Abstract

Objective: The movement to end mass incarceration has largely concentrated on people serving shorter sentences for non-violent offenses. There has been less consideration for the 1 in 7 people in prison serving life sentences, overwhelmingly for violent offenses, including those serving juvenile life without parole (JLWOP). Recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions result in a pressing need for data on second chance considerations for JLWOP. This study tracks outcomes of the national population of juvenile lifers. Data/methods: We cross-reference data to identify the JLWOP population at the time of Miller (N = 2904) to build a demographic profile and track resentencing, release, and mortality statuses. Statistics and data visualization are used to establish national and state-level baselines. Results: Findings reveal more than 2500 individuals have been resentenced and more than 1000 have been released. There is notable state variation in the number of JLWOP sentences, the extent to which JLWOP is still allowed, sentence review mechanisms, and percentage of juvenile lifers released. Conclusions/implications: The present study provides an important foundation for subsequent work to examine equity in the implementation of Miller and Montgomery within and across states, and to study reentry of an aging population that has spent critical life stages behind bars.

1. Introduction

The United States (U.S.) has one of the world's highest incarceration rates, with almost two million people currently incarcerated in state and federal prisons and jails (Prison Policy Initiative, 2023; World Prison Brief, 2024). The nation's dependence on incarceration over the last five decades is more than five times what it was 50 years ago (Ghandnoosh, 2023) and a reflection of the social-political climate (e.g., war on crime, super-predator theory, expansion of access to firearms) of the late 20th and early 21st centuries (Alexander, 2012; Mills, Dorn, & Hritz, 2015; Yun, 2011). Life and long sentences are an important driver of the problem of mass incarceration as these sentences are issued at higher rates than anywhere else in the world (Seeds, 2022). Unlike short-term sentences, the effects of long sentences accumulate over time as persons spend decade(s) in prison, if not their whole life.

Currently, one of every seven people incarcerated in U.S. prisons is serving a life sentence—inclusive of life with parole (LWP), life without parole (LWOP), and virtual life sentences (typically defined as 40+ years; U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2015)—and 54 % of the people incarcerated in U.S. prisons are serving a sentence of 10 years or more (Komar, Nellis, & Budd, 2023). Incarcerating individuals for long periods is generally unnecessary for public safety (Bersani & Doherty, 2018; Kazemian & Travis, 2015) and expensive for taxpayers (Mauer, King, & Young, 2004), with even higher correctional costs for aging populations (Luallen & Kling, 2014; Nellis, 2010). Research shows that effectively all those involved in criminal behavior eventually age out of this conduct (Sampson & Laub, 2005) and most do so in early adulthood (Bersani & Doherty, 2018). This phenomenon is particularly relevant for individuals serving life sentences who experience significant personal development and maturation over time (Johnson & Dobrzanska, 2005; Johnson & Leigey, 2020; Johnson, Rocheleau, & Martin, 2016). As a result, they often become different people from who they were at the time of their offense. Hence, life and long sentences contradict prevailing wisdom on community safety (Bersani & Doherty, 2018; Kazemian & Travis, 2015) and contribute to the “graying” incarcerated population problem (Reimer, 2008; see also Pew Charitable Trusts, 2014).

National efforts to end the crisis of mass incarceration have largely focused on the decarceration of people imprisoned for non-violent felony offenses (Daftary-Kapur & Zottoli, 2020; Kazemian & Travis, 2015), with less focused consideration of individuals serving long-term sentences for violent crimes—even though more than 60 % of persons in state prison have a conviction for a violent offense (Carson, 2018). Consideration of second chances is further diminished for those serving life sentences for acts of homicide. However, two landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions have mandated second chance considerations for individuals who were convicted of homicide as children and sentenced to juvenile life without the possibility of parole (JLWOP: Miller v. Alabama, 2012; Montgomery v. Louisiana, 2016). A JLWOP sentence is a type of life sentence given to minors (those under age 18) convicted of homicide offenses and subsequently tried in adult criminal courts. JLWOP sentences increased dramatically during the “tough on crime” era of the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting a societal stance that categorized these youth as exceptionally dangerous and implying that they should never rejoin society. Across the forty-four states that permitted JLWOP pre-Miller, it is estimated that nearly 12,000 people have been sentenced to life for offenses committed as children, under the age of eighteen at the time of their offense (Mauer & Nellis, 2018; The Sentencing Project, 2017, The Sentencing Project, 2018). Of these, past estimates indicate that there are more than 2000 juveniles serving life without the possibility of parole and nearly 10,000 juveniles serving LWP and virtual life sentences (Mauer & Nellis, 2018; The Sentencing Project, 2017, The Sentencing Project, 2018).

Globally, the United States is the only developed nation in the world that sentences children to life without parole (JLWOP), which directly conflicts with provisions of international law, including Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child that prohibits life sentences for juveniles (Parker, 2005). Sentencing children to life without parole (JLWOP) is a major human rights issue (Butler, 2010; Daftary-Kapur & Zottoli, 2020; Mauer & Nellis, 2018; Nellis, 2012; Parker, 2005). Recently, the UN Human Rights Committee has urged the U.S. to implement a moratorium on life imprisonment without the possibility of parole—for all ages—and to abolish these sentences for juveniles. This call is part of wider concerns regarding human rights abuses, notably the disproportionate impact on individuals of African descent (Center for Constitutional Rights, 2023).

Few studies have empirically examined people sentenced to JLWOP, and most reports on this population have been prepared for awareness and advocacy initiatives (Daftary-Kapur & Zottoli, 2020; Nellis, 2012; Parker, 2005). For example, a seminal analysis of JLWOP was prepared by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International in 2005 and was the first to report that the United States was the world's leader in sentencing children to spend the rest of their lives in prison for acts of homicide (Parker, 2005). The most comprehensive national tracking efforts to date are produced by advocacy organizations, including The Sentencing Project and The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth that have influenced policy and legislation around JLWOP as well as other efforts to reduce mass incarceration. These endeavors have resulted in important knowledge about the life histories of juvenile lifers prior to incarceration (e.g., family abuse, educational failure, socioeconomic disadvantage, racial disparities), as well as descriptions of their lives and prevailing disparities while incarcerated (Nellis, 2012) and have contributed to banning extreme sentences for children in the U.S., including JLWOP (CFSY, 2020). Otherwise, recent empirical research on the JLWOP population and JLWOP reform has come largely from small-scale, single-state or -locality studies, which are limited in scope (e.g., Abrams, Canlione, & Applegarth, 2020; Bennett, 2022; Brydon, 2021; Daftary-Kapur & Zottoli, 2020; Kokkalera, 2022; Ouellet & Wareham, 2023).

While the above-referenced works are highly informative, the national picture of the JLWOP population remains “pixelated” (Vannier, 2018) and incomplete. This gap is particularly concerning given the accumulation of juvenile lifers in prison pre-Miller, highlighting a significant omission in research literature that lacks a comprehensive inventory of national-level data on the lives of juvenile lifers (Parker, 2005).1 The absence of academic documentation has led researchers to depend on the writings of journalists, advocacy organizations, and the incarcerated. These sources have been informative and useful for early advocacy related to JLWOP sentences but do not offer a complete picture (Wacquant, 2002). The present study offers the most comprehensive national tracking effort of the JLWOP population to date. For the first time, by supplying concrete numbers, we provide a window into the full demographic profile of this population along with current resentencing and release statuses, and other key outcomes including mortality and exonerations. Further, we also offer time-series views into core outcomes, and consider variation in state-level policy contexts and resentencing mechanisms.

2. Policy landscape in the aftermath of Miller and Montgomery

In Miller v. Alabama (2012), the court ruled mandatory JLWOP sentences were unconstitutional, invalidating sentencing schemas requiring LWOP regardless of the defendant's age. Following Miller, sentencers must consider youth and related characteristics as mitigating evidence before imposing a JLWOP sentence. The court further instructed that JLWOP would likely be unconstitutionally disproportionate for the vast majority of youth. Four years later, the court instituted retroactive sentencing eligibility for people serving JLWOP sentences pre-Miller (Montgomery v. Louisiana, 2016). Prior research estimated that this ruling applied to more than 2000 people serving such sentences across 43 jurisdictions (Liem, 2016; Mills et al., 2015; Rovner, 2020), though the exact numbers vary by reporting source. Despite the clear federal mandates of Miller and Montgomery, little guidance for how to comply was provided to states. Each jurisdiction was left to create their own sentencing, parole, and sentence review policies, leading to the potential for wide variation in Miller's and Montgomery's implementation.

The implementation of policies in the wake of Miller and Montgomery is disparate across states—based in part on underlying pre-Miller sentencing schemes, state supreme court decisions post-Miller and Montgomery, and subsequent state legislative reform. For example, some jurisdictions, such as Alaska, Kansas, and Maine, did not utilize a mandatory life sentence scheme pre-Miller and did not have anyone serving a JLWOP sentence.2 Several states such as Massachusetts, West Virginia, and Texas banned the use of mandatory JLWOP sentences both prospectively and retroactively post-Miller but pre-Montgomery, while others (e.g., Colorado, Kentucky) banned the use prospectively. Still other states (e.g., Georgia, Washington, Wisconsin) retained JLWOP's discretionary use. After Montgomery, a slew of additional reforms were adopted, with additional states moving to ban JLWOP's use and other states passing legislation ensuring that the factors associated with Miller are incorporated into any decision to impose JLWOP. However, the Jones v. Mississippi decision in 2021 held that separate fact finding of a minor's permanent incorrigibility is not mandated to justify the imposition of LWOP in a state retaining discretionary use.

State variations in sentence review mechanisms and release decisions for retroactive JLWOP cases are also notable. For example, some states, such as Michigan, resentence cases one by one in a process requiring a judge to review each case in a courtroom to determine if an individual will be resentenced to a term of years or to LWOP again (Michigan Judicial Institute, 2020). In contrast, the state legislature in neighboring Ohio granted parole eligibility to everyone serving a JLWOP sentence prior to Miller, permitting the regular parole process to determine who should be released and when (Senate Bill 256, 2021). Maryland, as another example, removed JLWOP as a sentencing option and uses a process of retroactive judicial review in which judges are tasked with determining whether and how to modify a sentence for anyone sentenced to more than 20 years for crimes committed as a minor (Public Act 61, 2021).

Second look policies, often referred to as ‘second chance reforms’ (Murray, Hecker, Skocpol, & Elkins., 2021), have evolved considerably since Miller and Montgomery, even within the same jurisdiction over short intervals. California, for example, carved out the possibility for people serving JLWOP to apply for a resentencing hearing in California Senate Bill 9 (2012). In 2017, California Senate Bill 394 granted automatic eligibility for a specialized Youth Offender Parole Hearing (YOPH) for all people serving a JLWOP sentence at 25 years served. SB394 also extends YOPH for people serving life sentences for crimes committed when they were under age 25 and all provisions apply retroactively (Abrams, Canlione, Ouellet, & Melillo, 2023). While we focus on the JLWOP population in the present study, these examples highlight the potential for JLWOP policy to influence sentencing, second chances, and parole policies for other groups serving long sentences as well.

Systematic study of this population and the policies guiding the sentencing of children for violent offenses is warranted as the Miller and Montgomery decisions have propelled the JLWOP population to serve as a de facto test case for safe and equitable decarceration efforts of individuals who were convicted of acts of homicide committed as juveniles—considered by society to be the most dangerous persons and deemed unsuitable to ever reenter the community. A more complete picture and systematic documentation of the statuses of the juvenile lifer population, as well as the national policy landscape, is essential for ongoing policy reform, public safety considerations, and empirical research related to life and long sentences—key drivers of the problem of mass incarceration. The present study merges data from databases compiled by The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth and The Sentencing Project to identify the national population of individuals sentenced to JLWOP at the time of Miller and track their resentencing and release statuses, while also documenting state-level variations in the policy landscape related to JLWOP sentencing post-Miller.

3. Current study

The current study fills a critical need to understand the current resentencing and imprisonment status of the juvenile lifer population—at national and state levels. Systematic study of the JLWOP population has the potential for important applied implications for sentence modification and reentry policies and practices, as well as for advancements in understandings about life-course dynamics among those who have spent decades in prison. Several research objectives help to establish a necessary baseline that future empirical and policy work can build upon. First, we describe the demographic profile (e.g., race, gender, current age, age at offense, offense classification) of the national population of individuals sentenced to JLWOP pre-Miller. Second, we describe the current resentencing statuses, along with resentencing mechanisms and resentencing outcomes, and release statuses of the JLWOP population. In doing so, we document how frequently JLWOP is reimposed during resentencings, and whether resentencing mechanisms are connected with release outcomes. Third, we document the number of individuals who have been awarded retrial, commuted, exonerated, and/or have died. Fourth, we to analyze JLWOP offenses, resentencings, releases, and morality of this population over time in historical context. Finally, we analyze state variation in current statuses of JLWOP, usage, resentencing, and release statuses.

4. Data & methods

4.1. Data

In this study, we use two types of data. The first type of data includes individual-level data from an active archival data collection effort on the entire known national population of those sentenced to JLWOP pre-Miller (N = 2904).3 To assemble the tracking database, a variety of data sources were compiled including official DOC records, dockets, court decisions, information gathered from attorneys, online databases (e.g., VINELink), and newspaper articles.4 This active archival data collection includes information on a variety of factors such as demographics (e.g., age, sex race, date of birth), geographical details (e.g., county, state), offense characteristics (e.g., date of offense, age at offense, number of victims), resentencing information (e.g., date of resentencing, resentencing mechanism(s), and resentence ranges), exoneration status, release status, and mortality. Second, we supplement the archival data with state-level data gathered through ongoing policy analysis, in which state-level legislative statutes and supreme court rulings are tracked to measure the extent to which JLWOP sentences are allowed in each state (i.e., “policy surveillance”; see Burris, Hitchcock, Ibrahim, Penn, & Ramanathan, 2016). In particular, we aggregate several variables from the individual-level archival database to the state level and merge these with policy surveillance data on JLWOP ban status across the nation—enabling a window into the resentencing and release statuses of individuals within the policy contexts in which they occur. As both policies and individuals are moving targets, we note that all data were last updated in January 2024.

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Demographics

Race is a nominal variable: White (0), Black (1), Hispanic (2), and Other (3); other is a combined category of Asian and Native American as frequencies for these two racial groups were less than 2 % and 1 % of the population, respectively. Sex is a dichotomous variable: female (0) and male (1); we did not have any other information about sex or gender. Current age and age at offense are both measured in years. Offense, resentencing, release, and death dates are coded in years enabling a time-series view into these variables. First degree murder is a binary indicator of whether the individual was convicted of: second/ third degree murder (0), or first-degree murder (1).5

4.2.2. Criminal justice data

Resentencing status is a nominal variable categorizing the current status of juvenile lifers into three groups: not yet resentenced (0), resentenced (1), and other (2). It should be noted that we interject additional nuanced information in the results when discussing descriptives for the resentencing status measure as appropriate. Resentencing mechanism is a nominal variable indicating how juvenile lifers' received consideration for sentence modification: judicial decision (0), legislative relief6 (1), resentencing (2), multiple (3), and other (4). Minimum sentence is a nominal variable that categorizes juvenile lifers who have been resentenced into five groups: 0 to <25 years (0), 25 to <40 years (1), virtual life or 40+ years (2), life-reviewable (3), and life (4).7 Release status is a dichotomous variable indicating whether an individual has been released from prison and is coded: not released (0) and released (1). As with resentencing status, we interject additional information to clarify who has been released through traditional mechanisms as compared to commutation and exonerations. To enable a more nuanced view of the population, we include several dichotomous indicator variables that are not fundamentally mutually exclusive: awarded retrial, commuted, exonerated, deceased, and ineligible/affirmed/relief denied. The latter of these dummy variables is a combined indicator of whether an individual had their relief denied by a court reviewing their eligibility, were found to be ineligible for resentencing or parole eligibility under the amended statutory scheme, and/or the courts affirmed the JLWOP sentence. All of these indicator variables are coded 0 when the status is not present (e.g., not deceased) and 1 when it is present (e.g., deceased). Cause of death is a nominal variable: homicide (0), suicide (1), illness/natural cause (2), and unknown (3).

4.2.3. Policy-level data

JLWOP ban status is a nominal measure indicating the current extent to which JLWOP has been limited in each state and is coded: Discretionary (0), Banned (1), Banned (Prospectively) (2), and Not in use (3).8

5. Analytic plan

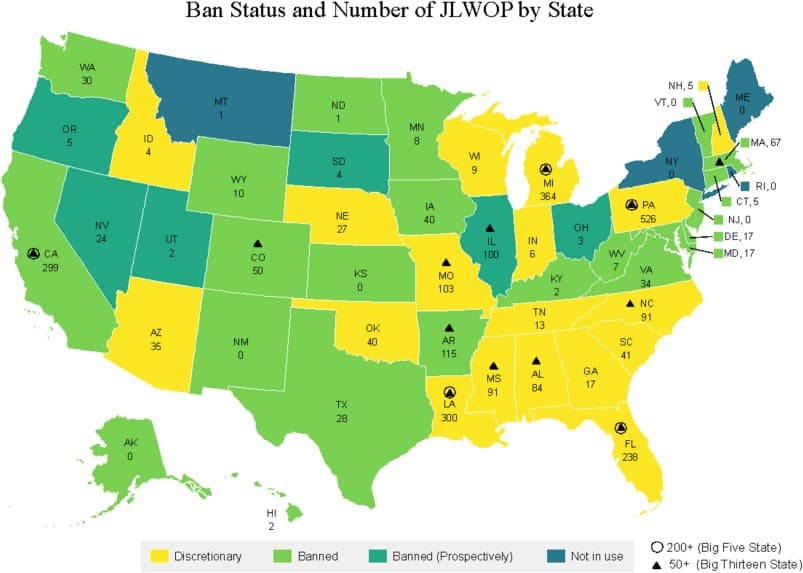

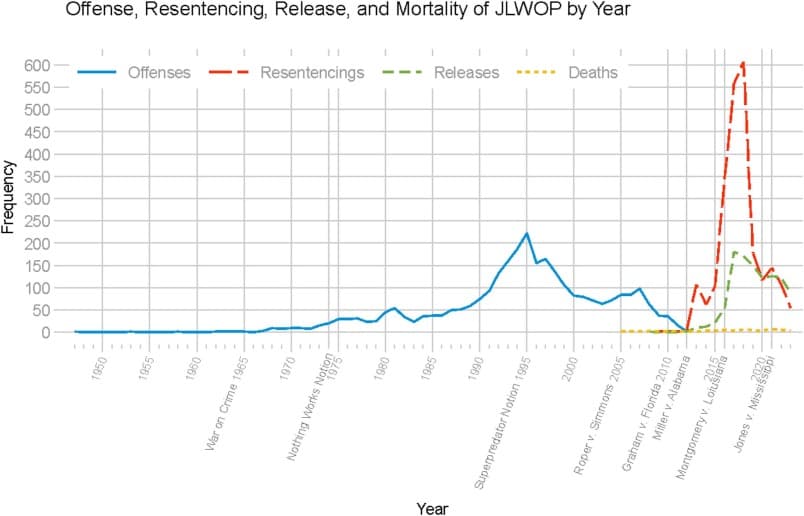

To describe the profile and carceral statuses of the U.S. population of juvenile lifers, we use several data visualization and statistical methods. We begin with a table of descriptive statistics and interlace this with findings from bivariate analyses. We then highlight differences in usage of JLWOP sentences and current policy practices across states by constructing a U.S. state map projected in Albers (with relocations for AK and HI). More specifically, we display current JLWOP ban status as of January 2024 alongside the total number of JLWOP in each state. This information is supplemented with an appendix of more detailed state-level breakdowns, including resentencing and release statuses by state and JLWOP rates per population (adjusted to 2020 U.S. Census) and corresponding state rankings. Finally, time-series line plots are used to provide a historical view of how offense, resentencing, release, and mortality has unfolded, given the sociolegal contexts of the times.

6. Results

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics on demographics, statuses, and mechanisms of the JLWOP population (n = 2904).9 The overwhelming majority of individuals who were sentenced to JLWOP prior to Miller are male (97.1 %). A strong majority of juvenile lifers are Black (61.1 %), with the remainder having official classifications of White (26.9 %), Hispanic (9.4 %), and Other (2.6 %, which is comprised of roughly 1.7 % Asian and 0.9 % Native American). While a large majority of those sentenced to JLWOP were convicted of a first-degree murder charge, nearly one in six (15.5 %) juvenile lifers received JLWOP from a conviction of second- or third-degree murder.10 Average age at the time of the offense was 16.3 years of age. A slight majority of individuals were 17 (52.7 %) at the time of the offense. About 32 % and 12 % of juvenile lifers were 16 and 15, respectively, at the time of the offense. Finally, a total of 3 % combined were just 13 or 14 years of age at the time of the homicide that led to their JLWOP sentence. The oldest living juvenile lifer is 86 whereas the youngest juvenile lifer sentenced pre-Miller is 27 years of age. The average juvenile lifer is 45.8 years old.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Profile and Statuses of the JLWOP Population

Frequency (%) or Mean (SD)† | |

|---|---|

Race/Ethnicity | |

White | 760 (26.9 %) |

Black | 1728 (61.1 %) |

Hispanic | 265 (9.4 %) |

Other | 75 (2.6 %) |

Sex | |

Female | 84 (2.9 %) |

Male | 2815 (97.1 %) |

Age† | 45.79 (9.23) |

Age at Offense† | 16.34 (0.82) |

First Degree Murder | |

Second/Third Degree | 450 (15.5 %) |

First Degree | 2449 (84.5 %) |

Resentencing Status | |

Not yet Resentenced | 279 (9.6 %) |

Resentenced | 2539 (87.4 %) |

Other | 86 (3.0 %) |

Resentencing Mechanism | |

Judicial Decision | 119 (4.8 %) |

Legislative Relief | 612 (24.5 %) |

Resentencing | 1729 (69.1 %) |

Multiple | 32 (1.3 %) |

Other | 10 (0.4 %) |

Minimum Sentence | |

0 to <25 | 398 (16.0 %) |

25 to <40 | 1536 (61.6 %) |

Virtual Life (40+) | 451 (18.1 %) |

Life (Reviewable) | 5 (0.2 %) |

Life | 102 (4.1 %) |

Release Status | |

Not Released | 1834 (63.2 %) |

Released | 1070 (36.8 %) |

Awarded Retrial | |

No | 2894 (99.7 %) |

Yes | 10 (0.3 %) |

Commuted | |

No | 2891 (99.6 %) |

Yes | 13 (0.4 %) |

Exonerated | |

No | 2873 (98.9 %) |

Yes | 31 (1.1 %) |

Deceased | |

No | 2829 (97.4 %) |

Yes | 75 (2.6 %) |

Ineligible/Affirmed/Denied | |

No | 2849 (98.1 %) |

Yes | 55 (1.9 %) |

Cause of Death | |

Homicide | 6 (8.0 %) |

Suicide | 9 (12.0 %) |

Illness/Natural Causes | 28 (37.3 %) |

Unknown | 32 (42.7 %) |

A large majority of the JLWOP population has been resentenced (87.4 %), but nearly 1 in 10 JLWOP (9.6 %) are presumed eligible but still awaiting resentencing. A relatively small number of JLWOP were classified as ‘other’ (3.0 %) as these individuals cannot or likely will not be resentenced based on the Miller and Montgomery rulings. More specifically, among the 86 cases classified as ‘other’, some were awarded a retrial (9.3 %), resentenced based on ineffective assistance of counsel prior to Miller (∼1 %), were commuted prior to resentencing (12.8 %), died prior to resentencing (51.2 %), were exonerated (24.4 %), or escaped and lived under asylum in another state and later passed away (∼1 %). It should be noted that of the 2539 who are currently classified as resentenced, 55 (2.2 %) of these individuals were denied relief, found to be ineligible for resentencing under statute, and/or had their JLWOP sentence affirmed in appellate courts.

Focusing on the sentence review mechanisms among those juvenile lifers who were resentenced, a sizeable majority underwent resentencing (69.1 %) where roughly one-fourth experienced blanket legislative relief (24.5 %). Less than 1 in 20 juvenile lifers were impacted by a state appellate judicial decision that was responsible for their sentence change (4.8 %). In a small handful of cases, often due to the rapidly evolving state policy landscape changes, juvenile lifers were flagged to have multiple resentencing mechanisms relevant (1.3 %) and, finally, a few odd cases were categorized as other (0.4 %).

Among juvenile lifers who have been resentenced, the most common minimum sentence category is 25 to <40 years in prison (61.6 %). Virtual life sentences (i.e., sentences of 40+ years) are the minimum sentence for about 18.1 % of individuals, whereas 0 to <25 years is the minimum sentence for 16 % of juvenile lifers that have been resentenced. It is important to note that life sentences are being reissued at relatively low rates; still, roughly 4 of every 100 individuals has received a new minimum sentence that is life (4.1 %) or life-reviewable (0.2 %).11 Overall, these sentence modifications are leading to a sizeable number of persons returning to the community, often after spending decades in prison.

As of January 2024, a total of 1070 individuals have been released, which comprises 36.8 % of those sentenced to JLWOP prior to Miller. More than 95 % of released individuals attained their freedom because of resentencing following the Miller/Montgomery rulings (n = 1033). However, about 5 in every 100 have returned to the community because they have been awarded a retrial that led to their freedom, had their sentence commuted, and/or were exonerated. We assess whether there are any associations between release and resentencing mechanism, particularly among the three key mechanisms of resentencing, legislative relief, and appellate judicial decision (see Table 2). Roughly 48 % and 46 % of the individuals whose sentence review mechanism was appellate judicial decision and individualized resentencing, respectively, have been released to date. By comparison, however, only 28 % of those who were resentenced through legislative relief have been released. A Pearson chi-square cross-tabulation analysis reveals that mechanism type is significantly associated with likelihood of release (X2 = 66.9, p < 0.001). More informatively, adjusted residuals analysis reveals that juvenile lifers who were resentenced through legislative relief are significantly less likely to be released (AR = −7.5, p < 0.001), whereas those whose mechanism was resentencing are more likely to be released (AR = + 7.59, p < 0.001), than would be expected by chance.12

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of release status by resentencing mechanism type.

Release Status | Resentencing Mechanism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Judicial Decision | Legislative Relief | Resentencing | Multiple | Other | Total | |

Not Released | 62 | 439 ↑ | 939 ↓ | 26 ↑ | 4 | 1470 |

52.1 % | 71.7 % | 54.3 % | 81.2 % | 40.0 % | ||

Released | 57 | 173 ↓ | 790 ↑ | 6 ↓ | 6 | 1032 |

47.9 % | 28.3 % | 45.7 % | 18.8 % | 60.0 % | ||

Total | 119 | 612 | 1729 | 32 | 10 | 2502 |

X2 = 66.94, p < 0.0001.First row has frequencies, and second row has column percentages. Cell significance in adjusted residual analysis: ↑ indicates cell higher than expected; ↓ indicates cell lower than expected. Resentencing mechanism missing for 37 cases.

It is important to note that about 1 in every 100 individuals in these data spent significant portions of their life course in prison for an offense in which they would be later be exonerated (n = 31). Commutations have occurred but have been used somewhat sparingly to date (n = 13) and a handful of individuals have been awarded a retrial (n = 10), each which typically, though not in all cases, has led to release. To date, a total of 75 juvenile lifers (2.6 %) are known to have died. Although the causes of death are currently unknown for about four in ten juvenile lifers who have passed away, available mortality data reveal that individuals sentenced to JLWOP have died from homicide (8 %) and suicide (12 %), as well as illness/natural causes (37.3 %).

The above aggregate national view provides a critical update current as of January 2024 on the overall status of resentencing and decarceration for the juvenile lifer population. In addition, it is important to describe fragmented policy approaches in the aftermath of the Miller and Montgomery decisions and to understand state variation in resentencing and release statuses. To begin, Fig. 1 is a U.S. state map that summarizes current ban status and the number of JLWOP in each state. Pennsylvania has the most juvenile lifers (526, 18.1 % of all JLWOP).13 There are five states (California, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania) that have more than 200 juvenile lifers each and, together, these “Big Five” states account for approximately three-fifths (59.5 %) of all juvenile lifers across the nation.14 There are eight additional states (Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Massachusetts) that have more than 50 juvenile lifers, with three of these (Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois) having over 100 juvenile lifers each. Collectively, these 13 states count for roughly five-sixths (83.6 %) of all juvenile lifers. We refer to this larger group of states as the “Big Thirteen.” As of January 2024, a total of 28 states (56 %) have banned JLWOP sentences. More specifically, twenty-two states (44 %) have outright banned JLWOP sentences while the remaining 6 states (12 %) have banned these sentences prospectively. In 18 states (36 %), JLWOP sentences are still allowed given judicial discretion. Finally, four states (8 %) are categorized as ‘not in use’ indicating that JLWOP is technically on the books but not currently used. Regarding the ban status of the states with the highest number of JLWOP, 80 % percent of the Big Five states and 69 % of the Big Thirteen states have discretionary JLWOP sentencing.

Fig. 1. Ban Status and Number of JLWOP by State

Appendix A supplements Fig. 1 with the rate of juvenile lifers per 1 million population, state rankings by JLWOPs per population, the percentage of individuals in each state that have been resentenced, and the percentage of JLWOP who have returned to the community. Among the “Big Five” states by total JLWOP counts, Louisiana (1st), Pennsylvania (2nd), and Michigan (3rd) maintain a top five status when adjusting for (2020 U.S. Census) population; however, Florida (12th) and California (20th) do not. Focusing on the Big Thirteen, there are notable differences among these states with respect to the percentage of individuals who have been resentenced and the percentage released. Regarding resentencing, with only rare exceptions for a few unique cases, everyone (99 %) in California has been resentenced. However, in Alabama and North Carolina, 65 % and 68 % have been resentenced, respectively; perhaps it is not surprising that these two states also notably lag other states in percentage released. Regarding release in the Big Five states, Pennsylvania and Michigan have each released more than 1 in 2 juvenile lifers, Louisiana more than 1 in 3, Florida about 1 in 5, and California about 1 in 7. Aside from a very small handful of unique cases that do not fit the mold in each of the Big 5 states, juvenile lifers in California experienced legislative relief, those in Florida, Michigan, and Pennsylvania were resentenced, and a healthy majority in Louisiana were resentenced though about a third experienced legislative relief. Legislation in Louisiana created a new discretionary sentencing scheme whereby prosecutors decided whether or not to seek LWOP at resentencing. If they did not seek LWOP at resentencing, the individual received eligibility as set out in the statute. If they did seek LWOP, the case proceeded to a resentencing hearing where the judge chose between LWP and LWOP. Importantly then, variation in both the resentencing and release statuses across states, alongside difference in states' chosen mechanisms to comply with the Miller and Montgomery rulings, points to the importance of building a better understanding of the degree to which state policy contexts shape equitable (or inequitable) resentencing and life course outcomes.

Fig. 2 provides a time-series window into the number of individuals each year who have an offense date that led to a JLWOP sentence prior to Miller, who have been resentenced, who have been released, and who have passed away. We include key court cases along with a few historical events along the timeline to help place these trends in context. The first JLWOP sentence stemmed from an incident in 1947. JLWOP was used sparingly for the next two decades; at the time of President Johnson's call for a War of Crime in 1965 there were just 10 total JLWOP sentences nationwide. Beginning in 1974, the year in which the famous Martinson’s (1974) “what works” paper was published, and continuing through 2010, incidents resulting in JLWOP were occurring at a clip of at least 21 per year, peaking at 222 per year in 1995, the year in which DiLulio advanced the super-predator notion (DiLulio, 1995). From 1995 onward, there was a general downward trend in JLWOP sentences until about 2003, followed by an uptick through 2007, and then a continued lessening of JLWOP usage up to the Miller decision.15

Fig. 2. Offense, Resentencing, Release, and Mortality of JLWOP by Year. Note: Data include those individuals sentenced to LWOP as minors pre-Miller.

Next, we focus on the number of resentencings occurring each year through any mechanism. There were only five JLWOP cases resentenced in 2012, with a majority occurring in that year, after the June 25th Miller ruling.16 However, over the three years leading up to the Montgomery decision, there were nearly 275 resentencings completed with more than 100 in 2013 and 2015. Findings reveal 350 resentencings in 2016, with all but a small handful coming after the January 25th Montgomery ruling—which opened the door for second chances to the full JLWOP population. Resentencing surged again in 2017 topping 550 that year and then peaked in 2018 eclipsing 600 before sharply declining in 2019. In 2016, the year of the Montgomery decision, 54 juvenile lifers were released bringing the total number released to 100. In 2017, the year with the most releases, more than 180 juvenile lifers across the nation returned to communities. More than 120 juvenile lifers have been released every year between 2017 and 2022, and in 2023 the cumulative number of JLWOP released eclipsed 1000.

Regarding mortality, data reveal that the first known death occurred in 2005. Up to and including the year in which the Miller decision occurred (i.e., 2012), there were five years in which a single individual passed away and three years in which there were multiple deaths. However, over the course of the next decade, there has not been a single year yet where multiple deaths have not occurred. Recall, individuals sentenced to JLWOP have died from homicide and suicide, as well as illness/natural causes. Taken together, the increasing mortality rate serves as both a reminder of the aging nature of this population and signals the importance of the need to study and understand complex mental and physical health (and safety) needs among those who have been incarcerated for long periods of the life course.

7. Discussion

The present study draws on important work (e.g., Mills et al., 2015; Nellis, 2012) to conduct the most comprehensive national tracking effort of the JLWOP population to date. Despite the significant role of advocacy organizations in spearheading national tracking efforts and accumulating valuable knowledge, a gap remains: prior to this study, the research literature lacks an all-encompassing national repository of data detailing the experiences of juvenile lifers, a notable omission given their increasingly prominent presence in prisons over recent decades (Parker, 2005). A comprehensive database is pivotal for enhancing our understanding of national decarceration efforts and for laying a solid foundation for future research, particularly in scrutinizing the equity of the implementation of landmark rulings like Miller and Montgomery. Our study makes a substantial contribution to the literature and breaks new ground by addressing several critical first-order descriptive questions about this national population.

The current study also presents the first national overview of the policy landscape related to JLWOP sentencing post-Miller. The findings unveil a landscape rife with disparities in resentencing and release practices across various states. Our concentration on the changing legal and policy contexts following the Miller and Montgomery decisions are a vital contribution and provide a more in-depth understanding of how state-level policies may be impacting the lives of those serving JLWOP sentences. Additionally, this study addresses the historical inattention from the research community, notably from criminologists, on individuals with life sentences. By comprehensively tracking the juvenile lifer population and state-level legislation related to JLWOP we offer statistics to both the criminological community and policymakers, to support criminal legal reform efforts. With these data, we hope to provide guidance for reform, specifically focused on the procedures of resentencing and the opportunities for release and reintegration of life-sentenced individuals. Moreover, this tracking effort provides a roadmap for following other populations serving life and long sentences on how to provide national and state-level snapshots and the policy landscape in these related areas. Although some of these efforts may be similar, researchers would need to consider how policies that influence JLWOP may spillover to influence these other populations as well, and consider other policies that more directly target those serving virtual or defacto life sentences.

7.1. Understanding the JLWOP population: ongoing analysis required

Our research signifies an urgent need for ongoing analysis of the JLWOP population, particularly concerning their legal statuses. As we navigate the evolving landscape following landmark legal decisions like Miller and Montgomery, continual monitoring and analysis of the JLWOP population is paramount. The present study offers a fundamental baseline of who these individuals are—their demographic makeup, the nature of their convictions, and their current carceral statuses—all of which are pivotal for developing tailored approaches to resentencing and reintegration.

Unsurprisingly, findings from our analysis reveal that an overwhelming majority of juvenile lifers are Black men consistent with previous studies, where JLWOP sentences are noted to be imposed on Black youth at rates up to ten times that of White youth (Maur & Nellis, 2018; Mills et al., 2015; Parker, 2005). Our study also shows that five states—California, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania (i.e., the “Big Five”)—have more than 200 juvenile lifers each and together, account for approximately 60 % of all juvenile lifers nationally, aligning with prior knowledge (Mills et al., 2015; Rovner, 2020). Eight additional states (Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Massachusetts) each have more than 50 juvenile lifers. With the Big Five included, these 13 states collectively account for almost 85 % of the nation's juvenile lifers. Beyond the state variation in the imposition of JLWOP sentences, we see significant variation in the ban status by state (see Fig. 1)17 as well as the rates of release by state (see Appendix A) and by time (see Fig. 2), illustrating a complex and dynamic policy and practice landscape. By tracking and describing the national population of JLWOP and associated policy landscape, this study sets a key baseline in the wake of the Miller and Montgomery decisions needed for future empirical work.

7.2. Policy perspectives on second chances: exploring effective strategies

The current study's findings underscore the potentially prominent role of state policies and their implementation in determining the fate of individuals sentenced to life without parole and highlight the importance of developing effective strategies for states to provide second chances to individuals serving life and extended sentences. For instance, results demonstrate variability in how states have responded to the federal mandates set by Miller and Montgomery, presenting both challenges and opportunities for policy reform. For example, California has effectively resentenced everyone. Other states, such as Alabama and North Carolina, have taken a slower approach with their resentencings with low rates of release that follow. Yet, the speed at which resentencings have occurred is not the only thing that contributes to reducing mass incarceration. The resentencing mechanism that a state uses—legislative relief vis-à-vis resentencing—was associated with an individual's chances of being released (see Table 2). The stark contrasts between states in their readiness to release individuals point to a fragmented approach to implementing post-Miller and Montgomery resentencing. However, it is unclear the degree to which the resentencing mechanisms or other factors such as parole board function, carceral contexts, or an incarcerated person's experiences and behavior contribute to these differences. More research is needed to understand individual and contextual factors that contribute to (in)equitable outcomes in resentencing and release.

State-level variation affects more than just legal or procedural aspects; it significantly influences social justice and equity, as well as the capacity and infrastructure available to support reentry and reintegration. The state-dependent nature of release opportunities raises ethical and legal concerns, especially as we see how geographic location appears to influence an individual's life trajectory—pre- and post-incarceration—thereby challenging the principles of fairness and uniform justice. For example, 28 states (56 %) have banned JLWOP sentences since Miller, though six states (12 %) only banned JLWOP sentences prospectively. In contrast, JLWOP sentences remain discretionary in 18 states (36 %), and in four additional states (8 %), JLWOP sentences are technically legal but are not actually in use.

In this way, the Miller and Montgomery decisions have positioned the JLWOP population as a key test case for assessing safe and equitable decarceration efforts for people convicted of homicide offenses. The findings in this study highlight a need for more research in service of developing equitable and effective policies, especially in states where resentencing and release practices are inconsistent or overly punitive. A comprehensive study of state policy decisions could yield significant applications for sentence modification, reentry policies, and practices—extending beyond minors recieving LWOP sentences. For example, Massachusetts recently established a landmark precedent by banning life without parole sentences for individuals under 21 years old in Commonwealth v. Mattis (2024), a decision that was consistent with scientific evidence that young adults also have a diminished capacity to fully understand the risks and consequences of their actions (Steinberg, 2008). Michigan is also hearing cases to rule against the use of LWOP sentences for those who committed homicide offenses at the age of 18 years old, and in Pennsylvania ongoing legislative debates aim to reform life without parole sentences for young people, particularly for certain types of homicide. Insights from the experiences of juvenile lifers could inform legislation extending the ending of life without parole sentences to young adults involved in homicide up to the age of 25. Effective second chance policies should balance public safety concerns with the potential for rehabilitation and recognize the unique developmental needs of individuals sentenced as youth. In the future, policy surveillance study (Burris et al., 2016) will allow us to provide further nuanced views on state-level variations in policymaking and highlight patterns in second chance reform measures. Systematically examining the variations in policy formulation and implementation around decarceration and second chances for juvenile lifers can facilitate recommendations for best practices, including for additional reform measures for JLWOP and other groups of lifers and people serving long sentences.

7.3. Limitations and directions for future study

National efforts to combat mass incarceration have primarily centered on decarcerating individuals convicted of non-violent felony offenses (Daftary-Kapur & Zottoli, 2020; Kazemian & Travis, 2015). Yet, there has been a lack of focus on those serving long-term sentences for violent crimes, a significant oversight given that over 60 % of state prison inmates are convicted of such offenses (Carson, 2018). This issue is particularly acute for those serving life sentences for homicide. To effectively address mass incarceration, it is imperative for criminal justice system actors and policymakers to reconsider the length of sentences being imposed for those whose actions are considered to warrant prison time, alongside other efforts to reduce prosecution or prison admissions where appropriate (e.g., progressive prosecution; see Davis, 2019).18 A key factor driving mass incarceration is the substantial increase in the duration of imprisonment, especially the rise in life sentences. Persisting with extreme sentences is inconsistent with evidence showing that prolonged incarceration offers minimal deterrent effects, tends to incapacitate older individuals who pose a diminished public safety threat, and is a significant financial strain (National Research Council, 2014)—further diverting resources from more efficacious public safety strategies. While we highlight the importance of decarcerating individuals convicted of violent offenses as a vital measure to address the widespread problem of mass incarceration, this study can only provide both a historical lookback and current national snapshot of an evolving landscape. This limitation underscores the need for a more dynamic, ongoing data collection and analysis mechanism; the next phase of research and policy development should focus on creating a national data dashboard. Such a tool would enable researchers, policymakers, and the public to access accurate, up-to-date information on individuals serving life sentences for violent crimes. Investing in this data infrastructure is essential for crafting targeted interventions that address the complexities of mass incarceration, ensuring that efforts to reduce the prison population are informed by a clear, comprehensive picture of those it comprises. Departments of corrections and related agencies play a crucial role in making data more accessible for researchers and policymakers in real-time. By improving data collection and sharing practices, these agencies can provide accurate and timely information that supports evidence-based decision-making and policy development, especially in relation to developing and implementing second chance policies.

As juvenile lifers reenter society, it is vital to understand the ramifications of prolonged confinement on their personal development and how this impacts their reintegration into society, especially as most transitioned from adolescence to adulthood while incarcerated. Research on the unique experiences of the very young and very old post-release is scarce (Laub & Sampson, 2003). Most studies have focused on the effects of long-term imprisonment within prison settings, centering on recidivism and basic social adjustment rather than exploring in-depth psychosocial changes (Kim, 2012; Kokkalera & Marques, 2022; Maur & Nellis, 2018; Mauer et al., 2004; Mears, Cochran, & Siennick, 2013; Weisberg, Mukamal, & Segall, 2011). Juvenile lifers re-entering society face numerous challenges, including limited access to public housing and employment opportunities (Bennett, 2022; Brydon, 2021; Daftary-Kapur, Zottoli, Faust, & Schneider, 2022; Franke, 2023; Travis, 2005), with older individuals encountering additional age-related discrimination in the job market (Kazemian & Travis, 2015; Liem, 2016). We also know that decades in prison can lead to significant health issues (Massoglia & Pridemore, 2015) and recent scholarship has drawn attention to the importance of meeting physical and mental health needs for better reentry success (e.g., Link, Ward, & Stansfield, 2019). Further, juvenile lifers are returning to a modern society that looks and functions very differently from the one in which they lived in during their adolescence. Taken together, future research should include comprehensive assessment of risk and protective factors, employment readiness, educational background, social supports, health and wellbeing, and carceral experiences. For those who have been released, barriers and facilitators to reintegration, the impact of criminal justice debt, and exploration of subjective experiences related to rehabilitation and reentry are needed.

8. Conclusion

In the wake of the landmark Supreme Court rulings in Miller and Montgomery, our research offers a critical national and state-level overview of JLWOP sentences in the United States. Our findings reveal significant disparities in resentencing and release processes across states, underscoring the pressing need for a comprehensive, national database to inform equitable decarceration efforts. Additionally, the study also highlights the evolving policy landscape's impact on juvenile lifers, advocating for continued analysis to ensure equitable implementation of these pivotal rulings. By documenting state-level variations in JLWOP sentencing, this research lays a critical foundation for future research and policy reform aimed at remedying inequities within the criminal justice system. Ultimately, we call for a collaborative effort among scholars, policymakers, and practitioners to develop and implement reforms that recognize the potential for rehabilitation and reintegration of juvenile lifers and to afford second chances for equitable and safe decarceration for those sentenced to life and other long sentences.

Funding statement

This research was made possible through the support from Arnold Ventures, aimed at conducting ‘A National Outcomes Study of Safe and Equitable Decarceration Among People Serving Juvenile Life Without the Possibility of Parole.’ The authors wish to extend their sincere appreciation for this financial support, which has been instrumental in facilitating the research activities leading to this publication. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Arnold Ventures.

State | State Rank (Count) | Number of JLWOP | State Rank (Rate) | JLWOP per 1 M Pop. | Percent Resentenced | Percent Released | State Ban Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pennsylvania | 1 | 526 | 2 | 40.5 | 92 % | 56 % | Discretionary |

Michigan | 2 | 364 | 4 | 36.1 | 90 % | 52 % | Discretionary |

Louisiana | 3 | 300 | 1 | 64.4 | 83 % | 39 % | Discretionary |

California | 4 | 299 | 20 | 7.6 | 99 % | 15 % | Banned |

Florida | 5 | 238 | 12 | 11.1 | 84 % | 21 % | Discretionary |

Arkansas

| 6 | 115 | 3 | 38.2 | 98 % | 58 % | Banned |

Missouri | 7 | 103 | 8 | 16.7 | 97 % | 43 % | Discretionary |

Illinois | 8 | 100 | 18 | 7.8 | 80 % | 58 % | Banned (Prospectively) |

Mississippi | 9 | 91 | 5 | 30.7 | 77 % | 35 % | Discretionary |

North Carolina | 9 | 91 | 15 | 8.7 | 68 % | 12 % | Discretionary |

Alabama | 11 | 84 | 9 | 16.7 | 65 % | 4 % | Discretionary |

Massachusetts

| 12 | 67 | 14 | 9.5 | 99 % | 54 % | Banned |

Colorado

| 13 | 50 | 16 | 8.7 | 86 % | 36 % | Banned |

South Carolina | 14 | 41 | 17 | 8.0 | 51 % | 2 % | Discretionary |

Iowa | 15 | 40 | 11 | 12.5 | 95 % | 57 % | Banned |

Oklahoma

| 15

| 40

| 13

| 10.1 | 72 %

| 12 %

| Discretionary

|

Arizona

| 17 | 35

| 21

| 4.9

| 17 %

| 3 %

| Discretionary

|

Virginia

| 18 | 34 | 23

| 3.9

| 97 %

| 21 %

| Banned

|

Washington

| 19

| 30

| 25

| 3.9

| 77 %

| 13 %

| Banned

|

Texas

| 20

| 28

| 37

| 1.0 | 93 %

| 0 %

| Banned

|

Nebraska

| 21

| 27

| 10

| 13.8

| 100 %

| 30 %

| Discretionary

|

Nevada

| 22

| 24

| 19

| 7.7

| 100 %

| 67 %

| Banned (Prospectively)

|

Delaware

| 23

| 17

| 7

| 17.2 | 100 %

| 53 %

| Banned

|

Georgia

| 23 | 17

| 30

| 1.6

| 71 %

| 0 %

| Discretionary

|

Maryland

| 23 | 17 | 27

| 2.8

| 100 %

| 6 %

| Banned

|

Tennessee

| 26

| 13

| 29 | 1.9

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Discretionary

|

Wyoming

| 27 | 10 | 6

| 17.3

| 100 %

| 50 %

| Banned

|

Wisconsin

| 28

| 9 | 31

| 1.5

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Discretionary

|

Minnesota

| 29 | 8

| 32

| 1.4

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned

|

Minnesota

| 29

| 8

| 32

| 1.4

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned

|

West Virginia

| 30

| 7

| 24

| 3.9

| 100 %

| 86 %

| Banned

|

Indiana

| 31

| 6

| 39

| 0.9 | 83 %

| 17 %

| Discretionary

|

Connecticut

| 32

| 5

| 33

| 1.4

| 80 %

| 40 %

| Banned

|

New Hampshire

| 32

| 5

| 26

| 3.6

| 80 %

| 0 %

| Discretionary

|

Oregon

| 32

| 5

| 36

| 1.2

| 60 %

| 40 %

| Banned (Prospectively)

|

Idaho

| 35

| 4

| 28

| 2.2

| 75 %

| 0 %

| Discretionary

|

South Dakota

| 35

| 4

| 22 | 4.5

| 75 %

| 25 %

| Banned (Prospectively)

|

Ohio

| 37

| 3

| 42

| 0.3

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned (Prospectively)

|

Hawaii

| 38

| 2 | 34

| 1.4

| 100 %

| 100 %

| Banned

|

Kentucky

| 38

| 2

| 41

| 0.4

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned

|

Utah

| 38

| 2

| 40

| 0.6

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned (Prospectively)

|

Montana

| 41

| 1

| 38

| 0.9

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Not in use

|

North Dakota

| 41

| 1

| 35

| 1.3

| 100 %

| 0 %

| Banned

|

Alaska

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Banned

| ||

Kansas

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Banned

| ||

Maine

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Not in use

| ||

New Jersey

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Banned

| ||

New Mexico

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Banned

| ||

New York

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Not in use

| ||

Rhode Island

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Not in use

| ||

Vermont

| 43

| 0

| 43

| 0

| Banned

| ||

Federal

| 39

| 97 %

| 33.3 %

| Banned

|