Abstract

Background: Significant disparities in substance use severity and treatment persist among women who use drugs compared to men. Thus, we explored how identifying as a woman was related to drug use and treatment experiences. Methods: The study recruited participants for a qualitative interview study in Boston and San Francisco from January–November 2020. Self-identified women, age ≥18 years, with nonprescribed opioid use in the past 14 days were eligible for inclusion. The study team developed deductive codes based on intersectionality theory and inductive codes generated from transcript review, and identified themes using grounded content analysis. Results: The study enrolled thirty-six participants. The median age was 46; 58% were White, 16% were Black, 14% were Hispanic, and 39% were unstably housed. Other drug use was common with 81% reporting benzodiazepine, 50% cocaine, and 31% meth/amphetamine use respectively. We found that gender (i.e., identifying as a woman) intersected with drug use and sex work practices and exacerbated experiences of marginalization. Violence was ubiquitous in drug use environments. Some women reported experiences of gender-based violence in substance use service settings that perpetuated cycles of trauma and reinforced barriers to care. Substance use services that were women-led, safe, and responsive to women’s needs were valued and sought after. Conclusion: Women reported a cycle of trauma and drug use exacerbated by oppression in substance use services settings. In addition to increasing access to gender-responsive care, our study highlights the need for greater research and examination of practices within addiction treatment settings that may be contributing to gender-based violence.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade in the United States, women have accounted for an increasing proportion of individuals initiating drug use and those with substance use disorders (SUD) (Han et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2015). Research demonstrates that women experience disproportionate drug-related health harms and have greater unmet addiction treatment needs compared to men (Des Jarlais et al., 2012; Greenfield et al., 2007b; Harris et al., 2022). Rates of prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose deaths increased at a more than 2:1 rate in women compared to men between 1999 and 2017 (Jones et al., 2015; VanHouten, 2019). Given shifting epidemiologic trends and rising drug-related health harms among women, the field needs to understand how gender shapes drug use and addiction service experiences to inform effective addiction service and policy development (Keyes et al., 2008; Seedat et al., 2009).

Despite evidence demonstrating gender differences in access, experience, and effectiveness of SUD treatment, most substance use services (e.g. harm reduction programs, detoxification, residential treatment facilities, recovery support groups, and medication treatment services) have been designed and implemented using a gender-neutral approach (Iversen et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2019; Meyers et al., 2020). Such approaches benefit men over women as they fail to consider the impact of gender-related marginalization and women’s specific needs (Choi et al., 2021; Collins et al., 2019). For example, women experience greater economic disparities, have a higher burden of mental health and trauma, have more childcare responsibilities, and have different physical, sexual, and reproductive health needs compared to men (Harris et al., 2022). Despite women accounting for approximately one-third of people with SUD, only one-fifth of people in addiction treatment are women, highlighting a persistent treatment gap (United Nations, 2020). Designing programs that address women’s needs could mitigate such disparities (Greenfield & Grella, 2009). Though some women-specific substance use services are available, they tend to be concentrated in urban settings and/or primarily designed for pregnant or newly parenting women (Boyd et al., 2020; Niv & Hser, 2007). Other key services for women’s well-being, such as interpersonal violence services, mental health care, sexual and reproductive health care, and child care services, remain siloed from substance use services. (Harris et al., 2022).

The fragmentation of services is problematic given that experiences of physical and sexual violence and related trauma may be key drivers of drug related risks and barriers to substance use prevention and treatment among women (Boyd et al., 2018a; El-Bassel et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2021). Intersectionality is a critical theoretical framework that draws attention to how systems of power and privilege impact those with multiple stigmatized identities (e.g., female gender) and practices (e.g., drug use, sex work) (Bowleg, 2008, 2012; Crenshaw, 2013). For example, related to the criminalization of and stigma associated with sex work, engaging in sex work exacerbates gender-based violence and drug related harms among women who use drugs (Beattie et al., 2015; El-Bassel et al., 2020; Goldenberg et al., 2020). Ethnographic studies on harm reduction services find that such settings can offer refuge from physical and sexual violence (Boyd et al., 2018a; Fairbairn et al., 2008). However, many harm reduction spaces remain male-dominated thereby reproducing societal gender-power imbalances (Bonny-Noach & Toys, 2018; Boyd et al., 2018b), and few studies have explored gendered experiences in other substance use service settings. Applying an intersectional lens is thus essential to understanding how multiple axes of discrimination related to social identities (e.g., female gender) and practices (e.g., drug use and sex work) intersect and influence what it means to be a woman who uses drugs in a particular social and cultural context (Kulesza et al., 2016; Logie et al., 2021; Shields, 2008).

Therefore, grounded in the theory of intersectionality, we conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative interviews among self-identified women using non-prescribed opioids to understand women’s needs around drug use and substance use treatment. We examined how the axes of gender identity and drug use and sex work practices intersected and related to: (1) drug use experiences, (2) experiences with substance use services, and (3) preferences for substances use services. Findings from this work may help inform the development of future gender-responsive substance use treatment services and drug policy.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and setting

We conducted a secondary analysis of a two-site, mixed-methods study of self-identified women. The primary study aimed to (1) assess the acceptability of research recruitment strategies and (2) describe experiences with and preferences for research and drug use service engagement among women actively using non-prescribed opioids. Interviews also explored drug use experiences. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (19–29181) and the Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board (H-39303) reviewed and approved the study.

2.2. Recruitment

Research staff in Boston and San Francisco recruited individuals who met the following criteria: identified as women, English-speaking, aged 18–65, and reported non-prescribed opioid use in the past 14 days. Previous research showed age as an important factor in women’s research participation and drug use experiences, thus we intended to recruit 15 individuals under age 30. The study included three planned recruitment strategies: collaboration with a community partners, social media, and respondent driven sampling (Gelinas et al., 2017; Heckathorn, 1997; M. Jones et al., 2022). Approximately two months after study recruitment began in January 2020, the emergence of COVID-19 restricted in-person recruitment approaches. In response, research staff at both sites implemented a 4th recruitment strategy, “passive recruitment” defined below. Recruitment ended in October 2020.

In Boston, we identified a community-based partner that serves people who use drugs and the study supported 0.20 FTE of an outreach worker’s salary to support recruitment efforts. In San Francisco, a dedicated recruitment manager, with extensive community enrollment expertise, received part-time salary support to lead recruitment efforts at community-based organizations including syringe services programs, shelters, and health centers tailored for people who use drugs. Social media recruitment involved tailored ad campaigns on Facebook and Instagram featuring women of diverse racial identities and explicit reference to opioid use. As part of the respondent-driven sampling approach, the study invited participants to complete a training on study goals and peer recruitment strategies and were provided with coupons to distribute to potential participants. Women who completed the 30-minute recruitment training to implement respondent-driven sampling received an additional $50 of compensation. Passive recruitment involved posting flyers at organizations that work with people experiencing homelessness, youth, transgender individuals, and people who use drugs, including health care centers, syringe service programs, shelters, and social service programs.

2.3. Qualitative interviews and questionnaire

The study team, including two addiction medicine clinicians and a qualitative health services researcher, developed a flexible interview guide and brief demographic questionnaire. Interview guides were tested prior to study initiation by two research staff. Following informed consent, research staff invited participants to participate in individual 45–60 minute in-person or telephone interviews. Trained research staff (AML, VMM, CB, all identifying as women) completed interviews between January–November 2020. A brief questionnaire collected demographic characteristics, highest level of education, caregiving role, housing status, past 30-day drug use, preferred drugs and routes of administration, and past 30-day overdose data. Interviews explored: (1) experiences with drug use and social services and health care related to being a woman; (2) experiences of recruitment for the current study; and (3) experiences in other research studies. Study staff conducted seventeen interviews in person and 19 virtually or by phone. This analysis specifically focused on the first domain. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were compensated $40 for their time.

2.4. Analysis

Research staff imported de-identified transcripts into NVivo qualitative data management software version 12.1 (NVivo, 2012) for analysis. The lead author (MTHH) developed a codebook (Appendix 1) comprised of concepts represented in an intersectionality framework that focused on the axes of gender identity and sex work, and their relationship to drug use and health and social service experiences (Crenshaw, 2013; Logie et al., 2011). The codebook was tested on two transcripts and amended to clarify concepts and incorporate emergent, inductive themes not represented in the conceptual model (Ando et al., 2014). Two coders (combination pairs of MTHH, JL, and EH) independently coded six transcripts and came together to assess agreement, with discrepancies resolved through a group consensus process (Burla et al., 2008). The remaining transcripts were independently coded, and the coding team met to review and resolve any coding uncertainties regularly. We used grounded content analysis to identify themes related to the intersectional framework and inductive emergent themes related to drug use and service experiences (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Pseudonyms are used throughout the article to protect participant confidentiality.

3. Results

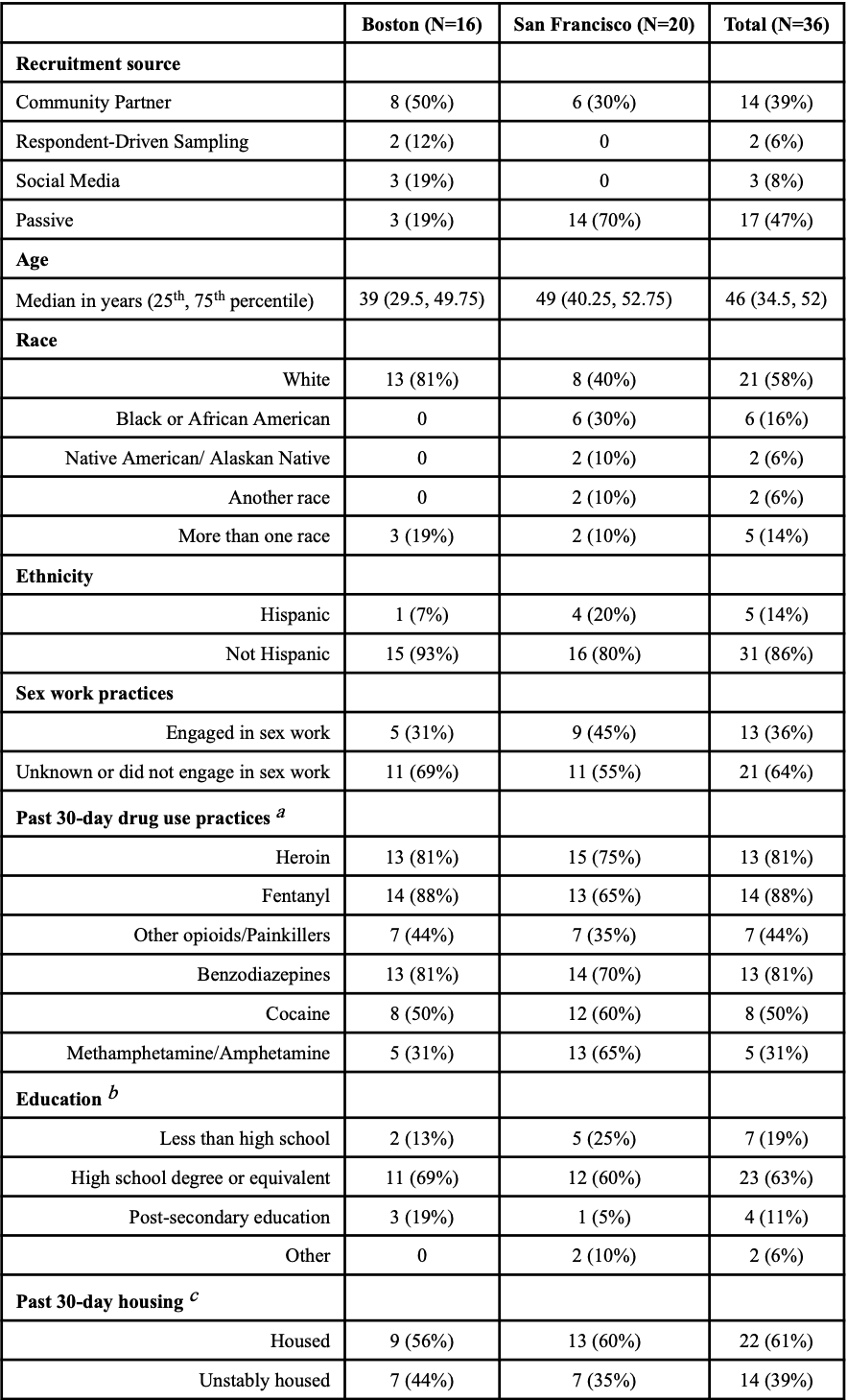

A total of 36 participants completed interviews, 16 in Boston and 20 in San Francisco. Seventeen participants were recruited prior to COVID-19 and related study activity changes and 19 were recruited after. Table 1 displays recruitment sources and participant characteristics. Most (31, 86%) participants were recruited through community partnership and passive community outreach strategies. The median age was 46 years; 58% were White, 14% were Hispanic, and 39% were unstably housed. Though we did not ask about sex work practices a priori, most women talked about sex work and 13 women reported engaging in sex work. Neither gender identity nor sexual orientation data were collected a priori and though none of the participants discussed experiences related to being trans- or queer-gender several participants identified as gay, lesbian, and/or bisexual. Multiple substance use was common among participants with more than half reporting heroin, fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and/or cocaine in the past 30 days. Methamphetamine use was also common and varied by region where 65% reported use in San Francisco and 31% reported use in Boston.

Table 1. Participant Demographics and Characteristics of Self-Identified Women with Opioid Use from San Francisco and Boston, 2020

a. Participants could respond yes vs no to multiple substances, thus drug use practices add up to more than 100%.

B. Post secondary education included associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, and master’s degree.

c. Participants were asked where they slept most of the time in the past 30 days. Responses of car, bus, truck, or other vehicle, abandoned building, shelter, or on the streets were considered unstably housed; all other response e.g. living in an apartment or SRO were considered housed.

Though the study predominantly recruited women from urban sites in Boston and San Francisco, women shared diverse life experiences spanning many years and locations. For example, women discussed drug use and service experiences from their youth and from other cities or states. From these diverse experiences and the content analysis, we distilled four themes related to the intersection of gender identity and drug use and sex work practices, and their impact on drug use and substance use care experiences.

3.1. The intersection of gender identity and drug use and sex work practices magnified experiences of oppression among women.

Women described how drug use practices intersected with gender-related oppression, compounding experiences of marginalization and exacerbating power imbalances between men and women. Women related such power imbalances to the fact that drug use environments, economies, and social relationships were controlled by men.

“It’s just hard, period. I mean, it’s like imagine a woman that doesn’t do drugs getting through the world, right? You take stuff like that, and you add a million on top of that, and that’s what it’s like [for women who use drugs]. I mean, most of the dope dealers are men…If you let them, [the men] will walk all over you.” (Darlene, <30-years-old, San Francisco)

A lack of safety while using drugs was a primary concern and was sometimes related to practical physical differences between men and women, as Deena (<30-years-old, Boston) described, “I mean, well obviously, we’re smaller, weaker, easier to get robbed, mugged, played, whatever from whoever...If you’re strung out and female, they will take advantage of you.” Participants described physical and sexual violence as ubiquitous in drug use environments, summarized by Sylvia (<30-years-old, San Francisco) “every single one out here, we have all been sexually assaulted”. Women attributed greater marginalization and violence to the intersection of female gender identity with drug use practices and assumed or intentional/coerced sex work practices.

“It’s almost like [the men] can smell the new females…And they get them and go take them somewhere, and start getting high, and the girl ends up passing out. And they wake up, and they don’t have nothing, and they’ve been raped, and all kinds of other things.” (Darlene, ≥ 30-years-old, San Francisco)

“As my addiction progressed, I turned to prostitution. I was on the street. I was actually held hostage by a drug dealer. You’re just an object that someone used to make a profit. feel like I’m a human statistic and stigmatized.” (Tamera, ≥30-year-old, Boston):

Women felt that the criminalization of drug use exacerbated gender-based violence. Criminalization and policing made women more, rather than less, vulnerable to violence because perpetrators knew women who used drugs would be less likely to seek help or report an assault.

“Anytime you’re high and you’re in a vulnerable state that makes it easy for someone to target you. The fact that you’re doing something that’s illegal and are less likely to want to go to the police, that makes you an ideal target.” (Sophia, <30-years-old, Boston)

Repeated experiences of intimate partner violence or street-based violence during drug use or sex work resulted in trauma that perpetuated a cycle of drug use and lack of empowerment for some women. Other women felt this cycle impacted their mental health and ability to cope with adverse experiences.

“They do whatever they want to you. It’s degrading and it’s so hard to get out of that. You remember what it’s like. And the drugs intensify it…You don’t want to stay sober because of that, you don’t want to remember.” (Sylvia, <30-yrs-old, San Francisco)

“It’s much deeper than just being hit. I meet a lot of these younger girls, and I can just see it. It’s plain as day. And the only reason I see it is because it’s in me, too... After [seeing a new woman] walk away, I’ll tell my girlfriend, “How long do you give her?” And she’ll be like, “I give that one two weeks.” [Two weeks] Until she’s totally broken down…When you first meet the girls, they’re clean. They look healthy…Broken down is when you see them again, they ain’t got no shoes on. They’re filthy. They weigh about two pounds, soaking wet. They’re either being ran around by some dude, or they’re talking to themselves, they’re lost...It’s an ugly dark thing...It gets your mind all twisted up.” (Rhonda, ≥30-years-old, San Francisco)

The intersection of gender, drug use, and sex work compounded experiences of oppression and physical and sexual violence against women. Criminal and legal structures exacerbated women’s vulnerability and diminished their ability to protect themselves.

3.2. Women perceived that substance use services favored men socially and structurally.

All women in our study accessed some form of substance use or health service supports, such as methadone treatment, detoxification facilities, residential treatment, office-based addiction treatment, harm reduction programs, and/or shelter or housing services (herein referred to as substance use services). Women shared experiences that spanned their life and from different cities and states. When trying to access services women felt less prioritized compared to men.

“I feel like I’m not looked at as serious as a man would be…It’s like, she’s a woman. We’ll give her help, but she’ll wait. She’s not a top priority. She’s second…that’s putting it in a nutshell, that’s just what I observe…from what I see on the streets and from what I hear on the streets, it’s not just me.” (Terry, ≥30-years-old, San Francisco)

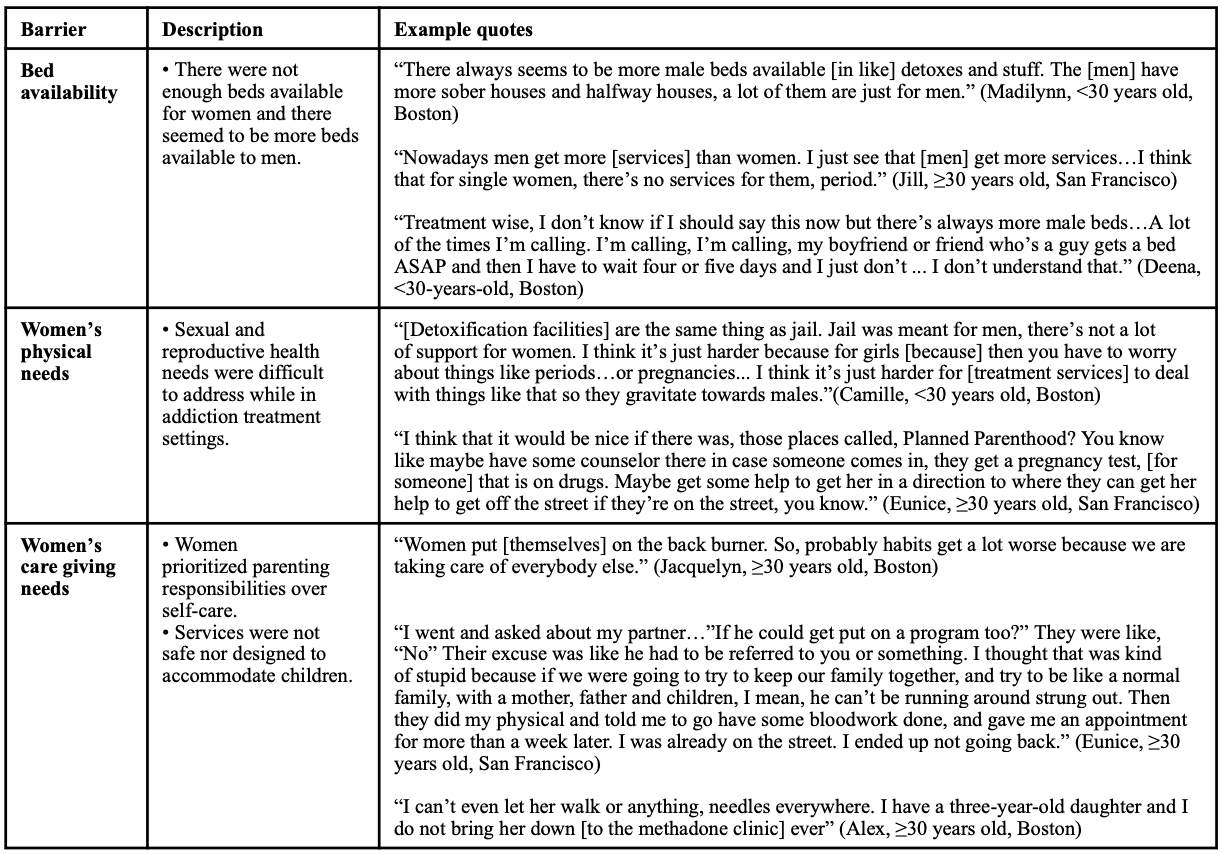

Women reported that substance use services structurally favored men in terms of access and design. Table 2 summarizes some of the gender-specific barriers reported by women, which included unmet sexual and reproductive health needs, lack of childcare, and inadequate bed availability.

Table 2. Gender-specific barriers to substance use services: example quotes selected from thirty-six qualitative interviews among women with opioid use from San Francisco and Boston, 2020.

Overall, though all women engaged with substance use services, the experiences of gender-related structural barriers to care, such as a lack of bed availability and childcare services, made it harder to access and engage.

3.3. Gender-based violence occurred in substance use service settings and perpetuated cycles of trauma.

Women felt that substance use services were male-dominated spaces. Half of the women in our study also described experiences of assault within substance use services that were attributed to their gender identities and assumed or intentional/coerced sex work practices. For example, peer assault was permissive in peer-recovery settings.

“There was a high, very high risk, even in recovery, of sexual assault… [In recovery meetings] older men or women with a lot of time under their belt, who sort of present themselves as a mentor…and prey on the younger, less sober folks. Their intention was to simply ... to use you, to get you in a position where you trust them enough where they can try to make a move on you physically in a sexual manner.” (Lilianna, <30-years-old, Boston)

Women also witnessed and experienced sexual assaults in harm reduction programs, at times perpetrated by staff. While Sophia (<30-years-old, Boston) related an experience of assault from a physician at a harm reduction program, she emphasized “when I say that people are likely to target you, I’m not talking about drug dealers. I’m talking about doctors. People are who just like, ‘Oh, nobody’s going to believe her. She’s just some druggy.’ The people that I’ve had the most problems with are not other individuals who use drugs, it’s largely been medical professionals.” Such experiences of assault caused further traumatization and barriers to care.

“I know a lot of females that have doctors proposition them because they think that because you do dope, you’re automatically a prostitute…it’s still even hard for me to go to the doctor. I think my wife feels like this, my daughter does, too…I even know a couple of females that took them up on the offer because they thought, “Oh, doctor, okay. Lots of money” (Darlene, ≥30-years-old, San Francisco)

“I’ve talked to a few girls that think that kind of environment [a recovery high-school where abuse occurred] was good for them, and others who kind of had the same experience as me where they feel like it was just totally traumatizing and that they just came out worse as a result of it.” Abigail (<30-years-old, Boston)

In summary, women reported persistent gender-based violence and fear of violence in substance use service settings, and these experiences created more trauma and barriers to care.

3.4. Substance use services that were safe and responsive to women’s specific needs were valued and desired by women.

Women described resilience and empowerment related to identifying as a woman. Some women derived strength from parenting and other strong social connections or obligations. As Rhonda (≥30-years-old, San Francisco) explained, “as women, we’re already nurturers, we’re really the strong backbone of the family and the family inspired them to seek help and addiction treatment”. Similarly, women took care of each other in drug use environments.

“Everybody looked out for each other. If somebody was sick, we wouldn’t leave our friend sick. If we have money, we’re not making somebody go have sex or do something they don’t want to do to get high. We’re going to help them” (Alex, ≥30-years-old, Boston)

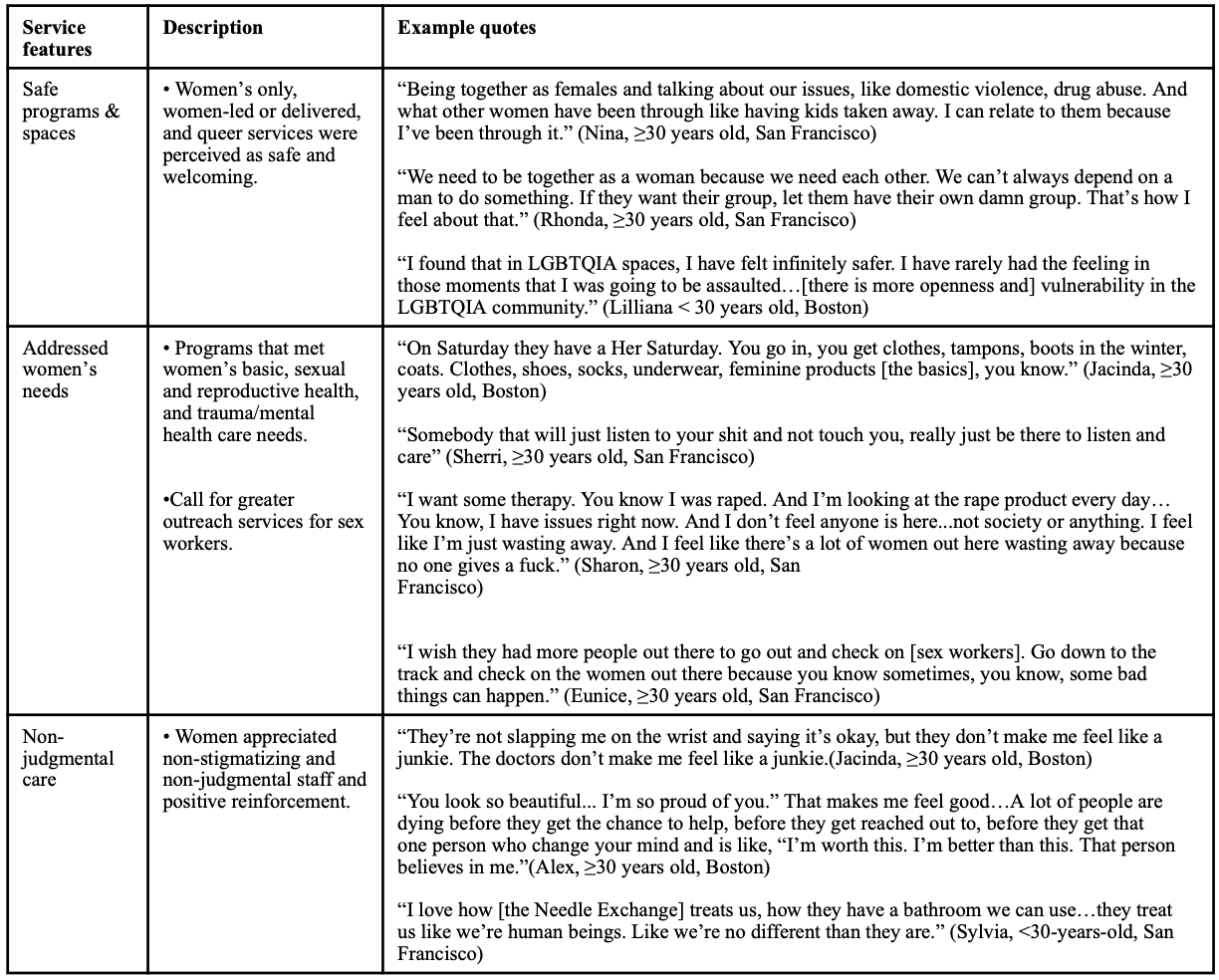

Women sought substance use services that facilitated female empowerment and addressed their specific needs. Table 3 summarizes some features of programs that women valued and/or desired. Women valued programs in which they felt safe, such as women-led or women’s only services or services tailored to LGTBQIA/queer individuals. Women also valued services that addressed their specific needs, including offering tampons, socks, underwear, and hygiene products. Programs that incorporated trauma-informed approaches were also key for women staying engaged with services. Women discussed the importance of staff having skills to support them during times of crisis, for example when they were feeling over intoxicated or having a manic episode. Some participants called for greater street outreach efforts to protect women engaged in sex work given their heightened risks of violence. Last, women appreciated programs that offered non-judgmental care and offered positive reinforcement throughout their substance use and treatment journeys.

Table 3. Features of substance use services preferred by women: example quotes selected from thirty-six in-depth interviews among women with opioid use from San Francisco and Boston, 2020.

Overall, women sought to engage with services that were safe, addressed their female-specific needs, facilitated connections between women, and were judgment-free. In general, women felt more outreach and gender responsive services were needed.

4. Discussion

This qualitative study among 36 women reporting recent non-prescribed opioid use in San Francisco and Boston identified several important findings. Interviews revealed that intersectional positions across multiple axes of discrimination including being a woman, engaging in drug use, and practicing sex work, exacerbated experiences of marginalization. Physical, sexual, and psychological violence were ubiquitous in drug use environments, and women attributed violence to the intersection of gender identity and drug use and sex work practices. Some women reported experiences of gender-based violence when engaging with substance use services, including violence committed by service providers. Such experiences perpetuated cycles of trauma and exacerbated barriers to care. Participants perceived substance use services that facilitated connections between women and addressed women’s specific needs as safe, valued, and sought after.

Our findings highlight the complex interaction of intersectional identities and practices resulting in experiences of marginalization among women who use drugs. Policies and systems exacerbated oppression, especially among women who practiced sex work. Women in this study noted that the criminalization of drug use and sex work intensified gender-based violence. The use of illegal drugs increased women’s vulnerability because assaulters knew that women would be less like to seek and/or receive help from the criminal-legal system. Our findings build on other studies that similarly show the deleterious consequences of drug use and sex work criminalization. Ethnographic data from cis-and transgender women sex workers in Vancouver, Canada showed that policing increased rather than decreased their vulnerability to violence (Krüsi et al., 2014). Among a cohort of sex workers also from Vancouver, most of whom used drugs, punitive policing practices were associated with increased odds of overdose and reduced odds of substance use treatment access (Goldenberg et al., 2020; Goldenberg et al., 2022). Our findings strengthen calls for decriminalization of drug use and sex work along with policies and interventions that strengthen trauma-informed substance use services. (Goldenberg, 2020; Shannon et al., 2008).

Our study highlights the need for more research that examines experiences of violence within substance use service settings. Half of participants reported experiences of sexual or physical assault when accessing substance use services. Assaults were perpetrated by other people using the services, but also by health and social service professionals delivering care. Such experiences of assaults caused further traumatization and exacerbated barriers to care for women in our study. Though evidence exists showing gender-based violence is common and a significant factor in increasing drug use harms and reducing access to substance use services for women who use drugs (Deering et al., 2021; El-Bassel et al., 2020; Lorvick et al., 2014), few studies have focused on violence occurring within these settings and the potential impact on treatment access and effectiveness. In addition to research, substance use services must examine policies, procedures, and cultures that may be contributing to violence against women and/or underreporting of assaults.

Women felt substance use services de-prioritized them and believed that services socially and structurally favored men in terms of access and design. Specifically, women noted that substance use services did not address women’s sexual and reproductive health and childcare needs. Such experiences are consistent with studies that show the persistent barriers to treatment among women and treatment service gaps between men and women (Aggarwal et al., 2021; Ayon et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2021). In keeping with past studies, women valued substance use services that facilitated empowerment and safety (Boyd et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2019). Participants perceived women’s only and LGTBQIA spaces as safe and welcoming. Women appreciated programs that were trauma-responsive and offered sexual and reproductive health services. Research shows that gender-responsive SUD treatment, treatment that is tailored to address the specific needs of women, improves SUD outcomes such as treatment access and retention (Greenfield et al., 2007a; Niv & Hser, 2007). Previous work also shows that women-only and sex work specific service utilization increases linkage to other addiction and sexual and reproductive healthcare for women who use drugs (Ayon et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015). Thus, our work strengthens calls for the development, implementation, and investment in gender-responsive substance use services. Such efforts should include the integration of women who use drugs within the substance use care-related work force based on the reported value of peer-support in our study and evidence that peer-delivered services increase engagement with care (Collins et al., 2019; Deering et al., 2011).

Our findings must be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. The study sample and approach mitigated exploring the impact of key racial and ethnic intersectional identities. Additionally, our study focused explicitly on female gender identity, and we did not collect nor explore diverse gender or sexual orientation identities and their intersectional impact on experiences. Thus, the value of women-only and sexual reproductive health services reported by our participants may be overstated and/or lacking nuance. More qualitative and quantitative research should seek to better understand the impact of multiple intersecting identities on drug use and substance use service experiences to inform establishing inclusive and responsive approaches. Young women were also under-represented in our study. Other studies suggest young women may experience more violence and greater barriers to care, therefore more research focused on youth experiences are needed (Chettiar et al., 2010; Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016). COVID-19 forced changes in recruitment and interview procedures during the study. Those recruited after the emergence of COVID-19 may have been different from the women recruited before and thus our findings may have been impacted by COVID-19, but this was not systematically assessed. Last, the study recruited participants from two geographic locations, and our data provides a snapshot of experiences that may be less generalizable to other settings.

5. Conclusion

Women described repeated experiences of marginalization when accessing substance use services that exacerbated a cycle of trauma and drug use. In addition to increasing gender-responsive services that integrate trauma-informed models of care, our study highlights the need for research that examines experiences of violence within substance use service settings. Participants spoke out about program cultures and policies that made it unsafe for them to seek needed care. The SUD treatment community should also investigate and address its own practices that may be contributing gender-based violence and the re-traumatization of women accessing care.