type of disorder.

Internalizing Disorders vs Substance Use Disorders. Male and female participants with an internalizing disorder had 2.26 times and 2.43 times the odds of receiving services compared with those with a substance use disorder (respectively, 95% CI ¼ 1.26, 4.04; 95% CI ¼ 1.49, 3.97) (Table S1, available online).

Disruptive Behavior Disorders vs Substance Use Disorders. Male participants with a disruptive behavior disorder had 2.01 times the odds of receiving services compared with those with a substance use disorder (95% CI ¼ 1.18, 3.44) (Table S1, available online). Among female participants, there were no significant differences in the odds of receiving services (OR ¼ 1.23; 95% CI ¼ 0.73, 2.09).

Internalizing Disorders vs Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Female participants with an internalizing disorder had higher odds of receiving services compared with those with a disruptive behavior disorder (OR ¼ 1.97; 95% CI ¼ 1.25, 3.09) (Table S1, available online). Among male participants, there were no significant differences in the odds of receiving services (OR ¼ 1.12; 95% CI ¼ 0.62, 2.04).

DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective, longitudinal study to examine whether youth who have mental health disorders receive needed services after they leave detention—and as they age. We found that fewer than 1 in 5 youth who needed services received them across any follow-up, up to a median age of 32 years. Service use is lower than that found in studies of the general population, for example, the National Comorbidity Study (41%)59 and the 2020 National Study on Drug Abuse and Health (46%).60

Our findings confirm that sex and racial/ethnic inequities found in studies of youth in the justice system8-10,12-17,19,61 persist with age. Female participants who needed services were twice as likely as male participants to receive them as they aged. Compared with Black participants, Hispanic and non-Hispanic White participants had 1.50 and 2.14 times the odds of receiving needed services over time, respectively. What barriers contribute to these inequities? Compared with female and non-Hispanic White individuals, male and Black individuals: (1) are less likely to be referred for services7,10,62; (2) may be less likely to seek services because they do not believe that they need services, fear stigmatization, or mistrust mental health professionals8 ; and (3) face greater structural and financial barriers, have fewer services available in their communities, and lack insurance and transportation.63-65

As in prior studies,7,10,16,66 we found that participants with any disorder were more likely to receive services during childhood than in adulthood. During childhood, parents, caregivers, and school and correctional personnel may advocate for children and help them to access mental health services.67-69 As youth age, parental and institutional involvement decrease.7,70,71 Moreover, as youth transition from pediatric services to those that serve adults, they experience many barriers: unstable insurance coverage, less family support, unemployment, and inadequate housing, all of which make it challenging to navigate service systems.71-75

We also found that diagnosis mattered: participants with internalizing disorders were more likely to receive services than those with substance use disorders or disruptive behavior disorders (female participants only). The observed inequities may be the consequence of the stigma that many mental health providers have toward individuals with disruptive behavior and substance abuse disorders.76-80 Our findings are concerning—substance use and disruptive behavior disorders are the most prevalent disorders among youth and adults in the justice systems.1,2,20,31,43 Moreover, persons with these disorders are more likely to recidivate than those with internalizing disorders.2,26,27,30,31 Inequities in service provision may thus contribute to the revolving door between the justice system and the community.

Our findings are subject to the limitations of self-report. It was not feasible to collect record data because participants received services from many different providers in community and correctional settings (including Illinois, other states, and other countries). Although the CCJDC’s sociodemographic composition during data collection was similar to detention centers in other large cities, our findings may not be generalizable to detained youth in other locations, for example, rural areas and smaller cities.81 Follow-up data were collected only up to 2015. Despite the age of the data, our findings are relevant because sex and racial/ethnic inequities continue to burden youth and adults in the justice system.82,83 Although the Northwestern Juvenile Project had high participation rates, participants who were lost to follow-up may have been either more or less likely to have a disorder and to receive services.

We defined “need for services” as having a past-year mental health disorder at the time of the interview. As this is a conservative definition, we likely underestimated the proportion of youth who needed services at each time point. We had insufficient power to examine how the type of drugs used affected service use. We also did not analyze auxiliary services (eg, from religious leaders and support groups) because few participants used them. Although disorders were assessed during the past year prior to each interview, service use was assessed in the 3 months prior. It is possible that participants received services before service use was assessed. We could not assess for differences in service use by socioeconomic status because there was little variability: nearly all study participants had economic disadvantage. We did not assess gender identity. Despite these limitations, our findings have critical implications for public health.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Public Policy

1. Increase Engagement and Retention in Services. We must improve youth’s mental health literacy—the knowledge and attitudes needed to prevent, recognize, and seek treatment for disorders.84,85 Many youth in the justice system believe that their mental health problems will resolve on their own,8 minimize the severity of their disorders,86,87 do not know how to seek help,8,86,88 or perceive services to be ineffective.87 We must educate clients about disorders and the treatments that are available. These interventions will improve mental health literacy, normalize mental health and substance abuse problems, and facilitate service use.80,89-92

2. Train Providers to Use Culturally Competent Interventions. Youth in the justice system may be reluctant to seek mental health services because they do not trust providers and fear being stigmatized by them.87,93-96 Female youth and those who identify as persons of color are the least likely to trust service providers.19,87,97 Black and Hispanic youth mistrust providers who do not acknowledge that systemic racism, oppression, racial trauma, and discrimination affect mental health.87,98-100 We must train psychiatrists, other mental health providers, and correctional staff to address their implicit biases and to implement culturally competent, trauma-informed, and race-informed mental health care.82,87,98-101

3. Improve Linkages Between Service Systems. Many correctional stays in juvenile detention (median stay, 36 days) and in adult jails (average stay, 25 days) are too brief to provide effective mental health services.102,103 Linkages are critical: during incarceration, people will have lost contact with service providers in their communities.104-106 Yet, at least one-half of youth and adults who need services in corrections are not referred to community-based services upon release.107-109 Insufficient linkages have consequences: recidivism, problematic substance use, overdose, and premature death.29,109-112 There are now models designed to improve linkages between correctional and community services: for example, the Juvenile Justice Behavioral Health Services Cascade69; SAMHSA’s Guidelines for Successful Transition of People withMental or Substance Use Disorders from Jail and Prison113; and the Sequential Intercept Model.114-117 These models guide correctional facilities on ways to do the following: to increase enrollment in insurance74,75,118-122 and social services111,114,123; to plan for discharge prior to release from corrections71,107,114,123 and to contact community-based service providers prior to release107,114,123; to improve the transition from the systems that serve youth to those that serve adults71,124; and to increase interagency coordination of care.71,118,121,122,124-127

4. Expand Medicaid to Cover Services for Incarcerated Individuals. Currently, Medicaid does not reimburse correctional facilities for the cost of providing mental health and substance use services,119 limiting their ability to provide needed services.97,99 Although expanding Medicaid is costly,128,129 services will reduce recidivism114 and ultimately reduce overall costs.114,130 Psychiatrists and other mental health providers must advocate for the expansion of Medicaid. Only with adequate funding can correctional facilities provide high quality, evidence-based services for youth and young adults.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act mandates that mental health and substance use services be considered as essential medical treatments.119 Yet, we found that fewer than 1 in 5 youth in the justice system who needed mental health services received them as they aged. Male and Black participants were least likely to receive needed services, inequities that persisted as they aged. To eliminate inequities in mental health service use, psychiatrists, other mental health providers, and policy makers need to reduce the barriers to services in the community and in correctional settings.