Abstract

Background: Fentanyl and related compounds have recently saturated the illicit drug supply in the United States, leading to unprecedented rates of fatal overdose. Individuals who are incarcerated are particularly vulnerable, as the burden of opioid use disorder is disproportionately higher in this population, and tolerance generally decreases during incarceration. Methods: We conduct a systematic search for publications about fentanyl overdoses during incarceration in PubMed and PsycINFO, as well as lay press articles in Google, from January 1, 2013 through March 30th, 2021. Results: Not a single fentanyl overdose was identified in the medical literature, but 90 overdose events, comprising of 76 fatal and 103 nonfatal fentanyl overdoses, were identified in the lay press. Among the 179 overdoses, 138 occurred in jails and 41 occurred in prisons, across the country. Conclusions: Fentanyl-related overdoses are occurring in correctional facilities with unknown but likely increasing frequency. In addition to the need for improved detection and reporting, immediate efforts to 1) increase understanding of the risks of fentanyl and how to prevent and treat overdose among correctional staff and residents, 2) ensure widespread prompt availability of naloxone and 3) expand the availability of medications to treat opioid use disorder for people who are incarcerated will save lives.

Introduction

Opioid use and incarceration are interrelated problems in the United States. Even prior to the current opioid-driven overdose epidemic, up to one-third of people who used heroin were incarcerated annually (Boutwell, Nijhawan, Zaller, & Rich, 2007). Opioid use disorder (OUD) is more severe and advanced in justice-involved populations than in the general population (Winkelman, Chang, & Binswanger, 2018). While incarcerated, individuals often undergo a period of reduced opioid use that may lead to a diminished physiological tolerance to opioids (Binswanger et al., 2007). Reduced tolerance has been identified as a significant contributor to risk for drug overdose following release from incarceration, and it is estimated that individuals released from incarceration have nearly 13 times the risk of death as the general population, with overdose as the leading cause (Binswanger et al., 2016; Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2018; Green et al., 2018).

Fentanyl and related compounds have recently emerged as the primary drivers of the opioid overdose epidemic in the United States, having saturated much of the illicit drugs (Increases in Fentanyl Drug Confiscations and Fentanyl-Related Overdose Fatalities, 2018; O’Donnell, Halpin, Mattson, Goldberger, & Gladden, 2017; Ostling et al., 2018; Reported Law Enforcement Encounters Testing Positive for Fentanyl Increase Across US | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center, 2019; U.S. Drug Overdose Deaths Continue to Rise; Increase Fueled by Synthetic Opioids, 2019). As evidenced by toxicology reports and personal accounts from people who use illicit substances, illicit fentanyl is often mixed with heroin—although it has also recently been detected in cocaine and counterfeit opioid and benzodiazepine pills (Carroll, Marshall, Rich, & Green, 2017; Ciccarone, Ondocsin, & Mars, 2017; Korte, 2018; Suzuki & El-Haddad, 2017). Due to its lipophilic properties, fentanyl rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier and binds to opioid receptors (Suzuki & El-Haddad, 2017). Estimated to be between 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin and 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, fentanyl poses a much higher risk of overdose, even to those exposed to very small quantities (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Suzuki & El-Haddad, 2017).

In response to the worsening overdose crisis, policymakers and public health and medical institutions have launched initiatives to increase awareness of the risk and ubiquity of illicitly manufactured fentanyl in the community (U.S. Drug Overdose Deaths Continue to Rise; Increase Fueled by Synthetic Opioids, 2019). These efforts have primarily focused on promoting rigorously tested harm reduction measures, including education, naloxone distribution and access to low-barrier medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids, 2019). Naloxone is a fast-acting opioid antagonist that blocks the effects of opioids and can thus reverse opioid overdose. While the number of MOUD programs increase, and access to naloxone continues to expand in the United States to include first responders, lay people, and individuals who are at risk for overdose in the community, to date these efforts have been limited in correctional facilities (Horton et al., 2017; Kim, Irwin, & Khoshnood, 2009; Wenger et al., 2019).

Correctional systems utilize intense surveillance, sanction and control to prevent illicit substances from entering into facilities (Kolind & Duke, 2016). Despite these efforts, nearly all correctional facilities have ongoing problems with contraband, ranging from cell phones to illicit substances (Kolind & Duke, 2016). Illicit fentanyl is inexpensive, widely available, and easy to smuggle into facilities to due to its high potency and need for only very small amounts (Increases in Fentanyl Drug Confiscations and Fentanyl-Related Overdose Fatalities, 2018; O’Donnell et al., 2017; Ostling et al., 2018; Reported Law Enforcement Encounters Testing Positive for Fentanyl Increase Across US | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center, 2019;U.S. Drug Overdose Deaths Continue to Rise; Increase Fueled by Synthetic Opioids, 2019). People who are incarcerated are at an increased risk of overdose when exposed to fentanyl, due to its high potency and the lower tolerance levels resulting from decreased opioid use while incarcerated.

The present study

There are many causes of mortality in incarcerated populations including fatal drug overdose risk immediately following release, natural deaths, and intentional deaths during incarceration, including suicide on-site (Arfken, Suchanek, & Greenwald, 2017; Fazel & Benning, 2006; Kim et al., 2007; Larney, Topp, Indig, O’Driscoll, & Greenberg, 2012; Larney et al., 2014; Larney & Farrell, 2017; Mumola, n.d.; Salive, Smith, & Brewer, 1990). However, few studies have explored fentanyl-related overdose events in jails and prisons (Larney et al., 2014). Given the current fentanyl-driven overdose epidemic in the community and the presence of contraband drugs in correctional facilities, it is likely that there are fentanyl-related overdose deaths among individuals who are incarcerated. To better understand this, we conducted a comprehensive review of published reports of fentanyl-related overdose in correctional facilities, including jails and prisons. We aim to use our findings to gain a better understanding of the prevalence of fentanyl overdoses in prisons and jails in the United States to ultimately to reduce those overdoses and deaths.

Methods

In this comprehensive review, we examined fentanyl-related overdose events during incarceration in a jail or prison. We defined a fentanyl-related overdose event as the occurrence of at least one fentanyl-related overdose on a given day at a correctional facility. Thus, one overdose event may involve multiple overdose victims. Fentanyl-related overdoses that occurred at the same correctional facility but on separate days were not defined as one overdose event; rather overdoses on each individual day comprised unique events. We defined a fentanyl-related overdose as a fatal or non-fatal overdose that was either confirmed or suspected to involve fentanyl, as stated by the source.

We systematically reviewed the medical literature for reports of fentanyl-related overdose events during incarceration from January 1, 2013 to March 30, 2021. PubMed and PsycINFO were used to identify reports in the medical literature. We reviewed articles published using the search terms: (“fentanyl overdose”) AND (prison OR jail).

Due to the fact that we found no cases in the peer-review literature, we expanded our search to include the lay press. Google search engine and Google alerts were used to identify cases of overdose in the media and lay press from January 1, 2013 to March 30, 2021. We used the same search terms, “fentanyl overdose in prison” and “fentanyl overdose in jail,” in the Google search engine. Our results yielded local and national news articles, blogs, and press releases. All results were manually reviewed and examined until we reached a full page of search results that contained no articles relevant to the review. For each reported fentanyl overdose event identified, an additional Google search was initiated using details of the event as search terms, such as the name of the correctional facility or the overdose victim. All relevant articles and details of the overdose events were cataloged and collated.

Results

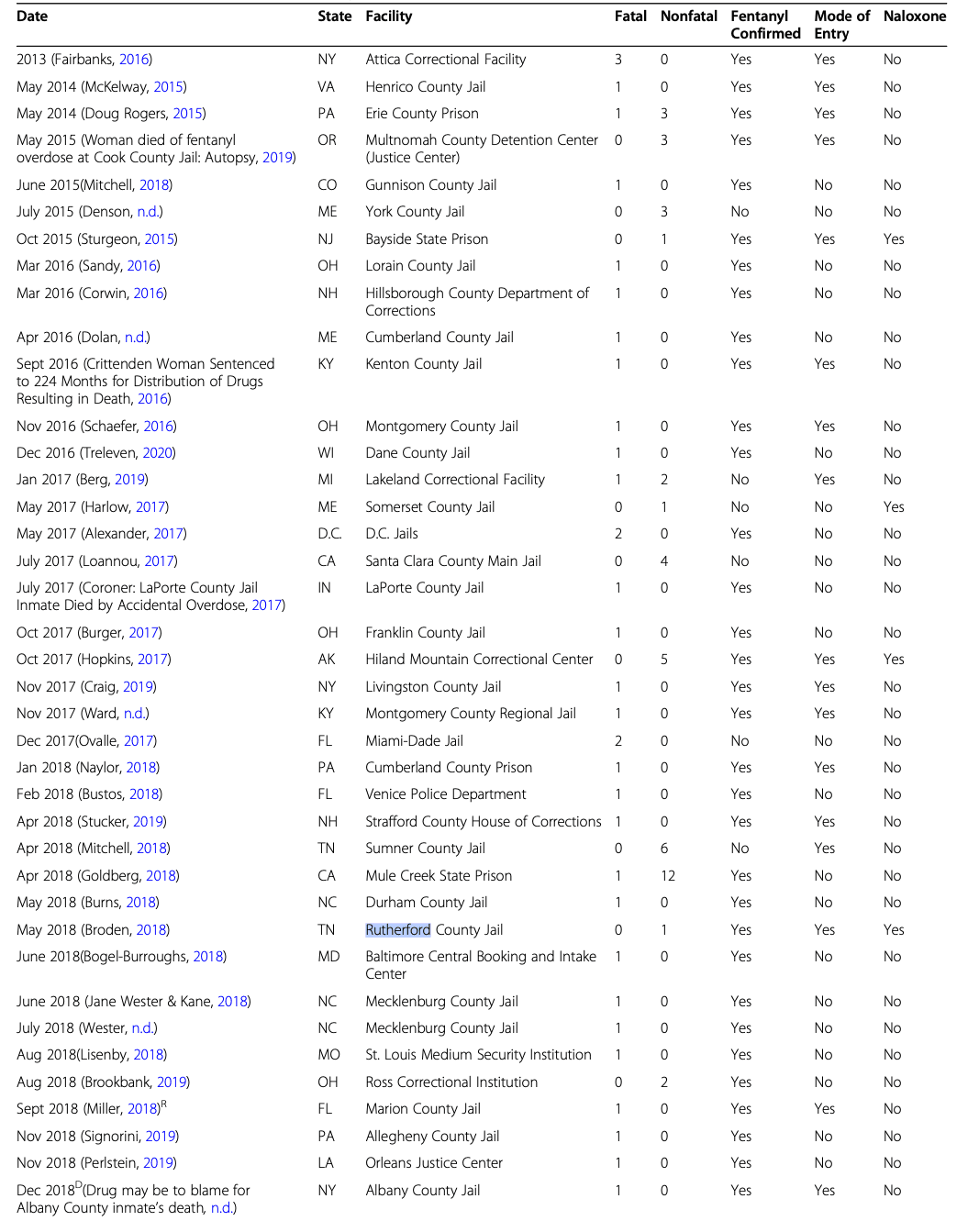

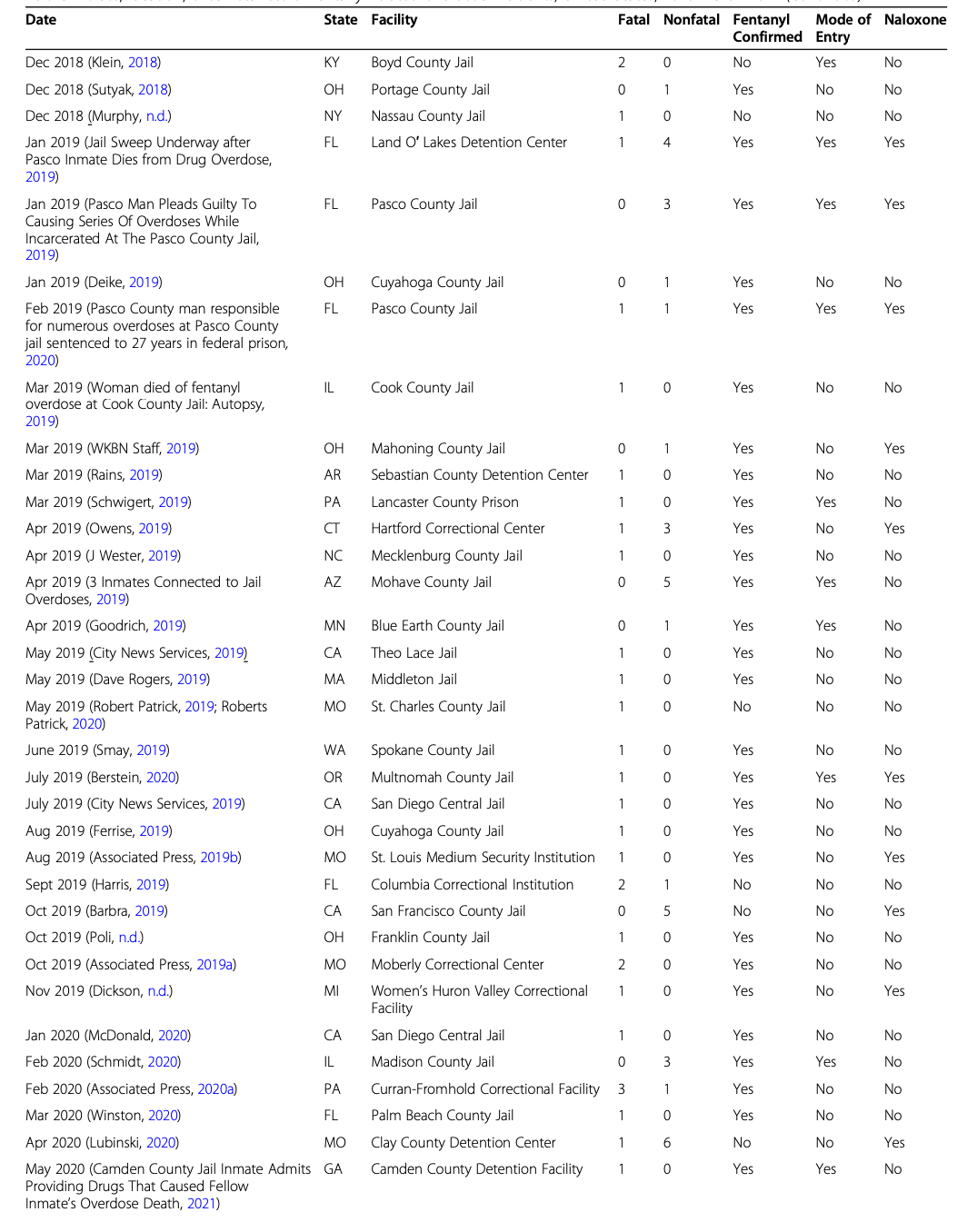

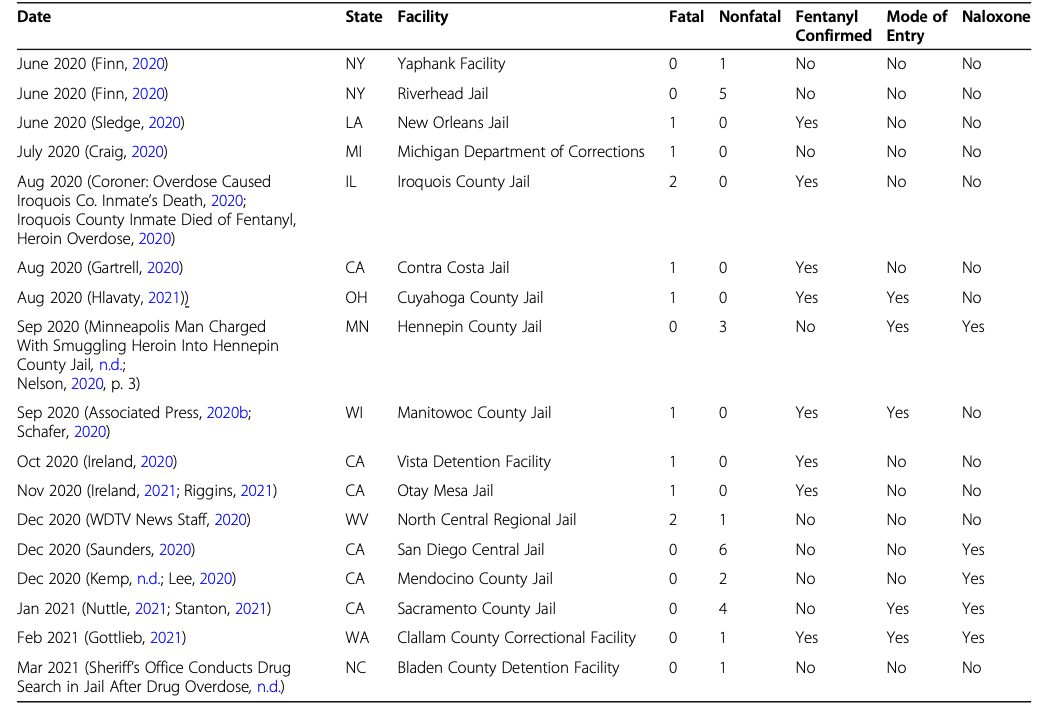

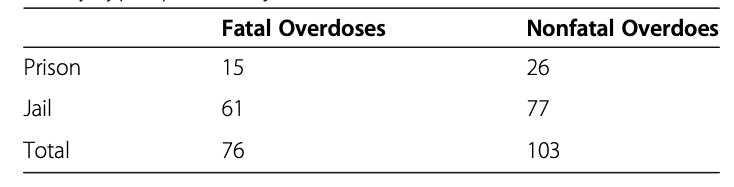

Not a single instance of fentanyl-related overdose reports or scientific articles among incarcerated individuals was identified through PubMed or PsycINFO. Our media analysis and search of articles in the lay press returned 113 relevant reports. After duplicate reports were combined, our results identified a total of 90 reported events comprising 179 fentanyl-related overdoses during the study period. Of these 179 fentanyl-related overdoses, 76 were fatal and 103 were nonfatal. One victim overdosed twice on different days (Hopkins, 2017). All United States regions were represented; specifically, reported overdose events occurred across 32 states and the District of Columbia (DC). California, Florida, Pennsylvania and Ohio were overrepresented with a total of 40, 18, 11, and 10 overdoses, respectively. Of note, 13 of the 40 overdoses in California resulted from a single events at the Mule Creek State Prison in April 2018 (Goldberg, 2018). Based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban classification scheme (USDA ERS - Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, n.d.), 72 overdose events occurred in metropolitan counties, 17 events occurred in nonmetropolitan countries with urban populations, and 1 event occurred in Washington, DC. Characteristics of the known and suspected fentanyl overdose cases among incarcerated individuals are presented in Table 1.

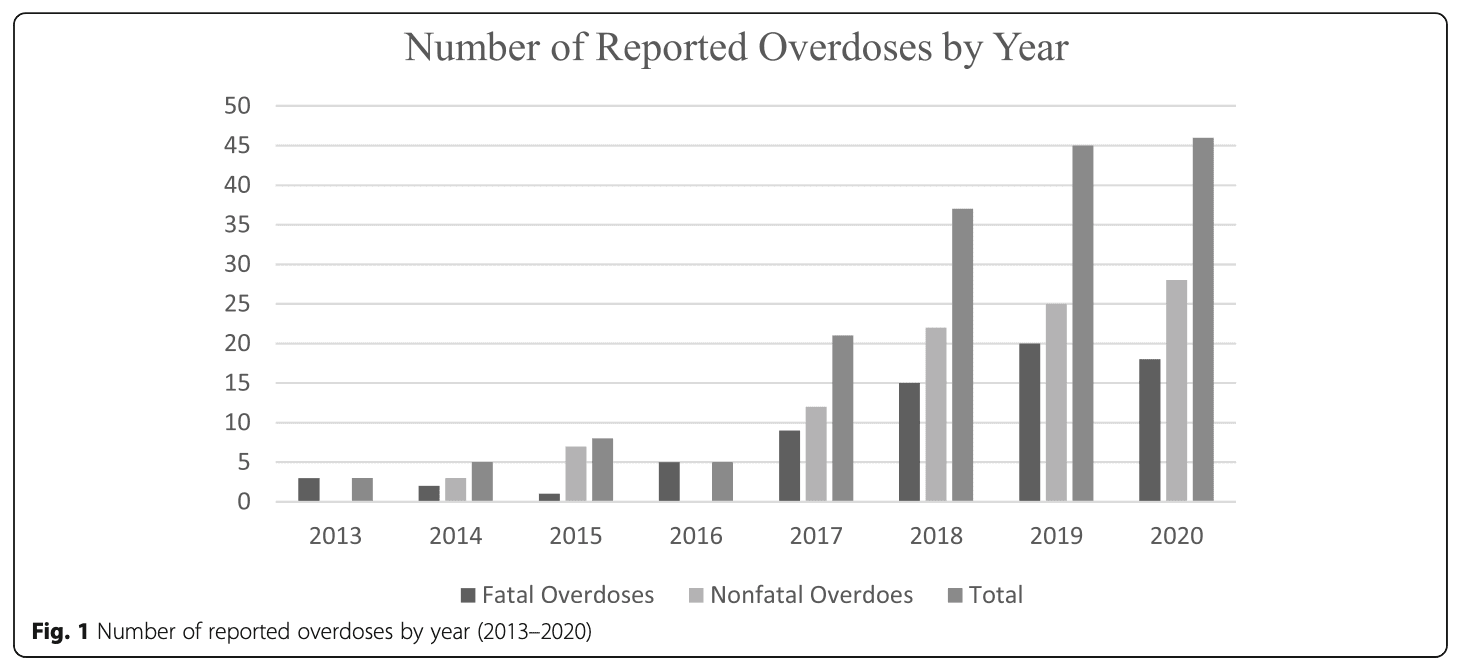

Table 2 presents the breakdown of fatal and non-fatal overdoses in prisons and jails, and Fig. 1 presents overdoses in correctional settings over time.

Confirmation of fentanyl

In 77% (n = 70) of included events, the involvement of fentanyl or its analogs was reported by the source. However, only a few overdose events (n = 12) were reported to include a systematic toxicology screening upon overdose. Most articles did not specify whether exposure to fentanyl was intentional or unintentional. During an overdose event in Covington, Kentucky on September 4, 2016, a young woman at the Kenton County Jail unintentionally consumed fentanyl and died of a fatal overdose (Crittenden Woman Sentenced to 224 Months for Distribution of Drugs Resulting in Death, 2016). Toxicology reports revealed a mixture of fentanyl and morphine in her body at the time of death; however, both her mother—who delivered the substance through two individuals who were incarcerated at the jail—and the individual her mother purchased the substance from believed it to be heroin (Crittenden Woman Sentenced to 224 Months for Distribution of Drugs Resulting in Death, 2016).

Fentanyl entrance

In outlining the circumstances around the fentanyl-related overdose events, 33 (37%) reports also described how fentanyl entered the correctional facility. Purported modes of entry included being smuggled in by a family member, a food service employee, a visitor during an open house, and an individual who was incarcerated and hid a bag of fentanyl inside her body. Many of the reports in the lay press emphasized the tight surveillance and security measures within correctional settings.

Response to overdose

Naloxone was administered to overdose victims in 20 (22%) events, one of which occurred in 2015 and the remainder of which occurred between 2017 and 2021. While naloxone was administered either by correctional or medical staff, individuals who were incarcerated played a critical role in response to overdoses in a couple of instances, such as when they notified correctional staff at the Lorain County Jail in Elyria, Ohio about an individual who was incarcerated who was overdosing (Sandy, 2016). In another instance from May 2014, individuals who were incarcerated at the Henrico County Jail in Henrico, Virginia applied ice on parts of the victim’s body in attempts to revive him after he overdosed, which is an ineffective method to reverse opioid overdose (McKelway, 2015). The overdose accounts included in this review demonstrate how the onset of fentanyl-related overdose symptoms is rapid. In an article describing a fatal overdose at the Baltimore Central Booking and Intake Center in June 2018, a victim’s health is described as having deteriorated rapidly after ingesting what was later confirmed to be a mixture of morphine and fentanyl. Less than an hour prior to overdosing, he was described as “cool, calm, relaxed” (Bogel-Burroughs, 2018). In another fatal overdose case, an individual who was incarcerated died on June 28, 2015 while in police custody at the Gunnison County Jail in Gunnison, Colorado. A check performed at 9:01 am did not raise concerns about his health. However, he was found unconscious 3 minutes later (Michell, 2016).

Discussion

This is the first paper to summarize fentanyl-related overdose events that occurred during incarceration. No reports were identified in the medical literature. However, we identified 90 overdose events totaling 179 overdoses in the lay press and these reports are rapidly increasing. The large discrepancies in reporting between the lay press and the medical literature suggests under-reporting of overdose events in prisons and jails, and a lack of attention given to the opioid crisis in correctional settings more generally. The number of fentanyl overdoses is likely much higher, as in an article published in the Orange County Register, a sheriff reported that 129 doses of naloxone had been administered to 70 individuals in 2019 (Saavedra, 2020), and yet, our media search revealed only a single reported overdose event in Orange County that year (OC Inmate’s Death Caused By Fentanyl Overdose, Officials Say, 2020). This suggests a vast under reporting of overdoses, and likely fentanyl overdoses in prisons and jails. We suspect that correctional administrators endure tremendous pressure to minimize the prevalence of substances and contraband inside, in an effort to maintain the perception that jails are safe and rehabilitative. For example, our team is anecdotally aware of six events of fentanyl related overdoses and deaths, that occurred in correctional facilities in two different states where the attending clinicians were told by their superiors not to report these cases in the medical literature.

As fentanyl contamination of the drug supply continues in the community, we expect its presence in correctional facilities to likewise rise in parallel. However, the scope of the problem is unclear because fentanyl overdoses in correctional facilities are not being systematically tracked. Unfortunately, as demonstrated by the few reports of systematic toxicology screening in our study, there currently is no standard of care for evaluating deaths among people who were incarcerated; ideally, an autopsy and complete toxicologic screening should be completed for all deaths occurring in correctional facilities. Enforcing a standard of care for all deaths and a system to systematically track deaths in correctional settings is essential to fully understanding the scope of the crisis.

However, further data is not necessary to begin addressing overdoses and deaths in corrections. Three evidence-based interventions can, and must, be implemented 1) educate correctional staff and individuals who are incarcerated about the risks of fentanyl, 2) ensure widespread, readily available naloxone accompanied with training on how to properly administer it, and 3) expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder in prisons and jails.

Our study found that naloxone was reported to be administered in only 22% of included overdose events. Both correctional staff and individuals who are incarcerated should be educated on the growing prominence of fentanyl, its effects, signs of an opioid overdose, and the use of naloxone. As a harm reduction measure, naloxone trainings should be widely available to all staff and individuals who are incarcerated. Studies of naloxone training in the correctional setting underscore the potential for individuals who are incarcerated to participate in trainings and correctly administer intranasal naloxone while incarcerated (Green, Ray, Bowman, McKenzie, & Rich, 2014; Kobayashi et al., 2017; Parmar, Strang, Choo, Meade, & Bird, 2017; Petterson & Madah-Amiri, 2017). At a minimum, naloxone should be present in all correctional units, and units should be staffed with correctional officers who are trained in naloxone administration. As of November 2018, RIDOC implemented the first statewide naloxone training for correctional officers, which included trainings to recognize overdose symptoms and correctly administer naloxone. Naloxone is now offered to RIDOC officers who completed the training and is readily available in all Rhode Island prisons (personal communication Jennifer Clarke, MD, MPH).

In addition to naloxone distribution, MOUD remain the gold-standard of treatment for OUD and an effective harm-reduction intervention to prevent overdose (Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids, 2019). The availability of and attitudes toward MOUD in correctional facilities are rapidly changing given the magnitude of the epidemic and the demonstrated decrease in overdose deaths among individuals recently released from incarceration. In a randomized clinical trial conducted by Kinlock and Gordon et al. in Baltimore, Maryland, participants who were incarcerated and assigned to receive both counseling and methadone were less likely to test positive for opioids at one-, three-, six-, and twelve-month follow-ups in the community compared to those who received only counseling (Kinlock et al., 2007; Kinlock, Gordon, Schwartz, Fitzgerald, & O’Grady, 2009; Kinlock, Gordon, Schwartz, & O’Grady, 2008). Our team has also demonstrated that individuals who are maintained on methadone while incarcerated are more likely to return to their methadone clinic after they are released than those who undergo forced withdrawal while incarcerated (Rich et al., 2015). Thus, not only does providing access to MOUD in corrections increase individual’s chance of recovery upon reentry, it also reduces risk of overdose during and after incarceration. Despite the robust literature demonstrating its efficacy, the use of MOUD in correctional facilities is still met with resistance. According to the Jail and Prison Opioid Project (JPOP), only 356 correctional facilities out of the nearly 5000 facilities in the United States offer any form of MOUD to individual who are incarcerated (Prison Opioid Project – Medication for Opioid Use Disorder and the Criminal Justice System, n.d.).The compounded problem of extremely concentrated, widely available and affordable fentanyl, and the lowered tolerance of individuals during incarceration, necessitates evidence-based interventions. Generally, there has been a lack of response among correctional facilities to address the growing opioid crisis; our study found that among the facilities that have attempted to respond to the overdose crisis, they have predominantly done so through increasing security and surveillance. However, a recent study found that increased surveillance and punishment among people using opioids was correlated to less likelihood to seek treatment and begin recovery (Mazhnaya et al., 2016). Harm-reduction interventions in the community have effectively reduced risk of overdose; however, there has been little focus on promoting these in criminal justice settings as well.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. To our knowledge, no scientific papers about fentanyl overdose during incarceration have been published, and cases reported in the lay press likely represent only a fraction of all overdose events. Moreover, due to the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, media coverage on correctional facilities has likely shifted towards COVID-19 outbreaks in facilities and away from fentanyl-related overdoses. Reluctance to release data on overdose within corrections likely also results in the underreporting of fentanyl-related overdoses. More systematic data collection, reporting, and surveillance of unintentional drug-induced deaths is needed to understand the magnitude of fatal and nonfatal fentanyl-related overdoses in the incarcerated population.

Conclusions

Fentanyl-related overdoses in correctional facilities are likely spill-over from the opioid epidemic in the community. Fear and misinformation around fentanyl exposure have contributed to the stigmatization of OUD and resistance towards effective harm reduction measures and treatment. Illicit drug use in correctional facilities occurs regularly. In the face of this evolving fentanyl-driven opioid epidemic, correctional staff, individuals who are incarcerated, and the public must be equipped with the knowledge and tools necessary to reduce and prevent fatal and nonfatal overdose events. Naloxone and MOUD, specifically, are beneficial after release and should also be safe and effective in jails and prisons. Moreover, systematic data collection, including toxicology screens, and increased reporting of fatalities in corrections are urgently needed to monitor and curb the opioid overdose epidemic.