Abstract

Impulsive and risky decision-making peaks in adolescence, and is consistently associated with the neurodevelopmental disorder Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), regardless of age. In this brief review, we demonstrate the similarity of theoretical models explaining impulsive and risky decision-making that originate in two relatively distinct literatures (i.e., on adolescence and on ADHD). We summarize research thus far and conclude that the presence of ADHD during adolescence further exacerbates the tendency that is already present in adolescents to make impulsive and risky decisions. We also conclude that much is still unknown about the developmental trajectories of individuals with ADHD with regard to impulsive and risky decision making, and we therefore provide several hypotheses that warrant further longitudinal research.

Introduction

Reckless driving, trying drugs, having unsafe sex, or conducting criminal behavior: impulsive or risky decision making peaks during the adolescent years, and is observed disproportionately often in individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). This raises the questions (1) whether the presence of ADHD during adolescence further exacerbates the tendency that is already present in adolescents to make impulsive and risky decisions, and (2) whether going through adolescence further exacerbates the tendency that is already present in individuals with ADHD to make impulsive and risky decisions? The current review is centered on these two research questions.

While the real-life examples above are often interchangeably referred to as impulsive or risky acts, in psychological research, a distinction is made between impulsive and risky decision-making. Impulsive decision-making refers to a preference for small, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards. Risky decision-making refers to a preference for choices with a high variability in possible outcomes (i.e., large uncertain rewards) over choices with lower variability in potential outcomes (i.e., small certain rewards).

According to dual-system models, impulsive and risky behaviors peak in adolescence as result of an imbalance between two brain systems and their interconnections: (a) The early maturation of the affective system (involving ventral striatum, amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex) that subserves emotion and reward processing, and (b) the slower maturation of the cognitive control system (involving lateral prefrontal cortex and lateral parietal cortex). Similarly, the dual-pathway model of ADHD proposes two pathways that rather independently lead to the expression of ADHD symptoms: (a) a dysregulated cognitive control pathway (involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and dorsal striatum) characterized by weak response inhibition and executive dysfunctioning, and (b) a reward pathway (involving ventral striatum, amygdala, ACC, and medial prefrontal cortex) characterized by a shortened delay reward gradient. While there is clear overlap in the systems proposed to play a role in adolescence and ADHD, there are also important differences. While an imbalance between systems is proposed to be key during adolescence, ADHD models do not necessarily suggest an imbalance, but rather propose that “deficits” in either of these systems can form a pathway to ADHD. Further, while the role of the cognitive control system is suggested to be comparable in adolescence and in ADHD (in both cases, a slowly developing/immature cognitive control system), this is not the case for the affective system. Dual-system theories suggest that adolescence-induced hyperresponsivity of this system leads to reward-seeking behaviors, whereas the dual-pathway model of ADHD proposes a unique motivational style related to ADHD, characterized by delay aversion.

Impulsive decision making

Impulsive decision making is typically assessed with temporal discounting (TD) tasks, which involve choices between a small, immediate reward (e.g., $2 today), and a larger, delayed reward (e.g., $10 after 30 days). Studies that included participants from a relatively narrow age range showed that late adolescents choose less impulsively than early adolescents on TD tasks, that adolescents make less impulsive decisions than children, but they make more impulsive decisions than young adults. However, studies including participants with a wider age range found that adolescents were less impulsive than both children and young adults, which could reflect the fact that adolescents may be able to engage the cognitive control system more than children and young adults when they are motivated by rewards. Achterberg et al. found linear decreases in impulsive decision making with age in cross-sectional analyses, but non-linear (i.e., decreased impulsive decision making in adolescents compared to young adults) effects of age in longitudinal analyses. This suggests that longitudinal designs may be more sensitive to detecting subtle individual differences and developmental trajectories.

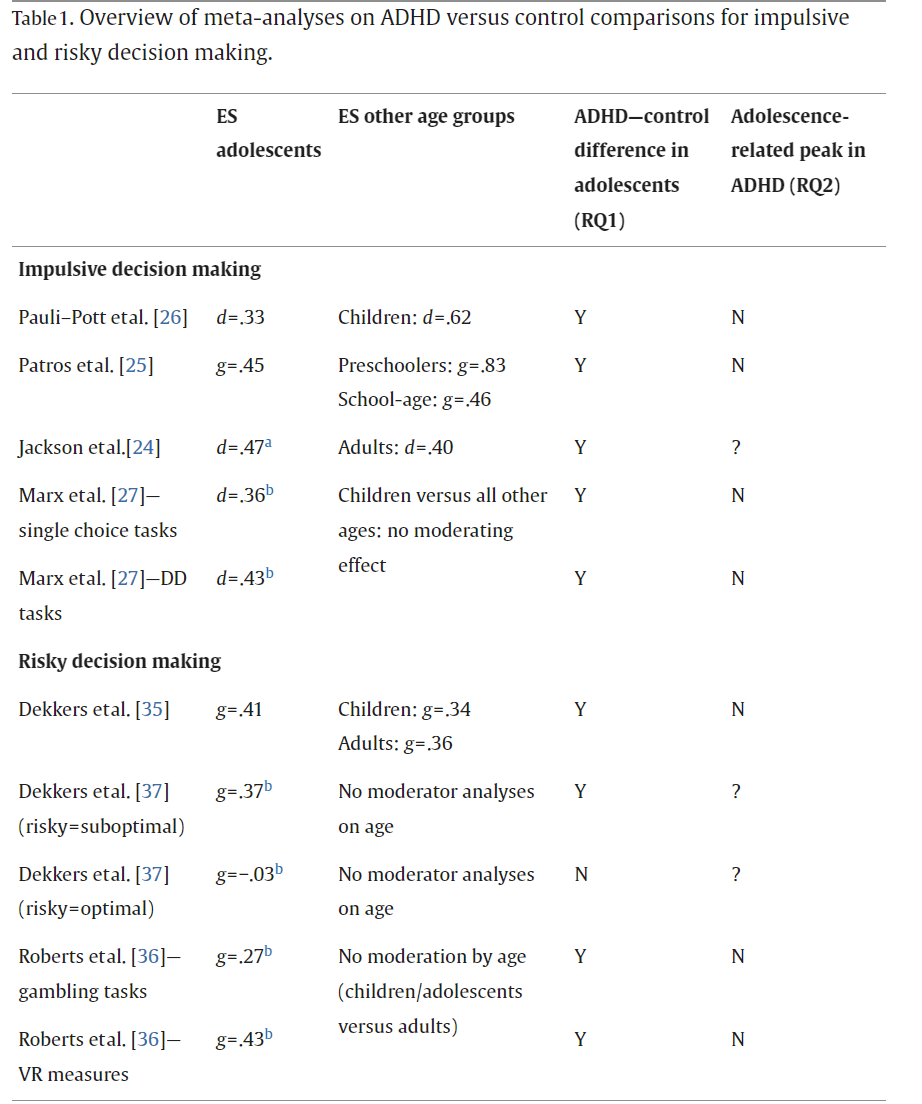

Four recent meta-analyses examined group differences between ADHD and controls on impulsive decision making measured with TD and/or single choice tasks. Patros et al. reported impulsive decision making in children and adolescents with ADHD relative to typically developing controls. Group differences were large for preschoolers, and medium for school-age children and adolescents. Similarly, Jackson et al. reported increased impulsive decision making in individuals with ADHD relative to controls. Effect sizes were similar for children, adolescents and adults. Pauli–Pott et al. performed a meta-regression to evaluate ADHD-control differences on impulsive decision making as a function of developmental transition periods. Based on previous findings reporting a peak in impulsive choice during mid-adolescence, they hypothesized that group differences would be smallest during this period because these would be obscured by the inter-individual variance induced by puberty. Indeed, the effect size was larger for children than for adolescents. Marx et al. reported an up-to-date meta-analysis on ADHD-control comparisons (all ages). Between-group differences were small on single choice paradigms and medium on TD tasks. Effects were not moderated by age, but adolescents were not treated as a separate group.

This consistent increase in impulsive decision making in ADHD is considered a consequence of delay aversion. Sonuga–Barke proposed that individuals with ADHD experience negative emotions during waiting, causing a desire to escape this. Indeed, several studies support this notion in adolescents with ADHD. For example, adolescents with ADHD discounted delayed rewards, but not effortful rewards, more steeply than controls, suggesting a specific role for delay aversion. This was accompanied by a delay-sensitive response in the amygdala for those adolescents with ADHD who were more delay averse in daily life. Similarly, Van Dessel et al. found that adolescents with ADHD, relative to controls, demonstrated delay-related increases in the amygdala following cues signaling impending waiting times, which was interpreted as signaling aversion to waiting. In a behavioral study, impulsive decision making was more strongly correlated with the subjective experience of difficulty waiting in adolescents with ADHD relative to adolescents without ADHD. This suggests that adolescents with ADHD based their (impulsive) choice more on how difficult it feels to wait than controls. Similarly, Mies and colleagues [32] found that delay aversion—but not reward sensitivity—drove impulsive choices on TD tasks in adolescents with ADHD. Marx et al. showed that delay, independent of reward, exacerbated impulsive decision making in ADHD, also supporting the crucial role of delay aversion.

Taken together, in answer to question 1, we conclude that adolescents with ADHD engage in more impulsive decision making on experimental tasks than adolescents without ADHD (see Table 1, RQ1). As for question 2, there is no evidence suggesting that going through adolescence exacerbates the tendency that is already present in ADHD to make impulsive decisions (see Table 1, RQ2). If anything, there is some evidence that impulsive decision making is less characteristic of adolescents with ADHD than of children with ADHD. Delay aversion appears an important contributing mechanism of impulsive decision making in adolescents with ADHD.

Risky decision making

Risky decisions are typically assessed with gambling tasks involving choices between low-risk options (e.g., high probability of small reward) and high-risk options (e.g., low probability of larger reward). A meta-analysis of experimental studies employing risky decision-making tasks showed that adolescents make more risky decisions than adults, but adolescents do not differ from children. Defoe et al. proposed that age differences in risk exposure (i.e., opportunities to engage in risky behaviors) might explain why adolescents show increased risk-taking compared to children in daily life, but not in experimental studies.

Adolescents with ADHD consistently engage in increased real-life risk-taking behavior relative to their typically developing peers. We discuss three meta-analyses summarizing all studies that compared groups with and without ADHD on gambling tasks, and we particularly focus on age-related differences.

The first meta-analysis found more risky decision making in groups with ADHD, with effects of small-to-medium size. Notably, the difference in risky choice between individuals with and without ADHD was similar across age. Second, an updated meta-analysis similarly observed a small-to-medium sized effect indicating increased risky decision-making in groups with ADHD. This meta-analysis distinguished between traditional gambling tasks and virtual reality (VR) measures of risky decision making, and demonstrated that group differences were larger when VR measures were used. For both types of outcome measures, age did not moderate the effects.

A third meta-analysis particularly focused on one underlying mechanism: suboptimal decision making. Groups with and without ADHD only differed in risky decision-making when risky decisions were suboptimal in terms of expected value, whereas there were no differences when risk taking was advantageous. This suggests that, at group level, individuals with ADHD rather show a tendency towards suboptimal decision making instead of an inherent risk proneness.

In conclusion, in answering question 1, ADHD is consistently associated with risky decision making, as indicated by three meta-analyses (Table 1). This effect was stable across age. There is no evidence for the notion that going through adolescence exacerbates the tendency to make risky decisions that is present in individuals with ADHD (question 2). Notably, the link between risky decision making and ADHD was limited to situations in which the risky choice was the suboptimal choice.

General discussion and future directions

We conclude that adolescents with ADHD show increased impulsive and risky decision making compared to typically developing adolescents (RQ1). Increased delay aversion in adolescents with ADHD may explain some of these group differences, particularly in impulsive decision making. There are many similarities between the neurobiological models of impulsive decision making developed for ADHD and for typical development, including the hypothesis that two interconnected brain systems play a role: an affective system and a cognitive control system. However, ADHD models emphasize that the affective system underpins both reward sensitivity and delay aversion while models of adolescence tend to focus on reward sensitivity alone. Nonetheless, recent research showed that in typically developing adolescents, impulsive decision making was associated with higher levels of delay aversion. Therefore, delay aversion may also be relevant for impulsive decision making in adolescents without ADHD.

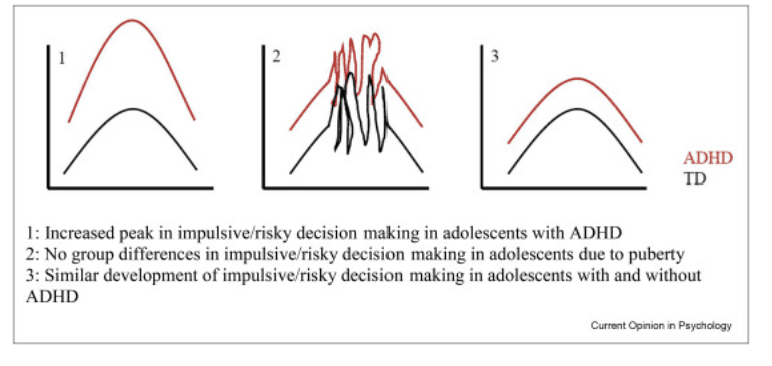

The second research question, whether the tendency to make impulsive and risky decisions in individuals with ADHD is exacerbated during adolescence, is harder to answer. Few studies have used a developmental perspective in research on ADHD. While ADHD is regarded a neurodevelopmental disorder, the majority of research compares individuals with ADHD with age-matched controls, thereby missing pivotal knowledge about the development of individuals with ADHD. While a cross-sectional approach is informative to identify ADHD-control differences in decision making in different age groups (see Table 1, RQ2), longitudinal research is needed to examine ADHD-control differences in developmental trajectories of impulsive and risky decision making. Delineating such trajectories will enable the identification of key developmental periods during which interventions may be particularly helpful. Additionally, it will enable the identification of key developmental periods of impulsivity- and risk-related opportunities such as creativity, curiosity, and starting new social contacts. The following hypotheses, following from the dual system models, may be formulated (also see Figure 1).

(1) The developmental trajectory as observed in typical adolescents, namely a peak in impulsive and risky decision making in adolescence as compared to childhood and adulthood may be exaggerated in individuals with ADHD, for example, due to the delayed maturation of the prefrontal cortex in these individuals.

(2) As proposed by Pauli–Pott et al., the peak in impulsive and risky decision making in adolescence may be obscured in individuals with ADHD because puberty-related changes contribute to more variability in decision-making, thereby obscuring group differences.

(3) The developmental trajectories of adolescents with and without ADHD are similar in shape, but adolescents with ADHD are higher in impulsive and risky decision making than adolescents without ADHD.

Figure 1

When addressing such hypotheses, it will be important to consider the use of more ecologically valid tasks, including not only rewards but also losses and effort costs, not only monetary but also primary and social rewards, and integrating temporal and probabilistic aspects in relevant contexts. Additionally, while intuitively related, not many studies investigated the direct link between impulsive and risky choice in adolescents with ADHD, as most tasks only capture one of these constructs. An exception is the Cambridge Gambling Task (CGT), which disentangles risk proneness, risk adjustment (i.e., the adjustment to changes in the level of risk) and delay aversion. A few studies used the CGT in samples with ADHD, although not in adolescents. In children, groups with and without ADHD did not differ in their risk proneness, but children with ADHD had more problems adjusting their bets to changes in risk, and showed increased delay aversion. Crucially, these aspects were correlated, which suggests that risky decision making in relation to ADHD is potentially driven by a different motivational style in which immediate rewards are preferred to escape delay, which aligns with the motivational part of the dual pathway model.

Clinical implications

The research reviewed here may also contribute to the development of interventions to reduce impulsive and risky decision making in adolescents with ADHD. Delay aversion seems to play an important role in impulsive decision making, and may contribute to risky decision making as well. Commonly used psychotherapies such as mindfulness and acceptance and commitment therapy were found to decrease impulsive decision making and risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, overeating) in typically developing young adults. Further, short-term interventions such as episodic future thinking (e.g., vividly imagining a valued delayed reward during decision-making) appear to reduce impulsive decision making in typically developing young adults. Future studies should investigate the effectiveness of these interventions in adolescents with ADHD.

Contextual factors are crucial when developing such interventions, as affective brain systems are particularly activated in the presence and under the influence of peers. Empirically, this is mirrored by many studies demonstrating that typically developing adolescents engage in increased impulsive and risky decision making in the presence and under the influence of peers. In the sole experimental investigation of susceptibility to peer influence in ADHD, adolescents with and without ADHD were equally susceptible to peer influence on risky decision-making, whereas there are no experimental studies yet on susceptibility to peer influence with regard to impulsive choice in groups with ADHD.

A final direction for clinicians is to not only consider negative aspects of impulsive and risky decision-making (also see study by Green et al.). In clinical practice, adolescents with ADHD often report positive forms of impulsive or risky behaviors, such as asking others on a date, talking with strangers or trying new hobbies. Yet, empirical evidence for these observations is lacking, and reviews on studies in typically developing adolescents suggest the opposite: positive and negative risk taking were generally negatively correlated or entirely distinct, and adolescents with low self-regulatory capacities showed more negative and less positive risk taking. Also, self-reported impulsivity was linked to negative but not positive risk taking.

In conclusion, we found that adolescents with ADHD make more impulsive and risky choices than age-matched peers on lab-based tasks, with delay aversion playing a key role. An important question to be answered is which developmental trajectories in impulsive and risky decision making individuals with ADHD follow, as compared to controls. Longitudinal research is needed, using ecologically valid tasks. Clinically speaking, knowledge about these trajectories will give insight into time windows of opportunity and intervention.