Abstract

Email-based fraud is a lucrative market for cybercriminals to scam a wide range of potential victims. Yet there is a sometimes conflicted literature on who these victims are, complicated by low and possibly confounded reporting rates. We make use of an experimental automated scam-baiting platform to test hypotheses about the characteristics online fraudsters find more attractive, gathering behavioural evidence directly from the fraudsters themselves (n = 296). In our comparison of four instrumented ‘personalities’ designed based on traits highlighted in the literature and in a small public perception survey, we find that a script adopting the personality of an elderly woman attracts significantly more engagement from scammers than our control measure. We discuss our approach and the possible interpretations and implications of our findings.

Introduction

Scammers and “con-men” have been prolific in society for hundreds of years, but their impact has been exacerbated by the invention of email. When cyber-enabled, scammers are allowed access to a wealth of potential victims with minimal effort. The techniques used by these scammers range from offering “too good to be true” incentives like a large amount of money or a profitable business deal, to eliciting sympathy in the victim by using emotive language and outlining a difficult situation they are in. These fraudulent schemes are unfortunately highly effective. According to the Scamwatch programme run by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, in December 2022, a total of 6,263,998 AUD from 6,023 victim reports was lost to email-based scams (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 2016). This was echoed in the UK, with over 1.2 billion GBP being lost to fraud in 2022 (UK Finance 2022). Similar severity of loss was seen in the US, with the FBI reporting an increase in the amount lost by victims of cyberattacks, from $6.9 billion in 2021 to over $10.2 billion in 2022 (FBI 2022).A range of different techniques are used to attempt to reduce the effect of email-based fraud, including government guides and public advice on recognising and avoiding scams (Metropolitan Police 2021), content-based email filtering (Yaseen et al. 2021) and blacklisting senders from certain IPs, addresses or domains (Levine et al. 2010). One potentially effective, though controversial, countermeasure is scam-baiting. Scam-baiters attempt to tackle the epidemic of scams by posing as a potential victim and engaging scammers in conversations designed to waste as much of the scammer’s time as possible, with the idea that the scammers are diverted from targeting a victim during this time. While the ethics of some scam-baiting activity is debated (Zingerle and Kronman 2013; Button and Whittaker 2021), the key problem with individual scam-baiters is that their time is also being consumed, and there are far more scammers than scam-baiters. This problem is therefore amenable to a computerised solution.Chen et al. (2023) describe a framework for automatic scam-baiting, in which scammers are randomly assigned to different reply strategies, which engage them in conversation automatically. While originally designed as a means of testing anti-fraud countermeasures, this framework provides a means for direct behavioural experimentation on email-based fraudsters. By carefully designing reply strategies and comparing their performance to control measures, we can use fraudster engagement with different reply strategies as a means of testing hypotheses about what fraudsters find attractive in conversations with their ‘victims’.In this paper, we leverage this approach to tackle a key question in online fraud research from a novel angle: which factors do fraudsters find attractive in potential victims? We create four distinct “personalities” for our reply systems, drawing upon existing literature on the attributes and characteristics that are thought to affect susceptibility to scams, as well as some small confirmatory surveys regarding the public perception of fraud susceptibility. We compare fraudster engagement with these personalities to assess the significance of different factors, such as age, disposition and social support. Most notably, one of the personalities we test is designed on the basis of prior literature suggesting that the elderly can be particularly susceptible to fraud. By comparing the performance of these personalities in real conversations with online fraudsters, we gather evidence on which personalities the scammers themselves believe to be most viable victims.

Background

It is commonly believed that the elderly are more often victims of fraud and financial exploitation, with evidence of them being disproportionately affected by financial scams (Holtfreter et al. 2014), and many papers exploring causative factors (Coombs 2014; Friedman 1992; James et al. 2014). Friedman (1992) explored why consumer fraud disproportionately affects the elderly through a mail survey sent to different police departments, asking for their impressions of characteristics in victims. It was found that women were seen to be more desired as victims than men. Furthermore, being non-married, living alone, or friendliness towards strangers were also commonly identified victim characteristics. Friedman, writing in 1992, does not exclusively cover email-based scams, and some of the factors identified at the time may not be applicable now. For example, access to the victim is a necessary factor for in-person scams, and it may be the case that elderly women were just more physically accessible, rather than psychologically more vulnerable.A review of scams against the elderly by Coombs (2014) outlines a typical victim of financial exploitation as a trusting elderly woman with some cognitive impairment. Elderly women are often more maternal and caring making them more susceptible to emotionally charged sympathy scams. Coombs suggests that they may have outlived their spouse, who might have been their financial decision-maker, considering women’s longer life expectancies. Coombs also argues that a lack of understanding of digital banking, as well as inadequate knowledge of safe internet use, due to not growing up with the technology, leaves the elderly more at risk.Following a survey of older victims of telemarketing fraud, Alves and Wilson (2008) present a different victim profile which includes being male, being highly educated, and divorced. They argue that the victim’s marital status may have some effect because possible loneliness could mean they use phone conversations as some crutch of social support. Furthermore, studies find loneliness to be a predictor for an individual’s likelihood of being scammed (Lichtenberg et al. 2013), and it was found to have a significant effect on older adults’ susceptibility to fraud (Wen et al. 2022). However, other studies find that loneliness is not a significant predictor for engaging with a scammer (Wood et al. 2018). The ‘digital divide’ in security understanding (such as identifying fraud cues) has been linked to socioeconomic status through the mediating factor of social structures spreading security information (Redmiles et al. 2017).A study into the factors affecting susceptibility in older adults without dementia by James et al. (2014) differs from some of the characteristics found by Friedman (1992) and Coombs (2014), instead finding that women are no more susceptible to scams than men are. Additionally, they found that education and income did not seem to have an effect on an individual’s susceptibility. The factors they found that affected vulnerability were poor financial and total literacy, as well as having lower cognition, and poorer health and psychological well-being. There was also a trend of less social support having an effect but it was not found to be statistically significant. However, it has been found that elderly people who socialise more outside of their house are less likely to be financially mistreated (Holtfreter et al. 2014). This supports the idea that loneliness is a factor affecting susceptibility.Lower levels of education have been found in some studies to increase the likelihood of an individual’s intent to engage in a scam (Wood et al. 2018). Titus and Gover (2001), however, found that elderly, and less-educated people are less targeted than younger and better-educated people. Their rationale is that younger and better-educated people may have higher levels of consumer engagement in more varied market groups, increasing their exposure and their likelihood of being targeted. Modic and Stephen (2012) found that higher levels of education corresponded with a higher likelihood of responding to scams. Whitty (2018) also found this, with regard to romance scams specifically. Tackling again the common belief that elderly people are more heavily targeted, Ross et al. argue that the level of fraud amongst older age groups is not disproportionate (Ross et al. 2014). Furthermore, a paper exploring the demographics most likely to fall for phishing scams found the age group of 18-25 to be the most vulnerable (Sheng et al. 2010). Lee and Soberon-Ferrer (1997) found that older, less-educated single adults are more vulnerable to fraud. Lower income was found to be a significant factor only if education was removed from the model, due to the highly correlated relationship between education and income. With respect to the impacts of age and gender, they found that woman over 65 were more vulnerable than men of the same age, but the opposite was true for under 65 s.Gullibility and high levels of trust have been identified in several studies as factors that affect vulnerability (Titus and Gover 2001; Langenderfer and Shimp 2001; Fischer et al. 2013). Laroche et al. (2019) suggest that overly trusting organisations leave an individual more open to scams. Greed is also a factor discussed in several papers to be a characteristic that makes an individual more likely to interact with a scammer (Titus and Gover 2001). Fischer et al. (2013) find that the offering of a large prize can impair decision making. Titus and Gover (2001) also note that being a victim of a previous scam is a powerful predictor of being targeted again, especially considering that lists of successfully scammed victims are sold between scammers (Authority 2008).Additionally, Titus and Gover (2001) remark that victims who display characteristics such as compassion and generosity as well as respect for authority can be more exploited by scammers in certain scams. This is consistent with Friedman’s (1992) findings. Higher levels of agreeableness are found by Modic and Stephen (2012) to be linked to a higher likelihood of responding to a scam. Other aspects of an individual’s personality have also been found to have an effect on their vulnerability. For example, Schulte (1995) points to being easily intimidated as a factor, with scammers alternating their strategies between complimenting and intimidating their targets, some even threatening harm to their targets’ families (Ross and Smith 2011).Whitty (2018) outlines a study where the characteristics of romance scam victims were compared against individuals who had not been subject to a scam. The findings were that middle-aged people were the most likely to fall for a romance scam. Furthermore, contrary to the idea that friendlier people fall for scams more often (Modic and Stephen 2012; Friedman 1992), Whitty found that less kind people were more likely to fall for romance scams. Other predictors found to contribute were impulsivity and lack of control.The general consensus found in the literature is that being older, lonelier, having a lower level of education, and being friendly and trusting are the most commonly identified characteristics affecting an individual’s susceptibility to scams. However, there are tensions in the literature regarding all of these points, with some papers finding the impact of the factors to be insignificant, or claiming the factor has the opposite effect. A good example of this is the typical victim profiles of older fraud victims provided by Coombs (2014) and Alves and Wilson (2008) contradicting each other, as previously discussed. There are also other factors where a common theme in the literature is harder to identify, for example, with the effect of gender in particular being a contentious topic, with findings either not noticing any significant effect (James et al. 2014), or studies finding their results were confounded by other variables such as age (Lee and Soberon-Ferrer 1997), or having studies that find conflicting results.Considering that many prior studies rely on self-reported scam victimisation, the current view of victim vulnerability may be skewed (Schwarz 1999) by the likelihood of each demographic to report scam victimisation, an issue compounded by the general underreporting of cybercrime (Morvareed and Grossklags 2016). Victims may not view their losses as significant, or feel too embarrassed to report the crime committed against them (Goodman and Brenner 2002). Underreporting may also be due to victims believing they possess insufficient evidence, or even fearing for their own safety (Ross and Smith 2011). Disentangling reporting from both susceptibility of victims and selective targeting by offenders is a significant challenge for fraud research. To see past these complicating factors, we design a methodology that allows for different pseudo-victims to engage directly with victims, filling a key gap in this picture by gathering a novel form of behavioural evidence about which victim presentations attract the most engagement from offenders. This evidence, which avoids confounding issues of reporting rates by different demographics, allows us to understand factors which are not only associated with different rates of victim reporting, but with additional effort invested by offenders into offending.

Personality design

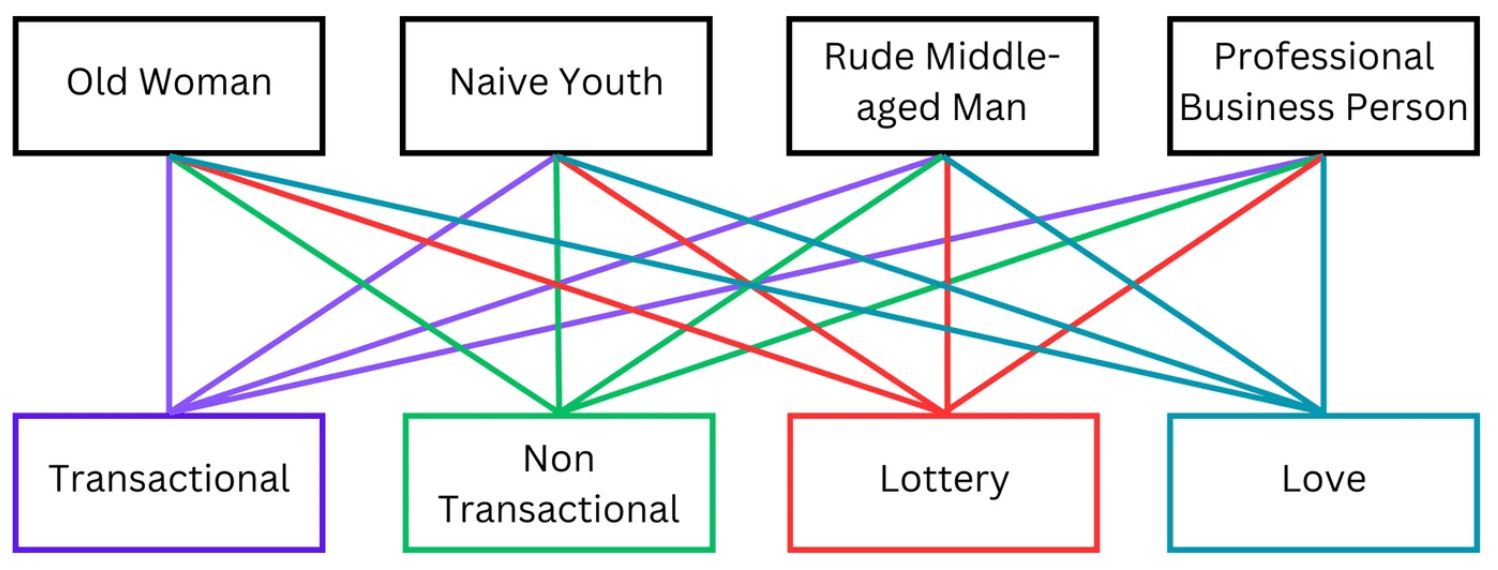

Drawing upon various strands within the literature, we designed four personalities as reply systems, detailed below. Within each reply system, a series of template responses was built to express the personality. These were designed to lead the conversation partner through the anticipated stages of each automatically identified scam format. As the processes of persuasion can differ for different fraud types, each personality reply system contains scripts for handling two general classes of fraud: transactional schemes where the fraudulent premise involves an expectation that the recipient is looking out for their own financial interests, and non-transactional schemes where emotional pleas and other approaches are used in place of financial inducements. To handle specific formats in more detail, scripts were additionally developed to handle lottery and love fraud types, as respective instances of each category. As described in Fig. 1, a total of 16 scripts were developed, involving over 750 email templates designed to represent the intended personalities’ reaction to each scam format.

Fig. 1

Illustration of the different strategies that templates were written for. Four distinct scripts were populated with responses for each of the four personalities

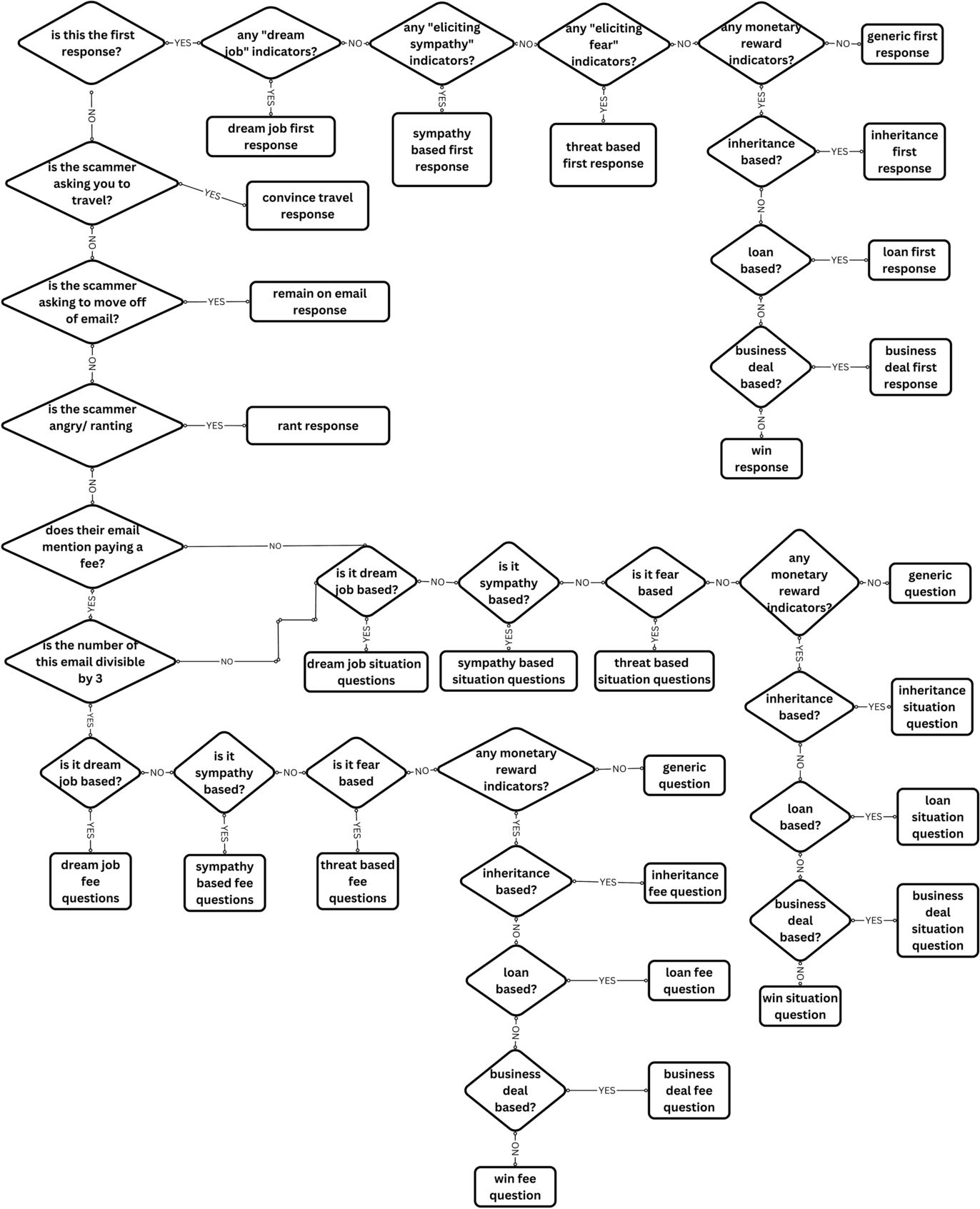

In general, the responses given by the reply systems were determined by the design of the individual personalities, detailed below. However, there were commonalities between the personality reply systems. First, conversations were classified in order to select the correct script to use in response. Second, at each new message, the system attempted to track what stage in the expected scam process the conversation had arrived at using the presence of certain keywords as indicators. Each script included five ‘rant response’ and ‘remain on email response’ templates in order to deal with scammers growing annoyed at the system or attempting to move the conversation to other modalities. The conversation classification also affected the decision process for reply selection under each personality. Figure 2 details this process for the transactional scheme category, which involves identifying possible sub-categories of scheme, sending certain responses only under rare conditions to increase the apparent unpredictability of the reply system, and sending certain responses only once a payment demand has been made, with the aim of simulating a “near win” phenomenon to keep the scammer on the hook, a technique used by Whitty (2013), which may also work against them. Similar processes were designed for each fraud type, with particular attention paid to countering tactics such as time pressure or demands for payment and information.

Fig. 2

A flow-chart depicting the response selection process for transactional schemes. Similar response processes were designed for each fraud format. The actual text of responses also varied for each personality

Ethical considerations Scam-baiting is a sometimes controversial tactic. Many of the ethical disagreements surrounding scam-baiting are due to scam-baiters convincing scammers to send pictures of themselves in embarrassing and degrading situations (Nakamura 2014) for the purposes of public humiliation, or collecting evidence against scammers via illegal means (Zingerle 2015). Therefore, our repliers are not created to be “Trophy Hunters” (Zingerle and Kronman 2013), and do not request any action from the scammers, such as sending embarrassing images, or convincing them to get a humiliating tattoo (Nakamura 2014). Another commonly frowned-upon scam-baiter tactic is to scam the scammers and attempt to get them to send money instead of the supposed victim—none of our personalities attempt this.

Personalities

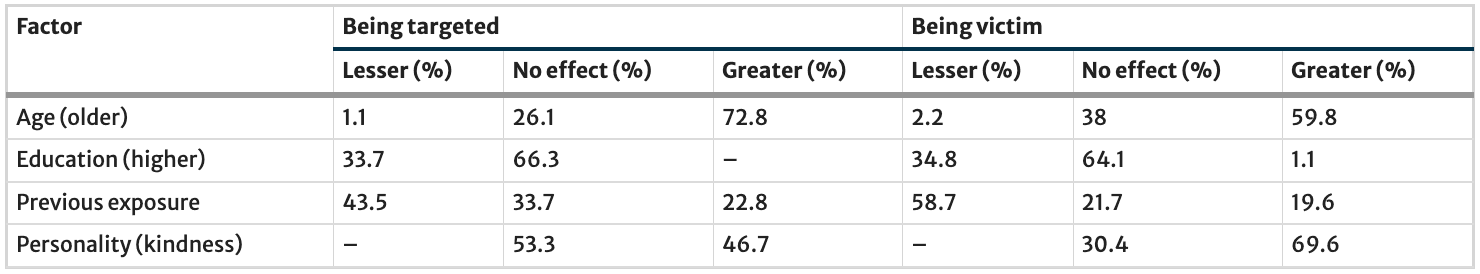

As well as making use of the factors highlighted in the literature, to ground our design of personalities for our response systems, we conducted a public perception survey with a small sample of anonymous participants (n = 92), to identify which factors were considered by the general public to be risk factors in both being targeted by scammers and falling for scams. The results are shown in Table 1. The participants overall considered being older to carry a higher risk of both being targeted and falling victim to online fraud. The most common opinion was that level of education had no effect on fraud victimisation, though no participants considered having a higher level of education to increase the likelihood of being targeted, compared to one third of participants who considered having a lower level of education to increase the risk. Participants mostly believed that never having been exposed to a scam before would make a person more likely to be targeted and fall victim to online fraud, though this item also showed the greatest variation in responses. A person being more kind was always considered to either have no effect or to be more associated with risk of targeting and victimisation, with no participants considering being less kind to be a risk factor.

Table 1 Responses for whether a factor was expected to have positive, negative, or no relationship with either being targeted or being the victim of online fraud (n = 92)

When asked what other factors they believed contributed to increasing an individual’s susceptibility, some common themes arose in participants’ answers. With respect to factors affecting victim’s likelihood to be targeted, common characteristics identified were insufficient technical knowledge, higher wealth, old age and loneliness. Other characteristics often mentioned with respect to increasing a victim’s likelihood to fall for a scam, but which was not mentioned in regard to being targeted, were greed, gullibility and trust.

One theme that differed between the questions about a victim’s likelihood to be targeted versus their likelihood to fall for a scam was that opposite ends of the spectrum regarding an individual’s wealth were perceived to have an effect. The public believe scammers prefer to target the more wealthy. This is intuitive, as they are trying to extract money from their victim. With regard to increasing an individual’s likelihood to fall for a scam, lower wealth is perceived to have an effect. This is explained via individuals in a financially difficult situation being more inclined to take a risk in order to better their financial situation.

On the basis of these results, and the prior literature, template responses were designed for four different personalities, which we assign names as a shorthand. These personalities were as follows: Doris, a kind old woman; Alex, a naive youth; Dave, a rude middle-aged man and Sam, a professional business person. These names were not the names used to sign off their emails in the later experiments, which were chosen using a random name generator, with a parameter for gender being included in the cases of Doris (female) and Dave (male). These personalities were chosen to test a range of factors highlighted from both the literature and our survey as being linked to fraud victimisation, as discussed further below.

Before proceeding to our behavioural experiments, we ran a validation survey to test that our implementation of the personalities in our templates was being perceived in the intended manner. Participants (n=23) were asked to rank various text samples for congruence with the described personality, and provided rich feedback suggesting improvements, as integrated below. Both of our design surveys were carried out under a blanket ethics approval regime, which held as a condition that no information about participants could be collected—as such we do not have detailed demographics of respondents. However, our recruitment methodology likely biassed responses towards a UK undergraduate demographic.

Kind old woman: Doris

Given the strong public perception that old age increases scam vulnerability, the inclusion of an elderly personality was a priority. Doris is designed based around the typical financial victim profile presented by Coombs (2014) of a trusting, caring, widowed elderly woman who has a low level of technological literacy.

Sur et al. (2021) discussed the idea that negative life events increase a person’s susceptibility to being scammed, and even particularly mention widowhood and loneliness, supported by several other sources (Olivier et al. 2015; Lichtenberg et al. 2013; Lawson and Leck 2006). Because of this, Doris was designed as a widow, with attempts to subtly convey this through her templates. In particular, this is mentioned in several of the love templates through use of the phrase “late husband”. However, in the other categories’ templates, where it would be less appropriate to mention her marital status, Doris mentions him only with regard to financial questions (in an attempt to suggest he was her financial decision-maker (Coombs 2014)), for example

What happens if I miss a payment? x Sorry, my late husband used to handle our finances and I’m nervous about messing it up x.

To avoid raising suspicion by introducing the topic of her dead husband, Doris more often mentions her son, and alludes to asking for his advice in 15 of her 193 templates. The aim of this is to subtly suggest she lives alone, is not married, and cannot immediately perform certain actions without help:

That sounds brilliant, x I am so excited, thank you for letting me know. Would you mind explaining to me how to proceed? I’m a bit fuzzy on how to do all this without my son helping me. x

In our public perception survey, technical illiteracy was a factor commonly suggested to increase both likelihood to fall for and be targeted for a scam. Technical illiteracy is implied in some templates, as above, but Doris also explicitly states her struggles with technology in some emails, For example

Am I able to choose how I would like to receive my money, such as a check or wire transfer? I’m just asking as I am not really familiar with all these online banking things and I would need to ask my son for help sorting it all out x.

Another characteristic we attempted to convey with Doris’ personality was compassion, a trait targeted by scammers (Coombs 2014; Titus and Gover 2001), especially in sympathy-based scams like charity scams. We attempt to suggest compassion through the use of kisses (“x”) and common use of terms expressing a mild endearment (e.g. calling the scammer “darling” or “love”). Additionally, Doris is gullible and trusting. This factor is mentioned in Coombs’ (2014) study regarding factors that increase susceptibility in the elderly. It is also mentioned in other literature surrounding scam susceptibility (Titus and Gover 2001; Langenderfer and Shimp 2001; Fischer et al. 2013). Doris (and also Alex, detailed below) is therefore designed to produce more excitable responses to certain prompts, suggesting a gullible enthusiasm:

This is incredible! I never thought this would happen to me. I just wanted to make sure you know how grateful I am x. This money will change my life, my pension has been barely keeping me afloat and this is just what I need! x

The combination of Doris’ gullibility and the allusion to her lower income are intended to make her seem like a viable target, since she has a higher motivation to take a risk to better her financial situation.

When Doris needs to respond to scammer irritation, she is non-confrontational and apologetic. We further lean in to her compassionate traits by calmly requesting patience from the scammer. This exploits the maternal and caring traits traditionally expected of older women (Coombs 2014). An example of one of Doris’ rant responses is:

I apologize if I’m being difficult or frustrating x. I’m not as tech-savvy as I’d like to be, and so if you could please be patient with me and explain things in a way that’s easy to understand, I would greatly appreciate it.

The aim is to diffuse the aggression from the scammer by apologising. Furthermore, it may make them more willing to pursue further conversation if they know they can treat her poorly and she is still eager to continue.

Validation Results The validation survey ascertained whether templates suitably conveyed each personality’s intended identity. The most popular of three example template options was Doris mentioning her son helping her with her banking app, supported in the feedback by multiple suggestions of having a family member to help and mentioning her struggles with technology. Many respondents commented positively on the use of kisses “x” in the emails, as they found it convincingly portrayed text written by an old woman.

The consensus amongst respondents was to use proper grammar and punctuation, alongside an element of formality. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the words she uses, with mentions of using stereotypically “old lady” phrases and terms of endearment such as “love” or “darling”, being suggested, but with cautions against overuse to avoid the personality sounding like a caricature.

Naive youth: Alex

To explore the other end of the spectrum regarding age’s effect on scammers' interest, we included a youthful personality. While the elderly are usually perceived as being more vulnerable, Titus & Gover claim that younger people are actually more targeted for scams (Titus and Gover 2001). Furthermore, Sheng et al. (2010) found that the most vulnerable demographic was younger people. As younger people are more often stereotyped as naive, this was a natural additional factor to include in Alex’s design.

The concept of naive optimism is the idea that someone views opportunities as more likely to have a positive outcome rather than negative. As Zakay puts it, “naive optimism is a potential hazard for decision making optimality” (Zakay 1990), which ties in with the idea that scammers try to encourage poor decision making (Carter and Brown 2020). Optimism is shown in Alex’s emails through consistent use of smiley face emoticon “:)”. Furthermore, particularly in the lottery scam, excitement and optimism (alongside gullibility) is shown:

just wanted to say thank you this is soooo cool:)))))

Following a suggestion from the validation survey, in some templates Alex mentions needing their father’s help, but not wanting to ask for it. This indicates a self-imposed removal of their own social support system, presenting themselves as more vulnerable, therefore hopefully increasing the scammer’s motivation for pursuit. A lack of social support has been shown to have an association with increasing scam vulnerability (Alves and Wilson 2008).

i don’t really understand bank transfers, i can ask my dad but i would rathar he didnt know about this.

Though spelling and grammatical errors provide no real indication of the intelligence of a person, we have used them in an attempt to further imply naivety or a lower education level, which has been found to increase an individual’s intention to respond to scams (Wood et al. 2018). In particular, note the lack of capitalisation used in Alex’s templates, this is done in an attempt to show their youth, as it has been observed that younger people tend to use lowercase even when it is not grammatically correct (Merrilees 2020).

When faced with scammer irritation, we attempt to convey that Alex is easily intimidated, as Schulte (1995) mentions intimidation as an increasing factor in his paper regarding susceptibility to telemarketing fraud. Although our context is email rather than telephone scams, intimidation is not uncommon, and compliant behaviour may be attractive to scammers:

i’m sorry please don’t be angry at me i will try and understand more quickly :( please dont shout at me or be angry.

Validation Results For Alex, the lowest ranked template was a formally written template, and the highest was casually written, and included an emoticon “:)”. When asked what aspects of the templates they thought were effective with respect to the template being convincingly written in Alex’s voice, several common suggestions arose. One of these suggestions was to use casual text, “chatty vocabulary” and colloquialisms. There were some disagreements in the responses as to how to effectively utilise punctuation, with some respondents liking the use of lots of exclamation marks, and others suggesting the amount being used was over the top, and to use less. Another point that several respondents disagreed on was whether emoticons or emojis should be used: we decided to use emoticons, since these were present in the top-ranked example template. A key suggestion was to display naivety and youth by having Alex mention asking their parents for help.

Rude middle-aged man: Dave

The personality of Dave is closely modelled around the typical profile of a romance scam victim presented by Whitty (2018), of a less kind, impulsive, middle-aged individual. He displays many of the opposite traits to those Doris displays. For example, he is rude instead of friendly, sceptical instead of gullible, and male instead of female. Furthermore, he lies in the middle of the age scale, as compared to being at one of the extreme ends, like Doris or Alex.

Dave was designed to explore the idea that annoying the scammer may make them more inclined to persist with the victim in order to get some form of vindication; however, this tactic also runs the obvious risk of the scammer giving up quickly if they perceive Dave as too stubborn and not worth the effort. Greed was one risk factor suggested in the public perception survey, and there is some support for this idea in the literature (Titus and Gover 2001; Fischer et al. 2013). Therefore, we attempt to display Dave’s greed in his templates through his curt, demanding manner of speaking. However, sometimes the content of his templates also gives a direct indication of his character. For example, if he is asked to send money to cover a fee, one of Dave’s responses is simply:

Can’t you put your own money in?

Furthermore, the use of imperatives and short, snappy sentences in Dave’s templates are supposed to convey an arrogant and entitled tone.

I don’t like the current solution we have arrived at. Make it better

Unlike Alex and Doris, Dave chooses a sceptical response rather than an excited response every few messages, for example:

Don’t bullshit me. if you are lying I will not send this fee.

The use of expletives further displays Dave’s rudeness, alongside his disrespect for the scammer. This confrontation may result in aggression from the scammer. This could possibly enrage them enough to be more determined to con Dave out of money, drawing out the conversation, and wasting more of the scammer’s time. In order to try and make Dave seem heartless, if our system detects signs of a sympathy-based scam, Dave will respond with an unsympathetic, self-interested response (in contrast to Doris and Alex, who submit sympathetic responses). For example:

Why are you messaging me about this?

When responding to scammer irritation, Dave’s templates have to be rude. One interesting piece of advice discussed in scam-baiting forums is to rant back at the scammer, as this often provides interesting responses (Al 2022). The issue the author outlines is that the scammer’s behaviour is unpredictable. They might abandon the conversation; however, it may enrage them enough to be more determined to scam Dave. These rant responses are rude, fully capitalised and contain many expletives. Furthermore, some templates threaten to terminate the conversation, this may make the scammer panic and apologise, or rant back again. One example is

DO NOT TALK TO ME IN THAT TONE. YOU WILL RESPECT ME AND I WILL STOP EMAILING YOU IF YOU DON’T TREAT ME WITH SOME FUCKING RESPECT. YOU NEED TO LEARN A LESSON YOU FUCKING IDIOT.

Validation Results The respondents’ first choice of example template for Dave contained short sentences, and the use of imperatives to convey an assertive tone. Most of the comments about the effectiveness of the templates dwelled on these features, i.e. responses such as “Arrogant text”, “Very direct, not very enthusiastic and not particularly polite.”, “short snappy sentences and quite demanding”. A key correction from participants was to not to use exclamation marks in Dave’s templates.

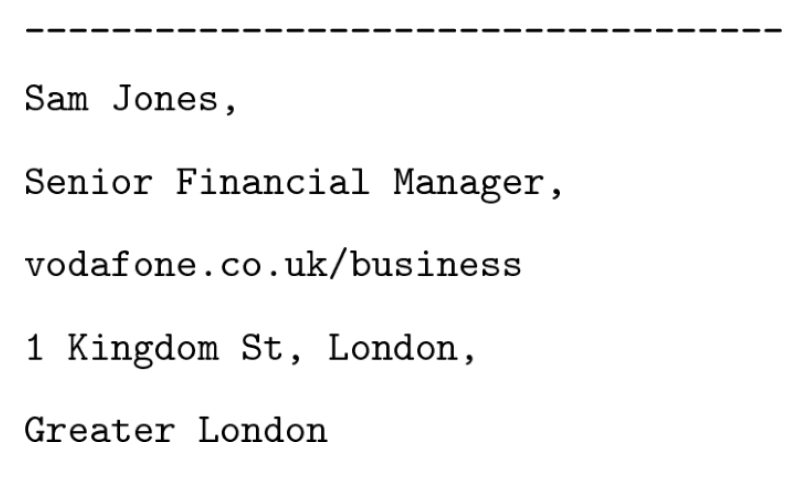

Professional business person: Sam

The motivation behind including a professional business person personality is that being perceived as a professional with greater access to disposable income is likely to be very attractive to scammers. A high level of education has been identified as a common factor in scam victims (Alves and Wilson 2008), it was found to increase an individual’s likelihood of responding to scams (Modic and Stephen 2012), and younger and more educated people often fall into a larger group of demographics and can be targeted more (Titus and Gover 2001). These traits were a natural fit for Sam. It is difficult to try and portray a high level of education over email, but we attempted this using formal sentence structures with correct grammar:

I’m sorry, could you please explain again about the necessity of this payment? I don’t recall being notified about it before now. Do you have any records of previous contact being made with me?

This template also implements a piece of advice taken from survey respondents, to ask for more details and reassurance from the scammer. The inclusion of these detailed questions could lead to longer conversations with the scammers. Sam’s high level of education is further implied by markers that they have an important role in an established company. This was conveyed through a signature appended to each email, which many respondents in the validation survey were pleased with:

Additionally, when the scam is identified as a dream job scam, it is appropriate for Sam to mention their high level of education, as seen here:

What qualifications are required for this job? I have a bachelors in Economics from the University of Exeter and 10 years experience in the working world.

At the stage in lottery scam conversations where our personalities reply with either a sceptical or excited response, Sam replies with a sceptical response, however they are not as rude as Dave. An example of this template is:

I’m not sure how I could have won the lottery without entering. Could you provide more information about how this is possible?

There is a special case with Sam’s sign off when compared with the other repliers, as they are the only replier to sign off with both their first and last name, as a marker of formality. When handling scammer irritation, Sam tries to mitigate the situation by politely demanding respect, but also showing that they are not intimidated by the scammer:

I appreciate you may be frustrated, but I would appreciate it if you could express this in a respectful way. It’s important to me that we communicate in a professional and constructive manner.

Validation Results Many respondents had a very positive response to the use of a signature in Sam’s emails, with 17 of the 23 participants ranking the template containing this to be the most appropriate. Other aspects commonly suggested by respondents were the use of formal language as well as good grammar. Another suggestion was to have Sam ask for reassurance and further details.

Scam-baiting experiment

With each personality-based reply system implemented as responder modules within (Chen et al. 2023)’s framework, and following initial testing, we ran a one-month experiment in which the system contacted real online fraudsters, assigning each of them to an attempted conversation with either one of our automated personalities or the control measure, which was Chen et al.’s random-response ‘Classifier & Template’ module. The system ran at slightly variable times in two hour intervals, to avoid any suspicious regularity in responses to fraudsters. Sending was also rate-limited to avoid any concerns from our mail delivery provider. Our study was approved by our institutional ethics review board (approval number 13740), with oversight of our experiments involving human subjects.Following the completion of the study period, conversation logs were sanitised by removing any conversations facilitated by an automated replier on behalf of the scammer—as we are interested only in evidence of sustaining a human scammer’s interest. Conversations containing more than two duplicate replies (n=12) were flagged for manual review to determine if the scammer side of the conversation appeared automated. Excluding such automated conversations, the system overall had interactions with 296 different scammers, receiving total of 1416 replies from them. Of the 296 successful conversations, 203 were transactional, and 81 were non-transactional. There were only 9 lottery and 3 love emails encountered in the study period.We compare the performance of reply systems in terms of both their reply initiation rate—the number of times they managed to start a conversation with a scammer—and their conversation length: the number of replies they extract from a scammer after having started a conversation.

Reply initiation rate

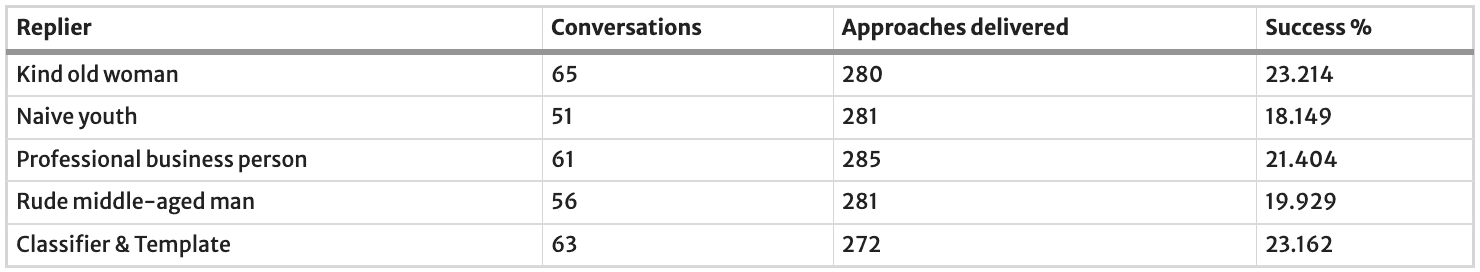

Table 2 shows the number of conversations initiated per approach made. While the scam-baiting framework should assign approximately equivalent numbers of scammers to each reply system, some approaches can fail due to, for example, the email bouncing because of action taken by the email provider to stop the scammer. Therefore, the ‘approaches delivered’ column counts the non-bounced approaches made by each personality. Overall, the system received an initial reply from the scammer 21.2% of the time. Interestingly, several of the personalities performed worse at attracting scammer responses than the control measure, with the exception being Doris, who performed slightly better. However, a -test found no significant difference in initiation rates , failing to reject the null hypothesis of approximately equivalent initiation rates.

Table 2 The number of conversations initiated per replier

Conversation length

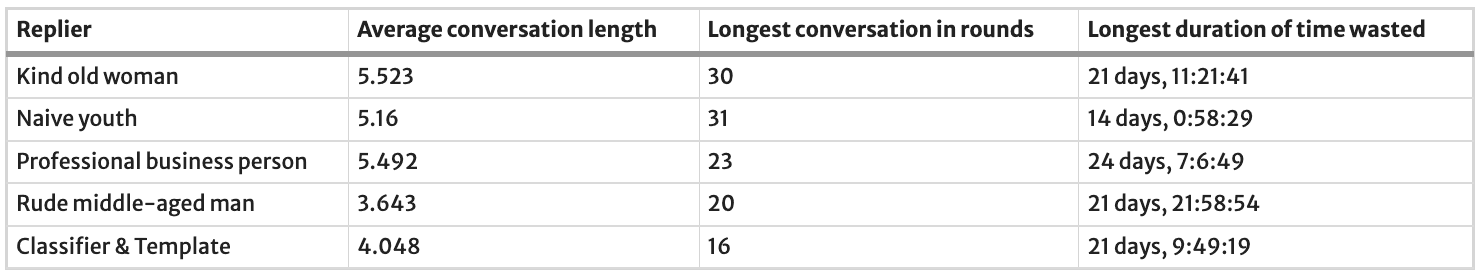

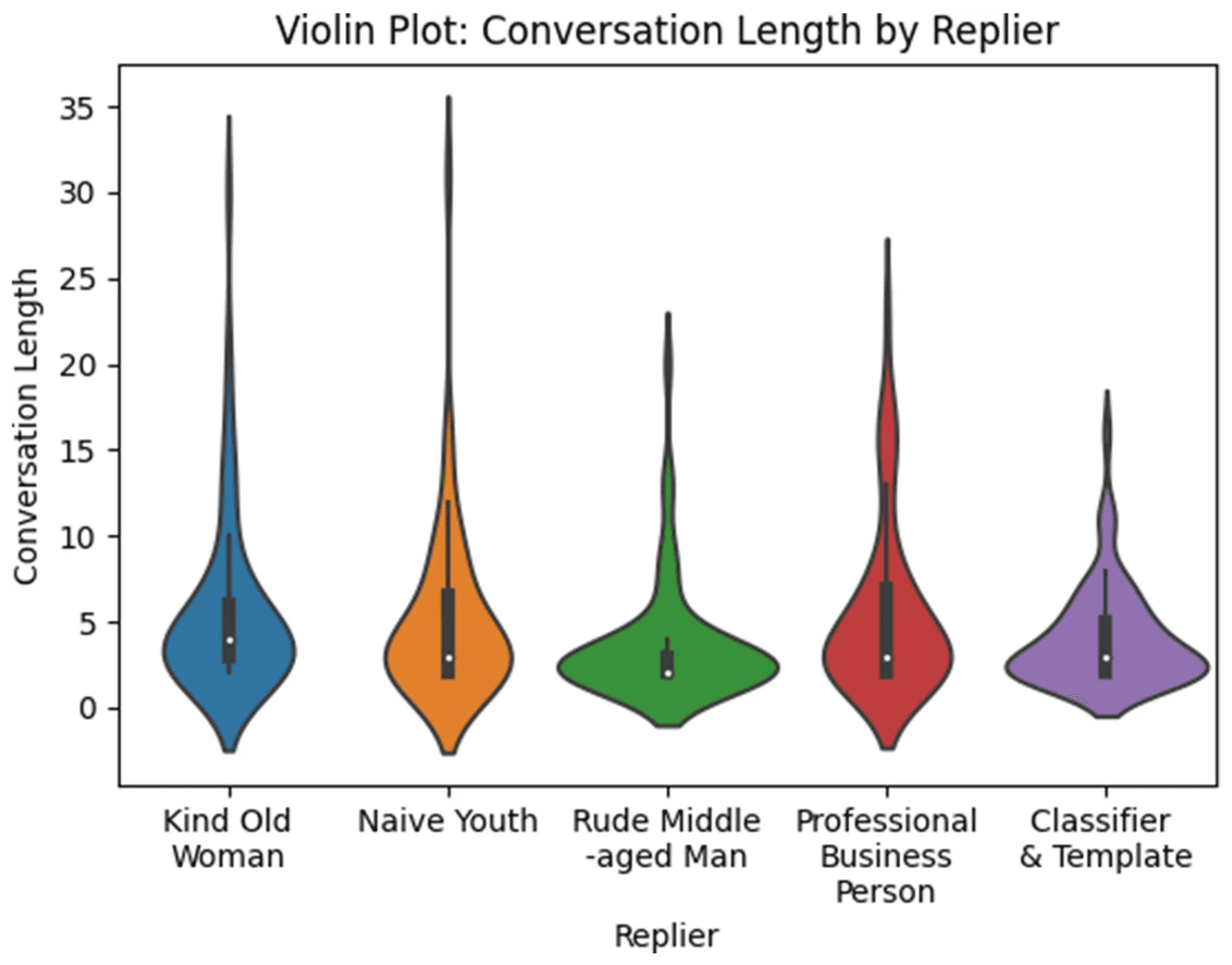

The longest conversation by any personality was 31 rounds of conversation, which was achieved by Alex. This was followed closely by Doris, whose longest conversation lasted 30 rounds of conversation. Notably, these were a lot longer than the longest conversations had by the other personalities or the control measure, as shown in Table 3. As also illustrated in Fig. 3, Doris had the highest average conversation length with scammers. The only personality to under-perform relative to the control was Dave.

Table 3 Information about the length of baiting conversations

Fig. 3

A violin plot to show the distribution of data with respect to conversation lengths per replier

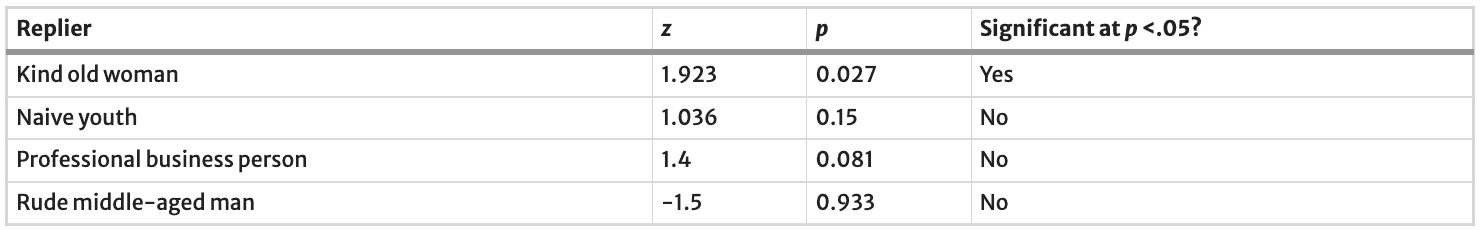

A one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test was performed comparing the conversation length performance of each personality against the control measure. The Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric statistical test, was chosen because the Anderson Darling normality test showed the conversation length data were non-normal. The results are seen in Table 4. Surprisingly, the only personality that displayed a statistically significant increase in conversation length when compared against the classifier & template replier was Doris. However, failure to reject the null hypothesis for other personalities could be due to a lack of statistical power, and comparisons in an experiment obtaining more conversations could be beneficial.

Table 4 Mann–Whitney U test results for each personality against the classifier & template replier with regard to conversation length

Discussion

Out of all personalities, the only personality that performed significantly better than the control for conversation length was Doris. We expected Doris to be the best-performing personality, as she was designed to closely mirror the most common characteristics that arose in both the literature and the public perception survey. Given that the elderly are reported to be disproportionately affected by scams (Holtfreter et al. 2014), and there is a large body of literature on factors that may contribute to this (James et al. 2014; Coombs 2014; Friedman 1992), it does not surprise us that behavioural evidence from scammers confirms they are significantly more engaged in conversation with an automatic system designed to resemble an elderly woman.With regard to the effect of age on the scammer’s likelihood to pursue a target, Doris and Alex elicited the longest conversations. It could be the case that age is an increasing factor on both ends of the spectrum—an interpretation supported by the poor performance of middle-aged Dave. However, this difference in performance could also be indicative of friendliness and gullibility being significant factors, as these are traits in common between Alex and Doris, and Dave displays in general opposing personality traits.Sam was arguably the second-best system in our experiment. This could be due to the polite but professional tone of the emails, and the email signature, convincing the scammer their target has a stable job and disposable income. Dave, the worst performer, may have suffered because he was designed around the victim profile provided by Whitty (2018) for typical romance scam victims. The victim profile for romance scams is very different to the generally accepted profile of other scam victims. Since there were only 3 love schemes identified in our study, this may have affected Dave more severely.For each replier, a large proportion of the conversations are short with less than 5 rounds of replies, with the median conversation being fairly short and a substantial number of the conversations falling between receiving 5 replies or less. This could suggest that many scammers do not view the personalities as viable enough targets to pursue (Herley 2012), and that there is room for further improvement to make the automated responders more convincingly human. However, the skew towards shorter conversations could also be because many conversations were still being started as the experiment was coming to an end, and some scammers take longer to reply to approaches. A longer study period could help identify these issues in more detail, and we would especially recommend including a tapering-off process to avoid the system approaching new scammers towards the end of the study.Our approach suffers from some key limitations. The design of personalities is not a straightforward exercise and necessitates some mixing of multiple factors, complicating interpretations of our findings. Further, the designs are influenced by our own cultural biases, and scammers not from the same cultural background may not have interpreted the identity cues in the way we intended. For example, Doris was closely designed to mimic the quintessentially English grandmother, and tested against a likely predominantly English audience, and aspects of this personality may not be understood to a scammer who has not been exposed to this stereotype.At a more practical level, the template-based methodology of personality design scales broadly—it engages many scammers and can do so simultaneously—but not deeply, as scammers will eventually exhaust the template responses, leading to repetitions that eventually will reveal that the personality is not human. Information-sharing between scammers could also lead to particular personalities being recognised in the future, limiting their reuse value as points of comparison. Alternative approaches to creating more dynamic ‘personality’ reply systems could avoid this limitation.

Interesting scammer behaviour

As our study mechanism gives us rare access to the communications of scammers in mid-conversation, we highlight below some of the interesting behaviours observed in our transcripts.The Irritation Stage A key motivation for manually reviewing conversations containing duplicate message was that we noticed (presumably) human responders getting annoyed and then proceeding to send short one-word duplicate emails. For example, the longest conversation had by the classifier & template replier ended with multiple emails that just read “ok” or “,”. This may have been the result of a scammer identifying that they were talking to a bot, or due to irritation from repetitive questions. We saw multiple examples of such irritation, largely provoked when the automated systems ran out of unique template responses:

“How are you repeating one question or the other. How many times will you ask a question?.Are you kidding me or what? Have a nice day” Scammer A

“You have ask this question. Before and I assured you and you keep repeating same question, Well I assure you 100%.” Scammer C

“We are not going to take any further question from you, especially questions that have been answered repeatedly. When you are ready to follow the process to claim your winning (prize) then do the needful by providing your details, and you have till Friday 25th March to do that, otherwise we may have to terminate your payment without any further consideration, and a fresh raffle draw will be conducted for another participant to take your slot.” Scammer E

Notice in the last example, the scammer responds to our time-wasting with attempts to introduce new time pressure, introducing a false deadline. From this feedback, we suspect that the repetition of questions is prematurely ending conversations, and an immediate improvement to the system could be to increase the bank of templates for each category. A longer-term solution could be to switch to text generated content (see e.g. Bajaj and Edwards (2023)) once manually written templates have been exhausted and a solid pretext has been established for the pretend victim. This would help in avoiding exact copies of emails being sent.Flattery Another interesting behaviour displayed by some of the scammers was their inclination to heavily compliment their victims. This could be a method of weeding out non-viable victims, as the people most susceptible to flattery are “unsuspicious and trusting” (Eylon and Heyd 2008). This may be one of the reasons that gullibility and trust are commonly identified to be factors that increase vulnerability to scams. Several examples of the flattery used by scammers can be seen in the following email excerpts:

“According to the email i received from you, i must say thank you very much, for your high sense of maturity, intelligence, experience and understanding displayed on your email” Scammer F

“my brother,my heart is full of joy .Insha Allah I will always love you and your entire family.you have truly proved to me that you are a man of your word and very honest man” Scammer G

“Thanks for your kind response to my email, I am so much appreciated. PLease note business is 100% risk free and I also believe that you are a kind person who can take care of my daughter very well once you have my late husband’s money received in your account.” Scammer H

This is not a Scam In some of the conversations, the scammer makes an explicit statement about not being a scammer. This may seem like an obvious indication to most people that the conversation is not legitimate, and it could again be a way to weed out less gullible targets. Some examples of this can be seen in the following excerpts:

“I’m not a scammer as you think. And the reason why some people were scammed before now. Is because they deal with the wrong people on the internet and not real people like this consignment package.” Scammer I

“This is just to inform you that the deal I want to do with you is100% risk free provided that we can trust each other, be sincere with each other and keep it confidential.” Scammer L

Also note that Scammer L makes a specific effort to tell their victim to keep their communication a secret. If the victim’s family member or friend is told about their plans, they may be able to more easily identify the fact that the scammer is defrauding the victim and let them know. This victim-isolating behaviour coheres with explanations for the factors of low social support and loneliness increasing scam vulnerability (Lichtenberg et al. 2013; Lawson and Leck 2006; Holtfreter et al. 2014; Sur et al. 2021). We saw this isolating behaviour several times in other contexts:

“The third was I demand you keep our involvement secret because if the office comprehends I was assisting for a monetary compensation I will be punished.” Scammer M

“Please my services you keep secret to yourself and follow my legal step as I will provide to you the bank processing form which you fill to return for your due payment.” Scammer N

Scammers Presenting Themselves as Trustworthy Scammers will often make an effort to explicitly state that they are trustworthy, and claim to have other positive qualities. This may be a shortcut for the scammer to establish a positive rapport with their victim, a method of grooming them. Examples of their self-promotion can be seen in the following excerpts:

“I want to assure you of the success of this transaction and that you will not regret doing this with me. First of all, it is important that you know that the basis of this transaction and my relationship with you is 100% TRUST.” Scammer P

“To be candid with you, I cannot be here wasting my time and yours if this is not true, I am too religious for that, you have absolutely nothing to worry about. I will equally take some step further to allay your fears that you have nothing to fear.”“I really have to say this to you, I am a born again Christian which i believe you are, but I have to still assure you here that you are dealing with a responsible man and of high integrity.” Scammer R

Note how in some responses, the scammer paints themselves as religious. Edgell et al. (2006) found that religious people are perceived to be more trustworthy, possibly due to them being associated with a high level of morality, this is supported by Moon et al. (2018), also finding religious people are more trustworthy, especially to other religious people. In future personality-based scam-baiting experiments, this could be explored experimentally through the provision of a ‘devoutly religious’ personality-based reply system.

Implications and future directions

Our findings suggest that, at least within the forms of email-based fraud tackled by our system, certain conceptions of the ‘ideal’ or ‘typical’ victim from previous fraud research do not provide the expected response from online fraudsters. Most notably, the personality of Dave, designed to resemble the typical romance fraud victim according to Whitty (2018), was one of the worst performers, suggesting that, at the least, the romance fraud victim profile does not generalise to other forms of online fraud. However, presenting a believable personality to scammers necessarily involves including multiple facets, complicating analyses. Our framework allows for research questions to be refined on the basis of behavioural responses from scammers, suggesting a number of directions for future experiments.One example of more directed experimentation would include comparison of different personality facets while holding some factors of interest constant. For example, the personality of Doris could be contrasted with other personalities that also present as elderly, allowing us to extract behavioural evidence about which signals make online fraudsters more or less interested in engaging with an elderly person, informing more specific preventative campaigns. Our insights from these conversations can also help identify new factors for similar comparisons—the identification of religion as a characteristic of interest to scammers suggests the possibility of an experiment comparing personalities designed to signal different religious backgrounds or degrees of religiosity.

Conclusion

Our automatic scam-baiting reply system designed around a kind old woman personality profile was shown to have a statistically significant increase in conversation length as compared to the control system. At a technical level, this gives us reason to believe that automated systems comprising of repliers following personality briefs and established conversation structures could be an effective countermeasure for email-based online fraud.More particularly, our result provides behavioural evidence that scammers are more likely to engage and persist with targets they believe are elderly. The directness of this evidence, which does not rely on a scam being successful or being reported, helps to avoid confounding factors that have plagued previous studies: our finding cannot be directly attributed to the elderly being more likely to report scams, or more likely to fall victim. The implications of this being that perhaps more specific and effective countermeasures for fraud could be deployed. For example, directed teaching resources for the elderly to increase technological competency and knowledge of scams.However, the design of personality profiles is necessarily multifaceted, and other factors in Doris’ profile may be more significant than her age alone. We present this result as an example of how technology facilitates novel experimental approaches to understanding and countering online fraud.