Abstract

We examined the developmental and situation-specific differences between four groupings of adolescents charged with a first offense: those who committed the crime and told the authorities they committed the crime (true confessors; 71%), those who committed the crime but told the authorities they did not commit the crime (false deniers; 8%), those who did not commit the crime but told the authorities they did commit the crime (false confessors; 12%) and those who did not commit the crime and told the authorities they did not commit the crime (true deniers; 10%). Findings indicate a developmental profile for each respondent grouping, and an overall effect in which adolescents with lower psychosocial maturity tended to have higher perceptions of the legitimacy and fairness of legal authorities. These results suggest that psychosocial maturity is an important factor to bear in mind even from the first legal interactions with officers of the justice system.

Legal interactions with officers of the justice system can be a daunting experience for adolescents who are suspected of committing a crime. During these interactions, justice authorities, such as law enforcement, probation officers, and judges, attempt to piece together what truly occurred during a suspected crime using data available from different sources, including adolescents’ own testimonies. From the adolescents’ perspective, there may be a tension, and even confusion, in navigating whether to speak the truth and risk the consequences (including not being believed), or to tell a lie to protect themselves or another individual, given typical societal values for honesty (Bok, 1978), but also a societal, and indeed developmental, proclivity toward lying for personal gain, to avoid consequences, and protect oneself and others (DePaulo et al., 1996; Steingrimsdottir et al., 2007; Warr, 2007).

We know very little about the characteristics of adolescents who are likely to be forthcoming versus deceptive about minor offenses with which they have been charged. Yet, both their individual characteristics as well as the situational characteristics of their putative offenses are likely related to the way that they engage with the legal system in terms of how they share their account of the offense. In this study, we examine the relation between developmental characteristics, situational specifics (i.e., type of offense being processed), and the legal interactions of adolescents involved with the juvenile justice system due to an arrest for a first offense.

Concealment and Disclosures

Even though the majority of adolescents conceal information from parents at times (Darling et al., 2006; Lavoie & Talwar, 2022), many endorse sharing and providing information in a forthcoming manner (Cumsille et al., 2010; Smetana et al., 2006). There are specific types of information that adolescents are more likely to conceal, specifically from parents, such as issues they believe are their own, or their friends’, personal matters (Smetana et al., 2006). Adolescents are also likely to hide from parents their pastimes that involve illegal activities (Frijns et al., 2010; Keijsers, 2016; Keijsers et al., 2010; Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Tilton-Weaver, 2014), which can be out of fear of parents’ disapproval and potential resulting consequences (Metzger et al., 2013; Smetana et al., 2009; Yau et al., 2009). For adolescents interacting with legal authorities for the first time, it is possible that they may carry the same behavioral responses of disclosure generally.

Disclosures to Legal Authorities

Adolescents’ interactions with an officer of the justice system are often characterized by high-pressure interrogations (Feld, 2006, 2013; Malloy et al., 2014). In the United States, suspects are typically presumed guilty (Redlich, 2010), and for adolescent suspects, this presumption affects how they are interviewed (Redlich & Kassin, 2009). For example, in a sample of police interviews with adolescent suspects of crime in the USA, Feld (2006) found that police regularly included one or more maximization or minimization approaches (i.e., in brief, interrogation tactics that either overplay the severity of the crime or evidence available in order to push a confession, or tactics that underplay the severity or provide moral justification in order to make the suspect feel secure to confess; outlined in-depth in Inbau et al., 1986). In fact, responses from a sample of law enforcement officers suggest that they do perceive that adolescents can be interrogated in the same way as adults (Meyer & Reppucci, 2007). Further, Cleary and Warner (2016) found that police officers in the United States do interrogate adolescent suspects in the same way as adult suspects, despite their differing developmental needs and status as minors. Overall, these findings raise questions about how such interactions might impact adolescents’ tendencies to be truthful and forthcoming with police officers.

During interactions with police officers, adolescents may confess or deny (truthfully or falsely) participation in illegal activity. Previous studies have found some individual differences in how adolescents respond. For example, being of a younger age (i.e., adolescence) and male are associated with a higher likelihood of making a false confession during a police interrogation (Gudjonsson et al., 2016). Further, substance abuse, a history of being bullied or experiencing violence, having committed a crime of burglary, and, for boys, a history of extra-familial sexual abuse are all associated with a higher likelihood of making a false confession (Gudjonsson et al., 2009). The results of one study speak to the possible motivations for which adolescents may give a false confession. Specifically, the results of a study with Danish college-age students (M = 19 years, range 16–25 years) who had been interrogated or questioned by police about a suspected offense, indicated that the primary reason they provided a true confession was to be able to leave the police station or because they believed that the police had evidence of their involvement (Steingrimsdottir et al., 2007). These findings highlight some important developmental considerations, in particular that adolescents may say what they feel they need to, in part driven by a desire to avoid any immediate discomfort, despite potential future consequences, as well as a higher potential for being vulnerable to suggestible or leading interrogation techniques (e.g., as outlined in Scott-Hayward, 2007) Overall, these findings outlined in this section suggest that adolescents’ disclosures to legal authorities are likely influenced by feelings of pressure, potentially shifting their typical disclosure tendencies away from what they might typically be to other forms of authority.

Psychosocial Maturity and Disclosures

One of the reasons why adolescents highly endorse disclosures overall (Cumsille et al., 2010) may be because there is a social benefit to being truthful and forthcoming (Levine et al., 1999). Consequently, adolescents with greater maturity and psychosocial skills that facilitate open communication may also be more forthcoming. At the same time, in the context of a legal disclosure of wrongdoing, the consequences to truthfully disclosing guilt are high and likely to influence adolescents’ futures, which adolescents tend to underestimate relative to adults (Redlich & Shteynberg, 2016).

Psychosocial maturity can be understood as a combination of three key factors: temperance, perspective, and responsibility (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000). Temperance refers to the ability to control impulses and suppress aggressive responses, perspective encompasses empathic understanding of others and future-oriented thinking, and responsibility captures a sense of personal responsibility and ability to make decisions independent of peer influences (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000; Steinberg & Cauffman, 1996). Psychosocial maturity tends to increase with age (Icenogle et al., 2019) and is associated with less antisocial decision-making (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000), and desistance from engaging in illegal activity (Monahan et al., 2009). Cognitive ability, including decision-making and reasoning, and psychosocial capability, including self-restraint, are both important abilities in legal decision-making (Steinberg & Icenogle, 2019). In fact, in a seminal work, Grisso (1989) argued that even simply age and IQ (potentially both as proxies, or correlated to aspects of psychosocial maturity, but not completely overlapping) were important factors in determining whether an adolescent could be considered competent for the purposes of legal-decision-making, for example waiving his or her rights. Considering the above findings, psychosocial maturity may also be associated with adolescents’ initial likelihood of disclosing information about illegal activities.

Disclosures and Perceptions of Procedural Justice

Perceptions of what will occur after one discloses help to determine whether to share information. According to the social information processing theory (Crick & Dodge, 1994), social cues about the acceptability of a behavior are retained and are key in processing how to behave in future similar situations. Based on this model of processing, adolescents who have disclosed sensitive information and have had a negative response–for example, being punished for the activity they disclosed–may be hesitant to disclose in the future. Adolescents who have been detained for committing a first offense may not have prior experience that determines whether or not they share information. However, preconceived thoughts about the fairness and legitimacy of legal actors (Tyler, 1990), and about the validity of the legal system may influence willingness to disclose versus conceal details of their illegal activities. In fact, the result of a systematic review of youth contact with legal authorities suggests that increased contact with legal authorities is associated, and perhaps even leads to, poorer perceptions of the law and legal authorities (Massez et al., 2023; see also Del Toro et al., 2019). Youths’ perceptions of police legitimacy, for instance, derive from believing the authority treats individuals fairly and justly (Fine & Tom, 2023; Tyler & Trinkner, 2018). When adolescents perceive legal authorities to be fair and legitimate sources of authority, there is a strong foundation to the relationship that may facilitate cooperation (Hamm et al., 2017; Hinds, 2007; Bolger & Walters, 2019). As part of this, adolescents may be more likely to be forthcoming. Further, because youth who report higher levels of legal cynicism typically reject the social norms foundational to the law (Sampson & Bartusch, 1999), legal cynicism may differentiate willingness to report truthfully to legal authorities.

Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to explore differences in age and psychosocial maturity of adolescents who truthfully versus falsely communicated about their guilt to justice system personnel. We also assessed whether the type of offense (i.e., violent or non-violent) was associated with adolescents’ truthful versus deceptive responses, given that motivations to conceal could be higher among adolescents who were charged with a violent offense due to potentially more severe consequences (a strong motivator for lying, e.g., Talwar and Lee, 2011). Finally, we compared adolescents’ perceptions of police legitimacy and legal cynicism to determine whether adolescents were more likely to be forthcoming with legal authorities when they perceived them to be fair and legitimate as sources of authority.

We expected that adolescents who truthfully admitted to committing a crime would be young, immature, and perceive police as more legitimate, based on the social value and acceptability of being honest (e.g., Levine et al., 1999). We anticipated that adolescents who truthfully denied committing a crime would have relatively high psychosocial maturity as well as positive perceptions of police as legal authorities for the same reasons; that is, they would feel safe to tell the truth and deny involvement, anticipating a fair response. We expected that adolescents who falsely denied committing a crime would be more mature and more likely to perceive police negatively, using a false denial to protect themselves from consequences (e.g., Gudjonsson et al., 2004). Finally, we expected that adolescents who provided a false admission of guilt would be relatively lower in psychosocial maturity and more likely to perceive police legitimacy negatively (e.g., Cauffman et al., 2010; Cleary, 2014).

Method

Participants

Participants were 1,216 adolescent males ages 13–18 years old charged with a first-time offense of moderate severity. Approximately 77.81% of the sample (N = 947; M = 15.30 years, SD = 1.29 years) youth had complete data on the key study measures, with no significant differences between the included and excluded samples on key measures (see “Missing data” section below). Participants were part of the first wave of the Crossroads Study (Cauffman et al., 2020), which is a longitudinal study of adolescent males in three states (Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and California) who had committed a first offense at the point of contact for the research study (see https://sites.uci.edu/crossroadsinfo/). Adolescents self-identified as Latino (46%), Black (38%), White (14%), and other (2%). Approximately 84% of offenses were non-violent in nature (i.e., there was no intent to harm another individual and there was no assault or attack on another individual, as defined by the US Department of Justice, 2004), and included offenses such as possession, use of marijuana, theft, and vandalism.

Measures

IQ

Participants completed two subtests of the Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) to generate an approximate value for their intelligence quotient (IQ), which was included as a control measure. The Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests were used, and participant’s scores were normed and standardized.

Psychosocial Maturity

Psychosocial maturity was assessed as a combination of temperance, perspective, and responsibility (Steinberg & Cauffman, 1996). Sores were a combined mean of the z-scores on six measures, consistent with previous research (e.g., Fine et al., 2018; Monahan et al., 2013), specifically the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (Greenberger et al., 1975); the Future Outlook Inventory (Cauffman & Woolard, 1999), the Resistance to Peer Influence 10-item questionnaire (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007); and the Impulse Control, Suppression of Aggression, and Consideration of Others subscales in the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (Weinberger & Schwartz, 1990).Each of the measures assessed an aspect of psychosocial maturity and were standardized and combined to index the construct. Temperance was assessed using the Impulse Control and Suppression of Aggression subscales in the Weinberger; perspective was assessed using the Consideration of Others subscale in the Weinberger and the Future Outlook Inventory; and responsibility was assessed using the Resistance to Peer Influence and Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (measuring personal responsibility). Scores ranged from − 1.76 to 1.68 (M = 0.00, SD = 0.59), and higher scores represent higher psychosocial maturity.

Legal Sanctions

Participants were asked a series of questions about their legal history and about the offense for which they were being charged. Questions were developed for the Crossroads study, based on previous measures as well as a literature review of relevant factors to consider regarding legal sanctions. Specific questions relevant for this analysis included (1) whether they had committed the offense for which they were being charged (“Did you do the offense that you were charged with?”), and (2) what they had told an officer of the justice system regarding their involvement (“Did you admit (plead guilty) to any of the charges?”). Responses included “yes”, “no”, “sort of”, “don’t know”, or “not applicable (i.e., adolescent had not gone to court yet). Adolescents who responded “sort of” (n = 130) or “don’t know” (n = 1) in response to “did you do the offense that you were charged with,” and adolescents who responded “not applicable – hasn’t gone to court yet” (n = 155) or “don’t know” (n = 8) in response to “did you admit (plead guilty) to any of the charges?” were ineligible for inclusion in analyses due to the uncertainty of their responses as we were not able to confidently put them into respondent groups based on their answers.

Police Legitimacy

Tyler’s four-item scale (Tyler, 2006) was used to assess youths’ perceptions of police legitimacy. Using a 4-point Likert (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree), youth responded to four items: “I have a great deal of respect for the police”; “Overall, the police are honest”; “I feel proud of the police”; and “I feel people should support the police.” Higher mean values indicated more positive perceptions of police legitimacy (M = 2.35, SD = 0.83, range = 1–4, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86).

Legal Cynicism

Youths’ legal cynicism was assessed using Sampson and Bartusch’s (1999) five-item scale. Items reflected an agreement that it was acceptable to behave outside of the norms of society and the law, for example “Laws were made to be broken” and “It’s okay to do anything you want as long as you don’t hurt anyone,” rated on a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). Higher mean scores indicated more cynicism (M = 2.04, SD = 0.57, range 1–4, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63).

Procedure

Ethics Approval was obtained from each of the three university sites. Participation involved meeting with a research assistant within six weeks of the offense disposition to complete a face-to-face and screen-facilitated interview. Adolescent’s parents or guardians provided consent and adolescents gave assent to participate. To encourage honest reporting, youth were informed they could skip any question they desired. Participants’ responses were protected by a Privacy Certificate from the Department of Justice, and participants were given a detailed explanation about the Privacy Certificate and how it protected their responses from involuntary disclosures (e.g., court subpoenas). This explanation was also repeated before sensitive questions. Participants were able to enter their own responses so that the researcher would not see how they responded, to encourage forthcoming responses.

Coding

Adolescents were grouped on two dimensions: (a) whether they actually committed the crime, as self-reported to study personnel; and (b) whether they told an officer of the justice system that they committed the crime. There were four groups: true confessors, who did the crime and said they did the crime; false confessors, who did not do the crime, but said they did; true deniers, who did not do the crime and said they did not; and false deniers, who did the crime, but said they did not.

Analytic Approach

We tested for age differences according to respondent type using multivariate multinomial logistic regression models to allow for robust statistical testing of the associations between multiple predictor variables and our multi-category outcome variable (respondent groups, n = 4). We then tested for global psychosocial maturity differences, controlling for age and IQ, using multinomial regression models. Finally, we analyzed respondents’ perspectives of the validity of procedural justice, as well as the severity of offenses according to respondent grouping, using multinomial regression models.

Results

Missing Data

Approximately 77.81% of the sample (N = 947) youth had complete data on the key study measures. There were no differences by age (p = .66), police legitimacy (p = .07), psychosocial maturity (p = .90), or cynicism (p = .62). Youth with complete data had slightly lower IQs (diff = 2.52, 95% CI = 0.39, 4.64, SE = 1.08, p = .02). Altogether, the missing data patterns indicated that missingness was not systematically related to variables of interest and was not likely to impact results. The sample of youth with complete data on several of the sub-analyses was slightly higher (between 1 and 4 participants more), as such, we have included those additional participants in sub-analyses.

Respondent Type

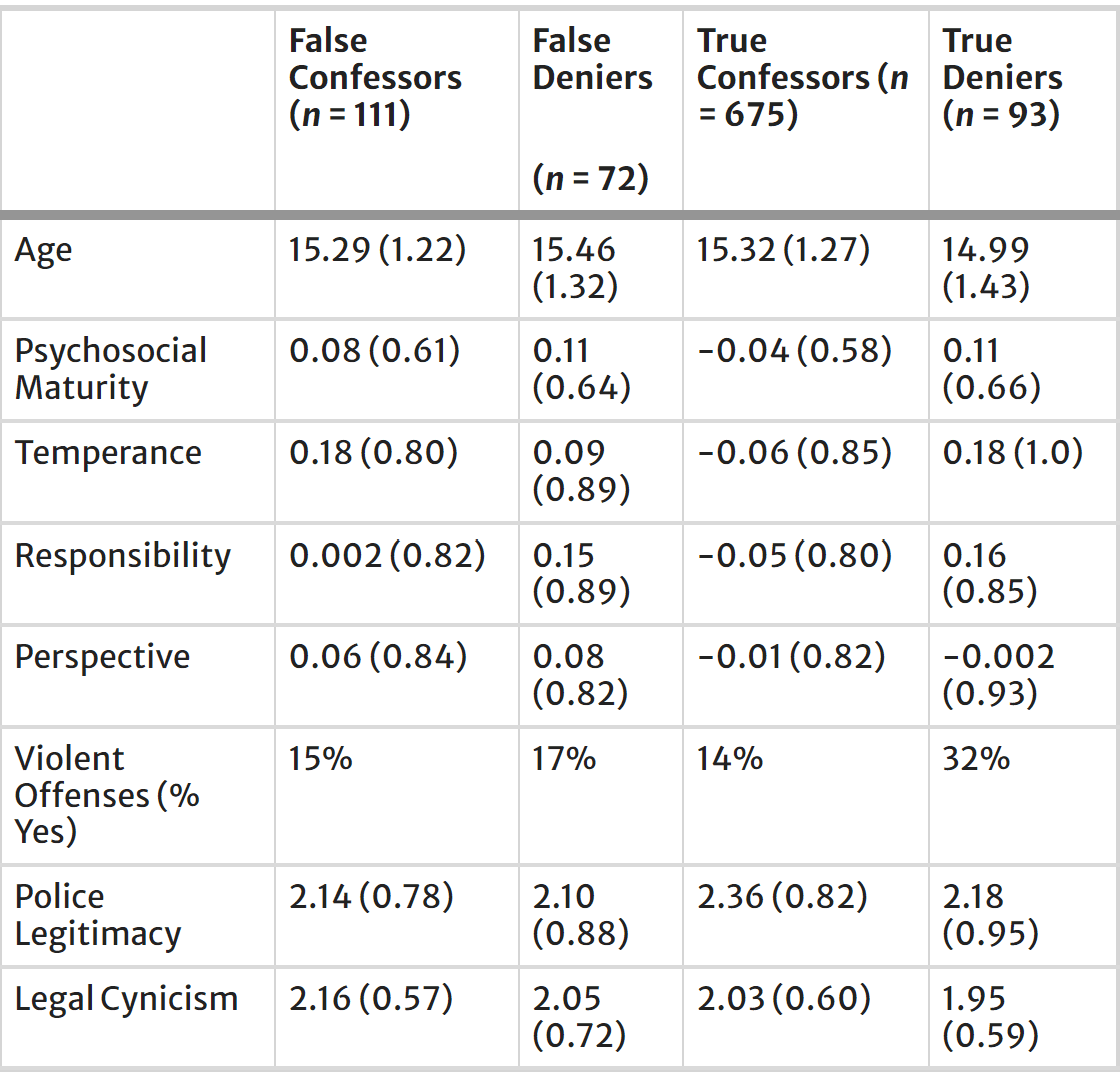

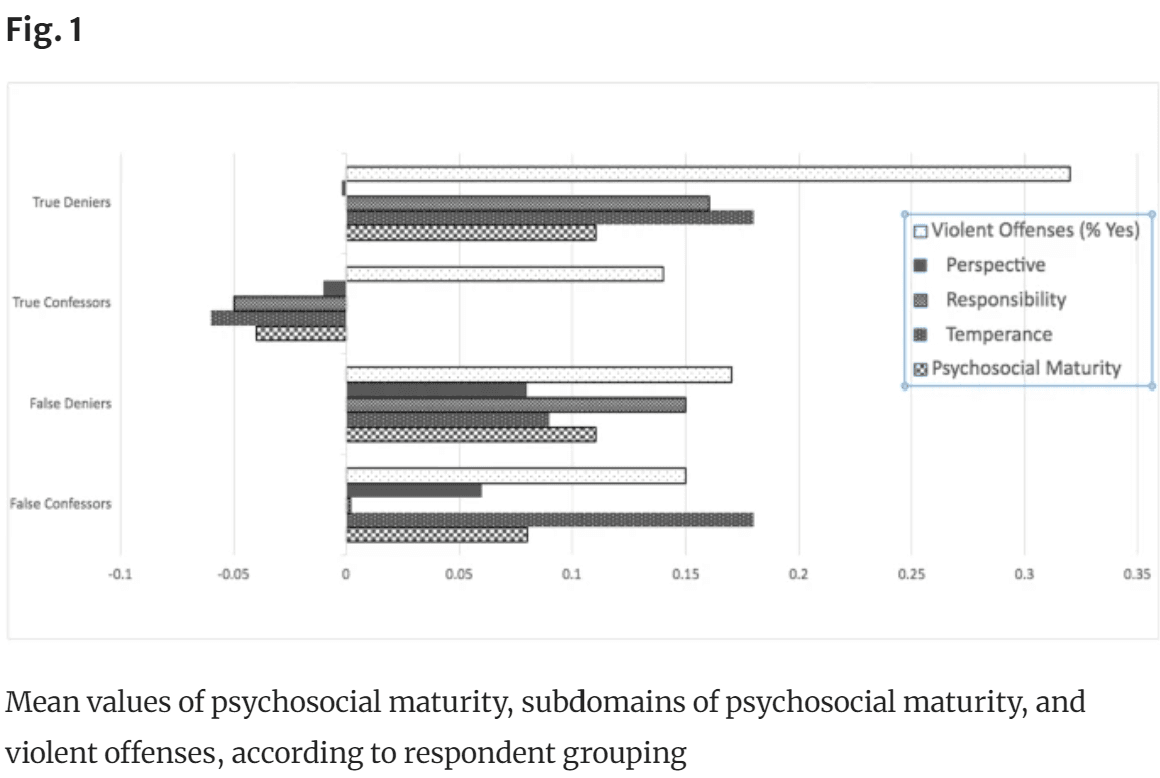

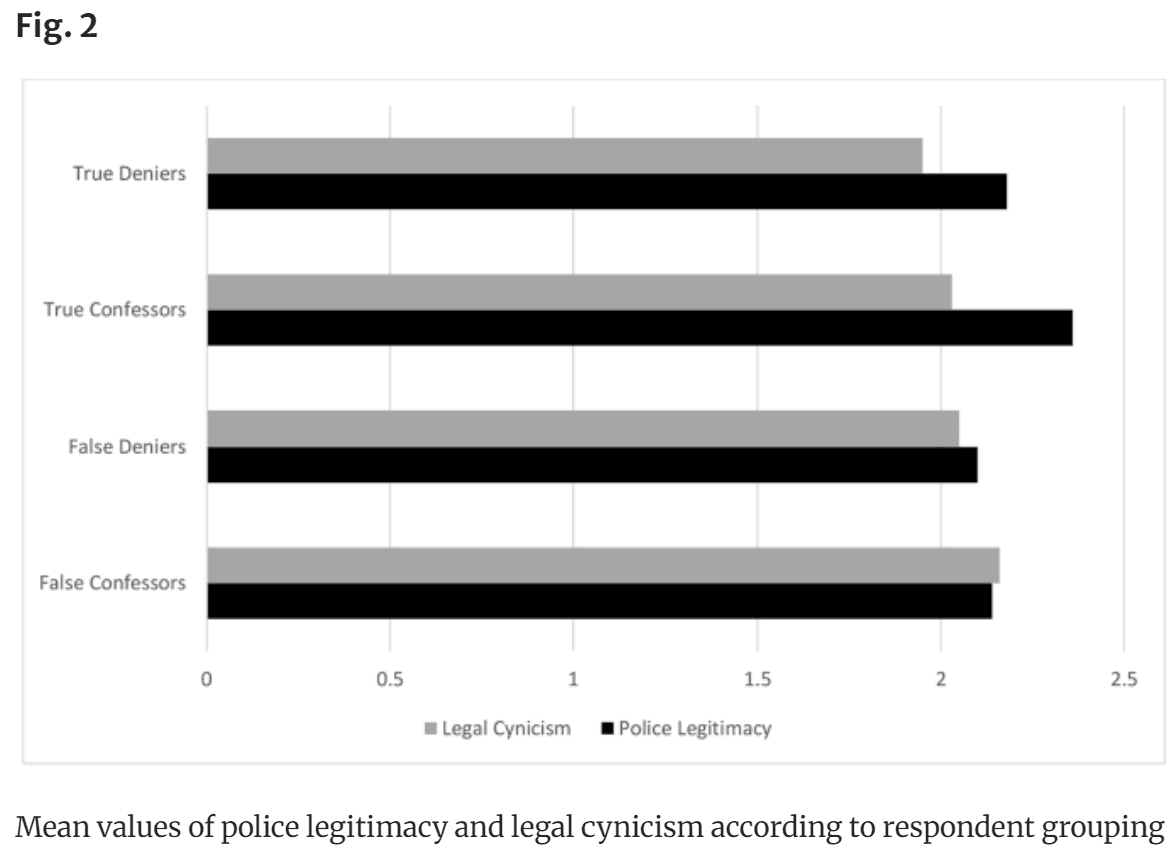

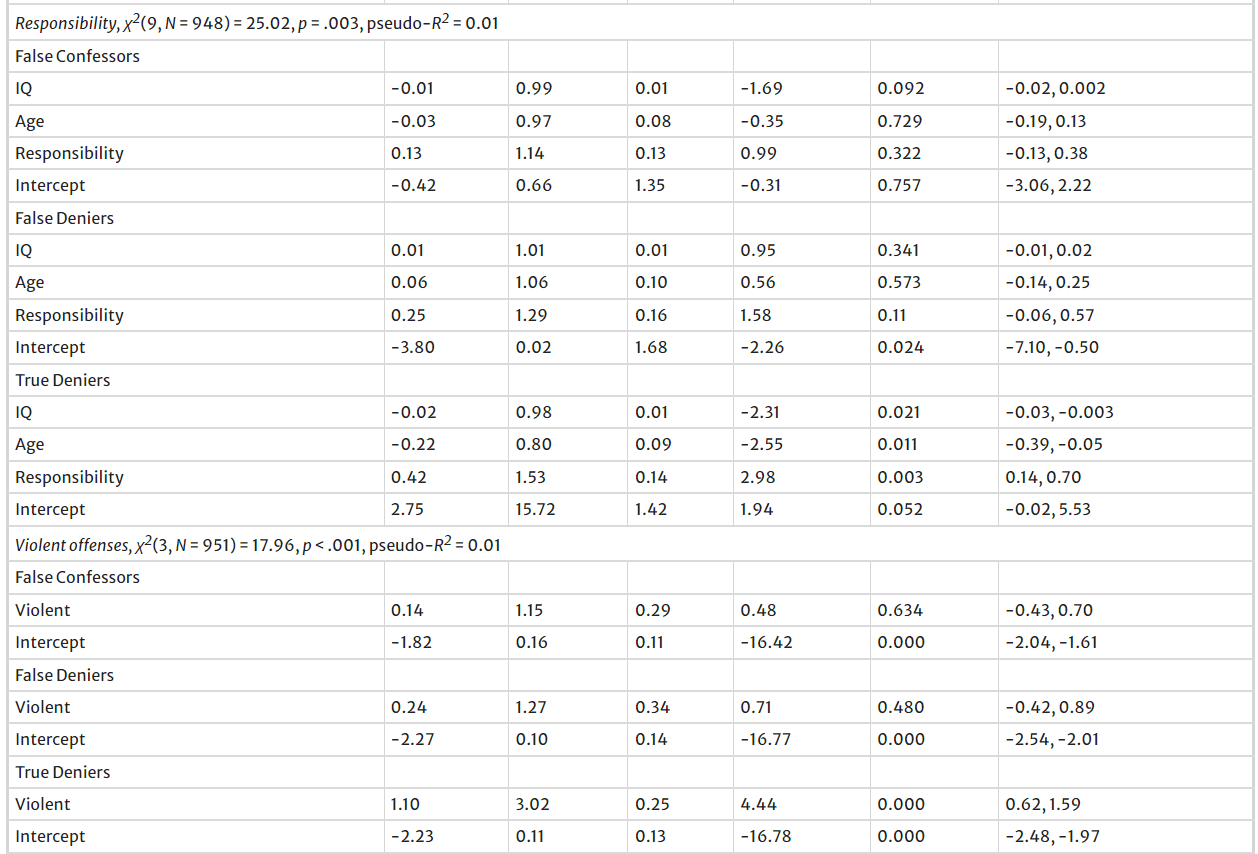

The majority of adolescents were true confessors (n = 675; 71%), followed by false confessors (n = 111; 12%), true deniers (n = 93; 10%), and false deniers (n = 72; 8%; combined percentages exceed 100 due to rounding). Table 1 contains descriptive information and Figs. 1 and 2 contain a visual depiction on each of our key measures.

Test of Potential Covariates

IQ differed between the types of respondents, based on a multinomial logistic regression that tested the association between IQ and respondent type, χ2(3, N = 950) = 8.92, p = .030, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. Specifically, false deniers (M = 87.29, SD = 17.0) had higher IQ scores than false confessors (M = 81.88, SD = 15.38), p = .021, and true deniers (M = 81.47, SD = 16.28), p = .017. There were no IQ differences between true confessors (M = 84.68, SD = 15.15) and any of the other three groups.

We also tested for age differences between the types of respondents using a multinomial regression, controlling for IQ, and found significant differences in age across respondent groups, χ2(6, N = 950) = 14.93, p = .021, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. We found that true confessors (M = 15.32 years, SD = 1.27 years) were significantly older than true deniers (M = 14.99, SD = 1.43), p = .025, and that false deniers (M = 15.46, SD = 1.32) were significantly older than true deniers, p = .032. As a result of these analyses, age and IQ were controlled in all subsequent analyses.

We further tested for race differences between the types of respondents using multinomial regression and found no significant differences, χ2(3, N = 951) = 5.55, p = .136, pseudo-R2 = 0.00. Consequently, race was not considered further in analyses.

Psychosocial Maturity

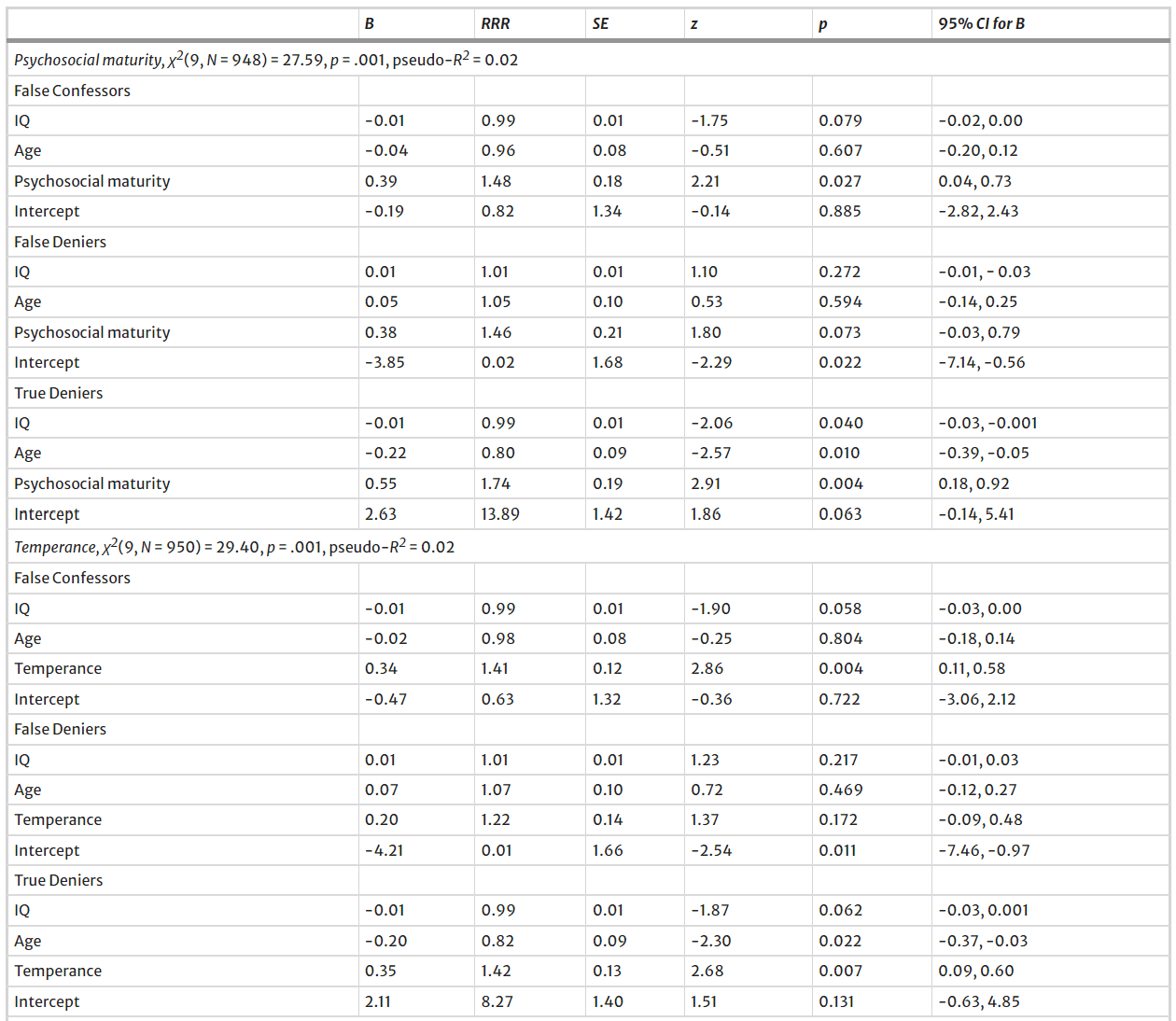

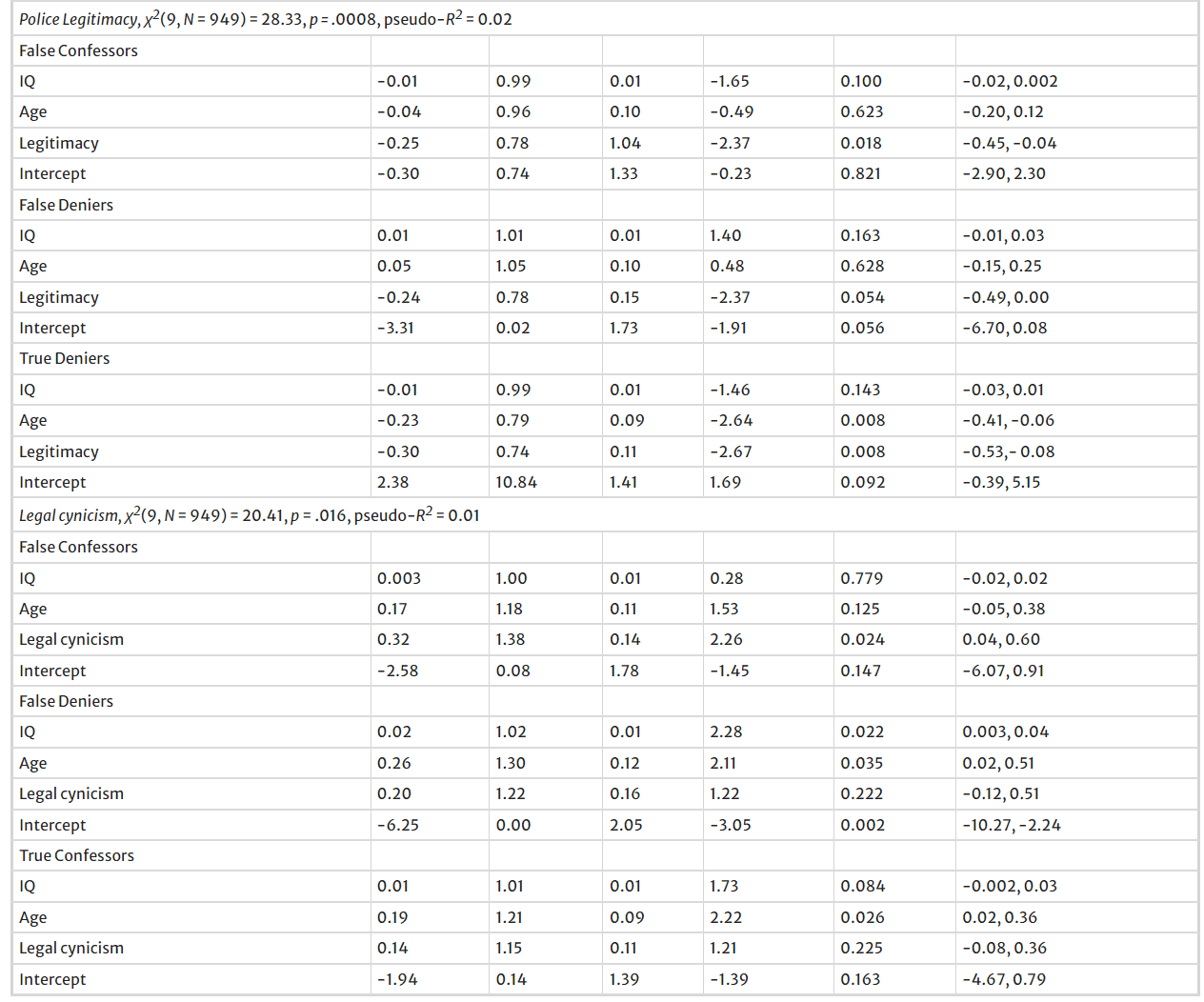

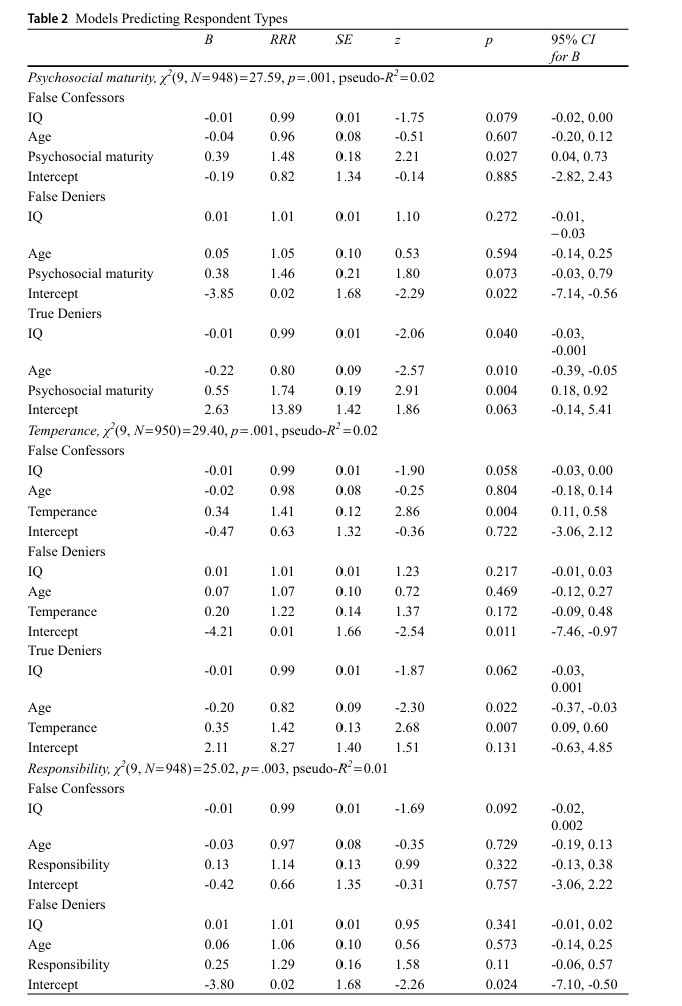

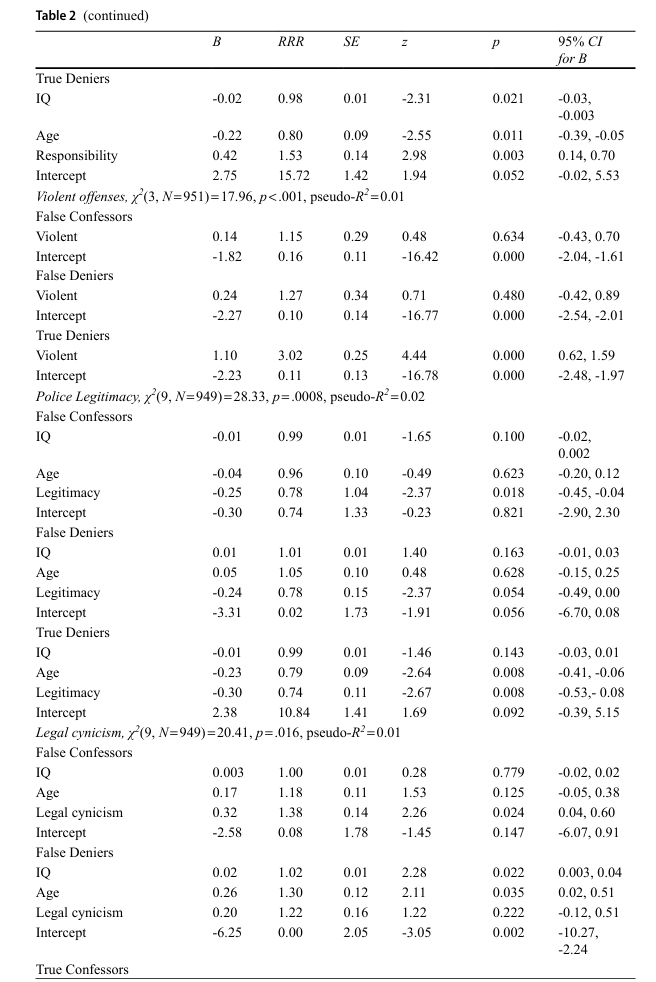

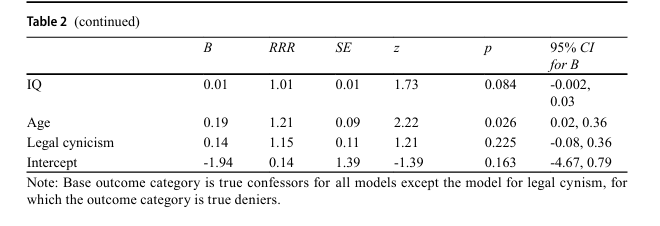

We used a multinomial regression to examine whether differences in psychosocial maturity would emerge between the types of respondents, while also accounting for age and IQ. The model was significant, χ2(9, N = 948) = 27.59, p = .001, pseudo-R2 = 0.02. In comparison to true confessors (M = -0.04, SD = 0.58), false confessors (M = 0.08, SD = 0.61) and true deniers (M = 0.11, SD = 0.66) had higher psychosocial maturity, p = .027 and p = .004 respectively. Table 2 contains model details for this model and models reported below.

We also tested for differences across the three domains of psychosocial maturity, specifically temperance, perspective, and responsibility, using a multinomial regression, while accounting for age and IQ. Regarding temperance, the overall model was significant, χ2(9, N = 950) = 29.40, p = .001, pseudo-R2 = 0.02. Both false confessors (M = 0.18, SD = 0.80) and true deniers (M = 0.18, SD = 1.0) had higher temperance scores than true confessors (M= -0.06, SD = 0.85), p = .004 and p = .007 respectively. We also conducted the model with perspective, but the model was not significant, χ2(9, N = 950) = 16.21, p = .063, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. The model with responsibility was significant, χ2(9, N = 948) = 25.02, p = .003, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. True deniers (M = -0.002, SD = 0.93) had higher responsibility scores than true confessors (M = -0.01, SD = 0.82), p = .003.

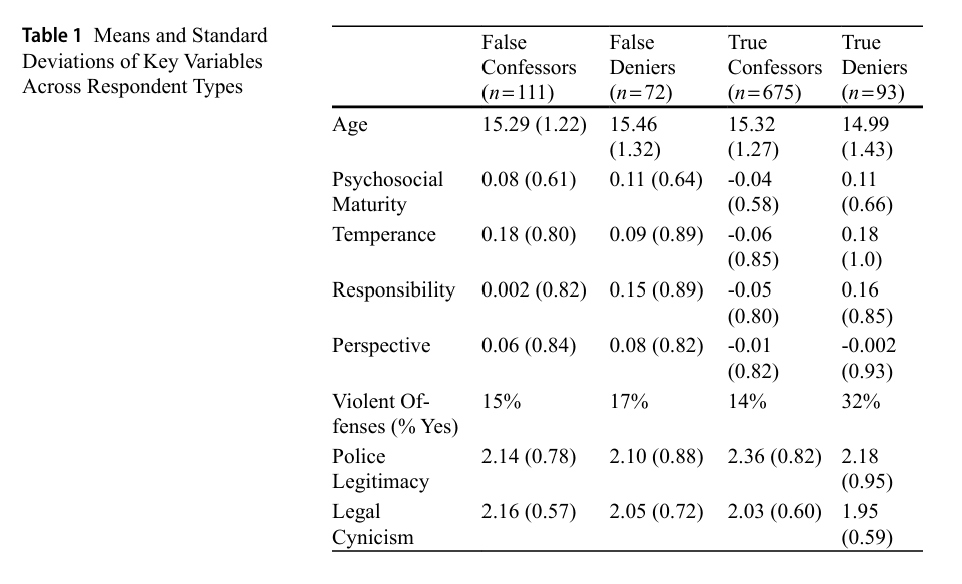

Perceptions of Police Legitimacy and Legal Cynicism

We used a multinomial regression to compare differences in adolescents’ perceptions of police legitimacy or legal cynicism according to respondent type, and accounting for age and IQ. The model assessing perceptions of police legitimacy was significant, χ2(9, N = 949) = 28.33, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = 0.02. Significant differences were found between true confessors and false confessors, as well as between true confessors and true deniers. True confessors (M = 2.39, SD = 0.82) perceived police as more legitimate than did false confessors (M = 2.18, SD = 0.82), p = .018. In other words, youth who falsely admitted to committing the crime reported worse perceptions of police legitimacy than did youth who admitted that they had committed the crime and had actually committed that crime. Further, true confessors perceived police as more legitimate than did true deniers (M = 2.16, SD = 0.89).There were significant differences in the perceived levels of legal cynicism according to respondent type, χ2(9, N = 949) = 20.41, p = .016, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. False confessors (M = 2.15, SD = 0.57) had higher scores on legal cynicism than true deniers (M = 1.95, SD = 0.59), p = .024.

Violent Versus Non-Violent Offenses

As some of the adolescents’ offenses were violent in nature, we compared respondent types according to violent versus non-violent offenses using a multinomial regression. The overall model with violent versus non-violent offense as the predictor and respondent type as the outcome was significant, χ2(3, N = 951) = 17.96, p < .001, pseudo-R2 = 0.01. The group of true deniers (32% violent offenses) were overall more likely to have been adjudicated as delinquent for committing a violent offense than true confessors (14% violent offenses), p < .001. To determine if this difference in offending across groups might have influenced our other study results, we reran all analyses controlling for type of offense and there were no changes in any significant findings.

Discussion

Summary

Overall, the findings indicate that within this sample of male adolescents who were arrested for the first time and for an offense of moderate severity, the vast majority truthfully disclosed their involvement and guilt (approximately 71%; figure includes both true confessors and true deniers). There were also groups of adolescents who were not truthful about their alleged offences, again based on whether they had committee the offense, some of whom lied about committing a crime (false confessors) and others lied about not committing a crime (false deniers). Most importantly, given the relative strength of the findings, we found significant differences across these groups in terms of psychosocial maturity, with true confessors demonstrating the lowest psychosocial maturity of the four groups. We also found differences across the four groups in perceptions of police legitimacy, with true deniers and false confessors indicating a lower trust in legal authorities in general. Finally, true deniers were more likely to have been charged with a violent offense than true confessors.

True Confessors as Psychosocially Immature but Trusting Legal Authorities

True confessors were the most psychosocially immature (but not the youngest) of the four groups, and they perhaps lacked the psychosocial maturity to act differently. Given that confessing to a crime (truthful or not) is most always associated with being found guilty (e.g., Fisher and Rosen-Zvi, 2008; Kassin & Neuman, 1997), individuals are more likely to say the right approach is to remain silent (e.g., the young adult sample in Grisso et al., 2003). However, younger adolescents are more likely to believe that they will be treated well if they confess (Grisso et al., 2003), which is not generally the case (Redlich, Yan, Norris, & Bushway, 2018), perhaps because their parents have used the disciplinary approach that they will be more lenient with their child, and not punish them, if their child tells them the truth. For example, as one study found, adolescents do not generally endorse lying to conceal a misdeed from a parent (Perkins & Turiel, 2007). In sum, younger adolescents, in general, likely do not realize that their parents may not punish them if they tell the truth, but that legal authorities will not respond similarly.

Turning to the question of the role of psychosocial maturity in legal decision-making, psychosocial immaturity is characterized by a general tendency to underestimate the likelihood that there will be negative consequences for actions, as well as a tendency to focus more on the immediate risk or rewards of the moment while not thinking about how immediate decisions could impact the future (Steinberg & Cauffman, 1996). For adolescents involved in the justice system, some of the immediate rewards to confessing could have included pleasing the justice officer who was questioning them (given that social rewards are especially influential on adolescents; Foulkes and Blakemore, 2016) and ending the questioning (Scott-Hayward, 2007). In fact, given that true confessors’ offenses were more likely to be non-violent than true deniers’ offenses, it may be that true confessors were less aware of the severity of their crime and of the consequences of their actions. This last explanation is most in keeping with the finding that true confessors were fairly trusting of police legitimacy and legal authorities in general, and that they found police treatment toward them to be fair and legitimate.

Further complicating the matter, true confessors perhaps lacked the psychosocial maturity to act differently; given that confessing to a crime (truthful or not) is most always associated with being found guilty (e.g., Fisher and Rosen-Zvi, 2008; Kassin & Neuman, 1997), individuals are more likely to say the right approach is to remain silent (e.g., the young adult sample in Grisso et al., 2003). However, younger individuals are more likely to believe that they will be treated well if they confess (Grisso et al., 2003), which is not generally the case (Redlich et al., 2018), perhaps because their parents have used the disciplinary approach that they will be more lenient with their child, and not punish them, if their child tells them the truth. For example, as one study found, adolescents do not generally endorse lying to conceal a misdeed from a parent (Perkins & Turiel, 2007). In sum, younger adolescents, in general, likely do not realize that their parents may not punish them if they tell the truth, but that legal authorities will not respond similarly.

Previous studies can help to shed light on our finding that true confessors were both psychosocially immature and trusting of legal authorities. Immaturity is associated with decreased abilities in areas that are relevant for legal decision-making (Grisso et al., 2003), such as a higher sensitivity to short-term rewards and lower sensitivity to future consequences of their actions (Cauffman et al., 2010). In fact, judges rate age and maturity as being important factors in determining whether an adolescent is competent to stand trial (Cox et al., 2012), which highlights the need to consider, assess, and protect against the vulnerability of developmental immaturities related to legal-decision-making. Further, given that true confessors’ offenses were more likely to be non-violent than true deniers’ offenses, it may be that true confessors were less aware of the severity of their crime and of the consequences of their actions.

False Deniers as Intelligent and Trusting Legal Authorities

False deniers emerged as being relatively intelligent (in comparison with other respondent types), trusting of legal authorities in general and tending to report that police were legitimate and fair in their treatment toward them. False deniers were likely motivated to lie to avoid consequences (a strong motivator; Talwar and Lee, 2011). A previous study by Gudjonsson and colleagues (2004) found that, of college-age students (15–25 years old) who had been interrogated by police, 19% of them had provided a false denial of wrongdoing to the police. The authors found that both false denials and false confessions were associated with antisocial personality traits more broadly, which is in keeping with the developmental relation between antisocial behavior and lying more generally. For example, adolescents who are involved in illegal activities are perceived as being more deceptive (Keijsers et al., 2010; Warr, 2007), in particular toward parents (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Further, teacher and parent perceptions of more frequent lying among children longitudinally is associated with problematic behaviors (Gervais et al., 2000).

At the same time, despite the fact that within a developmental context, telling a lie to protect oneself is considered antisocial and concerning, within a legal context, telling a lie to a justice officer to conceal illegal behavior may actually reflect a calculated decision response that is not morally desirable, but that is practically sensible. In other words, it may be an intelligent decision for them to lie to conceal wrongdoing, reflecting the higher IQ of this respondent group, to avoid legal sanctions and the broader negative impact on their lives and future aspirations if having a juvenile criminal record.

Psychosocially Mature but Untrusting of Legal Authorities

Both true deniers and false confessors emerged as more psychosocially mature than true confessors, yet both respondent groups had lower perceptions of police authority legitimacy. True deniers in particular were the youngest of the groups and they were also more likely to have been charged with a violent offense than true confessors. They had higher responsibility scores than true confessors, and this sense of personal responsibility and tendency to make independent decisions may have given them an air of maturity and confidence that was not in keeping with their age. It is possible that this air of maturity and confidence, combined with their young actual age and general distrust toward legal authorities may have put them at odds with the police officers processing their charges. In keeping with this possibility, previous research suggests that the attitude of the adolescent when being processed is an important factor in how they are treated by police officers, as more of a victim or an offender (Halter, 2010).

In terms of the false confessors group, the profile of the false confessors was similar to true deniers in terms of psychosocial maturity and low perceptions of the fairness and legitimacy of legal authorities, but the fact that this group chose to falsely admit to a crime they did not commit suggests a different underlying motivation than the true denier respondent group. False admissions do occur (Kassin, 2014), even among adolescents (Arndorfer et al., 2015; Malloy et al., 2014) and can result from a desire to protect another person (Malloy et al., 2014) or due to a limited competence to engage in the legal system that can result in an admission of guilt that is more procured rather than offered voluntarily (Cleary, 2014; Kassin & Gudjonsson, 2004). Both of these examples are a possibility for our false admitter respondents. At the same time, their higher ability to control impulses and suppress aggressive responses, as indicated through higher temperance scores than the true confessors group, suggests that there was some thought put into their responses.

Implications

Our findings highlight the need to further review how psychosocial immaturity should be considered before youth speak with justice system personnel. The developmental needs of the adolescent, for example, through low psychosocial maturity, may confer an additional element of vulnerability in interactions with the justice system and additional legal supports may help the adolescent; for example in being ensured access to legal counsel or representation in legal interactions, especially considering that the United States Department of Justice found that more than 80–90% of youth forgo a right to legal counsel (Jones, 2004). Of course, waiver can happen at multiple stages of the juvenile justice system processing, from initial interview through probation revocation hearings, indicating a need to have access to counsel at all stages and steps in the juvenile process (National Juvenile Defender Center, 2018; Scali, 2019). At the same time, recent findings indicate that the presence of an interested adult during adolescent interrogations is associated with higher conviction rates of the adolescent, which suggests that the presence of the adult may serve to legitimize adolescents’ statements, regardless of the truthfulness of their statements (Mindthoff et al., 2020). Of notable interest, recent legislation has passed in the states of Illinois and Oregon in the United States that prohibit law enforcement from using deceptive tactics during interrogations of minors under the age of 18 (Innocence Project, 2021).

Internationally, the European Union (EU) Directive passed legislation in 2016 that provides children (under 18) with the right to an individual assessment prior to criminal proceedings, to determine whether any special assistance is required on the basis of “the child’s personality and maturity, the child’s economic, social and family background, including living environment, and any specific vulnerabilities of the child, such as learning disabilities and communication difficulties” (articles 35 and 36). In addition, the EU legislation recommends that all interactions between the child and police or law enforcement be audio-visually recorded to ensure sufficient protection for children who may not understand the content of the questions being asked of them (article 42). With these recent findings and legislation in mind, further efforts to find effective supports that provide a developmental buffer to assist in legal decision-making without disadvantaging adolescents are urgently needed in the United States.

Our findings also highlight the need to consider whether psychosocial immaturity may constitute a reason for not being competent to stand trial (e.g., Drizin and Leo, 2004; Mayzer et al., 2009; Scott and Grisso, 2005; Steinberg and Icenogle, 2019; Viljoen and Roesch, 2008). Overall, these findings provide information and context for legal authorities to be aware of when interacting with adolescents being charged with a first-time offense, most importantly that adolescents, in general, but especially those with low psychosocial maturity, may not have the developmental skills required for legal decision-making and are likely to require additional supports even from the point of initial contact.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to acknowledge in this study. First, we took the veracity of adolescents’ statements to the researcher at face value. However we did use several safeguards to increase the likelihood of adolescents telling the truth to the researcher. We had a Privacy Certificate from the Department of Justice that protected adolescents’ responses from ever being disclosed without adolescents’ consent, for example through a subpoena. We discussed the Privacy Certificate with adolescents before they began the study and also before the questions that were considered more sensitive. We also gave adolescents the choice to enter answers to sensitive questions into the keypad themselves by handing them the keypad device, or they were able to tell the interviewer what to input. Thus, adolescents should not have been motivated to lie to protect themselves in this situation. The fact that a great percentage of adolescents in this study did admit that they had committed the crime for which they were charged suggests that adolescents were generally comfortable sharing what happened.

A second limitation of the study is that the measures used relied on adolescents’ own reporting to gather information on their psychosocial maturity, offense, and perceptions of legal authorities. Future studies can consider examining reciprocal perceptions and interactions between adolescents and legal authorities, as well as reciprocal perceptions and interactions between adolescents and authority figures, including parents, more generally (i.e., lying to parents as a predictor of lying to authorities), to further inform professional practice involving the interactions between adolescents and legal authorities in the criminal justice system.

Conclusions

Overall, we found that adolescents were generally forthcoming to legal authorities about their involvement in committing a crime. Our results highlight the need to consider the psychosocial maturity of the adolescent in determining their ability and competence to interact with legal authorities about illegal activities. Of utmost importance, adolescents in general, but especially those with additional developmental needs, such as low psychosocial maturity, may need additional supports from the very first point of initial contact with legal authorities to assist with legal decision-making.