Abstract

Background: The prevalence of HIV and substance use (SU) disorder is significantly higher among individuals involved in the criminal legal system than in the US generally (HIV: 1.2% vs 0.013%) (SUD: 65% vs 16.1%). Young adults (YA) are disproportionately represented in rates of incarceration, HIV, and SU disorder. Despite the high need, there are few successful interventions that link criminal legal involved (CLI) individuals to SU and HIV services, and even fewer tailored to the needs of YA. Studies have shown that YA have lower engagement and retention rates in reentry programming, but causal factors have not been identified. The purpose of this study is to identify barriers to engaging CLI-YA in HIV and SU services. Methods: Key informant interviews were conducted with systems partners (n=8) from the criminal legal (n=3) and public health sectors (n=5). Systems partners were asked about: 1) experiences linking CLI-YA to HIV and SU services; 2) perspectives on a navigator intervention for use with CLI-YA; 3) perspectives on how a navigator intervention could be adapted in the context of the study setting. Interviews were analyzed via Inductive Thematic Analysis. Analyses were facilitated via Dedoose. Results: Four themes impacting HIV and SU service engagement for CLI-YA were identified: 1) the health and social services landscape; 2) life chaos; 3) relationships and social support; 4) readiness to change and engage in services. Structural factors were associated with the health and social service landscape (e.g., accessibility of services) and life chaos (e.g., competing needs), social factors with relationships and social support (e.g., provider relationships), and individual factors with readiness to change and engage in services (e.g. risk perception). Conclusions: Improving rates of HIV and SU service engagement for CLI-YA would require an approach that addresses structural, social, and individual level factors. Instituting a collaborative jail discharge process that includes jail staff, service providers, and CLI-YA could help address structural barriers to SU and HIV service engagement. Developing HIV and SU programs that include peers, build non-judgmental provider-patient relationships, prioritize autonomy, and employ principles of harm reduction could address social and individual level barriers to program engagement for CLI-YA.

1.0 Introduction

In the United States (US), over 5.5 million people are controlled by the criminal legal system (CLS) either through incarceration in prison or jail, or by community supervision through probation or parole (Sawyer & Wagner, 2023). The prevalence of both HIV and substance use disorder (SUD) is significantly higher among individuals incarcerated in prisons than in the US population as a whole (HIV: 1.2% vs 0.013%) (SUD: 65% vs 16.1%) (Dailey et al., 2020) (Maruschak, 2022; NIDA, 2020; SAMSHA, 2022). There is the potential for detention settings to serve as an avenue for people to be engaged in HIV and substance use related services, but unfortunately, upon release people living with HIV often experience lower rates of antiretroviral treatment adherence and retention in care than their counterparts who have never been incarcerated (Iroh, Mayo, & Nijhawan, 2015). Additionally, following release from detention the rate of fatal overdose is >20 times higher than that of the general population (Hartung, McCracken, Nguyen, Kempany, & Waddell, 2023). Despite this, rates of SU treatment provision in jails and prisons is low (Widra, 2024).

Young adults (YA), 18 to 34 years old, represent 41.9% of incarcerated adults in the United States (Ann Carson, 2022). YA aged 13-34 account for 57% of new HIV infections nationally (Dailey et al., 2020). YA also disproportionately experience SUD, with 25.6% of those 18 to 25 estimated to meet the criteria for SUD (as of 2021), compared to 16.1% of those over the age of 26 (SAMSHA, 2022). Factors that may account for increased rates of CLI, SUD, and HIV incidence among young adults include an imbalance of brain maturity through the second decade of life, increased peer influence on behaviors, identity exploration, and life instability (SAMSHA, 2019; Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021).

Despite their unique needs and developing brain maturity, YA are not considered their own group by the CLS, and therefore do not receive YA specific programming (Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021). Identifying the barriers to care and other challenges that YA with SUD who are living with, or at risk for developing, HIV face when returning to their communities from jail can aid in developing future interventions aimed at improving care linkage and retention uniquely tailored to this population.

1.1 Specific Aims

The specific aims of this study are:

I. To identify barriers to engaging criminal legal involved 18–29-year-olds in HIV related services.

II. To classify barriers to engaging criminal legal involved 18–29-year-olds in substance use services.

1.2 Hypothesis

The hypothesis of this study is that service providers will report that young adults (18-29 years old) who have been involved with the criminal legal system face more barriers to engagement in HIV and substance use services in the community than their older counterparts (>29 years old).

2.0 Review of the Literature

2.1 Criminal Legal System Overview

The United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world (Widra & Herring, 2021). Over 5.5 million individuals are under control of the criminal legal system, either through confinement in jail or prison, or through community supervision (probation and parole) (Sawyer & Wagner, 2023). The criminal legal system disproportionately impacts people of color, particularly those who are Black or Latinx. Black individuals have an incarceration rate more than 5 times that of their White counterparts, and Latinx individuals have an incarceration rate 1.3 times that of White individuals (Nellis, 2021). This disparity in incarceration rates is driven by institutional and social racism, resulting in the over-policing of communities of color and destabilization of their communities (Hinton & Cook, 2021).

Even when local crime rates are controlled for, predominantly Black neighborhoods experience higher levels of police activity than predominantly White neighborhoods (Smyton, 2020) and Black youth are more likely to be stopped by the police than White youth, even when not engaging in criminalized activities (Harris, Ash, & Fagan, 2020). Further evidence can be found in disparities in arrests and sentencing. Black Americans are 3.5 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than White Americans, despite similar rates of use (ACLU, 2020) they receive, on average, longer sentences than their white counterparts, and they are more likely to receive the death penalty (Spohn, 2017).

In addition to the impact on communities of color, the CLS has significant consequences for individuals with mental health needs (Sugie & Turney, 2017). Following the deinstitutionalization of the mental health system, the CLS became a catch-all solution for the individuals with serious mental illnesses (SMI) (Lamb & Weinberger, 2014). It has been documented that 25% of individuals with CLI have SMIs (Lamb & Weinberger, 2014) and that the presence of a SMI is correlated with an increased likelihood of repeated arrests (Jones & Sawyer, 2019). It is also estimated that 65% of individuals in the United States prison system has substance use disorder (SUD) (NIDA, 2020). Contact with the criminal legal system consistently results in worse health outcomes across the board, particularly for individuals with existing mental health needs, including SUD (Hartung et al., 2023; Klein & Lima, 2021; Sugie & Turney, 2017).

Drug use has been heavily criminalized since the initiation of the War on Drugs by President Nixon in 1971 (Hodge & Dholakia, 2021). The number of incarcerated people in the United States rose from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 in 1997 (Hodge & Dholakia, 2021). The results of this policy are widespread and can still be seen today. Currently, one in five people who are incarcerated are in jail or prison because of a drug offense (Sawyer & Wagner, 2023). The War on Drugs disproportionately impacted people of color, which can be seen in disparities in arrests related to marijuana use for Black Americans, despite similar rates of use to White Americans (ACLU, 2020). The high rates of SUD among incarcerated people in the United States can be partially attributed to policies and laws criminalizing drug use and possession resulting from the War on Drugs.

2.2 Syndemics of HIV Substance Use and the Criminal Legal System

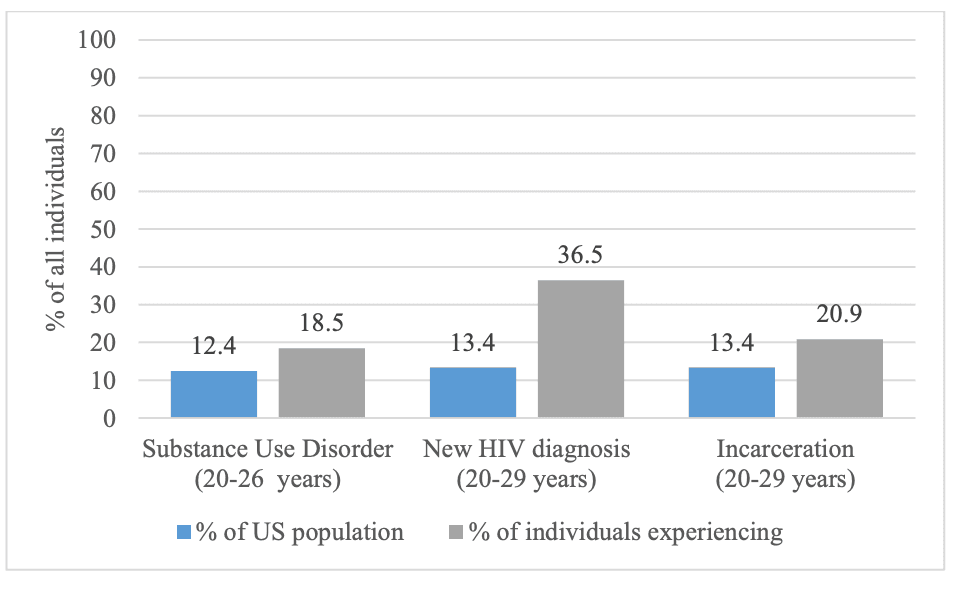

The criminalization of marginalized groups (e.g., Black Americans, sex workers, people who use drugs) has contributed to the disproportionate representation of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the CLS. As of 2020 the prevalence of HIV for incarcerated individuals in the United States was 1.2%, which is 3.7 times higher than the overall US prevalence of 0.32% (Dailey et al., 2020; Maruschak, 2022). This disparity could be attributed to higher rates of both structural and individual level HIV risk factors experienced by incarcerated people including healthcare access, racism, substance use (SU), and sexual risk taking (Marotta et al., 2021; Maruschak, Bronson, & Alper, 2021; SAMSHA, 2022). Additionally, many factors that influence HIV risk (e.g. substance use, sex work, race) also increase the likelihood that an individual will come into contact with the CLS (Hinton & Cook, 2021; Zgoba, Reeves, Tamburello, & Debilio, 2020). Young adults (YA) specifically, are disproportionately represented in HIV incidence, estimated substance use disorder (SUD) prevalence, and incarceration rates ("Age and Sex Composition: 2020," 2020; Ann Carson, 2022; Dailey et al., 2020; SAMSHA, 2022). The definition of ‘young adult’ varies by reporting agency, making it challenging to draw direct comparisons across groups and settings. However, by comparing the percentage of individuals in each group (e.g. estimated to have SUD, newly diagnosed with HIV, currently incarcerated) who are YA (as defined by the reporting agency) with the percentage of the total US population who are YA (as defined by the reporting agency) it becomes clear that YA are overrepresented on all fronts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of individuals estimated to have SUD, newly diagnosed with HIV, or currently incarcerated that are young adults as compared to the percentage of the total US population that are young adults ("Age and Sex Composition: 2020," 2020; Ann Carson, 2022; Dailey et al., 2020; SAMSHA, 2022)

Much work has been done that is focused on linkage to prevention and treatment services for individuals with CLI. However, the transition period from incarceration back into the community is marked by unique challenges related to care (Pulitzer, Box, Hansen, Tiruneh, & Nijhawan, 2021). After release from detention facilities the fatal overdose rate is >20 times higher than that of the US population as a whole (Hartung et al., 2023). Additionally, PLWH often have lower levels of viral suppression and ART adherence than they did prior to being incarcerated (Iroh et al., 2015). Incarceration disrupts every part of an individual’s life, from medical care to the maintenance of housing and social supports. This disruption makes it difficult for an already vulnerable population to get, and stay, engaged in care, especially without a comprehensive care plan in place prior to release (Springer et al., 2011).

Given the disproportionately high rates of, and poor outcomes associated with, HIV and SUD among CLI-YA, it is important to consider how these factors may influence, or even amplify, each other. It has been well documented that SU increases the likelihood of individuals to participate in sexual behaviors that increase their likelihood for HIV acquisition (Levy, Sherritt, Gabrielli, Shrier, & Knight, 2009; Mateu-Gelabert, Guarino, Jessell, & Teper, 2015; Vosburgh, Mansergh, Sullivan, & Purcell, 2012). This has implications for HIV spread regardless of someone's status. PLWH who are using substances may be more likely to transmit HIV to their partners, particularly if they are not virally suppressed, and people who use drugs (PWUD) who do not have HIV may be more likely to contract it from someone else. Additionally, CLI has been shown to be associated with increased rates of sexual behaviors that increase likelihood for HIV acquisition (Knittel, Snow, Griffith, & Morenoff, 2013; Marotta et al., 2021), lower rates of viral suppression in PLWH (Ickowicz et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019), and higher rates of SUD when compared to the general population (Maruschak et al., 2021).

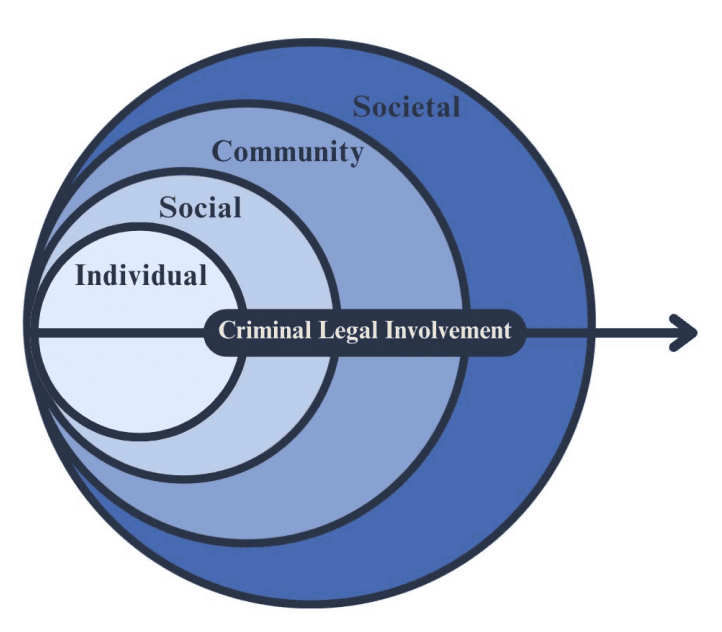

To gain an in depth understanding of the intersection of HIV, SU, CLI it is helpful to contextualize it within the socioecological model (SEM) (Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2013), and to look beyond individual risk factors, considering how incarceration itself acts as a social determinant of health. Incarceration has been well documented to have major mental and physical health impacts, including elevating rates of SUD and other mental health outcomes, increased rates of communicable diseases, and increased overall mortality (Klein & Lima, 2021). One systematic review and meta-analysis found that recent incarceration was associated with an 81% increase in HIV acquisition risk (Stone et al., 2018). While the direct mechanism of association between incarceration and poor health outcomes has not been definitively identified, it is known that incarceration causes widespread disruptions across the SEM that are directly related to traditional social determinants of health such as healthcare access, housing, employment, social support, and stigma (Figure 2) (Zaller & Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2018).

Figure 2: Socioecological model of criminal-legal involvement (Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2013)

One example of this at the societal level is the direct impact that incarceration has on medical insurance access. When incarcerated, individuals lose their government sponsored health insurance. While they are eligible to have it reinstated upon release, this is dependent on their power to navigate the complicated social services landscape, and frequently results in periods of time where they do not have insurance at all (Springer, Spaulding, Meyer, & Altice, 2011; Zhao et al., 2023). Gaining employment is also a major obstacle following incarceration, which poses additional barriers to health insurance access in addition to the economic consequences (Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2013). Periods of being uninsured can seriously disrupt an individual’s engagement in HIV and substance use related services, directly impacting health outcomes across both categories.

An example that crosses individual and social levels of the SEM is stigma due to CLI. Stigma (enacted, perceived, anticipated, and internalized) associated with incarceration has wide reaching consequences for CLI individuals that both directly and indirectly impact their health (Feingold, 2021). A systematic review of the literature on stigma due to CLI found that stigma due to CLI was associated with increased SU, reduced SU treatment engagement, increased risky sexual behaviors, reduced social supports, and reduced overall wellbeing, among other factors (Feingold, 2021). The association of increased SU, reduced SU treatment engagement, and increased sexual behaviors that increase the likelihood for HIV acquisition with SU and HIV is clear, but strength of social support networks is also important to consider. Strong social support networks have been consistently correlated with better HIV (Atkinson, Nilsson Schönnesson, Williams, & Timpson, 2008; Kelly, Hartman, Graham, Kallen, & Giordano, 2014) and SU treatment outcomes (Rapier, McKernan, & Stauffer, 2019; Stevens, Jason, Ram, & Light, 2015). Given the syndemic nature of HIV, substance use, and CLI, it is imperative to consider how to address these issues together, as opposed to individually.

2.3 Jail Based Service Linkage

Individuals who have been incarcerated in jails as opposed to prisons, face unique challenges when returning to their communities. The average length of stay in jail in the United States is just 33 days (Zeng, 2022) which is significantly shorter than the average stay of 2.7 years for people incarcerated in United States prisons (Kaeble, 2021). Jails also experience, on average, a 41% turnover rate per week, with 70.9% of individuals in jail have not been convicted and are awaiting trial (Zeng, 2022). Additionally, many individuals are released from jail without notice, often late at night, without adequate discharge planning in place (Avery, Ciomica, Gierlach, & Machekano, 2019; Pauly, 2019).

The high turnover rate in jails makes identifying needs, adequately planning for discharge, and linking individuals to services challenging (Hicks, Comartin, & Kubiak, 2022). While needs (mental health, substance use, housing, etc) among the jail population are high (Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins, & Richie, 2005), actual rates of service linkage are often quite low (Allegheny County Disharge and Release (DRC) Data, 2024). Further challenges arise due to staffing issues, which have been exacerbated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Heffernan & Li, 2024). Even if there is as protocol for service linkage, without the proper staff to execute the protocol, effective service linkage cannot take place.

Some of the same factors that make jail-based service linkage challenging (e.g., high turnover rate) also make them an important potential point of contact for engaging members of systematically marginalized populations in care. More than 4.9 million Americans are booked into a jail each year, and one in four of them will be booked more than once in the same year (Jones & Sawyer, 2019). Rates of serious health needs (e.g. serious or moderate mental illness, serious psychological distress, SUD, lack of health insurance) are positively correlated with the number of times an individual has been arrested in the last year (Jones & Sawyer, 2019). Additionally, 81% of unhoused individuals report spending at least one night in jail in the past 6 months (Rountree, Hess, & Lyke, 2019). Unhoused people are often not engaged in care and experience higher levels of SUD, depression, HIV, and other health issues than people who are housed (Serchen, Hilden, & Beachy, 2024). Additionally, individuals with CLI are less likely to be engaged in primary and preventative care (Zhao et al., 2024), and more likely to be uninsured than those without CLI (Zhao et al., 2023). Given that jail currently acts as a safety net for of systematically marginalized individuals, and that those with serious health needs come into contact with the jail system most frequently, (Jones & Sawyer, 2019) they have the potential act as an important point of contact to engage, and re-engage, members of systematically marginalized populations in care.

This being said, it is important to remember the direct negative effects that incarceration has on health (physical and mental) and social outcomes for individuals with CLI (e.g., mental health, stigma, SU, mortality) (Klein & Lima, 2021). Though jails have the potential to act as a point of contact for linking people to services, they should not be considered a long-term solution to problems associated with healthcare access for systematically marginalized populations. However, as long as the CLS continues to disproportionately impact individuals who have high rates of health and social needs (Klein & Lima, 2021) it is important to consider how jails can be used as an access point to link people to care and improve outcomes.

2.4 Jail Based Integrated HIV and Substance Use Reentry Programming

Research on interventions to link CLI individuals to integrated HIV and SU services has been limited, particularly in jail settings (Grella et al., 2022). While the literature on HIV linkage after release from jail is fairly robust (Woznica et al., 2021), there are few studies that include SU service linkage in their protocol. Given the syndemic nature of SU and HIV, some studies primarily focused on HIV care linkage do include linkage to SU related services, but this is not often the primary outcome (Woznica et al., 2021). This can be at least partially attributed to differences in funding agencies and insurance payers for behavioral and physical health issues (Scott, Yellowlees, Becker, & Chen, 2023).

Of the seven interventions identified that were primarily focused on HIV care linkage with auxiliary SU service linkage, most initiated contact with participants in jail prior to release, and included discharge planning and comprehensive service linkage (Bishop, 2017; Booker et al., 2013; Cunningham et al., 2018; Myers et al., 2018). Peer navigators were included in four of the interventions identified (Bishop, 2017; Cunningham et al., 2018; Myers et al., 2018). Common factors in two of the peer navigator studies included psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and fostering social support and self-efficacy (Cunningham et al., 2018; Koester et al., 2014; Myers et al., 2018).

Rates of SU service linkage and SU related outcomes were reported in three of the seven studies (Bishop, 2017; Booker et al., 2013; Cunningham et al., 2018; Myers et al., 2018). The Booker et al. (2013) study reported only on rates of linkage to SUT. They linked 53.9% of participants to SUT services (Booker et al., 2013) In the Cunningham et al. (2018) study, they found that participants in the peer navigation group had increased rates of visits for medication for addiction treatment compared to participants who did not receive peer navigation. The Myers et al. (2018) study found no significant difference in alcohol and drug use behaviors between the intervention and control groups. Notably, they did find that individuals who received treatment for SUD in jail were four times more likely to be linked to care upon release than those who did not.

One study was identified that tested an a re-entry intervention for PLWH who had recently been released from jail who use substances (Hoff et al., 2023). The study by Hoff et al. (2023) was a randomized pilot trial that had formerly incarcerated community health workers connect PLWH to social, health, and re-entry agencies. Participants were contacted after release from jail and had an initial study visit within 60 days of release. They found that participants in the treatment group had lower rates of high-risk substance use, fewer positive urinary toxicology screens, increased readiness to change, and increased confidence in treatment. However, they found no difference in rates of HIV virologic suppression in the treatment vs control arms. The limited literature on integrated SU and HIV service linkage programs after release from jail, and the varied results in the trials that do exist, illustrates the need for further research on the subject.

2.5 Barriers and Facilitators to Service Engagement for Young Adults Post Jail Release

YA (18-29 years old) experience distinctive challenges related to HIV, SU, and the CLS. Their disproportionate representation in all three categories (Figure 1) ("Age and Sex Composition: 2020," 2020; Ann Carson, 2022; Dailey et al., 2020; SAMSHA, 2022) can be attributed to a variety of factors including an imbalance of brain maturity through the second decade of life, increased peer influence, identity exploration, and life instability (SAMSHA, 2019; Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021). These factors unique to YA illustrate the importance of considering YA as their own group with unique service needs. A one size fits all approach, as is current practice in the CLS (Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021), is not sufficient to address the barriers to service engagement unique to YA.

CLI-YA are more likely to engage in HIV risk behaviors (e.g. drug use, sexual risk taking) (Patrick, O’Malley, Johnston, Terry-McElrath, & Schulenberg, 2012) and less likely to be virally suppressed if they have HIV (Ludema, Wilson, Lally, van den Berg, & Fortenberry, 2020; Valera, Epperson, Daniels, Ramaswamy, & Freudenberg, 2009) than their older counterparts. Their risk of fatal overdose is also higher after release from detention than that of older adults (Selen Siringil Perker & LaelE. H. Chester, 2018). The above-mentioned factors (e.g. brain maturity, peer influence, identity exploration) contribute to high levels of risk taking behaviors among YA (Kelley, Schochet, & Landry, 2004).

CLI-YA also have different perceptions about, and patterns of, SU than their older counterparts. They are more likely to think their SU is not harmful (SAMSHA, 2019) and to use drugs with peers, as opposed to with family or community members (Sichel et al., 2022). Polysubstance use is also more common in CLI-YA than older adults, though CLI-YA are less likely to have opioid use disorder (Sichel et al., 2022). The unique behavior and belief profile of CLI-YA illustrates the need for programming that focuses on risk management and education specific to CLI-YA.

In addition to differences around HIV and SU, CLI-YA also experience lower rates of engagement and retention in reentry programs that older adults (Barnert et al., 2024). When evaluating program retention and participant needs for the Whole Person Care-LA Reentry program, researchers found that older age was associated with increased program retention after controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, history of being unhoused, and behavioral health diagnosis. Young adults (18-25 years old) also demonstrated unique needs profiles when compared to adults >25 years old. The researchers found that CLI-YA most frequently reported needs related to physical health, mental health, substance use, and primary care access (Barnert et al., 2024). This study is one of the first to describe: 1) reported needs; and 2) factors associated with intervention engagement specific to CLI-YA. While they did not identify specific factors that made CLI-YA less likely to engage in services, the fact that CLI-YA experienced lower retention rates even after controlling for other variables (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, history of being unhoused, and behavioral health diagnosis) suggests that there are factors specific to CLI-YA that influence program retention.

Despite their unique needs and developing brain maturity, YA are not considered their own group by the CLS, and therefore do not receive YA specific programming. Once someone turns 18-years-old and ages out of the juvenile system, they are subject to the same policies, procedures, and programs as older adults (Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021). Under the current system, CLIYA experience significantly higher rates of recidivism and of post release overdose than their older counterparts (Selen Siringil Perker & Lael E. H. Chester, 2018; William H. Pryor et al., 2017). Even when CLI-YA do receive SUT while incarcerated, their post release overdose rate is the same as CLI-YA who do not receive SUT (Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021). Additionally, multiple studies have found that CLI-YA living with HIV have lower rates of viral suppression than their older counterparts (Ickowicz et al., 2019; Takada et al., 2020). This is evidence that the current system is inadequate, and changes are needed to better meet the needs of CLI-YA. Further research needs to be done to identify the barriers and facilitators to service engagement specific to CLI-YA, especially given their disproportionately high rates of SUD and HIV incidence and lower rates of service engagement post-release.

3.0 Methods

3.1 Study Setting

This study took place in a mid-sized midatlantic city that has one adult jail within the city limits. Surveillance data from the study locale indicates that YA (20-29 years) account for 43% of all new HIV infections, with 65.8% of those diagnosed belonging to racial and ethnic minority populations (Portela, Mertz, & Wiesenfeld, 2020). Additionally, as of March 2024, 56% of those incarcerated in the county jail were between the ages of 18 and 34 years old and 66% of those incarcerated belonged to racial and ethnic minority groups ("County Jail Population Management Dashboards," 2024). Notably, from 2016-2020, 30% of individuals who died of an accidental overdose had been involved with adult probation and 19% had been booked in the county jail in the year preceding their death (Davis et al., 2021). The intersection of age, HIV, SU, and incarceration in this setting makes it a prime environment for this study. The demographic breakdowns of HIV and incarceration rates makes it generalizable to other, similarly sized, cities in the United States.

3.2 Key Informant Interviews

3.2.1 Data Source

Data for this project were collected as part of an ongoing three-year National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded project, mHealth Service Linkage for Justice-Involved Young Adults (Project LYNX) (mPI: Dauria; IRB: 22020053). Data were collected by members of the study team, one of whom is the author. Project LYNX is an R34 grant with the goal of developing and testing a program to link CLI-YA to HIV and SU related services. Data were collected during aim 1 of the project, intervention development, which included systems partner interviews. The goal of aim 1 was to collect data to inform intervention characteristics and recommendations for intervention implementation in the study setting.

3.2.2 Participants

Eligible participants worked in the criminal legal (CL), medical, or public health (PH) sectors. CL systems partners (n=3) were administrative or front-line staff at organizations that provide reentry supports to CLI-YA (including linkage to SU and HIV related services). Medical/PH systems partners (n=5) were administrative or front-line staff at that provide or link CLI-YA to HIV and/or SU related services.

3.2.3 Recruitment

Participants (n=8) were recruited from April 2023 to January 2024 via purposive sampling. Potential participants were identified through existing partnerships and active outreach to agencies that provide services to CLI-YA. After potential participants were identified, research study staff reached out via email to explain the project and schedule an interview. Following interviews, participants were compensated with a $50 gift card.

3.2.4 Data Collection

Interviews were semi-structured and guided by several domains from the Intersectionality Enhanced Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (IE-CFIR). The IE-CFIR is useful for identifying potential barriers and facilitators to intervention effectiveness (Keith, Crosson, O’Malley, Cromp, & Taylor, 2017). The IE-CFIR is organized into five domains based on context: 1) innovation; 2) outer setting; 3) inner setting; 4) individuals; 5) implementation ("Updated CFIR Constructs,"). Areas of inquiry included 1) experiences working with CLI-YA; 2) perspectives on a navigator intervention for use with CLI-YA; 3) perspectives on how a navigator intervention could be adapted in the context of the study setting (Table 1).

IE-CFIR Domain | Topic | Selected Questions |

|---|---|---|

Outer Setting | Experiences working with CLI-YA; Perspectives on how a navigator intervention could be adapted in the context of the study setting | What types of services do you find it challenging to refer the young adults you work with to? Probe: Lack of services? Lack of trusted services? YA willingness to engage? |

Individuals | Experiences working with CLI-YA | What are the biggest challenges to getting young adults that you work with to attend [court appointments/treatment]? Probes: Attendance? Engagement? General attitude? |

Innovation | Perspectives on a navigator intervention for use with CLI-YA; Perspectives on how a navigator intervention could be adapted in the context of the study setting | What would be important to consider when training the health navigator to work with criminal legal involved young adults? Probes: Diversity training? Familiarity with resources |

Table 1: Selected questions by IE-CFIR domain and topic from the key informant interview guide

Key informant interviews were conducted from April 2023 to January 2024. Prior to each interview, study staff sent a verbal consent document to each participant, the day of the interview study staff reviewed the document with participants and gained verbal consent. Interviews were 45-60 minutes in duration and led by study staff trained in qualitative data collection. All interviews were conducted via Zoom, recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Following interviews, study staff administered a brief questionnaire via RedCAP to collect sociodemographic information. A copy of the informed consent document can be found in Appendix A.

3.2.5 Data Management and Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim using TranscribeMe!’s HIPPA compliant transcription services. Following transcription audio recordings were destroyed as per the internal review board (IRB) protocol (reference: 22020053). Executive summaries of interview content were written within 48 hours of each interview. Executive summaries included descriptions of participant responses by content area, challenges with the interview process, suggestions for adapting future processes, and notes on whether data saturation was reached (Fusch & Ness, 2015). Transcriptions, executive summaries, and completed sociodemographic questionnaires were stored on secure servers (e.g., One Drive and RedCAP) accessible only to study staff.

Following transcription and completion of executive summaries, interview data was analyzed using Dedoose, a web based qualitative data management tool. Data was analyzed using Inductive Thematic Analysis (ITA) (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017). ITA is a data driven process where themes are generated from the data itself, as opposed to from prior theories and research (Boyatzis, 1998). The process of ITA involves six main steps: 1) familiarizing yourself with the data; 2) generating initial codes; 3) searching for themes; 4) reviewing the themes; 5) defining and naming themes; 6) producing the report (Nowell et al., 2017).

An initial codebook was developed based on the interview guide and transcripts. All transcripts were then coded line by line; the codebook was refined as necessary throughout the coding process. Following coding, initial themes were identified and codes were sorted by thematic category and designated into memos. Memos included a brief description of the theme, relevant codes, associated transcript IDs, and selected quotes, Memo and codebook excerpts can be found in Appendix B. The initial themes were reviewed and refined through re-review of the raw data for thematic consistency. Final themes were developed and defined. Detailed notes were kept throughout the analysis process.

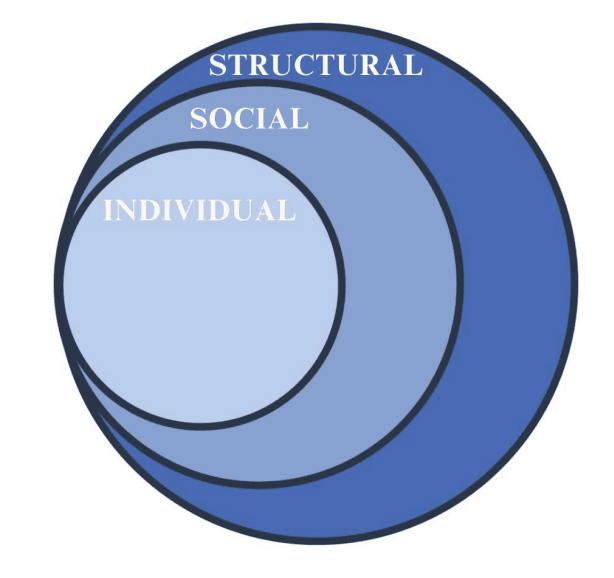

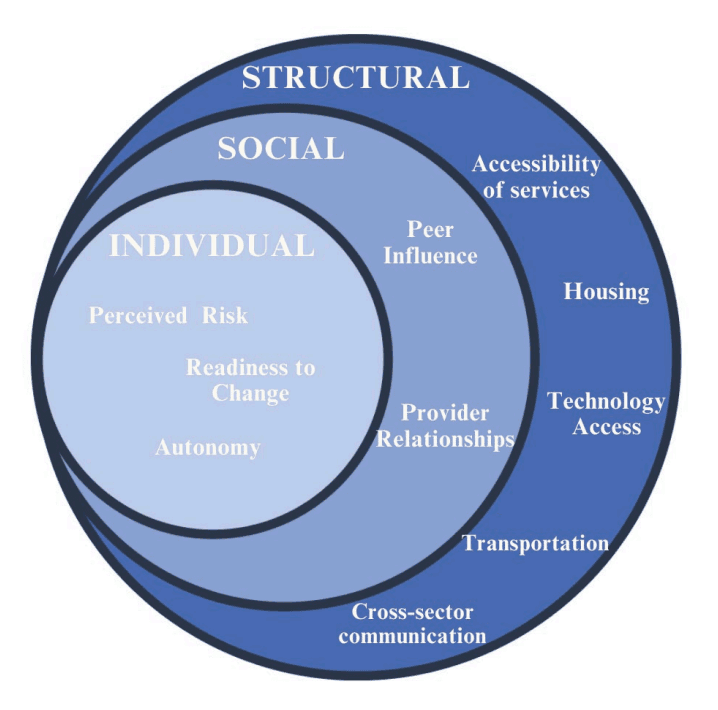

3.2.6 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study is based on an adapted version of the socioecological model (SEM). The adapted version is tailored specifically for PrEP use for individuals with CLI (Figure 3) (LeMasters et al., 2021). The SEM is a framework that separates factors influencing health into five levels: 1) individual; 2) interpersonal; 3) institutional; 4) community; 5) policy (Kilanowski, 2017). The adapted model collapses levels 3-5 (institutional, community, and policy) into one ‘structural’ category (LeMasters et al., 2021). This model is useful because it considers how health and health behaviors are influenced by complex systems. Classifying factors that influence health into these levels (individual, social, and structural) can facilitate targeted intervention development (CDC, 2022).

Figure 3: Adapted socioecological model for PrEP use in individuals with criminal legal involvement (LeMasters et al., 2021)

4.0 Results

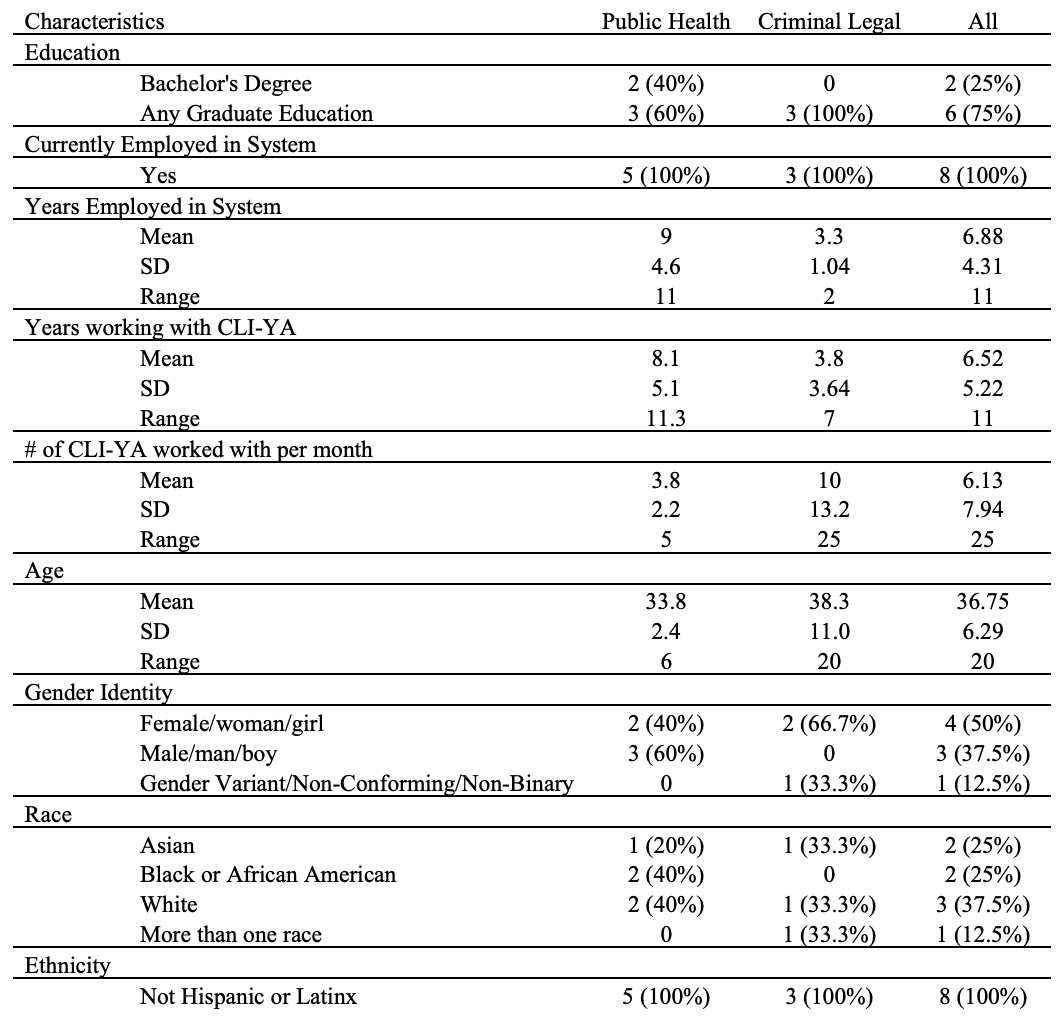

4.1 Demographics of Key Informants

There were eight key informants that participated in this study. Participants were recruited from the CL (n=3) and PH sectors (n=5). Participant characteristics can be found in Table 2. The plurality of participants identified themselves as White (37.5%) followed by Black/African American (25%), Asian (25%), and more than one race (12.5%). Half of the participants identified themselves as female/woman/girl (n=4), 37.5% identified as man/woman/boy (n=3), and 12.5% identified as gender variant/non-conforming/non-binary (n=1). All participants had received a bachelor’s degree, and most (75%) had completed some level of graduate education. All participants recruited from the CL sector had completed some graduate education, compared to 60% of those from the PH sector. The average length of time employed in their systems was 6.88 years. Participants form the PH system had been employed in the system for 9 years on average, compares to 3.3 years for CL system participants. Participants worked with an average of 6.13 CLI-YA per month. The numbers reported varied widely, with a standard deviation of 7.94.

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of key informants at time of interview (N=8)

4.2 Qualitative Findings of Key Informant Interviews

Analysis of the key informant interviews (n=8) led to the identification of four main themes that impact CLI-YA’s engagement in SU and HIV related services: 1) health and social services landscape; 2) life chaos; 3) relationships and social support; and 4) readiness to change and engage in services. While the approach was structured to identify barriers to engaging in SU and HIV related services separately, most participants reported overlapping factors that influence SU and HIV service engagement. The themes identified were consistent across participants’ discussions of SU and HIV related services and will be reported in aggregate, nuances in factors that contribute to SU or HIV related service engagement will be noted.

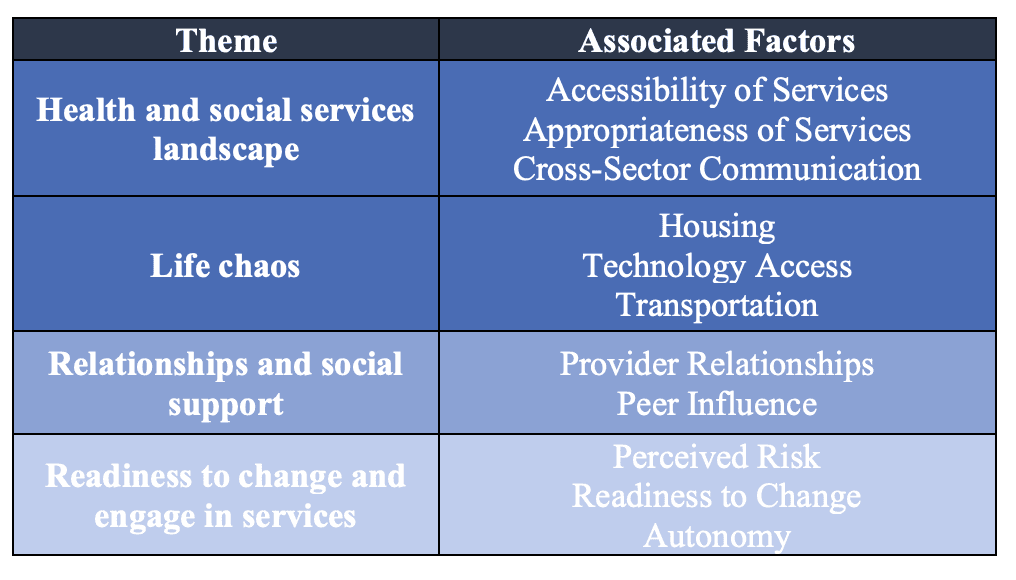

Factors associated with the health and social services landscape and life chaos were attributed to the structural level of the adapted SEM, factors associated with relationships and social support were attributed to the social level, and factors associated with readiness to change and engage in services were attributed to the individual level (Table 3, Figure 4).

Table 3: Themes and associated factors identified in key informant interviews

Figure 4: Factors associated with HIV and substance use service engagement for CLI-YA, as identified in key informant interviews, in the context of the adapted socioecological model of PrEP use for inddividuals with CLI

4.2.1 Health and Social Services Landscape

Most participants (n=7) reported barriers to engaging CLI-YA in services that were related to the health and social service landscape of the setting. Participants reported that the health and social service landscape influenced CLI-YA’s abilities to engage in HIV and SU related services, as well as meet their basic needs (e.g. housing, food). Barriers were classified into two sections: 1) accessibility and appropriateness of services; 2) communication between systems. Factors associated with the health and social service landscape were classified in the structural level of the adapted SEM (Figure 4).

4.2.1.1 Accessibility and Appropriateness of Services

Many participants (n=7) discussed the barriers that their patients/clients have encountered when trying access services. These challenges were related both to the accessibility of existing services (e.g. location, application requirements, legal barriers) and the appropriateness of the services. The appropriateness of services refers to whether the services available in the study setting were the optimal services for CLI-YA (e.g. non-judgmental, correct types of services). Most of the services that participants spoke about were related to basic needs (e.g. housing, food) and healthcare (e.g. SUT, HIV related services).

Multiple participants (n=6) spoke about their patient/client’s challenges making it to appointments because they didn’t have adequate transportation. Even when patient/clients had bus passes or other transportation assistance, the physical layout of the city presented a problem. Participants spoke about how their patients/clients often had to take multiple busses to appointments and that it could take hours to get there via public transit.

Participants also spoke about administrative barriers to accessing services. They discussed the process of signing up for public assistance programs (e.g. SNAP, insurance) and how complex application processes presented a challenge for their patient/clients. Many of the applications require extensive documentation that patients/clients frequently do not have on hand. Applying for services also requires reliable internet access, another barrier for CLI-YA. CLI-YA’s legal status also presented a barrier, especially if they were not living with HIV. A housing manager for PLWH spoke about how the Housing Opportunities for People With AIDS (HOPWA) program can sometimes be the only option for CLI-YA who need housing assistance:

“Depending on what their records are, they might no longer be eligible for a lot of subsidized housing access. If you have a felony that's not after 10 years and you would not be eligible for Section 8. You would not be eligible for housing authority. You would not be eligible for supportive housing no matter what your age is... I know for our younger crowd that I work with for housing, HOPWA is the only accessible thing for those kind of individuals that have records.” (Participant 8)

The appropriateness of existing services was also reported as a problem for CLI-YA, especially for those that are members of sexual and gender minority groups. Some participants who provide services for PLWH (n=4) spoke about the importance of referring their clients to LGBTQ+ affirming services, and how it can often be a deciding factor for their patients/clients when deciding to engage in services. This was frequently cited as a barrier for their patients/clients regarding housing and SUT programs. All four participants shared stories about their patients’/clients’ experiencing stigma related to their HIV status or LGBTQ+ identity and spoke about how it deterred their patients/clients from engaging in services. One participant said:

“I think that particularly when it comes to housing instability and the services that are provided to folks just aren't geared towards trans and nonbinary people. And so, there’s tons of women’s shelters. There’s tons of men’s shelters. But for the queer, nonbinary, gender-nonconforming folks, there’s not many programs or many beds that are specifically for them. And like I said, the fear of discrimination is across the board when it comes to feeling comfortable.” (Participant 7)

Participants also spoke about how often someone’s HIV care provider is a trusted resource, and how CLI-YA who are not living with HIV are less likely to have a trusted provider. When asked about barriers to engaging CLI-YA in PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) one participant said:

“I mean, that’s one of the pluses of someone who is living with HIV, is that they have that provider that they trust. With people who are not even engaged with PrEP, they don’t have that person yet.... I would imagine that it’s quite difficult when you don’t know who to go to.” (Participant 6)

Other factors associated with the appropriateness of services mentioned a lack of healthy food at food pantries and a lack of trusted SUT facilities. The importance of meeting clients where they are and employing harm reduction principles (e.g. meeting people where they are, being nonjudgmental) was a frequent topic of conversation. Participants expressed frustration at the limited number of SUT options that are not abstinence only and employ harm reduction principles. Both factors contributed to their CLI-YA patients’/clients’ hesitancy to engage in these services.

4.2.1.2 Communication Between Systems

Participants frequently discussed how communication between providers in different systems (e.g., physical health, behavioral health, social services, criminal legal) impacts their ability to provide services to CLI-YA and keep them in care.

Four participants spoke specifically about how communication, or lack of, between themselves and CL staff can impact patient engagement. These participants came from both the PH (n=3) and CL systems (n=1). Participants from the PH sector expressed frustration with the lack of communication and planning around jail discharge. The lack of communication was cited as a particular challenge when trying to reach patients/clients after they were released, particularly when patients/clients did not have phones or changed their phone numbers. Participants frequently spoke about how the jail did not tell them when their client was getting released, so they did not know to reach out to them to re-initiate services. One participant, a certified recovery specialist who provides peer navigation services in the jail and in the community, said:

“For the individuals that I have had that have been released, there's no communication between us and the jail at all... as far as any discharge plan or anything like that, there was no collaboration between us and the jail,” (Participant 5)

Similar sentiments were held around communication between different health systems. When discussing coordinating patient/client care with substance use facilities one HIV case manager said:

“Another issue with the substance use situation is trying to coordinate while someone's there. Honestly, I feel like it's the most impossible thing. And we'll get a release signed and everything. And it's just like crickets. It's like nothing. And then they're suddenly discharged. And they're calling you. Like, ‘Okay. I'm done.’ And it's months later, and you're like, ‘Oh, okay. They just dumped you out on the street? Why was there no communication with your provider? What the hell?’” (Participant 6)

Some participants (n=3) discussed how successful communication between sectors can act as a facilitator to engaging CLI-YA in care. Strong cross-organizational relationships were frequently cited when discussing successful referrals for CLI-YA. Participants spoke about the how having relationships with trusted organizations can facilitate warm-handoffs for CLI-YA, which aids in service engagement. Communication between service providers and parole officers was also mentioned as an important factor for CLI-YA when fulfilling court mandated tasks. One case manager discussed how communication with probation officers can help CLI-YA be more successful meeting their legal requirements:

“We've made sure, like, "Hey, if you have a PO, get this release signed so we can talk to them." And we've been in contact with them. And we've asked them, "When's their next hearing? When's drug court? How can I help them get there?" And they'll work with us.” (Participant 6)

4.2.2 Life Chaos

Another frequent topic of discussion was the chaotic nature of CLI-YA’s lives, particularly during the period immediately after release from jail. Six of the participants talked about the chaotic nature of their patient/clients’ lives and the ways it impacted engagement in services. Life chaos was frequently associated with challenges meeting basic needs, access to technology (e.g. phones, internet), and challenges specific to their CLI (e.g., benefits, court requirements). Many of the factors associated with life chaos for CLI-YA were attributed to the transitional period from jail back to the community. Factors associated with life chaos were classified in the ‘structural’ level of the adapted SEM (Figure 4).

Some SU and HIV service providers spoke about their patient/clients’ competing needs (n=4). Needs such as housing and food were most frequently cited as having to be met before their clients could effectively engage health in services. One provider, who identifies as a peer, said:

‘"Maybe I'm not even thinking about my food depravity because I'm homeless right now, and there's one thing that's more important to me than the other. And so maybe I'm food depraved, and maybe that is my first worry and not my HIV care."’ (Participant 7)

Unstable housing conditions were the most frequently mentioned contributor to life chaos. Four of the participants discussed challenges finding and contacting CLI-YA related to housing instability. When asked how they contact patients/clients when they have fallen out of care, participants reported varying levels of success. Providers who primarily reached out by phone, email, and letter reported the least success in re-engaging patients. The providers who reported the most success finding patients spoke about the importance of physically going out into the community to engage with patients/clients. When asked about strategies for contacting patients one provider, who works at a post-incarceration clinic, said:

“We physically go to the community to find people. Our community health worker will literally go to soup kitchens and abandoned houses to find our patients. And I think that's been our best way of engaging with this population.” (Participant 1)

Another barrier associated with unstable housing was a lack of privacy. Participants discussed patients/clients being wary of discussing sensitive topics related to SU and HIV over the phone because the housing/environment lacked privacy for the conversation. One HIV provider spoke about their patients’/clients’ challenges accessing medication in shared housing:

“Some might be staying at a halfway house, and they run into issues with their medications being stolen or not being provided for whatever reason. So, I think those are some of their barriers for why they may not remain in care.” (Participant 3)

Participants also frequently mentioned that CLI-YA typically have unstable access to phones, or that if they do have phones, they are frequently changing their number. Five of the participants spoke about challenges reaching CLI-YA related to their phone access. A specific issue that all five participants mentioned was that many CLI-YA do not have a phone when they get released from jail, so providers are unable to get into contact with them after they are released. Three of the participants spoke about challenges reaching patients/clients because their phone was lost, stolen, or their number had changed. One HIV case manager said:

“And especially people who are kind of coming in and out of jail. People have TextNow and Google Voice. And they have like 700 numbers. And you can't tell which one's which and which one they're not using anymore. And then a phone's lost. And I mean, I can't tell you how many times that's an issue, just that.” (Participant 6)

Participants spoke about the challenge of CLI-YA needing access to HIV medication, insurance, SNAP, housing, and employment all at the same time, immediately after release from jail. One of the participants expressed the urgency of accessing HIV medication after release from jail:

“So, I mean, if an individual is positive, they're going to need medication ASAP. I don't know how much medication they're coming out of jail with, but I'm always assuming little, next to none.” (Participant 8)

Three of the participants mentioned that many of their clients are frequently in and out of jail, which contributes to life chaos and makes it difficult for them to engage in care. One provider who works at a post incarceration clinic said:

Why don't people come to the clinic? It's because we can't get in contact with them. They don't have phones. They don't have technology. They don't have stable housing. When people leave incarceration, they're kind of jumping all over the place... the county jail is really a revolving door. People will kind of come in and out, in and out, in and out. And so, because of that, they're kind of bouncing all over the city too. So, finding people has really been one of our biggest barriers.” (Participant 1)

Three of the participants work for organizations that meet with CLI-YA while they are jail. All three of them spoke about the importance of meeting someone while they are in jail and forming a relationship, so that when they return to the community, they already have a connection. They spoke about how even when they have formed relationship with patients/clients while they are in jail, it can be challenging reaching patients and engaging with them once they return to the community because their lives become more chaotic. One participant, a certified recovery specialist, said:

“I think it's that uncertainty and just lack of stability after release. And also, I've had individuals, young adolescents that I've interacted with while they're incarcerated through video chat, and just there's a disconnect, I think, because the way that I would talk to them or communicate with them, it was just completely different to how once they're out I would get in touch with them. So, I don't know. That transition, that change and everything is difficult.” (Participant 5)

4.2.3 Relationships and Social Support

All of the participants spoke about the impact that relationships and social supports have on care engagement for CLI-YA. They spoke about the importance of their own relationship with their patients/clients as well as how peer dynamics shape how CLI-YA interact with health and social services. Peer relationships were divided into two categories: 1) peers in service settings (e.g., peer navigators) and 2) peers in the community (e.g., friends). Factors associated with relationships and social support were categorized in the social level of the adapted SEM (Figure 4).

4.2.3.1 Provider Relationships

Six of the eight participants discussed the importance of forming strong relationships with patients/clients and acting as part of their support system. They all spoke about how supportive relationships with patients/clients facilitates their engagement in care and that pushing past the provider/patient dynamic is important, especially for providers that are working within traditional healthcare settings. One housing manager for PLWH said:

“I feel like for this population base, making connections with their caseworker or whoever and feeling supported by institutions is what keeps them engaged in care.” (Participant 8)

Four participants spoke about the importance of connecting with patients/clients in person to really solidify their connection. They spoke about the change in dynamics when they engage with their patient/clients in person as opposed to virtually and how patients/clients are more ready and willing to open up and trust them. Other facilitators for building strong relationships with patients/clients included being non-judgmental, consistently showing up, and making sure your patients/clients know that you care about them on a personal level. When asked about the value of building relationships with CLI-YA patients/clients who are living with HIV, one participant said:

“I think that’s really, really important. I mean, I think having conversations about people’s goals and dreams makes them feel valued. I think a lot of people only speak to people about their health needs and their health goals. And in the world of HIV, it’s a broader picture that I like to paint because your well-being is not just about your T-cell count and your viral load. Your well-being also speaks to your mental health. It speaks to your hobbies and your loves and your pursuits.” (Participant 8)

Two of the participants spoke about how many CLI-YA do not have strong support systems, so providing them with a stable person who will show up is a major facilitator for care engagement. When speaking about engaging CLI-YA in SU services, one participant said:

“I think for a lot of this population, it’s like they’ve never had anyone really show up for them, really show up, I think just being there, right, a face that they constantly see. I think that that’s kind of where this community health worker and peer navigator stuff has really worked out is we have people who are just there. And we don’t judge them. We don’t take for granted what they’ve been through. We don’t question them about their experiences or why they’re using, why they’re not using it. It’s like, “Hey, I just want you to live.” And I think when you frame conversations about substance use with anyone, but especially this population, about I want you to live, I want you to see your 30s, it’s a very different conversation.” (Participant 1)

4.2.3.2 Peer Relationships

Six of the eight participants spoke about the influence that their patients’/clients’ relationships with peers had on service engagement. Peers were divided into two categories: 1) peer-providers (e.g., peer navigators) and 2) peers in the community (e.g., friends).

4.2.3.2.1 Peer-Provider Relationships

Peer-providers were defined as service providers that share similar characteristics with their clients such as a history of SU, race, age, or a history of CLI. Peer-providers discussed by participants included community health workers, certified recovery specialists, and case managers who disclosed their peer status to their clients.

Two of the participants identified themselves as peers and discussed the nuance of the dual peer provider relationship. Both spoke about how their peer status facilitates building string relationships with their patients/clients because they know they have been through many of the same things. They trust their referrals and are also more willing to take their advice. One participant spoke about how their peer status not only breaks down barriers and make patients/clients feel less judged, but it also shows them that recovery is possible:

“I know what the misery and the hopelessness and what all that feels like, but then I also know what it feels like to heal and recover. And I guess a common analogy I use is the four-minute mile where everybody thought it was impossible until somebody did it. And then all of a sudden, after that, it wasn’t this impossible thing anymore, and more and more people kept beating that sort of record. So, I just sort of compare it to that. Because it’s hard. When you’re in the middle of that addiction, you think like, ‘There’s no way I can live without it. That’s like telling me to stop breathing or stop drinking water, and you’ll survive.’” (Participant 5).

Four participants who did not identify as peers, spoke about the importance of having peer navigators or community health workers as members of their CLI-YA patients’/clients’ care teams. Their reasoning reflected the sentiments that the two peer participants shared, that it is important for CLI-YA to have someone who knows what they have been through and will not judge them.

4.2.3.2.2 Peer Relationships in the Community

Four of the participants spoke about how peer relationships in the community (e.g., friends) influence substance use behaviors and service engagement. Three of them spoke about peer influences on CLI-YA and how when they are around people who are using drugs or participating in criminalized behaviors, they are more likely to do the same and less likely to engage in services. When discussing the role that age plays in SU service engagement, one participant said:

“The other thing is when I think about people in their 20s and substance use specifically... you think about people who are participating a lot more hazardous and risky drug use... It is people who maybe are getting exposed to heroin for the first time in their lives, right, or the people that they’re hanging out with are young people who are also using drugs.” (Participant 1)

Two participants spoke about the importance of peer spaces, like support groups, for CLIYA living with HIV. They spoke about how they can be valuable tools for reducing isolation and stigma and improving mental health and substance use outcomes. Participants also mentioned that when their CLI-YA patients/clients have strong social support systems they need less support from their providers.

4.2.4 Readiness to Change and Engage in Services

Five of the participants discussed factors that impact CLI-YA’s readiness to change and engage in services. Readiness to change can be conceptualized within the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). This model identifies five stages of behavior change: 1) precontemplation; 2) contemplation; 3) action; 4) maintenance; and 5) termination (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Based on participant discussions of their clients/participants readiness to change and engage in services, many of their CLI-YA patients/clients fall into the precontemplation stage, which means they are not intending to make a change in their behavior in the foreseeable future.

Participants spoke about CLI-YA’s health beliefs (e.g., risk perception), their stage of life, and intrinsic motivation as important factors that influence CLI-YA’s readiness to change and engage in services. Factors associated with readiness to change and engage in services were categorized in the individual level of the adapted SEM.

Three of the participants spoke about how many of the CLI-YA they work with do not think they are at risk for HIV, even if they are. A common sentiment about HIV, SU, and other services was that if their patient/client does not think they need a service, they will not engage with it. When discussing a typical referral process one participant said:

“We also ask like, "In the last 90 days, have you had unprotected sex?" And things like that. That's a sexual health referral that we do. But some people just are not interested in going to those. And so, we may want you to go to that. But if you feel like internally, your sexual health is fine, then that’s not a need. So, to answer your question in short again, specifically, if we feel as though, "Do you want to go take an HIV test?" No, they don't.” (Participant 7).

This was also a challenge mentioned related to SU services. Two of the providers spoke about how the CLI-YA they work with are less likely to think their SU is hazardous than their older patients/clients. The result being that they are also less likely to engage in services. They both discussed how the experience of young adulthood can make people feel invincible, and that the consequences of hazardous drug use often have not caught up with them yet. One SU provider said:

“I remember being in my 20s, and I felt like I could do anything. Right? I felt like the world was infinite. And so, if you think about just being a 20-year-old and substance use, yeah, I mean, it doesn't feel like anything bad could happen, or the bad things aren't going to touch them because they're so young and physically fit still. They're not dealing with years of damage just like growing old does.” (Participant 1)

Five participants said that their CLI-YA patients/clients do not like being told what to do. A common sentiment among participants was that telling someone they need something, rather than letting them come to that conclusion on their own, often makes them defensive and less willing to engage in services. All five of the participants expressed the value of guiding their patients/clients to finding their own intrinsic motivation for engaging in services. They spoke about how their patients/clients need to be ready to change and feel like they need a service (e.g., HIV, SU, healthcare generally) before they are receptive to recommendations. Two participants spoke about the importance of motivational interviewing when engaging patients/clients in SU and HIV related services. One participant, who is a certified recovery specialist, said:

“I really like to use motivational interviewing and stuff like that, have people come to those sort of decisions themselves because, a lot of times... it's difficult because there's that sort of, "This isn't going to happen to me," type of vibe or like, "I can get through this or whatnot." And I think there are, unfortunately, some experiences that you have to come to on your own or you just have to experience, be like, "Oh, okay." At least, probably, when it comes to substance use disorder.” (Participant 5)

5.0 Discussion

5.1 Public Health Significance

This study explored the factors that influence CLI-YA’s engagement in HIV and SU related services from the perspective of service providers from the PH and CL systems. The findings of this study will contribute to the literature on service engagement for CLI-YA upon release from jail. While the literature on linkage to HIV care after jail release is relatively robust, there is limited data on integrated HIV and SU service linkage upon release from jail (Grella et al., 2022). The literature on HIV and SU service linkage (integrated or stand-alone) tailored to CLI-YA on release from jail is even more limited (Siringil Perker & Chester, 2021). Studies have found that CLI-YA are less likely to be virally suppressed if they have HIV (Ickowicz et al., 2019), and more likely to experience fatal drug overdoses than their older counterparts (Selen Siringil Perker & Lael E. H. Chester, 2018). However, there have been few studies examining the factors that contribute to this. Only one study was found that examined factors associated with post-jail reentry program retention for CLI-YA, and while they found that CLI-YA had lower retention rates than their older counterparts even after controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, history of being unhoused, and behavioral health diagnosis, they did not identify specific factors that caused this (Barnert et al., 2024).

Identifying specific factors that influence CLI-YA’s engagement in HIV and SU related services could aid researchers in developing interventions that are specifically tailored to CLI-YA, which could improve engagement and retention for this population and improve health outcomes related to HIV and SU for CLI-YA . Speaking to service providers, as opposed to CLI-YA, offered insight into the ways that CLI-YA engage in HIV and SU services differently than their older counterparts. Service providers who work with both CLI-YA and older adults were able to speak to the factors specific to CLI-YA that act as barriers or facilitators to service engagement and how they compare to those of their older counterparts. The main themes identified that influence HIV and SU service engagement for CLI-YA were: 1) the health and social services landscape; 2) life chaos; 3) relationships and social support; 4) readiness to change and engage in services.

These themes, and the associated factors, can be classified within the context of the SEM of PrEP use for CLI individuals (Figure 4) (LeMasters et al., 2021). Organizing factors that impact HIV and SU service engagement for CLI-YA within the context of the SEM (Figure 4) provides a framework for where to target strategies to address barriers.

There were several factors identified that were specific to HIV and SU service engagement for CLI-YA when compared to their older counterparts. This included factors at the structural level (e.g., housing program eligibility), social level (e.g., peer influence, relationship building strategies), and individual level (e.g., risk perception). Though participants did discuss factors specific to YA, they were not asked about factors specific to older CLI individuals and therefore I cannot fail to reject the hypothesis that service providers will report that YA (18-29 years old) who have been involved with the CLS face more barriers to engagement in HIV and SU services in the community than their older counterparts (>29 years old).

5.2 Implications for Jail to Community Transition Planning for CLI-YA

One of the biggest barriers that service providers discussed was the chaotic nature of CLIYA’s lives, particularly around the time of release from jail. Many of these factors were related to structural barriers that are directly related to incarceration. Service providers expressed frustration with lack of communication around discharge planning and said that they often don’t know when their clients are released from jail which makes it difficult for them to get into contact with them. They spoke about how their patients/clients frequently do not have phones when they are released, which means the providers have no way of contacting them, and their clients/participants had no way of contacting providers. This was also a challenge for providers that meet with their clients while they are in jail. Even though meeting with their patients/clients while they were incarcerated facilitated relationship building, they often did not have their patients’/clients’ phone number and did not know where they were going after they were released. This frequently resulted in their patients/clients falling out of contact upon release.

Addressing the structural barrier of limited discharge communication and planning between jails and CLI-YAs’ service providers could improve rates of engagement in HIV and SU related services for CLI-YA. Involving service providers directly in the discharge planning process would not only give them more information about when their patients/clients are going to be released, it could also foster a smoother transition process for CLI-YA. Participants spoke about the importance of forming strong relationships with their CLI-YA patients/clients. The input of service providers who really know their patients/clients personally could help jail staff formulate individualized discharge plans, which could reduce the chaos experienced by CLI-YA when they return to their communities. The discharge planning process should include assistance re-applying for insurance, SNAP, and other social programs that individuals lose access to when they are incarcerated. It should also include providing them with a standardized medication allowance and referrals to food and housing services. This would ensure that more of their basic needs are met when they return to the community. Service providers discussed the importance of making sure their patients’/clients’ basic needs are met and said that until their basic needs are fulfilled their patients/clients are often less engaged in HIV and SU services.

Potential barriers to this recommendation include staffing storages, short lengths of stays, and rapid turnover times in jails (Heffernan & Li, 2024; Zeng, 2022). These could be significant barriers to creating individualized discharge plans for CLI-YA. Jails experience an average weekly turnover rate of 41% (Zeng, 2022). Creating comprehensive, individualized discharges plans for 41% of the jail population each week could be challenging, particularly if the jail is understaffed. However, if standardized processes are developed, including service providers in the discharge planning process could reduce some of the burden that comprehensive, individualized discharge planning would have on jail staff.

Another structural factor cited as making the release period particularly chaotic for CLIYA was a lack of stable housing. Participants expressed that this made it challenging to reach their patients/clients, that it impacted their ability to speak to their clients/patients over the phone, and that it made getting medications to their clients challenging. Involving service providers in the discharge process could make it easier for them to find their patients/clients even if they do not have stable housing, but it would not necessarily address issues associated with privacy and medication access. Additionally, even if service providers know where their patients/clients are going when they are released from jail, if patients/clients do not have access to stable housing, they may not stay in one place for long. It would be ideal to implement low barrier housing assistance programs specifically for CLI-YA who are leaving jail.

One of the simplest ways to address the challenge of finding CLI-YA after they are released from jail would be providing them with phones upon release. It would be important to make sure they have a cellular plan that includes internet and is paid for for at least a few months. Ensuring service providers have their patients/clients phone numbers and that the phones are preprogrammed with phone numbers for service providers and crisis resources could significantly improve efforts to re-engage CLI-YA in SU and HIV related services upon release from jail. While the cost of providing phones could be significant, there are existing programs that offer free or reduced cost phones to individuals who are eligible for other social services ("Stay Connected with the Lifeline Telephone and Broadband Assistance Program ", 2020). Leveraging these existing programs could help offset the costs associated with phone distribution.

5.3 Implications for HIV and Substance Use Services for CLI-YA

Participants often spoke about the barriers to engaging CLI-YA in SU and HIV related services in tandem. Many of the barriers between the two were shared and mirrored wider issues related to service linkage and engagement in general for CLI-YA. Additionally, most of the participants provided either SU or HIV services to their patients/clients and spoke mostly from that perspective. This is likely due to the siloed nature of SU and HIV services, which has been attributed to the common practice of having separate insurance payor systems for behavioral and physical health services (Scott et al., 2023).

The most frequently discussed facilitators for engaging CLI-YA in HIV and SU services were social and individual factors including strong relationships, non-judgmental care, the inclusion of peers (e.g., peer navigators, community health workers, certified recovery specialists) in healthcare spaces, fostering the development of intrinsic motivation, and allowing for autonomy in their care decisions. These facilitators are aligned with some of the core tenants of harm reduction (Table 4) ("Principles of Harm Reduction,"). Harm reduction is defined by the National Harm Reduction Coalition as “a spectrum of strategies that includes safer use, managed use, abstinence, meeting people who use drugs “where they’re at,” and addressing conditions of use along with the use itself” ("Principles of Harm Reduction,"). While the harm reduction principles are specifically tailored to PWUD, they have also been adapted to the context of HIV and are relevant across both issues (L. Brinkley-Rubinstein, Cloud, Drucker, & Zaller, 2018).

Facilitator | Harm Reduction Principle |

|---|---|

Non-judgmental care | Calls for the non-judgmental, non-coercive provision of services and resources to people who use drugs and the communities in which they live in order to assist them in reducing attendant harm |

Including peers (e.g., peer navigators, community health workers, certified recovery specialists) in healthcare spaces | Ensures that people who use drugs and those with a history of drug use routinely have a real voice in the creation of programs and policies designed to serve them |

Fostering the development of intrinsic motivation, Allowing for autonomy in care decisions | Affirms people who use drugs (PWUD) themselves as the primary agents of reducing the harms of their drug use and seeks to empower PWUD to share information and support each other in strategies which meet their actual conditions of use |

Table 4: Facilitators to care engagement for CLI-YA and their associated harm reduction principles ("Principles of Harm Reduction,")

Participants frequently spoke about how their CLI-YA patients/clients do not like being told what to do and that using motivational interviewing techniques can help guide them to wanting to engage in services of their own accord. Motivational interviewing was specifically mentioned by both SU and HIV service providers. They also discussed how including peers in service delivery settings, such as community health workers and certified recovery specialists, facilitates service engagement for CLI-YA. This was attributed to shared experiences which result in an increased trust in referrals and a decreased fear of judgement for CLI-YA. This highlights the need for HIV and SU programs that incorporate harm reduction principles by including peers, prioritizing client/patient preferences, and empowering clients/patients to make their own decisions.

Participants also spoke about the importance of framing referrals to HIV and SU related services as a part of care as usual, to avoid clients/patients getting defensive and thinking that they’re being told something is wrong with them. This speaks to the bigger issue of HIV prevention and SU services being siloed from standard primary care settings (McGinty, Stone, KennedyHendricks, Bachhuber, & Barry, 2020; Sell, Chen, Huber, Parascando, & Nunez, 2023). While testing for sexually transmitted infections is standard in primary care settings, referral to PrEP is generally not (Sell et al., 2023). The same is true for referrals to harm reduction based SU services and the prescription of medications for addiction treatment (Jawa et al., 2023). Embedding these services in primary care could serve to destigmatize them, and encourage more people, and more CLI-YA, to engage with them. Though this could facilitate care engagement for CLI-YA who are already somewhat engaged in care, it would not reach CLI-YA who are not engaged in care at all. There are also significant barriers to implementing this recommendation. It would require an overhaul of existing insurance payer policies (Scott et al., 2023) and garnering institutional buy-in.

5.3.1 HIV Prevention and Treatment

Factors specific CLI-YA’s engagement in HIV prevention and treatment services were discussed primarily on an individual level. Risk perception was frequently discussed as a barrier to engaging CLI-YA in HIV prevention services. When participants spoke about their experiences working with their CLI-YA patients/clients who are not living with HIV, a common sentiment was that they do not think they need to be tested for HIV or take PrEP because they do not think they are at risk for HIV. This is a challenging issue to address, if CLI-YA are precontemplative they will not be motivated to make a change in their health behaviors (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Including education on HIV risk factors and prevention methods during the referral process could help move them to the contemplative stage, but it would need to be done non-judgmentally and in a way that does not make the patient/client feel as if they are being told what to do. The integration of HIV related services into the primary care setting could also help address this by normalizing and destigmatizing HIV services.

5.3.2 Substance Use Services