Abstract

Financial abuse is a significant form of elder maltreatment and is frequently ranked in the top two most common forms of abuse perpetration. Despite this, it is under-identified, under-reported and under-prosecuted. Financial institutions, such as banks, are important environments for identifying and responding to the financial abuse of older people. Traditionally, banks have not always been part of inter-sectorial responses to financial abuse, yet are important stakeholders. The aim of this study is to explore perceptions and experiences of financial abuse in five national banks. Data were collected from 20 bank managers and five members of the National Safeguarding Committee in the Republic of Ireland. Using thematic analysis, four themes were identified: defining a vulnerable adult; cases of financial abuse of vulnerable adults; case responses to financial abuse of vulnerable adults; and contextual issues. The data demonstrate the multiplicity of manifestations and the complexity of case investigation and management. Findings point to the need to enhance banks’ responses, through additional education and training, and promote integrated inter-sectorial collaboration. In addition, a change in societal beliefs is needed regarding financial entitlement, responding to ageism, public awareness of the consequences of financial decisions and types of financial abuse, as well as ensuring such crimes are addressed within the legal system.

Introduction

Research, practice, policy and legislation within the domain of elder abuse have increased significantly in the last decade. The Toronto Declaration adopted Action on Elder Abuse's (1995) definition, stating that:Elder abuse is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person. (World Health Organization and INPEA, 2002: 2)Elder abuse has generally been viewed using particular typologies, most commonly emotional/psychological abuse, financial/material abuse, sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect. In more recent years, there has been a framing of elder abuse within human rights approaches (Lowenstein and Doran, Reference Lowenstein, Doran and Phelan2020; Phelan and Rickard-Clarke, Reference Phelan, Rickard-Clarke and Phelan2020; Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Lindberg, Zhao and Phelan2020), with concurrent legislative and policy development which centralises the principles of autonomy and self-determination balanced with supporting and protecting older people to live safe lives.

There is a plethora of research on the prevalence of elder abuse (O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Hills, Doyle, McCreadie, Scholes, Constantine and Erens2007; Laumann et al., Reference Laumann, Leitsch and Waite2008; Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010; Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Treacy, Lafferty, Lyons and Phelan2010; Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc. et al., 2011; National Institute of Care of the Elderly, 2015; Sandmoe et al., Reference Sandmoe, Wentzel-Larsen and Hjemdal2017). A study by Yon et al. (Reference Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis and Wilber2017) identified a pooled prevalence of 15.7 per cent (52 studies) in community-dwelling older people. In Ireland, where old age is considered 65 years and older, a national prevalence study (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Treacy, Lafferty, Lyons and Phelan2010) found that financial abuse was the most frequent perpetration of abuse. Equally, the Irish state's national health service, the Health Service Executive's (HSE) annual safeguarding reports, demonstrate financial abuse as a common finding in its case investigations (National Safeguarding Office, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020). However, although the financial abuse of older people is an increasing research focus, there is a dearth of studies that have examined this area in the context of financial institutions’ experiences.

Financial abuse

Over 40 definitions of financial abuse have been identified (Fealy et al., Reference Fealy, Donnelly, Bergin, Treacy and Phelan2012), which contribute to blurred understandings of the phenomena; this makes prevalence and research comparisons challenging as well as limiting the transferability of policy and practice response directions (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Cairns, Davies, Harries, Gilhooly and Notley2013; Jackson, Reference Jackson2015). The majority of definitions describe financial abuse as involving monetary abuse, property abuse or legal abuse (Vancity, 2014). In Ireland, financial abuse has been defined by the HSE:Financial or material abuse includes theft, fraud, exploitation, pressure in connection with wills, property, inheritance or financial transactions, or the misuse or misappropriation of property, possessions or benefits. (HSE, 2014: 9)In 2011, a Metlife Study identified that financial abuse of older people in the United States of America (USA) was estimated to cost at least US $2.9 billion, however, this is likely to be an underestimation (Deane, Reference Deane2018). Figures in the USA may be as high as US $36.5 billion (Truelink, 2015; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2019), when financial abuse, criminal fraud and care-giver financial abuse are combined. In Ireland, while there is evidence of financial abuse of older people through HSE safeguarding reports (National Safeguarding Office, 2017, 2018, 2019) and comments in a recent Issues Paper (Law Reform Commission, 2019), its scope and volume has not been quantified and, similar to other countries, a true estimate is elusive (Phelan et al., Reference Phelan, Fealy, Downes and Donnelly2014; Wood and Lichtenberg, Reference Wood and Lichtenberg2017; Deane, Reference Deane2018). Modes of financial abuse perpetration are multiple (Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Fairman, Rosen and Wilber2011; Dalley et al., Reference Dalley, Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Levi and Harries2017) and may occur without the knowledge of the older person, yet have devastating impacts such as loss of confidence to live independently, distress, or mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Rossall and Hart2015). Similarly, the loss of fiscal resources can constitute a threat to the economic security of the older person (Greene, Reference Greenein press), while any return to financial stability may be limited as older people do not have the same capacity to re-enter the workforce (Hafemeister, Reference Hafemeister, Bonnie and Wallace2003).

An increasing population of older people, ageism, growing numbers of people living with dementia and the fact older people tend to have assets compared to younger generations render them an easy target for exploitation (Canadian Foundation for Advancement of Investor Rights and Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2017; Phelan, Reference Phelan and Phelan2020). Financial abuse may manifest as theft and scams, signs of financial victimisation, financial entitlement, coercion and money management difficulties (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Levin, Gagin and Friedman2007). Dalley et al. (Reference Dalley, Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Levi and Harries2017) suggest this can present as situations where the abuser has charge of the older person's finances or he or she uses manipulation to exploit the person financially or engages in deception. Perpetrator motivations can be malicious (not spending assets for the wellbeing of the person or using assets for own use), or be due to misplaced moral justification, opportunism, neglect or incompetence (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Dalley, Gilhooly, Sullivan, Harries, Levi, Kinnear and Davies2016).

Prevalence studies on financial abuse are mixed. In Israel, a study of older people admitted to two hospitals indicated a prevalence rate of 8.9 per cent in patients over 70 years (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Levin, Gagin and Friedman2007), while Peterson (Reference Peterson, Burnes, Caccamise, Mason, Henderson, Wells, Berman, Cook, Shukoff, Brownell, Powell, Salamone, Pillemer and Lachs2014) identified a one-year prevalence rate of 2.7 per cent and a lifetime prevalence of 4.7 per cent. In the United Kingdom (UK), it was estimated that over five million older people have experienced scams alone (Age UK, Reference Age2017). Although Yon et al. (Reference Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis and Wilber2019) suggest a global prevalence of 3.8 per cent, financial abuse remains under-researched, under-recognised and under-prosecuted (Jackson, Reference Jackson2015; Feng and Lee, Reference Feng and Lee2018; Lloyd-Sherlock et al., Reference Lloyd-Sherlock, Penhale and Ayiga2018; Phelan, Reference Phelan and Phelan2020; Gorney et al., Reference Gorney, Cassidy-Eagle and Smith2020). It is estimated that only one in six cases are referred to formal services (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Cairns, Davies, Harries, Gilhooly and Notley2013; Canadian Foundation for Advancement of Investor Rights and Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2017), pointing to the need to have professionals in multiple settings alert to identifying and reporting such abuse. There may be a lack of knowledge of being abused, e.g. when an older person has entrusted their finances to another person (i.e. Power of Attorney, through joint accounts) or if a cognitive challenge has impacted comprehension of such acts. In addition, the older person may be under undue influence to part with finances or be reluctant to report a close relative (Phelan, Reference Phelan and Phelan2020). Other non-reporting factors include embarrassment as well as fear of retribution by the perpetrator. Where the victim is dependent on the abuser, a concern regarding the potential loss of support with day-to-day activities or social connection may be perceived (MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2011; Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Rossall and Hart2015).

Risk factors for financial abuse include ageing and cognitive decline (Pinsker et al., Reference Pinsker, McFarland and Pachana2010; Lichtenberg et al., Reference Lichtenberg, Ficker, Rahman-Filipiak, Tatro, Farrell, Speir, Mall, Simasko, Collens and Jackman2016; Storey, Reference Storey2020), requiring assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) (Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Burnes, Caccamise, Mason, Henderson, Wells, Berman, Cook, Shukoff, Brownell, Powell, Salamone, Pillemer and Lachs2014) or instrumental ADLs (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Schulz, Castle and Rosen2010), gender (O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Hills, Doyle, McCreadie, Scholes, Constantine and Erens2007; Soares et al., Reference Soares, Barros, Torres-Gonzales, Ioannidi-Kapolou, Lamura, Lindert, de Dios Luna, Macassa, Melchiorre and Stank2010), emotional vulnerability or loneliness (Fenge and Lee, Reference Feng and Lee2018), living alone and socio-economic group (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Treacy, Lafferty, Lyons and Phelan2010), ethnicity (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Burnes, Caccamise, Mason, Henderson, Wells, Berman, Cook, Shukoff, Brownell, Powell, Salamone, Pillemer and Lachs2014) and negative social interactions (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wood, Xi, Berger and Wilber2017). A smaller social network and higher perceived social support are proposed as providing protective factors (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Schulz and Sneed2016), as well as the quality of the relationship with the older person (Wilber and Reynold, Reference Wilber and Reynold1996; Kemp and Mosqueda, Reference Kemp and Mosqueda2005).

Within traditional approaches to safeguarding older people, response services to financial abuse have been structured around health and social care services, particularly within the public service domain. Financial abuse case management can be complex and may involve navigating issues related to decision-making capacity, poor inter-agency collaboration and a lack of evidential proof (Dally et al., Reference Dalley, Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Levi and Harries2017). Prosecutions for financial abuse are not common and this may be due to issues such as family ties, misplaced beliefs of entitlement, embarrassment, a perception that this would indicate a lack of ability to cope, trust in the authenticity of the person (particularly in scams), a blurring of legitimate transactions and a bargaining for some advantage, such as family visits or access to grandchildren (Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Iris and Ridings2009; Phelan, Reference Phelan and Phelan2020). Unlike other forms of abuse, financial abuse can occur remote from the older person and involve non-health and social care services, such as financial institutions, and may be perpetrated without the victim's knowledge.

Financial institutions

Financial services have been identified as a significant safeguarding environment for older people's finances (Fealy et al., Reference Fealy, Donnelly, Bergin, Treacy and Phelan2012; Canadian Foundation for Advancement of Investor Rights and the Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2017). Despite concerns around client confidentiality (Harries et al., Reference Harries, Davies, Gilhooly, Gilhooly and Kinnear2014), banking staff can play an important role in detecting and responding to financial abuse of older people (Chandaria, Reference Chandaria2011). This can be represented within a duty of care to a vulnerable client (Central Bank of Ireland, 2012; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Stanley, Penhale and Gilhooly2013; Banking and Payments Federation Ireland (BPFI), 2019). However, although financial institutions, such as banks, are key players in both preventing and intervening in financial abuse, their proactivity in this area has been cautious, while research exploring experiences, actions and potential for inter-sectoral collaboration is scant in the extant literature. Therefore, this study aims to understand the perceptions and experiences of bank managers and key informants in the financial abuse of older people within banks.

Research question

The research question is:

• What are the experiences of bank managers and key informants (National Safeguarding Committee (NSC)) of financial abuse of vulnerable adults in banking institutions?

The secondary research questions are:

• How are vulnerable adults (as customers) defined in banking systems?

• What types of financial abuse of vulnerable adults have been experienced?

• What responses have been taken in responding to financial abuse of vulnerable adults?

While the broader study focused on adults at risk (18 years and older), this paper presents findings related to older people (i.e. aged 65 years and older).

Methods

Design

A mixed-methods approach was used in data collection. Qualitative data were collected from 25 participants related to financial abuse of older people in banking institutions. The second method of data collection was an online survey with 898 front-line banking staff. This paper reports on the qualitative data, collected through 25 face-to-face, semi-structured interviews. Study approval was received from the Human Research Ethics Committee – Life Sciences, University College Dublin.

Setting

The setting for data collection was the Republic of Ireland. Five banks agreed to participate in the study. To provide an insider perspective of financial abuse of older people rellated to banking intuitions, the sample comprised 20 bank managers. A further five participants were recruited from the NSC, which was a multi-disciplinary, multi-sector group, established to promote a collaborative approach to safeguarding vulnerable adults (NSC, 2016). The five participants provided an outsider perspective of financial abuse within banking systems.

Participants

A purposive sample of 20 bank managers were recruited: 15 were male and five were female. Information was circulated to the banks through the BPFI, an umbrella organisation for financial institutions. For bank managers, the inclusion criteria were:

• To have experience of five or more years in the bank system.

• To be currently in a bank management-level position.

Thirty-eight expressions of interest were received and a final number of 20 were interviewed, stratified for geographic region (urban/rural) and individual bank participation proportionate to bank customer volume. Fourteen described their location as urban, while six described their location as rural. One participant was based in an urban area but had a specific vulnerable customer remit which spanned both urban and rural locations. Urban banks tended to have large customer bases while rural banks had proportionately smaller customer bases but spanned a wider geographical coverage.

For the NSC, the Chair agreed to forward a letter to invite five members of the larger committee (N = 32). The inclusion criterion was to have interaction with older people who have experienced actual/suspected financial abuse relating to third parties’ perpetration which involved an aspect of banking service provision. Three participants were male while two were female; all offered their perspectives based on the sector they represented.

Data collection

Qualitative data were collected over four months from August 2017 to November 2017. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with topic guides. Topic guides differed for the bank managers and the NSC members, and provided a flexible method to guide the interview, enabling the use of open-ended questions and follow-up probing to develop the perspectives of participants (DeJonckheere and Vaughn, Reference DeJonckheere and Vaughn2019). Interviews were recorded and lasted between 45 and 90 minutes.

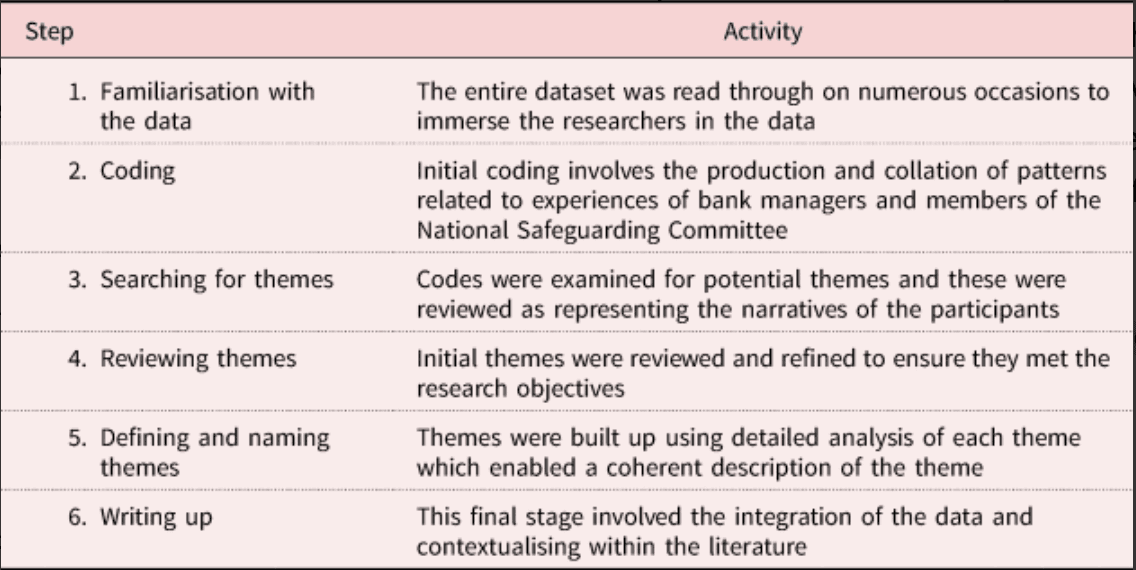

Data analysis

Transcribed interviews were imported into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne). Thematic analysis was undertaken by two researchers using Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) method. The six-phase process involved the steps identified in Table 1. Ongoing discussions between the researchers served to ensure consistency of findings with the finalisation of data representing mutually exclusive themes.

Table 1. Thematic analysis process (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006)

Findings

Four discrete themes emerged from the interviews. These were defining a vulnerable adult, cases of financial abuse of vulnerable adults, case responses to financial abuse of vulnerable adults and contextual issues.

Defining a vulnerable adult

Being able to suspect financial abuse of a vulnerable adult pivots on having an understanding of what constitutes the risk that renders older people vulnerable. Vulnerability was seen as a complex, multi-faceted phenomenon. It could be understood as an older person who has decision-making capacity but might need support (because of physical disability) or it could be related to decision-making capacity on financial matters:A ‘vulnerable adult’ would be somebody who has the capacity to make a decision, but may need assistance in doing so. But then you also have, you would have adults that would be operating accounts that have got to a stage in their life where they don't have the capacity to make decisions and they need more assistance in relation to acting on a day-to-day basis or their financial circumstances. (Bank manager (BM) 1)Alternatively, vulnerability could be temporary, e.g. following a bereavement, where decision-making ability might be impacted by grief and the shock of loss:[What] shuts down is their ears or their memory and what have you so we concentrate more on the initial meeting around making them feel welcome. (BM 20)Yet, there was a recognition that vulnerable customers were a heterogeneous group and it would be erroneous to use stereotypical assumptions of age. One of the NSC members observed that vulnerability was:…a very subjective term, one person's vulnerability is another person's bad day or another person just a condition that they have to deal with. It's not a concrete definition and it possibly might contribute to stereotyping of people once they become a certain age or once they reach a certain age or if they lose certain faculties that they have. (NSC 5)While participants offered various interpretations of vulnerability, as a concept it has been considered vague and broad (Schroeder and Gefenas, Reference Schroeder and Gefenas2009). Simply equating vulnerability to old age is problematic as this points to an ageist perspective based on assumptions of homogeneous ageing processes and focuses on the older person failing to have or attain autonomous agency (Bozzaro et al., Reference Bozzaro, Boldt and Schweda2018). Despite this, research has demonstrated that physiological changes of old age can impact vulnerability. For instance, advanced years have been shown to affect the interior insula of the ageing brain, making the recognition of deception more challenging (Castle et al., Reference Castle, Eisenberger, Seeman, Moons, Boggero, Grinblatt and Taylor2012).

Ethical arguments point to understandings of vulnerability which have been enmeshed in being unable to protect one's own interests while balancing protection and autonomy are key considerations (Bracken-Roche et al., Reference Bracken-Roche, Bell, Macdonald and Racine2017). Although the term ‘vulnerable’ has been contested in recent years, and the concept of ‘at risk’ considered more representative and non-stereotypical (Canadian Foundation for Advancement of Investor Rights and Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2017; Dalley et al., Reference Dalley, Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Levi and Harries2017; Mazars et al., Reference Mazars, Phelan, O'Donnell and Stokes2020), the term vulnerable continues to be used in various Irish policies (Central Bank of Ireland, 2012; HSE, 2014; NSC, 2016). In this study, older person risk of financial abuse was conceptualised in a number of ways, which could be temporal (bereavement), encompass cognitive challenges (related to the ability to understand actions) and/or physical challenges (needing another person to complete banking transactions).

While the use of the word ‘vulnerable’ in elder abuse has received some opposition, its application is used in the Banking Consumer Code of Ireland:‘A vulnerable consumer’ means a natural person who: a) has the capacity to make his or her own decisions but who, because of individual circumstances, may require assistance to do so (for example, hearing impaired or visually impaired persons); and/or b) has limited capacity to make his or her own decisions and who requires assistance to do so (for example, persons with intellectual disabilities or mental health difficulties). (Central Bank of Ireland, 2012: 77):Consumer vulnerability has been recognised as an interplay of person, individual traits and the context within which the older person lives (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Gentry and Rittenburg2005; Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Bene and Hideguti2017). Reflecting this definition, participants proposed that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors could render a person at risk of financial abuse. This concurs with other research which links financial vulnerability to the victim's cognitive/emotional status, medical and functional factors, psychosocial factors and environmental/societal factors (Lacks and Han, Reference Lacks and Han2015).

There has been a growing recognition of banks’ responsibility to vulnerable customers. Irish banks have expanded their duty of care, particularly in recent years, with the introduction of decision-making capacity legislation (Government of Ireland, 2015) and the establishment of a Vulnerable Customer Forum by the BPFI, with individual banks creating supports such as specialist vulnerable customer units or customer care experts/phonelines to combat risks such as financial abuse.

Cases of people with financial abuse of vulnerable adults

All participants spoke of actual or suspected cases of financial abuse of older people. The manifestations were diverse but constituted sub-themes of abuse by strangers, abuse by family/friends or carers and cases where capacity was a concern. These accounts included opportunistic instances of financial abuse, card fraud, decision-making capacity concerns and cases where there was suspected undue pressure placed on the older person.

Abuse by strangers

In the context of abuse by strangers, it was noted that the mode of scams had evolved with the advent of increasingly complex technology:Historically, if we go back before it became kind of technology fraud, it was people doing jobs on people's houses and then telling them that it was costing them €5,000 … for cleaning the windows and things like that. (BM 17)A common narrative related to scam lotteries. Accounts of older people who were lured into believing in the scam's authenticity were described. Once lured in, there could be a long engagement where money was extracted through multiple, incremental ‘costs’ over significant periods of time. These costs could, on the surface, appear plausible, but were focused on putting a continuous drain on the older person's finances. Consequently, such costs may be individually small amounts but over the period would amount to significant outputs. The excerpt below reflects on an older man who recounted a history of multiple payments for imaginary costs such as certificates, taxes or registrations:The scary thing about this case is from 2012 to recently … he was sending money via [money transfer company] for different reasons, anti-money laundering certificates, to register the cheque, to register you know, the taxes. He was sending all different money. In 2014, he then said, ‘I am not paying money via [money transfer company] anymore because there are charges associated with that as well’. So he said, ‘I am going to do it via the bank’ so he asked for bank account details, which they gave him, it was Spanish bank account details. He then started using us from 2016 to 2017 when it was referred to me. (BM 9)Likewise, financial abuse through opportunism could occur via the phone where callers affiliated themselves with real companies, such as impersonating a bank representative or being staff in a very well-known technology company to ‘fix’ a local computer problem:…the ones [cases] that are coming to us that are the customers that I have seen they have often pretended that they are from the bank. So, they say they are from [bank] or the other common one is Microsoft. (BM 9)Cases could also involve undue pressure, for example, when rogue traders attempted to charge for bogus work. Moreover, any work undertaken could be of dubious quality:…we sat down with them, we sat him [older person] down, we left your man [rogue trader] sit down waiting in the banking hall, and he [older man] was saying, ‘I wouldn't be happy with the work they [rogue traders] did now and I really feel under pressure here now, I'm struggling here.’ (BM 6)In another case, one bank manager recounted that the older person was placed under undue pressure to have his account used as a money-laundering mechanism (mule account) for drug dealing – a form of financial abuse not previously noted in the literature:So I brought the customer into an office and sat down and he kind of started telling me a story that he, that his ‘granddaughter’ was going to [country] and he needed to give her the money, but he didn't think she should go and with that … it was only very early into the conversation, when a young girl in her early twenties came in and started screaming and shouting looking for her ‘granddad’. As it turned out it wasn't her granddad, it was a mule account. She came in screaming, shouting, looking for the money… (BM 3)

Abuse by family, friend or carer

As health declines, negotiating activities such as shopping could manifest in sharing the Personal Identification Number (PIN) of a bank card so a family member, friend or carer could undertake the required purchases. Yet, this could provide the mode of abuse perpetration, while taking small amounts to mask the theft:Yeah and [carer] was creaming off very small amounts because she had the number. She'd take the card out of the kitchen and go and withdraw money and then put it back again and, you know, it was very small amounts that were taken out so it was very easy to do. (NSC 4)Thus, while such arrangements appeared practical, they also opened up opportunities to financial abuse, while also breaching the bank's terms and conditions. With the introduction and expansion of online and card banking, it was observed that chequebook fraud had reduced, although some incidences were still recounted:…sometimes you would have seen maybe sons taking cheques from parents’ accounts and you know using them but not I suppose cheques are less and less prevalent now as well so I wouldn't see as much. (BM 8)Both card fraud and cheque fraud represented a naïve trust in the perpetrator. In many cases, bank managers identified that further action related to criminal prosecution would not be pursued by older people who were financially abused by family members:Actually, we had an instance of it here in the [place] last year where … like brought in like the person … they were completely shocked. Yes couldn't believe it was their relative so then like we asked you know we said ‘Look we can bring this further’ and they didn't. You know I've never had a family one [customer case of financial abuse] that wanted to go further. (BM 8)Equally, there was some concern regarding older parents’ potential naïvety in opening a joint account. A joint account with the intention of convenience could result in financial abuse:And unfortunately, generally when it's [joint account] husband and wife typically, or a married couple or maybe a partner it tends to be okay but you will find sometimes people might bring a distant relative in or depending on if there's an ageing customer they have some family member, maybe a nephew or a cousin, or a grandchild, possibly. I'm not saying again we've seen any evidence of that but there's always … potential. (BM 6)In addition, having kinship ties or other people simply supporting the older person could result in the misplaced perception that there was an entitlement to assets or finances. This could manifest in actions where money was removed from an older person's account without legal authority. A member of the NSC recounted how one relative they had engaged with detailed an unproblematic approach to simply removing their mother's money from her bank account to pay an outstanding care home bill, even though consent was absent:‘Don't worry I'll just to go Mammy's account ten times and take out €900 each time’ … [daughter] and I said ‘No you won't’ and I said ‘it has to be done properly’. (NSC 5)Such a sense of entitlement could be supported by solicitors. In one description detailing an experience of relatives’ accessing money in an account without proper permissions, the rationale was they were going to inherit it, in any event:Now I spoke to the solicitor because she … but we know her very well, and she said to me ‘The bottom line of this is, if the two relatives spend all the money now, they're just spending their inheritance, because they're the only people that are going to get it.’ (BM 8)Other domains of undue influence concerned threats to withhold visits from grandchildren while another account was an older man who was threatened to be reported (without cause) to the police for sexual molestation by a younger girl, unless he surrendered money to her.

Cases involving issues related to capacity

In detailing cases of financial abuse, participants observed that the capacity of older people to engage in their financial affairs was a frequent concern. Capacity related to two areas: capacity to physically go to the bank to conduct financial affairs and capacity related to decision-making on financial matters. With regards to decision-making capacity, there could be two positions. On suspecting that there were challenges, bank managers may contact a family member. In the case below, the bank noticed that large amounts of funds were being forwarded to a cats and dogs’ shelter, without an understanding of depleting the customer's own scarce funds:In terms of dementia, you know, I suppose all we do in that case is we find out if there is a member of the family that we can ring to flag that there is something … we are concerned about. (BM 17)However, it was noticed that even if legal arrangements were in place, e.g. via Power of Attorney, this could be abused:I've had at least certainly two cases where Power of Attorney has been abused and we cancel the Power of Attorney to the high court where a person transferred a person's sold land on behalf of a vulnerable adult [older person] and lodged those proceeds to an account generating false invoices for a home care … [He/she] managed to move funds, significant funds. (NSC 1)The wide and varied cases that were reported identify the multiple and complex manifestations of financial abuse. This study has demonstrated that a suspicion of financial abuse perpetrated towards older people is not uncommon among bank managers’ experiences; all participants had multiple examples of case suspicions. Similar to the literature on financial abuse of older people (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Cairns, Davies, Harries, Gilhooly and Notley2013; Harries et al., Reference Harries, Davies, Gilhooly, Gilhooly and Kinnear2014; Dalley et al., Reference Dalley, Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Levi and Harries2017), the case accounts reflected many types of financial abuse, both related to family members and opportunism (rogue traders, lottery scams). A systematic review and meta-analysis (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Henderson, Sheppard, Zhao, Pillemer and Lachs2017) identified that a minimum of one in 18 older people living the community are subject to scams every year. A more recent study (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Taylor, Kingston and Watts2021) has observed the ubiquitous nature of scams such as fake lotteries, fake charities and romance scams, all of which were in the cases identified by the participants. It was also identified that scams perpetrated on older people can lead to embarrassment, shame and lowered self-esteem, often compounded by a lack of empathy from others; this can impact reporting (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Taylor, Kingston and Watts2021).

Participants’ experiences identified common contextual issues within suspected abuse cases, which included entitlement, decision-making capacity, an altruistic confidence in family or strangers, and similar to other studies, naïve trust, poor financial decision-making and a lack of financial awareness (Nguyen at al., 2021). Although, many families do not engage in financial abuse, risk rises with a dependency, and what may appear convenient, such as sharing a PIN, can lead to financial abuse.

Issues related to undue influence and coercion were also described in this study as methods of accessing the older person's finances. Finances may be removed through power differentials, the older person's desire to keep contact or through unfair pressure to make financial decisions (Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Nerenbery, Navarri and Wilber2017), even when these actions went against the older person's better judgement (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Mosqueda, Windisch, Weissberger, Axelrod and Duke Han2021). Compounding this, a common perception by adult children is an entitlement to their parents’ assets, due to inheritance perceptions, kinship ties, or that the older person can simply afford to lose/give away the money or property (Tilse et al., Reference Tilse, Wilson, Setterlund and Rosenman2005a, Reference Tilse, Wilson, Setterlund and Rosenman2005b; Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Fairman, Rosen and Wilber2011; Phelan, Reference Phelan and Phelan2020).

While an Enduring Power of Attorney is a mechanism for a trusted person to manage financial affairs, it can lead to financial abuse when the attorney abuses the older person's trust and confidence (Purser, Reference Purser2021). There were accounts of older people who did not appear to have functional capacity to make financial transactions. Evidence demonstrates a link between diminished financial decision-making and abuse due to neurocognitive disorders as well as factors such as the incorporation of psychological and cognitive variables (Lichtenberg et al., Reference Lichtenberg, Gross and Ficker2020). Studies have also demonstrated that abstract thinking, such as managing finances, is commonly found to decline in early dementia leading to financial confusion (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Griffith, Belue, Harrell, Zamrini, Anderson, Bartolucci and Marson2008; Marson, Reference Marson2013; Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Byrne, Mitchell and Pachana2015). Yet, dementia may not be diagnosed for some time as the person may delay in seeking help (Perry-Young et al., Reference Perry-Young, Owen, Kelly and Owens2018). There is also an association of diminished financial capacity with depression and mood disorders (Vaitsa and Tsolaki, Reference Vaitsa and Tsolaki2021), loneliness and poor physical health (Wong and Waite, Reference Wong and Waite2017). Thus, in the early stages of such health decline, particular challenges may already exist in managing finances and compensatory mechanisms may involve third-party assistance. This points to the fundamental importance of holistic health reviews, including the application of financial capacity assessments and screening older people for loneliness, depression and mood disorders.

Responses to financial abuse

Responses to financial abuse were tailored to the situation and based on recognising red flag cues and taking action to get more information and consider appropriate intervention. Responses included using intuition, identifying the reality of scams, seeking advice, stalling transactions and sharing knowledge of suspected financial abuse.

Most bank managers spoke of lottery scams, such as the ‘Spanish lottery’. They observed that older people could be confident in their legitimacy and adamant in sending off money convinced of a real prospect of the big win. However, efforts to orientate the older person to reality included a careful review of communication, where often bogus letterheads were used as well as suspect certificates (blurred text or careless photocopying). Additionally, strategies included a conversation based on logic:And I said, ‘Did you enter the Spanish lottery?’ you know, after a conversation with him and honestly the hair stood on my head and he said, ‘At the time [name] I did not.’ (BM 9)Often, the complexity of individual cases involved seeking advice. This was in two ways: bank managers could seek advice from regional or head offices and may specifically seek their banks’ legal input into dubious or suspect transactions. The second form of advice was related to advising the customer him- or herself to seek or to involve a trusted person:One customer was getting some building work done and he was taking out lots and lots of money, so I brought him in and I told him I wanted to talk to him and he was a little bit confused so I asked him to bring in his sister with him to make sure that the building work was going on and they were happy. (BM 11)However, it was noticeable that few bank managers were aware of the HSE's safeguarding service in terms of referring a customer where there was suspected abuse. In addition, contacting the police in relation to suspected financial abuse was not a common action. Another strategy was to stall the person, particularly if a significant action was being undertaken, e.g. opening a joint account. Stalling allowed more time to reflect and the bank manager followed up that evening with a phone call, when the older person was alone:We may not open it [joint account] immediately because what we'd say then is, ‘Well we have to get our documentation, we have to get all the procedures’, so a phone call, ‘Are you still happy to go ahead with opening this account?’ (BM 11)A final aspect of responses to financial abuse was sharing concerns. For example, an account could be electronically ‘flagged’ to alert staff in any branch about concerns. In addition, internal communication could be circulated to alert other bank branches to dubious activities. There was also an increasing focus on training staff to recognise and respond to suspicions of financial abuse:But in fairness, with ourselves, you know there is a good bit of information and training on the side of the whole vulnerable side of it, which is good. (BM 19)All the bank managers were experienced in their roles and detailed a careful assessment of the individual situation where financial abuse was suspected and taking action was tailored to the case.

In a UK study of banking staff, it was observed that staff's assessment of financial abuse was less clear if the older person was able to manage his or her money (Harries et al., Reference Harries, Davies, Gilhooly, Gilhooly and Kinnear2014). However, using a bystander model, Gilhooley et al. (Reference Gilhooly, Dalley, Gilhooly, Sullivan, Harries, Levi, Kinnear and Davies2016) suggest banking staff navigate five steps in intervening, namely (a) noticing relevant cues to financial abuse, (b) construing the situation as financial abuse, (c) deciding the situation is a personal responsibility, (d) knowing how to deal with the situation, and (e) deciding to intervene. These steps were evident in the bank managers’ narratives, yet the strongest consideration of the participants was the issue of decision-making capacity which has been identified by Harries et al. (Reference Harries, Davies, Gilhooly, Gilhooly and Kinnear2014) as heightening staff's decisions to intervene.

Bank staff's actions to prevent and intervene in the financial abuse of older people requires knowledge and training in addressing the issue as well as inter-sector collaborations. Within the bank managers’ narratives, it was recognised that financial abuse training had been instigated in some banks, however, there was a need for continued training and education as well as further support for new front-line staff from senior colleagues. In the USA, financial institutions have recognised the importance of education and training, and developed bespoke programmes for staff since 1995, while in 2007, the Australian Ombudsman's provided 14 red flags to increase competency and assist banking staff's recognition of financial abuse (Peisah et al., Reference Peisah, Bhatia, Macnab and Brodaty2016). More recently, the American Association of Retired Pensioners (2021) and the American Bankers Association (2021) have hosted staff training programmes and the Australian Banking Association (2021) has made efforts to update training of banking staff to recognise financial abuse. Education and training for bank staff should incorporate global advancements in this area while presenting the context of local legislation and policy (Harries et al., Reference Harries, Davies, Gilhooly, Gilhooly and Kinnear2014). Given the circumstances of opportunistic scams, which can be perpetrated from other countries, there is also a need to develop more robust linkages with international banking colleagues.

Another useful training focus relates to staff understanding dementia and decision-making capacity (Safeguarding Ireland, 2020) as many bank managers detailed issues related to decision-making challenges related to their older customers. For example, Peisah et al. (Reference Peisah, Bhatia, Macnab and Brodaty2016) developed a training programme specifically tailored to the banking environment to (a) enhance awareness of issues related to dementia; (b) increase knowledge of financial capacity, decision-making and the nuances of financial abuse of people with capacity challenges; and (c) identify appropriate responses within banking systems. In addition, further expansion of bank staff's knowledge of capacity generally and the provisions within the Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act 2015 will be of particular importance.

Public awareness campaigns by banks are also needed to educate older people on the implications of various financial actions such as joint accounts and giving PINs to another person. Raising knowledge and awareness of financial abuse and older people also transcended the banking environment as it was noted that societal views such as ageism, entitlement, families as altruistic agents and practices such as coercive control need to be addressed through inter-sector collaboration. Yet, the bank managers’ narratives pointed to a traditional, siloed approach to financial abuse within banks in Ireland. While many states in the USA have recognised the potential of dubious transactions to exploit older people financially and have introduced banking staff as mandatory reporters as well as establishing Financial Abuse Specialist Teams, Ireland has not developed a comprehensive, integrated, multi-sector approach nor does it have specific safeguarding legislation. While this was recognised by the NSC, bank managers rarely spoke of working with or reporting to other sectors when there were suspicions of financial abuse. This may be due to the current perceptions of limitations of client confidentiality, particularly within the General Data Protection Regulations, with a resulting protectionist (from referral) stance due to fear of legal repercussions. However, even though financial abuse may have blurred parameters, due to issues of consent, family allegiances or confidentiality, financial abuse often constitutes a criminal act as well as potentially having an impact on the health and welfare of the older person. The advantages and disadvantages of having mandatory reporting for elder abuse was discussed in a recent Issues Paper (Law Reform Commission, 2019), however, Safeguarding Ireland (2020), supports comprehensive, robust and overarching standards and guidance rather than mandatory reporting due to an erroneous presumption that mandatory reporting would address the more serious forms of abuse, yet could result in an overwhelming of the safeguarding services with unwarranted referrals.

Contextual issues

The context of financial abuse provided two sub-themes, a geographical perspective (rural versus urban banking) and the changing face of banking transactions.

Geographical perspective

Within the sampling phase, the researchers engaged in recruiting a mix of urban and rural bank managers. The relationship in more rural areas was considered more intimate:Yeah, sure it's [really knowing the client] different in [city 1] or [city 2] or whatever where the volume would be a lot bigger. (BM 12)Bank managers also observed that there was also a higher experience in rural areas of genderised roles with older women looking after the house and the older husband managing finances:I'd often have the husband and wife would come in here and possibly rural elderly couple and one does all the talking, the other doesn't say one word and that's the way it is, it's just the way the family is run. (BM 5)

Changing face of banking institutions

Like other countries, Irish banks are undergoing a technological revolution with a move to online banking. However, it was recognised that the need for face-to-face banking persists:The one thing, I would say when dealing with anybody who's not comfortable with internet or phone banking or whatever[; c]reate the service that they want, don't ask them to buy into the service that you're offering[;] if older people were to design their banking service, they would say something that is in the town, don't close down our banks. (NSC 5)Equally, there had been closures of smaller rural banks and there could be a reluctance by older customers to manage online banking. This provided the potential of giving others access to assist in negotiating account management and could lead to breaching bank regulation:…[we would find that older people in particular are concerned about vulnerabilities and] how to use online banking and their natural apprehension and fear in some cases towards it but then secondly to that is they tend to probably give their access details to various different people in their circle that they'd trust, which obviously is against bank regulation. (BM 15)This theme was the least represented area in the extant literature. Rural bank managers spoke of having a closer relationship with their older customers. The age profile of rural bank customers has been noted to be greater than urban areas while volumes are higher in urban areas (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Grundi and Windle2020). From this study, it can be concluded that smaller customer numbers enable staff to have a greater potential to build relationships allowing a higher capacity to notice signs of suspected financial abuse.

Approximately 10 per cent of the rural population lives over 10 miles from a bank in the UK (Bennet, Reference Bennet2020). COVID-19 has presented higher risk for financial abuse in terms of the public health advice to older people to shield, enabling relatives to temporarily manage finances (KPMG, 2021). In Ireland, 11 per cent of people had made alternative financial arrangements during the initial pandemic lockdown, yet, two-thirds had not regained this control when public health measurements eased (Safeguarding Ireland, 2020). The COVID-19 challenge in managing finances is also compounded by a digital divide in older and younger age groups (Seifert, Reference Seifert2020) as online banking may not be accessible or desired in the older age cohort.

Rural bank closures can be linked to economic-based corporate decisions (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Grundi and Windle2020). Within the last few years, many of the large banks have made decisions to amalgamate with a disproportionate impact on the farming community (Irish Farmers Association, 2021). Within the literature, there is a paucity of publications which examine the impact of rural bank closures. Much of the narrative appears to be from community groups (e.g. Scottish Rural Action, 2018) objecting to closures, with commentaries from political parties on the negative impact. For example, the Social Democratic and Labour Party in Northern Ireland ‘believes that the provision of accessible banking is an integral part of social inclusion, with [closures having] a particular impact on the elderly’ (Scope, 2016). Likewise, Politics Home (2018) argues that banks have an obligation to undertake an impact assessment, noting that older people are one of the most affected population groups in closures. While the rise in online banking has given customers access to many everyday banking actions remotely, this uptake has not been age neutral. As COVID-19 has increased communications using digital technology, there remains a digital divide in age groups with older people having less access and poorer digital literacy (Anderson and Perrin, Reference Anderson and Perrin2017; Central Statistics Office, 2020). There is also a concern that online banking may not be sensitive enough to identify impaired decision-making in relation to finances, with screening of capacity to engage in electronic financial instrument use recommended (Greene, Reference Greenein press).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of the study. While the study focused on five of the major national banks in the Republic of Ireland, other financial institutions were not included (An Post, Credit Unions). Thus, transferability may be limited and staff from these institutions may have alternative experiences. Secondly, the participants were recruited at an individual bank level; interviews with regional legal and fraud sections of the banking institutions may have offered additional insights. Equally, the perspectives of older people, advocacy groups and regulatory authorities may provide alternative and/or additional perspectives. In addition, the wider study was on vulnerable adults. The data reported in this paper relate to the interview data discussing older customers. While the age of 65 years is commonly understood as entering the older person age group, and some participants qualified this by stating 65 years or by referring to retirement age, we acknowledge that some participants’ data may also relate to younger age cohorts.

Conclusion

Financial institutions, such as banks, are key environments for financial abuse of older people (Peisah et al., Reference Peisah, Bhatia, Macnab and Brodaty2016; Canadian Foundation for Advancement of Investor Rights and Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2017; BPFI, 2019). Yet, there are few studies which have focused on this setting to understand case presentations and responses. This study demonstrates that while banking staff have knowledge of factors related to risk of financial abuse and have experienced suspicions of financial exploitation, there is little evidence of inter-sectorial collaboration with health and social care or formal involvement with police or legal systems. These challenges are evident in international evidence as financial abuse of older people remains under-prosecuted. Consequently, cases can be handled locally within the sector and may often encompass the intuition of bank managers in stalling transactions or trying to follow up to elicit the older person's transaction understandings. Although more recent years have highlighted a need of a duty of care to vulnerable adults, including older people, more work is required in education relating to the financial abuse of older people. In addition, with the rise of scams which can emanate from international sources, a focused protection within banking systems globally would enable prevention and early interventions.

As financial abuse is a multi-dimensional issue, it demands a multi-focused, collaborative response to achieve the safeguarding older people from economic crimes, such as those perpetrated within banking systems. As crimes, they need to be reported to access legal redress.

The health and social care system should increase screening for financial capacity and work with banks and other sectors to promote actions which reduce risk, both for older people with and without decision-making capacity, and sectors need to intervene early to limit loss.

Within an information technology age, older people need to be supported in digital literacy, if desired, but to also have access to financial institutions for transactions through alternative modes that they deem acceptable. Efforts should address issues of concern such as data protection, sharing information and ongoing inter-sector collaboration in suspected cases. Finally, a cultural shift is needed to address issues of family exploitation of an older person's assets, such as the use of undue pressure, coercion or the perception that there is an entitlement to such assets. Many of these findings have application internationally as the domain of financial institutions recognise obligations of financial safeguarding and the imperative of collaborative activities in both prevention and intervention.