Abstract

Despite clear aversion to such labels, one of the most impactful criminological theories is rooted in cognitive science. Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory has been repeatedly tested, replicated relatively well, and has since reached beyond its original scope to explain other important outcomes like victimization. However, the work never viewed itself as part of a larger scientific landscape and resisted the incursion of neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary theory from the start. This missed opportunity contributes to some of the theory’s shortcomings. We begin by considering relevant literatures that were originally excluded and then conduct a new analysis examining the cognitive underpinnings of victimization in a high-risk sample of adolescents. We used the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (n=3,444; 48% female; 49% Black, 25% Hispanic) which contained sound measures of self-control and intelligence, as well as four types of adolescent victimization. Self-control was robustly associated with all forms of victimization, whereas intelligence had generally no detectable effect. We discuss how these findings fit into a broader understanding about self-control and victimization.

Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) proposed theory about the causes of crime continues to guide criminological thinking well over three decades after publication (Pratt & Cullen, 2000). The work remains viable in large part because of its intellectual reach, which is constrained neither by its original focus or its discipline of origin (Tanksley et al., 2020). Consider, for instance, victimization, which has been studied across academic specialties for decades (Beckley et al., 2018; Cohen & Felson, 1979; Cohen et al., 1981; Duntley & Shackelford, 2012; Gottfredson, 1981; Schreck, 1999; Singer, 1987; Wolfgang, 1958). Understood in the correct manner, Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) work can help to make better sense of prior psychological, cognitive, and evolutionary insights about victimization (Duntley & Shackelford, 2012; Schreck, 1999). Because criminology as a whole has a history of intellectual isolationism, though, the conciliatory potential of the theory can be easy to miss (Boutwell et al., 2022).

Years ago, DeLisi et al. (2011, p. 365) correctly observed that: “Although Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory is a sociological one, its central construct is congruent to executive functioning.” Executive functioning relies on various neurological structures, which themselves were shaped and molded across the evolutionary history of our species (Maestripieri & Boutwell, 2022). Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) had no interest in situating theory in the broader contexts of either cognitive science or evolutionary biology (DeLisi et al., 2011). Filling in the gaps requires that we first review the relevant concepts that were absent in the original presentation of the theory. Readers familiar with these literatures will likely find some of what follows to be remedial. The audience we hope to reach is one less acquainted with work in the biological sciences. By adding a baseline awareness of concepts, though, the fit between puzzle pieces becomes more readily observed (DeLisi et al., 2011). From there, we offer a new empirical test applying these insights to victimization using a national sample of disadvantaged and low socio-economic respondents.

Brief Primers on Evolution, Executive Function, and Self-Control

Evolution by natural selection involves the non-random selection of genetic variants that improve the fitness of the carrier (Buss, 2009; Dawkins, 1976; Penke & Jokela, 2016; Penke et al., 2007; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990). Selection gives rise to complex design features, however, complexity alone does not signify that a trait is adaptive, as complex features can emerge as by-products of selection forces aimed elsewhere (Penke et al., 2007; Pinker 1997; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990). Another concept to mention is genetic drift, a chance process which impacts the distribution of neutral genetic mutations (see Keller, 2007; Penke et al., 2007). Despite a basic consensus that human brains developed through an evolutionary process like the rest of our anatomy, debates over which parts of our neurobiology and psychology are products of selection remain ongoing (Conroy-Beam et al., 2019; Keller, 2007; Penke & Jokela, 2016; Penke et al., 2007). Decades of research has produced a large, and often well-replicated, body of findings describing psychological features that seem universal and perhaps adaptive, collectively representing a vibrant enterprise in psychology (Conroy-Beam et al., 2019; Pinker, 2002; Walter et al., 2020).

Though more limited in quantity, some prior work has suggested that adaptations specifically designed to deal with various forms of victimization could exist in our species (Duntley & Shackelford, 2012; Wycoff et al., 2019). Duntley and Shackelford (2012) do not mention self-control specifically. Rather, they point out that our ancestors would have repeatedly encountered threats of violence and attempts at deception, and so adaptations for forming protective alliances represent one among several other adaptations for limiting harms from victimization (Duntley & Shackelford, 2012). The ideas of Duntley and Shackelford (2012) reflect a similar perspective in the field, which is that social interaction, social conflict, and intrasexual competition are among the important selection pressures that shaped our cognitive development (Cosmides, 1989; Mercier & Sperber, 2011; Pinker, 2002; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990; Walter et al., 2020; Wycoff et al., 2019). Favorable evidence has emerged on this front (Mercier & Sperber, 2011), along with some dissenting evidence specifically regarding the evolution of self-control (MacLean et al., 2014). While the specific selection pressures responsible may remain a source of debate, the broadly adaptive qualities of socially relevant cognitive traits including self-control seems quite defensible (Conroy-Beam et al., 2019).

In their primer on evolutionary genetics, Penke and colleagues (2007) provided a useful tutorial for thinking directly about the evolution of personality and cognitive traits like self-control. Virtually all complex traits are partly heritable, the result of numerous genetic variants exerting very small impacts overall (Chabris et al., 2015; Turkheimer, 2000; Willoughby et al., 2023). One might expect adaptations to lack heritable variation, assuming selection has winnowed it away across time (Boutwell & Maestripieri, 2023; Penke et al., 2007). Traits can be under heavy selection, though, and yet still be heritable. One way this can happen is when the number of genetic “targets” for selection is large, yet the effects of single mutations are small, thereby making it less likely that selection can eliminate all heritable variation (Penke et al., 2007).

Using a model described earlier by Cannon and Keller (2006), Penke et al. (2007, p. 559) describe the relevance to cognitive traits: “Just as many small creeks join to become a stream, and several streams join to become a river, many genetic and neurophysiological micro-processes (e.g., the regulation of neural migration, axonal myelinization, and neurotransmitter levels) might interact to become a specific personality trait.” Given its association with mating outcomes, extreme polygenicity, and ubiquitous heritability (among other specific qualities), they contend that general intelligence represents an adaptation impacted by mutation-selection balance, the process just described.

Self-control and closely related traits share some of these qualities. Across measurement strategies, decades of evidence reveals self-control to be a moderately heritable trait (Beaver et al., 2007; Bezdijan et al., 2011; Willems et al., 2019). The increased availability of imaging data has similarly revealed that the neural circuity implicated in the trait (and discussed below), involves both heritable and environmental contributions to variance (Achterberg et al., 2018a, 2018b; Jansen et al., 2015). Not unlike intelligence, self-control has been linked to other fitness-relevant outcomes like health and well-being (Moffitt et al., 2011). That said, whether self-control, or even the brain structure and function of its attendant neural circuitry, are appropriately understood as an adaptation subject to mutation-selection balance, remains an interesting but open question (Willems et al., 2019).

Other fields, specifically neuroscience and neurobiology, provide additional information about self-control that can be helpful when considering not only its evolutionary origins but also its more proximal effects now (Suddendorf et al., 2018). Compared with brain regions that were shaped earlier in our evolutionary past, the areas comprising the cortex and neocortex are among the areas added more recently (Lui et al., 2011; Suddendorf et al., 2018). The evolution of our neocortex has received considerable attention, as has a region known as the prefrontal cortex (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2006). The prefrontal cortex is of particular interest given the now clear evidence implicating function there as important for the exercise of selfcontrol. Because of its connections to evolutionarily older regions like the hippocampus (implicated in memory formation) and the amygdala (involved with processing threats), the prefrontal cortex is important for understanding the cognitive underpinnings of self-control and victimization.

Within the prefrontal cortex, particularly in the dorsolateral, orbitolateral, and medial cortices, much of the relevant circuitry underlying a family of constructs called executive functions is housed (Beaver et al., 2007; Diamond, 2013; Lui et al., 2011; Molnár et al., 2019; Preuss & Wise, 2022). Diamond (2013) proposed that the functions exist in three general types, inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, each encompassing several lower-level capabilities (Becharia et al., 1999; Diamond, 2013; Preuss & Wise, 2022). The sheer amount of scholarship on executive functions alone precludes short summarization (see De Ridder et al., 2012; Diamond, 2013; Preuss & Wise, 2022). However, the most relevant points connecting self-control and victimization can be presented with brevity. The first concerns the types of challenges that executive functioning helps to navigate. Diamond (2013, p. 136) proposed the following:

Executive functions (EFs; also called executive control or cognitive control) refer to a family of top-down mental processes needed when you have to concentrate and pay attention, when going on automatic or relying on instinct or intuition would be ill-advised, insufficient, or impossible. (Burgess & Simons, 2005; Espy, 2004; Miller & Cohen, 2001)

Among this family of traits resides self-control, which Diamond (2013, p. 138) aptly describes: “Self-control is the aspect of inhibitory control that involves control over one’s behavior and control over one’s emotions in the service of controlling one’s behavior. Self-control is about resisting temptations and not acting impulsively.”

The behavioral implications of low self-control are likely not difficult to anticipate. Negative consequences of impaired selfcontrol manifests in outcomes ranging from performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task to self-reported and officially recorded instances of fraudulent and violent behavior (Bechara et al., 1999; Boutwell et al., 2020). Because of its interplay with regions involved in threat and fear assessments (Marek et al., 2013), as well as those linked to memory formation (Preston and Eichenbach, 2013), it seems all the more possible that impaired executive functioning is relevant for victimization risk (see Bechara et al., 1999; Shin et al., 2006).

One of the ways to illuminate which tasks are linked to certain brain regions is to examine the consequences of damage or lesion in an area (Szczepanski & Knight, 2014). In their survey of the literature, Szczepanski and Knight (2014) described the consequences observed for lesions in different prefrontal regions, revealing that depending on the region, deficits emerged on measures assessing rule-learning and task switching, planning and problem solving, and novelty detection and attention, among others. The last area of impairment is interesting for victimization, because as Szczepanski and Knight (2014, p. 1008) observe: “The ability for humans or animals to detect, respond to, and remember novel stimuli in their environment is fundamental to survival and new learning.” Whether these findings can all withstand the scrutiny of replication remains to be seen. Impaired executive functions do not improve well-being, and frequently erode via effects on decision-making quality directly or some other more indirect pathway. As a result, executive functioning in general, and selfcontrol in particular, should be among the variables that increase risk of victimization.

Self-Control From the Confines of Criminology

We began in the literature outside of criminology for a specific reason, which was to offer a snapshot of many scientific disciplines that have made important contributions to the study of self-control across the decades (De Ridder et al., 2012). Criminologists have had an interest in self-control for decades as well. The difference, though, is that until recently criminology conducted its work in quarantine from the broader scientific community (Beaver et al., 2007; DeLisi et al., 2011). Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) proposed a general theory designed to explain all types of criminal behavior (violent and non-violent), as well as behaviors that were not criminalized, but capable of producing harm to the individual or others (e.g., smoking, alcohol abuse, etc.). They built it from the ground up starting with conceptualizing and operationalizing self-control, proposing, for example, that it captured preferences for simple versus complex tasks, a need for immediate gratification, among several other qualities (Beaver et al., 2007; DeLisi et al., 2011; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990).

The theory traced the development of self-control to a single critical period in early childhood. The causal force responsible for inculcating adequate self-control was a regimen of parental socialization tactics (Wright & Beaver, 2005). Parents needed to monitor the behaviors of children closely to correct impulsive and antisocial acts when they occurred (Boutwell & Beaver, 2010; Wright & Beaver, 2005). Beyond the ages of 8–10 years old, self-control became impervious to these socialization effects and remained relatively stable for the remainder of life. The theory was largely silent about any relevant neurological underpinnings, and it rejected outright the possibility of meaningful genetic influences on self-control (Barnes et al., 2013; Wright & Beaver, 2005).

The work attracted considerable attention over the years and in many key respects it has held up well to empirical scrutiny (Pratt & Cullen, 2000). Multiple meta-analyses have been conducted, and little doubt remains concerning the association between indicators of self-control and antisocial, aggressive, and criminal behavior (De Ridder et al., 2012; Pratt & Cullen, 2000; Vazsonyi et al., 2017). As the evidence mounted, there was interest in exploring the true “generality” of the theory by examining outcomes beyond overt behaviors. The concept of a “victim-offender overlap” predated the publication of the theory (Gottfredson, 1981, 1990; Singer, 1987; Wolfgang, 1958), and both then and now, robust evidence suggested that active offenders experienced a disproportionate risk of victimization (Broidy et al., 2006; Jennings et al., 2010). Scholars eventually recognized that factors exerting causal effects upstream of offending may be doing precisely the same thing upstream of victimization (Pratt et al., 2014; Schreck, 1999).

Given the nature of low self-control and how it shapes decision-making as a whole (see De Ridder et al., 2012; Moffitt et al., 2011), a consequence of impaired self-control might involve more frequent encounters with people—and situations—that increase the vulnerability of being defrauded, deceived, and physically harmed (Pratt et al., 2014; Schreck, 1999). Analyzing over 60 studies, Pratt et al. (2014) offered one of the more recent systematic reviews of evidence on victimization and self-control. Their analyses were multi-level and included just over 300 effect sizes. The results revealed that self-control consistently correlated with various types of victimization experiences. The effect sizes tended to be modest in size, however, highlighting the complex nature of victimization and its putative causes.

Since the publication of Pratt et al. (2014), evidence has continued to accumulate concerning the effects of self-control on victimization, including studies adopting more rigorous strategies for boosting causal inference capabilities (Boutwell & Maestripieri, 2023). In one of the more recent studies, Tanksley et al. (2020) examined a range of cognitive and personality traits to estimate their relationship to various forms of victimization. Many of the traits failed to withstand the stringent corrections for familial confounding—genetic and environmental—using a discordant twin design. However, self-control effects did emerge with some degree of consistency (Tanksley et al., 2020), a result in line with past work analyzing American sibling pairs (Boutwell et al., 2013).

Criminologists have made important contributions to the study of self-control, as evidenced by the work just mentioned. Though not its intention, this work has nonetheless helped to build a cognitive science understanding of victimization. The failure was in building the appropriate bridges to the relevant scientific fields, which is what Beaver et al. (2007, p. 1348) described years ago:

Both concepts—executive functions and self-control—call attention to the importance of regulating impulsive tendencies and the ability to control emotions and sustain attention. Both recognize the salience of mental capabilities and cognitive functioning to anticipate and forecast behavioral consequences. Both are concerned with the ability to modulate tempers and to inhibit inappropriate conduct. Most important, both recognize that problems with executive functions or problems with selfcontrol may lead to aberrant, delinquent, and violent behaviors. (Damasio, 1994; Goldberg, 2001; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Moffitt, 1990)

Cognitive Science and Victimization Moving Ahead

We have focused on self-control as a key executive function for a new theoretical science of victimization, but part of the maturity process for this work should include examination of other core skills in humans (Moffit, 1993; Moffitt et al., 2011; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011). Outside of executive functioning, variability in other domains such as verbal intelligence, abstract reasoning, and mathematical skills (i.e., indicators of general intelligence) are well-established correlates of educational attainment, occupational success, and overall life success with age (Koepp et al., 2023; Miller et al., 2011; Moffitt et al., 2011; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Penke et al., 2007). Indicators of self-control also correlate positively with indicators of intelligence (Meldrum et al., 2017), meaning that individuals who are good at regulating impulses tend to perform better on indicators of intelligence, which are also linked to life success (Koepp et al., 2023).

One of the studies best equipped to parse these effects was conducted by Moffitt and her colleagues using a sample of roughly 1,000 participants from the Dunedin cohort Moffitt et al. (2011). The design included a longitudinal “head-to-head” test, pitting self-control against indicators of intelligence. Self-control and intelligence were assessed early in life, and the analyses were intended to estimate which of the two exerted the larger and more consistent effect on various outcomes—including substance dependence, criminal behaviors, health, and economic success—across the life course. Self-control prevailed. Individuals with greater self-control reported better health, more formal education, and experienced more stable family lives. The effects seemed to replicate (though not all of the same variables were available) using an independent sample of European monozygotic and dizygotic twins. This is particularly interesting, given the capacity for well-designed twin studies to boost causal inference capacity in observational data (see Tanksley et al., 2020; Willoughby et al., 2023).

Very recently, Koepp et al. (2023) presented results from an attempt to replicate the original Moffitt et al. (2011) paper. Multiple longitudinal samples from both the United States (n = 1,168) and the United Kingdom (n = 16,506) yielded considerable support for the findings of the original study by Moffitt et al. (2011). Attention/self-control problems in childhood exerted consistent influence across the life course on outcomes considered hallmarks of prosocial functioning and healthy development. Dysregulation of attention early in life increased the risk of antisocial and criminal outcomes years later, while also eroding aspects of health and financial stability across time. The paper produced numerous interesting results, but the authors offered the following reflection as to how their study generally dovetailed with the original paper (Koepp et al., 2023, p. 1403):

Our analyses produced remarkably similar results; in some cases, coefficients were nearly identical to those reported by Moffitt et al. (2011). These convergent findings emerged from cohorts born in different decades than the Dunedin sample, from different countries, and assessed at two different stages of life—young adulthood in the U.S. cohort and middle age in the U.K. cohort.

Missing from both of these studies, of course, is the outcome of victimization examined with both intelligence and selfcontrol. There is, however, a nascent body of evidence concerning just intelligence and victimization (Beaver et al., 2016; Boutwell et al., 2017; Connolly et al., 2020; Tanksley et al., 2020). Using two different national samples of American respondents, Beaver et al. (2016) and Boutwell et al. (2017) both reported small to moderate effects of verbal intelligence on self-reported victimization. However, in a study mentioned previously, Tanksley et al. (2020) found that measures of intelligence could not withstand strenuous correction for familial confounding to the extent possible for self-control.

The Current Study

Despite the steady accumulation of work on this topic, some questions remain unanswered. Koepp and colleagues described one of the key blind spots nicely (2023, p. 1404):

Although there are cultural differences among the countries examined, each of them is high-income and Anglophone and the samples were mostly White. Though we did not find evidence for heterogeneity by family income or child gender, it is not yet clear how these findings would generalize to other settings. Unfortunately, there are few studies anywhere in the world that follow the same set of children prospectively into adulthood, so similar studies in other countries may not be forthcoming for a while.

Our intention is to begin filling this gap by analyzing the cognitive underpinnings of victimization with the type of data that Koepp et al. (2023) rightly characterize as being a frequently scare resource.

Methods

Data

The analysis for our study was conducted using data from the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). The FFCWS is comprised of approximately 4,700 families (Reichman et al., 2001), and was intended to be representative of a nationally based sample of non-marital births in large U.S. cities. The initial sample included approximately 3,600 unwed and 1,100 married couples (see Reichman et al., 2001 for additional study design details). To date, the FFCWS has followed the original sample of children and their families from birth up until the focal child has reached early teenage years (approximately age 15). Six waves of data have been collected so far, with Wave 1 beginning in 1998–2000, approximately 48 h after birth.

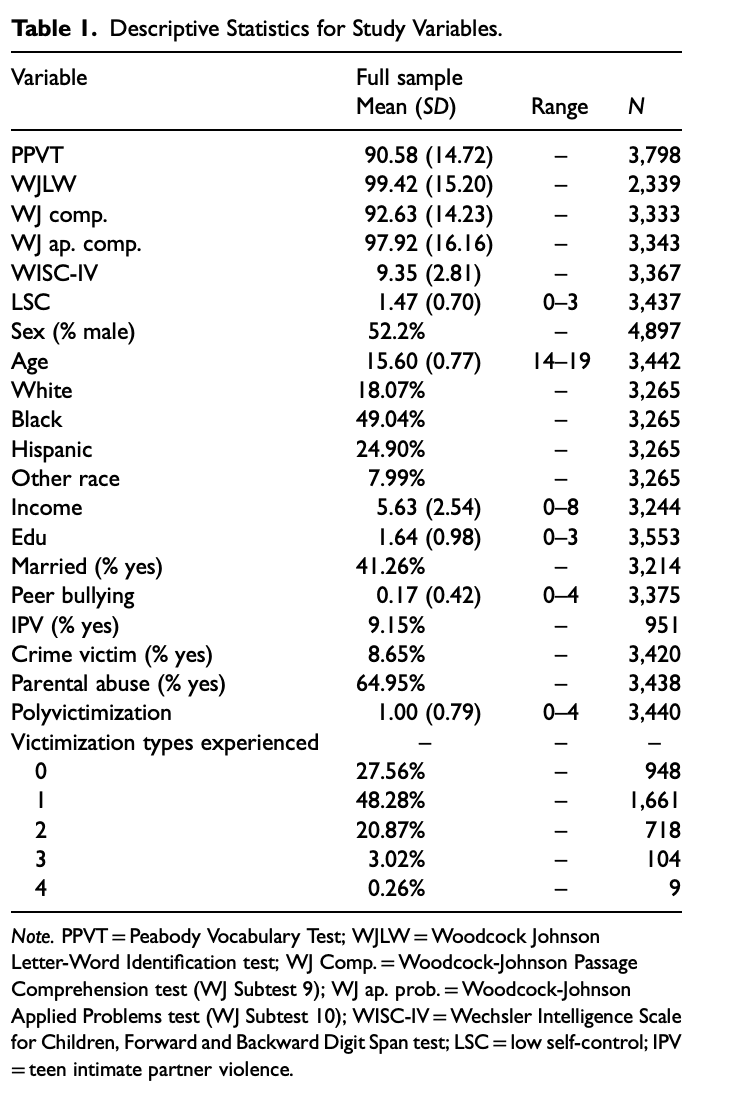

The remaining waves were collected via telephone-based core interviews with mothers and fathers when the children were ages 1 (1999–2001), 3 (2001–2003), 5 (2003–2006), 9 (2007–2010), and 15 (2014–2017). A subset of primary caregivers (typically the biological mother) also participated in a series of in-home interviews at Years 3, 5, and 9. Data from the adolescents directly were available in the form of self-reported interviews (N=3,444 of 4,663 eligible) at Wave 6 (Year 15) and were used for the analyses. The de-identified data from the FFCWS are publicly available and were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board for secondary analyses. All available observations were used in estimations, yielding sample sizes ranging from n=431–2,503 across models. Adolescents in the analytic sample were 48% female; 49% Black, 25% Hispanic, and ranged in age from 14–19 (Mage=15.6; see Table 1 for study descriptive statistics).

Measures

Adolescent Victimization. Peer Bullying. Adolescents self-reported on how often they were exposed to peer bullying in the past month with items adapted from the peer bullying assessment from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement (2010). Adolescents responded to four questions assessing how often kids at their school, “pick on you or say mean things to you,” “hit you or threaten to hurt you physically,” “take things, like your money or lunch, without asking,” and “purposely leave you out of activities.” Item response categories included: 0= never, 1=less than once a week, 2=once a week, 3= several times a week, 4= about every day. All four items assessing peer bullying were averaged into a mean score, where greater values represent greater exposure to peer bullying (α = .62).

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Adolescents who reported currently dating a romantic partner reported on whether their partners engaged in abusive behaviors (adolescents not currently dating a romantic partner were excluded on the measure). These items were adapted from the Toledo Adolescent Relationship Study (TARS; Giordano et al., 2001) and the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life Study (RDSL; Barber et al., 2008). Respondents were asked, “During this relationship, how often…, “has your partner put you down in front of other people,” “has your partner pushed you, hit you, or thrown something at you that could hurt?” These two items were coded as 0 = never, 1= sometimes or often and then summed and dichotomized to reflect the presence of adolescent partner abuse (1= yes, 0 = no exposure to IPV).

Crime Victim. Adolescents also reported on whether they have ever been a victim of a crime during their lifetime (0=no, 1=yes).

Parental Abuse. Adolescents self-reported on their exposure to parental psychological aggression and physical abuse in the past year with two items from the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998). Adolescents were asked if their primary caregiver “Shouted, yelled, screamed, swore or cursed at you?” and “hit or slapped you?” These two items were coded as 0=never, 1=sometimes or often and then summed and dichotomized to reflect the presence of parental psychological and/or physical abuse (1=yes, 0=no exposure to parental abuse).

Polyvictimization. In sum, a total of four types of victimization were assessed from the adolescent (Year 15) interview. To recap, these victimization items include exposure to peer bullying, adolescent IPV, being a victim of a crime, and psychological and/or physical abuse by their parent/primary caregiver. Dichotomous variables were created for each of the four victimization types and the polyvictimization score reflects a cumulative score of polyvictimization. In the study sample, polyvictimization scores ranged between 0 (no victimization) and 4 (exposed to all four types of victimization).

Childhood Intelligence. The Peabody Vocabulary Test (PPVT). This intelligence measure was assessed at ages 3, 5, and 9. The children’s scores were standardized by the FFCWS team based on the recommendations outlined in the PPVT Examiner’s Manual (Dunn & Dunn, 1997). Standardized scores represent children’s intelligence relative to their peers of the same age (Age 3 M =85.74, SD =16.66; Age 5 M =92.88, SD =16.09; Age 9 M =92.72, SD =14.95). The three PPVT scores were averaged into an index to represent an overall early childhood PPVT score (α=.75).

The Woodcock-Johnson Letter-Word Identification Test. Children were administered this measure of intelligence at the age of 5 (see generally, Woodcock et al., 2001). Scores were standardized to reflect children’s performance relative to their peers of the same age (M =99.42, SD =15.20).

The Woodcock-Johnson Passage Comprehension and Applied Problems (WJ) Test. These intelligence subtests were measured at age 9. The initial Passage Comprehension (WJ Subtest 9) items were designed to assess symbolic learning, or the ability to match pictures of words to pictures of the actual object (M = 92.63, SD = 14.23) (see generally, Woodcock et al., 2001). The second subscale was the Applied Problems (WJ Subtest 10), which assessed the child’s ability to analyze and solve mathematical problems (M = 97.92, SD = 16.16).

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) Forward and Backward Digit Span Test. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Digit Span subtest was also assessed at age 9 (Wechsler, 2003). The test was designed to measure the child’s auditory short-term memory, sequencing skills, attention, and concentration. Scores were standardized to reflect performance relative to same-age peers (M =9.35, SD =2.81).

Adolescent Low Self-Control. Dickman’s Impulsivity Scale. Adolescents’ impulsivity was assessed with six items from an abbreviated form of the Dickman’s impulsivity scale (Dickman, 1990). During Wave 6 adolescent interview, youth were instructed to think about how they have behaved or felt during the past 4 weeks for the following statements: “Often, I don’t spend enough time thinking over a situation before I act,” “I often say and do things without considering the consequences,” “Many times, the plans I make don’t work out because I haven’t gone over them carefully enough in advance,” “I often make up my mind without taking the time to consider the situation from all angles,” “I often say whatever comes into my head without thinking first,” and “I often get into trouble because I don’t think before I act.” The six items were recoded as 0=strongly disagree, 1=somewhat disagree, 2=somewhat agree, and 3=strongly agree and averaged to create an index of teen impulsivity (α=.79), where higher scores correspond to greater self-reported impulsivity.

Demographic Covariates. Adolescent sex, age, self-reported race/ethnicity, primary caregiver-reported annual household income (0=under $5,000 to 8=greater than $60,000), primary caregivers’ highest level of education (0=less than high school to 3=college or graduate), and primary caregivers’ current marital status (0=not married, 1=married to biological father or new partner) were all recorded at Wave 6 and included as covariates.

Plan of Analysis

The analyses were completed in a series of steps. First, regressionbased analyses were used to estimate the association between all five indicators of childhood intelligence and the four types of adolescent victimization at Year 15 (i.e., peer bullying, IPV, crime victim, and parental abuse), as well as the total polyvictimization score. The victimization outcomes were estimated with ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression, logistic regression, and Poisson regression (respectively). Next, adolescent low self-control was included in the models to examine whether the observed associations between childhood intelligence and adolescent victimization were attenuated once self-control was taken into account. All models include the covariates of adolescent age, sex, race, parental education, marital status, and household income (age, education, marital status, and income were reported at Year 15). Analyses were conducted in Stata/SE version 16.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the study population are presented in Tables 1. Approximately 52% identified as male and self-reported race/ethnicity as 81% non-White and 18% White. The age of the study population ranged from 14–19 (M=15.6, SD=0.77). Approximately 48% of the study population reported experiencing at least one type of victimization event, whereas 24% of the population reported experiencing two or more types of victimization.

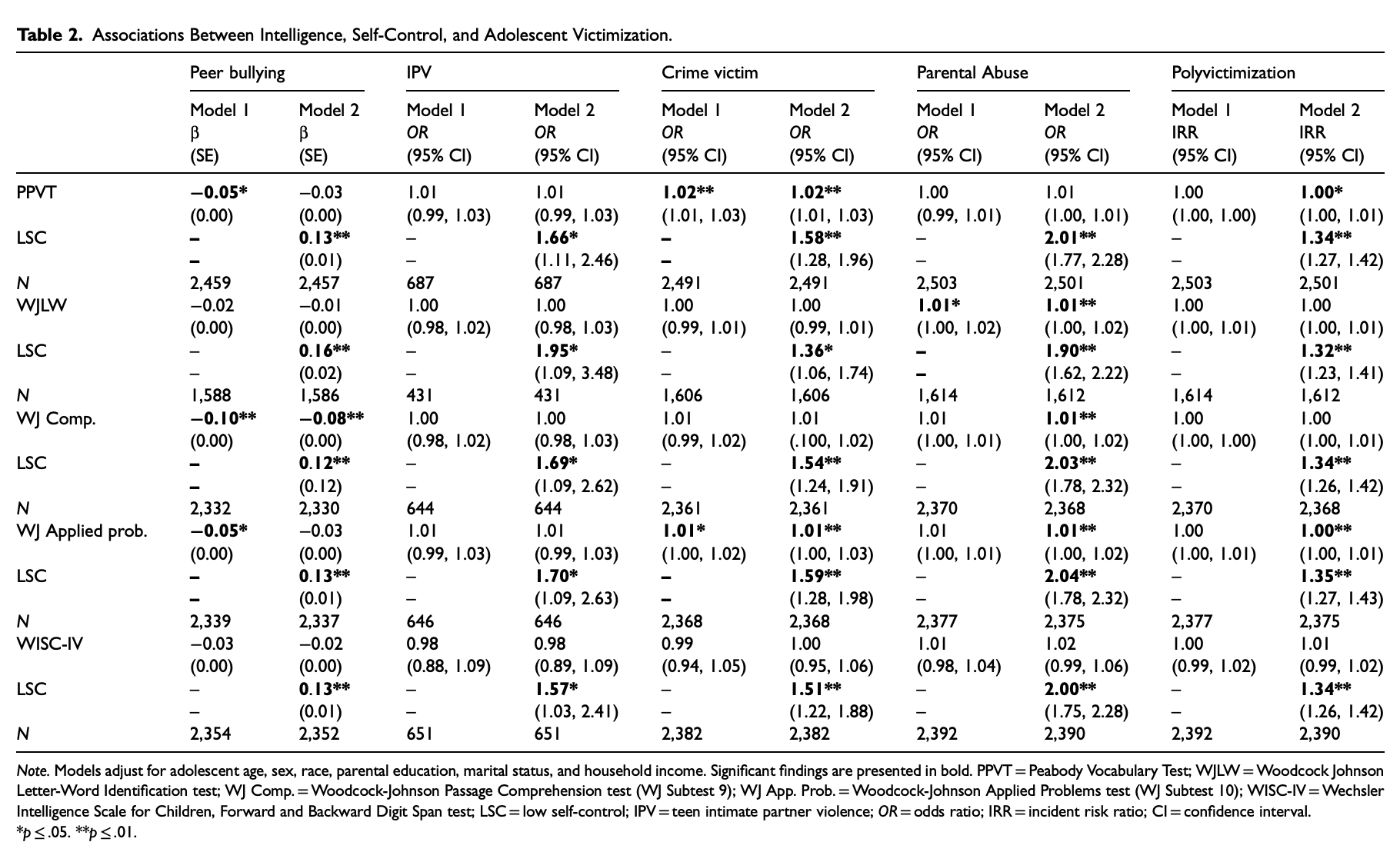

Next, the associations between the indicators of childhood intelligence and each adolescent victimization type are reported in each respective Model 1 of Table 2. For instance, peer bullying was significantly associated with the PPVT (β=−.05, p < .05), the WJ comprehension test (β = −.10, p < .01), and the WJ applied problems test (β = −.05, p < .05). Once low self-control was entered into Model 2, though, the only intelligence measure to remain significantly associated with peer bullying was the WJ comprehension test (β=−.08, p < .01). Certain intelligence measures were significantly associated with crime victimization, such that the PPVT (OR=1.02, p < .01) and the WJ applied problems test (OR=1.01, p < .05) were significant in Model 1. Moreover, both of these intelligence indicators remained significant once low self-control was included in Model 2. Finally, the WJLW test was also found to be weakly associated with parental abuse (OR=1.01, p < .05) and remained significant once low selfcontrol was entered into Model 2.

It is worth mentioning that some intelligence measures became significantly associated with adolescent victimization once low self-control was included in Model 2. For instance, the WJ comprehension test (OR=1.01, p < .01) and WJ applied problems test (OR=1.01, p < .01) each became significantly associated with parental abuse once low self-control was included in the model. Moreover, similar findings were reported for polyvictimization, where the PPVT became significantly associated with polyvictimization once low self-control was included in Model 2 (IRR =1.00, p < .05), as did the WJ applied problems test (IRR =1.00, p < .01).

Discussion

By drawing nearer to allied disciplines, part of our contention has been that the theories of criminologists with genuine explanatory reach will become more widely appreciated (Beaver et al., 2007; DeLisi et al., 2011; Laub, 2006; Moffitt, 1993). A similar intuition already exists in the field as demonstrated by the application of self-control theory to outcomes beyond just the commission of criminal behavior. Our goal was to describe how the theory already resides in the confines of cognitive science more proximally, and evolutionary science more generally—and how both areas provide invaluable insights that can further guide empirical scholarship. We also sought to add a layer of novel empirical evidence by utilizing a probability sample of at-risk and disadvantaged youth, which have frequently been neglected in behavioral science research. Further adding to the appeal of the Future of Families data, moreover, is its combination of size and methodological quality, particularly the inclusion of psychometrically robust constructs which are assessed longitudinally. Focusing on the various measures of victimization available in the data, we concentrated our efforts on calculating the effects of two psychological constructs which have long been central in psychology and criminology: measures of intellectual functioning and self-control.

Two themes emerged and both warrant some reflection prior to concluding. The first consistent thread to reveal itself involved repeatedly detecting effects of self-control on different forms of victimization, regardless of the type of victimization reported. In short, diminished self-control seems to be an “all-purpose” risk factor for victimization during adolescence. However, this is relatively unsurprising and generally aligns with prior work using both American and non-American respondents, as well as genetically sensitive and traditional observational data designs (Koepp et al., 2023; Tanksley et al., 2020). Somewhat more surprising was the second pattern which concerns the relative unimportance of intelligence measures on victimization experiences. When significant associations were detected, they were generally small in magnitude, effects which typically evaporated with the inclusion of self-control. One might have expected at least the possibility of this result, though, considering Moffitt et al. (2011) observed somewhat similar findings.

Limitations

The results should be interpreted within the context of their limitations, several of which should also create opportunities for future research. First, our measure of impulsivity was selfreported by teens at age 15 and was significantly related to teen victimization, yet we were unable to explore whether impulsivity assessed earlier in the life course operates in a similar fashion. Future work may wish to examine the relationship between childhood impulsivity and teenage victimization in high-risk samples of youth.

Second, although such analyses were outside the scope of the current study, future research may wish to further explore more nuanced questions, for example by testing whether adolescent self-control mediates the association between early childhood risk factors and teenage victimization in samples of similarly high-risk youth. Finally, it cannot be ignored that our paper adopts a largely standard analytical approach in behavioral science, one which is unable to fully correct for familial confounding, regardless of whether it stems from heritable or environmental factors (see Barnes et al., 2014; Tanksley et al., 2020; Willoughby et al., 2023). Such a limitation sets the stage nicely for replication attempts using behavior genetic tools and techniques moving forward.

Conclusion

Reflecting more generally, associations between self-control and behavioral outcomes are not particularly surprising at present, and the range of other outcomes and experiences it seems to also impact continues to widen (Koepp et al., 2023; Moffitt et al., 2011). Being victimized constitutes a particularly harmful type of experience, one in which the damage starts local and quickly becomes metastatic, impacting everything from reputation and financial security to psychological and physical well-being (Duntley & Shackelford, 2012). Criminologists recognized the broad social importance of the topic years ago, and while they recognized the reach of certain theories, they never fully appreciated why the reach existed in the first place (Schreck, 1999).

What makes a unified science of victimization appealing, particularly as it relates to the study of self-control, is that it puts a difficult topic in closer proximity to allied disciplines capable of offering valuable insights. Evolutionary theory provides the broadest context for thinking about the design of our psychological toolkits and it offers reason in advance to investigate associations between self-control and victimization (see also DeLisi et al., 2011; Duntley & Shackelford, 2012). Neuroscience and cognitive neuroscience continue to illuminate the circuity underpinning the emergence of selfcontrol and related traits (Beaver et al., 2007; Boutwell et al., 2022; Diamond, 2013). As clinical psychology and psychiatry continue to search for translational options for improving impulse regulation and self-control, these findings may also help to form strategies aimed at lowering victimization risk (Barkley, 2000; Boutwell et al., 2020). There is considerable work left to do but what seems clear is that a mature science of victimization cannot emerge unless fields prone to isolationism move beyond such stale traditions.