Abstract

Underlying various routes to peer influence on risky choices is the assumption that individuals have beliefs around their peer’s preferences which are incorporated in their choices. However, much is unknown about the accuracy of these beliefs and how they weigh in individuals’ considerations. We tested these implicit assumptions by actually collecting real-life peers’ preference to contrast with people’s prediction, and quantifying what changes when individuals were asked to take the peer’s perspective as the decision-maker instead of themselves. Since perspective taking develops through late adolescence, adolescence makes an especially dynamic window for observation. With a sample of typically developing friend dyads (N=128, 12.0-22.8 years), we collected fully mutual data on decision preferences in an economic risky decision making task with safe (certain) and risky (more variable outcomes) options that vary in their expected values. Upon establishing individuals’ baseline risk preferences and their prediction of their peers’ risk preferences, they took their own and their peers’ perspective in choices where their unchosen option was assigned to the peer. We modified an economic expected utility model to include a new parameter representing the adjudication between one’s own and friend’s outcome, and analyzed age-related changes with Generalized Additive Models. We found although peer’s risk preferences were overestimated in decisions on average, participants aged 16-22 years weighed friend outcome more and earned less when taking their friend’s perspective compared to their own, indicating this is a heightened period for prosocial considerations.

Peer influence has long been a factor of interest in risky decision making. Making a risky decision often has consequences not only for oneself, but also for the peers one surrounds oneself with. Consequences for peers impacts individuals’ risky choices (Powers et al., 2018) and a multitude of motives may drive an individual to modify their preferences when peers are involved, such as concerns of peer rejection and reputational considerations. However, before inferring the underlying motives that may give rise to peer influence, a more fundamental assumption is that the decision maker has beliefs about the desires of the peer and that these are indeed incorporated into their considerations. Research rarely explicitly measures the degree of (mis)calibration of these beliefs about peer preferences and how they are utilized in computations surrounding decision contexts where self- and friend-preferences might be at odds with each other (e.g., when an outcome is scarce and believed to be desired by both parties, and one must decide between keeping it or giving it to their peer). Understanding how beliefs about peer preference gets incorporated into the risky choice computation process can help shed light on the higherlevel question of motives behind why consequences for peers are influential.

An opportune window to study this question is the transitional period of adolescence. Developmental changes in several cognitive processes involved in peer-relevant risky decision making and the dynamic social landscape during adolescence make it a phase uniquely suited to study how beliefs about peer preferences are incorporated in these decisions. One cognitive mechanism required in weighing the pros and cons of prosocial decisions is perspective taking, which continues to develop through late adolescence (Dumontheil et al., 2010). Another is the incorporation of intentionality and social contexts in strategic fairness decisions (e.g., preferring fairness in order to maximize payoff, in case unfair offers get rejected), which increases with age in adolescence (Güroğlu et al., 2009). Making choices that maximize a peer’s outcome at the expense of one’s own requires cognitive control (Steinbeis et al., 2012), which also increases with age (Somerville & Casey, 2010). Thus, various processes that lay the foundation of the computations involved in these decisions develop well into adolescence, making it an opportune period to study risky decisions involving differing outcomes for self and peers, as information on age-related changes would contribute to a more thorough account of how beliefs about peer preference plays out in individuals’ decisions.

There are reasons to believe adolescence is a phase of life in which individuals may distinctively weigh peer outcomes heavily relative to their own when the two are in conflict. Specific age-related patterns in prosocial behaviors (voluntary acts intended to benefit others (Eisenberg et al., 2005)) have not been consistent in work to date. Some have argued this is due to discrepancies in the social contexts evoked by varying experimental paradigms, as prosocial behavior is increasingly sensitive to social contexts with age (Güroğlu et al., 2014). Despite this variability, consequences for peers are likely to encourage adolescents’ prosocial risk taking on several grounds. Peers become the dominant social group that adolescents spend most of their time with (Brown, 2004). Adolescents are also especially sensitive to peer rejection and value peer acceptance (Masten et al., 2011; Rodman et al., 2017; Silk et al., 2012). Thus, in addition to the developmental patterns of the aforementioned cognitive processes, the importance of peer relationships during adolescence also renders this age window particularly rich with age-dependent variances in individual’s beliefs about peer’s preferences in risky decisions.

The present study explored how implicit assumptions about peers’ preferences impact one’s risky choices in a sample that spans from early adolescence to early adulthood. We examine this lesser understood facet that is fundamental to peer influence by actually collecting data from peers about their own wishes and contrasting this with participants’ predictions of peers’ preferences. These predictions were used as input in a computational model, developed specifically for contexts that induce conflicting self- and friend- interest, permitting analyses on how one chooses differently from their own vs. their friend’s perspectives. Peer dyads in this study were age- and gender-matched friends in real life rather than strangers to evoke the possibility of genuine relational motives. Data collected were fully mutual (both individuals take on the role of the primary decision maker and of the peer being impacted) to test two specific questions about how implicit beliefs on peer preferences change across age:

1) The accuracy of people’s assumption about risk preferences of their peer.

2) With these beliefs as an input to the computation, whether participants would like their peer to prioritize themselves or the participant’s own wishes.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=128, age range: 11.98-22.82 years, N=37 adolescent pairs, ages 11.98-17.46 years; 18 pairs female and 19 pairs male; N=27 young adult pairs; ages 18.16-22.82 years, 14 pairs female, 13 pairs male; Male and female pairs were distributed evenly across the age range (logistic regression with age predicting gender, B=-0.014, p=.789) and pairs had an average age difference of 0.46 years (min=0.01, max=1.39, SD=0.33) were recruited in same-sex peer dyads who mutually identify one another as friends. Interested individuals identified a friend of approximately the same age and gender co-participate. Male and female pairs were distributed evenly across the age range (logistic regression with age predicting gender, B=-0.014, p=.789) and pairs had an average age difference of 0.46 years (min=0.01, max=1.39, SD=0.33). The distribution of average parental education level as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) was not related to age (linear regression, B=-0.016, p=.439), indicating SES is balanced across age. All were typically developing. Participants provided informed written consent/assent, and parents/caregivers of minors gave written permission for their participation. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Harvard University approved this research.

Risky Decision Making Task

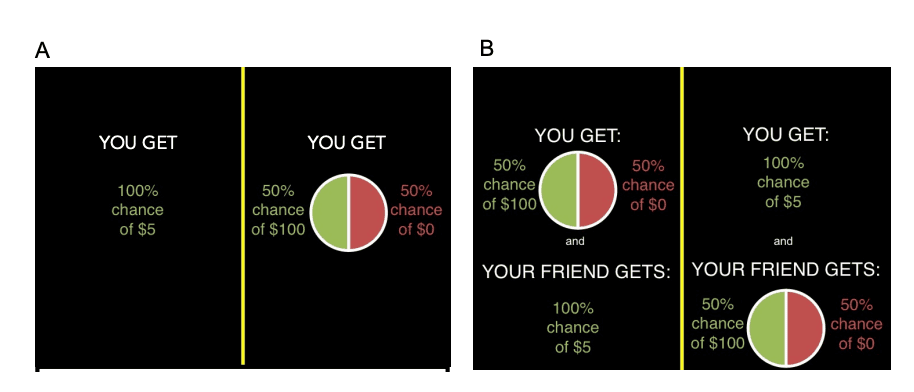

Participants completed an economic decision making task consisting of different choice options varying in monetary payout and odds of winning, which had been used in previous studies to quantify individuals’ risk preferences in adult (Chung et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2010; Sip et al., 2015; Tymula et al., 2012, Powers et al., 2018) and adolescent samples (Tymula et al., 2012, Powers et al., 2018). On each trial, participants selected between two choice options displayed on the left and right sides of the screen (Figure 1) varying in risk: a) a safe option “100% chance of winning $5” and b) a risky lottery option (10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, or 90% probability of winning [$5, $10, $20, $30, $40, $50, $100]; Tymula et al., 2012, Powers et al., 2018) depicted with a pie chart indicating the odds of winning and losing. Each probability was paired with each amount totaling 35 trials per condition, with the order of trials randomized. The safe and risky options were counterbalanced to appear on the left and right sides of the screen at equal frequency. Participants indicated their choice in self-paced timing by pressing one of two keyboard buttons, at which point the trial ended; there was no immediate feedback on the outcome of the decision. Participants were instructed that they and their friend would receive a fixed percentage of the cumulative amount of money they earned through their choices as a bonus in all conditions except for the Friend Predicted condition, with a computer simulating the chosen lotteries to determine earnings.

Experimental Procedure

Following screening and consenting, each participant completed an individual online testing session on Qualtrics in which they completed the following iterations of the risky decision making task in a pseudo-randomized order after comprehension checks of their understanding of the graphics: Baseline: Participants saw the graphics in Figure 1A while they answered the question: “What do YOU choose?”

Friend Predicted: Participants saw the same graphics as Baseline but instead answered the question: “What do you think your FRIEND will choose?” Since both members in a dyad took on the role of decision maker and friend, contrasting these two conditions permits analysis on the accuracy of predicted risk preferences for friends.

Opposite: Participants selected an outcome for themselves with the knowledge that the unselected option would apply to their friend (Figure 1B), answering the question: “What do YOU choose?” Essentially, they had to choose between keeping or giving their preferred option to their friend. Desired Opposite: Participants saw the same graphics as Opposite but instead were asked to imagine the screen from the friend’s perspective and answered the question: “What do you want your friend to choose?” They were told their friend would be able to see their choices from only this condition later.

Contrasting the Opposite and the Desired Opposite condition permits analysis on what aspects (see Dependent Measures) of the risky choices change when the decision maker took on the friend’s perspective. This differs from the Friend Predicted condition in that it is not asking participants to predict their friend’s actual choice but rather what they would do in their friend’s shoes.

Figure 1. Example graphics from different conditions in the experiment. A) from Baseline and Friend Predicted condition. B) from Opposite and Desired Opposite condition

Analysis Approach

Treatment of Age Because risk attitudes have been found to follow a nonlinear pattern from childhood to adulthood (Casey et al., 2011; Cauffman et al., 2010; Figner et al., 2009; Galvan et al., 2007), we adopted an exploratory data driven approach sensitive to nonlinear age related changes. Specifically, we fit a generalized additive model (GAM) (Hastie & Tibshirani, 1986, 1990) using the gam function from the mgcv package (v1.8.38, Wood, 2003, 2004, 2011, 2017) to examine the effect of age as a continuous predictor on the dependent measures.

To compare the age pattern for different levels of a categorical variable, GAM fits a nonlinear function for each level of a categorical variable (factor smooth interaction) without providing a direct statistical test for the interaction between the smoothed variable and the categorical predictor of interest. Therefore, we used the plot_diff function from the itsadug package (v 2.4, van Rij et al., 2022) to inspect the relative difference between fit estimates of each pair of conditions (i.e. Identical vs. Baseline, Opposite vs. Baseline) and compute 95% simultaneous CIs around it. Age bands where the simultaneous confidence interval (CI) did not contain zero are interpreted as periods of significant differences between the conditions.

Dependent Measures 1. Model-based estimation of risk attitudes: we fit a probabilistic choice model with two free parameters to each participant’s choices for Baseline and Friend Predicted conditions to quantify individual risk attitudes (Gilaie-Dotan et al., 2014; Levy & Glimcher, 2011; Levy et al., 2012; Levy et al., 2010). As in Powers et al. (2018), we modeled the expected utility of each option with a power utility function:

EU=pva

Where v is the amount of money on a given choice and p the probability associated with winning that dollar amount. a (Alpha) is the estimated parameter of interest for risk attitude, where risk is defined as outcome variability (Weber et al., 2004), i.e., the outcome with the greater uncertainty is the riskier outcome. Alpha < 1 indicates an agent is risk averse with a concave utility function, preferring the safe option to a risky option with equal expected value (EV; dollar amount multiplied by the probability of winning that option).

The Opposite and Desired Opposite condition required an adaptation of the model to incorporate the utility of the unchosen option assigned to the friend relative to that of the chosen option for oneself. This adjudication was reflected in the parameter w (Weightfriend):

EU=(1-w)PselfVselfa+w(pfriendvfriendafriend)

Where pself and vself are the probability and amount of money associated with the option participants intend to choose for themselves and pfriend and vfriend are associated with the unchosen option assigned to their friend.; afriend was estimated from the Friend Predicted condition with the original model, representing one’s assumed friend’s baseline risk preference. Weightfriend (w) represents how much one’s utility is based on one’s own outcome in contrast to how much one incorporates their estimation of their friend’s outcome and is bounded between 0 and 1. The larger it is, the more the participant values the utility of their friend’s outcome relative to their own. Alpha is still the free parameter to be estimated for participant’s risk attitude. Both Alpha and Weightfriend were analyzed as Dependent Variables as important aspects of risky choices in the Opposite vs. Desired Opposite contrast.

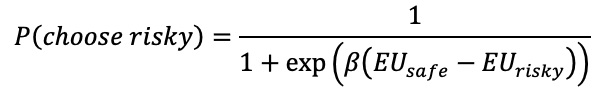

With both the original and revised model, we fit each trial within a condition to a logistic function that computes the probability of the participant choosing the risky option on that trial given the expected utility of the safe and the risky option, with a maximum likelihood procedure:

Where EUsafe is the expected utility of the safe option and EUrisky is the expected utility of the risky option. Beta is the inverse decision noise.

Parameter recovery showed that both models recovered robustly (r > 0.7). Model comparison showed that both outperformed alternative models for their respective conditions.

We also report results using Proportion of Risky Choices, calculated as the number of risky options chosen divided by total number of trials within a condition for each participant, as a more coarse-grained measure of risk preference to present trends in raw data for completeness. This measure is not as sensitive to changes in risk attitudes as Alpha, as the computational model takes into account the relative utility of the options on each trial, which Proportion of Risky Choices cannot capture. However, Proportion of Risky Choices is not subject to model-based exclusions (<10%) and thus presents a comprehensive sketch of the raw data.

2. Measure of simulated earnings: Simulated earnings were computed for each participant for each condition by calculating the sum of the expected value (EV) of each selected choice option. Simulated earnings were modeled as proportions of the total possible earnings (calculated as the sum of all highest-EV choices) using a beta distribution to better reflect the distribution of the data and improve the accuracy of the model fit and generalizability. Therefore, the test statistic is expressed in z-values and the resulting plots with y-axis on a logit scale.

Results

Accuracy of Friend Predicted Risk Seeking

This analysis evaluated the relationship between age and the discrepancy between how risk seeking participants predicted their friend to be and how risk seeking their friend actually was by comparing Alpha from the Baseline condition and the Friend Predicted condition. People on average estimated their friend to be more risk seeking than the friend’s actual risky choices indicated (Mean Alpha in Friend Predicted vs. Baseline: 0.63 vs. 0.55, B=0.08, t=2.45, SE=0.03, p=.015) but there were no age-related differences (95% simultaneous CIs included 0 at all ages). Evaluating this question with Proportion of Risky Choices, we did not observe this difference (Mean Proportion of Risky Choices in Friend Predicted vs. Baseline: .52 vs. .49, B=0.10, z=1.57, SE=0.06, p=.116).

Perspective taking: Desired Opposite vs. Opposite

To examine how the desired outcome for oneself changes when the decision was made from one’s friend’ vs. one’s own perspective, we compared the Desired Opposite condition (what do you want your friend to choose for themselves and you) and Opposite condition (what do you choose for you and your friend). We analyzed the changes in participants’ risky choices for themselves. Overall, participants chose the same option from their and their friend’s perspective with a .39 probability (95% CI [.38 - .41]). Below we report results on different aspects that characterized their risky choices: risk preference (Alpha), how much one values friend’s outcome relative to their own (Weightfriend), and to what extent they were maximizing their monetary payouts (simulated earnings).

Alpha There were no main effects of condition or age-related changes in Alpha (Mean Desired Opposite vs. Opposite: 0.75 vs. 0.69. B=0.06, t=1.28, SE=0.05, p=.203), indicating participants did not alter how risk seeking they are when thinking of themselves or their friends as the decision maker. Analysis using Proportion of Risky Choices instead of Alpha also did not show a difference between the two conditions (Mean Proportion of Risky Choices in Desired Opposite vs. Opposite: .54 vs. .56, B=-0.03, z=-0.37, SE=0.07, p=.709).

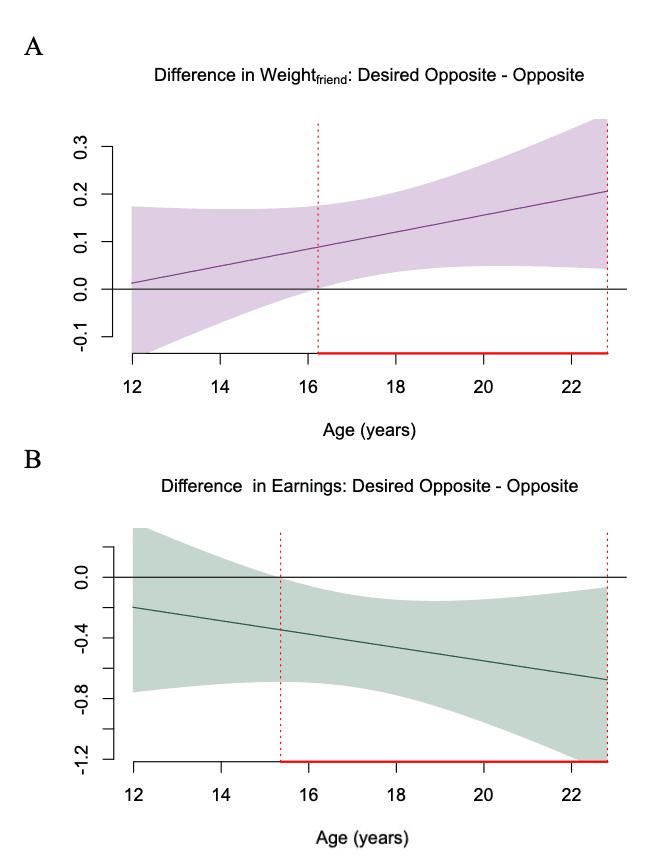

Weightfriend Evaluating the difference in how much friend outcome is weighed in one’s decision relative to their own based on our computational model, there was a main effect of condition (Mean Desired Opposite vs. Opposite: 0.46 vs. 0.35, B=0.11, t=3.21, SE=0.03, p=.002), indicating participants on average weighed friend-outcome more when they made decisions from their friend’s perspective than from their own. There was a significant age-related difference in this tendency between 16.2-22.8 years, and Weightfriend was not significantly different between the Desired Opposite and Opposite conditions for the rest of the age range. During this significant window from late adolescence to early adulthood, individuals weighed the utility of the option assigned to one’s friend more heavily when taking their friend’s perspective (thinking what decisions they would like their friends to make), compared to from their own perspective (Figure 2A).

Simulated Earnings Participants earned less overall in the Desired Opposite condition than in the Opposite condition (Mean Desired opposite vs. Opposite: 0.68 vs. 0. 80, B=-0.43, z=-3.56, SE=0.12, p<.001), when they took their friend’s perspective in assigning options to themselves. There was a significant age-related difference in this effect between age 15.4-22.8 years, indicating older adolescents and young adults assigned options to themselves that had lower expected values from taking friends’ perspective compared to their own (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Age-related patterns of risk seeking: difference of fit estimates of the GAM model. Shaded area represents 95% simultaneous CIs of the difference between fit estimates at each age point. A) Weightfriend: dotted red lines show that between 16.2-22.8 years, the 95% simultaneous CIs do not include 0, indicating a significant positive difference, suggesting people in this age window weighed friend outcome more in the Desired Opposite condition than in the Opposite condition. B) Proportion of simulated earnings: dotted red lines show that between 15.4-22.8 years, the 95% simultaneous CIs do not include 0, indicating a significant negative difference, suggesting individuals in this age window earned less in the Desired Opposite condition than in the Opposite condition.

Discussion

Through contrasting beliefs about friends’ preferences with their actual preferences, we aimed to assess the accuracy of these beliefs, which are often implicitly assumed or not given due consideration when considering routes to peer influence on risky decision making. Furthermore, we created a social context for risky decisions that entailed adjudicating on one’s own outcome and one’s friends, which necessitated a modified expected utility model to capture this aspect of the decision. Estimating one’s belief about an option’s utility for one’s friend incorporated individuals’ predicted risk preference for their friend as a necessary input; this then allowed us to observe the alteration in one’s own risky choices, including their risk preference (Alpha), how much they weigh their friend’s utility relative to their own, and the extent they maximize the expected payouts for themselves, when individuals reconsider the choices from their friend’s perspective. Furthermore, we selected a dynamic developmental period for perspective taking (Dumontheil et al., 2010) to tap into the potential motives behind changes in participants’ choices in a context where self-interest conflicted with friend-interest. Treating age as continuous permitted analyses sensitive to nonlinear changes that isolated the age windows of sensitivity in which individuals’ risk attitudes were modulated by whether they are making decisions as themselves or as their friend.

This study moves beyond past research in that it collected fully mutual data (both members of the dyad took on the decision maker and the friend role) and tested factors that are implicitly believed to matter in people’s decisions explicitly, as well as evaluated how these factors changed with respect to age. The modified expected utility model sheds light on the cognitive processes behind prosocial risky decision making. In particular, the model suggests in the social context that entailed keeping or giving away one’s preferred option, individuals’ social considerations occur in conjunction with monetary ones, and the balance shifts when individuals contemplate what they want their friend to choose compared to what they wanted in the first place.

The lack of age-related changes in predicted risk preference for friends is somewhat unexpected, as some theories suggested that contributing to adolescent’s heighten risk taking is the desire to assimilate to higher status peers (homophily, Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011); therefore, it follows that if adolescents are also especially prone to overestimating their peers’ risk preference, they might be motivated to take more risks themselves in order to gain social acceptance and avoid rejection, both are of special value during this period (Masten et al., 2011; Rodman et al., 2017; Silk et al., 2012).

Despite the finding that participants regardless of age slightly overestimated their friends’ risk preferences, the transitional period from mid-late adolescence to early adulthood seems to be a sensitive period for prosocial considerations, as shown in the age-related changes in simulated earnings and how much one weighed their friend’s utility relative to their own. Research has shown that self-outcome maximization and payoff comparison are increasingly incorporated in decisions that involve assigning consequences to self and others across adolescence, and that social context information takes an increasingly important role in shaping prosocial behavior (Güroğlu et al., 2014). The general pattern of age-related differences in the current study is in accord with this line of research.

Since our choice set makes it, on average, advantageous to pick the risky option for oneself, the fact that participants on average earned less but were not differentially risk seeking in the Desired Opposite condition compared to the Opposite condition could indicate that they were making more “irrational” choices, such that the risk seeking level stayed constant, but the risks were disadvantageous. This overall pattern holds in the significant age window as well – there were no age-related changes in Alpha at ages where participants’ earnings decreased.

Notably, the significant age window where the earnings decreased mostly dovetailed with when participants increasingly weighed their friend’s outcome, which makes intuitive sense – as friend-outcome was weighed more heavily relative to one’s own, individuals would sacrifice their own monetary gains. As participants knew the decisions in this condition would be seen by their friend later, we hesitate to attribute the motive behind this age-related increase in Weightfriend outcome to be purely selfless (i.e., wanting to maximize friends’ outcome at their own expense). Instead, reputational concerns could also be motivating this shift in behavior. It has been demonstrated that strategic prosocial behaviors (in which being prosocial is at least partly motivated by maximizing one’s own gains) increase with age during adolescence routing through development in perspective taking (Crone & Achterberg, 2022; Güroğlu et al., 2014; Overgaauw et al., 2012; Steinbeis et al., 2012). Maximizing one’s “gains,” as our computational model showed, could come from both monetary and social sources. Thus, it makes sense that as participants enter adulthood, in this decision context they would be motivated to demonstrate to their friend their considerateness. Fairness concerns could also be at play since we could conceptualize this result from the decision maker’s point of view as: “I want my friend to prioritize themselves and pick the better option (what I would pick for myself), but that does not necessarily mean I won’t prioritize myself when I am the decision maker. It’s only fair we both prioritize ourselves.” This could happen in parallel with reputational motivations as well, as being fair can be strategic here in gaining reputational benefits, and strategic fairness in decisions increases with age in adolescence (Güroğlu et al., 2009).

Taking a step back, the significant age-related changes observed could be driven by changes in both cognitive development and the social landscape. Flexible and sophisticated decision strategies increase with age with experience (Jacobs & Klaczynski, 2002); integrating across multiple sources of utility and simulating self- and friendoutcome requires late-developing brain areas responsible for complex cost-benefit analyses, such as the lateral prefrontal cortex (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Therefore, older adolescents and adults might be at a developmental stage more positioned for complex prosocial considerations. From a social environment perspective, self-reported loneliness peaks in late adolescence (Hamond, 2019) and some suggest that shifts in social expectations, identities, and relationships, which necessarily occur during this transition in particular, contribute to the experience of loneliness (Tomova et al., 2021). Avoiding social risks of being excluded is a pillar that drives adolescents’ tendency to behave in ways that peers endorse (Blakemore, 2018; Blakemore & Mills, 2014; Tomova et al., 2021), and this motive could be especially salient at this dynamic period. As Tomova et al. (2021) pointed out, accommodating behaviors sometimes entails taking more risks and sometimes entails not doing so, which could explain why there was no significant age effects on risk seeking, while the age effects on earnings and weight individuals assign to friends’ outcome was present.