Introduction

Globally, the increasing aging population is widely documented with projections that the world’s population aged 60 years and older will rise from 900 million (12%) in 2015 to 2 billion (22%) by 2050 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018a). Of concern, is the prediction that elder mistreatment (or older adult mistreatment/abuse) will increase in line with population growth reaching 320 million victims worldwide by 2050 (WHO, 2018a, 2019). The World Health Organization defines elder mistreatment as:

[…] a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person. This type of violence constitutes a violation of human rights and includes physical, sexual, psychological, and emotional abuse; financial and material abuse; abandonment; neglect; and serious loss of dignity and respect. (WHO, 2018a)

Currently data indicates that one in six older adults (aged 60 years and older) experience mistreatment in community settings, although research suggests that only 1 in 24 cases is reported (WHO, 2018a). Prevalence rates of mistreatment among older adults are likely to be affected by under-reporting and barriers to help-seeking (e.g., fear of consequences for self or the perpetrator) (Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019).

Population aging presents a global challenge for countries (WHO, 2018b), including an inevitable surge in people diagnosed with dementia and additional demands placed upon health and social care services. Globally, around 55 million people have dementia, with over 60% living in low- and middle-income countries and this number is expected to rise to 78 million in 2030 and 139 million in 2050 (WHO, 2022).

Dementia, also more recently termed major neurocognitive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), is an umbrella term that describes the decline and loss of memory and other cognitive and behavioral abilities and functioning (Dementia UK, 2017). Common types include Alzheimer’s, Vascular, and Lewy Bodies. Dementia can have devastating consequences for individuals and their families including increased care needs and significant demands on caregivers (Pillemer et al., 2016).

Elder Mistreatment and Dementia

There is a growing body of literature that documents the associations between dementia and elder mistreatment (Fang & Yan, 2018; McCausland et al., 2016). Analyzing prevalence in this population is problematic since rates vary considerably, from 0.3% to 78.4% in the community and 8.3%–78.3% in institutional settings (Fang & Yan, 2018). Prevalence of elder mistreatment among individuals with dementia is, however, known to be significantly higher than for older adults without dementia (McCausland et al., 2016); although as noted earlier, prevalence estimates that rely on reported elder mistreatment are unreliable and mask the extent of the problem.

Research findings indicate a greater prevalence of psychological abuse and physical harm amongst individuals with dementia compared to other types of elder mistreatment (Cooper et al., 2009; Yan, 2014). Financial exploitation is a concern for older adults in the general population, with recent studies identifying a growth of this among people with dementia (Weissberger et al., 2019). Polyvictimization is recognized too, and is common among people with dementia (Dong et al., 2014; Wiglesworth et al., 2010).

Evidence suggests that there are multiple risk factors for all types of mistreatment among older adults including: Greater physical or cognitive impairment; chronic illness; frailty; impaired mobility; dependency; care needs; reduced capacity to undertake activities of daily living; and social isolation (Storey, 2020). Wiglesworth et al. (2010) argue that a dementia diagnosis in itself is a risk factor for elder abuse. Dependency can be a risk factor when the older adult is dependent on the abuser for financial, functional, emotional, or social support (Fang & Yan, 2018; Pillemer et al., 2016). These risk factors are associated with the individual being mistreated, but socio-ecological models have been used in several studies to examine and substantiate risk factors found at the level of the individual being abused and/or perpetrator, family, community and society (Pillemer et al., 2016; WHO, 2018b). Additionally, in scholarship highlighting relationship type as a risk factor, perpetrators are frequently family members such as an adult-children or spouse/intimate partners (Roberto, 2017).

Research examining the heterogeneity of care and safety needs is lacking; yet, for older adults these can serve to increase vulnerability to abuse (Lacher et al., 2016). This is especially the case for older people with dementia. Dementia is a progressive disease with each stage presenting different, more complex and extreme symptoms and behavior. This elevates people’s care needs, leading to heightened risk (Fang & Yan, 2018). Further, the demands of changing care needs where family members are the primary caregivers can be challenging to manage and can increase the likelihood of abusive behavior (Camden et al., 2011).

Understanding differences in mistreatment, care needs and risk factors between older adults with and without dementia is critical to an informed understanding of elder mistreatment which could enhance risk management strategies for preventing future abuse and neglect (Roberto, 2017). The current study uses a national UK dataset of reported cases of elder mistreatment to investigate those differences by comparing cases with older people reported to have dementia to those who do not. All reported cases are of alleged, not confirmed nor substantiated, mistreatment. Therefore, throughout the paper where we refer to cases of elder mistreatment, we acknowledge that all are alleged. We examine whether differences exist between elder mistreatment regarding: (1) the type of mistreatment experienced (applying the WHO definition), (2) care needs, and (3) risk factors.

Method

Study Design and Cases

Age UK is a charity working nationally and globally, to ensure that “every older person is respected, protected and treated with the dignity they deserve” (Age UK, 2018, online). Age UK operates a national information and advice line in the UK providing guidance on a range of issues including elder mistreatment. Every enquiry is logged by the advice line staff. This exploratory study examined 3 years (April 2014–March 2017) of anonymized reported incidents of alleged elder mistreatment logged by advice line staff. In total, there were 1408 reported incidents of alleged elder mistreatment, of which 299 included older people with dementia. Dementia was considered to be present where there was any evidence of dementia mentioned by the reporter either because it had been diagnosed or it was suspected (e.g., “The family believe … has been suffering with dementia for between 6 and 8 years”). A data management agreement was in place between Age UK and the researchers’ universities; ethical permission was also obtained from the latter.

Materials

Case logs were coded using a coding sheet to record evidence of mistreatment type (listed in Table 1), characteristics of the abused person, the presence or absence of care needs and risk factors (listed in Table 2). Each type of mistreatment, characteristic, and risk factor was coded as present or absent. The 10 risk factors examined were selected based on their support in Storey (2020) which reviewed 198 studies to identify empirically supported risk factors for perpetrators and victims of elder abuse. Operationalized risk factor descriptions were included in the coding sheet (see Table 2 for coded characteristics and examples of coding operationalization). For instance, the risk factor dependency on the perpetrator was considered present where there was evidence in the case log that the older person was socially, emotionally, financially, or functionally reliant on the perpetrator.

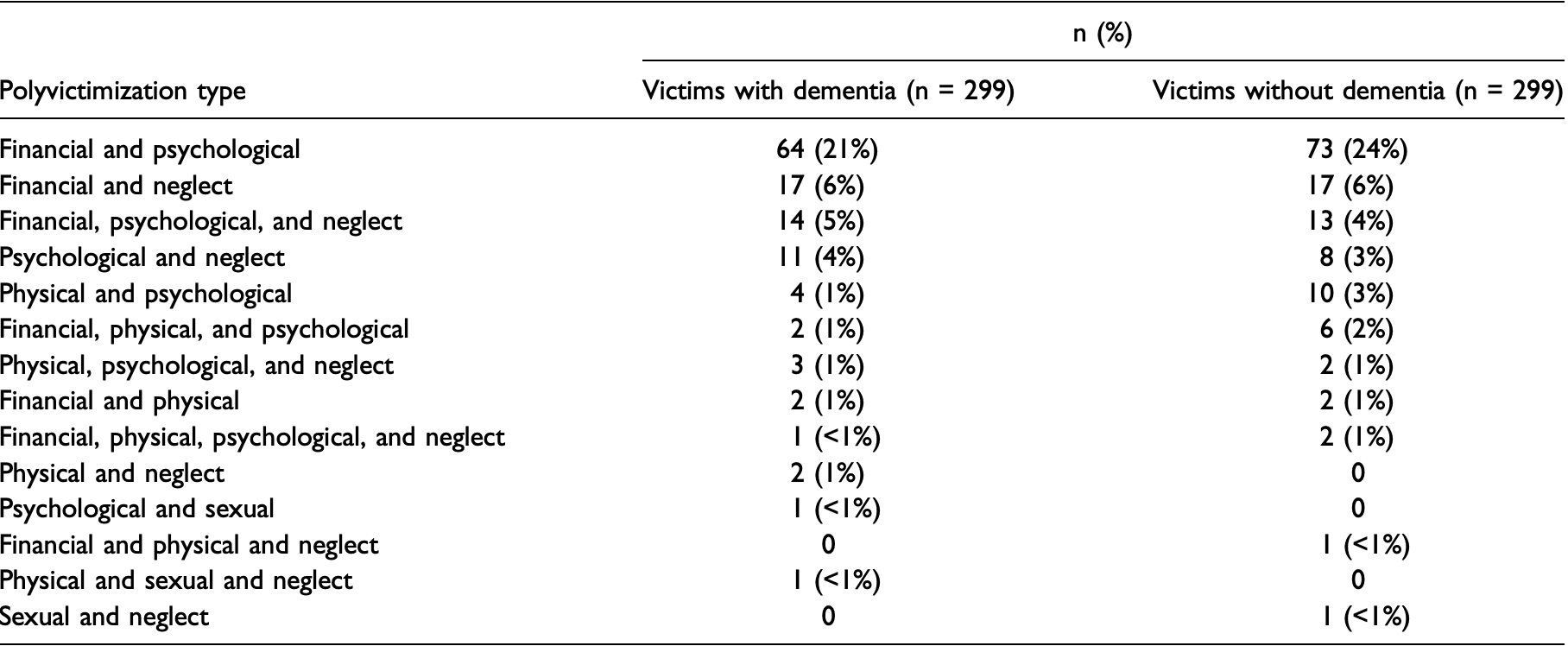

Table 1. Frequency of Polyvictimization amongst Older People with and without Dementia.

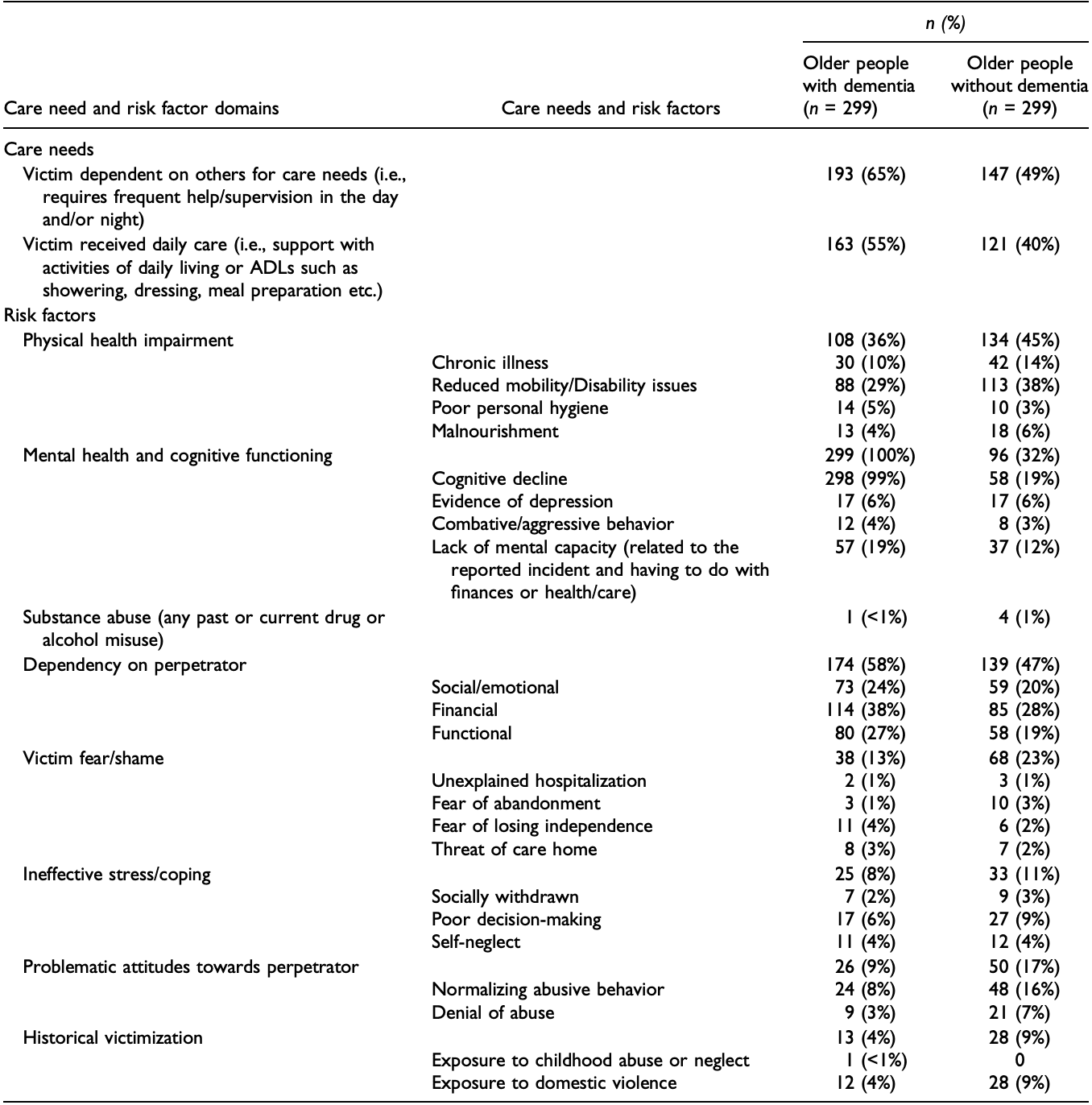

Table 2. Presence of Care Need and Risk Factors Displayed in Frequency and Percentage for Older People with and without Dementia.

Given the secondary nature of the data (from reported incidents to Age UK and not collected for research) some of the entries were brief in content and so did not expand beyond the indicative symptomology underpinning the dementia profile—but it was clear dementia was present/diagnosed. For the comparison cases of people without dementia, some may have been coded for cognitive decline based on an entry such as “…took M to the GP for a memory test and she has been diagnosed with short-term memory loss.” This could be the start of mild cognitive impairment or even dementia but the entries were brief and short-term memory loss could be as a result of many factors, for example, a UTI infection and therefore be temporary, but equally memory loss associated with age etc. If dementia was not stated or even suspected based on the case entry info, then they were coded as older adults without dementia.

Several steps were taken to ensure reliable coding. First, the third author, who developed the coding sheet, worked with a second rater, and discussed general coding guidance. Second, both raters coded five cases and compared them to identify any differences. As a result of this, changes were made to the coding sheet definitions to ensure variables would be coded to reflect the consensus. Third, a further 10 cases were coded and checked to ensure cases were now being reliably coded. Finally, a subsample of cases (n = 60, 10%) were coded by both raters, blind to each other’s ratings to calculate inter rater reliability. Four groupings of coded items were examined to assess reliability using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1), calculated using a two-way mixed effects (absolute agreement) model. All four groupings showed good to excellent agreement: mistreatment type ICC1 = .66, victim risk factors ICC1 = .74, perpetrator risk factors ICC1 = .75 and victim care needs ICC1 = .80 (Fleiss, 1986).

Data Analysis

The study employed a matched sample design wherein each case involving an older person with dementia was matched across specific criteria to a case with an older person without dementia. This design was chosen for two reasons. First, to correct for uneven sample sizes which could negatively impact analyses given that the number of people without dementia (n = 1109) was more than three times those with dementia (n = 299). Second, to control for potentially confounding variables across the two groups and ensure that differences identified were due to the presence or absence of dementia rather than the presence of these variables.

To create the matched samples a random number generator was used to identify cases within the non-dementia sample. Cases were then examined to see if they matched a case in the dementia sample, by assessing the four potentially confounding variables: (1) gender; (2) perpetrator relationship to the individual (i.e., spouse; family including adult-child, grandchild, sibling, or parent; relative including aunt, uncle, niece, nephew, cousin, and in-laws; friend/acquaintance; stranger; professional caregiver; legal professional); (3) relationship between the reporter of the alleged abuse and the person being mistreated (i.e., family, acquaintance, professional, or other); and (4) year of reported incident. Variables were identified and coded from the helpline call logs. A follow-up comparison found no significant differences on the four characteristics between people with (n = 299) and without (n = 299) dementia (p > .05), indicating the characteristics had been controlled for.

Frequency analyses were used to present descriptive case characteristics as well as the types of mistreatment present. Inferential statistics including Chi-square analyses and t-tests were used to make comparisons across the matched samples where data was dichotomous and continuous, respectively. Analyses were conducted in SPSS version 21.

Results

Case Characteristics

Alleged mistreatment was most often reported by a family member (n = 538, 90%), followed by an acquaintance or friend (n = 40, 7%), the person being mistreated (n = 8, 1%), a professional (n = 7, 1%), or another person (n = 5, 1%). Older people being mistreated were primarily female (n = 424, 71%). The mean age of individuals being mistreated was 85 years (SD = 7.46, range: 62–102); however, age was not recorded in most cases (n = 405, 68%). Perpetrators were more often male (n = 279, 47%; information was missing in n = 61 cases, 20%). Perpetrator age was missing too frequently to accurately report (n = 570, 95%). The relationship between the person being abused and perpetrator was most often parent and adult–child (n = 352, 59%), followed by spouse/partner (n = 72, 12%), other family (e.g., grandchild, sibling) (n = 87, 15%), friend/acquaintance/neighbor (n = 30, 5%), professional caregiver (n = 19, 3%), stranger (n = 15, 2.5%), other relationship (n = 13, 2%), and legal professional (n = 10, 2%).

Mistreatment Type

Polyvictimization (n = 257, 43%), which is the simultaneous presence of multiple mistreatment types, included two (n = 212, 82%), three (n = 42, 17%), or four (n = 3, 1%) types of mistreatment herein and was the most common type of alleged mistreatment. Table 1 presents the many different combinations of alleged mistreatment types reported. Financial exploitation (n = 255, 43%) was the next most common single type of alleged mistreatment followed by psychological abuse (n = 69, 12%), physical abuse (n = 10, 2%), sexual abuse (n = 3, 1%), and neglect (n = 4, 1%). Sample sizes were large enough for polyvictimization, financial exploitation, and psychological abuse to allow for comparisons between older people with and without dementia. Financial exploitation was significantly more common among adults with dementia (n = 140, 47%) compared to those without (n = 115, 39%), (X2 (1, N = 598) = 4.27, p = .04, φ = .09), whereas polyvictimization and psychological abuse did not vary significantly.

Care Needs and Risk Factors

The frequency of care needs and risk factors across the two samples are displayed in Table 2. In terms of care needs, older people with dementia were significantly more dependent on others for their care needs than those without dementia (X2 (1, N = 598) = 14.43, p < .001, φ = .16). Older adults with dementia were also significantly more likely to require daily care than those without (X2 (1, N = 598) = 11.83, p = .001, φ = .14).

With respect to victim risk factors, older adults without dementia (M = .61, SD .82) had more physical health risk factors than those with dementia (M = .49, SD = .74), t (596) = 1.99, p = .05, d = .15. Older people with dementia (M = 1.28, SD = .50) had more experiences of depression and cognitive functioning risk factors than those without dementia (M = .40, SD = .62), t (596) = 19.19, p < .000, d = 1.56. Given the confounding role that dementia would play in comparisons of mental health and cognitive functioning, each risk factor in this category was examined separately. Cognitive decline was significantly more common among people with dementia (X2 (1, N = 598) = 399.81, p < .001, φ = .82) as was a lack of mental capacity (X2 (1, N = 441) = 13.06, p < .001, φ = .17). The presence of depression and combative/aggressive behavior did not differ between people with and without dementia. Older adults with dementia (M = 1.47, SD = 1.38) were dependent on the perpetrator in more ways than those without dementia (M = 1.14, SD = 1.31), t (596) = 3.03, p = .003, d = .25. Older adults without dementia (M = .40, SD = .91) had more problematic attitudes toward the perpetrator than those with dementia (M = .20, SD = .66), t (596) = 3.08, p = .002, d = .25. Older people without dementia (M = .19, SD = .58) had experienced more types of historical victimization than those with dementia (M = .08, SD = .42), t (596) = 2.42, p = .016, d = .21. Risk factors that showed no difference between the samples were fear/shame and ineffective stress and coping. The presence of substance abuse in people who have been mistreated was too low to analyze statistically.

Discussion

The results of our exploratory study support previous research showing that older adults diagnosed with dementia are at an elevated risk of elder mistreatment (McCausland et al., 2016; Wiglesworth et al., 2010). Our results indicate that older adults with dementia are considerably overrepresented in our sample, at 22%, compared to the estimated 7% of older people with dementia in the UK population. Accounting for this overrepresentation is problematic without further information. Despite this, the finding that older adults with dementia were overrepresented in our sample and showed elevated rates of particular risk factors for mistreatment, may therefore indicate that older adults with dementia in our study have increased vulnerability and need targeted support.

Differences found across older people with and without dementia related to types of alleged mistreatment experienced, care needs, and risk factors. These differences suggest that older people with dementia were: more likely to experience financial exploitation; more dependent on others for their care needs; significantly more likely to require daily care; had more cognitive decline; and were more likely to lack capacity. In contrast, those without dementia had: more physical health risk factors; more problematic attitudes toward the perpetrator (specifically, normalizing or denying abuse); and experienced more types of historical victimization. It is not possible to make further claims about these findings without further contextual detail across both samples.

Our results were different from existing studies that indicate a greater prevalence of psychological abuse and physical harm amongst older adults with dementia compared to other types of elder mistreatment (Cooper et al., 2009; Yan, 2014). However, our finding that older adults with dementia were more likely to be victims of financial exploitation is consistent with recent research that shows a growth in financial exploitation for older people in general and, importantly, for those with dementia (Peisah et al., 2016). A recent study compared abuse across age groups revealing that some forms of mistreatment remained stable with age (e.g., controlling behavior) while financial exploitation is highest among women aged 65 and older (Stöckl & Penhale, 2015).

Our study found that polyvictimization was common for older people both with dementia and without dementia. This contrasts with other research which suggests that people with dementia experience higher rates of polyvictimization (Dong et al., 2014; Roberto, 2017). We examined a national, representative sample which was selected from sequential enquiries made over a three-year period. As a large proportion of the total sample alleged polyvictimization, it is salient that anyone screening for or taking reports of elder mistreatment habitually probes for polyvictimization to ensure meticulous, accurate identification, and reporting of abuse to facilitate appropriate supports. Another important finding is that neglect was found in combination with at least one other type of abuse in 9 of the 14 combinations we recorded (see Table 1). This also suggests future research on polyvictimization is needed.

The comparison of risk factors revealed important differences across both sub-groups. Older people without dementia had more physical health problems (chronic illness, impaired mobility, malnourishment) than individuals with dementia, yet, people with dementia had significantly more mental health conditions (depression) and cognitive problems (including and excluding dementia). Peisah et al. (2016) also found that a lack of capacity is an important risk factor in an analysis of elder abuse type and that the lack of financial competency amongst persons with cognitive impairment elevates the risk of financial exploitation through, for example, the misuse of power of attorney (a legal arrangement that allows someone to make decisions for another, or act on their behalf, if they are no longer able or wish to make their own decisions). Older adults without dementia had more problematic attitudes towards the perpetrator and prior victimization.

We found no significant differences across risk factors relating to ineffective or poor coping, experiences of fear or shame, or social care involvement, between people with and without dementia. We also found no difference in relation to the presence of combative/aggressive behavior which was surprising as this may co-occur with dementia. Numbers in this category were small so this needs to be explored in future research. Additionally, this lack of difference may reflect the true state of affairs or the limited information recorded in the case entries. Subsequently, it is clear that professionals involved in taking initial referrals or advice-giving should be trained and prompted to solicit and record more detailed information relating to empirically supported risk and need factors (see Implications for health and social care professionals below).

In relation to levels of dependency in older people with dementia, the results indicated a greater need for assistance or oversight of financial management, social interactions, and functional tasks such as daily care or transportation. Dependency in relation to these functional tasks is an important risk factor for abuse among persons with dementia. Additionally, dependency impedes help-seeking as older people may fear the loss of care and family/social contact. People with dementia were also significantly more dependent on others for their needs and this included the requirement for daily care. This suggests that the potential for financial exploitation is greater due to increased contact with carers and more frequent opportunities (also found by Lacher et al., 2016).

Despite limited perpetrator information, there was a clear indication that the majority of victims were female (71%) and perpetrators were mostly male adult children (59%) suggesting that elder mistreatment is gendered. This reflects existing studies (Roberto, 2017; Rogers & Storey, 2019). This is an important point as whilst a feminist lens is often used to examine violence against women and girls, a gender-based analysis of elder mistreatment is often lacking (Weeks et al., 2018). There are, however, studies that show more male victimhood and that males report abuse less. Therefore, there is a need for rigorous future research examining elder mistreatment using a gender-based analysis to advance understanding as to whether elder mistreatment is gendered across different subtypes of elder mistreatment and across specific contexts.

Implications for Health and Social Care Professionals

The results have implications for the health and social care professionals providing care to older adults living with dementia in terms of the identification, assessment, and management of mistreatment. As individuals with dementia had more mental health and cognitive health risk factors (and abuse can cause/exacerbate mental and physical ill health), there can be a greater need for health and social care, particularly when there is an inevitable progression of dementia. Given the health needs of people with dementia and likelihood of regular contact with health professionals, Lazenbatt et al. (2013) argue that healthcare practitioners, in particular, are in a unique position to identify mistreatment and signpost victims and families to support. As such, health professionals working in the field of dementia care should be trained in the use of screening tools to enable them to recognize the signs and symptoms of various forms of elder mistreatment. Available screening tools (such as those developed by the National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly, https://www.nicenet.ca/tools) can be adopted into such training.

Improved awareness and recognition of elder mistreatment among health and social care professionals should lead to increased identification and reporting of abuse with timely and appropriate intervention, such as safety planning or advocacy. A recognition of the dynamic nature of risk relative to the progressive nature of dementia should be reflected in assessments and interventions. For example, planned case reviews should reassess risk and need accounting for the progressive nature of dementia, the deterioration of health and wellbeing and the increased likelihood of formal and/or informal caregiver involvement, along with increased vulnerability and risk of mistreatment. If relevant in the case of health or social care professionals without a safeguarding remit, a referral should be made to a safeguarding professional who can implement appropriate management strategies.

Awareness training for all health and social care professionals should draw attention to research, such as the current study, which indicates that adult-children are the primary perpetrators of mistreatment, and that when abuse is perpetrated by adult-children, parents are highly reluctant to report abuse for a number of reasons such as love, shame, or embarrassment (Roberto, 2017). This will enable professionals to embed evidence-informed practice in assessment, professional judgment, decision-making, and interventions.

To safeguard people at the point of a dementia diagnosis, ideally, two processes should take place. First, is the assessment of risk factors for elder mistreatment possessed by older adults with dementia by the health or social care professional with some consideration of the potential presence or risk of abuse. Safeguarding conversations should involve the older adult to support autonomous choice as much as possible and to improve quality of life, wellbeing, and safety. Positioning people as experts in their own lives and working in partnership enables them to reach better resolution or management of their circumstances (Crockett et al., 2018); for example, by including them in decision-making and safety planning.

Second, in cases of identified abuse, an intervention strategy should consider levels of dependency on the perpetrator and seek to source replacement support where appropriate. At the point of reporting, older people should be made aware that their best interests and safety will be prioritized and this may mean sourcing alternative support where the perpetrator is the primary caregiver. Implementing prevention or early help measures, supporting those with caring responsibilities to develop effective coping strategies to reduce and relieve caregiver burden and anxiety could improve outcomes or avoid mistreatment altogether (Pillemer et al., 2016).

Our results show intervention may be needed for both older adults with and without dementia in relation to the need of daily care. When considering the role and contribution of informal (unpaid) caregiving, a critical stance is needed towards some of the more contested, hackneyed theories, such as caregiver stress, particularly as research on caregiver stress reports divergent findings. A study conducted by Özcan et al. (2017) found that abuse in situations of informal caregiving was often bidirectional in that those caregivers who were being mistreated were more likely to also perpetrate abuse. Additional types of intervention could support individuals who are reluctant to cut ties with their caregiver despite this person being the source of mistreatment. Processes of normalizing or denying mistreatment, in this case, may result as people may be less likely to separate from the perpetrator, seek help, or accept assistance. Research to improve understanding of these complex barriers to help is needed as it could inform targeted and more effective interventions.

Finally, in case management for those people with dementia, intervention might include the removal of the individual from the abusive setting, while it can cause distress and confusion, safeguarding them might be the priority to ensure their safety and wellbeing. If no significant and immediate risks are identified, to encourage continued help-seeking, a safety plan might identify community-based support and resources that are available to meet the person’s needs, such as specialist older persons or domestic violence services. Further, a victim-centered, rights-based approach to case management, where the older adult is included as much as possible in the decisions made in their case, could help to alleviate that distress and confusion (Crockett et al., 2018).

Limitations

One limitation of our study is the issue of ambiguous, missing, or incomplete data in secondary data. Call-takers did not routinely record victim age but when they did ask, people were within the appropriate age range. Where callers described the older adult as having dementia, this does not necessarily mean that the person did actually have dementia. It is not known if call-takers recorded a dementia diagnosis for the person of concern, and then, in some cases, asked no further question regarding health needs and, as a result, additional data on co-occurring physical and mental health needs went unrecorded. All the cases included in the sample were recorded by call-takers as cases of alleged elder mistreatment. It is possible that false positives and negatives occur, and in the case of the latter there may be important differences in cases of mistreatment that go unreported.

Individuals with mid to advanced dementia would be less capable to reporting mistreatment than those without dementia and if they did, may be less able to provide information on the risk factors collected. It is important to note, however, that adults in the early stages are still able to report. This could mean that both mistreatment and risk factors among people with dementia were underreported here. However, this under-reporting may be somewhat mitigated by the fact that one UK study found that 88% of mistreatment reports to a helpline are made by someone other than the victim (Fraga Dominguez et al., 2022).

Our study was unable to undertake an in-depth analysis of carer or perpetrator traits and behavior. Our focus on victims of elder mistreatment, rather than perpetrators, reflects the sample provided by Age UK as there was little information provided about perpetrators in the case entries given the focus on supporting the mistreated older person and/or reporter. Ostensibly, the focus on victims would seem appropriate given the charity’s aim to provide support to older adults experiencing mistreatment. However, recent research shows that implementing risk management strategies focused on the perpetrator such as physical treatment, social support, and communication most commonly resulted in positive case outcomes (Storey et al., 2021). This suggests that collecting and suggesting support/interventions for perpetrators could be a beneficial addition to the charity’s current practice.

Finally, some of the subsamples (reported in Table 2) were small and we were unable to make comparisons and therefore only did make comparison where statistically appropriate. We therefore adopted caution in making conclusions.

Conclusion

Elder mistreatment is a global public health concern and existing empirical evidence demonstrates heightened risk of mistreatment for older adults with a dementia diagnosis (McCausland, et al., 2016;Wiglesworth et al., 2010). This is concerning in light of increasing rates of dementia. In particular, it is clear that when experiencing abuse, older people with dementia are particularly vulnerable to financial exploitation and polyvictimization. The latter warrants further rigorous investigation to advance understanding about polyvictimization for older adults with dementia, or a comparison of those with and without dementia. Future scholarship should also examine mistreatment amongst adults under age 65 with early onset dementia as this population is currently neglected in research.

The results of our study suggested two victim profiles. Older people with dementia suffered from more mental health and cognitive problems and had higher care needs while those without dementia presented with specific risks and needs related to physical health, attitudes, and prior victimization. This greater understanding of the specific elder abuse risk factors for older adults with and without dementia, could contribute to identifying victims and those at risk, including at specific stages of contact with the medical system, as well as reducing risk through the mitigation of risk factors (Peisah et al., 2016; Storey, 2020). The results suggest specific educational pathways for health and social care professionals caring for older adults suffering from dementia as well as specific intervention targets for safeguarding professionals dealing with older people without dementia.

The dearth of existing research draws attention to the knowledge gaps within elder mistreatment case management. The direction of future research needs to enhance understanding about the types of abuse amongst older adults with dementia to inform case management amongst health and social care professionals whose remit may include the detection and prevention of abuse or risk. This would benefit from evaluation to understand the efficacy of education for professionals. In addition, research exploring perpetrator data to analyze risk factors would also enhance case management. Finally, enhancing knowledge of mistreatment types across multi-agency networks of professions who support older people with dementia is key to an effective case management in the future.