Abstract

While research on substance use disorder (SUD) treatment among justice-involved populations has grown in recent years, the majority of corrections-based SUD studies have predominantly included incarcerated men or men on community supervision. This review 1) highlights special considerations for incarcerated women that may serve as facilitating factors or barriers to SUD treatment; 2) describes selected evidence-based practices for women along the cascade of care for SUD including screening and assessment, treatment and intervention strategies, and referral to services during community re-entry; and 3) discusses conclusions and implications for SUD treatment for incarcerated women.

Introduction

Rates of substance use in the United States (US) continue to rise, with the number of individuals endosing past month illicit substance use increasing from approximately 27 million in 2015 to more than 37 million in 2020. Nationally representative data indicate that prevalence rates for drug use are generally higher among men than women, although the gender gap in use and SUD in the US has narrowed in recent years. Among individuals involved in the justice system, the gender gap is reversed with a higher proportion of incarcerated women than men meeting criteria for SUD in both US and international samples. In the last 40 years, the number of incarcerated women has grown more than six times since 1980, an increase of 525%. Driven largely by drug use and drug-related charges, the rate of arrests and incarceration among women has grown two-times that of men, with the rate of drug-related charges increasing more than 200% for women in the past three decades. Among US individuals, about half (50.8%) of incarcerated women in prisons are expected to meet SUD criteria for illicit drugs, compared to about a third (38.5%) of men. In addition, it estimated that prevalence of SUD among incarcerated women in jail settings is even higher than those in prison.

In recent years, there have been national and international calls for a shift to a public health approach to addressing SUDs rather than a punitive approach. However, most mind-altering substances remain illegal, which increases the likelihood of significant overlap between substance use and involvement with the criminal justice system. Some criminological theories have attempted to explain the connection between illicit substance use and crime. For example, Canadian and Australian researchers have attempted to understand this relationship using “attributable risk”, which includes asking incarcerated individuals to assess the extent to which their illegal activities were attributed to the need to obtain or maintain their substance use, or if they attribute their commission of illegal activities as being independent of their substance use. This work was expanded to better understand attributable risk by gender among incarcerated individuals. Findings indicated that a higher percentage of women (31%) attributed their illegal activities to substance use compared to men (18%). While these studies suggest a strong connection between substance use and crime, gender differences underscore the need for future research on the unique and individualized trajectories of these behaviors which has important implications for SUD treatment in justice system settings.

These trajectories of substance use and crime could also be viewed through the lens of feminist criminology theories including a gendered pathway framework, which indicate that we “must account for the myriad ways that gender matters”. This framework suggests that a woman’s criminal behavior (and perhaps criminal career) is often characterized by a history of interconnected experiences with violence and victimization, trauma and mental health issues, problematic and high-risk relationships, and a general lack of social or financial capital. Because all of these factors are compounded substance use, gendered pathway frameworks also lend themselves to understanding the trajectory of women’s substance use, and the subsequent emerging cycle between substance use and criminal activities. Considering the longitudinal nature of these behaviors over time, women’s recovery pathway should also be individualized with the understanding that options for treatment and recovery strategies which “work” for one woman may not be applicable for all women.

These theoretical perspectives on the intertwined pathways of substance use and criminal activity among women are important in understanding SUD treatment utilization and other services. While research on SUD treatment among justice-involved populations has grown in recent years in the US with rigorously designed, controlled clinical trials on medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD), and other successful evidence-based practices, the majority of corrections-based SUD studies have predominantly included incarcerated men or men under community supervision. The purpose of this review is to 1) highlight special considerations for incarcerated women in the US that may serve as facilitating factors or barriers to SUD treatment; 2) describe selected evidence-based practices for women along the cascade of care for SUD including screening and assessment, treatment and intervention strategies, and referral to services during community re-entry; and 3) discuss conclusions and implications.

Special Considerations for Incarcerated Women with SUD

Parenting Status

Incarceration is a stressful and chaotic event for women with children. Parenting responsibilities are often a barrier for women to enter SUD treatment, and can be even more of a challenge for incarcerated women. An estimated 57,700 women in US state and federal prisons have minor children. The effect of incarceration on both mothers and their children has been documented, and the negative consequences may be even more pronounced for mothers who used substances before incarceration. For example, incarcerated mothers’ separation from their children has been associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and tendencies toward self-harm. Also, when considering the high-risk lifestyles many women may have had before incarceration associated with substance use and criminal behaviors, there may be a considerable amount of shame associated with the stigma of being an incarcerated mother. In addition, incarceration presents challenges for maintaining a connection with children and attempting to protect them. Maintaining a connection through regular contact with children is critical and protective for mental health issues among incarcerated women, as well as a predictor of successful reunification during community re-entry.

While studies of pregnant incarcerated women have found similar issues associated with substance use, trauma, and mental health, these issues also raise concerns for unborn babies and for treatment opportunities during community transition. For opioid use disorder specifically, Sufrin et al found that a majority of US jails and prisons in their sample prescribed MOUD for women who were pregnant, but most prisons and half of the jails only provided continued MOUD community treatment referral rather than the provision of medication. In addition, the majority of prisons (about two-thirds) and jails (about three-fourths) discontinued MOUD following the birth of the baby. While some women may receive better prenatal care in prison than in the community due to poverty, risky lifestyles, and other factors there has been a call in recent years to support standards of care in state and federal correctional facilities for pregnant women with SUD and newborns.

There are also a number of negative consequences for children of incarcerated mothers, which may be associated with attachment issues at different developmental stages. Incarceration can be traumatic event for children with mothers being removed from the home and children living with a family member or in foster care, including environment stress that may exist before prison due to drug use and other risky lifestyles. While there may be variation in the impact on children and youth associated with maternal incarceration due to many potential factors, substance use in the home and the degree of mother’s problem severity may be critical in the long-term consequences. These findings indicate that SUD treatment for incarcerated women who are pregnant or parenting is critical – not only for them, but also for their children.

Trauma, Victimization, and Co-Occurring Mental Health

A history of trauma is a consistent factor found in the SUD literature among incarcerated women. Among incarcerated women in general, rates of lifetime trauma and victimization among incarcerated women are high, and rates are even higher among women with a history of substance use. Research suggests that roughly three-quarters of incarcerated women with SUDs have experienced some form of lifetime traumatic or distressing event. The rates of victimization and trauma among these women underscores the critical importance of trauma-informed treatments and services incarcerated women with SUDs, which has been consistently reported in the literature. For example, in one study of perceived treatment needs among incarcerated women, a majority with SUDs reported a need for treatment that included a focus on prior child abuse and domestic violence. There is a continued need for efficacious SUD treatment that incorporates the traumatic histories of incarcerated women.

Among justice-involved women with SUD, trauma and violence histories are also often associated with co-occurring mental health issues. For example, one study found that women incarcerated in jail or prison are more likely to report both serious distress and mental health histories compared to men. Much like the trajectories associated with substance use and crime, mental health factors are closely associated with substance use for women, potentially increasing their vulnerability for victimization and/or additional distress. Alternatively, some women with trauma histories, experiences of physical pain, or mental health issues may also use illicit substances to cope with stressful situations.

The prevalence of co-occurring mental health issues among incarcerated women was estimated through a meta-analysis at approximately 10.1%. Another study of incarcerated women specifically suggested the prevalence rate might be higher at 20%. Commonly reported co-occurring disorders (CODs) include anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and bipolar disorder, although much of the literature has been limited in the number and types of co-occurring mental health disorders assessed.

Despite high prevalence rates, individuals with CODs frequently do not receive treatment in the US, and even less for incarcerated women. Nowotny et al found that approximately 71% of their sample of incarcerated women with CODs reported receiving no COD treatment in the past year. These low treatment rates for CODs may be due to accessing integrated treatment barriers. Most treatment for incarcerated women with SUDs is primarily aimed at reducing substance use through behavioral interventions like therapeutic communities or medications for pregnant women, ignoring potential psychiatric problems that may exacerbate substance use and/or contribute to relapse. hus, co-occurring mental health issues, particularly if compounded by trauma and victimization histories, are critical to consider in designing and implementing SUD interventions for incarcerated women.

Health and Transmitted Infections

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, compared to the general population, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is three times higher in state and federal prisons. For justice-involved women, the risk for HIV and other blood-borne illnesses is often linked to risky sexual practices before incarceration such as unprotected sex or exchange sex. For example, one study of incarcerated women in rural Appalachian, more than one-quarter reported having traded sex for drugs, money, or other services in the year before incarceration. There is also evidence to support a correlation between arrest and/or incarceration and number of different sexual partners, occurrences of unprotected sex, and concurrent partners.

Among justice-involved women who use substances, risky sexual practices appear to be even more common. For women who have engaged in high-risk drug use (eg, injection and overdose), the risk for blood-borne infections, including both HIV and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) may be further amplified. Disease transmission among women who use illicit substances is also intertwined with risky romantic partnerships, with studies pointing to a number of vulnerabilities, such as having a sexual partner who injects drugs or being injected by a partner.

As the rate of women in the justice-system continues to rise, incarceration becomes an important opportunity for HIV/HCV prevention efforts, including risk reduction interventions focused on known risk factors. From community corrections settings to prisons, interventions targeting women most at risk for acquiring HIV/HCV have had positive outcomes. Furthermore, interventions tailored to focus specifically on the unique needs of women are particularly promising, but research in this area is limited. Thus, SUD treatment interventions for incarcerated women should be designed with an eye toward HIV/HCV and other infectious disease risk reduction.

Race/Ethnicity

Although often unacknowledged in the substance use and crime literature, the potential impact of critical factors such as structural and systemic racism on the financial opportunities, health and health service access, and criminalization of women of color must also be recognized as in understanding criminal activity and justice system involvement. While there are studies focused on understanding substance use among racial/ethnic minorities, women, and those with criminal justice involvement, there is limited intersectional research investigating substance use among justice-involved women of color.

Bronson et al ound that, among incarcerated individuals, women and White individuals are more likely to meet criteria for substance use disorders than men and Black or Hispanic individuals. However, other research on justice-involved women specifically found no differences by race among women on lifetime history of substance use disorders. Despite these similarities in overall use patterns, the type of SUD which incarcerated women experience may differ by race/ethnicity. The results of one study with incarcerated women suggested that among those who met substance dependence criteria, a higher percentage of Native American women met alcohol and heroin dependence criteria, a higher percentage of Black women met cocaine dependence criteria, and more White women met stimulant dependence criteria.

Findings related to substance use treatment utilization disparities by race/ethnicity for justice-involved women have shown mixed results. Although some research suggests that White justice-involved individuals are more likely to have been engaged in substance use treatment than people of color in mixed-gender studies, other studies with justice-involved women did not find race/ethnicity differences in substance use treatment utilization However, specific treatment needs for justice-involved women of color with SUDs have been documented, such as HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) risk and race-based stigma surrounding incarceration and substance use. hese unique patterns of substance use, health risk behaviors, and racial stigma among women of color should be taken into consideration in SUD treatment approaches.

Rural/Urban Populations

Geographic context (living in a rural or urban area) has been shown to be important to understand women’s substance use patterns, as well as substance use treatment utilization following release from incarceration. Although living in a rural area has traditionally been considered protective for substance use, research has found similar levels of SUD in rural and urban justice-involved women, yet rural women access substance use treatment at lower rates than urban women. Limited service availability in rural areas is the major reason for this disparity in substance use treatment utilization. When rural women do access substance use treatment, not all evidenced-based treatment approaches like MOUD are offered. In one national study of substance use treatment centers, researchers found that rural treatment centers offered fewer treatment options, had less educated clinical staff, and were less likely to prescribe buprenorphine.

In addition to the general problem of service availability, rural women face other challenges accessing existing substance use treatment. First, with less comprehensive reentry programs in many rural areas, women may be less likely to receive SUD treatment referrals at community reentry. Second, although not a unique barrier to rural women, transportation is more limited and distances to treatment in rural areas are often greater than in urban areas. Public transportation options are fewer, and there is a greater reliance on family and friends for rides, all of which magnify transportation problems for rural women. Third, other studies have shown that rural women have fewer socioeconomic/employment opportunities resulting in financial barriers to paying for substance treatment.

In addition, cultural issues in rural areas may deter women from accessing substance use treatment. Rural communities often promote a culture of self-reliance and distrust of outsiders, which may make rural women less likely to seek SUD treatment. Rural women tend to have denser social networks, may be more integrated into their communities, and therefore experience less anonymity. This may make it more difficult to keep their treatment and justice status private, which may subsequently increase the likelihood of experiencing stigma. Thus, cultural issues in the design and implementation of SUD treatment programs for incarcerated women should include both women of color and women from under-represented geographical areas such as those living in rural communities.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Sexual orientation and/or gender identity are other considerations among incarcerated women with SUD. This may include women who are of a minority sexual orientation, including lesbian, bisexual, or queer, as well as transgender women. Transgender men and agender and/or non-binary individuals should also be considered, since they may have been assigned female at birth, can share biological features in common with cisgender women, and might at times present as, and/or be perceived as, feminine by others. Within the criminal justice system, housing and classification are most often assigned by biological sex, the term “women” is used here to refer to individuals who may identify as women, but also those individuals who may be viewed as women from the perspective of correctional staff.

Within this inclusive definition, the minority stress model is a useful theory for understanding SUD treatment considerations for LGBTQ+ women. This theory proposes that sexual minority populations may experience health disparities that are a direct result of persistent individual, interpersonal, and structural stigma which lead to poor health through various psychosocial and physiological mechanisms. The framework is supported by research that has consistently documented that LGBTQ+ individuals report higher rates of SUD and related problems when compared to heterosexual and/or cisgender individuals. Furthermore, although community-based SUD treatment programs which offer tailored services to LGBTQ+ individuals have increased in recent years, treatment options remain limited, and even more limited in corrections. Understanding that LGBTQ+ women may also experience additional stress through bias and discrimination in the justice system, it is critical that resources are allocated to increasing SUD treatment in carceral settings that are affirming, inclusive, and that offer integrated, trauma-informed care.

Cascade of Care for Incarcerated Women with SUD

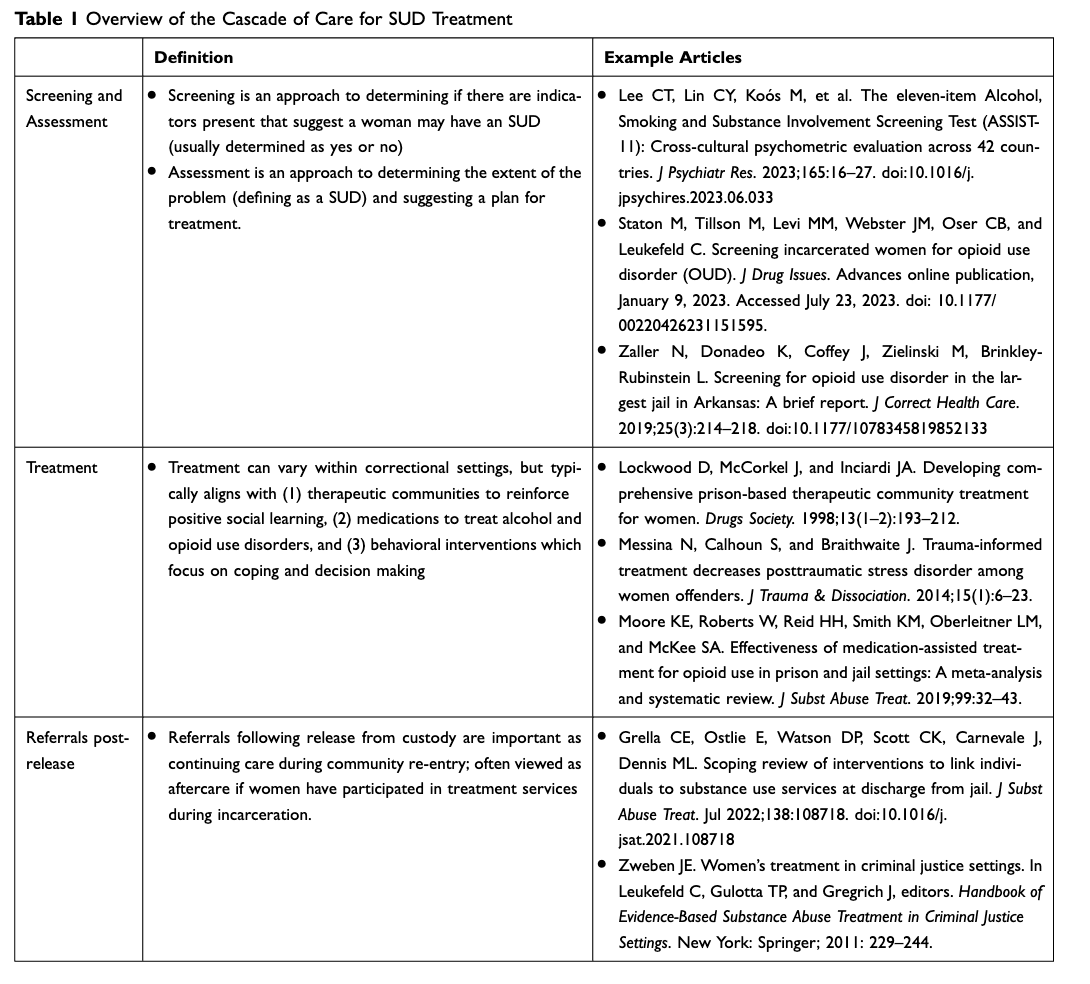

The previous sections have highlighted a number of special considerations for incarcerated women which have been well documented as factors which may facilitate or hinder SUD treatment engagement and retention. The following section is conceptually grounded in the cascade of care framework for SUD treatment. The cascade of care was developed as an organizing framework for the continuum of HIV services from diagnosis, linkage to care, treatment retention, medication receipt, and viral suppression. The framework has been applied to SUD treatment by the NIDA-funded Juvenile Justice – Translational Research on Interventions for Adolescents in the Legal System (JJTRIALS) cooperative agreement to assess engagement and retention of juvenile-justice services along the cascade, as well as to define outcomes for OUD screening/assessment, diagnosis, care linkage, medication initiation, medication retention, and sustained abstinence. The cascade of care framework (See Table 1) is used here to overview the literature on SUD screening and assessment, treatment and intervention approaches, and referrals following release of incarcerated women with SUD.

Table 1 Overview of the Cascade of Care for SUD Treatment

SUD Screening and Assessment

One national study showed that more than half prisons surveyed did not include SUD screening and assessment as part of standard intake procedures, and these practices were even more limited in county jails. Considering the high SUD rates and co-occurring mental health issues among incarcerated women, correctional settings provide important opportunities for SUD screening and assessment and needed linkages to treatment in both carceral settings and during community re-entry. Other settings (eg, health care settings, pharmacies) have adopted evidence-based screening approaches to identify individuals at high risk for SUD, as well as through behavioral trials. World Health Organization (WHO) developed and validated the Alcohol Smoking Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) to identify individuals at risk for substance use disorders in health care settings. The ASSIST was later adapted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to include separate unique categories of opioid use (prescription opioids vs street opioids), as well as stimulant use (NIDA modified-ASSIST [NM-ASSIST]). The NM-ASSIST is quick to administer (5–10 minutes), is easily scored to understand the need for intervention (4+), and has been administered with individuals at high risk for substance use in criminal justice settings. Staton et al found that that incarcerated women randomly selected from jails and screened for OUD following a single item to assess past year opioid use reported NM-ASSIST opioid scores that were considerably higher than non-incarcerated samples, and other samples of incarcerated women. The ASSIST has also been validated as a shorter, 11-item scale with individuals across 42 countries and 26 languages.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders-5 Checklist is another example of an SUD screening tool which assesses risk along a list of eleven criteria associated with SUD in the past year with severity ranging from mild to severe, and a score of two or higher being consistent with a SUD. While widely used as part of a clinical assessment, the DSM SUD Checklist also has utility for SUD screening research. One example is that the DSM SUD Checklist, specifically for opioid use disorder, was used to track symptoms associated with buprenorphine use among patients in primary care. Another example is the use of the DSM SUD Checklist to assist with medication tapering among patients in outpatient settings. In a recent study with incarcerated women, ates of opioid use disorder were high when screened with the DSM-5 OUD Checklist with an average of 10.4 symptoms endorsed before incarceration, with most scoring in the severe range, which was considerably higher than non-incarcerated samples. While more commonly used as a clinical component of SUD assessment, the DSM SUD Checklist also has utility for screening among incarcerated women.

SUD Treatment and Interventions

As the population of incarcerated women has grown, so too has a movement for “gender responsive programs”, an umbrella term for services that “understand, recognize, and act upon the unique circumstances that bring many girls and women into the criminal justice system”. Gender responsive programs that target the needs of women with SUD remain limited compared to programming for men. The approaches often used are typically “one size fits all” for justice-involved populations and do not embrace women’s relational issues and experiences associated physical and mental health, trauma and victimization, and parenting. In general, evidence-based SUD treatment approaches in the justice system have focused on (1) therapeutic communities to reinforce positive social learning, (2) medications to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders, and (3) behavioral interventions (such as cognitive-behavioral therapies) which focus on coping and decision-making. This section will overview selected literature on utilization of each of these approaches with incarcerated women.

A well-established form of SUD treatment for incarcerated individuals is the therapeutic community (TC). In general, therapeutic communities are grounded in social learning and modeling which is addressed using confrontational groups, strict enforcement of specific rules, job functions, and other restrictions. A specific goal of TC treatment is drugs and/or alcohol abstinence, as well as prosocial behaviors and attitudes, and TC models can be effective with both men and women in correctional settings. For women in particular, TC programs that incorporate a focus on mental health have also demonstrated significant reductions in substance use, commission of crimes, and improvements in mental health and trauma symptoms following release.

A more recent shift in corrections-based programming includes the use of medications to treat opioid use disorders (MOUD). While research on MOUD among justice-involved populations has grown in recent years with rigorously designed, controlled clinical trials of buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone, the majority of MOUD studies in corrections include predominantly incarcerated men or men under community supervision, and some do not include women at all. Specifically, Moore et al found that in a review on all three forms of FDA-approved OUD medications in jails and prisons found that studies ranged from 60% to 100% male samples, and only one study included only incarcerated women. In addition, most studies examining the effectiveness of MOUD in correctional settings have taken place in prison, with the few jail-based studies taking place in large urban areas. Research is needed on factors associated with MOUD utilization among incarcerated women, both during custody and upon community re-entry. In addition, while most research on medications in justice-settings focus on OUD, naltrexone has shown efficacy for alcohol use disorder treatment – yet research with justice involved women is very limited. Medications to treat other SUDs are not currently FDA approved. Given the constellation of interrelated issues faced by justice-involved women with SUD, it is also crucial that medications not just be offered in isolation, but in conjunction with other available social/behavioral SUD services, an additional area for future research.

In general, SUD treatment approaches for justice-involved women that integrate trauma-informed interventions have demonstrated positive outcomes. One auspicious example of cognitive behavioral therapy for incarcerated women with SUD is Seeking Safety, a co-occurring SUD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) therapy which utilizes psychoeducation and coping skills. Seeking Safety has been used as an enhancement to prison-based SUD treatment and shown to reduce symptoms of PTSD and other mental health issues among women with SUD over time. While outcomes of studies implementing Seeking Safety have been promising, additional research is needed specifically in conjunction with SUD treatment for women to further verify effectiveness. Other examples of interventions using cognitive behavioral approaches in the co-treatment of SUD and violence include Helping Women Recover and Beyond Trauma. These findings suggest that the co-treatment of trauma and SUD is critical for incarcerated women.

A more recently developing body of cognitive interventions for women include mindfulness, an approach focused on skill building to be more aware of one’s experiences to create an open, accepting, and non-reactive awareness. Mindfulness-based interventions have shown promise in the reduction of mental health symptoms among incarcerated women and women in residential SUD treatment programs.

Regardless of the specific treatment approach, carceral settings provide a critical timepoint to offer programs that address women’s interrelated needs of substance use and criminal activity. Gender-responsive programs, in principle, should address women’s specific needs, including substance use, mental health, trauma, significant relationships, as well as self-sufficiency. However, these treatment opportunities may be limited in corrections since they can be costly and burdensome to implement, requiring more time and energy from staff, both in training and service delivery. Thus, despite SUD and co-occurring issues among incarcerated women, treatment opportunities, particularly with a gender-responsive framework, are too often limited.

Referrals and Linkages to Community Care for Women After Release

Due to the limited corrections-based SUD treatment availability for women, referrals are often made to community “aftercare” programs following release from custody. Community treatment programs should employ “wraparound services” or a “continuum of care” from the correctional setting to the community to ensure that women’s often-interrelated issues are “simultaneously and successively” addressed, to promote a sense of safety, connection, and empowerment. A specific goal is to provide linkages to community resources to maintain long term therapeutic relationships to support SUD recovery. The chronic nature of substance use underscores the on-going need for continuity of care for individuals reentering the community following incarceration. While substance use problem severity is broadly linked to recidivism, relapse to substance use during community reentry is highly related to an increased likelihood of overdose. Women re-entering the community following jail or prison release are more vulnerable to overdose during the reentry period than men or women in the general population. Risk of relapse during the reentry period and the associated overdose risk may be further complicated by the vulnerabilities experienced by women both before, and following incarceration (eg, mental health problems, parenting-related stress, and history of victimization). These vulnerabilities are an important consideration when connecting women to community care, and interventions that address these needs holistically are critical in ensuring positive reentry outcomes for women, including risk reduction of relapse and/or overdose.

To more fully address the needs of women with SUD, studies have pointed to the role of community recovery support services during re-entry in achieving positive behavior change, as these services can improve access to needed social and environmental supports. For those reentering the community following incarceration, peer support specialists appear to be especially beneficial because of their lived experiences with navigating the challenges of reintegrating into society following incarceration, including understanding the demands for those with community correction requirements. Furthermore, peer support specialists serve as a source of accountability during reentry while also providing clients support in addressing basic needs such as employment, transportation, and housing. Heidemann et al examined support sources for formerly incarcerated women and reported that support from “others” (peers, agency staff, other professionals) significantly predicted women’s life satisfaction, as opposed to friends/family. These findings have been echoed elsewhere, with peer support specialists recognizing their role in linkages to care for women at community re-entry.

Peers may be one component of an integral stable social support network for women during community reentry. Strengthening women’s positive support networks (family, partners) has increasingly become a focus of many reentry programs. For women who use drugs, establishing new, non-drug using social network may aid in sustaining recovery, and thus, improve the likelihood of positive reentry outcomes. Parole officers can also play an important supportive role to women at reentry, as can other strategies such as case management, medical management, motivation-based interventions, peer navigation or some combination thereof. Much like the broader treatment literature, few re-entry programs have been designed for women, including those focusing on SUD. In a scoping review of substance use service linkage interventions for individuals reentering the community from jail, Grella et al found that only 2 of the 14 included women-specific components, which is clearly a critical area of needed future research.

Conclusions and Implications

In conclusion, this review indicates that there is a disproportionate representation of women with SUD in the criminal justice system in the US, and they have a number of unique issues related to SUD treatment engagement and retention. As the numbers of incarcerated women have continued to rise in recent years, SUD screening and treatment opportunities need to be standardized and expanded in both carceral settings and during community re-entry. In the absence of consistent and standardized evidence-based SUD screening and assessment tools, women who may benefit from services may pass through the justice system unrecognized, missing a critical opportunity for intervention. If implemented on a broad scale, screening tools may be effective in identifying more women with service needs during incarceration.

Also, gender-responsive treatment approaches are often limited in corrections, oftentimes because the number of women is smaller. Increasing opportunities for treatment for justice-involved women is important, but must be done with an eye to meeting specific needs which may vary by demographics (race/ethnicity, living environment, sexual orientation/gender identity), and mental and physical health issues including anxiety, depression, and PTSD related to violence and victimization histories. It is also noteworthy that most incarcerated women have children, and SUD treatment must incorporate a focus on issues associated with reunification with their children, efforts to increase parenting skills, and providing support for children. Women’s success in SUD treatment depends on addressing these needs to support treatment success.

Incarceration and community re-entry are stressful, and being attentive to women’s needs associated with their families, relationships, and social networks is critical to success. Given that women’s patterns of substance use, periods of abstinence, and occurrences of relapse are closely tied to their intimate partner relationships, it is also important that corrections-based treatment provides an emphasis on social relationships and connectedness following release. In addition to programs during custody, there is a need for community re-entry planning and “warm-handoff” to community-based services for all women following release, but particularly important for women returning to rural communities with limited service availability.

We recognize that this review is limited to US studies with justice-involved women, which may limit generalizability of findings to women with SUD incarcerated in other countries. While beyond the scope of work for this review, attention to variations in criminal justice systems and the nature of SUD programming in other countries should be considered in future research. This review has important implications for US correctional policies to continue to support and expand evidence-based practices along the cascade of care continuum. Attrition can occur during each phase from engagement to retention, and it is vital that correctional contexts support successful progression through each phase to support positive recovery outcomes. With an increase in treatment availability and access, there should also be a focus among correctional and community treatment leadership on stigma reduction when women re-enter the community including education, referrals to an array of service providers, and family-supportive services and resources.

There are also implications for expanding corrections-based MOUD treatment for women. Studies have shown benefits of MOUD initiation during custody including significant (85%) reductions in drug-related overdose in the month after prison release and reductions in recidivism. However, MOUD remains widely underutilized in correction settings, particularly for women. Implications for research include increasing our understanding of MOUD use among women, advancing research on medications to treat other SUDs, short and long-term MOUD outcomes in custody and during community transition, and necessary wraparound services to increase the likelihood of MOUD retention.

Other implications of this review include the need for expanded access to supportive recovery resources during community re-entry to prevent relapse and overdose. Relapse after incarceration-induced abstinence is associated with an exponential increase in overdose fatality. Because women with SUD experience unique structural and social vulnerabilities that impact both relapse and overdose risk (eg, drug-involved romantic relationships, interpersonal violence, lifetime adverse experiences, poor mental health, parenting-related stress, and unequal gendered power dynamics) interventions that address these types of underlying factors are critical in having a long-term, sustainable impact on successful recovery among women.