Abstract

Financial well-being is becoming more prominent in policy, research, and the financial sector. However, there is a lack of understanding of its meaning, and the vast majority of financial well-being research employs quantitative methods whereas recent literature reviews advocate for qualitative studies into the meaning of financial well-being and its associations with age. We contribute to that by conducting exploratory qualitative research into the phenomenon of perceived financial well-being and its components. It is based on three studies each of which used in-depth semi-structured interviews (N = 47). The first key finding is that youth perceive financial well-being to be comprised of three components: keeping the current lifestyle and making ends meet; achieving desired lifestyle; and achieving financial freedom. In contrast, older groups distinguish only two: keeping and achieving the lifestyle in the present and in the future. The second finding is that the definition of financial freedom differs across age groups. Young people aspire to become financially independent, while middle-aged individuals prioritize supporting their children, and older people are afraid of becoming a financial burden. Third, regardless of age, many do not plan, save or invest for securing their financial well-being. We conclude by proposing implications for increasing financial well-being in different age groups, and suggesting paths for further investigation.

Introduction

Over the last decade, financial well-being (financial health, financial resilience) has been gaining increasing attention (Kaur et al., 2021; Wilmarth, 2021). On the one hand, policy-makers have paid special attention to it since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021). On the other hand, financial institutions have a changing role due to digitalisation and open banking, which disrupts the role of traditional banks; as a result, many of them have explicitly stated financial well-being or financial health to be their target of interest (Comerton-Forde et al., 2020; Money and Pensions Service, 2019). From a third perspective, because financial well-being is seen as the ultimate outcome of financial education (CFPB, 2015), providers of financial education are starting to focus on it more, rather than simply teaching basic financial facts and skills. However, there is a lack of understanding about what financial well-being entails for individuals and how it should be measured.The majority of research and policy reports use quantitative methods for assessing financial well-being (FWB). Only a few authors have gone further, studying the meaning of financial well-being for individuals using qualitative methods (Rea et al., 2019; Salignac et al., 2020). However, little is known about how the meaning of financial well-being changes with age. There is some indication that the components of financial well-being can differ with age (Wilmarth, 2021), and that some young adults see it as a continuum while others perceive it to be absolute (Rea et al., 2019). There are quantitative studies that show how the evaluation of financial well-being differs across age groups (Riitsalu & van Raaij, 2022), but these do not take into account how the meaning, and therefore conceptualisation and operationalisation, of FWB might change over the course of one’s life. As highlighted by Wilmarth (2021, p. 126):

There is still a gap in the literature in using comprehensive financial and economic well-being measures with age specific components, and if the antecedents change with age. Moving into the next decade, continuing to have age specific investigations on financial and economic well-being measures would help to expand the body of knowledge for both researchers and practitioners.

Recent literature reviews have emphasised a lack of qualitative studies of financial well-being. Kaur et al. (2021, p. 235) call for “studies using qualitative approaches such as interviews to gain new perspectives on FWB.” Wilmarth (2021, p. 129) suggests that “researchers could take advantage of qualitative methods to understand more about the personal aspects and experiences of financial and economic well-being.” Our goal is to fill this void by investigating the meaning of financial well-being in three qualitative studies, with a total sample size of 47 individuals. In the first study, we interviewed young people aged 17 to 23. In the second, we interviewed middle-aged individuals, and in the third, we interviewed those nearing retirement age. All three studies were carried out in 2021 in Estonia during the COVID-19 pandemic (the first two in spring, the last in summer).In the following section, we summarise recent literature on financial well-being, discuss its conceptualisations and antecedents, and analyse previous findings related to the possible differences in the perception of FWB across age groups. In the third section, we introduce the research questions and explain the choice of methods. In the fourth section, we present the results of the three studies, followed by a discussion of the findings and their theoretical contribution. The paper concludes with practical implications and suggestions for further research.

Theoretical Background

There has been a substantial increase in the number of financial well-being studies in the last few years, and several literature reviews (Gonçalves et al., 2021; Kaur et al., 2021; Nanda & Banerjee, 2021; Wilmarth, 2021) and special editions of FWB (Kabadayi & O’Connor, 2019) have been published. For example, Kaur et al. (2021) analyse publication trends for 1995–2019, Gonçalves et al. (2021) for 1991–2020, and Nanda and Banerjee (2021) for 1978–2020. All of these reviews indicate a significant increase in financial well-being research, which has accelerated in recent years. Furthermore, there has been an explosion of FWB publications in grey literature, with many policymakers and financial sector institutions recently publishing FWB (or financial health) reports (see for example Comerton-Forde et al., 2020; UNCDF, 2021; UNSGSA, 2021). However, financial well-being research “is still at its nascent stage” (Kaur et al., 2021, p. 235).

Approaches and Definitions

Subjective well-being is defined as the combination of feeling good and functioning well (Ruggeri et al., 2020). As FWB has been found to have the biggest role in subjective well-being (Netemeyer et al., 2018), one might wish to expand upon the same definition. Financial well-being could be interpreted as feeling good about one’s personal financial situation and being able to afford a desirable lifestyle now and in the future. Nevertheless, there is no one agreed upon definition; instead, there are several approaches and conceptualisations that we summarise.There are several terms used, sometimes interchangeably with FWB: financial wellness, financial health, financial satisfaction, financial comfort, financial resilience (Nibud, 2018; Schmidtke et al., 2020; Sorgente & Lanz, 2017; Xiao & Porto, 2017). A recent policy document (UNSGSA, 2021) explicitly states FWB to be a synonym for financial health: “Financial health – or wellbeing – is an emerging concept that addresses the financial side of individuals’ and families’ ability to thrive in society.” We will not review all concepts in the present study, as several reviews have been recently published (e.g., Kaur et al., 2021; Warmath, 2021).Financial well-being has been defined by Brüggen et al. (2017) as “the perception of being able to sustain current and anticipated desired living standards and financial freedom.” The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB, 2015) defines it as “a state of being wherein a person can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices that allow enjoyment of life.” The rare qualitative studies provide richer insights into the meaning in various groups. In a study of financial socialisation of young adults conducted in the United States, Rea et al. (2019, p. 261) found that those they studied interpret FWB as “as an ability to balance taking care of their money for stability and freedom to live independently from their parents, with feeling unconstrained by their finances.” Salignac et al. (2020, p. 1596) explain it based on their qualitative study conducted in Australia: “a person is able to meet expenses and has some money left over, is in control of their finances and feels financially secure, now and in the future”.There are several approaches to conceptualising and operationalising FWB. Brüggen et al. (2017) composed a financial well-being framework comprising of contextual factors, financial well-being interventions, financial behaviours, the consequences of financial well-being, and personal factors. Kempson and Poppe (2018) developed a conceptual framework based on a pilot study in Norway in 2017, refining it in consecutive studies in Ireland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Kempson, 2018). Their model includes financial knowledge and skills, behaviours, attitudes, socio-economic status (income, household size), and personality characteristics. Barrafrem et al. (2020a) emphasise the role of contextual factors. Gonçalves et al. (2021) highlight the effects of household-, community-, and societal-level factors on FWB.Some find FWB to be one construct and measure (Barrafrem et al., 2020b; Strömbäck et al., 2020), while others divide it into two or more components, mostly distinguishing its present and future elements. In their qualitative study, Salignac et al. (2020, p. 1596) found that FWB has three dimensions: meeting expenses and having some money left over, being in control, and feeling financially secure. Netemeyer et al. (2018) divided FWB into two components: current money management stress (CMMS) and expected future financial security (EFFS). They found that the drivers of the first component are late payments, materialism, and lack of self-control, and of the second component are perceived financial self-efficacy, positive financial behaviours, willingness to take investment risks, and long-term planning. Both of these components influence overall well-being, but when included in their analysis simultaneously, the effect of CMMS on well-being is mediated by income. However, it is important to highlight they show FWB to have the largest influence on overall well-being. Ponchio et al. (2019) employed the CMMS and EFFS scales in Brazil. They found consumer spending self-control, materialism, and time perspective to predict both components of overall financial well-being, and personal saving orientation to affect expected future financial security. Riitsalu and van Raaij (2022) used the same measures in data from 16 countries and found income to be a significant predictor of both components of FWB. They also suggest that financial well-being may differ more across age groups than countries due to consumer culture and globalisation.There are different approaches to measuring FWB, some prefer objective measures, such as saving and debt ratios (Greninger et al., 1996), while some use subjective measures, such as ratings on Likert scales of one´s financial anxiety, worry, or stress (de Bruijn & Antonides, 2020; Netemeyer et al., 2018; Strömbäck et al., 2020), with others suggest to combine both (OECD, 2020a; Porter & Garman, 1993). It appears that the subjective approach is gaining more support, as it reflects the perceptions and values of individuals better than objective indicators allow to understand (Riitsalu & van Raaij, 2022), but, however, controlling for objective measures may give stronger ground for designing interventions for increasing FWB.

Factors that have an Effect on the Perception of FWB

At first glance, one might assume that having sufficient income and stable economic and political environment might be enough for securing financial well-being. Analysis of recent findings shows it to be far more complex. First, reference groups matter, as emphasised by Porter and Garman (1993). The pressure to keep up with the Joneses may mean that even high incomes are insufficient for reaching a desirable standard of living. If the norm is to have the newest smartphone or the largest house, then reaching the desired living standard can seem more complicated than for those with less materialistic values (Garðarsdóttir & Dittmar, 2012). When one’s neighbour drives a flashy new car, one’s current financial situation may seem less favourable than it would be without this pressure to maintain appearances.Second, income inequality may make the size of assets seem unfairly small, even if it is suitable for the maintenance of the current standard of living. In data from five countries, a negative correlation was observed between the Gini coefficient, an indicator of income inequality, and financial well-being (Kempson, 2018). Therefore, if the financial circumstances vary greatly within a country, individuals perceive themselves as having lower financial well-being.Third, the assessment of FWB can be heavily influenced by the timing in which the questions are being asked from the individual. For example, current money management stress can be perceived to be higher a few days before payday when there is only a small amount left in one’s current account, on the due date for payment of monthly utility bills, or after applying for a mortgage that will shake up the budget. On the other hand, money management stress can be perceived to be lower right after payday. As there is evidence that people spend much more on discretionary immediately after payday, regardless of their level of income (Olafsson & Pagel, 2018) than the rest of the month, then during these few days they may be less stressed about making ends meet. Similarly, right after receiving the tax refund or some other lump sum that feels like a windfall, they may be overly optimistic about their financial well-being. Life events also have an effect on the evaluation of financial well-being (Brüggen et al., 2017; Salignac et al., 2020).Perceptions of financial well-being can be influenced by the news, opinions, and macroeconomic circumstances. It is possible that a populist party decides to declare the retirement system completely flawed and promise to give people all of the money saved in mandatory pension funds as a lump sum after they win the election (the case of EstoniaFootnote1) and invest large sums of money and efforts into declaring through all possible channels that financial futures are doomed (unless they win the elections). This can lead to many people believing that their expected future financial security is bleak. Similarly, when the news warns of looming economic crises or even war, the perception of expected future financial security can worsen. On the other hand, news about economic growth and positive future outlooks can make one overestimate their financial future.

Age, Financial Literacy, Subjective Financial Knowledge and FWB

There is contradictory evidence of the relation between age and FWB. Some found it to be U-shaped: higher FWB among youth and older age groups, lower in middle age (Riitsalu & Murakas, 2019; Xiao & Porto, 2017). Some observed it to increase with age (de Bruijn & Antonides, 2020; Fu, 2020), while some noted it to be lower in older age groups (García-Mata et al., 2022), and others found no significant correlation between age and FWB (Strömbäck et al., 2020). One of the few qualitative FWB studies found evidence that the meaning and components (or dimensions) of FWB change over the life-course (Salignac et al., 2020). That study was conducted in Australia, and we investigate if similar changes occur in Europe.Previous research has mixed results on the relation between financial literacy and financial well-being. Richards et al. (2019, p. 17) found that financial knowledge has “an indirect relationship with financial wellbeing rather than a direct one.” Ponchio et al. (2019) showed financial knowledge to influence current money management stress but to have no correlation with expected financial security. Kempson et al. (2018) uncovered that personality characteristics, such as financial locus of control and confidence, overrode the effects of financial knowledge. Lee et al. (2020) found in data from the United States that the propensity to plan personal finances moderated the relation between financial knowledge and FWB. Utkarsh et al. (2020) studied the correlation between financial literacy and financial well-being in India and found it to be nonsignificant. Instead, they showed attitudes and financial socialisation to have an effect of FWB of young adults.Riitsalu and Murakas (2019) showed in data from Estonia that subjective financial knowledge and prudent financial behaviour were better predictors of financial well-being than objective knowledge. Subjective financial knowledge is the confidence in the sufficiency of personal financial knowledge. Similar positive effects of financial confidence, rather than objective knowledge, on financial well-being were shown by Kempson et al. (2018) and Lind et al. (2020). These findings suggest that financial knowledge and skills do not always lead to action for securing the financial future. Nanda and Banerjee (2021, p. 761) concluded in their literature review, “much is left to be learned in financial literacy and the FWB relationship.”The relation between financial behaviour and financial well-being can be bi-directional (Schmidtke et al., 2020). On the one hand, deliberate choices and prudent behaviour correlate positively with financial well-being (Hoffmann & Risse, 2020; Riitsalu & Murakas, 2019). Those who save actively have higher financial well-being (Anvari-Clark & Ansong, 2022; Kempson & Poppe, 2018) while those taking on too much debt have lower financial well-being (Garðarsdóttir & Dittmar, 2012; Richards et al., 2019). Those who have higher financial self-efficacy engage more in prudent financial behaviours and therefore have higher FWB (Dare et al., 2022).On the other hand, this relation can also run in the opposite direction. The perceived inability to maintain one’s living standards – an inability to keep up with the Joneses – can tempt one to apply for consumer loans. This assumption was supported by the OECD’s squeezed middle class analysis (OECD, 2019), which showed that four in ten middle-income households were in a financially vulnerable state; in the event of a loss of income or any other negative event, they would have immediate trouble coping with their costs and obligations. Therefore, aspirations for a lifestyle that is beyond an otherwise adequate income level or the perception of low financial well-being, can lead to unreasonable choices. Furthermore, it has been found that financial capability increases financial stress for those who can be classified as debt delinquents (Xiao & Kim, 2022). However, pooling financial behaviours as one construct or indicator can be misleading (Willis, 2021). It has been shown that short-term financial behaviour can have a positive effect while long term financial behaviours can have a negative effect on FWB (Fan & Henager, 2022).There is indication that the relation between financial competence and FWB can differ across age. In a recent study of vulnerable groups in the United States, Xiao and Porto (2021) found that financial skills had a significant effect on FWB for older individuals while financial behaviour was a better predictor of FWB for the younger and middle-aged individuals.

Country Context

Our studies were conducted in Estonia. As indicated above, country context has an effect on FWB, and therefore we provide a brief overview of the country’s background before introducing methods and results.Estonia is a small country in Northern Europe, with population of 1.3 million people, and a member of the European Union. Despite its post-Soviet background, the country takes pride in its digital and educational development. In the most recent PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) financial literacy survey, Estonian students ranked first among the participating countries around the world with highest mean financial literacy score (OECD, 2020b). In adult financial literacy surveys, Estonians have high financial knowledge but mediocre behaviour scores (OECD, 2016, 2020a; Riitsalu et al., 2018). The national strategy for financial education was launched in 2013, and the next strategy document is being implemented for years 2021–2030 (Põder et al., 2020).In September 2021, the average monthly gross wage in Estonia was 1,563 euros (Estonian Bank, 2022). According to the OECD data, household debt in Estonia was among the lower ones in the EU (77% of disposable income, 2019 data) and savings above the average (9.6% of disposable income, data from 2019) (OECD, 2022b). Income inequality was slightly higher than the EU average (Gini coefficient 0.305, where 0 = complete equality and 1 = complete inequality, data from 2019), and poverty rate among 66 year-old or older individuals was incredibly high – 0.376, data from 2020 (OECD, 2022c). Gross domestic product (GDP) for Estonia in 2020 was 37,984 USD per capita (OECD, 2022a).

Method

Our aim was to investigate the meaning of financial well-being for individuals and how these perceptions and conceptualisations differ across age groups. In order to do so, we posed the following research questions:

1.

How do individuals perceive their financial well-being? Which components do they see it including?

2.

Does the meaning of financial well-being differ across age groups? If so, how so?

3.

Which factors do individuals believe are the antecedents of financial well-being?

4.

Do the individuals plan, save, and invest for increasing their financial well-being?

5.

Do the individuals perceive a correlation between their financial knowledge and FWB?

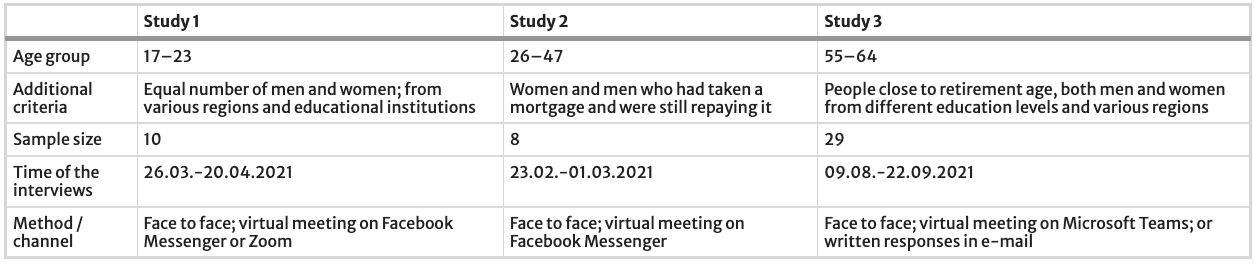

For finding answers to these questions, we conducted exploratory qualitative research into the phenomenon of perceived financial well-being and its components. It is based on three studies, each of which used in-depth semi-structured interviews for collecting the data in order to gain a deeper understanding of the views and experiences of participants (Kvale, 2006). In each of them, selective sampling was used, and the criteria for inviting into the studies can be seen in Table 1. The eligible participants were informed about the purpose of the study and invited to meet if they gave their informed consent to participate.

Table 1 Sample of the three qualitative studies

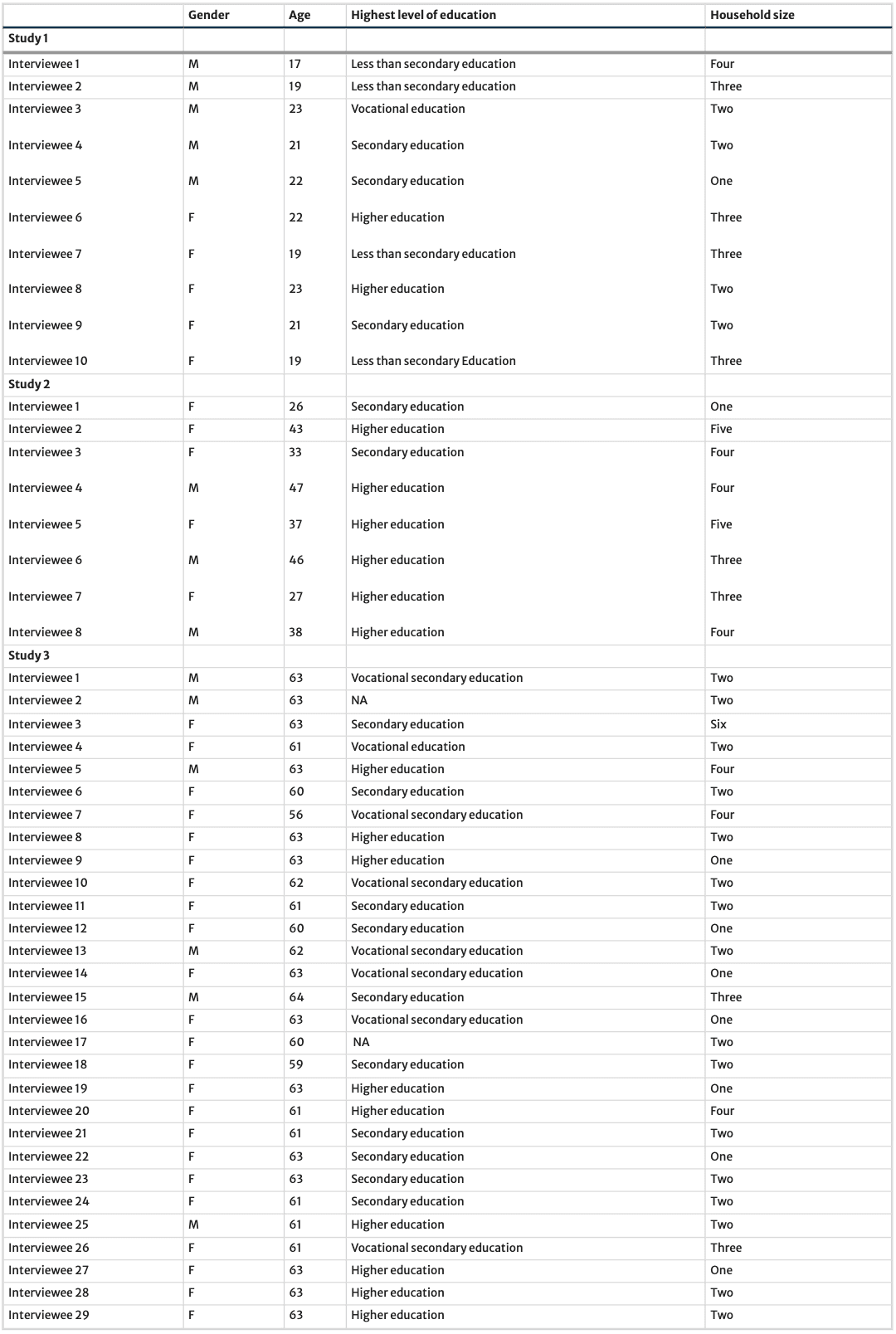

Because the data was gathered during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the interviews were conducted remotely, without being physically in the same room. Data collection lasted for approximately a month for each session, and the exact dates of data collection are provided in Table 1. The details of the interviewees (age, gender, and household size) can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2 Codes and details on interviewees

The interviews were fully recorded and transcribed in Estonian, and the participants were given codes to protect their identities.In the first two studies, content analysis was used. First, the interview transcripts were coded using open coding to allow for new meanings to emerge. Next, categories and higher categories were developed from these codes. Finally, the data were analysed for finding patterns and conclusions.In the third study, thematic analysis was used. The aim was to “report experiences, meanings and the reality of participants” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 81) and identify common themes across the set of data (DeSantis & Ugarriza, 2000). As a result, an iterative process of data coding, theme development, and revision was initiated.At this stage, we worked inductively, guided by the content of the data. We followed the six phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006): (1) familiarise yourself with your data; (2) generate initial codes; (3) search for themes; (4) review themes; (5) define and name themes; and (6) produce the report. First, all vignettes were read several times. Then, segments that were identified as relevant to our research question were marked and comments were added to these. The initial coding process was carried out by one of the authors, aiming to recognise items that may form the basis of themes, while being cautious about interpretations. After the iterative initial coding, the codes were discussed with other authors. Rather than for specific keywords, we looked for meanings. Then, all codes and data extracts were combined for the next stage of analysis. The phase of identifying potential themes was again carried out initially by one of the authors, who examined the codes, arranged and rearranged them in order to develop initial themes. We saw themes as entities that captured the substance of meaning that recurs in our data set (Braun & Clarke, 2016).

Results

Study 1 – Meaning of Financial Well-being Among Youth

Young people explained financial well-being mainly from the perspective of lifestyle, often as the ability to be able to afford everything one desires. However, several respondents made it explicit that this did not mean extensive wealth, it was more about enjoying life. For example, one respondent explained:

Financial well-being starts for me from my perspective on the world, and only then does money come into play as a means for living a life that is pleasant for oneself, that offers enjoyment. /…/ Financial well-being does not mean that I should be able to afford myself everything I desire. (Interviewee 4)

Another component that emerged from the interviews was the ability to keep the current lifestyle, to be able to make ends meet, and to cover all costs and fill all obligations. In this context, also feeling secure was mentioned by interviewees, either through having a sufficient savings buffer or passive income from one´s investments. They saw it as a way to protect oneself from a “rainy day” or to be able to cover unexpected costs.Several young respondents mentioned plans to earn passive income in the future without having to work full time:

Financial well-being is when you do not have to work and you earn passive income, /.../. (Interviewee 1)

Again, they did not see it as extreme wealth but as earning enough from investments to cover daily costs. However, most of them had not yet taken substantial steps to invest for achieving financial freedom in the future. It was perceived as something that would happen in the future, even rather easily.Some of them explicitly stated that viewing financial well-being as wealth is incorrect, for example:

In my opinion, financial well-being is that you have a home where you live, and you are satisfied with it, you have a car that you drive and get all your stuff done. And you have some money set aside, so when you wish to buy something, you can afford it. I do not mean some large amounts, in fact not much is needed for being satisfied with what you have. (Interviewee 5).

Respondents made it clear that they did not wish to have to earn money in the same fashion as previous generations, for example:

Modern youth does not want to be employed and live from payday to payday like our parents and many others do. (Interviewee 3)

They preferred to be entrepreneurs, engage in activities they found fulfilling, or achieved financial freedom through investing. As one of them aptly stated:

/…/ to enjoy life without chasing money. (Interviewee 4)

In summary, the main categories that emerged from the interviews with young people were:

1.

Keeping the current lifestyle and making ends meet;

2.

Achieving a desired lifestyle;

3.

Achieving financial freedom.

The following definition of financial well-being for youth can be formulated:

Financial well-being means keeping the current lifestyle and reaching a desired lifestyle in the future, and it includes being able to cover necessary expenses and obligations, ideally being able to afford in the future anything one desires. That kind of life is enabled by financial freedom with passive income or stable and good income that allows regular savings.

Being able to participate in economic life, supporting local small enterprises, consuming ecological products and reducing one’s ecological footprint, and participating in cultural activities were mentioned as outcomes of satisfactory financial well-being.Interestingly, when asked about who should take the responsibility for increasing financial well-being, many respondents paused and struggled to find an answer. It appeared that many of them had never thought about it previously. It was noted that one should take responsibility for their own financial affairs, but also schools, policymakers, employees, and parents were mentioned.When asked about financial planning, saving, and investing, it became rather clear they did not (yet) engage in prudent financial decisions. Half of the respondents had saved some money or invested within the last 12 months. Those who had invested, mentioned crypto assets, peer-to-peer lending platforms, and stocks.

Study 2 – The Meaning of Financial Well-being Among Middle-aged Individuals

Middle-aged individuals perceived financial well-being as the ability to make ends meet and not having to worry about finances.

Basically, I feel I experience financial well-being when I meet every day needs when I go grocery shopping and do not need to look at the costs. (Interviewee 8)

I experience financial well-being in such a way that I don’t have to worry about money. (Interviewee 3)

There were respondents for whom FWB meant financial security, while for others it referred to freedom of choice in decision-making. Some of the respondents showed these two – financial security and freedom of choice – to be two separate components of financial well-being. Once the first was secured, the second could be achieved:

Freedom of choice. I already have financial security and opportunities. Now, I want freedom. I want to work less, but travel and be the master of my time. (Interviewee 3)

Financial freedom was not explicitly mentioned in this group, as it was in Study 1, but it was implied in the context of having to work less as above and being less dependent on work:

You have to invest so that you don’t have to work one day anymore. You should only work because you like it, not because you have to. (Interviewee 7)

It was also mentioned that where there was freedom, there was also a sense of security. According to the interviewer, the responses did not depend so much on age or income, but rather on the respondents’ general economic situation.Similarly to the younger group of interviewees, financial well-being was ultimately seen as the ability to enjoy life.

The inner satisfaction when you are happy and everything is fine. That there is no nagging feeling that something is not right (financially). (Interviewee 4)

It was also stated here that financial well-being did not imply wealth:

Financial well-being is guaranteed when basic needs are met and a little more. (Interviewee 6)

It was mentioned that as one’s income increased, so did one’s spending, but there might be less time left to enjoy life. As a result, when more money meant more work, there was no happiness and life satisfaction left, and thus no FWB.Subjective financial knowledge, peer effects, uncertainty due to the pandemic, and trust in government were the factors that were mentioned as the antecedents of FWB. When asked about their financial behaviour, a few participants revealed their long-term goals vaguely but did not link them to any specific saving or investing activities. Their responses did not indicate that the participants’ perception and interpretation of FWB would include any specific saving or investing strategies.For this middle-aged group, FWB meant that their needs were met, they had the freedom to buy whatever they wanted, and they had financial security. As a result, they described the present and future components of financial well-being without aspiring for financial freedom described by the youth.

Study 3 – The Meaning of Financial Well-being Among Individuals Nearing Retirement Age

Individuals close to retirement age defined financial well-being mainly as financial independence from others, a situation where all their needs were met:

Financial well-being is when there is enough money for all my needs, absolutely for all my needs. Let’s say […] that there is enough money for travelling, for living and buying things. In my opinion, this is financial well-being. (Interviewee 8)

According to several interviewees, financial well-being also meant that they were able to financially support their close family members, such as their children. In comparison with other studies, this factor seemed to be more relevant in this age group, as many interviewees nearing retirement age had families. One respondent described how he associated financial well-being with for example, helping his children in purchasing a new home.A couple of interviewees in this age group mentioned having “funeral money,” a component of financial well-being not found in other studies:

I live pay check to pay check, I don’t have any savings, not even for a funeral. (Interviewee 16)

While several individuals saw financial well-being as having enough money, a couple of interviewees distinguished it clearly from wealth:

Well, let’s say that money has not made me happy in that sense, and it could also lead to problems. Rather, I am satisfied that I can financially support my everyday activities. (Interviewee 13)

For me, money is not important; money is only an instrument. (Interviewee 1)

However, the two important antecedents of FWB were identified as health and employment options. Without one or both of these, it was impossible to earn sufficient income that was needed for securing FWB.Over half of interviewees stated that they had saved some money for their upcoming retirement. For some interviewees, this had not been a conscious planning decision, but rather that they had some extra money that they decided to save.While many respondents had savings, only a couple had invested in stocks, funds, or real estate to ensure their financial well-being. Several individuals indicated that the main reasons for not investing were a lack of knowledge about the subject and unwillingness to risk with their own money:

Unfortunately, I do not have any investments. It would be interesting, but I am really careful as well as ignorant in these things, which is why I think that I am not going to invest. But one will never know. (Interviewee 20)

Most of the interviewees said they had no regrets about the decisions that they had made regarding their financial well-being. However, one respondent described a situation in which she had invested in an unsuccessful pyramid scheme in the 1990s:

At the beginning of the 1990s, I joined a pyramid scheme that at first spilled money, but afterwards, the bubble burst and everyone lost their money. The amount that I lost was quite small, but it was still a lesson for me. (Interviewee 4)

In conclusion, individuals nearing retirement age associated financial well-being with present and future financial independence. Compared to the first two other studies, two distinct aims of securing financial well-being emerged in this group: having “funeral money” or savings for later in life and having money to support their families.

General Discussion

Theoretical Contributions

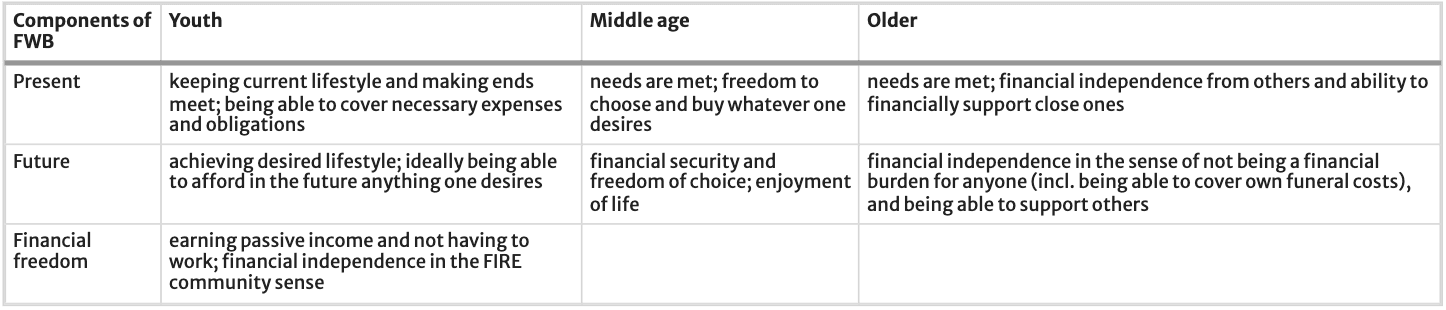

Our first research question was, how do individuals perceive financial well-being, and what components do they believe it consists of. The common thread that emerged from the interviews in all studies was the perceived ability to keep the current life-style, the first component of the Brüggen et al. (2017) conceptualisation. This entails making ends meet without stress and feeling secure about one´s personal or household´s finances – the first component of several other conceptualisations (CFPB, 2015; Kempson & Poppe, 2018; Losada-Otálora & Alkire (née Nasr), 2019; Netemeyer et al., 2018). In all studies, some respondents explicitly stated that FWB does not imply wealth and is more than just having enough money.Differences in the perception of the future element(s) of FWB emerged. From the responses of the younger individuals in the first study, two more components of FWB emerged: achieving desired lifestyle in the future and reaching financial freedom. These were surprisingly clearly explained as the two last components of Brüggen et al. (2017) conceptualisation. Financial freedom means something different to young people as it does for older individuals. Youth interpreted financial freedom as earning sufficient passive income and not having to work in the traditional way that previous generations saw as the default option. This is similar to the principles of the FIRE (Financial Independence Retire Early) movement (Taylor & Davies, 2021). Some of them explicitly stated the ecological arguments that the FIRE philosophy prioritizes. The latter prioritizes frugality, reduced consumption, and extreme saving in order to earn passive income and enjoy free time.Among the middle-aged and older respondents in the second and third study, only one forward-looking component of FWB was described: financial freedom or independence, interpreted as a freedom of choice, following the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB, 2015) approach. They saw it as having the freedom to choose how to earn and spend money without being forced into certain choices by their financial situation. It meant striking a better balance between work and leisure time. In the older group, financial independence was prioritised, which was understood as not needing financial support from anyone until the end of the life, including being able to cover one’s own funeral costs. As a result, the answer to our second research question is affirmative, as the meaning of financial well-being varies across age groups, as does the interpretation of its components (see Table 3).

Table 3 Components of financial well-being and their meaning for the three age groups

Our findings indicate that younger people saw FWB as a three-stage journey, while older ones perceived it as a two-component concept. It might be related to their life stage – youth were only starting to manage and plan their own finances, build their careers, and find their desired lifestyle, while middle-aged and older individuals have already come to the mid-point of this journey and established their standard of living. It is also possible that they are simply more realistic about their opportunities than the youth.We investigated how the perception of FWB has changed over time, and the middle-aged group indicated that their values had become less materialistic. Previously, it may have been more about building the social status, but now it is more about enjoying life. On the one hand, this may reflect the change of social norms in a post-Soviet country, from highly individualistic and materialistic to more post-materialistic values (Harrison et al., 2016). On the other hand, it may simply be they reached an acceptable socio-economic status. It could also be because the FIRE philosophy is popular only among the young (Taylor & Davies, 2021).Our third research question inquired about the perceived antecedents of FWB. In all three age groups, family and household members are said to have an effect on financial affairs. This supports previous research on the effects of family and financial socialisation on FWB (Rea et al., 2019; Wilmarth, 2021). Among young people, parents are still a source of income and support; in middle age, respondents support their children and partners; and older individuals fear becoming a financial burden while hoping to be able to support children and grandchildren instead. In all age groups, peer effects matter as well. Whether explicitly or implicitly, people do compare their financial situation and lifestyle to others of a similar background and estimate their FWB accordingly. In addition, the older interviewees underscored the importance of health and employment for securing and increasing FWB.Planning, saving, and investing are essential for securing and increasing FWB. Although none of the respondents disputed that correlation, most respondents in all three studies did not have financial goals or plan, nor do they save or invest on a regular basis. Hence, the answer to the fourth research question is negative, as many individuals do not plan, save, and invest explicitly and knowingly for the purpose of increasing their FWB. This refers to Financial Homo Ignorans, which is the proclivity to ignore complicated financial decisions (Barrafrem et al., 2020a), instead taking the path of least resistance rather than making investment choices (Choi et al., 2002; Riitsalu, 2018b). It is possible that they have not consciously acknowledged the connection between their financial decisions and FWB. Youth seems to be more keen to invest, and see crypto-assets as a quick path to reaching financial freedom, again, similar to the FIRE movement (Taylor & Davies, 2021). The latter is a concern as they may take unreasonably high risks without adequate understanding of such assets, and their aspirations for reaching financial freedom may suffer as a result.Subjective financial knowledge appears to correlate with investment decisions and with financial well-being. This supports the findings of Riitsalu and Murakas (2019), who discovered that subjective financial knowledge correlates with both financial behaviour and the present component of FWB in Estonia, as well as findings from other quantitative studies in Europe (Lind et al., 2020). Hence, confidence in one’s knowledge about finances is seen to affect FWB, marking an affirmative answer to our fifth research question. Perhaps it is the low confidence in one’s knowledge that is behind the lack of considered planning, saving, and investing indicated above. However, it could be self-rationalisation, a justification for oneself for inaction in personal finances.

Practical Implications

Our study demonstrates how different age groups interpret financial well-being. Younger people distinguished between the three components conceptualized by Brüggen et al. (2017), whereas older respondents only recognised the present and future component without aspirations for financial freedom in the FIRE sense. This has significant implications for the providers of financial services and financial education.Young people need to learn about investing, and sustainable development goals and green finance are of greater importance for them. Banks can emphasise these in their communication and design tools that help them transition from their current lifestyle to financial freedom in the future. Financial education initiatives should place a greater emphasis on the nature of crypto-assets, as well as their risks and opportunities.Middle-aged and older consumers benefit from tools and programmes that allow them to plan and save for the freedom to choose whatever purchases or activities are appropriate for their life stage. They may benefit from saving and investing products that are tailored for specific goals, such as a child’s education or funeral fund. These institutions can assist all consumers in developing confidence in their financial knowledge and taking deliberate action to secure FWB. Financial education programmes should be behaviourally-oriented (Anvari-Clark & Ansong, 2022), rather than focusing on teaching the facts alone.All age groups acknowledged influence from family and peers. Therefore, peer effects can be employed in financial education initiatives (Riitsalu, 2018a), and comparison with "others like you" can be incorporated into the design of personal finance apps and in bank communication. Policymakers need to focus on the digital financial consumer protection matters (Aprea & Bucher-Koenen, 2021; Morgan 2021), especially investing in crypto-assets, as the youth sees it as a key to financial freedom. Also, prevention of fraud needs to be prioritised, as illustrated by one of the older respondents becoming a victim of such a scheme.

Limitations and Future Research

Each study has its limitations. In our case, the sample size could have been larger to reflect the interpretations of a wider group of respondents. However, one should keep in mind the small population of Estonia. Another limitation is that the first two studies employed a slightly different method of data analysis than the third. Third, the data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it impossible to conduct all interviews face-to-face. It is also possible that the health crisis had slightly influenced the perceptions of well-being, but the effects would had been similar across all groups. In ideal conditions, the meaning of financial well-being could be studied in depth when no such global contextual effects occur. However, it does not appear to be possible as we are constantly confronting multiple crises – increasing life costs and energy crisis, the climate crisis, war in Europe, and economic stagnation in developed countries (Burgess et al., 2021). Lastly, the findings from one country may not be generalisable to populations elsewhere, especially considering that FWB is shown to be context-dependent (Brüggen et al., 2017; Fu, 2020; Riitsalu & van Raaij, 2022). Future studies can contribute to this by conducting in-depth interviews using the same methodology in multiple countries simultaneously, comparing the interpretation of FWB across age groups. Such qualitative studies could also focus more on the values and lifestyle choices of individuals to shed light on how these affect the perception of FWB.

Conclusion

Our aim was to investigate the meaning of financial well-being for individuals and how these perceptions and conceptualisations differ across age groups. We found it to be interpreted as keeping the current lifestyle and reaching desired lifestyle in the future, including being able to cover necessary expenses and obligations, and ideally being able to afford anything one desires in the future. For young people, an additional aspiration is to reach financial freedom or independence as promoted by the FIRE movement. For middle-aged and older individuals, financial freedom means a different thing – it is the freedom to earn and spend as one wishes without the expectation of earning sufficient passive income for never having to work again, as the young do. For the oldest group, it also means not being financially dependent on anyone, being able to support children, and having sufficient funds for one’s own funeral. Therefore, we find that the interpretation of financial well-being varies across age groups. These differences suggest that communication from financial sector and financial education initiatives should target the specificities of age groups in their efforts to increase FWB.